Abstract

Electrochemotherapy is gaining recognition as an effective local therapy that uses systemically or intratumorally injected bleomycin or cisplatin with electroporation as a delivery system that brings drugs into the cells to exert their cytotoxic effects. Preclinical work is still ongoing, testing new drugs, seeking the best treatment combination with other treatment modalities, and exploring new sets of pulses for effective tissue electroporation. The applications of electrochemotherapy are being fully exploited in veterinary oncology, where electrochemotherapy, because of its simple execution, has a relatively good cost–benefit ratio and is used in the treatment of cutaneous tumors. In human oncology, electrochemotherapy is fully recognized as a local therapy for cutaneous tumors and metastases. Its effectiveness is being explored in combination with immunomodulatory drugs. However, the development of electrochemotherapy is directed into the treatment of deep-seated tumors with a percutaneous approach. Because of the vast number of reports, this review discusses the articles published in the past 5 years.

Keywords: electrochemotherapy, preclinical studies, veterinary oncology, human oncology

Introduction

The term electrochemotherapy was coined in 1991 by Lluis Mir in a study describing the effect of local application of noncytotoxic electric pulses on subcutaneous tumors after intramuscular injection of bleomycin.1 This treatment, which was named electrochemotherapy, led to a reduction in size and even the eradication of induced tumors in immunocompetent and nude mice. This work stimulated other groups, namely, Heller in the United States and Miklavcic and Sersa in Slovenia, to participate in experimental nonclinical work.2,3

For good antitumor response of electrochemotherapy, two prerequisites must be fulfilled: first, the electrical parameters of applied electric pulses should be selected in such way that they will cause reversible electroporation of cell membranes, preferably in all cells in tumors. Second, the drugs used in combination with electroporation should have limited or no transport available across the plasma membrane and should be highly cytotoxic once inside the cells. Bleomycin, as a hydrophilic antibiotic with endonuclease activity was a perfect candidate.4 However, also cisplatin, which was the second drug that was introduced into electrochemotherapy,5 have properties that makes it suitable drug for combination with electroporation. Cisplatin can enter the cells through copper transporters, but in limited quantities, therefore electroporation greatly enhances the uptake and consequently cytotoxicity, as the primary target of cisplatin in cells is DNA molecule. Cisplatin forms DNA adducts that lead to cell death, primarily apoptosis.6

Because of the remarkable antitumor effectiveness of this treatment in preclinical studies, very soon clinical trials were started in different types of tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.7–9 Extensive work, which was also performed in the frame of two European Union funded projects, Cliniporator and European Standard Operating Procedures of Electrochemotherapy, resulted in the publication of results of clinical trials and the Standard Operating Procedure for Electrochemotherapy.10,11 This publication, together with the commercially availability of electroporators certified for clinical use, represented a milestone in the development of electrochemotherapy, because thereafter each year more clinical centers in Europe started to use electrochemotherapy. In addition, the number of publications describing the results of clinical studies has steadily increased.

Another milestone in electrochemotherapy was its inclusion in national and European Union guidelines for the treatment of melanoma metastases, skin tumors, Kaposi's sarcoma, and liver metastases of colorectal cancer. The increasing amounts of results in the field of electrochemotherapy, preclinical and clinical, also made it necessary to standardize the reporting of the methods and results; thus, two articles dealing with recommendations on the preclinical as well as clinical use of electroporation in electrochemotherapy were published. The aim of these two publications was to provide guidelines for authors as to what should be included in the publications, which should ensure the reproducibility of the protocols and provide the data for a comprehensive meta-analysis of clinical data.12,13

Recently, a handbook of electroporation and several comprehensive review articles were published on electrochemotherapy14–16; thus, the aim of this review was to discuss the recent literature, published in the past 5 years, on electrochemotherapy in the three main areas where electrochemotherapy is studied and applied: in preclinical in vitro and in vivo studies in laboratory animals, in veterinary oncology, and in human clinical oncology. All studies on electrochemotherapy in the past 5 years are included into this review and grouped according to the specific topics or areas of research.

Preclinical Studies

Preclinical studies on electrochemotherapy can be divided into three main research areas. The first area is the use of the standard chemotherapeutics bleomycin and cisplatin in new entities of cancer, not tested before in electrochemotherapy, and in new combinations with other therapeutic modalities. The second area is evaluating new antitumor compounds in combination with electric pulses that are used for electrochemotherapy. The third area is the evaluation of new electrical features (i.e., different types of pulses) and the mathematical/numerical modeling of different effects pertinent to electrochemotherapy.

Electrochemotherapy: new tumor entities and new combinations

In the first area, electrochemotherapy was combined with another innovative technique, cold plasma, in a mouse melanoma model. The combined treatment resulted in a higher number of cured mice than electrochemotherapy alone. Plasma therapy alone was less effective than electrochemotherapy with bleomycin; nevertheless, the authors propose that such treatment can be used as an adjunct to electrochemotherapy or even as a potential alternative in palliative intent because it can be applied without anesthesia.17

In principle, owing to the physical properties of electroporation, electrochemotherapy with either cisplatin or bleomycin should work on any type of tumor; however, increasing evidence indicates that tumors respond with different response rates to electrochemotherapy. This was demonstrated in preclinical, and in veterinary and human clinical trials. The reasons for difference in response are multifaceted and include physical features pertinent to electrochemotherapy, such as unavailability of the drug and insufficient coverage with electric field and biological, pertinent to patient, such as previous treatments, difference in tumor microenvironment, mutational status, and so on.2,14,18

Thus, electrochemotherapy is still evaluated in different types of cancer, either in vitro or in vivo, including colon carcinoma CT26 (in vitro)19; bladder cancer SW780 (in vitro and in vivo)20; fibroblasts, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC; in vitro) and two squamous cell carcinomas, CAL-27 and SCC-4 (in vitro)21; ovarian cell lines OvBH-1 and SKOV-3 (in vitro)22; human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (in vitro)23; BRAF-mutated melanoma cells (SK-MEL-28) and their counterpart without mutation, CHL-1 cells (in vitro)24; chemoresistant uveal melanoma cells (Mel 270, 92-1, OMM-1, OMM-2) (in vitro)25; primary cells from metastatic pancreatic tumors (in vitro)26; human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma 2A3 (in vitro and in vivo)27; Lewis lung carcinoma and CT 25 colorectal carcinoma (in vivo)28; conjunctival melanoma CRMM1 and CRMM2 and normal conjunctival epithelial cells HCjE-Gi (in vitro)29; radioresistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma FaDuRR (in vitro and in vivo)30; and small cell lung cancer H69AR cells (in vitro).31

In general, it was demonstrated that electrochemotherapy with bleomycin or cisplatin causes immunogenic cell death in colon carcinoma19,28; that human endothelial cells are more susceptible to electrochemotherapy than tumor cells,21 supporting the antivascular effect in vivo; that electrochemotherapy is effective in ovarian carcinoma cells resistant to standard therapy22; and that electrochemotherapy is also effective in neuroblastoma and primary pancreatic tumor cells, which was not demonstrated before.23,26 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that electrochemotherapy with cisplatin is a promising therapeutic approach for bladder cancer20 and that it is more effective in HPV-positive than HPV-negative head and neck tumors.27 For electrochemotherapy with bleomycin, it was demonstrated that it is more effective in melanoma cells that harbor BRAF mutation24 and in melanoma cells that are chemoresistant.25 In addition, electrochemotherapy with bleomycin is more effective in radioresistant head and neck tumors than electrochemotherapy with cisplatin,30 and it is also effective against small cell lung cancer cells.31

Recently, it was shown that pancreatic tumor cells died from necroptosis rather than from necrosis or apoptosis after electrochemotherapy with bleomycin, cisplatin, and oxaliplatin.32 In addition, changes in the expression of stemness markers (Nanog and Oct3/4) in pancreatic tumor cells that survived electrochemotherapy were demonstrated. This change in expression could potentially contribute to the initiation and/or recurrence of pancreatic cancer after treatment and can represent a new target for the development of new therapeutic options.33

Many cancer studies are currently exploring immunomodulatory therapies in combination with standard cancer treatments, but only two studies were on the preclinical level exploring this combination. A synergistic effect was shown for the combination of electrochemotherapy with cisplatin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which has direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells and antiangiogenic effects, in a murine sarcoma tumor model.34 Another immunomodulatory agent combined with electrochemotherapy with cisplatin was an anti-inducible T cell costimulatory (iCOS) agonist antibody. The restriction of iCOS expression to T cells, which have already recognized tumor antigen, results in the expansion and activation of a range of antitumor T cell clones and thus pronounced antitumor activity. The combination was tested on CT-26 tumors and resulted in a 50% tumor cure rate with 100% resistance to tumor rechallenge.35

New candidate compounds for electrochemotherapy

The second area of preclinical research was elaborating on combining electroporation with new candidate compounds to achieve high and selective cytotoxicity toward tumor cells. Among many compounds tested, that is, doxorubicin,36 ruthenium (III) compound,37 5-fluorouracil,38 phthalocyanines,39 photofrin,40 curcumin,41 the trans-platinum analogue trans-[PtCl2(3-hmpy)2],42 oxaliplatin,43 betulinic acid,44,45 oat β-glucan,46 cyanine IR-775,47 catechin,48 and sodium decahydrodecaborate,49 only calcium electroporation was extensively studied.50–58 Calcium electroporation effectively causes tumor necrosis, leaving the normal tissue less affected, making it a very promising compound for further clinical evaluation as it does not belong to the antineoplastic drugs, thus precautions related to antineoplastic drugs regarding storage, handling, disposal, and toxicity and mutagenicity are not an issue for calcium electroporation.

Electrochemotherapy: new electrodes and numerical modeling

The third large area of preclinical research is dealing with different types of electrodes that can be used in vitro, in vivo, or in humans, that is, grid, single needle, or endoscopic,59–64 with different types (e.g., sine wave pulses, pulsed electromagnetic field, and high-frequency short bipolar pulses), and parameters of electric pulses (amplitude and frequency).65–69 The overall aim of these studies is to provide new electrodes that will be able to reach/treat the tumors that are not accessible with the current electrodes that are on the market and to provide electrodes that will not induce pain, muscle contraction, and/or skin burns, that is, undesired side effects that are commonly reported in clinical studies on electrochemotherapy. Another approach to foster and push forward electrochemotherapy is advanced numerical modeling of treatment, either in vitro or in vivo, to elucidate parameters that can influence the treatment outcome or to provide feasibility studies for future perspective electrochemotherapy treatment of tumors.70–78

New developments

In addition to the abovementioned areas of research, the Miklavcic group showed that magnetic resonance electric impedance tomography can be used for determining the electric field distribution during electrochemotherapy, which has important implications. Namely, this could enable corrective intervention during the procedure to ensure better electric field coverage of tumors and consequently better treatment outcome.79 Furthermore, Golzio and colleagues developed a fluorescence imaging technique for the electrochemotherapy treatment of micrometastases in the peritoneal cavity during open surgery, which could represent an important tool for the treatment of inoperable metastases.80 Our group developed a new, highly sensitive method for the identification and quantification of bleomycin in tumors and serum. This method, liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry, enables the determination of bleomycin pharmacology in different groups of patients, which will in turn lead to adjustment (personalization) of the drug dose applied to a specific patient, that is, elderly individuals, young individuals, and individuals with impaired kidney function, and so on.81

Studies in Veterinary Oncology

Electrochemotherapy is gaining much attention in the veterinary field. The main reason for this is that electrochemotherapy is a very effective treatment, for example, in mast cell tumors in dogs, which are the most common skin tumors in dogs. The complete response rate of mast cell tumors after electrochemotherapy (70%) is comparable with or even higher than that of surgery (50%).82 Furthermore, in many cases, electrochemotherapy is less invasive than surgery, causes fewer side effects than radiotherapy, and can be repeated if needed, without the development of chemoresistance. It is easy to perform and is relatively inexpensive, especially in comparison with radiotherapy.83 The popularity of electrochemotherapy among veterinarians is also demonstrated by high attendance at the “Veterinary workshop on electroporation-based treatments.”84 In 2018, 21 participants from Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Romania, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom attended the workshop, which also includes practical work on the electrochemotherapy treatment of dogs, cats, and exotic pets.

Electrochemotherapy is also being used in the treatment of exotic pets, such as ferrets, cockatiels, turtles, rats, and hedgehogs.85–91 Especially in turtles, where fibropapillomatosis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality of sea turtles, electrochemotherapy is a very promising treatment option. Complete responses were obtained after electrochemotherapy with intralesional bleomycin in two treated turtles presenting fibropapillomatosis and one with squamous cell carcinoma, with no healing complications and no recurrence up to 1 year.85,91 In cats, because of the severe toxicity of cisplatin, electrochemotherapy with bleomycin is being used, mainly for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head.92,93 Electrochemotherapy was well tolerated, with no evident local or systemic side effects. In both studies, the complete response rate was ∼80%. Therefore, electrochemotherapy should be considered as an alternative treatment option to other ablative locoregional therapies, especially in cases where tumors are located in sensitive regions of the body and other therapies are not accepted by owners because of their invasiveness, mutilation, or high cost.92,93

The main role of electrochemotherapy in veterinary oncology is in the treatment of various tumors in dogs. The owners of dogs are increasingly prone to treat their pets, and electrochemotherapy is a viable option for these cases, especially skin tumors. Electrochemotherapy is becoming a standard therapy for mast cell tumors and an adjuvant treatment to surgery for soft tissue sarcomas. The results of electrochemotherapy treatment of two large cohorts of dogs with soft tissue sarcoma were recently published. In a study by Torrigiani et al.,94 52 dogs with 54 soft tissue sarcomas were treated either with electrochemotherapy with bleomycin alone, during open surgery, or with electrochemotherapy as an adjuvant to surgery. The recurrence rate in groups that were treated with electrochemotherapy during or after surgery was similar (23% and 25%).94 In another study, in addition to an intravenous administration of bleomycin, the tumor bed was also infiltrated with cisplatin. This combination was very effective, 26 of 30 dogs were without evidence of recurrence, and the median estimated disease-free interval was 857 days.95 As mentioned, electrochemotherapy can be used as a treatment of choice for smaller mast cell tumors (median 1 cm), or in cases of larger tumors, it can be combined with surgery, especially in locations (extremities and the head) where surgery with curative intent would involve functional mutilation.96

In mast cell tumors, electrochemotherapy was also combined with immune gene therapy with interleukin-12. The main aim of the study was, in addition to treatment response, the evaluation of the safety of the gene therapy, thus horizontal gene transfer to bacteria isolated from the dogs' skin and the presence of plasmid on the site of injection. After 1 week, the plasmid was not detected at the site of injection, and no horizontal gene transfer was obtained. The efficacy of the therapy was pronounced: 13 of 18 (72% dogs) achieved complete response, 2 of 18 (11%) achieved partial response, and 1 (6%) achieved stable disease at the end of the observation period, which was 40 months. Again, the treatment was more effective on smaller tumors (<2 cm). Compared with the literature data for recurrence rate after surgery or electrochemotherapy alone, it could be concluded that electrochemotherapy combined with interleukin-12 reduced the recurrence rate and prevented the development of distant metastases.82,97 Histologically, 8 weeks after treatment these tumors were infiltrated with macrophages, and a significant reduction in microvessels was observed.98 This treatment combination was also evaluated in oral malignant melanoma, one of the most common tumors in the oral cavity of elderly dogs, with a 2-month survival time if left untreated.99 Nine dogs were included, and 1 month after the treatment, the objective response rate was 67% and the median survival time was 6 months. Although the results were not as good as those in other tumor types and other locations, electrochemotherapy with interleukin-12 gene therapy may be beneficial when other modalities are not acceptable because of invasiveness or cost.

Another common tumor in the oral cavity of dogs is nontonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Eleven dogs were treated with electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin alone and one as an adjuvant to surgery. The objective response rate was higher than for melanoma, that is, 91% (10/11), with a median survival time of 3.5 months for dogs that responded partially (2/11) and 28 months for dogs that were killed owing to tumor-unrelated causes.100 A novel approach for the treatment of oral tumors of different histologies was proposed by Maglietti et al.,18 who performed the combined systemic and local administration of bleomycin. Sixty days after the treatment, the complete response rate to combined systemic and local bleomycin and electrochemotherapy was 54%, whereas in the control group receiving electrochemotherapy with systemic bleomycin only, partial responses were obtained in 19% dogs.18 The same group also proposed a single electrode approach for the treatment of tumors in the nasal cavity in dogs, which are difficult to reach using standard electrodes. The new approach was compared with standard treatment using surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy. After 1 year, 60% dogs that were treated with electrochemotherapy were still alive, whereas only 10% were alive in the surgical group, demonstrating that such an approach can be safely applied to the treatment of nasal duct tumors.101

Yet another application of electrochemotherapy in veterinary medicine is the treatment of sarcoids in horses. Although benign, sarcoids recur very quickly after surgery and are usually located in sensitive locations, such as the eyelids. Cisplatin in sesame oil is commonly used to treat such tumors; therefore, electrochemotherapy was also explored. Recently, a new study on 31 horses and 1 donkey was published, confirming the excellent results obtained previously, with a 100% complete response rate.102,103 Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin can be used alone, when tumors are small, or it can be used together with debulking surgery in cases of larger tumors. Calcium electroporation was also evaluated recently for the treatment of sarcoids. Tumors were treated with calcium electroporation and then surgically excised at different time points to determine the extent of necrosis, which was present in >50% of the tumor area in 9 of 13 treated sarcoids.104

Clinical Studies in Human Oncology

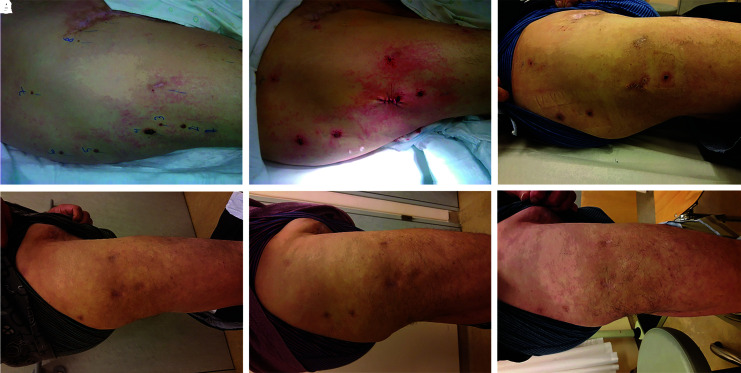

The most vivid field of electrochemotherapy is clinical. The results from almost 90 clinical trials or case reports were published in the past 5 years. A typical response of skin metastases to electrochemotherapy is the formation of a crust that eventually falls off, leaving a very good cosmetic effect (Fig. 1). Electrochemotherapy is becoming an established, well-recognized treatment option in Europe. Recently, electrochemotherapy was listed as a treatment option for localized lesions of Kaposi's sarcoma in European guidelines.105 Many of the publications are review articles and meta-analyses, which will further help to position electrochemotherapy among other local ablative therapies.106–108 Different aims were ascribed in these meta-analyses, including the determination of predictive factors in nonmelanoma skin cancer, cost-effectiveness, treatment efficacy, pain control, quality of life, and the role in the palliative management of cutaneous metastases.14,15,109–111

FIG. 1.

A typical response of melanoma skin metastases to electrochemotherapy treatment. The patient had a primary melanoma excised. Two years after the excision, metastases were present, and electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin was performed using needle row electrodes. Ten nodules were treated with electrochemotherapy, and one was excised for the determination of BRAF mutation. (A) Tumor nodules before electrochemotherapy; (B) immediately after the excision of one tumor nodule and electrochemotherapy of all other tumors; (C) 14 days after treatment; (D) 3 months after treatment; (E) 9 months after treatment; (F) 17 months after treatment.

In multivariate analysis of predictive factors regarding clinical pathological and instrumental predictors, only the tumor's site and appearance reached statistical significance, showing that this treatment can still be refined to achieve better treatment outcomes.111 All these excellent reviews present valuable data about the usefulness, effectiveness, safety, and patient compliance of electrochemotherapy. However, many clinical studies could not be included in systematic reviews because of the lack of information (data) in the published articles. To avoid this, recommendations for improving the quality of reporting clinical electrochemotherapy study results based on qualitative systematic review were published and should be implemented by the authors.12 Here, we will focus on new developments in electrochemotherapy that will lead to further development and dissemination of the therapy.

First, for subcutaneous as well as for deep-seated tumors, it is very important that the electric field coverage is adequate because this is a prerequisite for the permeabilization of cell membranes and the entry of the drug. Therefore, specifically for deep-seated tumors, treatment planning and radiological monitoring during the procedure to determine complete coverage of the treated tumor are of utmost importance.112,113 Namely, monitoring of changes during and after electrochemotherapy is important for evaluation of the progress of the procedure that is based on pretreatment plan and its results. It is important that tumor is not over treated as this will cause irreversible electroporation, or under treated (not enough cells exposed to electric field above threshold value) as this restricts the access of drugs into the cells and consequently their action on target, that is, DNA.112,113 For tumors in the head and neck region, the treatment plan can be coupled to the navigation system for accurate positioning of single long-needle electrodes into and around tumors.114

Furthermore, the new, sensitive method for the determination of bleomycin in serum and tumors enables a redefinition of the optimal therapeutic window for the application of electric pulses after bleomycin intravenous injection. Based on the pharmacokinetic data obtained in elderly patients (>65 years), the therapeutic window for bleomycin can be extended to up to 40 min.115 Furthermore, because of prolonged therapeutic concentrations in the serum, a lower dose of bleomycin can also be used, especially in elderly patients. Preliminary results demonstrated comparable effectiveness in nonmelanoma skin metastases in head and neck cancer,116 which was also confirmed for other types of skin tumors, that is, melanoma, breast cancer, and Kaposi's sarcoma.117

In addition to the standard chemotherapeutic drugs used in clinical electrochemotherapy, bleomycin and cisplatin, calcium chloride was evaluated in a clinical setting based on very promising preclinical results. A double-blinded phase II study was performed comparing the effect of calcium electroporation with electrochemotherapy. The treatment was performed on 47 cutaneous metastases from breast cancer and melanoma. The objective response rate 6 months after the treatment was 13 of 18 (72%) for calcium electroporation and 16 of 19 (84%) for electrochemotherapy, without a significant difference between the rates. Thus, calcium electroporation is feasible and effective in patients with cutaneous metastases.118 This finding is especially important in clinical environments, where the acquisition, handling, and waste disposal of antineoplastic drugs can present a challenge.

Recently, an updated, simplified version of standard operation procedures was published based on vast experience that was gained after the publication of the first standard operating procedures in 2006.11,119 The updated standard operating procedures are based on data from the treatment of many different histologies and increasing sizes (volume) of tumors that was originally thought to not be possible. The specialists from different fields, that is, oncology, general surgery, neck surgery, plastic surgery, and dermatology, prepared the recommendations for indications for electrochemotherapy, pretreatment information and evaluation, treatment choices and follow-up.119 These new standard operating procedures should enable further implementation of electrochemotherapy into national and European guidelines for the treatment of different types of tumors.

Future Perspectives and Conclusion

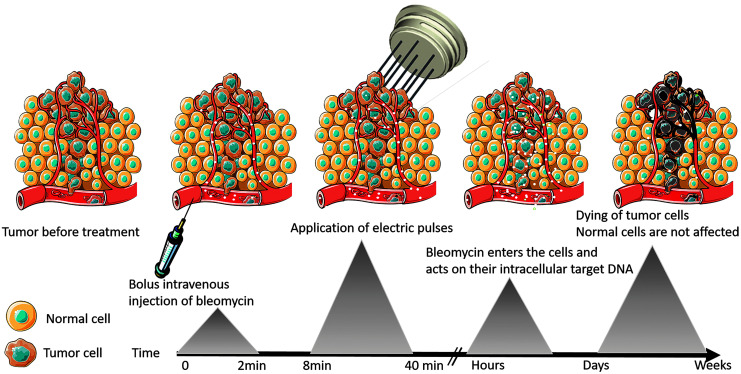

The main difference between electrochemotherapy and other local ablative therapies is that electrochemotherapy combines two modalities, chemotherapy and the application of electric pulses (Fig. 2). Thus, the tumor cells are dying not directly owing to the application of physical energy, such as in the case of other local ablative therapies, such as irreversible electroporation, radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, and cryoablation, but because of the action of chemotherapeutic drugs. This further means that the cells are dying in a more controllable way, either by apoptosis or other programmed types of cell death, resulting in a slower shrinkage of the tumor without the development of massive necrosis, which represents a major burden for patients and possesses a risk of further complications, such as infections. At present, at the preclinical level, much effort is devoted to evaluation of new combination of electrochemotherapy with other types of therapy and in new cancer entities and to development of so-called “painless electroporation.” In veterinary field, electrochemotherapy is gaining recognition in small animal practice, and is increasingly used for treatment of exotic companion animals, such as turtles, ferrets, and birds. At the clinical level, the most important advancement is the publication of results of bigger cohorts of patients with specific tumors, treated with electrochemotherapy. This is possible because of the clinical data repositories of several groups of institutions practicing electrochemotherapy. Future studies in preclinical and clinical electrochemotherapy will focus on deciphering the molecular mechanism that would identify tumors/patients that will benefit the most from electrochemotherapy and combinations either with different systemic treatments (immune, small molecule, or hormonal treatments) or with other local ablative therapies. Another very important field that still needs to be developed is percutaneous treatment by electrochemotherapy. First reports on the treatment of liver metastases from pancreatic cancer and for spine metastases have already been presented with encouraging results.120–122

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the timeline of the electrochemotherapy procedure and the response of tumor cells.

Author Contributions

M.C. designed the concept of the article and drafted it. G.S. critically revised it. Both coauthors have reviewed and approved the manuscript because submission.

Disclaimer

The funder had no role in the design, decision to publish, or preparation of the article. Language editing services for this article were provided by American Journal Experts. The article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS), grant No. P3-0003.

References

- 1.Mir LM, Orlowski S, Belehradek J, et al. Electrochemotherapy potentiation of antitumour effect of bleomycin by local electric pulses. Eur J Cancer 1991;27:68–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sersa G, Cemazar M, Miklavcic D, et al. Electrochemotherapy—variable antitumor effect on different tumor models. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg 1994;35:23–27 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heller R, Jaroszeski M, Messina J, et al. Treatment of B16 mouse melanoma with the combination of electropermeabilization and chemotherapy. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg 1995;36:83–87 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mir LM, Tounekti O, Orlowski S. Bleomycin: Revival of an old drug. Gen Pharmacol 1996;27:745–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sersa G, Cemazar M, Miklavcic D. Antitumor effectiveness of electrochemotherapy with cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) in mice. Cancer Res 1995;55:3450–3455 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilari D, Guancial E, Kim ES. Role of copper transporters in platinum resistance. World J Clin Oncol 2016;7:106–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belehradek J, Orlowski S, Poddevin B, et al. Electrochemotherapy of spontaneous mammary tumours in mice. Eur J Cancer 1991;27:73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudolf Z, Stabuc B, Cemazar M, et al. Electrochemotherapy with bleomycin. The first clinical experience in malignant melanoma patients. Radiol Oncol 1995;29:229–235 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heller R, Jaroszeski MJ, Glass LF, et al. Phase I/II trial for the treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous tumors using electrochemotherapy. Cancer 1996;77:964–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marty M, Sersa G, Garbay JR, et al. Electrochemotherapy—an easy, highly effective and safe treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases: Results of ESOPE (European Standard Operating Procedures of Electrochemotherapy) study. Eur J Cancer Suppl 2006;4:3–13 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mir LM, Gehl J, Sersa G, et al. Standard operating procedures of the electrochemotherapy: Instructions for the use of bleomycin or cisplatin administered either systemically or locally and electric pulses delivered by the Cliniporator (TM) by means of invasive or non-invasive electrodes. Eur J Cancer Suppl 2006;4:14–25 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campana LG, Clover AJP, Valpione S, et al. Recommendations for improving the quality of reporting clinical electrochemotherapy studies based on qualitative systematic review. Radiol Oncol 2016;50:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cemazar M, Sersa G, Frey W, et al. Recommendations and requirements for reporting on applications of electric pulse delivery for electroporation of biological samples. Bioelectrochemistry 2018;122:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campana LG, Miklavčič D, Bertino G, et al. Electrochemotherapy of superficial tumors—current status: Basic principles, operating procedures, shared indications, and emerging applications. Semin Oncol 2019;46:173–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campana LG, Edhemovic I, Soden D, et al. Electrochemotherapy—emerging applications technical advances, new indications, combined approaches, and multi-institutional collaboration. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:92–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miklavcic D.Handbook of Electroporation. 1st edition. New York, NY: Springer, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daeschlein G, Scholz S, Lutze S, et al. Comparison between cold plasma, electrochemotherapy and combined therapy in a melanoma mouse model. Exp Dermatol 2013;22:582–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maglietti F, Tellado M, Olaiz N, et al. Combined local and systemic bleomycin administration in electrochemotherapy to reduce the number of treatment sessions. Radiol Oncol 2016;50:58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calvet CY, Famin D, André FM, et al. Electrochemotherapy with bleomycin induces hallmarks of immunogenic cell death in murine colon cancer cells. Oncoimmunology 2014;3:e28131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vásquez JL, Ibsen P, Lindberg H, et al. In vitro and in vivo experiments on electrochemotherapy for bladder cancer. J Urol 2015;193:1009–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landström F, Ivarsson M, Von Sydow AK, et al. Electrochemotherapy—evidence for cell-type selectivity in vitro. Anticancer Res 2015;35:5813–5820 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saczko J, Pilat J, Choromanska A, et al. The effectiveness of chemotherapy and electrochemotherapy on ovarian cell lines in vitro. Neoplasma 2016;63:450–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esmekaya MA, Kayhan H, Coskun A, et al. Effects of cisplatin electrochemotherapy on human neuroblastoma cells. J Membr Biol 2016;249:601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dolinsek T, Prosen L, Cemazar M, et al. Electrochemotherapy with bleomycin is effective in BRAF mutated melanoma cells and interacts with BRAF inhibitors. Radiol Oncol 2016;50:274–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiorentzis M, Kalirai H, Katopodis P, et al. Electrochemotherapy with bleomycin and cisplatin enhances cytotoxicity in primary and metastatic uveal melanoma cell lines in vitro. Neoplasma 2018;65:210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel O, Kulbacka J, Saczko J, et al. Electroporation with cisplatin against metastatic pancreatic cancer: In vitro study on human primary cell culture. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prevc A, Niksic Zakelj M, Kranjc S, et al. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin or bleomycin in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Improved effectiveness of cisplatin in HPV-positive tumors. Bioelectrochemistry 2018;123:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tremble LF, O'Brien MA, Soden DM, et al. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin increases survival and induces immunogenic responses in murine models of lung cancer and colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett 2019;442:475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiorentzis M, Katopodis P, Kalirai H, et al. Conjunctival melanoma and electrochemotherapy: Preliminary results using 2D and 3D cell culture models in vitro. Acta Ophthalmol 2019;97:e632–e640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zakelj MN, Prevc A, Kranjc S, et al. Electrochemotherapy of radioresistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells and tumor xenografts. Oncol Rep 2019;41:1658–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drąg-Zalesińska M, Saczko J, Choromańska A, et al. Cisplatin and vinorelbine -mediated electrochemotherapeutic approach against multidrug resistant small cell lung cancer (H69AR) in vitro. Anticancer Res 2019;39:3711–3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandes P, O'Donovan TR, McKenna SL, et al. Electrochemotherapy causes caspase-independent necrotic-like death in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali MS, Gill KS, Saglio G, et al. Expressional changes in stemness markers post electrochemotherapy in pancreatic cancer cells. Bioelectrochemistry 2018;122:84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cemazar M, Todorovic V, Scancar J, et al. Adjuvant TNF-α therapy to electrochemotherapy with intravenous cisplatin in murine sarcoma exerts synergistic antitumor effectiveness. Radiol Oncol 2015;49:32–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremble LF, O'Brien MA, Forde PF, et al. ICOS activation in combination with electrochemotherapy generates effective anti-cancer immunological responses in murine models of primary, secondary and metastatic disease. Cancer Lett 2018;420:109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulbacka J, Daczewska M, Dubińska-Magiera M, et al. Doxorubicin delivery enhanced by electroporation to gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma cells with P-gp overexpression. Bioelectrochemistry 2014;100:96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudej R, Miklavcic D, Cemazar M, et al. Modulation of activity of known cytotoxic ruthenium(III) compound (KP418) with hampered transmembrane transport in electrochemotherapy in vitro and in vivo. J Membr Biol 2014;247:1239–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saczko J, Kamińska I, Kotulska M, et al. Combination of therapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin with electroporation in human ovarian carcinoma model in vitro. Biomed Pharmacother 2014;68:573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zielichowska A, Saczko J, Garbiec A, et al. The photodynamic effect of far-red range phthalocyanines (AlPc and Pc green) supported by electropermeabilization in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells of sensitive and resistant type. Biomed Pharmacother 2015;69:145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choromanska A, Kulbacka J, Rembialkowska N, et al. Effects of electrophotodynamic therapy in vitro on human melanoma cells—melanotic (MeWo) and amelanotic (C32). Melanoma Res 2015;25:210–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mittal L, Raman V, Camarillo IG, et al. Ultra-microsecond pulsed curcumin for effective treatment of triple negative breast cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;491:1015–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kranjc S, Cemazar M, Sersa G, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of electrochemotherapy with trans-platinum analogue trans-[PtCl2(3-Hmpy)2]. Radiol Oncol 2017;51:295–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ursic K, Kos S, Kamensek U, et al. Comparable effectiveness and immunomodulatory actions of oxaliplatin and cisplatin in electrochemotherapy of murine melanoma. Bioelectrochemistry 2018;119:161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartmann P, Butt E, Fehér Á, et al. Electroporation-enhanced transdermal diclofenac sodium delivery into the knee joint in a rat model of acute arthritis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018;12:1917–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mączyńska J, Choromańska A, Kutkowska J, et al. Effect of electrochemotherapy with betulinic acid or cisplatin on regulation of heat shock proteins in metastatic human carcinoma cells in vitro. Oncol Rep 2019;41:3444–3454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choromanska A, Kulbacka J, Harasym J, et al. Anticancer activity of oat β-glucan in combination with electroporation on uman cancer cells. Acta Pol Pharm 2017;74:616–623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weżgowiec J, Kulbacka J, Saczko J, et al. Biological effects in photodynamic treatment combined with electropermeabilization in wild and drug resistant breast cancer cells. Bioelectrochemistry 2018;123:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michel O, Przystupski D, Saczko J, et al. The favourable effect of catechin in electrochemotherapy in human pancreatic cancer cells. Acta Biochim Pol 2018;65:173–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garabalino MA, Olaiz N, Portu A, et al. Electroporation optimizes the uptake of boron-10 by tumor for boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) mediated by GB-10: A boron biodistribution study in the hamster cheek pouch oral cancer model. Radiat Environ Biophys 2019;58:455–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staresinic B, Jesenko T, Kamensek U, et al. Effect of calcium electroporation on tumour vasculature. Sci Rep 2018;8:9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frandsen SK, Gissel H, Hojman P, et al. Calcium electroporation in three cell lines: A comparison of bleomycin and calcium, calcium compounds, and pulsing conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2014;1840:1204–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frandsen SK, Gibot L, Madi M, et al. Calcium electroporation: Evidence for differential effects in normal and malignant cell lines, evaluated in a 3D spheroid model. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Falk H, Forde PF, Bay ML, et al. Calcium electroporation induces tumor eradication, long-lasting immunity and cytokine responses in the CT26 colon cancer mouse model. Oncoimmunology 2017;6:e1301332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romeo S, Sannino A, Scarfì MR, et al. ESOPE-equivalent pulsing protocols for calcium electroporation: An in vitro optimization study on 2 cancer cell models. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018;17:153303381878807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoejholt KL, Mužić T, Jensen SD, et al. Calcium electroporation and electrochemotherapy for cancer treatment: Importance of cell membrane composition investigated by lipidomics, calorimetry and in vitro efficacy. Sci Rep 2019;9:4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frandsen SK, Gehl J. Effect of calcium electroporation in combination with metformin in vivo and correlation between viability and intracellular ATP level after calcium electroporation in vitro. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frandsen SK, Krüger MB, Mangalanathan UM, et al. Normal and malignant cells exhibit differential responses to calcium electroporation. Cancer Res 2017;77:4389–4401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansen EL, Sozer EB, Romeo S, et al. Dose-dependent ATP depletion and cancer cell death following calcium electroporation, relative effect of calcium concentration and electric field strength. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedersoli F, Ritter A, Zimmermann M, et al. Single-needle electroporation and interstitial electrochemotherapy: In vivo safety and efficacy evaluation of a new system. Eur Radiol 2019;29:6300–6308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vera-Tizatl AL, Vera-Tizatl CE, Vera-Hernández A, et al. Computational feasibility analysis of electrochemotherapy with novel needle-electrode arrays for the treatment of invasive breast ductal carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018;17:153303381879493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campana LG, Dughiero F, Forzan M, et al. A prototype of a flexible grid electrode to treat widespread superficial tumors by means of electrochemotherapy. Radiol Oncol 2016;50:49–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Forde P, Sadadcharam M, Bourke M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of an endoscopic electroporation system. Endoscopy 2016;48:477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ongaro A, Campana LG, De Mattei M, et al. Effect of electrode distance in grid electrode: Numerical models and in vitro tests. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018;17:153303381876449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ongaro A, Campana LG, De Mattei M, et al. Evaluation of the electroporation efficiency of a grid electrode for electrochemotherapy: From numerical model to in vitro tests. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2016;15:296–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shankayi Z, Firoozabadi SM, Hassan ZS. Optimization of electric pulse amplitude and frequency in vitro for low voltage and high frequency electrochemotherapy. J Membr Biol 2014;247:147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spugnini EP, Melillo A, Quagliuolo L, et al. Definition of novel electrochemotherapy parameters and validation of their in vitro and in vivo effectiveness. J Cell Physiol 2014;221:1177–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kranjc S, Kranjc M, Scancar J, et al. Electrochemotherapy by pulsed electromagnetic field treatment (PEMF) in mouse melanoma B16F10 in vivo. Radiol Oncol 2016;50:39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scuderi M, Rebersek M, Miklavcic D, et al. The use of high-frequency short bipolar pulses in cisplatin electrochemotherapy in vitro. Radiol Oncol 2019;53:194–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcia-Sanchez T, Mercadal B, Polrot M, et al. Successful tumor electrochemotherapy using sine waves. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2019; [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1109/TBME.2019.2928645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahna A, Firoozabadi SMP, Shankayi Z. The effect of ELF magnetic field on tumor growth after electrochemotherapy. J Membr Biol 2014;247:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dermol J, Miklavčič D. Mathematical models describing chinese hamster ovary cell death due to electroporation in vitro. J Membr Biol 2015;248:865–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forjanič T, Miklavčič D. Mathematical model of tumor volume dynamics in mice treated with electrochemotherapy. Med Biol Eng Comput 2017;55:1085–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cindrič H, Kos B, Tedesco G, et al. Electrochemotherapy of spinal metastases using transpedicular approach—a numerical feasibility study. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018;17:153303461877025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhonsle S, Lorenzo MF, Safaai-Jazi A, et al. Characterization of nonlinearity and dispersion in tissue impedance during high-frequency electroporation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2018;65:2190–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldberg E, Suárez C, Alfonso M, et al. Cell membrane electroporation modeling: A multiphysics approach. Bioelectrochemistry 2018;124:28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dermol-Černe J, Vidmar J, Ščančar J, et al. Connecting the in vitro and in vivo experiments in electrochemotherapy—a feasibility study modeling cisplatin transport in mouse melanoma using the dual-porosity model. J Control Release 2018;286:33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berkenbrock JA, Machado RG, Suzuki DOH. Electrochemotherapy effectiveness loss due to electric field indentation between needle electrodes: A numerical study. J Healthc Eng 2018;2018:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pintar M, Langus J, Edhemović I, et al. Time-dependent finite element analysis of in vivo electrochemotherapy treatment. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018;17:153303381879051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kranjc M, Markelc B, Bajd F, et al. In situ monitoring of electric field distribution in mouse tumor during electroporation. Radiology 2015;274:115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Josserand V, Kéramidas M, Lavaud J, et al. Electrochemotherapy guided by intraoperative fluorescence imaging for the treatment of inoperable peritoneal micro-metastases. J Control Release 2016;233:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kosjek T, Krajnc A, Gornik T, et al. Identification and quantification of bleomycin in serum and tumor tissue by liquid chromatography coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry. Talanta 2016;160:164–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kodre V, Cemazar M, Pecar J, et al. Electrochemotherapy compared to surgery for treatment of canine mast cell tumours. In Vivo 2009;23:55–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tozon N, Lampreht Tratar U, Znidar K, et al. Operating procedures of the electrochemotherapy for treatment of tumor in dogs and cats. J Vis Exp 2016;16:54760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tozon N, Milevoj N, Lampreht Tratar U, et al. Veterinary workshop on electroporation-based treatments. In: 3rdWorld Congress on Electroporation and Pulsed Electric Fields in Biology, Medicine, and Food and Environmental Technologies, Toulouse, France. 2019, p. 95 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brunner CHM, Dutra G, Silva CB, et al. Electrochemotherapy for the treatment of fibropapillomas in Chelonia mydas. J Zoo Wildl Med 2014;45:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lanza A, Baldi A, Spugnini EP. Surgery and electrochemotherapy for the treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a yellow-bellied slider (Trachemys scripta scripta). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015;246:455–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lanza A, Pettorali M, Baldi A, et al. Surgery and electrochemotherapy treatment of incompletely excised mammary carcinoma in two male pet rats (Rattus norvegicus). J Vet Med Sci 2017;79:623–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Racnik J, Svara T, Zadravec M, et al. Electrochemotherapy with bleomycin of different types of cutaneous tumours in a ferret (Mustela putorius furo). Radiol Oncol 2017;52:98–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Racnik J, Svara T, Zadravec M, et al. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin for the treatment of a non-operable cutaneous fibroma in a cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus). N Z Vet J 2019;67:155–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Spugnini EP, Lanza A, Sebasti S, et al. Electrochemotherapy palliation of an oral squamous cell carcinoma in an African hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). Vet Res Forum 2018;9:379–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Donnelly KA, Papich MG, Zirkelbach B, et al. Plasma bleomycin concentrations during electrochemotherapeutic treatment of fibropapillomas in green turtles Chelonia mydas. J Aquat Anim Health 2019;31:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tozon N, Pavlin D, Sersa G, et al. Electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin injection: An observational study in superficial squamous cell carcinoma in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2014;16:291–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spugnini EP, Pizzuto M, Filipponi M, et al. Electroporation enhances bleomycin efficacy in cats with periocular carcinoma and advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head. J Vet Intern Med 2015;29:1368–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Torrigiani F, Pierini A, Lowe R, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma in dogs: A treatment review and a novel approach using electrochemotherapy in a case series. Vet Comp Oncol 2019;17:234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spugnini EP, Vincenzi B, Amadio B, et al. Adjuvant electrochemotherapy with bleomycin and cisplatin combination for canine soft tissue sarcomas: A study of 30 cases. Open Vet J 2019;9:88–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lowe R, Gavazza A, Impellizeri JA, et al. The treatment of canine mast cell tumours with electrochemotherapy with or without surgical excision. Vet Comp Oncol 2017;15:775–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cemazar M, Ambrozic Avgustin J, Pavlin D, et al. Efficacy and safety of electrochemotherapy combined with peritumoral IL-12 gene electrotransfer of canine mast cell tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 2017;15:641–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Salvadori C, Svara T, Rocchigiani G, et al. Effects of electrochemotherapy with cisplatin and peritumoral IL-12 gene electrotransfer on canine mast cell tumors: A histopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Radiol Oncol 2017;51:286–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harvey HJ, MacEwen EG, Braun D, et al. Prognostic criteria for dogs with oral melanoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1981;178:580–582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Simčič P, Lowe R, Granziera V, et al. Electrochemotherapy in treatment of canine oral non-tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. a case series report. Vet Comp Oncol 2019;[Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1111/vco.12530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maglietti F, Tellado M, Olaiz N, et al. Minimally invasive electrochemotherapy procedure for treating nasal duct tumors in dogs using a single needle electrode. Radiol Oncol 2017;51:422–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tozon N, Kramaric P, Kos Kadunc V, et al. Electrochemotherapy as a single treatment or adjuvant treatment to surgery of cutaneous sarcoid tumours in horses: A 31-case retrospective study. Vet Rec 2016;179:627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tamzali Y, Borde L, Rols MP, et al. Successful treatment of equine sarcoids with cisplatin electrochemotherapy: A retrospective study of 48 cases. Equine Vet J 2012;44:214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Galant L, Delverdier M, Lucas M-N, et al. Calcium electroporation: The bioelectrochemical treatment of spontaneous equine skin tumors results in a local necrosis. Bioelectrochemistry 2019;129:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lebbe C, Garbe C, Stratigos AJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi's sarcoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline (EDF/EADO/EORTC). Eur J Cancer 2019;114:117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cadossi R, Ronchetti M, Cadossi M. Locally enhanced chemotherapy by electroporation: Clinical experiences and perspective of use of electrochemotherapy. Futur Oncol 2014;10:877–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Campana LG, Testori A, Mozzillo N, et al. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with electrochemotherapy. J Surg Oncol 2014;109:301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.De Virgilio A, Fusconi M, Greco A, et al. The role of electrochemotherapy in the treatment of metastatic head and neck cancer. Tumori 2013;99:634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.De Virgilio A, Ralli M, Longo L, et al. Electrochemotherapy in head and neck cancer: A review of an emerging cancer treatment (Review). Oncol Lett 2019;17:1253–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Quaglino P, Matthiessen LW, Curatolo P, et al. Predicting patients at risk for pain associated with electrochemotherapy. Acta Oncol 2015;54:298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rotunno R, Paolino G, Cantisani C, et al. Predictive factors in non-melanoma skin cancers treated with electrochemotherapy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2018;153:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Marčan M, Pavliha D, Kos B, et al. Web-based tool for visualization of electric field distribution in deep-seated body structures and planning of electroporation-based treatments. Biomed Eng Online 2015;14:S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Boc N, Edhemovic I, Kos B, et al. Ultrasonographic changes in the liver tumors as indicators of adequate tumor coverage with electric field for effective electrochemotherapy. Radiol Oncol 2018;52:383–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Groselj A, Kos B, Cemazar M, et al. Coupling treatment planning with navigation system: A new technological approach in treatment of head and neck tumors by electrochemotherapy. Biomed Eng Online 2015;14:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Groselj A, Krzan M, Kosjek T, et al. Bleomycin pharmacokinetics of bolus bleomycin dose in elderly cancer patients treated with electrochemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2016;77:939–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Groselj A, Bosnjak M, Strojan P, et al. Efficiency of electrochemotherapy with reduced bleomycin dose in the treatment of nonmelanoma head and neck skin cancer: Preliminary results. Head Neck 2018;40:120–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rotunno R, Campana LG, Quaglino P, et al. Electrochemotherapy of unresectable cutaneous tumours with reduced dosages of intravenous bleomycin: Analysis of 57 patients from the International Network for Sharing Practices of Electrochemotherapy registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32:1147–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Falk H, Matthiessen LW, Wooler G, et al. Calcium electroporation for treatment of cutaneous metastases; a randomized double-blinded phase II study, comparing the effect of calcium electroporation with electrochemotherapy. Acta Oncol 2018;57:311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gehl J, Sersa G, Matthiessen LW, et al. Updated standard operating procedures for electrochemotherapy of cutaneous tumours and skin metastases. Acta Oncol 2018;57:874–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cornelis FH, Korenbaum C, Ben Ammar M, et al. Multimodal image-guided electrochemotherapy of unresectable liver metastasis from renal cell cancer. Diagn Interv Imaging 2019;100:309–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cornelis FH, Ben Ammar M, Nouri-Neuville M, et al. Percutaneous image-guided electrochemotherapy of spine metastases: Initial experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2019;42:1806–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Djokic M, Badovinac D, Petric M, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with electrochemotherapy. In: 3rdWorld Congress on Electroporation and Pulsed Electric Fields in Biology, Medicine, and Food and Environmental Technologies, Toulouse, France. 2019, p. 143 [Google Scholar]