Abstract

A 45-year-old woman presented to us in March 2019 with complaints of fever and right lower quadrant abdominal pain for 1 month. She had undergone renal transplantation in 2017 for end-stage renal disease and developed four episodes of urinary tract infection in the next 16 months post transplantation, which were treated based on culture reports. She was subsequently kept on long-term prophylaxis with trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Her present laboratory parameters showed a normal blood picture and elevated creatinine. Urine culture grew Escherichia coli. Non-contrast CT of the abdomen-pelvis revealed an endo-exophytic hyperdense mass in the graft kidney showing local infiltration and associated few regional lymph nodes. PET-CT revealed the soft-tissue mass and regional lymph nodes to be hypermetabolic, raising the possibility of lymphoma. However, biopsy showed features of malakoplakia. She was subsequently initiated on long-term antibiotic therapy and her immunosuppression decreased.

Keywords: malignant disease and immunosuppression, renal system, urinary and genital tract disorders, renal transplantation, urinary tract infections

Background

Malakoplakia is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory condition presenting as solid masses or soft plaques in various organs.1 It is an uncommon condition resulting from defective macrophage function that has a predilection for the genitourinary tract, but has also been known to affect other organ systems like the gastrointestinal tract, bone, lungs, lymph nodes and skin, with a female predominance.2 The aetiology of this inflammatory condition is not fully known, but it is proposed that it is seen more commonly in patients with immunosuppression, recurrent infections and systemic illnesses.3 We present a case of renal transplant malakoplakia mimicking post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), arising in an immunosuppressed patient in the background of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs). She was managed with a reduction in immunosuppression and long-term antibiotic therapy.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman presented to us in March 2019 with complaints of fever and right lower quadrant abdominal pain for 1 month. She was diagnosed as a case of end-stage renal disease due to chronic glomerulonephritis in September 2016. Subsequently, she was initiated on renal replacement therapy, and after 14 months of hemodialysis, she underwent living related ABO compatible renal transplantation with her husband as the donor on 29 November 2017. She received basiliximab induction (20 mg D0, D4) and was kept on maintenance triple immunosuppressive therapy with tacrolimus, mycophenolate and prednisolone. In the immediate post-transplant period, she had biopsy-proven antibody mediated rejection and was successfully treated with plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin. She was discharged with a serum creatinine of 1.01 mg/dL. During the next 16 months, she developed four episodes of urinary tract infection and was treated based on cultures. Organisms identified during episodes included Klebsiella pneumoniae in two episodes and Escherichia coli in one episode. She was kept on long-term prophylaxis with trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole.

On admission, her blood pressure was 122/84, oxygen saturation of 99% on room air, respiratory rate measuring 20 bpm, temperature of 38.5°C and a pulse rate of 84 bpm. Pertinent physical findings included right iliac fossa tenderness. Laboratory investigations showed a normal blood picture and elevated serum creatinine (1.47 mg/dL). Urine culture grew E. coli. Tacrolimus level was 4.1 ng/mL.

Investigations

An abdominal ultrasound was performed to rule out renal abscess or pyelonephritis, which revealed a well-defined solid hypoechoic mass in the lower pole of the graft kidney with a few enlarged locoregional lymph nodes.

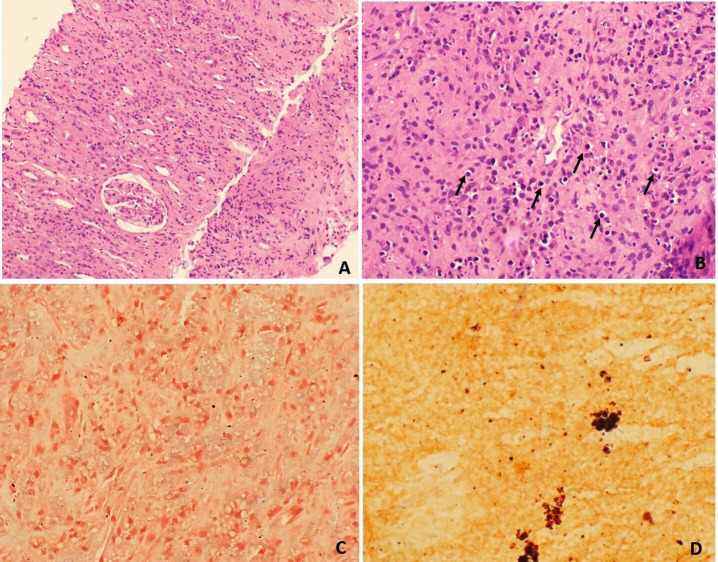

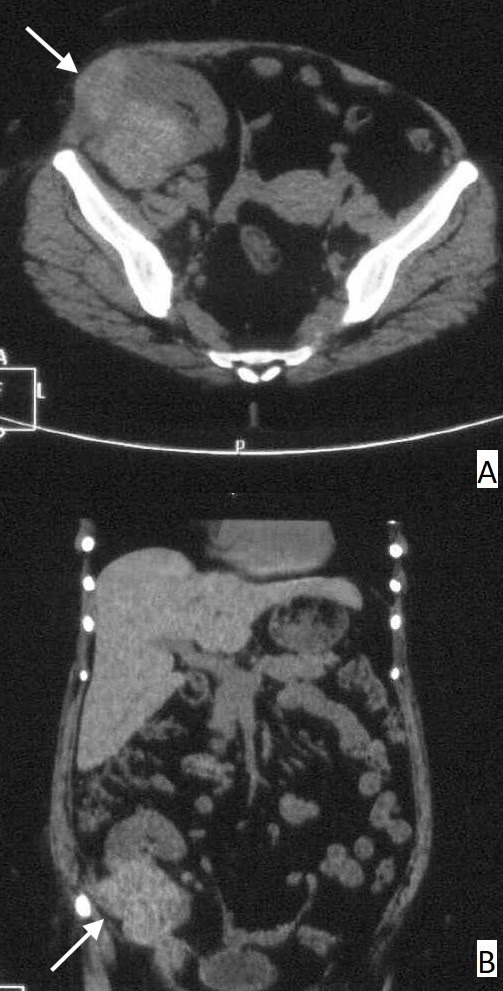

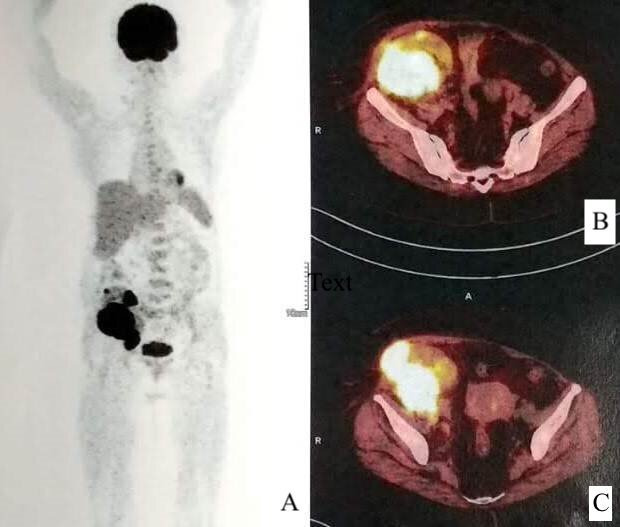

Non-contrast CT of the abdomen-pelvis was done for further characterisation of the mass (contrast not administered due to risk of contrast nephropathy) which showed a well-defined oval hyperdense mass involving the mid and lower pole of the graft kidney measuring 5.7×8.0×11.0 cm (AP×TR×CC) in size. The mass had an exophytic component locally infiltrating the muscles of right anterior abdominal wall in right iliac fossa region and associated few enlarged regional lymph nodes (figure 1). A diagnosis of PTLD was suspected and PET-CT was done, which revealed a hypermetabolic soft-tissue lesion in the graft kidney with local infiltration and regional lymph node involvement, favouring the possibility of PTLD (figure 2). For tissue diagnosis, we did a Ultrasound (USG)-guided core biopsy. On histological examination, the biopsy showed largely unremarkable glomerulus and necrosed interspersed tubules. However, the interstitium showed infiltration by foamy histiocytes (von Hansemann histiocytes), mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous small round partly calcified Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. (figure 3A and B). Special stains for iron (Perls) and calcium (von Kossa) confirmed the nature of these bodies (figure 3C and D). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of malakoplakia, and the patient was diagnosed with renal transplant malakoplakia.

Figure 1.

Non–contrast-enhanced CT scan axial (A) and coronal images (B) showing a large, well-defined, lobulated, partially exophytic hyperdense mass at the mid and lower pole of graft kidney locally infiltrating the muscles of the right anterior abdominal wall (arrows) in the right iliac fossa region and associated few enlarged regional lymph nodes.

Figure 2.

Whole-body PET multiplanar reconstructed image (A) and fused PET-CT axial images (B, C) at the level of graft kidney showing hypermetabolic soft-tissue lesion in the graft kidney with local infiltration.

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph from renal mass biopsy shows (A) largely unremarkable glomeruli and mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium (H&E stain, ×400 magnification), (B) numerous rounded calcified Michaelis-Gutman bodies (arrows) scattered in the interstitium (H&E stain, ×400 magnification), (C) Perl’s stain showing blue staining of iron deposition (Perl’s stain, ×400 magnification) and (D) von Kossa stain showing black staining of calcium deposits (von Kossa stain, ×400 magnification).

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of renal malakoplakia includes local abscess, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, renal cell carcinoma and non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma in transplanted and/or immunocompromised patients.

Making a clinical or radiological diagnosis of malakoplakia can prove difficult due to its somewhat non-specific findings, but the condition should be suspected in cases of renal enlargement or mass in the presence of UTI and/or a history of recurrent UTI, especially in immunocompromised patients. These findings require work-up with renal biopsy.

It is necessary to distinguish malakoplakia from renal tumours or other processes since the work-up and treatment of these entities differ. While the gross presentation of the condition may resemble carcinoma, which indicates nephrectomy, malakoplakia calls for conservative management with medicinal therapy.

Treatment

She was initiated on long-term antibiotic therapy with doxycycline 100 mg twice and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (160/800) three times a day. Her immunosuppression was decreased to wysolone 5 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily, and tacrolimus levels were targeted at 3–5 ng/dL.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made a good recovery. She has been on regular follow-up and her serum creatinine is in the normal range. Follow-up ultrasound revealed a significant reduction in the size of the renal mass and regional lymph nodes. Until now, she has not had any further clinical manifestations of malakoplakia, nor has she presented with any septic episodes or UTI.

Discussion

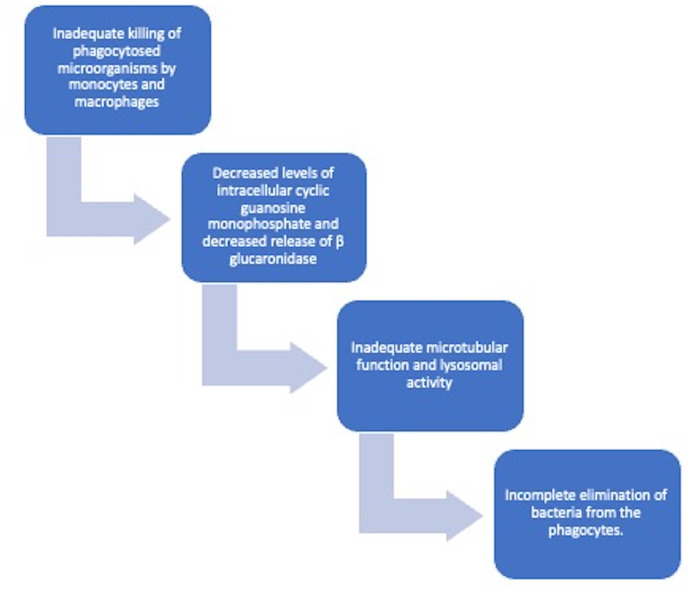

Malakoplakia is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of infectious aetiology. It usually affects the genitourinary tract, although it can affect the gastrointestinal tract and other systems.1 It occurs due to inadequate killing of bacteria by macrophages or monocytes, which show defective phagolysosomal activity2 (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Flowchart depicting pathogenesis of malakoplakia.

Predisposing factors include recurrent infections, systemic illnesses and immunosuppression states like solid organ transplantation, HIV and diabetes.3 It has been increasingly reported after renal transplantation. There are 40 case reports of malakoplakia after renal transplantation; isolated graft malakoplakia has been reported in only 12 of them4–15 (table 1).

Table 1.

Various characteristics of past patients with renal graft malakoplakia

| Authors (Year) |

Age Gender |

Duration of transplant (months) | Immunosuppression | Clinical features | Organism isolated | Management | Outcome |

| Keitel E et al (2014)4 | 23/f | 1 | Tac Mmf Pred |

UTI and graft dysfunction | E. coli | Prolonged antibiotic therapy Taper immunosuppression |

Graft failure |

| Husek K et al (2000)5 | 44/f | NA | Cyc Pred |

UTI Graft dysfunction |

E. coli | Piperacillin Pefloxacin |

Improved |

| Mullan H et al (1978)6 | 42/f | 21 | NA | Recurrent UTI Graft dysfunction Concomitant Aspergillus infection |

E. coli | Nephrectomy | Death |

| El Aouni N et al (2010)7 | 60/m | 60 | NA | UTI Graft dysfunction |

E. coli | NA | NA |

| Honsova E et al (2012)8 | 31/f | 36 | Tac Mmf |

UTI Graft dysfunction |

E. coli | Flouroquinolones Taper immunosuppression |

Improved |

| Barker THW et al (1984)9 | 43/f | 6 | Pred Aza |

Recurrent UTI | E. coli | Postmortem diagnosis | Death due to pericolic abcess septicaemia |

| McKenzie KJ et al (1996)10 | 29/f | 96 | Pred Aza |

Recurrent UTI | E. coli | Prolonged antibiotic therapy | Stable graft function at 3 years of follow-up |

| Pirojsakul K et al (2015)11 | 14/f | 12 | Tac Mmf Pred |

UTI Cystic graft mass |

E. coli | Ceftriaxone Mmf stopped Tac low target |

Improved |

| Pusl T et al (2006)12 | 43/f | 24 | Tac Mmf |

UTI Hypoechoic masses on USG |

E. coli | Prolonged antibiotic therapy | Improved |

| Augusto J-F et al (2008)13 | 56/f | 11 | Tac Mmf |

UTI Graft dysfunction |

E. coli | Levofloxacin for 10 weeks | Improved Salt-losing nephropathy |

| Puerto IM et al (2007)15 | 45/f | 24 | NA | UTI Cysts and cavities on USG |

E. coli | Graft nephrectomy diagnosis | Improved |

| Our patient | 45/f | 17 | Tac Mmf Pred |

Recurrent UTI Graft mass and dysfunction |

E. coli

K. pneumoniae |

Taper immunosuppression Prolonged antibiotic therapy |

Improved |

Aza, azathiophrin; Cyc, cyclosporine; Mmf, mycophenolate mofetil; NA, not available; Pred, prednisolone; Tac, tacrolimus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

The specific risk factors in post-renal transplant as analysed by Nieto-Rios et al include female sex and past rejections that present as recurrent UTI due to coliforms.1 Our patient had all these features. Although we considered malakoplakia as a possibility, enlarged lymph nodes and hypermetabolic state of the renal mass on PET-CT made us consider PTLD in our patient. Our report highlights that this benign tumour can also show hypermetabolism on PET-CT and enlarged lymph nodes, closely mimicking PTLD.

In the past reports of graft malakoplakia, most patients had urinary tract infections with coliform organisms. Our patient also had culture-proven UTI with these organisms in four episodes. Qualman et al demonstrated E. coli intracellularly by immunocytochemical staining in malakoplakia tissue of four patients. The bacteria were present despite antibiotic-induced sterile urine at the time of biopsy.3

Most patients with graft malakoplakia present with fever, flank pain, palpable mass, recurrent UTI and graft dysfunction. Malakoplakia can have varied imaging features, including bulky transplant kidney, cysts, abscess, and graft mass.

In most of the case reports, nuclear scintigraphy was not done. A case report by Melloul et al where Tc-99m dimercapto succinic acid (DMSA) and gallium were done showed that malakoplakia manifests as decreased uptake on DMSA and increased uptake on a gallium scan.14 Our case report is among the few recent reports to describe the PET findings of renal malakoplakia.

In most of the reports done so far, malakoplakia was always a biopsy finding. However, according to the available literature, a diagnosis of malakoplakia must be entertained in a patient, especially women with a background of heavy immunosuppression and recurrent UTI due to coliforms. This will lead to early diagnosis and treatment of patients.

Treatment of malakoplakia is contingent on the extent of the disease and the underlying conditions of the patient. In past reports, patients received different modalities of management, including tapering immunosuppression, long-term antibiotic therapy including quinolones, and surgery. Our patient was managed with tapering of immunosuppression and long-term antibiotic treatment.

Conventional antibiotic therapy fails to clear intracellular organisms. Prolonged antibiotic treatment with trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, rifampin, doxycycline and vancomycin, which have good intracellular penetration, has been used successfully in past reports.3 In addition, a cholinergic agonist, like bethanechol, used in combination with antibiotics, is supposed to improve intracellular Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels and promote intracellular killing of the coliforms.3 Surgical excision is the choice of treatment for extensive unifocal diseases.

In conclusion, malakoplakia is a rare granulomatous condition that can arise in organ transplant recipients and, given the potential for significant morbidity if missed, malakoplakia must be included in the differential diagnosis of renal transplant recipients who present with fever, flank pain, renal mass, and graft dysfunction with or without recurrent UTI. Although imaging studies are helpful for diagnosis, kidney biopsy is still the gold-standard method. Treatment should include long-term antibiotics with a reduction in immunosuppressive medications. Renal transplant nephrectomy must be considered only in refractory cases.

Learning points.

Renal transplant malakoplakia commonly presents with fever, flank pain and/or a palpable mass closely resembling other renal pathologies such as local abscess, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, renal cell carcinoma and lymphoma.

Due to its non-specific findings, making a clinical or radiological diagnosis of malakoplakia can prove difficult, but the condition should be strongly suspected in the presence of UTI and/or a history of recurrent UTI, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Cases with suspicion of malakoplakia should be worked up with renal biopsy as it is essential for the diagnosis of the disease. Differentiation of the condition from other processes is extremely important as the treatment of these entities differs.

Malakoplakia is believed to be due to inadequate killing of bacteria by macrophages or monocytes as a result of defective phagolysosomal activity.

Treatment of malakoplakia is contingent on the extent of the disease, and includes tapering of immunosuppression, long-term antibiotic therapy and surgery.

Footnotes

Contributors: MRJ, VT and SA conducted the study including patient recruitment, data collection and data analysis. VT and SA did the literature review and prepared the manuscript draft. All the authors had complete access to study data. The manuscript was finally reviewed by MRJ and HL.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Nieto-Ríos JF, Ramírez I, Zuluaga-Quintero M, et al. Malakoplakia after kidney transplantation: case report and literature review. Transpl Infect Dis 2017;19. 10.1111/tid.12731. [Epub ahead of print: 12 07 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lou TY, Teplitz C. Malakoplakia: pathogenesis and ultrastructural morphogenesis. A problem of altered macrophage (phagolysosomal) response. Hum Pathol 1974;5:191–207. 10.1016/S0046-8177(74)80066-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qualman SJ, Gupta PK, Mendelsohn G. Intracellular Escherichia coli in urinary malakoplakia: a reservoir of infection and its therapeutic implications. Am J Clin Pathol 1984;81:35–42. 10.1093/ajcp/81.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keitel E, Pêgas KL, do Nascimento Bittar AE, et al. Diffuse parenchymal form of malakoplakia in renal transplant recipient: a case report. Clin Nephrol 2014;81:435–9. 10.5414/CN107506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husek K, Sobotová D. Diagnosis of malacoplakia in a transplanted kidney by needle biopsy. Ceskoslov Patol 2000;36:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullan H, Hesse VE. Malacoplakia of a cadaveric renal allograft: a case report. J Surg Oncol 1978;10:197–200. 10.1002/jso.2930100304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Aouni N, François H, Frangie C, et al. Lésion rénale inhabituelle CheZ un transplanté rénal. Ann Pathol 2010;30:156–8. 10.1016/j.annpat.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honsova E, Lodererova A, Slatinska J, et al. Cured malakoplakia of the renal allograft followed by long-term good function: a case report. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2012;156:180–2. 10.5507/bp.2012.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker TH, Gresham GA. Malakoplakia in a renal allograft. Br J Urol 1984;56:549–50. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1984.tb06282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenzie KJ, More IA. Non-Progressive malakoplakia in a live donor renal allograft. Histopathology 1996;28:274–6. 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirojsakul K, Powell J, Sengupta A, et al. Mass lesions in the transplanted kidney: answers. Pediatr Nephrol 2015;30:1109–11. 10.1007/s00467-014-2788-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pusl T, Weiss M, Hartmann B, et al. Malacoplakia in a renal transplant recipient. Eur J Intern Med 2006;17:133–5. 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Augusto J-F, Sayegh J, Croue A, et al. Renal transplant malakoplakia: case report and review of the literature. NDT Plus 2008;1:340–3. 10.1093/ndtplus/sfn028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melloul MM, Shmueli D, Mechlis-Frish S, et al. Scintigraphic evaluation of parenchymal malakoplakia in a transplanted kidney. Clin Nucl Med 1988;13:525–6. 10.1097/00003072-198807000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puerto IM, Mojarrieta JC, Martinez IB, et al. Renal malakoplakia as a pseudotumoral lesion in a renal transplant patient: a case report. Int J Urol 2007;14:655–7. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]