To the Editor,

Smartphone messaging applications (apps) have been used to facilitate communication within medical teams,1 and our anesthesiology practice has used WhatsApp (Facebook, Menlo Park, CA, USA) since July 2018 because it has end-to-end encryption. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way teams communicate, with the banning of in-person gatherings and switch to virtual meetings, and WhatsApp allows asynchronous but up-to-date communication to take place between team members who may be spread across various locations. Anesthesiologists have faced the unique stressors of COVID-19 in a variety of personal and professional ways, and this experience has yet to be quantified. We present a timeline of anonymized messaging app volume and public county COVID-19 case data along with historical context to characterize our group’s pandemic experience. This project was deemed not to meet the definition of research by our institutional review board (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA).

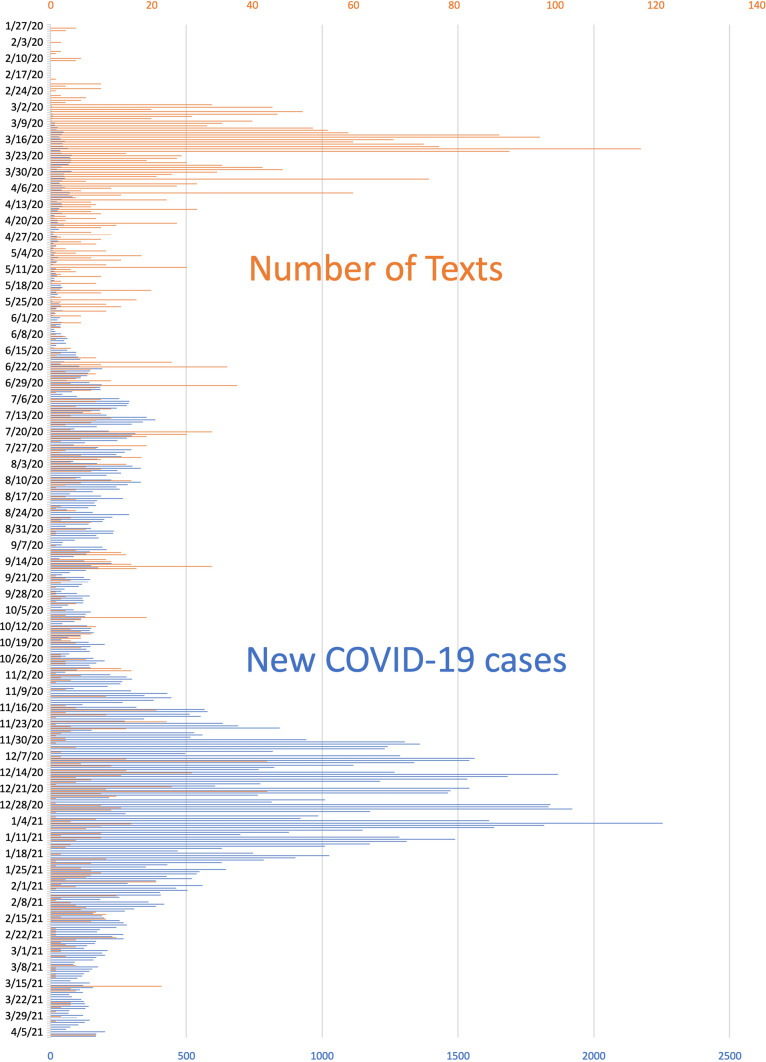

Only 209 messages were sent within our WhatsApp group from July 2018 to January 2020, the month our local county began reporting COVID-19 case volume. Within this interval, the highest daily total was 30 messages. From January 2020 to April 2021, 3,861 WhatsApp messages were exchanged, with 51% sent in the first three months (Figure). This was a busy time of preparation for our group because our first COVID-19 admission was scheduled and publicly announced2 before any local or national guidelines were available. Focusing on clinician and patient safety, we developed personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols using N95 masks, goggles, and Flyte systems (Stryker Corporation, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) designed for orthopedic surgery to ensure head to toe coverage for aerosol-generating procedures.3 By 6 March 2020, five days before the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, 85% of our anesthesiology attendings had already performed donning, doffing, and airway management simulation using this new PPE protocol, and critical care and emergency medicine leaders were added to our WhatsApp group. The highest number of WhatsApp messages per day was 117, which were sent on 21 March 2020, the day after our first COVID-19 intubation. When the American Society of Anesthesiologists issued updated guidance on airway management PPE on 22 March 2020,4 our protocols were already compliant.

Figure.

Number of WhatsApp text messages (orange) and new COVID-19 cases (blue) in Santa Clara County, California from January 2020 to April 2021. COVID-19 case data are publicly available from URL: https://covid19.sccgov.org/dashboard-cases-and-deaths (accessed August 2021).

It is noteworthy that our “surge” of messages occurred in early 2020 when our local county experienced less than 2% of its total COVID-19 cases. We speculate that this volume of messages reflects early activation of a crisis response as well as anxiety and stress at the beginning of the pandemic. Since 9 April 2020, the daily number of WhatsApp messages has not exceeded 50 despite a local county COVID-19 case surge in July 2020, an airway PPE protocol upgrade in December 2020 to the 3M™ Versaflo™ powered air purifying respirator (3M, St. Paul, MN, USA), and a major statewide surge from December 2020 to January 2021 (Figure).

Messaging apps are convenient, available for free, and facilitate critical intra- and interdepartmental communication and information sharing but may be a mixed blessing in terms of employee wellness. Shelter in place orders, social distancing, and school closures due to COVID-19 precluded the hosting of traditional departmental meetings. While messaging apps offer benefits for team communication,1 frequent text messages have been associated with increasing anxiety levels.5 Messaging may also add to after-hours work and hinder work-life integration.

Our timeline of group messaging and county case volume data show an inverse relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that an early decisive crisis response, followed by consistency in processes, helped to alleviate our collective anxiety as shown by the decrease in messaging volume in the months that followed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (Palo Alto, CA, USA). The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Disclosures

None.

Financial statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K.W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ellanti P, Moriarty A, Coughlan F, McCarthy T. The use of WhatsApp smartphone messaging improves communication efficiency within an orthopaedic surgery team. Cureus. 2017 doi: 10.7759/cureus.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kheel R. Veterans Affairs treating one coronavirus patient in California. The Hill 2020 March 4; Available from URL: https://thehill.com/policy/defense/485963-veterans-affairs-treating-one-coronavirus-patient-in-california (accessed August 2021).

- 3.Zamora JE, Murdoch J, Simchison B, Day AG. Contamination: a comparison of 2 personal protective systems. CMAJ. 2006;175:249–254. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UPDATE: The Use of Personal Protective Equipment by Anesthesia Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Society of Anesthesiologists Newsroom 2020 March 22; Available from URL: https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2020/03/update-the-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-by-anesthesia-professionals-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed August 2021.

- 5.Višnjić A, Veličković V, Sokolović D, et al. Relationship between the manner of mobile phone use and depression, anxiety, and stress in university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]