Abstract

Pterins are one of the major sources of bright coloration in animals. They are produced endogenously, participate in vital physiological processes and serve a variety of signalling functions. Despite their ubiquity in nature, pterin-based pigmentation has received little attention when compared to other major pigment classes. Here, we summarize major aspects relating to pterin pigmentation in animals, from its long history of research to recent genomic studies on the molecular mechanisms underlying its evolution. We argue that pterins have intermediate characteristics (endogenously produced, typically bright) between two well-studied pigment types, melanins (endogenously produced, typically cryptic) and carotenoids (dietary uptake, typically bright), providing unique opportunities to address general questions about the biology of coloration, from the mechanisms that determine how different types of pigmentation evolve to discussions on honest signalling hypotheses. Crucial gaps persist in our knowledge on the molecular basis underlying the production and deposition of pterins. We thus highlight the need for functional studies on systems amenable for laboratory manipulation, but also on systems that exhibit natural variation in pterin pigmentation. The wealth of potential model species, coupled with recent technological and analytical advances, make this a promising time to advance research on pterin-based pigmentation in animals.

Keywords: animal coloration, visual signalling, pleiotropy, ornamentation, sexual selection, aposematism

1. Introduction

Colour is a vital component of the biology of many animals. Through different colourful hues and patterns, animals generate complex phenotypes that mediate their relationship with members of their own species and other elements of the biotic community, as well as their response to specific abiotic features of their ecosystems [1]. Traits associated with the expression of colourful and cryptic displays are vital components of individual fitness, so are thus prime targets for natural and sexual selection. Owing to the relative ease by which colour can be assessed and quantified compared to other traits, the biology of coloration has been extensively studied within the context of animal behaviour, ecology, genetics, developmental biology and evolutionary biology [1]. It also provides easily understandable examples that can improve scientific understanding of evolutionary principles and concepts in biology among the general public.

Colour production can be either pigmentary or structural. Pigmentary colours originate from compounds that exhibit selective absorption of specific wavelengths of light, allowing light of other wavelengths to be reflected. Structural coloration encompasses several phenomena by which colour is generated by the interactions between incident light and an ordered or quasi-ordered nanostructured tissue, leading to constructive or destructive interference for different wavelengths of light. Pigmentary and structural mechanisms often interact to increase display complexity [2,3]. Colour generation by pigments has been extensively studied at multiple levels, and several integumentary pigment classes have been described, the most common of which include melanins, carotenoids, pterins and ommochromes. Despite their biological importance, these have received unequal attention by biologists. For example, the predominant use of mammalian and bird models, whose pigmentation is largely the result of melanins [4–6] and/or carotenoids [7–9], has hampered our understanding of the evolution of colour to the detriment of other pigmentation types. Pterin pigmentation in particular has been the focus of comparatively fewer studies, and basic gaps persist in our knowledge.

The study of pterins had its genesis in research carried out on butterfly wing coloration. They were first isolated and characterized by Hopkins [10–12] and Griffiths [13], who ascribed a variety of mostly white and yellow pigments isolated from pierid butterflies (figure 1a,b) to uric acid or its derivatives, and called them ‘lepidotic acid’ (referencing butterflies, Lepidoptera). The interpretation at the time was that these animals were using excretory substances in ornamentation. Their classification as derivatives of uric acid was afterwards disputed by Schöpf & Wieland [14,15], who noted similarities but also important differences in their chemical properties. These authors termed the pigments ‘pterin’, from the Greek ‘πτερόν’ (pterón—‘feather, wing’), calling the yellow pigment xanthopterin and the white pigment leucopterin, reflecting their optical properties. The chemical structure of these pigments, composed of a pteridine ring system, was later determined by the work of Purrmann [16,17], Wieland & Decker [16–18]. Knowledge on the diversity of pterins was further expanded by the identification of other similar pigments in subsequent years [19], such as isoxanthopterin, erythropterin, pterorhodin, drosopterin and isodrosopterin (figure 2a).

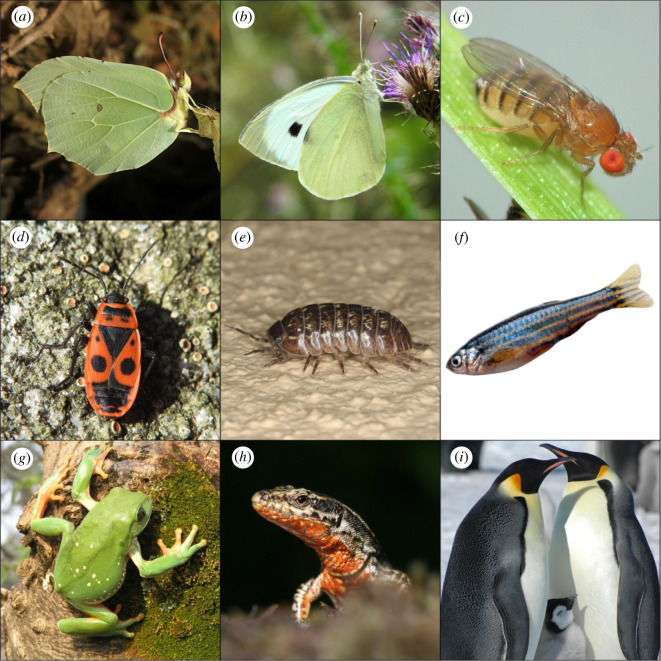

Figure 1.

Diversity of pterin pigmentation across animals. The pigment type for each example is indicated in parenthesis. (a) Gonepteryx rhamni (xanthopterin, yellow); (b) Pieris brassicae (leucopterin, white); (c) Drosophila melanogaster (drosopterin, isodrosopterin and aurodrosopterin, orange-red); (d) Pyrrhocoris apterus (erythropterin and violapterin, orange-red); (e) Armadillidium vulgare (sepiapterin, yellow); (f) Danio rerio (sepiapterin, yellow); (g) Agalychnis dacnicolor (pterorhodin, putatively contributing to green on dorsum); (h) Podarcis muralis (drosopterin, orange-red); (i) Aptenodytes forsteri (spheniscin, yellow). Photo credits are given in the acknowledgements.

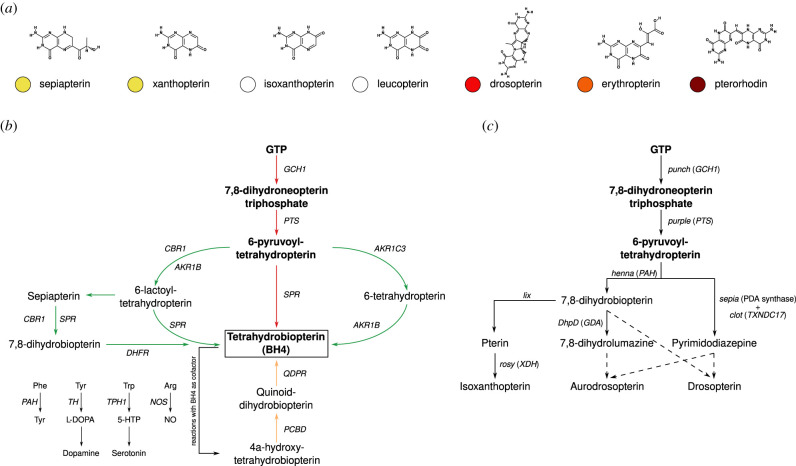

Figure 2.

Pigmented pterins and their synthesis in animals. (a) Two-dimensional structure and typical hue (human visual perception) of some of the most common pterins that are involved in pigmentation. Two-dimensional structures retrieved from the PubChem database [20]. (b) Tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis pathways: ‘de novo’ (red), ‘regeneration’ (orange) and ‘salvage’ (green) pathways. Panel adapted from the KEGG pathway map for folate synthesis [21]. (c) Drosophila melanogaster isoxanthopterin and drosopterin synthesis pathways. Panel adapted from [22,23]. Whenever possible, D. melanogaster gene names are accompanied by indication of their human orthologue (in parenthesis). Dashed lines indicate condensation reactions.

Our aim is to provide an overview on pterin pigmentation in animals. Like the better studied melanins and carotenoids, pterins are ubiquitous across animal taxa; unlike melanins, which are more frequently used for cryptic coloration across animals, pterins are more likely to be involved with generating bright pigmentation, serving key advertising roles; unlike carotenoids, they are produced endogenously. Therefore, understanding their biology is key to unravel the processes that promote or constrain the evolution of different coloration types. Important earlier reviews on the chemistry and biology of pterins are available [19,24–28], but these have focused mostly on basic biochemistry or medical aspects. Given the vital importance of colour in animal biology and the ubiquity of pterin pigmentation, we aim to promote reinvigorated interest in this topic in an era when exciting technological developments make the study of pterins as animal pigments a promising avenue to test both long-standing and emerging questions in ethology, ecology and evolutionary biology.

2. Pterin biochemistry

Pterins are heterocyclic compounds (part of the larger pteridine group) in which a pteridine ring system (composed of pyrimidine and pyrazine rings) features an amino group at position 2 and a keto group at position 4. The pterin biosynthesis pathway is composed of three major enzymatic steps that convert guanosine triphosphate (GTP) into tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). BH4, in turn, is an important redox cofactor in the synthesis of tyrosine, neurotransmitters (dopamine and serotonin) and nitric oxide (figure 2b), while also promoting cell proliferation and scavenging of H2O2 [27,29]. Pterins or their derivatives function as cofactors in many enzymatic reactions, and deficiencies in their production is linked with severe health and developmental disorders such as phenylketonuria, neurological diseases and impaired growth in humans and mice. If complete loss of function occurs, premature death or severe phenotypic disorders are common [28].

The first reaction of the pathway converts GTP into 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate (H2NTP), which is then converted to 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin (PTP), which is finally converted into BH4. Three enzymes (with little sequence identity among them) control these three steps, respectively: GTPcyclohydrolase I (in humans coded by the gene GCH1), 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase (coded by PTS) and sepiapterin reductase (coded by SPR). Owing to multiple whole genome duplication events that occurred during the evolution of teleost fish and amphibians, paralogs of GCH1 and SPR have been identified in these groups [30]. In mice a pseudogene of a SPR-like gene has also been identified and characterized [31].

After acting as a cofactor to aromatic amino acid hydroxylases (phenylalanine 4-hydroxylase, tyrosine 3-hydroxylase, tryptophan 5-hydroxylase) and nitric oxide synthase, BH4 is regenerated through the action of pterin-4-alpha-carbinolamine dehydratase 1 (coded by PCBD1, partially redundant with its homologue, PCBD2, [32]) and quinoid dihydropteridine reductase (coded by QDPR). Apart from the ‘de novo’ and ‘regeneration’ BH4 pathways, a ‘salvage’ pathway converts non-enzymatically modified sepiapterin into BH4 through SPR and dihydrofolate reductase (coded by DHFR). Also, the roles of SPR in the ‘de novo’ and ‘salvage’ pathways are complemented by the action of three other enzymes that metabolize the same substrates: carbonyl reductase 1 (CBR1), aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B (AKR1B1) and aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3).

Notably, the major steps in the BH4 synthesis pathway are essentially conserved across vertebrates and invertebrates (having been mostly studied in humans, rodents and fruit flies), and are even strikingly similar to those in many bacteria [33]. The fact that the molecular pathways used for pterin production are nearly identical across taxa suggests that they play vital cellular roles across highly divergent organisms.

3. Pterins as animal pigments

A large variety of pterin compounds are used by animals for coloration [19]. The molecules that are most commonly identified are xanthopterin, isoxanthopterin, leucopterin, drosopterin and the similar aurodrosopterin, erythropterin and sepiapterin (figure 2a). These metabolites typically absorb light at wavelengths less than 400 nm, but differ markedly in their absorbance at other wavelengths [34]. For example, leucopterin does not absorb light at wavelengths greater than 400 nm, hence the white colour of the wings of many pierids. Detection of specific pterin metabolites in biological tissues is frequently performed through analytical techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, Raman spectroscopy or absorption spectroscopy, typically comparing the profiles obtained from a tissue sample to standards for each known metabolite. With few exceptions (such as spheniscin, see below), most coloured pterins are shared by highly divergent animal taxa and impart similar hues, even when present in different tissues. For example, drosopterin underlies red coloration in the eyes of fruit flies and the skin of lizards (figure 1c,h). The colour of these pterins can also be modified in vivo, not only through interactions with other pigments and reflecting structures [35], but also depending on the pH of the cellular environment or the redox state of the molecule [36]. Although in this review we are concerned mostly with the pigmentary function of pterins, they also contribute to animal coloration in other ways, such as scattering light when in crystalline form in vertebrate eyes [37] and as bioluminescent compounds in myriapods [38].

Pterins have been described in many animal taxa (see table 1 for a selected list). Insects are the taxa from which pterins were initially isolated, so multiple instances of pterin-based pigmentation are known [39,40]. In these animals, pterins are usually deposited as granules in the cuticle or the underlying epidermis. In hornets, for example, xanthopterin-containing granules, composed by an outer shell and a core of microfibrils and axoneme, are formed some days before and after the eclosion of the adult form and underlie the typical aposematic yellow colour of these insects [41,42]. In some cases, such as in the silkworm lemon mutant, sepiapterin-containing granules are found in the underlying hypodermis [43]. Pterins are frequently found in butterfly wings, incorporated into the scales. They also have an important role in compound eyes as screening pigments, occurring in ommatidia together with ommochromes to help modulate incoming light towards visual pigments; in parallel, they also impart colour to the eye [44]. In the eyes of Drosophila melanogaster (figure 1c), drosopterins concentrate mostly inside elliptical Golgi-related granules termed pterinosomes, inside which pigment synthesis likely takes place [45,46]. In many insects, pterins accumulate in the eye throughout the adult stage (in many cases linearly), due to minimal decay, which enables their use as biomarkers of age [47]. In other arthropod groups, there are fewer examples of pterin-based pigmentation, though this is likely due to lack of studies. In crustaceans, pterin-based pigmentation has been confirmed in several groups [44,48–50] (figure 1e), while in arachnids they have yet to be isolated ([51], but indirect evidence from microscopy [52] and transcriptomics [53] is known). In non-arthropod invertebrates, pterins are also likely to contribute to pigmentation in brittle stars [54].

Table 1.

Examples of pterin pigmentation across animal taxa, with information on the most relevant compound that was identified and possible biological function.

| species | common name | clade | pterins | proposed function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonepteryx rhamni | common brimstone | Lepidoptera (Pieridae) | xanthopterin | sexual selection |

| Pieris brassicae | cabbage butterfly | Lepidoptera (Pieridae) | leucopterin | sexual selection |

| Phoebis argante | apricot sulfur | Lepidoptera (Pieridae) | erythropterin | sexual selection |

| Vespa orientalis | oriental hornet | Hymenoptera (Vespidae) | xanthopterin | aposematism |

| Drosophila melanogaster | fruit fly | Diptera (Drosophilidae) | drosopterin, isodrosopterin and aurodrosopterin | screening pigment |

| Pyrrhocoris apterus | European firebug | Hemiptera (Pyrrhocoridae) | erythropterin and violapterin | aposematism |

| Oncopeltus fasciatus | large milkweed bug | Hemiptera (Lygaeidae) | erythropterin | aposematism |

| Armadillidium vulgare | common pill-bug | Malacostraca (Armadillidiidae) | sepiapterin | uncertain |

| Platynereis dumerilii | - | Polychaeta (Nereididae) | pterorhodin, nerepterin and platynerepterin | visual pigments |

| Lucania goodei | bluefin killifish | Actinopterygii (Fundulidae) | xanthopterin, drosopterin | sexual selection |

| Danio rerio | zebrafish | Actinopterygii (Cyprinidae) | sepiapterin | sexual selection |

| Agalychnis dacnicolor | Mexican leaf frog | Anura (Phyllomedusidae) | pterorhodin | camouflage |

| Micrurus fulvius | Eastern coral snake | Squamata (Elapidae) | drosopterin | aposematism |

| Lampropeltis elapsoides | scarlet kingsnake | Squamata (Colubridae) | drosopterin | Batesian mimicry |

| Acanthodactylus erythrurus | spiny-footed lizard | Squamata (Lacertidae) | drosopterin | deflectance |

| Anolis pulchellus | Puerto Rican bush anole | Squamata (Dactyloidae) | drosopterin, isodrosopterin and neodrosopterin | sexual selection |

| Aptenodytes forsteri | emperor penguin | Aves (Spheniscidae) | spheniscin | sexual selection |

Some instances of pterin-based pigmentation in insects are worth singling out. Some butterfly species synthesize pterorhodin [55], which is uncommon in most animal taxa — apart from butterflies it has been described in frogs [56], polychaete worms [57], and likely in the iris of multiple bird species (it is suspected to colour the eyes of the red-eyed vireo [58], and was detected in the eyes of the common loon (J Hudon 2021, personal communication)). In blue-tailed damselflies, the epidermis harbours a layer with pterin-containing nanospheres, which both absorb and scatter light, contributing to create a range of colours from blue to green and brown [59]. Another special case occurs in males of pierids, in which pterins accumulate in small beads located in ridges and cross-ribs of wing scales [60]. These beads (which vary in size, shape and pterin content between species) allow for increased absorption of short-wavelength light and an increase in the refractive index of long-wavelength light [61].

Pterins are also associated with pigmentation in almost all of the major vertebrate groups. The disposition of pigmentary cells often seen in vertebrate skin forms the dermal chromatophore unit [62], which is composed by an outer layer of xanthophores (which harbour pterins or carotenoids), followed by iridophores (guanine crystals that scatter light) and melanophores (with melanin pigments). All dermal cell types originate from the neural crest cell population, and thus share a similar developmental path [63]. In xanthophores, pterins are concentrated in intra-cytoplasmic organelles termed pterinosomes, formed by a three-layered outer membrane and a variable internal arrangement of pterin-containing membranes, depending on the developmental stage [64–69]. Developmentally, pterinosomes are homologous to melanin-containing melanosomes, and seem to share a similar dual origin from the Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum, as lysosome-related organelles [70,71]. Many of the same pterins that have been associated with pigmentation in invertebrates have also been implicated in coloration in the dermis of fish, amphibians and reptiles. In birds and mammals, pterins are absent as dermal pigments.

Exceptions to this classic model of pterinosome-containing xanthophores in vertebrates are known. For example, anurans are known to deposit small but non-negligible quantities of isoxanthopterin within iridophores of white ventral skin, where they presumably contribute towards the reflecting properties of those cells [72]. Also, phyllomedusine frogs (figure 1g) possess dark red pterin-depositing melanosomes, which contain the pterin dimer pterorhodin [56]. These compound organelles (pterino-melanosomes) undergo initial development as melanin-containing melanosomes, but at a later stage start to deposit concentric fibres of pterorhodin around a central kernel of eumelanin. These ‘pterino-melanosomes’ have not been found outside this group of frogs. Another (possible) example of pterin-based dermal pigmentation in vertebrates, and the only instance so far described in bird feathers, was identified in yellow feather barbs of penguins [73] (figure 1i). These pigments, termed ‘spheniscins’, exhibit chemical and spectral characteristics similar to pterins (nitrogen-rich, fluorescent), but absorbance and Raman spectra do not match any known compound, which has so far prevented an unambiguous assignment [73,74]. Apart from dermal pigmentation, pterins are also present as eye pigments in ectothermic vertebrates [75] and birds [76,77]. In this latter case, they are deposited in the pigmented epithelium of the iris in close association with reflecting elements such as guanine crystals, or in some cases appearing in crystalline form [37]. Xanthopterin and isoxanthopterin, known to appear in crystalline form in the eye of some crustaceans [78] and vertebrates [79,80], are likely candidates to contribute to eye pigmentation in vertebrates.

4. The signalling functions of pterins

Colours can serve multiple functions in animal communication. In intraspecific communication, coloration can signal an individual's physiological condition, social rank or reproductive state [81]. In interspecific communication, coloration can impart information on toxicity, deflect predators towards non-vital body parts, improve camouflage or promote species recognition [82]. Pterins have been linked to many of these basic functions. Most colourful pterins typically absorb short-wavelength light, reflecting mostly in the yellow-red range (depending however on the scattering properties of the containing medium), which means that they are typically linked to conspicuous coloration. They have thus been mostly associated with functions such as aposematic signalling to predators and as conveyors of individual quality in the context of sexual selection. Of course, conspicuous pigmentation does not necessarily mean signalling is the primary function of pterins: for example, red drosopterins in the eyes of some species of brachyceran flies serve mainly to promote the regeneration of visual pigments [83].

In interspecific communication, pterins have been most frequently linked to aposematic signals, such as those of butterflies. A well-studied example is that of polymorphic wood tiger moth females, whose hindwings range from yellow to red due to the deposition of erythropterins [84]. Experiments show that these females are rejected more frequently by avian predators when compared with non-conspicuous moths used as controls, and this effect is still significant within species, since red tiger moths are less predated than orange tiger moths [85]. Similar effects were recorded in the European firebug, in which darker red-orange forms are more efficient in deterring predators [86] (figure 1d). The red colour of aposematic coral snakes and many of its Batesian mimics likely arose from convergent evolution of drosopterin production in skin [87,88]. Despite this strong association between pterins and an aposematic function, few studies have explicitly evaluated whether these pigments are functioning as honest signals of toxicity, and evidence is mixed. For example, in paper wasps, brighter yellow coloration is correlated with larger poison glands [89], while in cotton harlequin bugs there is no association between the extent of erythropterin-mediated red colour and toxicity [90]. Another use for bright pterins in predator deterrence is as deflectors: in spiny-footed lizards, the red tails of juveniles are likely to divert attacks from predatory birds away from the body [91,92].

Although pterins are usually associated with conspicuous colours, they can also contribute to camouflage in some species. For example, pterorhodin in phyllomedusine frogs contributes together with other pigments to create the green dorsal hue of these amphibians. Although the exact mechanisms are not well understood, the presence of pterorhodin coupled with reduced melanin in chromatophores leads to increased reflectance of near-infrared light, mimicking the chromatic properties of leaves [93]. Pterins also generate cryptic blue-green-brown coloration in blue-tailed damselflies through a combination of structural and pigmentary mechanisms [59].

Signalling in a reproductive context has been another of the primary functions ascribed to pterins. Examples of these pigments creating sexually dichromatic signals can be found in insects [35,60,94,95], fish [96,97], reptiles [69,98,99] and amphibians [100]. Sexual dichromatism in a visual trait may not necessarily mean that the trait is implicated in sexual selection; for example, it could be associated with differential susceptibility of males and females to predators leading to enhanced aposematic displays in one of the sexes. However, in most of these species an explanation rooted in sexual selection is the most likely one.

In coloration biology, one aspect that has been the subject of vigorous research is if and how conspicuous visual signals employed in communication function as honest signals of individual quality, social status or toxicity. Much of this attention has been centred on whether coloration acts as a reliable signal of quality because pigments or their precursors are costly to acquire or if it acts as an index due to being inextricably linked to vital physiological processes [101]. Endogenously produced pigments have been frequently shown to have relatively lower signal value, or at least conveying different information about an individual's status, presumably because their precursors are not as costly to acquire. This debate has been driven in large part by studies in birds [102–104], for which melanin is typically linked to a cryptic function (but many examples show melanins contribute to non-cryptic displays, e.g. [105–107]), while dietary carotenoids are typically used for bright displays. Pterins can play a major role in informing this debate given they are predominantly used for conspicuous signalling, so should be a prime target to test if the relative importance of resource allocation versus linkage to vital pathways is maintained across major pigment types. Production costs of pterins are thought to be negligible, since they are synthesized de novo from the abundant purine GTP; on the other hand, pterin metabolism is vital to multiple physiological functions. Evidence for the association between the intensity or extent of pterin-based coloration and different measures of individual quality has been contradictory [97,108–112]. For example, in pierid butterflies nitrogen intake during the larval phase is correlated with the intensity of leucopterin-based coloration in the adult wing [109]; whereas in male water dragons the intensity of drosopterin-based red colour is negatively associated with parasite resistance and body size [111].

Given this uncertain role of pterins in signalling condition, and since similarly hued carotenoids that more readily correlate with individual quality are present in many species, why are not the latter favoured as a source of ornamentation? A potential explanation is that pterins may compensate for lower environmental availability of carotenoids. In guppies, interpopulation differences in drosopterin concentration serve to maintain a stable, population-specific pterin : carotenoid ratio in a sexually selected signal, thus maintaining the state of the signal across populations [113]. In agamid lizards, environments with lower productivity are correlated with lower carotenoids concentrations, but with higher pterin concentrations, again suggesting that pterins may compensate for lower availability of carotenoids [114]. However, similarly coloured pterins and carotenoids are not particularly correlated in these lizards, which suggest that compensation of carotenoids by pterins may not be a linear process. A clearer understanding of the molecular pathways implicated in generating pterin-based coloration is likely to shed some light on the relationships between colour and what is being signalled (e.g. [115,116]). For example, knowing the identity of the genes involved in the expression of a conspicuous signal allows testing hypotheses that link the activity of genes involved with the multiple processes underlying signal expression (production, transport and deposition), multiple measures of individual condition and signal content itself to determine if pterin-based colour acts as a signal due to acquisition costs or due to its processing being linked to vital metabolic pathways.

5. Molecular mechanisms underlying pigmentation

The expression of pigment-based colour depends on the development of specialized pigment-producing cells and organelles, as well as on the production, transport and deposition of pigments within and between cellular compartments. Each of these processes depends on the interaction of several genes. A large portion of our current knowledge on the molecular basis of pterin-based pigmentation has been amassed from Drosophila mutants. The first fruit fly mutant described by Thomas Hunt Morgan was white, which featured loss of pterins and ommochromes in the eye [117]. The white locus has since been shown to code for a subunit of an ABC membrane transporter, with mutants having an impaired ability to transfer substrates of pigment synthesis into pterinosomes [118]. Intracellular trafficking of proteins and pterin precursors also mediate other eye colour mutants in this species [119,120], although these tend to impact on various pigment types, not just pterins. Another indirect route to altering pterin pigmentation can arise through impairment of purine synthesis, which impacts the availability of precursor molecules for pigment biosynthesis [121].

Genes specifically linked to pterin biosynthesis have been described from several mutants (figure 2c). One the most well known is rosy, which maps to xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH), and that is characterized by brown eyes (containing only ommochromes), lacking isoxanthopterin and having reduced drosopterin [122]. XDH has also been shown to oxidize a number of pterins in the wings of pierid butterflies [123], and mutations in this gene are associated with differences in coloration patterns in bumblebees [124]. Isoxanthopterin biosynthesis is also impaired in lix mutants, which lack activity of a yet unidentified dihydropterin oxidase that acts upstream of XDH [22]. Other genes linked to disruptions of key steps in the biosynthesis of drosopterin and aurodrosopterin in the eye of fruit flies include several homologues of mammalian genes involved with pterin and purine metabolism [125–131] (figure 2c), as well as the fruit fly gene for pyrimidodiazepine synthase [132]. These results suggest that the biosynthesis of colourful pterins shares the initial conversion steps of the main ‘de novo’ BH4 pathway before diverging into parallel pigment-related pathways [23]. In water strider embryos, xanthopterin and erythropterin-based pigmentation has been shown to depend on many of the same biosynthetic steps that govern pterin-based eye colour in fruit flies, suggesting a deep conservation of the molecular mechanisms producing these pigments in insects [133].

Important insights into the genetics of pigmentation driven by pterins in insects have also been provided by butterfly models. The silkworm lemon mutant, characterized by an excess deposition of yellow sepiapterin in the epidermis of larvae, has been linked to several mutations in SPR [134]. In the same species, other mutations manifesting altered colour and lethality in second-instar larvae have been mapped to PTS [135,136]. The ‘alba’ polymorphism of female pierid butterflies is caused by variation in the homeobox transcription factor BarH-1, which interferes with pigment granule formation in wing scales [137]. In the fruit fly, this same gene is also required for pigment granule formation in ommatidia [138].

In vertebrates, most information has been attained through the study of pigmentation in zebrafish, which exhibits alternate blue-yellow coloured stripes, the latter caused by sepiapterin-pigmented xanthophores [139] (figure 1f). A wealth of colour mutants affecting xanthophore development and pigment synthesis have been identified [140], with most studies focusing on the differentiation of pigment cell types from the neural crest and their interactions, uncovering crucial genes for xanthophore differentiation [141–144]. Of particular interest for pigment synthesis, XDH in zebrafish is also likely to act in the oxidation of sepiapterin to isoxanthopterin and other colourless pterins, which suggests strong conservation in the parallel pathways for pterin pigment production between vertebrates and insects [145].

Recent studies from non-model vertebrates have also yielded key insights. In the common wall lizard (figure 1h), the orange colour morph is controlled by a tissue-specific cis-regulatory allele of SPR associated with increased drosopterin accumulation in the xanthophores of ventral skin [146]. The exact role of SPR in drosopterin synthesis in lizards is unclear, since this link has not been established in insect models. In another recent finding, the membrane transporter SLC2A11B was shown to regulate pterin-based eye colour in xanthophore-like iris pigment cells of pigeons [147–149]. Interestingly, this gene is also involved in xanthophore differentiation in medaka [150], but the exact cellular and molecular links between these two cases (pigment uptake versus cell differentiation) are unknown. In vertebrates, like in some fruit fly mutants described above, disrupting lysosome-related organelles can also impact pterin-based pigmentation (and other pigment types), as shown in the corn snake [71]. Knowledge on the general molecular pathways that are correlated with pterin pigmentation in vertebrates has also been further complemented by gene expression assays in fish [151–153], amphibians [154,155] and reptiles [156].

Pterins participate in vital housekeeping functions (see above, also [27,29]), and impairment of their normal metabolism leading to severe deleterious effects has often been reported in medical studies [28]. Likewise, colour variants related with changes to pterin metabolism are usually associated with multiple pleiotropic effects. For example, in silkworm lemon mutants sepiapterin accumulation is associated with behavioural changes (in locomotor ability) due to impairment of BH4-mediated neurotransmitter production [157]. Fruit fly mutants described above also show frequent pleiotropic effects associated with eye colour change, including lethality [125,126]. Co-option of housekeeping genes is increasingly recognized as a source of pigmentation novelty [158,159], but these developmental opportunities need to be balanced by the need to offset deleterious effects of mutations affecting biosynthesis of BH4 or its essential precursors. In wild populations, tissue-specific regulatory variation is likely to play a major role in diminishing pleiotropic constrains, as was shown for wall lizards [146] and pierid butterflies [137]. These two examples are classic cases of stable colour polymorphisms associated with alternative life-history strategies and behaviour, so even when non-coding variation affects pterin synthesis in peripheral tissues such as the integument, pleiotropic effects could be expected as a by-product. These and other animal models (both wild and captive) thus yield immense promise to investigate proximate and ultimate mechanisms associated with the evolution of pterin pigmentation.

6. Open questions and future directions in pterin research

Many questions remain on the evolutionary and functional implications of pterin-based coloration in animals. For example, there is still limited understanding of the taxonomic extent of this class of pigments, which has been recorded almost exclusively in vertebrates and insects. Given that similar colourful pterins have evolved in these two highly divergent groups, many other animal lineages could potentially express these pigments. This lack of basic knowledge highlights the challenges, but also the opportunities, that lie ahead in this field.

There is very little understanding on why animals use pterins as signals. While specific functions have been identified in many taxa, it is unclear what underlying properties of pterins make them an often-preferred pigment. Are they just evolutionarily labile, or does signal honesty promote the maintenance of these ornaments once they evolve? They are widespread as aposematic signals, but pterins themselves are not known to be toxic, so is this link strictly maintained through selection? In the context of sexual selection, more work needs to be carried out to understand if, and in what circumstances, colourful pterins signal individual quality. Is nitrogen intake, for example, a limiting factor signalling a trade-off between physiology and ornamentation (the costly signalling hypothesis), or are colourful pterins used as signals because they are connected with vital functions (the index hypothesis)? In many species, both pterins and dietary carotenoids are simultaneously used for bright yellow-red coloration (the dewlap of anole lizards is one such example), making this a further challenge to understand the context in which either pigment type evolved.

Central questions on the genes and pathways involved with the synthesis of colourful pterins remain. The major steps in these pathways have received a reasonable amount of attention in fruit flies, but generalization to other animals remains elusive. This is particularly true for vertebrates, for which less than a handful of studies have been conducted, despite pterin pigmentation arising convergently multiple times. Major open questions in this regard include whether the parallel pathways that produce these pigments are conserved among animals, or if the central housekeeping genes in the pterin synthesis and regeneration pathways are recurrently co-opted for pigmentation. Are genes involved with the synthesis of these compounds more readily co-opted for pigmentation, or are mechanisms affecting transport or uptake less likely to lead to harmful pleiotropic effects? Related to this, how do changes in pterin metabolism for pigmentation impact fitness? In many species, polymorphism in pterin coloration is associated with alternative life-history strategies, but a mechanistic explanation for these associations is still lacking. On a more fundamental level, why have colourful pterins never been described in many animal taxa? Does this result simply from a lack of studies, or are some taxa constrained in their capacity to co-opt the pterin pathway for pigmentation?

A crucial factor in answering many of these questions will be the choice of model species. Abundant experimental and analytical resources available for established models like fruit flies or zebrafish can provide additional detailed knowledge, but focusing on alternative, less well-studied taxa that exhibit variation in pterin pigmentation in either natural or domesticated populations could open the door for a more comprehensive understanding of the evolutionary processes implicated in the evolution of these pigments. Particularly promising models discussed in this review include several polymorphic species of butterflies [60,61,84,109,137], odonates [59,160], heteropterans [86,161], fish [152,153] and squamates [99,110,146,156]. Many of these species are amenable to experimentation in the lab, or are relatively easy to access for sampling and studying in the field (or both).

To take full advantage of these opportunities, traditional approaches in ecology, ethology, colour measurement, genomics and biochemistry can be combined with recent technological advances in molecular biology: these include techniques for profiling transcriptomes [162,163], epigenomes [164,165] and metabolomes [166], as well as genome editing [167–169]. For example, to understand if and how a pterin ornament is involved in honest signalling for sexual selection in a given species, traditional measures of individual quality could be integrated with spectrophotometry and cell-level transcriptomics and metabolomics to quantitatively address links between colour variation, physiology and cellular function in tissues involved with pigment production and key fitness traits such as hormone production or gametogenesis. Future research in this field should thus strive for comprehensive, holistic approaches to improve our understanding on the actual signalling content of colour, how it evolves and how it interacts with other aspects of organismal functioning. Generating extensive phenotypic and genomic datasets is becoming increasingly easier and cheaper for non-model species—the time is ripe for advancing pterin research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rui Faria, Paulo Pereira and Guillem Pérez i de Lanuza for helpful comments on the manuscript. Credits for specific photographs from figure 1 are as follows: (a) and (c) Rui Andrade; (b) and (d) Pedro Andrade; (e) Donald Hobern (CC-BY-2.0); (f) Pogrebnoj Alexandroff (CC BY-SA 3.0); (g) David Valenzuela; (h) Guillem Pérez i de Lanuza; (i) Denis and Chris Luyten-De Hauwere (public domain).

Contributor Information

Pedro Andrade, Email: pandrade@cibio.up.pt.

Miguel Carneiro, Email: miguel.carneiro@cibio.up.pt.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

M.C. and P.A. conceived the manuscript. P.A. wrote an initial draft. M.C. revised the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

P.A. was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) through a research contract in the scope of project PTDC/BIA-EVL/28621/2017. M.C. was supported by FCT through POPH-QREN funds from the European Social Fund and Portuguese MCTES (CEECINST/00014/2018/CP1512/CT0002).

References

- 1.Cuthill IC, et al. 2017The biology of color. Science 357, aan0221. ( 10.1126/science.aan0221) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grether GF, Kolluru GR, Nersissian K. 2004Individual colour patches as multicomponent signals. Biol. Rev. 79, 583-610. ( 10.1017/S1464793103006390) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shawkey MD, D'Alba L. 2017Interactions between colour-producing mechanisms and their effects on the integumentary colour palette. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160536. ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0536) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Wortsman J. 2004Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol. Rev. 84, 1155-1228. ( 10.1152/physrev.00044.2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoekstra HE, Hirschmann RJ, Bundey RA, Insel PA, Crossland JP. 2006A single amino acid mutation contributes to adaptive beach mouse color pattern. Science 313, 101-104. ( 10.1126/science.1126121) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenblum EB, Römpler H, Schöneberg T, Hoekstra HE. 2010Molecular and functional basis of phenotypic convergence in white lizards at White Sands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2113-2117. ( 10.1073/pnas.0911042107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes RJ, et al. 2016Genetic basis for red coloration in birds. Curr. Biol. 26, 1427-1434. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.076) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toews DP, Hofmeister NR, Taylor SA. 2017The evolution and genetics of carotenoid processing in animals. Trends Genet. 33, 171-182. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2017.01.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gazda MA, et al. 2020A genetic mechanism for sexual dichromatism in birds. Science 368, 1270-1274. ( 10.1126/science.aba0803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins FG. 1889Note on a yellow pigment in butterflies, Proc. Chem. Soc. 5, 117. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins FG. 1891Pigment in yellow butterflies. Nature 45, 197-198. ( 10.1038/045197c0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins FG. 1895XV. The pigments of the Pieridæ: a contribution to the study of excretory substances which function in ornament. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 186, 661-682. ( 10.1098/rstb.1895.0015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths AB. 1892Recherches sur les couleurs de quelques insectes. Compt. rend. Acad. Paris. 115, 958-959. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wieland H, Schöpf C. 1925Über den gelben Flügelfarbstoff des Citronenfalters (Gonepteryx rhamni). Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series) 58, 2178-2183. ( 10.1002/cber.19250580942) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schöpf C, Wieland H. 1926Über das Leukopterin, das weiße Flügelpigment der Kohlweißlinge (Pieris brassicae und P. napi). Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series) 59, 2067-2072. ( 10.1002/cber.19260590865) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purrmann R. 1940Über die Flügelpigmente der Schmetterlinge. VII. Synthese des Leukopterins und Natur des Guanopterins. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 544, 182-190. ( 10.1002/jlac.19405440111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purrmann R. 1941Die Synthese des Xanthopterins. Über die Flügelpigmente der Schmetterlinge. X3. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 546, 98-102. ( 10.1002/jlac.19415460107) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieland H, Decker P. 1941Über die Flügelpigmente der Schmetterlinge. XI. Methylierung und Molekulargewicht von Leukopterin. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 547, 180-184. ( 10.1002/jlac.19415470112) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfleiderer W. 1993Natural pteridines—a chemical hobby. In Chemistry and biology of pteridines and folates (eds S Milstien, G Kapatos, RA Levine, B Shane), pp. 1-16. Boston, MA: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, et al. 2021PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1388-D1395. ( 10.1093/nar/gkaa971) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanehisa M, Goto S. 2000KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27-30. ( 10.1093/nar/28.1.27) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva FJ, Escriche B, Ordoño E, Ferré, J. 1991Genetic and biochemical characterization of little isoxanthopterin (lix), a gene controlling dihydropterin oxidase activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 230, 97-103. ( 10.1007/BF00290656) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Kim K, Yim J. 2013Biosynthesis of drosopterins, the red eye pigments of Drosophila melanogaster. IUBMB Life 65, 334-340. ( 10.1002/iub.1145) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gates M. 1947The chemistry of the pteridines. Chem. Rev. 41, 63-95. ( 10.1021/cr60128a002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziegler I, Harmsen R. 1970The biology of pteridines in insects. In Advances in insect physiology (eds JWL Beament, JE Treherne, V Wigglesworth), vol. 6, pp. 139-203. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rembold H, Gyure WL. 1972Biochemistry of the pteridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. English 11, 1061-1072. ( 10.1002/anie.197210611) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thöny B, Auerbach G, Blau N. 2000Tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis, regeneration and functions. Biochem. J. 347, 1-16. ( 10.1042/bj3470001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longo N. 2009Disorders of biopterin metabolism. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 32, 333-342. ( 10.1007/s10545-009-1067-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Werner ER, Blau N, Thöny B. 2011Tetrahydrobiopterin: biochemistry and pathophysiology. Biochem. J. 438, 397-414. ( 10.1042/BJ20110293) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braasch I, Schartl M, Volff JN. 2007Evolution of pigment synthesis pathways by gene and genome duplication in fish. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 1-18. ( 10.1186/1471-2148-7-74) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SW, Park IY, Hahn Y, Lee JE, Seong CS, Chung JH, Park YS. 1999Cloning of mouse sepiapterin reductase gene and characterization of its promoter region. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gene Struct. Expr. 1445, 165-171. ( 10.1016/S0167-4781(99)00030-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rose RB, Pullen KE, Bayle JH, Crabtree GR, Alber T. 2004Biochemical and structural basis for partially redundant enzymatic and transcriptional functions of DCoH and DCoH2. Biochemistry 43, 7345-7355. ( 10.1021/bi049620t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feirer N, Fuqua C. 2017Pterin function in bacteria. Pteridines 28, 23-36. ( 10.1515/pterid-2016-0012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wijnen B, Leertouwer HL, Stavenga DG. 2007Colors and pterin pigmentation of pierid butterfly wings. J. Insect. Physiol. 53, 1206-1217. ( 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.06.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutowski RL, Macedonia JM, Morehouse N, Taylor-Taft L. 2005Pterin pigments amplify iridescent ultraviolet signal in males of the orange sulphur butterfly, Colias eurytheme. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 2329-2335. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3216) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saenko SV, Teyssier J, Van Der Marel D, Milinkovitch MC. 2013Precise colocalization of interacting structural and pigmentary elements generates extensive color pattern variation in Phelsuma lizards. BMC Biol. 11, 105. ( 10.1186/1741-7007-11-105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliphant LW, Hudon J. 1993Pteridines as reflecting pigments and components of reflecting organelles in vertebrates. Pigment Cell Res. 6, 205-208. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1993.tb00603.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuse M, Kanakubo A, Suwan S, Koga K, Isobe M, Shimomura O. 20017,8-Dihydropterin-6-carboxylic acid as light emitter of luminous millipede, Luminodesmus sequoiae. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 1037-1040. ( 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00122-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vukusic P, Chittka L. 2013Visual signals: color and light production. In The insects: structure and function (eds Chapman RF, Simpson SJ, Douglas AE), 5th edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ( 10.14411/eje.2014.021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shamim G, Ranjan SK, Pandey DM, Ramani R. 2014Biochemistry and biosynthesis of insect pigments. EJE 111, 149-164. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plotkin M, Volynchik S, Barkay Z, Bergman DJ, Ishay JS. 2009Micromorphology and maturation of the yellow granules in the hornet gastral cuticle. Zool. Res. 30, 65-73. ( 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2009.01065) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plotkin M, Volynchik S, Ermakov NY, Benyamini A, Boiko Y, Bergman DJ, Ishay JS. 2009Xanthopterin in the oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis): light absorbance is increased with maturation of yellow pigment granules. Photochem. Photobiol. 85, 955-961. ( 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00526.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsujita M, Sakurai S. 1963Specific protein combining with yellow pigments (Dihydropteridine) in the silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Proc. Japan Acad. 38, 97-105. ( 10.1266/jjg.38.97) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stavenga DG. 1989Pigments in compound eyes. In Facets of vision (eds DG Stavenga, RC Hardie), pp. 152-172. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoup JR. 1966The development of pigment granules in the eyes of wild type and mutant Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 29, 223-249. ( 10.1083/jcb.29.2.223) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hearl WG, Jacobson KB. 1984Eye pigment granules of Drosophila melanogaster: isolation and characterization for synthesis of sepiapterin and precursors of drosopterin. Insect Biochem. 14, 329-335. ( 10.1016/0020-1790(84)90068-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayes EJ, Wall R. 1999Age-grading adult insects: a review of techniques. Physiol. Entomol. 24, 1-10. ( 10.1046/j.1365-3032.1999.00104.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox DL. 1953Animal biochromes and structural colours. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waywell EB, Corey S. 1972The occurrence and distribution of pteridines and purines in crayfish (Decapoda, Astacidae). Crustaceana 22, 294-302. ( 10.1163/156854072X00589) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakagoshi M, Takikawa S, Negishi S, Tsusué M. 1992Pteridines in the yellow-colored chromatophores of the isopod, Armadillidium vulgare. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 373, 1249-1254. ( 10.1515/bchm3.1992.373.2.1249) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsiung BK, Shawkey MD, Blackledge TA. 2019Color production mechanisms in spiders. J. Arachnol. 47, 165-180. ( 10.1636/JoA-S-18-022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schliwa M, Euteneuer U. 1979Hybrid pigment organelles in an invertebrate. Cell Tissue Res. 196, 541-543. ( 10.1007/BF00234747) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Croucher PJ, Brewer MS, Winchell CJ, Oxford GS, Gillespie RG. 2013De novo characterization of the gene-rich transcriptomes of two color-polymorphic spiders, Theridion grallator and T. californicum (Araneae: Theridiidae), with special reference to pigment genes. BMC Genomics 14, 862. ( 10.1186/1471-2164-14-862) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fontaine AR. 1962The colours of Ophiocomina nigra (Abildgaard). II. The occurrence of melanin and fluorescent pigments. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 42, 9-31. ( 10.1017/S0025315400004434) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Russell PB, Purrmann R, Schmitt W, Hitchings GH. 1949The synthesis of pterorhodin (rhodopterin) 1, 1a. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 71, 3412-3416. ( 10.1021/ja01178a042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bagnara JT. 2003Enigmas of pterorhodin, a red melanosomal pigment of tree frogs. Pigment Cell Res. 16, 510-516. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00075.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viscontini M, Hummel W, Fischer A. 1970Pigmente von nereiden (Annelida, polychaeten). 1., vorläufige mitteilung. isolierung von pterindimeren aus den augen von Platynereis dumerilii (Audouin & Milne Edwards) 1833. Helv. Chim. Acta 53, 1207-1209. ( 10.1002/hlca.19700530538) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hudon J, Muir AD. 1996Characterization of the reflective materials and organelles in the bright irides of North American blackbirds (Icterinae). Pigment Cell Res. 9, 96-104. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1996.tb00096.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henze MJ, Lind O, Wilts BD, Kelber A. 2019Pterin-pigmented nanospheres create the colours of the polymorphic damselfly Ischnura elegans. J. R. Soc. Interface 16, 20180785. ( 10.1098/rsif.2018.0785) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stavenga DG, Stowe S, Siebke K, Zeil J, Arikawa K. 2004Butterfly wing colours: scale beads make white pierid wings brighter. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 1577-1584. ( 10.1098/rspb.2004.2781) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilts BD, Wijnen B, Leertouwer HL, Steiner U, Stavenga DG. 2017Extreme refractive index wing scale beads containing dense pterin pigments cause the bright colors of pierid butterflies. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1600879. ( 10.1002/adom.201600879) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bagnara JT, Taylor JD, Hadley ME. 1968The dermal chromatophore unit. J. Cell Biol. 38, 67-79. ( 10.1083/jcb.38.1.67) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silver DL, Hou L, Pavan WJ. 2006The genetic regulation of pigment cell development. In Neural crest induction and differentiation (ed. J-P Saint-Jeannet), pp. 155-169. Boston, MA: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsumoto J. 1965Studies on fine structure and cytochemical properties of erythrophores in swordtail, Xiphophorus helleri, with special reference to their pigment granules (pterinosomes). J. Cell Biol. 27, 493-504. ( 10.1083/jcb.27.3.493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matsumoto J, Obika M. 1968Morphological and biochemical characterization of goldfish erythrophores and their pterinosomes. J. Cell Biol. 39, 233-250. ( 10.1083/jcb.39.2.233) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yasutomi M, Hama T. 1973Structural changes of drosopterinosomes (red pigment granules) during the erythrophore differentiation of the frog, Rana japonica, with reference to other pigment-containing organelles. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und Mikroskopische Anatomie 137, 331-343. ( 10.1007/BF00307207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Obika, M. 1993Formation of pterinosomes and carotenoid granules in xanthophores of the teleost Oryzias latipes as revealed by the rapid-freezing and freeze-substitution method. Cell Tissue Res. 271, 81-86. ( 10.1007/BF00297544) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alibardi L. 2013Observations on the ultrastructure and distribution of chromatophores in the skin of chelonians. Acta Zool. 94, 222-232. ( 10.1111/j.1463-6395.2011.00546.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brejcha J, et al. 2019Body coloration and mechanisms of colour production in Archelosauria: the case of deirocheline turtles. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 190319. ( 10.1098/rsos.190319) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bagnara JT, Matsumoto J, Ferris W, Frost SK, Turner WA, Tchen TT, Taylor JD. 1979Common origin of pigment cells. Science 203, 410-415. ( 10.1126/science.760198) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ullate-Agote A, et al. 2020Genome mapping of a LYST mutation in corn snakes indicates that vertebrate chromatophore vesicles are lysosome-related organelles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26 307-26 317. ( 10.1073/pnas.2003724117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bagnara JT, Kreutzfeld KL, Fernandez PJ, Cohen AC. 1988Presence of pteridine pigments in isolated iridophores. Pigment Cell Res. 1, 361-365. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1988.tb00134.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McGraw KJ, Toomey MB, Nolan PM, Morehouse NI, Massaro M, Jouventin P. 2007A description of unique fluorescent yellow pigments in penguin feathers. Pigment Cell Res. 20, 301-304. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2007.00386.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas DB, McGoverin CM, McGraw KJ, James HF, Madden O. 2013Vibrational spectroscopic analyses of unique yellow feather pigments (spheniscins) in penguins. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20121065. ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.1065) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ziegler-Günder VI. 1956Pterine: Pigmente und Wirkstoffe im Tierreich. Biol. Rev., 31, 313-345. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1956.tb01593.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oehme H. 1969Vergleichende Untersuchungen über die Färbung der Vogeliris. Biologische Zentralblatt 88, 3-35. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oliphant LW. 1987Pteridines and purines as major pigments of the avian iris. Pigment Cell Res. 1, 129-131. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1987.tb00401.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Palmer BA, et al. 2018Optically functional isoxanthopterin crystals in the mirrored eyes of decapod crustaceans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2299-2304. ( 10.1073/pnas.1722531115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hama, T. 1953Substances fluorescentes du type ptérinique dans la peau ou les yeux de la grenouille (Rana nigromaculata) et leurs transformations photochimiques. Experientia 9, 299-300. ( 10.1007/BF02156023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang G, et al. 2019Guanine and 7,8-dihydroxanthopterin reflecting crystals in the zander fish eye: crystal locations, compositions, and structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19 736-19 745. ( 10.1021/jacs.9b08849) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barnard CJ. 2004Animal behaviour: mechanism, development, function and evolution. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Caro T, Allen WL. 2017Interspecific visual signalling in animals and plants: a functional classification. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160344. ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0344) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stavenga DG, Wehling MF, Belušič, G. 2017Functional interplay of visual, sensitizing and screening pigments in the eyes of Drosophila and other red-eyed dipteran flies. J. Physiol. 595, 5481-5494. ( 10.1113/JP273674) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lindstedt C, Schroderus E, Lindström L, Mappes T, Mappes J. 2016Evolutionary constraints of warning signals: a genetic trade-off between the efficacy of larval and adult warning coloration can maintain variation in signal expression. Evolution 70, 2562-2572. ( 10.1111/evo.13066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lindstedt C, Eager H, Ihalainen E, Kahilainen A, Stevens M, Mappes, J. 2011Direction and strength of selection by predators for the color of the aposematic wood tiger moth. Behav. Ecol. 22, 580-587. ( 10.1093/beheco/arr017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Exnerová A, et al. 2006Importance of colour in the reaction of passerine predators to aposematic prey: experiments with mutants of Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera). Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 88, 143-153. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2006.00611.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kikuchi DW, Pfennig DW. 2012A Batesian mimic and its model share color production mechanisms. Cur. Zool. 58, 658-667. ( 10.1093/czoolo/58.4.658) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kikuchi DW, Seymoure BM, Pfennig DW. 2014Mimicry's palette: widespread use of conserved pigments in the aposematic signals of snakes. Evol. Dev. 16, 61-67. ( 10.1111/ede.12064) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vidal-Cordero JM, Moreno-Rueda G, López-Orta A, Marfil-Daza C, Ros-Santaella JL, Ortiz-Sánchez FJ. 2012Brighter-colored paper wasps (Polistes dominula) have larger poison glands. Front. Zool. 9, 1-5. ( 10.1186/1742-9994-9-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Medina I, Wallenius T, Head, M. 2020No honesty in warning signals across life stages in an aposematic bug. Evol. Ecol. 34, 59-72. ( 10.1007/s10682-019-10025-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fresnillo B, Belliure J, Cuervo JJ. 2015Red tails are effective decoys for avian predators. Evol. Ecol. 29, 123-135. ( 10.1007/s10682-014-9739-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cuervo JJ, Belliure J, Negro JJ. 2016Coloration reflects skin pterin concentration in a red-tailed lizard. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 193, 17-24. ( 10.1016/j.cbpb.2015.11.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schwalm PA, Starrett PH, McDiarmid RW. 1977Infrared reflectance in leaf-sitting neotropical frogs. Science 196, 1225-1226. ( 10.1126/science.860137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morehouse NI, Rutowski RL. 2010In the eyes of the beholders: female choice and avian predation risk associated with an exaggerated male butterfly color. Am. Nat. 176, 768-784. ( 10.1086/657043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Izzo AS, Tibbetts EA. 2012Spotting the top male: sexually selected signals in male Polistes dominulus wasps. Anim. Behav. 83, 839-845. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.01.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Grether GF, Hudon J, Endler JA. 2001Carotenoid scarcity, synthetic pteridine pigments and the evolution of sexual coloration in guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 1245-1253. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1624) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Johnson AM, Fuller RC. 2015The meaning of melanin, carotenoid, and pterin pigments in the bluefin killifish, Lucania goodei. Behav. Ecol. 26, 158-167. ( 10.1093/beheco/aru164) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ortiz E, Bächli E, Price D, Williams-Ashman HG. 1963Red pteridine pigments in the dewlaps of some anoles. Physiol. Zool. 36, 97-103. ( 10.1086/physzool.36.2.30155434) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Haisten DC, Paranjpe D, Loveridge S, Sinervo, B. 2015The cellular basis of polymorphic coloration in common side-blotched lizards, Uta stansburiana. Herpetologica 71, 125-135. ( 10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-13-00091) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morgan SK, Pugh MW, Gangloff MM, Siefferman L. 2014The spots of the spotted salamander are sexually dimorphic. Copeia 2014, 251-256. ( 10.1643/CE-13-085) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weaver RJ, Koch RE, Hill GE. 2017What maintains signal honesty in animal colour displays used in mate choice? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160343. ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0343) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Badyaev AV, Hill GE. 2000Evolution of sexual dichromatism: contribution of carotenoid- versus melanin-based coloration. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 69, 153-172. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2000.tb01196.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weaver RJ, Santos ES, Tucker AM, Wilson AE, Hill GE. 2018Carotenoid metabolism strengthens the link between feather coloration and individual quality. Nat. Commun. 9, 1-9. ( 10.1038/s41467-017-02649-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Griffith SC, Parker TH, Olson VA. 2006Melanin-versus carotenoid-based sexual signals: is the difference really so black and red? Anim. Behav. 71, 749-763. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.07.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gluckman TL, Cardoso GC. 2010The dual function of barred plumage in birds: camouflage and communication. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 2501-2506. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02109.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stavenga DG, Leertouwer HL, Wilts BD. 2018Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes. J. Exp. Biol. 221, 1-10. ( 10.1242/jeb.174656) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rubenstein DR, et al. 2021Feather gene expression elucidates the developmental basis of plumage iridescence in African starlings. J. Heredity esab014. ( 10.1093/jhered/esab014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weiss SL, Kennedy EA, Safran RJ, McGraw KJ. 2011Pterin-based ornamental coloration predicts yolk antioxidant levels in female striped plateau lizards (Sceloporus virgatus). J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 519-527. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01801.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tigreros N. 2013Linking nutrition and sexual selection across life stages in a model butterfly system. Funct. Ecol. 27, 145-154. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.12006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Abalos J, de Lanuza GP, Carazo P, Font E.. 2016The role of male coloration in the outcome of staged contests in the European common wall lizard (Podarcis muralis). Behaviour 153, 607-631. ( 10.1163/1568539X-00003366) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Merkling T, Chandrasoma D, Rankin KJ, Whiting MJ. 2018Seeing red: pteridine-based colour and male quality in a dragon lizard. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 124, 677-689. ( 10.1093/biolinnean/bly074) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abalos J, et al. 2020No evidence for differential sociosexual behavior and space use in the color morphs of the European common wall lizard (Podarcis muralis). Ecol. Evol. 10, 10 986-11 005. ( 10.1002/ece3.6659) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Grether GF, Cummings ME, Hudon, J. 2005Countergradient variation in the sexual coloration of guppies (Poecilia reticulata): drosopterin synthesis balances carotenoid availability. Evolution 59, 175-188. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb00904.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stuart-Fox D, Rankin K, Lutz A, Elliott A, Hugall AF, McLean CA, Medina I.. 2021Environmental gradients predict the ratio of environmentally acquired carotenoids to self-synthesised pteridine pigments. Ecol. Lett. 00, 1-12. ( 10.1111/ele.13850) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Béziers P, Ducrest AL, San-Jose LM, Simon C, Roulin, A. 2019Expression of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor genes co-varies with a stress-related colour signal in barn owls. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 283, 113224. ( 10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.113224) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cantarero A, Andrade P, Carneiro M, Moreno-Borrallo A, Alonso-Alvarez, C. 2020Testing the carotenoid-based sexual signalling mechanism by altering CYP2J19 gene expression and colour in a bird species. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201067. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.1067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Morgan TH. 1910Sex limited inheritance in Drosophila. Science 32, 120-122. ( 10.1126/science.32.812.120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ewart GD, Howells AJ. 1998ABC transporters involved in transport of eye pigment precursors in Drosophila melanogaster. Methods Enzymol. 292, 213-224. ( 10.1016/S0076-6879(98)92017-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lloyd V, Ramaswami M, Krämer, H. 1998Not just pretty eyes: Drosophila eye-colour mutations and lysosomal delivery. Trends Cell Biol., 8, 257-259. ( 10.1016/S0962-8924(98)01270-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Grant P, et al. 2016An eye on trafficking genes: identification of four eye color mutations in Drosophila. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 6, 3185-3196. ( 10.1534/g3.116.032508) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rong YS, Golic KG. 1998Dominant defects in Drosophila eye pigmentation resulting from a euchromatin–heterochromatin fusion gene. Genetics 150, 1551-1566. ( 10.1093/genetics/150.4.1551) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Dutton FL, Chovnick A. 1988Developmental regulation of the rosy locus in Drosophila melanogaster. In The molecular biology of cell determination and cell differentiation, vol. 5 (ed. LW Browder), pp. 267–316. Boston, MA: Springer. ( 10.1007/978-1-4615-6817-9_10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Watt WB. 1972Xanthine dehydrogenase and pteridine metabolism in Colias butterflies. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 1445-1451. ( 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)45578-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pimsler ML, Jackson JM, Lozier JD. 2017Population genomics reveals a candidate gene involved in bumble bee pigmentation. Ecol. Evol., 7, 3406-3413. ( 10.1002/ece3.2935) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yim JJ, Grell EH, Jacobson KB. 1977Mechanism of suppression in Drosophila: control of sepiapterin synthase at the purple locus. Science 198, 1168-1170. ( 10.1126/science.412253) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mackay WJ, O'Donnell JM. 1983A genetic analysis of the pteridine biosynthetic enzyme, guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase, in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 105, 35-53. ( 10.1093/genetics/105.1.35) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Switchenko AC, Primus JP, Brown GM. 1984Intermediates in the enzymic synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 120, 754-760. ( 10.1016/S0006-291X(84)80171-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Alcañiz S, Silva FJ. 1997Phenylalanine hydroxylase participation in the synthesis of serotonin and pteridines in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 116, 205-212. ( 10.1016/S0742-8413(96)00148-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Giordano E, Peluso I, Rendina R, Digilio A, Furia M. 2003The clot gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a conserved member of the thioredoxin-like protein superfamily. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268, 692-697. ( 10.1007/s00438-002-0792-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kim J, Park SI, Ahn C, Kim H, Yim J. 2009Guanine deaminase functions as dihydropterin deaminase in the biosynthesis of aurodrosopterin, a minor red eye pigment of Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23 426-23 435. ( 10.1074/jbc.M109.016493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kim K. 2018Structure-based analysis of Clot as a thioredoxin-related protein of 14 kDa in Drosophila via experimental and computational approaches. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 65, 338-345. ( 10.1002/bab.1624) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kim J, Suh H, Kim S, Kim K, Ahn C, Yim J. 2006Identification and characteristics of the structural gene for the Drosophila eye colour mutant sepia, encoding PDA synthase, a member of the omega class glutathione S-transferases. Biochem. J. 398, 451-460. ( 10.1042/BJ20060424) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Vargas-Lowman A, et al. 2019Cooption of the pteridine biosynthesis pathway underlies the diversification of embryonic colors in water striders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19 046-19 054. ( 10.1073/pnas.1908316116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Meng Y, et al. 2009The silkworm mutant lemon (lemon lethal) is a potential insect model for human sepiapterin reductase deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11 698-11 705. ( 10.1074/jbc.M900485200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fujii T, Abe H, Kawamoto M, Katsuma S, Banno Y, Shimada, T. 2013Albino (al) is a tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)-deficient mutant of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 594-600. ( 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.03.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tong X, et al. 2018Disruption of PTPS gene causing pale body color and lethal phenotype in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1024. ( 10.3390/ijms19041024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Woronik A, et al. 2019A transposable element insertion is associated with an alternative life history strategy. Nat. Commun. 10, 1-11. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13596-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Higashijima SI, Kojima T, Michiue T, Ishimaru S, Emori Y, Saigo K. 1992Dual Bar homeo box genes of Drosophila required in two photoreceptor cells, R1 and R6, and primary pigment cells for normal eye development. Genes Dev. 6, 50-60. ( 10.1101/gad.6.1.50) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ziegler I, McDonald T, Hesslinger C, Pelletier I, Boyle P. 2000Development of the pteridine pathway in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18 926-18 932. ( 10.1074/jbc.M910307199) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Odenthal J, et al. 1996Mutations affecting xanthophore pigmentation in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development 123, 391-398. ( 10.1242/dev.123.1.391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Parichy DM, Ransom DG, Paw B, Zon LI, Johnson SL. 2000An orthologue of the kit-related gene fms is required for development of neural crest-derived xanthophores and a subpopulation of adult melanocytes in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development 127, 3031-3044. ( 10.1242/dev.127.14.3031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.McMenamin SK, et al. 2014Thyroid hormone–dependent adult pigment cell lineage and pattern in zebrafish. Science 345, 1358-1361. ( 10.1126/science.1256251) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Minchin JE, Hughes SM. 2008Sequential actions of Pax3 and Pax7 drive xanthophore development in zebrafish neural crest. Dev. Biol. 317, 508-522. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Nagao Y, et al. 2018Distinct interactions of Sox5 and Sox10 in fate specification of pigment cells in medaka and zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007260. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007260) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ziegler, I. 2003The pteridine pathway in zebrafish: regulation and specification during the determination of neural crest cell-fate. Pigment Cell Res. 16, 172-182. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00044.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Andrade P, et al. 2019Regulatory changes in pterin and carotenoid genes underlie balanced color polymorphisms in the wall lizard. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5633-5642. ( 10.1073/pnas.1820320116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Andrade P, et al. 2021Molecular parallelisms between pigmentation in the avian iris and the integument of ectothermic vertebrates. PLoS Genet. e1009404. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009404) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Si S, Xu X, Zhuang Y, Luo SJ. 2020The genetics and evolution of eye color in domestic pigeons (Columba livia). BioRxiv. ( 10.1101/2020.10.25.340760) [DOI]

- 149.Maclary ET, et al. 2021Two genomic loci control three eye colors in the domestic pigeon (Columba livia). BioRxiv. ( 10.1101/2021.03.11.434326) [DOI]

- 150.Kimura T, et al. 2014Leucophores are similar to xanthophores in their specification and differentiation processes in medaka. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7343-7348. ( 10.1073/pnas.1311254111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ben J, Lim TM, Phang VP, Chan WK. 2003Cloning and tissue expression of 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase and xanthine dehydrogenase from Poecilia reticulata. Mar. Biotechnol. 5, 568-578. ( 10.1007/s10126-002-0121-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Li XM, et al. 2015Gene expression variations of red—white skin coloration in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 21 310-21 329. ( 10.3390/ijms160921310) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhang Y, et al. 2017Comparative transcriptome analysis of molecular mechanism underlying gray-to-red body color formation in red crucian carp (Carassius auratus, red var.). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 43, 1387-1398. ( 10.1007/s10695-017-0379-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Stuckert AM, Moore E, Coyle KP, Davison I, MacManes MD, Roberts R, Summers K. 2019Variation in pigmentation gene expression is associated with distinct aposematic color morphs in the poison frog Dendrobates auratus. BMC Evol. Biol. 19, 1-15. ( 10.1186/s12862-019-1410-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Rodríguez A, Mundy NI, Ibáñez R, Pröhl, H. 2020Being red, blue and green: the genetic basis of coloration differences in the strawberry poison frog (Oophaga pumilio). BMC Genomics 21, 1-16. ( 10.1186/s12864-019-6419-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.McLean CA, Lutz A, Rankin KJ, Stuart-Fox D, Moussalli, A. 2017Revealing the biochemical and genetic basis of color variation in a polymorphic lizard. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1924-1935. ( 10.1093/molbev/msx136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Jiang G, Song J, Hu H, Tong X, Dai, F. 2020Evaluation of the silkworm lemon mutant as an invertebrate animal model for human sepiapterin reductase deficiency. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 191888. ( 10.1098/rsos.191888) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Twyman H, Valenzuela N, Literman R, Andersson S, Mundy NI. 2016Seeing red to being red: conserved genetic mechanism for red cone oil droplets and co-option for red coloration in birds and turtles. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20161208. ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.1208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Deshmukh R, Baral S, Gandhimathi A, Kuwalekar M, Kunte, K. 2018Mimicry in butterflies: co-option and a bag of magnificent developmental genetic tricks. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Dev. Biol. 7, e291. ( 10.1002/wdev.291) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Okude G, Futahashi R. 2021Pigmentation and color pattern diversity in Odonata. Curr. Opin Genet. Dev. 69, 14-20. ( 10.1016/j.gde.2020.12.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Krajíček J, et al. 2014Capillary electrophoresis of pterin derivatives responsible for the warning coloration of Heteroptera. J. Chromatogr. A 1336, 94-100. ( 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.02.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Chen G, Ning B, Shi T. 2019Single-cell RNA-Seq technologies and related computational data analysis. Front. Genet. 10, 317. ( 10.3389/fgene.2019.00317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Zhuang X. 2021Spatially resolved single-cell genomics and transcriptomics by imaging. Nat. Methods 18, 18-22. ( 10.1038/s41592-020-01037-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Pott S, Lieb JD. 2015Single-cell ATAC-seq: strength in numbers. Genome Biol. 16, 1-4. ( 10.1186/s13059-015-0737-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]