Abstract

Objectives

This study examines the characteristics and outcomes of child welfare investigations reported by hospital-based and community-based healthcare professionals.

Methods

A sample of 7590 child maltreatment-related investigations from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2018, a cross-sectional study, was analysed. Bivariate analyses compared characteristics of hospital and community healthcare-reported investigations. Chi-square automatic interaction detector analyses were used to predict the most influential factors in the decision to provide a family with services following a child welfare investigation from each referral source.

Results

Community healthcare-reported investigations were more likely to have a primary concern of physical abuse while hospital-reported investigations were more likely to be focused on assessing risk of future maltreatment. Hospital-reported investigations were more likely to involve noted primary caregiver (eg, mental health issues, alcohol/drug abuse, victim of intimate partner violence (IPV)) and household risk factors. The most significant predictor of service provision following an investigation was having a caregiver who was identified as a victim of IPV in hospital-reported investigations (χ2=30.237, df=1, adj. p<0.001) and having a caregiver for whom few social supports was noted in community healthcare-reported investigations (χ2=18.892, df=1, adj. p<0.001).

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals likely interact with children who are at high risk for maltreatment. This study’s findings highlight the important role that healthcare professionals play in child maltreatment identification, which may differ across hospital-based and community-based settings and has implications for future collaborations between the healthcare and child welfare systems.

Keywords: child abuse, social work

What is known about the subject?

Child maltreatment can have detrimental effects on health.

Healthcare professionals play an important role in identifying and reporting child maltreatment.

Healthcare professionals in hospital-based settings are more likely to report younger children (under 3 years old) to child welfare agencies.

What this study adds?

Investigations reported by hospital-based providers are more likely to focus on assessing risk of future maltreatment and involve primary caregiver and household risk factors.

Investigations reported by community-based healthcare professionals are more likely to involve a primary concern of physical abuse.

Families reported by healthcare professionals are more likely to receive services following an initial investigation if they involve noted primary caregiver risk factors.

Introduction

Child maltreatment has detrimental effects on child health.1 2 Healthcare professionals, as mandatory reporters, are one of the best-positioned groups to identify child maltreatment.3 This is true across various divisions of the healthcare system, while primary care providers are in frequent and continuous contact with families and may notice the initial signs of maltreatment, hospital-based providers may encounter more severe cases of abuse or neglect.4–6 Healthcare professionals make up approximately 10% of reports to child welfare services in Canada and play an important role in protecting vulnerable populations such as infants and young children,4 7 8 children with disabilities,8 9 and children with physical and mental health conditions.8 Further, investigations reported to child welfare by healthcare professionals are more likely to be substantiated than reports from non-professional sources (eg, relatives, community members).10

Existing literature has explored the characteristics of investigations reported to child welfare by hospital-based providers, including emergency department physicians. Within the Canadian context, an analysis of data from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2013 (OIS-2013) revealed that investigations reported by hospital-based providers most often involved concerns for children at risk of future maltreatment, followed by concerns of exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV), neglect and physical abuse.7 Investigations that assess whether a child is at risk of future maltreatment are not focused on alleged maltreatment but rather on assessing if risk factors in the child’s environment may lead to future maltreatment, including concerns about the caregiver.11 Hospital-based reports are often initiated because caregivers require acute care for medical needs related to domestic violence, substance abuse or a mental health crisis.12 13 Studies examining maltreatment concerns originating from emergency departments in the USA show high rates of physical abuse and neglect, likely due to severe injury presentation.14 15 In both the USA and Canada, young children, particularly infants, are more likely to be hospitalised due to severe maltreatment-related injuries.15–18

Most studies that have examined child welfare reports from community-based healthcare professionals focus on their attitudes towards and experiences with mandatory reporting.6 19–21 One study investigating reports to child welfare from a paediatric clinic found that child developmental concerns, maternal drug use and maternal depression were the most likely predictors in the decision to report.22

The OIS-2018 presents an opportunity to understand the characteristics and outcomes of investigations reported to Ontario child welfare by the healthcare system. In Ontario, every citizen has a duty to report child maltreatment to child welfare; healthcare providers are particularly responsible as failure to do so may result in a fine.23 Reports are screened by the local child welfare agency to determine whether they meet the criteria to be opened for an investigation. Mandated child welfare agencies in Ontario operate under a decentralised model, but all are governed by provincial child protection legislation, the Child, Youth and Family Services Act.11

This paper uses data from the OIS-2018 to (1) compare characteristics and service outcomes in hospital and community healthcare-reported investigations (see table 1 for variable definitions) and (2) identify the family and case characteristics that predict the decision to provide families with services (ie, ongoing child welfare services or a referral to services external to child welfare) following an initial child welfare investigation reported by hospital-based and community-based healthcare workers.

Table 1.

Variable definitions

| Variable | Definition |

| Hospital report | Refers to investigations where the source of the report works in a hospital-based setting, such as physicians, nurses and social workers. |

| Community healthcare report | Refers to investigations where the source of the report is a community-based healthcare professional, including physicians and nurses. |

| Household income | Refers to the caregiver’s primary source of income, including full-time, part-time or seasonal employment, as well as insurance and other benefits. |

| Number of moves | Refers to the number of times the household has moved in the past year. |

| Home overcrowding | Refers to whether the house is overcrowded, based on the opinion of the investigating worker. |

| Unsafe housing conditions | Refers to instances where a worker deemed housing conditions unsafe during the investigation, due to mould, inadequate heating, drug paraphernalia, etc. |

| Child age | Refers to the age of the child(ren) living in the home at the time of the investigation. |

| Ran out of money in the past 6 months | Refers to investigations where the household ran out of money for basic necessities in the past 6 months (ie, food, housing, utilities, telephone/cell phone, transportation). |

| Primary caregiver risk factors | Refers to investigations where workers have indicated that the primary caregiver has a risk factor(s) (ie, alcohol abuse, drug/solvent abuse, cognitive impairment, mental health issues, physical health issues, few social supports, victim of IPV, perpetrator of IPV, history of foster care/group homes, at least one functioning issue). |

| At least one child functioning concern | Refers to investigations where workers have identified at least one child functioning concern (ie, positive toxicology at birth, FASD, failure to meet developmental milestones, intellectual/developmental disabilities, attachment issues, ADHD, aggression/conduct issues, physical disability, academic/learning difficulties, depression/anxiety/withdrawal, self-harming behaviour, suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, inappropriate sexual behaviour, running (multiple incidents), alcohol abuse, drug/solvent abuse, Youth Criminal Justice Act or other.) |

| Primary concern of investigation | Refers to the primary risk or maltreatment concern identified by the worker, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, exposure to IPV, neglect or risk of future maltreatment |

| Substantiation | Refers to investigations where the investigating worker concluded, based on available evidence, that the child was a victim of maltreatment. |

| Physical harm | Refers to investigations where there was evidence that a child was physically harmed (ie, bruises, cuts, scrapes, broken bones, burns, head trauma, fatal or health condition). |

| Significant risk of future maltreatment | Refers to investigations where workers believed there to be a significant risk that a child would suffer future maltreatment. |

| Service referral made | The family received a service referral following the initial investigation, either internal or external to the child welfare agency (ie, parent education or support services, family or parent counselling, drug/alcohol counselling or treatment, psychiatric/mental health services, intimate partner violence services, welfare or social assistance, food bank, shelter services, housing, legal, child victim support services, special education placement, recreational services, medical or dental services, speech/language, child or day care, cultural services, immigration services or other). |

| Transfer to ongoing services | Refers to instances where, following the initial investigation, a worker opted to keep the case open and transfer it to ongoing services. |

| Placement during investigation | Refers to instances where a child was placed in out of home care during the investigation. |

| Case closed with no additional services provided | Following the initial investigation, no family members received a referral to services external to child welfare and the case was not transferred to ongoing services. |

ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; FASD, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder; IPV, intimate partner violence.

Methods

We conducted secondary analyses of data from the OIS-2018, the sixth cycle of a study that examines the incidence rates and characteristics of child welfare investigations in Ontario.24 Using a standardised online data collection instrument, investigating workers provide information on child, family, and case characteristics, and short-term service dispositions. This includes an investigation’s referral source, with categories for reports from hospitals (such as physicians, nurses and social workers), and community health physicians and nurses (referred to herein as ‘community healthcare reports’). Both the completion rate and the participation rate for the 2018 cycle were over 99%.11

The OIS-2018 used a multistage sampling design. In the first stage, 18 child welfare agencies were selected from a sampling frame of 48 agencies using stratified random sampling. In the second stage, cases opened at selected agencies between 1 October 2018 and 31 December 2018 were included. Case information in Ontario is collected at the family level, so in the final stage the investigating worker identified children (under the age of 18) investigated for maltreatment-related concerns. The final sample, which included 7590 child maltreatment-related investigations, was weighted to derive estimates of investigation rates for the province. See Fallon et al24 for a description of the weighting procedures.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to determine the incidence rate of investigations with a hospital or community healthcare referral source. The rate per 1000 children was calculated by dividing the weighted estimate by the total child population of Ontario and multiplying by 1000. Bivariate analyses were conducted using χ2 tests to examine the differences between hospital and community healthcare reports across variables including: maltreatment concern, physical harm, child age, presence of at least one child functioning concern, primary caregiver risk factors, household risk factors and case dispositions. The case dispositions captured in the OIS-2018 are not mutually exclusive. See table 1 for a description of the variables used in this analysis.

Chi-square automatic interaction detector (CHAID) analysis was then conducted to identify the factors that predict the decision to provide the family with services beyond the initial child welfare investigation (ie, transfer to ongoing services or make a referral to a non-child welfare service; see table 1). Two CHAIDs were performed, one for hospital reports and one for community healthcare reports. CHAID is an exploratory, multivariate analysis technique where predictor variables are split into categories using χ2 tests.25 All variables start in the root node which is then split to maximise the difference in the dependent variable. The splitting of the tree continues until the terminal node is reached.25 26 To avoid overfitting the data, the minimum sizes for parent (n=50) and child (n=20) nodes were chosen to halt tree growth.27 The predictor variables used in the two CHAIDs were: maltreatment type, child age, physical harm, presence of at least one child functioning concern, the household running out of money in the last six months for basic necessities, as well as primary caregiver risk factors (alcohol abuse, drug/solvent abuse, mental health issues, few social supports, victim of IPV) noted by the investigating worker. All analyses were conducted in SPSS V.27.0.

Patient and public involvement

As the OIS collects data from investigating workers, the children and families investigated are not directly involved in the study design, data collection or reporting processes. Following the completion of each cycle, a report including the study’s major findings is made available to the public.

Results

In the OIS-2018 sample, 441 and 162 investigations were reported by hospital-based and community-based healthcare providers between October and December 2018, respectively. The remaining 6987 reports were made by other professional (eg, schools, police) and non-professional sources (eg, relatives, neighbours). The estimated incidence rates were 3.76 investigations reported by hospital-based providers and 1.40 investigations reported by community-based healthcare providers per 1000 children in Ontario (table 2).

Table 2.

Investigations reported by hospital-based and community-based healthcare professionals in Ontario in 2018

| Estimate | Rate per 1000 | % | |

| Hospital reports | 8884 | 3.76 | 6 |

| Community healthcare reports | 3311 | 1.40 | 2 |

| Other reports | 146 282 | 61.93 | 92 |

| Total reports | 158 477 | 67.10 | 100 |

| Based on a sample of 7590 child maltreatment-related investigations. | |||

Table 3 presents the results of the bivariate analyses which compared investigations reported from hospital and community healthcare sources. Investigations reported by community-based healthcare providers were significantly more likely to involve a physical abuse concern than those reported by hospital-based providers (23% vs 7%). Investigations with a hospital referral source were significantly more likely to be initiated due to concerns of risk of future maltreatment (59% vs 36%). Hospital-reported investigations were significantly more likely to have noted physical harm to the child (15% vs 9%).

Table 3.

Bivariate analyses for investigations reported by hospital and community healthcare sources

| Characteristics | Hospital report | Community healthcare report | χ2 p value | ||

| # | % | # | % | ||

| Household income source | <0.001 | ||||

| Full time | 3995 | 45 | 1628 | 49 | |

| Part time/seasonal | 1206 | 14 | 462 | 14 | |

| Other benefits/unemployment | 2886 | 33 | 826 | 25 | |

| Unknown | 281 | 3 | 153 | 5 | |

| No source of income | 516 | 6 | 228 | 7 | |

| Number of moves | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 4525 | 51 | 1974 | 60 | |

| 1 | 1764 | 20 | 445 | 14 | |

| 2+ | 757 | 9 | 71 | 2 | |

| Unknown | 1838 | 21 | 808 | 25 | |

| Home overcrowding | |||||

| Yes | 1036 | 12 | 211 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Unsafe housing conditions | |||||

| Yes | 419 | 5 | 55 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Ran out of money in the past 6 months for basic necessities | |||||

| Yes | 819 | 9 | 323 | 10 | 0.365 |

| Primary caregiver risk factors | |||||

| Alcohol abuse | 1008 | 11 | 224 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Drug/solvent abuse | 1697 | 19 | 331 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive impairment | 520 | 6 | 203 | 6 | 0.543 |

| Mental health issues | 3665 | 41 | 1252 | 38 | 0.001 |

| Physical health issues | 603 | 7 | 356 | 11 | <0.001 |

| Few social supports | 2834 | 32 | 1094 | 33 | 0.203 |

| Victim of IPV | 2572 | 29 | 719 | 22 | <0.001 |

| Perpetrator of IPV | 484 | 6 | 200 | 6 | 0.196 |

| History of foster care/group home | 754 | 9 | 168 | 5 | <0.001 |

| At least one functioning issue | 6052 | 68 | 2302 | 70 | 0.096 |

| Child age | <0.001 | ||||

| <1 year | 2032 | 23 | 389 | 12 | |

| 1–3 years | 1651 | 19 | 473 | 14 | |

| 4–7 years | 1515 | 17 | 572 | 17 | |

| 8–11 years | 1337 | 15 | 941 | 28 | |

| 12–17 years | 2349 | 26 | 936 | 27 | |

| At least one child functioning concern | |||||

| Yes | 3579 | 40 | 1171 | 35 | <0.001 |

| Primary concern of investigation | <0.001 | ||||

| Physical abuse | 631 | 7 | 774 | 23 | |

| Sexual abuse | 185 | 2 | 84 | 3 | |

| Neglect | 1389 | 16 | 530 | 16 | |

| Emotional maltreatment | 303 | 3 | 147 | 4 | |

| Exposure to IPV | 1101 | 12 | 598 | 18 | |

| Risk | 5275 | 59 | 1179 | 36 | |

| Substantiation | <0.001 | ||||

| Unfounded | 1419 | 39 | 1020 | 48 | |

| Suspected | 300 | 8 | 67 | 3 | |

| Substantiated | 1890 | 52 | 1045 | 49 | |

| Physical harm | |||||

| Yes | 522 | 15 | 190 | 9 | <0.001 |

| Significant risk of future maltreatment | |||||

| Yes | 2664 | 30 | 756 | 23 | <0.001 |

| Service referral made | |||||

| Yes | 4201 | 47 | 1127 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Transfer to ongoing services | |||||

| Yes | 3216 | 36 | 847 | 26 | <0.001 |

| Placement during investigation | |||||

| Yes | 914 | 10 | 61 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Case closed with no additional services | |||||

| Yes | 3661 | 41 | 2000 | 60 | <0.001 |

IPV, intimate partner violence.

Hospital-reported investigations were also significantly more likely to involve caregivers who received benefits as their primary source of income or were unemployed (33% vs 25%), households that had moved in the past year (29% vs 16%), and families who lived in homes that the worker indicated were overcrowded (12% vs 7%) or unsafe (5% vs 2%).

Children involved in investigations reported by hospital-based providers were significantly more likely to be infants or toddlers (ages 0–3; 42% vs 26%). Primary caregivers involved in investigations with a hospital referral source were significantly more likely to have noted alcohol abuse (11% vs 7%), drug/solvent abuse (19% vs 10%), mental health issues (41% vs 38%), be a victim of IPV (29% vs 22%) or have a history of being in foster care or group homes (9% vs 5%). At least one primary caregiver risk factor was noted in approximately 70% of investigations reported by both sources.

Approximately half of the investigations reported by both hospital and community healthcare sources were substantiated. Investigations reported by hospital sources were more likely to result in all short-term service dispositions included in the analysis.

Figure 1 shows the results of the first CHAID, which selected the factors that predict the decision to provide the family with services following an initial child welfare investigation reported by a hospital source. The most significant predictor was that the primary caregiver was noted by the investigating worker to be a victim of IPV (χ2=30.237, df=1, adj. p<0.001), with investigations where this was a concern being significantly more likely to result in further services than investigations where this was not noted (83% vs 54%). Investigations where a caregiver was identified as both a victim of IPV and had noted drug abuse concerns were the most likely to receive services, with 95% of this subsample being transferred to ongoing services or provided with a service referral.

Figure 1.

Provision of ongoing services or a service referral in child maltreatment-related investigations reported by a hospital-based healthcare provider. IPV, intimate partner violence. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

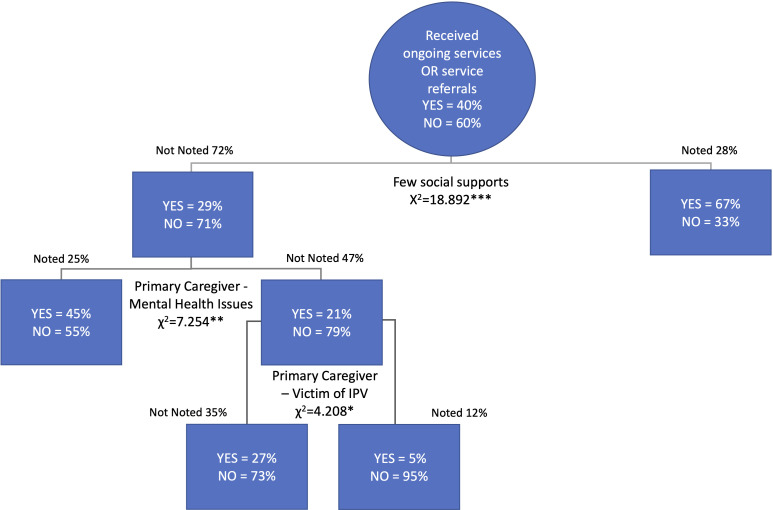

Figure 2 shows the results of the second CHAID, which selected the factors that predict the decision to provide services following an initial child welfare investigation reported by a community healthcare source. The most significant predictor of receiving ongoing services or a service referral in these cases was few social supports being noted as a concern for the primary caregiver (χ2=18.892, df=1, adj. p<0.001). When few social supports was noted as a concern, 67% of investigations involved either a transfer to ongoing services or a referral to a non-child welfare service.

Figure 2.

Provision of ongoing services or a service referral in child maltreatment-related investigations reported by a community-based healthcare provider. IPV, intimate partner violence. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Discussion

This study compares the characteristics and outcomes of investigations reported to child welfare by hospital-based and community-based healthcare providers in Ontario, Canada. The results show that healthcare professionals make up 8% of reports in Ontario, illustrating their vital role in identifying families in need of support and protecting children who seem to be at an especially high risk for maltreatment. This is also evident by the large proportion, approximately 50%, of hospital and community healthcare-reported investigations that were substantiated. This is double the percentage of total investigations that were substantiated in the OIS-2018.24 This could be attributable to multiple factors including that healthcare professionals can provide medical documentation to support maltreatment allegations,10 may see more severe and obvious forms of maltreatment,8 15 28 and as trained medical professionals, are familiar with typical and atypical injury presentations in children.29 30

The findings of this study reveal the distinctive characteristics of the families reported to child welfare who are served in different healthcare settings. Hospital-reported investigations were significantly more likely to have a primary investigation concern of future risk of maltreatment, likely due to the presence of multiple risk factors across different domains (ie, primary caregiver and household factors), in addition to the crisis that led them to seek acute care.7 26 31 The higher percentage of hospital-reported investigations that involved infants also likely contributed to the larger proportion of risk investigations reported by hospitals.26 The results of the CHAID analysis show that the decision to provide hospital-reported families with additional supports was largely driven by having a primary caregiver who was identified as a victim of IPV and had noted drug/solvent abuse. Caregivers who are victims of IPV or have substance use concerns have been shown to have higher rates of hospitalisation and decreased access of ambulatory care, as have caregivers who experience housing instability.32–34 It is possible that families reported to child welfare by hospital-based providers may only come into contact with the healthcare system when they are experiencing an acute crisis (eg, mental health crisis, childbirth, overdose.).

Unlike families reported to child welfare from hospital settings, families who are reported by community-based healthcare professionals may not be in overt or acute physical or psychological distress due to the ambulatory and preventive nature of these services. The finding that community-based healthcare professionals were more likely to report investigations with concerns of physical abuse was unexpected, given the established pattern of hospitalisations due to physical abuse-related injuries in American literature.15 However, studies have shown that paediatricians and primary care physicians are more comfortable reporting cases with injuries indicative of physical abuse than other types of maltreatment, which may contribute to the high proportion of physical abuse concerns.4 29 As community-based healthcare providers assess children on a routine basis, they are well positioned to identify sentinel injuries (relatively minor injuries such as bruises) that may raise concerns of child maltreatment and allow for early intervention.35 The CHAID analysis showed that the primary reason families reported by community-based healthcare professionals received services following an investigation was due to the primary caregiver’s lack of social supports. As healthcare is universally available in Canada, their community-based healthcare provider is likely one of the few, if only, supports an isolated family can access. This positions community-based healthcare providers well to intervene and help establish additional supports for these families.

Following an initial child welfare investigation, hospital-reported families were significantly more likely to receive services than those reported by community-based healthcare professionals. As families who are reported by hospitals may be experiencing an acute crisis and require immediate support, it is possible that their needs are prioritised in a child welfare setting over families reported by community healthcare sources.

The OIS-2018 is a cross-sectional study of child welfare investigations and so the data are unable to support causal assumptions or track the long-term outcomes of the families investigated. The OIS only includes cases reported to and investigated by the child welfare system; cases that are unreported or screened out are not included. The child and caregiver risk factors are based on the clinical judgement of the investigating worker and not diagnosed by a clinician. It is important to note that the weighting only corrects for seasonal fluctuations in investigation volume, and not for the type of investigation when determining annual estimates.

The findings of this study show that healthcare professionals in hospital-based and community-based settings see a specific subset of higher-risk children and that investigations from these sources often involve caregivers with many identified risk factors. This information will help healthcare professionals support their patients including making a report to child welfare when they suspect maltreatment. Further, the findings can help child welfare workers develop informed responses to reports from healthcare sources. This will facilitate improved collaboration between the Ontario healthcare and child welfare systems to support families.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BF conceptualised and supervised the paper. EL synthesised the literature. EL and NJ-C conducted data analyses, data interpretation and wrote the manuscript with assistance from MK-C and DG. BF, DML, AV and JS contributed to data interpretation. All authors had input into the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Canada Research Chair in Child Welfare (#950-231186). Funding for the Ontario Incidence Study was provided by the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Two of the authors have disclosed that they have received payment in the past 36 months for providing expert testimony regarding child maltreatment.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The dataset used and analysed during the current study may be made available in collaboration with BF, study coauthor and the principal investigator of the OIS-2018, on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The OIS received ethics approval from the University of Toronto (protocol #28580).

References

- 1.Kerker BD, Zhang J, Nadeem E, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health, chronic medical conditions, and development in young children. Acad Pediatr 2015;15:510–7. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeb RT, Lewis T, Zolotor AJ. A review of physical and mental health consequences of child abuse and neglect and implications for practice. Am J Lifestyle Med 2011;5:454–68. 10.1177/1559827611410266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKenzie K, Scott DA. Using routinely collected hospital data for child maltreatment surveillance: issues, methods and patterns. BMC Public Health 2011;11:7. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane WG, Dubowitz H. Primary care pediatricians' experience, comfort and competence in the evaluation and management of child maltreatment: do we need child abuse experts? Child Abuse Negl 2009;33:76–83. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karatekin C, Almy B, Mason SM, et al. Health-Care utilization patterns of Maltreated youth. J Pediatr Psychol 2018;43:654–65. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nouman H, Alfandari R, Enosh G, et al. Mandatory reporting between legal requirements and personal interpretations: community healthcare professionals' reporting of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 2020;101:104261. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallon B, Filippelli J, Joh-Carnella N, et al. Trends in investigations of abuse or neglect referred by hospital personnel in Ontario. BMJ Paediatr Open 2019;3:e000386. 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tonmyr L, Li YA, Williams G, et al. Patterns of reporting by health care and nonhealth care professionals to child protection services in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2010;15:e25–32. 10.1093/pch/15.8.e25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karni-Visel Y, Hershkowitz I, Hershkowitz F, et al. Increased risk for child maltreatment in those with developmental disability: a primary health care perspective from Israel. Res Dev Disabil 2020;106:103763. 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King B, Lawson J, Putnam-Hornstein E. Examining the evidence: reporter identity, allegation type, and sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of maltreatment substantiation. Child Maltreat 2013;18:232–44. 10.1177/1077559513508001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallon B, Lefebvre R, Filippelli J, et al. Major findings from the Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect 2018. Child Abuse Negl 2021;111:104778. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rachamim E, Hodes D, Gilbert R, et al. Pattern of hospital referrals of children at risk of maltreatment. Emerg Med J 2011;28:952–4. 10.1136/emj.2009.080176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diderich HM, Fekkes M, Verkerk PH, et al. A new protocol for screening adults presenting with their own medical problems at the emergency department to identify children at high risk for maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 2013;37:1122–31. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keshavarz R, Kawashima R, Low C. Child abuse and neglect presentations to a pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Med 2002;23:341–5. 10.1016/S0736-4679(02)00575-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King AJ, Farst KJ, Jaeger MW, et al. Maltreatment-Related emergency department visits among children 0 to 3 years old in the United States. Child Maltreat 2015;20:151–61. 10.1177/1077559514567176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett S, Ward M, Moreau K, et al. Head injury secondary to suspected child maltreatment: results of a prospective Canadian national surveillance program. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35:930–6. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farst K, Ambadwar PB, King AJ, et al. Trends in hospitalization rates and severity of injuries from abuse in young children, 1997-2009. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1796–802. 10.1542/peds.2012-1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montgomery V, Trocmé N. Injuries caused by child abuse and neglect. CECW Information Sheet #10E. Toronto, ON, Canada: Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster RH, Olson-Dorff D, Reiland HM, et al. Commitment, confidence, and concerns: assessing health care professionals' child maltreatment reporting attitudes. Child Abuse Negl 2017;67:54–63. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McTavish JR, Kimber M, Devries K, et al. Mandated reporters' experiences with reporting child maltreatment: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013942. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nouman H, Alfandari R. Identifying children suspected for maltreatment: the assessment process taken by healthcare professionals working in community healthcare services. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020;113:104964. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubowitz H, Kim J, Black MM, et al. Identifying children at high risk for a child maltreatment report. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35:96–104. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Child, youth and family services act S.O., C.14, sched 1, 2017. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17c14 [Accessed July 22, 2021].

- 24.Fallon B, Filippelli J, Lefebvre R, et al. Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and Neglect-2018 (OIS-2018). Toronto, ON: Child Welfare Research Portal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kass GV. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. Appl Stat 1980;29:119–27. 10.2307/2986296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filippelli J, Fallon B, Trocmé N, et al. Infants and the decision to provide ongoing child welfare services. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2017;11:24. 10.1186/s13034-017-0162-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glăvan IR PD, Simion E. CART versus CHAID behavioural biometric parameter segmentation analysis. In: Bica I, Naccache D, Simion E, eds. Innovative security solutions for information technology and communications. SECITC 2015. Lecture notes in computer science. Cham: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trocmé N, MacMillan H, Fallon B, et al. Nature and severity of physical harm caused by child abuse and neglect: results from the Canadian incidence study. CMAJ 2003;169:911–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuruppu J, McKibbin G, Humphreys C, et al. Tipping the scales: factors influencing the decision to report child maltreatment in primary care. Trauma Violence Abuse 2020;21:427–38. 10.1177/1524838020915581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnitzer PG, Slusher PL, Kruse RL, et al. Identification of ICD codes suggestive of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35:3–17. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon JD, Brooks D. Identifying families with complex needs after an initial child abuse investigation: a comparison of demographics and needs related to domestic violence, mental health, and substance use. Child Abuse Negl 2017;67:294–304. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kothari CL, Rohs T, Davidson S, et al. Emergency department visits and injury hospitalizations for female and male victims and perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Advances in Emergency Medicine 2015;2015:1–11. 10.1155/2015/502703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, et al. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:71–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.French MT, McGeary KA, Chitwood DD, et al. Chronic illicit drug use, health services utilization and the cost of medical care. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1703–13. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00411-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christian CW. Committee on child abuse and neglect, American Academy of pediatrics. the evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1337–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The dataset used and analysed during the current study may be made available in collaboration with BF, study coauthor and the principal investigator of the OIS-2018, on reasonable request.