BACKGROUND

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many workplaces closed and some workers were able to telework for the first time. Disparities in who remained in workplaces may have contributed to COVID-19 disparities.1

One study identified an association between inability to telework and SARS-CoV-2 infection.2 Pre-pandemic, whites worked remotely more frequently than minorities.3 Trends in teleworking during the pandemic are less clear, however, as are the implications of such disparities for members of workers’ households at increased risk of severe COVID-19.

METHODS

We analyzed the May 2020–February 2021 Current Population Surveys (CPS) (obtained via IPUMS4) which asked: “At any time in the last 4 weeks, did (you/name) telework or work at home for pay because of the coronavirus pandemic?” (Workers already working from home before the pandemic were categorized “no”).

We examined monthly trends in teleworking among adults 18–64 years who had a job and were at work the preceding week, and differences in teleworking in May 2020 and February 2021 by workers’ region; age; sex; race/ethnicity; immigration status; education; family income; and disability status. We examined differences by presence in workers’ households of individuals at elevated risk of severe COVID-19, including disabled individuals (among workers themselves not disabled) and adults ages ≥65, 75, or 85 years.

We used STATA/SE 16.1, CPS’ weights, Davern’s method5 to calculate approximate standard errors,6 and Pearson’s chi-square tests.

RESULTS

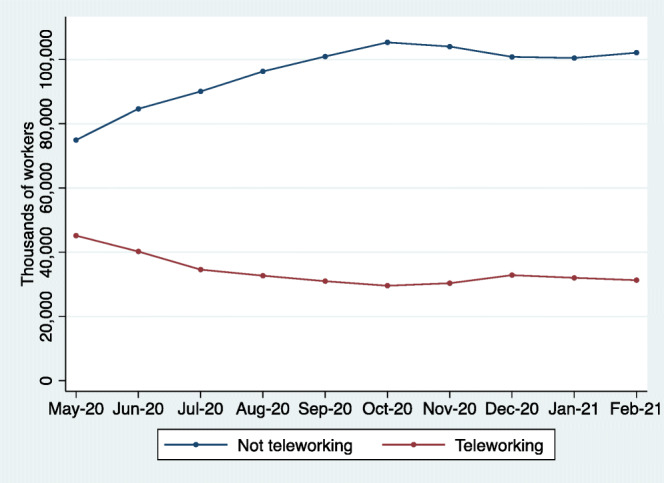

Our sample included n=410,248 individuals. Figure 1 shows employment trends by telework status. In May 2020, a weighted 45.2 million workers (37.6% of those at work) were teleworking due to the COVID-19 pandemic, while 74.9 million (62.4%) were not newly teleworking. The number working but not teleworking rose to 105.3 million in October 2020, falling slightly to 102.1 million in February 2021, when 31.3 million were teleworking (23.5% of those employed).

Fig. 1.

Trends in teleworking due to COVID-19 among workers aged 18–64, May 2020–February 2021 (unweighted n=410,248). Note: Figure estimates are weighted to be nationally representative. Individuals who telecommute, but who are not teleworking due to the COVID-19 pandemic, are classified as “not teleworking for COVID-19.” Figures only include current workers (defined as having a job in the previous week).

In February 2021, the 5 jobs with the most teleworkers were managers, software developers, elementary/middle school teachers, accountants/auditors, and customer service representatives. The jobs with the most individuals working (but not teleworking) were driver/sales workers and truck drivers; managers; nurses; first-line supervisors/managers of retail sales workers; and retail sales person.

Table 1 presents characteristics of teleworkers in May 2020 and February 2021. In both months, workers in New England were most likely to be teleworking, while those in East South Central states least likely (p<0.01). Black and Hispanic, compared to white workers, were less likely to be teleworking in both months; those of other/multiple race were more likely (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Percentage of Employed Individuals Teleworking due to COVID-19 by Individual and Family Characteristics, May and November 2020

| May 2020 (n=35,436) | February 2020 (n=43,802) | |

|---|---|---|

| Census region/division | ||

| New England | 47.2 | 35.0 |

| Middle Atlantic | 46.4 | 30.3 |

| East North Central | 36.5 | 22.4 |

| West North Central | 33.1 | 19.9 |

| South Atlantic | 36.6 | 20.9 |

| East South Central | 27.5 | 14.4 |

| West South Central | 33.2 | 18.1 |

| Mountain | 35.9 | 21.3 |

| Pacific | 40.7 | 28.8 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Age | ||

| Age 18–24 | 20.2 | 9.5 |

| Age 25–54 | 40.5 | 25.8 |

| Age 55+ | 36.2 | 23.2 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 40.6 | 25.1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 30.9 | 20.6 |

| Hispanic | 24.3 | 13.8 |

| Non-Hispanic Other/Multiple | 51.4 | 35.3 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 32.2 | 21.1 |

| Female | 44.0 | 26.1 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Immigrant status† | ||

| Not immigrant | 38.6 | 23.8 |

| Immigrant | 33.0 | 21.9 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Education | ||

| HS or less | 12.6 | 6.3 |

| Some college | 25.0 | 14.3 |

| BA + | 62.3 | 41.9 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Income | ||

| <$25K | 17.2 | 8.6 |

| $25–$49K | 20.2 | 10.7 |

| $50–$74 | 28.7 | 17.1 |

| $75–99K | 36.4 | 21.4 |

| $100–$14 | 44.9 | 29.5 |

| $150K+ | 57.3 | 41.6 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Functional disability‡ | ||

| No difficulty | 37.9 | 23.5 |

| Has difficulty | 28.9 | 21.6 |

| p value | <0.01 | 0.17 |

| Family size | ||

| < 6 | 38.6 | 24.1 |

| ≥6 | 22.7 | 12.0 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Oldest household (HH) adult | ||

| Oldest HH adult < 65 years | 38.4 | 23.9 |

| Oldest HH adult ≥65 years | 29.8 | 19.3 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Oldest HH adult < 75 years | 37.9 | 23.5 |

| Oldest HH adult ≥75 years | 28.8 | 20.5 |

| p value | <0.01 | 0.04 |

| Oldest HH adult < 85 years | 37.7 | 23.5 |

| Oldest HH adult ≥85 years | 33.6 | 23.4 |

| p value | 0.25 | 0.98 |

| Disabled individual in household§ | ||

| None | 38.7 | 24.0 |

| 1+ | 28.2 | 17.2 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

HH household

*We simplified the CPS’ self-reported race variable into three categories: White, Black, and Other (including individuals of multiple races), and created a forth category to indicate Hispanic individuals of any race

†Immigrants defined as those “foreign born” regardless of citizenship status; a small number coded as unknown birth place/parentage were excluded. Foreign born includes those born in outlying US possessions/territories. Number analyzed: n=35,409 in May and n=43,762 in February

‡Defined as those with one or more of 6 disabilities: difficulties hearing, difficulties seeing (even with corrective lenses), cognitive difficulties, serious difficulties with walking or stairs, condition lasting 6+ months impeding basic activities outside home without aid, condition lasting 6+ months impeding care of personal needs inside the home

§Defined same as functional disability. These analyses exclude workers who themselves have a disability. Number analyzed: n=34,298 in May and n=42,370 in February

Men, immigrants, and workers with less education or lower incomes were less likely to be teleworking (p<0.01). For instance, in February, 41.6% of those with family incomes ≥$150,000 teleworked due to COVID-19 vs. 8.6% of those earning <$25,000.

Workers in large (vs. smaller) families were less likely to be teleworking in both months (p<0.01). Workers in households with one or more adults ≥65 years were also less likely to be teleworking (p<0.05), as were workers with disabilities (in May) and those living with disabled individuals (p<0.01).

CONCLUSIONS

Up to 30 million individuals may have returned to the workplace after the initial COVID-19 wave. There were disparities in who remained in the workplace, and implications for families: those employed but not teleworking lived in larger families and were more likely to live with individuals at increased risk of severe COVID-19.

Our findings complement analyses suggesting that occupational exposures contributed to COVID-19 disparities,1, 2 and that teleworking (and workplace closures for “non-essential” jobs that cannot be performed from home) may have been underutilized during the pandemic, especially during the severe surge this winter. For physicians, these findings underscore the importance of occupational history in assessing COVID-19 risk, not merely of patients but of their family members.

Our study has limitations. CPS’ definition of teleworking excludes those teleworking prior to COVID-19, causing us to underestimate the prevalence of teleworking and disparities in teleworking.3 We do not know whether those reporting teleworking were working from home at all times, or only sometimes. We also lacked data on COVID-19 incidence in our sample.

Workplace closures are an important public health intervention in the face of respiratory pandemics. Policies should increase equity in teleworking during pandemics, ensure support for displaced workers, and mandate adequate protections for those who remain in the workplace.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Adam W Gaffney, Email: agaffney@challiance.org.

David U. Himmelstein, Email: dhimmels@hunter.cuny.edu.

Steffie Woolhandler, Email: swoolhan@hunter.cuny.edu.

References

- 1.Mutambudzi M, Niedwiedz C, Macdonald EB, et al.Occupation and risk of severe COVID-19: prospective cohort study of 120 075 UK Biobank participants. Occup Environ Med. Published online December 1, 2020. 10.1136/oemed-2020-106731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Fisher KA. Telework Before Illness Onset Among Symptomatic Adults Aged ≥18 Years With and Without COVID-19 in 11 Outpatient Health Care Facilities — United States, July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Not everybody can work from home: Black and Hispanic workers are much less likely to be able to telework. Economic Policy Institute. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://www.epi.org/blog/black-and-hispanic-workers-are-much-less-likely-to-be-able-to-work-from-home/

- 4.Flood S, King M, Rodgers R, Ruggles JR. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 7.0 [Dataset]. IPUMS; 2020. 10.18128/D030.V7.0

- 5.Davern M, Jones A, Lepkowski J, Davidson G, Blewett LA. Estimating Regression Standard Errors with Data from the Current Population Survey’s Public Use File. INQUIRY. 2007;44(2):211–224. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_44.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savych B, Klerman JA, Loughran DS. Recent Trends in Veteran Unemployment as Measured in the Current Population Survey and the American Community Survey. RAND National Defense Research Institute; 2008.