Abstract

A third survey of the practice of licensed psychologists during the pandemic conducted in June 2021 revealed that the rapid adoption of telepsychological service provision has continued approximately 15 months after a national public health emergency was declared. Most respondents intend to make telepsychology a permanent component of their practice going forward. Other notable findings from our survey revealed that after an initial decline in caseload reported in the early days of the pandemic, the majority of psychologists surveyed now report an increase in caseload, often necessitating the establishment of a waitlist. Respondents reported that their patients/clients are more accepting of telepsychology than in our previous survey. That said, a significant minority of psychologists expressed concerns that this technology will negatively affect their future practice. Results also indicated that psychologists are encountering greater symptom acuity among their patients associated with the pandemic, including an increase in reports of suicidal thinking or behavior.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42843-021-00044-3.

Introduction

Of the many societal changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to distance provision of healthcare services, including psychological services, has been among the most profound. In general, the provision of any kind of care via telehealth increased from less than 1% in 2018 to over 16% in April 2020, with demand for distance behavioral health services significantly driving these numbers (Volk et al., 2021). In recent months, national estimates indicate that the percentage of adults aged 18 and over who utilize telehealth surpassed 20% (National Center for Health Statistics, 2021).

This profound shift was aided by enabling regulations or executive actions taken by various states, with 22 states enacting changes expanding telehealth during the pandemic. Major foci of such moves were requirements to cover audio-only services and parity for patient cost and provider reimbursement for telehealth services. It is important to note, however, that approximately two-thirds of these actions were temporary only, generally via emergency order. Only eight states passed legislation permanently changing the status of telehealth reimbursement (Volk et al., 2021).

In two previous papers, we reported on changes in services provided by licensed psychologists during the COVID-19 pandemic. These surveys were conducted immediately (late March/early April 2020) after the public health emergency was declared and again at what may be considered a mid-point of the pandemic (September 2020). The surveys found a rapid, significant shift by respondents to telepsychology service delivery (Sammons et al., 2020a, b). In brief, these surveys were convenience samples of licensed psychologists who were members of the National Register of Health Service Psychologists or psychologists who have professional liability insurance offered by The Trust. Each survey had more than 3,000 unique respondents. In the current report, we describe the results of the third survey of licensed psychologists conducted in June 2021. Our findings regarding the shift to telepsychology are extended. We report on psychologists’ changing perceptions of practice in a post-pandemic era.

Method

As in our two previous surveys conducted in March/April and September 2020, we used a convenience sample of psychologists who obtained their professional liability insurance from The Trust or were current holders of the National Register’s Health Service Psychologist credential. The present survey was conducted June 1–21, 2021, when many healthcare providers were beginning to consider re-establishing in-person services.

We sent two email reminders to potential participants. Using the total number of email recipients who had opened an email invitation (n = 31,593) and the total of 2807 usable responses, a total response rate of 8.9% was achieved. While lower than the response rates for our two previous surveys (13.6% for each), we believe the responses are sufficient to be interpreted.

We note that multiple responses were allowed for some of our questions (notably questions 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, and 13; see Electronic Supplementary Material). Also, we included in our results returned surveys where respondents had skipped questions. Thus, the total number of calculated responses to any one question may have been less or greater than the total number of responses to the entire survey.

Results and Comparison with Earlier Surveys

Demographic variables were similar to those reported in our earlier surveys: Approximately three-quarters of respondents (77.5%) were employed in solo or group private practice settings. Most respondents were senior clinicians, with 52.6% reporting over 26 years of practice experience, and the remaining half divided roughly equally between those claiming from less than one to 25 years of practice. These characteristics were generally consistent with the results of our previous surveys. Ninety-five percent (n = 2771) of respondents reported being fully vaccinated at the time of survey completion. A small minority (3%) stated that they did not intend to become vaccinated. As expected, COVID-19 had a direct personal effect on the majority of respondents: Fifty-two percent (n = 2788) reported knowing family members or close friends or colleagues who had contracted the illness, and 9% reported the death of family members or close friends or colleagues. Less than 4% of all respondents had contracted the disease.

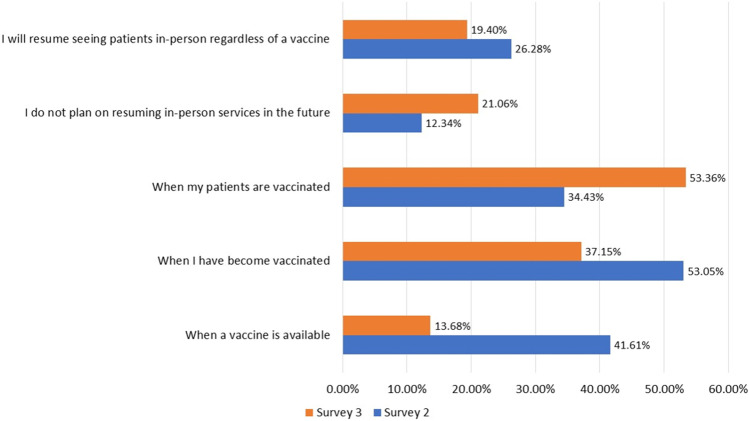

Our survey was conducted when many jurisdictions were lifting restrictions on gatherings and social distancing protocols. In this context, we queried respondents regarding plans to resume in-person services (Fig. 1). Approximately 37% (n = 2412) of respondents reported they would do so when they were fully vaccinated, 53% reported they would do so when their patients had become fully vaccinated, and 19% said they would resume in-person services regardless of vaccination status. Roughly 21% of respondents reported they had no intention of resuming any kind of in-person services.

Fig. 1.

Conditions required to reopen in-person practice

Almost all respondents reported their intention to employ some version of a safety protocol upon resuming in-person services (n = 2629), with respondents evenly split between the types of protocol. These included a combination of social distancing, sanitization, and mask-wearing by patients and/or providers.

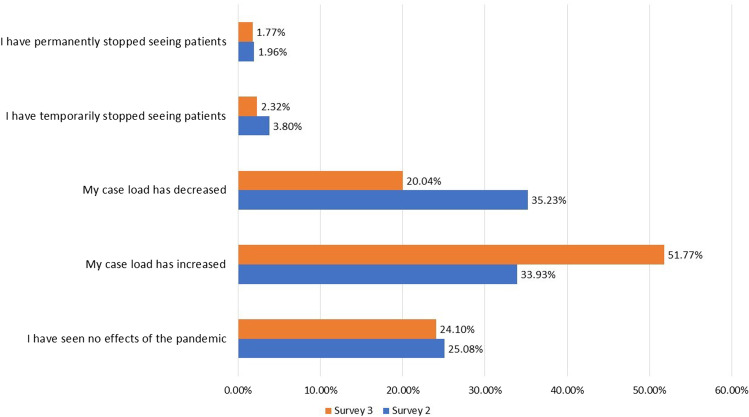

Increased Caseloads and Symptom Acuity as a Result of the Pandemic

A slim majority of our respondents (52%, n = 2764) reported an increase in caseload since the beginning of the pandemic. Of those reporting increased caseloads, most (72.6%) described varied increases of 10–40% since the pandemic began. Contrariwise, 20% reported a decrease in caseload. Of respondents reporting a decreased caseload, most reported a decrease of 20–29%. These numbers stand in contrast to results from our second survey in September 2020, when 35% of respondents noted a decrease in patient caseload (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of the pandemic on caseload, September 2020 and June 2021

Overall, 61% (n = 1424) of respondents who reported an increased caseload also reported that they established a waiting list to accommodate the increased demand for services. We did not inquire whether this was due to limitations imposed by telepsychology requirements or if this was due to other factors.

Approximately one-third of respondents (34%, n = 2722) reported that more of their patients/clients reported elevated symptoms of emotional distress than before the pandemic. A roughly equivalent percentage (37%) reported an increase in patients complaining of symptoms of chronic stress than before the pandemic. Eleven percent of respondents reported more patients/clients with suicidal thinking or behavior than before the pandemic.

These troubling findings complement ongoing data collections from the U.S. Census Bureau (2021), which found that between June 9–21, approximately 30% of adults in the United States reported symptoms of generalized anxiety or major depressive disorders, including about 45% of young adults between the ages of 18–29. Comparatively, in 2019, the National Health Interview Survey reported that about 11% of adults aged 18 and over had symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder (Terlizzi & Schiller, 2021). Although the overall number of completed suicides decreased in 2020, recent research indicates rates may have been higher among populations who were disproportionately harmed by the pandemic, such as many underrepresented people in the United States (Bray et al., 2021).

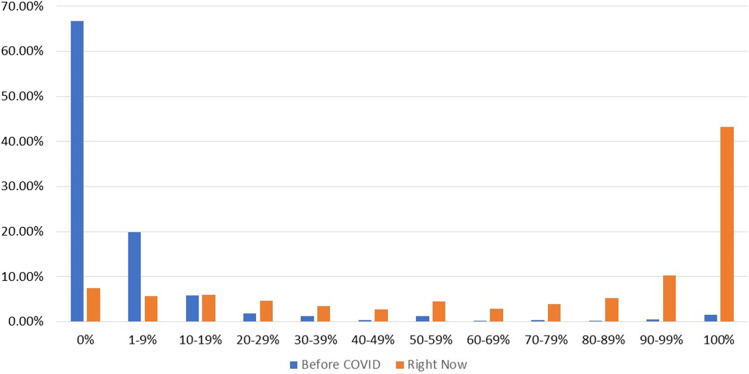

Shift Toward Telepsychological Practice

The epochal shift to telepsychology resulting from the pandemic occurred early. Our previous survey conducted in March/April 2020 found that over three-quarters of respondents had transitioned almost entirely to telepsychology. This shift was similarly observed during our second survey in September 2020. Yet again, our most recent survey is in keeping with these prior data. Respondents to the current survey indicated that 67% (n = 2726) had provided no telepsychological services before March 2020. Even among those providing such services before the pandemic, telepsychology usually accounted for less than 20% of their caseload. A hybrid model soon evolved. Our prior surveys discovered that in March/April 2020, most respondents (54%) were conducting over 90% of their caseload using telepsychology. In September, 68% of respondents saw all or almost all of their caseload via telepsychology. While telepsychology still predominates, the number of respondents relying entirely on distance service provision appears to have declined since the height of the pandemic (Fig. 3). In June 2021, 54% of respondents saw over 90% of their caseload via telepsychology.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of caseload seen via telepsychology

Only 6% saw their entire caseload in person (we did not inquire as to the absolute numbers of patients seen). Whether in-person or remote, most services were provided to adults (35%, n = 2619), followed by seniors (20%), adolescents (16%), and couples (12%).

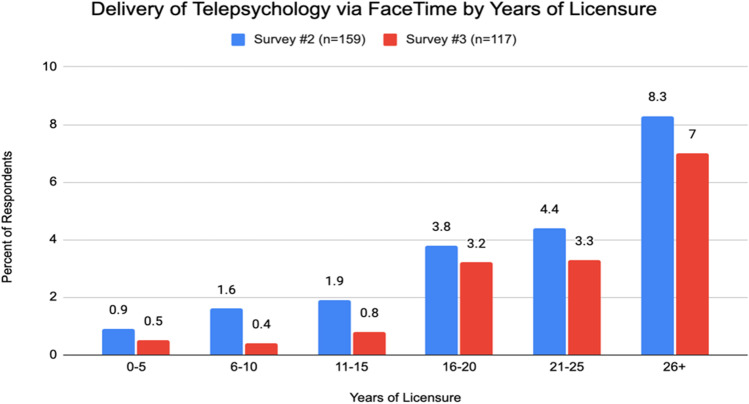

Telepsychology Platform

Zoom and doxy.me, both with HIPAA-compliant capabilities, were the most popular internet platforms employed by psychologists (29% and 27% respectively, n = 2631). We noticed a tendency for more senior psychologists to use telepsychology applications that might not be HIPAA compliant (e.g., FaceTime). Our survey in September 2020 showed that psychologists with 26 or more years of experience were significantly more likely to report that they most frequently used FaceTime to provide telepsychological services compared to earlier-career peers (χ2(5, n = 156) = 319.6, p < 0.01), potentially because more experienced psychologists in that sample were more likely to work in a solo or group private practice (Sammons et al., 2020a). The results of the current survey similarly conclude that psychologists with 26 or more years of experience are significantly more likely to use FaceTime to provide telepsychological care than early career psychologists (χ2(2, n = 113) = 129.8, p < 0.01). Over the course of our surveys, however, the percentage of health service psychologists who most frequently used FaceTime to provide telepsychological care appeared to decrease slightly at all levels of licensure experience (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Telepsychology via facetime by years of licensure, September 2020 and June 2021

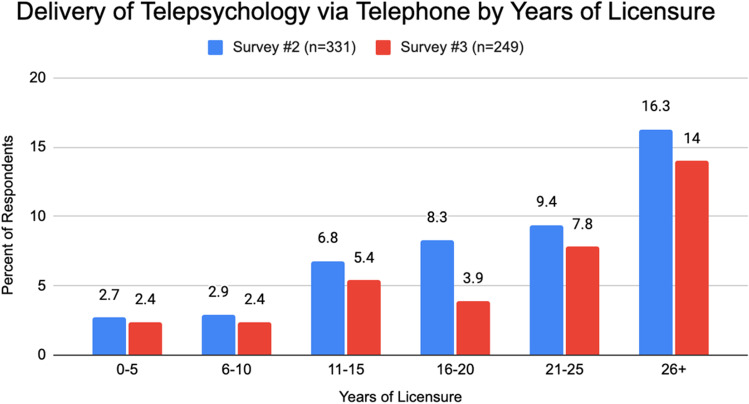

Audio-Only Telepsychology (i.e., Telephone)

In our September 2020 survey, we also noted that using a telephone to provide audio-only telepsychology services appeared to increase as a function of years in practice (Sammons et al. 2020a). Data from the current survey (Fig. 5) reflect that psychologists with 26 or more years of experience continued to be significantly more likely to use a telephone frequently to provide telepsychological services than early career psychologists (χ2(5, n = 249) = 659.87, p < 0.01). As has been stated, a psychologist’s proclivity to utilize a particular telepsychological modality is likely influenced by several variables such as work setting. Similar to the use of potentially HIPAA non-compliant platforms, the percentage of health service psychologists in these samples who most frequently used a telephone to provide telepsychological care decreased slightly at all levels of licensure experience.

Fig. 5.

Delivery of services via telephone, September 2020 and June 2021

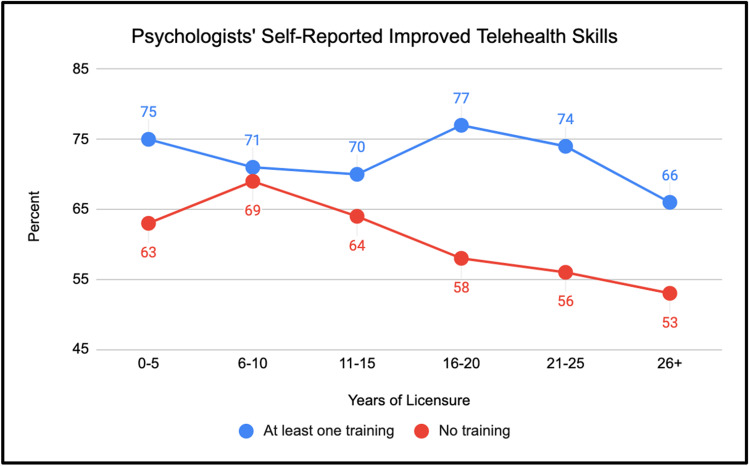

Respondents’ Skills Ratings

Respondents noted that their skills as a telehealth provider had improved over the course of the pandemic. Sixty-three percent reported that their skills had improved “a good amount” or “a great deal” (n = 1624), while 30% reported at least some skills improvement. Fifty-four percent (n = 1386) reported attending at least one telepsychology training session offered by the National Register or The Trust (n = 949). Among these data, when respondents were presented with the question, “since the beginning of COVID-19, do you believe your skills as a telehealth provider have improved?”, psychologists who attended at least one training session appeared more likely to indicate their skills had improved “a good amount” or “a great deal” than psychologists who hadn’t attended at least one training session. For example, a logistic regression indicated that the odds of a respondent reporting their skills as a telehealth provider improved either “a good amount” or “a great deal” were 1.72 times higher for providers who attended at least one training session, compared to zero training sessions (95% CI: 1.46–2.03, p < 0.01).

While noting this finding holds at every level of licensure experience (as shown in Fig. 6), we make no causal attributions about the effect of any training session offered by the National Register or The Trust on psychologists’ self-reported telehealth skills. Indeed, more research is needed to further examine this finding and other potential explanatory variables (e.g., time, selection bias).

Fig. 6.

Improvement in telepsychology skills

Optimism Regarding the Future

Most psychologists reported feeling optimistic about how the growing use of telepsychology may affect their practice at each level of licensure experience. However, when queried more globally about the potential implications of telepsychological health service provision and the future of their practices, respondents were less resoundingly upbeat with a mixture of neutral, optimistic, and pessimistic attitudes.

While not entirely clear, one potential explanation is that psychologists generally view the growth of telepsychology during the pandemic as advantageous because it increases accessibility to patients, thus providing a means to generate revenue that might otherwise be less accessible. For instance, we discovered that most psychologists believed telepsychology had expanded their accessibility to patients/clients, with 79% (n = 2701) agreeing or strongly agreeing with this statement. But these more positive elements of telepsychology do not appear to sway psychologists’ more nuanced global attitudes unilaterally. For example, on a separate item, 18% of respondents reported that lack of patient/client access to appropriate internet services and equipment hampered their ability to provide telepsychological care, potentially confirming the existence of a “digital divide” that limits patient access to distance psychological services, such as in rural communities. As we surveyed only practitioners and not recipients of psychological services, we could not determine what factors led to a lack of broadband access. Both financial and geographical constraints may be contributory; people may live in rural areas where broadband access is lacking, or they may not possess financial resources to purchase equipment allowing for the delivery of telepsychological services.

Most providers disagreed or strongly disagreed (72%, n = 2687) that increased documentation requirements detracted from their ability to provide telepsychology, and most (67%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that technological issues such as dropped sessions or patient/client unfamiliarity with the system interfered with their ability to perform telepsychology. Most respondents (67%) did not find that regulatory complexity regarding service provision or reimbursement had a negative effect on their practices. Roughly the same percentage (66%, n = 2676) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that telepsychology had negatively affected their lives because of the absence of an actual office environment with defined office hours, and 61% of respondents believed that their patients were as accepting of telepsychological services as they were of in-person services. This is a notable change from attitudes reported during our first survey in March 2020, when 86% reported that as many as half of their patients did not like telepsychological service provision (Sammons et al., 2020b).

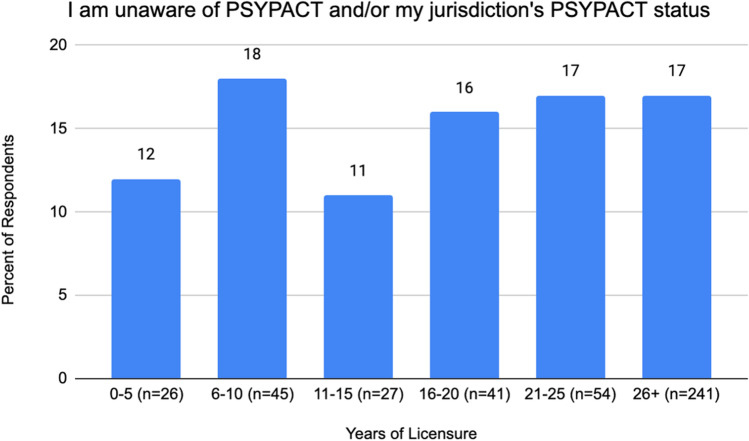

The inter-jurisdictional compact for the practice of psychology (PSYPACT) rapidly expanded during the pandemic. By June 2021, 18 jurisdictions had approved PSYPACT legislation, with legislative action pending in another 8. As of this writing, over 3,300 psychologists had been granted the PSYPACT Authority to Practice Interjurisdictional Psychology (APIT; Janet Pippin Orwig, personal communication, July 9, 2021). Despite the perceived lack of obstacles to telepsychology practice, respondents had decidedly mixed intentions regarding inter-jurisdictional practice, whether via the acquisition of multiple licenses or via PSYPACT (Fig. 7). Only 7% of respondents stated their intention to use telepsychology to expand their practice outside their current licensed jurisdiction (n = 2714). Only 7% stated their intent to become licensed in multiple jurisdictions to practice telepsychology.

Fig. 7.

Psychologists’ Awareness Regarding PSYPACT

Conversely, over one-third (37%) did not intend to practice inter-jurisdictionally. Respondents demonstrated reasonable knowledge regarding PSYPACT, with about one in six respondents unaware of the compact and/or their jurisdiction’s status. Twelve percent of respondents lived in jurisdictions currently members of PSYPACT and have either applied for or received the APIT, and another 15% stated their intent to do so once their jurisdiction became a PSYPACT member.

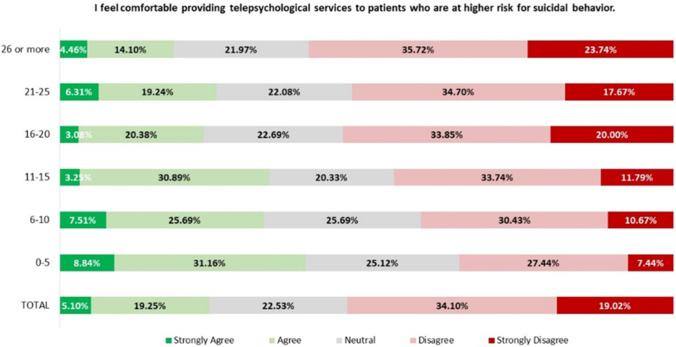

Patients with Suicidal Ideation or Behavior

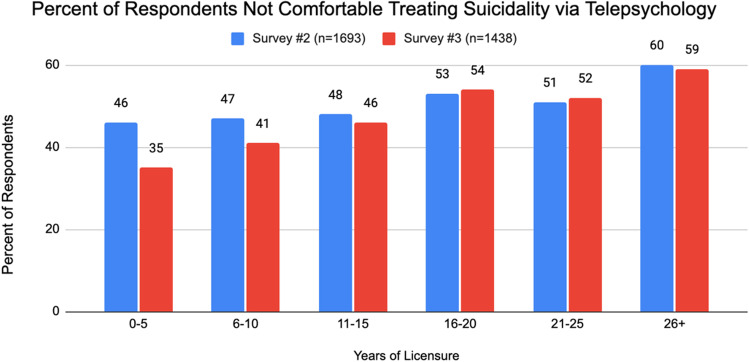

As the pandemic continued, many psychologists maintained discomfort when it came to providing telepsychological services to patients deemed at a higher risk for suicidal behavior. Fifty-three percent (n = 2707) disagreed or strongly disagreed with a survey item stating, “I feel comfortable providing telepsychological services to patients who are at higher risk for suicidal behavior” (Fig. 8). By contrast, 24% of respondents reported they either agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. These results differ from the findings of our September 2020 survey (Fig. 9). Although the samples are not matched, the percentage of psychologists with ten or fewer years of licensure experience who expressed discomfort appeared to drop between the second and third surveys.

Fig. 8.

Comfort with patients at higher risk, June 2021

Fig. 9.

Discomfort with suicidal risk, September 2020 and June 2021

In contrast, this rate remained relatively stable among more experienced practitioners. In the current survey, the observed distribution of respondents who expressed discomfort providing telepsychological services to patients deemed at a higher risk for suicidal behavior was not equal to the expected distribution (χ2(5, n = 1436) = 33.4, p < 0.01). Instead, the observed distribution suggests that a higher percentage of respondents with at least 26 years of licensure experience expressed discomfort than their more early-career colleagues.

Discussion and Implications

Comparisons with Other Surveys

We are aware of only one other large-scale survey of licensed psychologists in the United States that was similar in scope and breadth to ours. In our last report, we noted a similar survey conducted by Pierce et al. (2020); a subsequent re-analysis of these data has recently been published (Pierce et al., 2021). Both of our surveys and that of the Pierce group sampled similar groups of respondents, with respondents to all surveys being more senior clinicians. In our most recent survey, 65% of respondents had been in practice for over 21 years. Pierce et al. (2021) reported a mean number of years of practice at 24.22. Although recruitment methods differed, respondents in both groups of surveys were licensed clinicians, most of whom were in independent or group private practice. Again, though recruitment methods differed, the size of the groups sampled in our surveys was similar, with an average of 3,018 respondents over our three surveys and a total of 2619 in the Pierce et al. (2021) survey. Both groups of respondents reported conducting minimal services via telepsychology before the pandemic. In our recent survey of pre-pandemic services, 67% of respondents provided no telepsychology, and 87% serviced less than 10% of their caseload via telepsychology.

Similarly, respondents to the Pierce et al. (2021) survey performed only 7% of services via telepsychology pre-pandemic. During the pandemic, 87% of our respondents provided telepsychology to at least 90% of their caseload, similar to Pierce et al. with 86% providing services via telepsychology. We did not directly inquire what percentage of caseload our respondents anticipated seeing via telepsychology post-pandemic in the current survey. Still, over half of respondents to all three of our surveys anticipated seeing as much as 50% of their future caseload via telepsychology, while Pierce et al. reported 34%. The similarity of the findings of our three surveys with those of Pierce et al. supports our findings are both robust and durable.

Limitations

Our survey was a convenience sample of psychologists practicing mostly in solo or group private practices who were members of the National Register of Health Service Psychologists or received their professional liability insurance via The Trust. Thus, they may not be representative of all psychologists in the United States. We note, however, that psychologists receiving our survey, by definition, carry an active psychology license and are highly likely to be engaged in direct patient care. We, therefore, believe our sample is likely representative of the opinions of licensed psychologists in active practice.

As noted earlier, we also achieved a response rate to our most recent survey that was lower than that found in our prior two surveys and reported by Pierce et al. (2021). This difference may have resulted from the fact that an email solicitation to participate in the survey was embedded in an email that addressed topics other than the survey. Again, the similarity of the current survey findings to both our previous results and those of external surveys gives us confidence that these results are replicable. In addition, for some analyses missing data were handled via listwise deletion.

Telepsychology may pose some challenges to overall provider satisfaction. Forty-one percent of respondents noted that the growing use of telepsychology made them feel less optimistic about the future of their practice. Although most respondents did not report that telepsychology might negatively affect their lives due to the absence of defined office hours or changing patient expectations, approximately one-third expressed some concern about the negative implications of telepsychology on their professional lives, possibly due to threats to established work-life balance. This result is an area that will require monitoring as telepsychological interventions become embedded into routine practice.

Our survey did not assess any mental health effects on providers who worked with COVID-19 patients. It should be noted that a number of studies of COVID-19 and other recent pandemics have discovered significant short- and long-term mental health implications for providers, particularly front-line providers (Bryant-Genevier et al., 2021; Preti et al., 2020). We must presume that psychologists are among those who can be considered front-line providers in numerous institutions with high COVID-19 patient populations, so we encourage further investigation of the effects on psychologists’ welfare of direct work with victims of the pandemic.

Conclusions

Our survey leads us to unavoidably conclude that telepsychology has become a permanent component of psychological service delivery. We are unable to predict the extent to which both providers and patients will rely on distance versus in-person psychological service provision once in-person options become more convenient. Still, it will most likely be substantially greater than in the past. The risk management aspects of this shift should continue to be monitored. As of this writing, it is too early to conclude that telepsychology has had no effect on provider liability, but this possibility bears future monitoring. Also, while our respondents have embraced telepsychological service provision, with 21% of respondents indicating they intend to provide no in-person services in the future, there remains concern about how this might negatively affect perceptions of psychological practice. These impacts, along with a better understanding of the downstream effects of telepsychological practice on other practice components, including reimbursement rates and work-life flexibility, should remain a focus of a future investigation. We must also note that deciding to provide telepsychology services may aggravate an extant digital divide to the detriment of seekers of psychological services who lack sufficient internet access.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Biographies

Morgan T. Sammons, PhD, ABPP

is the CEO of the National Register of Health Service Psychologists, and the Editor in Chief of the Journal of Health Service Psychology. He is a retired Navy captain and was formerly the U.S. Navy’s specialty leader for clinical psychology.

Daniel M. Elchert, PhD

is a professional consultant at the National Register of Health Service Psychologists. He is a licensed clinical psychologist and statistician who completed his doctoral training at the University of Iowa. Most recently, Dr. Elchert was the Science Policy Fellow at the American Statistical Association and previously completed an APA-accredited predoctoral internship at Michigan State University.

Jana N. Martin, PhD

is the CEO of The Trust. Previously, she was a cochair of the Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists and a coeditor of A Telepsychology Casebook: Using Technology Ethically and Effectively in Your Professional Practice.

References

- Bray MJC, Daneshvari NO, Radhakrishnan I, Cubbage J, Eagle M, Southall P, Nestadt PS. Racial differences in statewide suicide mortality trends in Maryland during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(4):444–447. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Genevier, J., Rao, C. Y., Lopes-Cardozo, B., Kone, L., Rose, C., et al. (2021). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, March–April 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Jun 25 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7026e1.htm?s_cid=mm7026e1_w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- National center for health statistics. (2021). Telemedicine use, household pulse survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/telemedicine-use.htm

- Pierce BS, Perrin PB, McDonald SD. Demographic, organizational, and clinical practice predictors of U.S. psychologists’ use of telepsychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2020;51:184–193. doi: 10.1037/pro0000267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce BS, Perrin PB, Tyler CM, McKee GB, Watson JD. The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in U.S. mental health care delivery. American Psychologist. 2021;76:14–25. doi: 10.1037/amp0000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, Ferrari F, Mazetti M, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers. Rapid Review of the Evidence. 2020;22(8):43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons MT, VandenBos GR, Martin JN, Elchert DM. Psychological practice at six months of COVID-19: A follow-up to the first national survey of psychologists during the pandemic. Journal of Health Service Psychology. 2020;46:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s42843-020-00024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons MT, VandenBos GR, Martin JN. Psychological practice and the COVID-19 crisis: A rapid response survey. Journal of Health Service Psychology. 2020;46:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s42843-020-00013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlizzi, E. P. & Schiller, J. S. (2021). Estimates of mental health symptomatology, by month of interview: United States, 2019. National Center for Health Statistics. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/mental-health-monthly-508.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). Household pulse survey, anxiety and depression. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Volk, J., Palanker, D., O’Brien, M, & Goe, C. L. (2021). States’ actions to expand telemedicine access during COVID-19 and future policy considerations (Commonwealth Fund, June 2021). 10.26099/r95z-bs17.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.