Abstract

Objective

The objectives of this study were to investigate how families prepared children for the death of a significant adult, and how health and social care professionals provided psychosocial support to families about a relative’s death during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design/setting

A mixed methods design; an observational survey with health and social care professionals and relatives bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, and in-depth interviews with bereaved relatives and professionals were conducted. Data were analysed thematically.

Participants

A total of 623 participants completed the survey and interviews were conducted with 19 bereaved relatives and 16 professionals.

Results

Many children were not prepared for a death of an important adult during the pandemic. Obstacles to preparing children included families’ lack of understanding about their relative’s declining health; parental belief that not telling children was protecting them from becoming upset; and parents’ uncertainty about how best to prepare their children for the death. Only 10.2% (n=11) of relatives reported professionals asked them about their deceased relative’s relationships with children. This contrasts with 68.5% (n=72) of professionals who reported that the healthcare team asked about patient’s relationships with children. Professionals did not provide families with psychosocial support to facilitate preparation, and resources were less available or inappropriate for families during the pandemic. Three themes were identified: (1) obstacles to telling children a significant adult is going to die, (2) professionals’ role in helping families to prepare children for the death of a significant adult during the pandemic, and (3) how families prepare children for the death of a significant adult.

Conclusions

Professionals need to: provide clear and honest communication about a poor prognosis; start a conversation with families about the dying patient’s significant relationships with children; and reassure families that telling children someone close to them is dying is beneficial for their longer term psychological adjustment.

Keywords: COVID-19, palliative care, adult palliative care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First known study that has included quantitative measures about family-centred conversations in end-of-life care.

To promote study rigour, second interviews were conducted with some participants to provide clarity on their end-of-life experiences during the pandemic.

Findings are limited to an ethnically homogenous White population.

There is a risk of bias as participants were self-selected to this study and a survey was distributed online with open participation and without direct sampling.

Background

Families are often unsure how best to prepare children (<18 years old) for the death of someone involved in their lives.1 Literature reports that even when a death is expected the reality of a family member’s poor prognosis is not fully shared with children.2 3 Clear and honest communication with children about the declining health and impending death of a significant adult can promote psychosocial adjustment for children, including better mental and physical health outcomes and fewer referrals to psychiatric services.4 5

Parents within family groups have reported a desire and need for advice and guidance from health and social care professionals (HSCPs) about how, when and what they should tell children regarding an impending death.1 2 6 Despite the unique positioning of clinical services, families have highlighted a lack of supportive care from HSCPs about how to prepare and support children for a significant death.2 7 HSCPs have reported family-centred conversations as an emotionally challenging aspect of their clinical role, often perceiving this to be the role of other healthcare colleagues.8–10

Provisions of family-centred care in clinical practice is likely to have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, including the increased practical and emotional pressures encountered by HSCPs,11 12 and the absence of families visiting in hospital, care home and hospice settings. Exploration of bereaved relatives’ and HSCPs’ experiences and perceptions will aid our understanding of how families navigated preparing children for a death during the COVID-19 crisis. This will help inform current and future clinical practice on how families can be better supported as they prepare children for a bereavement.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to explore how families prepared children for a death during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. The objectives were to investigate:

How families navigated telling children someone close to them was going to die.

Professionals’ role in supporting families as they prepared children for a death.

Methods

Design and context

A mixed methods design was used for this study13; (1) relatives bereaved during the pandemic and HSCPs who provided end-of-life care during the same period completed an observational, open online survey, and (2) survey respondents who expressed an interest to provide further information were invited, via email, and participated in an in-depth qualitative interview regarding their experiences.

This study was embedded within a national quantitative UK survey which aimed to: (1) explore the experiences of bereaved relatives regarding end-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) understand the impact of COVID-19 on the bereavement process for relatives, and (3) explore the experiences of HSCPs who provided end-of-life care during the COVID-19 crisis. Other findings from this research have been published elsewhere.11 12 14

Patient and public involvement

Five members from the online advisory panel of the Clinical Research and Innovation Office at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, and the lead patient and public involvement (PPI) representative from the Clinical Cancer Trials Executive Committee provided input to survey development. PPI involvement was helpful for ensuring the language/questioning was appropriate, and resulted in revisions, such as the inclusion of additional response criteria, such as adding ‘don’t know’.

Participants

Bereaved relatives

Participants were considered eligible to complete the survey if they were ≥18 years old, experienced the death of a family member or close friend during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March to June 2020) and resided in the UK. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria to the cause of the death. Of the 48 respondents who expressed an interest to be involved in follow-up research, a total of 19 relatives were interviewed; 28 potential participants did not respond to the interview invitation, and one declined.

Health and social care professionals

HSCPs were considered eligible to take part in the survey if they provided end-of-life care during the first wave (March to June 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. For simplicity, the term ‘HSCP’ is used as a collective term to describe the range of professionals and individuals involved in end-of-life care and support. Seventy-eight respondents expressed an interest to be involved in follow-up research. Of these, 16 took part in a qualitative interview; 60 did not respond to the invitation, and two replied stating they were no longer interested.

Data collection

An online survey was developed using the Qualtrics platform. Initially, respondents were asked to select if they were a bereaved friend/relative or an HSCP. The survey included questions about support for families in relation to preparing children for a death during the COVID-19 pandemic; questions were developed by the research team and were different for relatives and professionals (see online supplemental file). Appropriate demographic questions were asked, including age, gender and ethnicity, and relationship to the deceased or clinical role. The survey was promoted through social media platforms; public and charitable organisations related to palliative care and bereavement; and organisations of minoritised groups between June and September 2020.

bmjopen-2021-053099supp001.pdf (51.7KB, pdf)

Semistructured interviews were carried out between July and December 2020. Topic guides (box 1) were developed, informed by the literature, the study’s aims and objectives, and the research team who have a wealth of research and clinical experience in end-of-life and bereavement care. Interviews were conducted by two female researchers, neither of whom had prior relationships with the participants. Interviews were conducted on Zoom (n=9) or telephone (n=26), audio recorded and lasted between 20 and 98 min.

Box 1. Semistructured topic guide used to guide the conduct of the study.

Initial topics based on the literature and study aims and objectives

Exploration of end-of-life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exploration of how relatives managed the final weeks and days of life with their dependent children.

Exploration of the needs of families as they prepared children for a death during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exploration of professionals’ perceptions of the needs of families as they prepared children for death during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exploration of professionals’ perceptions of the psychosocial needs of families when a relative was dying during the pandemic in relation to their children.

Sample of additional topics for follow-up interviews

Professionals’ role in providing psychological support to families at end of life about important relationships with dependent children.

Professionals’ role in signposting families to family support services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Families’ engagement with family support services when a relative was at end of life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Children’s involvement in the family when a relative was at end of life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim after all interviews were completed and verified by the research team. Preliminary analysis identified some of the categories developed from the transcript data required further clarification. Following discussion as a research team and a protocol/ethical amendment, JRH invited eight participants via email to take part in a second interview to provide clarity on their experiences. Four bereaved relatives and two HSCPs agreed to another interview. Two bereaved relatives declined the invitation due to a lack of interest to take part in further studies. The topic guide was iteratively modified by the authors who are experienced clinicians and researchers in family-centred care (box 1). Second interviews were conducted by JRH (an experienced qualitative researcher) on Zoom, April 2021, audio recorded and lasted between 16 and 31 min.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics within SPSS V.26 by JRH and BM. The qualitative data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis by JRH.15 JRH read and re-read the transcripts to gain a sense of each participant’s story; manually coded the data by marking similar phrases or words from participant’s narratives; and identified where some of them constructed into themes, in combination with the quantitative data. This approach was undertaken to enhance and illustrate study findings.16 ER and LJD independently reviewed the data resulting in the inclusion of one theme and renaming of two subthemes. Themes were refined through critical dialogue with all authors.

Ethical considerations

Respondents opted into the study and were provided with written information about the research and provided consent prior to participation. Participants were not forced to answer the questions within the survey and each question was optional. Respondents were only contacted to take part in interviews if they expressed an interest to be invited to provide further information. Oral consent was also collected at time of interview. Participants were aware of their right to pause, reschedule or terminate the interview. Data protection procedures were observed, and assurances of confidentiality were provided.

Results

Quantitative survey participants

A total of 278 UK-based bereaved relatives (216 female, 59 male, 3 other) completed the survey. The mean age of respondents was 53.4 years (range 19–87 years), and with a single exception, all were from a White British ethnic group. The respondents’ relationship with the deceased included son/daughter (n=174), spouse/partner (n=22), parent (n=4), son/daughter in-law (n=12), niece/nephew (n=13), grandchild (n=19), sibling (n=6), friend (n=14) and other (n=14). The age of the deceased ranged from 22 to 103 years (mAvgAge=81.6 years, SD 12.2). Most of the deaths took place in England (n=179). Of the 278 bereaved relatives, 110 reported their relative/friend ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ had coronavirus (table 1). In total, 345 HSCPs completed the survey, which included nurses (n=155), doctors (n=114), allied health professionals (n=28), social care professionals (n=2), volunteers (n=5) and healthcare assistants (n=23). Eighteen professionals did not provide details about their role. Sample characteristics are reported in table 2.

Table 1.

Survey responses from bereaved relatives

| Total responders | Yes, certainly (%) | Yes, probably (%) | No, probably not (%) | No, certainly not (%) | |

| Q. Was the person who died infected with coronavirus? | 256 | 82 (32) | 28 (11) | 54 (21.1) | 92 (35.9) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the bereaved relatives and HSCPs who completed the survey

| Characteristics of HSCPs surveyed | n | Characteristics of bereaved relatives surveyed | n |

| Professional role | Gender of participant | ||

| Doctor | 114 | Female | 216 |

| Nurse | 155 | Male | 59 |

| Pharmacist | 1 | Non-binary | 1 |

| Physiotherapist | 13 | Other | 1 |

| Occupational therapist | 2 | Missing | 1 |

| Chaplain | 5 | ||

| Speech and language therapist | 4 | Participant’s relationship to the family member who died | |

| Dietician | 1 | Son/daughter | 174 |

| Social care professional | 2 | Spouse/partner | 22 |

| Healthcare assistant | 23 | Parent | 4 |

| Volunteer | 5 | Son/daughter-in-law | 12 |

| Other (no details/free text provided) | 13 | Niece/nephew | 13 |

| Missing | 5 | Grandchild | 19 |

| Sibling | 6 | ||

| Location of professional | Friend | 14 | |

| England | 247 | Other | 14 |

| Scotland | 58 | ||

| Wales | 7 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 25 | Location of death | |

| Missing | 8 | England | 179 |

| Scotland | 63 | ||

| Wales | 10 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 7 | ||

| Missing | 19 | ||

| Place of death | |||

| Hospital | 75 | ||

| General ward (n=34) | |||

| Intensive care unit (n=13) | |||

| Coronavirus ward (n=26) | |||

| Other (n=2) | |||

| Usual place of care | 192 | ||

| Home (n=30) | |||

| Care home (n=162) | |||

| Hospice | 10 | ||

| Missing | 1 | ||

| Was the person who died infected with coronavirus? | |||

| Yes, certainly | 82 | ||

| Yes, probably | 28 | ||

| No, probably not | 54 | ||

| No, certainly not | 92 | ||

| Missing | 22 |

HSCP, health and social care professional.

Qualitative interview participants

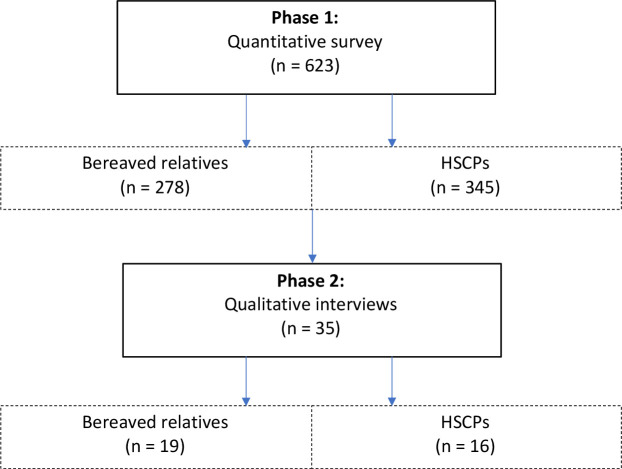

Overall, 19 relatives (12 female, 7 male) and 16 HSCPs (11 female, 5 male) were interviewed. The participant’s relationship with their family member varied, including spouse/partner (n=4); son/daughter-in-law (n=2); adult child (n=11); grandchild (n=1); and niece (n=1). Most relatives (n=16) reported the deceased had significant relationships with children (<18 years old), including parent (n=2), grandparent (n=14) and aunt/uncle (n=3). The deceased were aged 50–59 years (n=1), 60–69 years (n=3), 70–79 years (n=3), 80–89 years (n=9) or 90 years and over (n=3). A range of HSCPs were involved, including registered nurses (n=4); clinical nurse specialists (n=3); team leaders (nurse) (n=2); medical consultants (n=2); junior doctors (n=2), as well as a social worker; chaplain; and healthcare assistant. Additional sample characteristics are reported in table 3. A summary of the participants involved in the quantitative and qualitative phases of this study is shown in figure 1.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the bereaved relatives and HSCPs interviewed in the study

| Characteristics of HSCPs interviewed | n | Characteristics of bereaved relatives interviewed | n |

| Hospital-based professionals | 1 | Gender of participant | |

| Palliative care social worker | 1 | Female | 12 |

| Palliative care consultant | 2 | Male | 7 |

| Palliative care clinical nurse specialist | 1 | ||

| Palliative care team leader (nurse) | 1 | Participant’s relationship to the family member who died | |

| Registered nurse | 1 | Spouse/partner | 4 |

| Healthcare chaplain | 1 | Adult child | 11 |

| Healthcare assistant | 2 | Adult grandchild | 1 |

| Junior doctor | 2 | Son/daughter-in-law | 2 |

| Niece | 1 | ||

| Care home-based professionals | |||

| Registered nurse | 2 | Ethnicity of relative/deceased | |

| Palliative care registered nurse | 1 | White (English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British) | 19 |

| Hospice-based professionals | Location of relative/death | ||

| Palliative care clinical nurse specialist | 1 | England | 14 |

| Palliative care consultant | 1 | Scotland | 4 |

| Palliative care nurse | 1 | Wales | 1 |

| Northern Ireland | 0 | ||

| Location of professional | |||

| England | 8 | Place of death | |

| Scotland | 5 | Hospital | 10 |

| Wales | 2 | General ward (n=3) | |

| Northern Ireland | 1 | Intensive care unit (n=4) | |

| Coronavirus ward (n=3) | |||

| Gender of professional | Care home | 9 | |

| Female | 11 | ||

| Male | 5 | Chronic condition of deceased family member | |

| Dementia | 8 | ||

| Ethnicity of professional | Cancer | 4 | |

| White (English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British) | 16 | Heart failure | 3 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 2 | ||

| Renal disease | 1 | ||

| None identified | 1 | ||

| Age of participant | |||

| 20–29 | 1 | ||

| 30–39 | 2 | ||

| 40–49 | 1 | ||

| 50–59 | 8 | ||

| 60–69 | 6 | ||

| 70–79 | 1 | ||

| Age of family member who died | |||

| 50–59 | 1 | ||

| 60–69 | 2 | ||

| 70–79 | 2 | ||

| 80–89 | 9 | ||

| 90+ | 3 | ||

| Age of the children | |||

| 0–11 years old | 15 | ||

| 12–18 years old | 9 |

HSCP, health and social care professional.

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the participants involved in the quantitative and qualitative phases of this study. In phase 1, a total of 623 respondents completed the quantitative survey, comprising 278 bereaved relatives and 345 health and social care professionals (HSCPs). In phase 2, thirty-five qualitative interviews were conducted, of which 19 were bereaved relatives and 16 were HSCPs.

The data below describe relatives’ and HSCPs’ experiences and perceptions of the final weeks and days of life. Of the participants interviewed, relatives reported their dying family member was receiving care at a care home (n=9) or hospital (n=10) at end of life. Additionally, most relatives interviewed reported their dying family member was living with a chronic illness, and at a point during the pandemic their health condition had rapidly deteriorated; most also tested positive for COVID-19 (n=13). HSCPs interviewed worked in acute (n=10) and community (n=6) settings. Data are discussed under three themes: (1) obstacles to telling the children a significant adult is going to die, (2) HSCPs’ role in helping families to prepare children for the death of a significant adult during the pandemic, and (3) how families prepare children for the death of a significant adult.

Theme 1: obstacles to telling children a significant adult is going to die

Where a significant adult had a poor prognosis, some relatives and HSCPs reported children had been informed and regularly updated by their parents about the declining health and impending death. In other families, children were reported by relatives and professionals as less prepared for the death. These issues are further discussed under two subthemes: (1) parental belief that not telling children was protecting their children from distress, and (2) the family’s lack of understanding about the decline in their loved one’s health.

Subtheme 1: parental belief that not telling children was protecting their children from distress

Relatives and professionals reflected that parents within the family network were unsure how they could tell their children that a significant adult was going to die or what age-appropriate language to use. Additionally, relatives reported that the children’s parents were concerned about how children would react to the news. More often, relatives felt it was better not to tell the children about the seriousness of the family member’s condition in order to protect them from becoming upset.

I don’t think they [referring to adult children] mentioned it then through his illness really. They weren’t mentioning it on a daily basis or anything. They didn’t think it was right to tell them [referring to dependent children] that their granda wasn’t going to make it. I just think they didn’t want to make them sad at that time. (Bereaved relative; spouse of the deceased; hospital-based death; first interview)

Although most relatives reported an awareness that their family member’s death was expected within weeks or days, it often seemed that the children continued to be less informed of the situation. On occasions, young children (<12 years old) in the family asked their parents to see (physically or virtually) their dying family member. At times, parents told their children ‘you can’t visit granny because of the virus but you hopefully will see her soon’ or ‘grandpa is very sick today but maybe tomorrow he will be better, and you can talk to him then’. Relatives and professionals considered this deliberate strategy was an attempt by parents to protect their children from distress.

Subtheme 2: the family’s lack of understanding about the decline in their loved one’s health

Some families reported an absence of clear information from HSCPs about their family member’s condition at end of life; consequently, adult family members reflected that they themselves were unprepared for the death. On occasions, relatives felt they were provided with ‘false hope’ regarding their family member’s condition when healthcare teams used phrases such as ‘there has been no change and your mum is comfortable’ or ‘things are just the same and he is doing okay’. Consequently, relatives stated that parents within the family network were not aware of the severity of the situation, resulting in parental uncertainty about whether or how to share this information with their children. Relatives reflected it would have been helpful if HSCPs had used clear language such as ‘dying’ and ‘end of life’ when describing the patient’s condition to the family.

Mum went into the hospital on the Friday around midnight and died on Sunday. I was ringing the hospital every few hours and they just kept saying ‘she’s still the same and she’s comfortable’. We took that as good news that she was doing okay. And that’s what we told the girls. That was all we knew, until I got the call on Sunday morning telling me to get to hospital right away as mum only had a few hours to live. (Bereaved relative; adult children of the deceased; hospital death; second interview)

Theme 2: HSCPs’ role in helping families to prepare children for a significant death during the pandemic

Professionals provided varying amounts of psychosocial support to families during the pandemic, but on many occasions specific support in preparing children for a death was not offered. These issues are discussed under two subthemes: (1) a lack of family-centred conversations, and (2) psychosocial support provided to families with children during the pandemic.

Subtheme 1: a lack of family-centred conversations during the pandemic

Of 105 responders, 68.5% (n=72) of HSCPs reported that the healthcare team ‘probably’ or ‘definitely’ asked relatives if the dying patient had important relationships with children (table 4). This contrasts with reports from 108 bereaved relatives, of which only 10.2% (n=11) reported that HSCPs asked if the dying family member had important relationships with children (table 5).

Table 4.

Survey responses from HSCPs

| Total responders | Yes, definitely (%) | Yes, probably (%) | No, probably not (%) | No, definitely not (%) | I don’t know (%) | |

| Q. Did the healthcare team ask whether the patient had important relationships with children or young adults (aged 0–18 years)? | 105 | 39 (37.1) | 33 (31.4) | 7 (6.7) | 7 (6.7) | 19 (18.1) |

HSCP, health and social care professional.

Table 5.

Survey responses from bereaved relatives

| Total responders | Yes (%) | No (%) | |

| Q. Did anyone in the healthcare team ask if your relative/friend had any important relationships with children (aged 0–18 years old)? | 108 | 11 (10.2) | 97 (89.8) |

Often, relatives perceived that healthcare teams were ‘too busy’ during the pandemic to provide family-centred support. Some relatives felt professionals would not have thought to ask if the dying patient had important relationships with children, as they were not of a typical age to have dependent children.

Nobody asked me if I had children. I suppose they didn’t think to ask as my mother was 92 and I’m 67. It’s not something that I directly needed, but for my son that would have helped him and my daughter in-law. But at the same time, I don’t think the NHS staff had time for these things. (Bereaved relative; adult child of the deceased; hospital-based death; first interview)

HSCPs described increased pressures during the pandemic such as reduced staffing levels from sickness and increased workloads. Consequently, care was centred on clinical elements such as pain and symptom management. However, most professionals reflected that these obstacles to family-centred conversations predated the pandemic. On occasions, HSCPs felt the pandemic meant there was ‘less of a need to prioritise conversations about the children’ with relatives, as they perceived it would have been ‘easier’ for parents to talk to their children about a death due to increased general conversations and media coverage about dying.

It’s not really my role. And I’m not sure that that ever, if I’m honest is ever, that’s not really been part of what I do. It’s probably easier now with all that’s been going on over the last year. (HSCP; palliative care registered nurse; care home based; first interview)

Subtheme 2: psychosocial support provided to families with children during the pandemic

Respondents were asked to assess the overall level of support given by the healthcare team to relatives or friends about talking to children about a patient’s illness. Of the 65 HSCPs, 32.3% (n=21) felt the level of support provided to relatives by healthcare teams regarding talking to children about the patient’s impending death was ‘excellent/good’, while 52.3% (n=34) reported ‘I don’t know’ to the same question (table 6). This contrasted with the responses from 75 bereaved relatives; 52% (n=39) ‘disagreed/strongly disagreed’ that they had received enough support from HSCPs about talking to children about the impending death. Only 17.3% (n=13) of bereaved relatives agreed/strongly agreed they had received adequate support from professionals (table 7).

Table 6.

Survey responses from HSCPs

| Total responders | Excellent (%) | Good (%) | Fair (%) | Poor (%) | I don’t know (%) | |

| Q. How would you assess the overall level of support given by the healthcare team to relatives/friends about talking to children about a patient’s illness? | 65 | 11 (16.9) | 10 (15.4) | 6 (9.2) | 4 (6.2) | 34 (52.3) |

HSCP, health and social care professional.

Table 7.

Survey responses from bereaved relatives

| Total responders | Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Neither agree nor disagree (%) | Disagree (%) |

Strongly disagree (%) | |

| Q. I was given enough help and support by the healthcare team to talk to children about my relative/friend’s illness. | 75 | 9 (12) | 4 (5.3) | 23 (30.7) | 19 (25.3) | 20 (26.7) |

Due to restricted visiting to hospital, care home and hospice settings during the pandemic, some of the relatives and HSCPs interviewed reported that families had video calls with their dying family member when their health permitted. From these interviews, it appeared that HSCPs had an instrumental role in encouraging parents to involve children in virtual calls. Some HSCPs believed it was important to include the children in virtual calls so they would feel part of the dying experience and help them understand the death. However, it seemed these virtual connections between dying family members and their relatives rarely happened, and where they did occur, children were only included if they had already been informed of the reality of the situation. Some professionals reflected this as a ‘positive outcome for children in the pandemic’, as prepandemic children were usually not involved when a significant adult was in the final weeks and days of life in hospital and care home settings.

We’re really quite keen on involving children as much as possible. But there had to be more thinking outside the box. We had in fact we even managed to facilitate a video between a dying mum and her children on one of our wards you know right at the height of COVID. (HSCP; palliative care social worker; hospital based; first interview)

Where children were identified in the family, HSCPs often felt they lacked adequate knowledge to provide meaningful support in the ‘here and now’ and consequently signposted relatives to the websites of charities that provide family support or advice. Many HSCPs believed psychosocial support to families regarding children was provided by other colleagues, such as social care professionals or registered nurses on the wards or in the community.

I didn’t know what else I could have done in that moment. I think [charity name] are quite good with this sort of thing when it comes to illness and children. (HSCP; palliative care clinical nurse specialist; hospital based; first interview)

Theme 3: how families prepare children for the death of a significant adult

On occasions, parents reported that the websites to which they had been signposted by HSCPs were no longer available as the charity had ceased operations during the pandemic. Parents frequently reported that online information did not meet the developmental or cognitive needs of their children. Some parents searched the internet for guidance on how best to share this information with their adolescent children (aged 13+) but felt the information they found online was centred on talking about death with younger children.

I was searching the Internet for the words. But anything I came across was all quite childish. It was for young children really. It wasn’t helpful for us to talk to my [teenage child]. (Bereaved relative; niece of the deceased; care home death; first interview)

More often, relatives reflected it would have been helpful if they had ‘someone to talk to’ about how best to tell their children of the impending death rather than accessing websites. Some relatives attempted to contact services that provide support to family on preparing children for a death. However, many found it challenging as the staff from these organisations were furloughed during the pandemic. A number of relatives reported their loved one had already died by the time a family support worker got in contact with them.

I got in touch with [organisation name] and they said the lady working in family support was only working 2 days a week because of the coronavirus, so would get back in touch with me when back in the office on Friday. But mum died on the Thursday, so it was too late. (Bereaved relative; adult child of the deceased; hospital death; second interview)

While some parents did tell their children the significant adult was going to ‘die’, others informed their young children using phrases such as ‘grandpa is going heaven soon’ or ‘granny is going to the stars soon’. It seemed parents struggled to tell the children when a significant adult had died, preferring to use euphemisms such as ‘passed-away’ or ‘star in the sky’. Most relatives reflected it would have been ‘easier’ for the parents to tell the children of the death if HSCPs had provided advice and guidance on how to tell children a significant adult was going to die before this happened.

I just wanted somebody to tell me how to start the conversation with them [the children] that granny was going to die. That’s what was missing. I didn’t want or need a perfect script, but some pointers on how to do it would have gone a long way. (Bereaved relative; adult child of the deceased; hospital death; second interview)

Discussion

There appears to be a striking mismatch between reports from HSCPs and relatives bereaved during the COVID-19 crisis about whether professionals had asked if patients had important relationships with children. The majority of participating HSCPs indicated that the team had ‘probably’ or ‘definitely asked’, whereas only 10.2% (n=11) of relatives stated this had occurred. This disparity was also reflected in the HSCPs and families’ ratings of the perceived level of support about talking to children. Most HSCPs in this study were not aware if families had been offered support, and the majority of relatives stated that they had not been provided with advice or guidance from professionals in telling children about an anticipated death. These inconsistencies between professionals and relatives may reflect HSCPs’ belief that the identification of children and family support falls within the remit of another member of the clinical team, but in practice this does not occur.9 10

Many children were not prepared for the death of a significant adult during the pandemic. Factors impacting this non-disclosure included adults’ own lack of understanding about the declining health and impending death of their loved one, and parental belief that not telling the children someone close to them was going to die was protecting them from distress. Similar findings have been reported in the literature.1 2 8 17 Psychoeducational resources were less available to families during the pandemic and were sometimes perceived to be inappropriate for the child’s age. Consequently, many children were not told the truth about their family member’s health in their final weeks and days of life; when the death happened, parents continued to struggle to share this news with their children.

Professionals felt they had insufficient time to engage in meaningful conversations with families about talking to children about illness and death during the COVID-19 crisis. A similar finding has been reported in the prepandemic literature.8–10 While acknowledging the multiple demands on HSCPs, particularly during a pandemic, the perceived lack of time for these conversations could be a form of avoidance, by which staff consciously or unconsciously protect themselves from this sensitive and emotionally demanding work.18

Some families were unsure how to tell their children someone in their life was going to die using age-appropriate language. It seems there is a lack of resources available to aid HSCPs’ ability to equip families with the necessary tools to have important conversations about death and dying with their children.9 Parents wanted time with HSCPs to discuss the language they might use with their children to prepare and support them for a bereavement, rather than relying on written materials or websites.

Despite the perception held by many HSCPs, conversations about death and dying with children did not seem to be ‘easier’ for parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. While general conversations about death have increased during the pandemic, the experience of raising this topic with children may be different when someone in their own family is nearing end of life.19 It is important that HSCPs do not make assumptions that families understand the reality of a relative’s declining health or realise how important it is to have honest conversations with children about illness and death.

Bereaved families have reflected it would have been helpful if HSCPs had started a conversation with them on how best to tell the children someone close to them was going to die.2 This would require HSCP to: (1) understand the long-term benefits of effective communication for children’s psychological well-being and family functioning; and (2) identify children within a patient’s family and social network. HSCPs should ask their patients and/or the relatives ‘do you have important relationships with children?’. This question should be universal and not based on a patient’s age. While most of the patients in this study were later in life, the number of relationships an adult has with children is likely to increase with each successive generation. Additionally, the proportion of grandparents who provide formal or informal childcare for working parents means this population is significantly involved in the lives of children.20 Crucially, when relationships with children are identified, HSCPs must have the training and resources needed to follow-up with adults about why talking to children matters and how these conversations can be initiated with children of all ages.

This is the first known study that has included quantitative measures about family-centred conversations in end-of-life care. It is possible that bereaved relatives did not answer the survey questions about the children as this may not have been reflective of their family set-up. This research was embedded in a national survey of end-of-life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and some of the bereaved relatives interviewed did not have important relationships with children; however, it was considered ethically appropriate in the Methods section to report the total number of interviews conducted. Findings are limited to an ethnically homogenous White population; future studies should investigate the experiences of preparing children for death from ethnic minority populations. Participants were self-selected to the survey which can lead to an unrepresentative sample of the overall population included.

Conclusion

There was a pronounced difference between bereaved relatives’ and HSCPs’ perceptions about identifying children affected by the anticipated death of an important adult during the COVID-19 pandemic. HSCPs have an important role in supporting families to initiate conversations with children about end of life in a timely and developmentally sensitive manner. This is essential for the long-term psychological well-being of bereaved families and children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks and gratitude to the bereaved relatives and professionals who participated in this study. The authors extend their thanks to Rosemary Hughes and Tamsin McGlinchey for conducting the interviews.

Footnotes

Twitter: @CattyRM

Contributors: Five authors were involved in the design of this study, survey dissemination and data collection (CRM, SM, LJD, ER, JRH). First interviews were conducted by two female researchers at the University of Liverpool. Second interviews were conducted by JRH. JRH analysed and interpreted the data. BM supported the quantitative analysis. JRH, ER and LJD drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. JRH took responsibility for the submission process. JRH and ER are joint first authors of this paper.

Funding: Data analysis and manuscript preparation were supported by funding from the Westminster Foundation awarded to University of Oxford.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that supports the findings of this study are available at the University of Oxford, University of Liverpool, and University of Sheffield’s repositories and available on request from the second author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Liverpool Central University Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 7761).

References

- 1.Hanna JR, McCaughan E, Semple CJ. Challenges and support needs of parents and children when a parent is at end of life: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2019;33:1017–44. 10.1177/0269216319857622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semple CJ, McCaughan E, Beck ER, et al. 'Living in parallel worlds' - bereaved parents' experience of family life when a parent with dependent children is at end of life from cancer: A qualitative study. Palliat Med 2021;35:933–42. 10.1177/02692163211001719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall S, Fearnley R, Bristowe K, et al. The perspectives of children and young people affected by parental life-limiting illness: an integrative review and thematic synthesis. Palliat Med 2021;35:246–60. 10.1177/0269216320967590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalton L, Rapa E, Ziebland S, et al. Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition in their parent. The Lancet 2019;393:1164–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33202-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis J, Dowrick C, Lloyd-Williams M. The long-term impact of early parental death: lessons from a narrative study. J R Soc Med 2013;106:57–67. 10.1177/0141076812472623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearnley R, Boland JW. Communication and support from health-care professionals to families, with dependent children, following the diagnosis of parental life-limiting illness: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:212–22. 10.1177/0269216316655736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCaughan E, Semple CJ, Hanna JR. ‘Don’t forget the children’: a qualitative study when a parent is at end of life from cancer. Support Care Cancer 2021;31. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06341-3. [Epub ahead of print: 18 Jun 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalton LJ, McNivan A, Hanna JR. Family centred communication when an adult patient is diagnosed with a life-threatening condition 2021.

- 9.Hanna JR, McCaughan E, Beck ER, et al. Providing care to parents dying from cancer with dependent children: health and social care professionals' experience. Psychooncology 2021;30:331–9. 10.1002/pon.5581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin P, Arber A, Reed L, et al. Health and social care professionals' experiences of supporting parents and their dependent children during, and following, the death of a parent: a qualitative review and thematic synthesis. Palliat Med 2019;33:49–65. 10.1177/0269216318803494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna JR, Rapa E, Dalton LJ, et al. A qualitative study of bereaved relatives' end of life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med 2021;35:843–51. 10.1177/02692163211004210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna JR, Rapa E, Dalton LJ, et al. Health and social care professionals' experiences of providing end of life care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2021;35:1249–57. 10.1177/02692163211017808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creswell JW, Tashakkori A. Editorial: developing Publishable mixed methods manuscripts. J Mix Methods Res 2007;1:107–11. 10.1177/1558689806298644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayland CR, Hughes R, Lane S, et al. Are public health measures and individualised care compatible in the face of a pandemic? a national observational study of bereaved relatives' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med 2021:2692163211019885. 10.1177/02692163211019885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019;11:589–97. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walshe C. Mixed method research in palliative care. In: MacLeod R, Van den Block L, eds. Textbook of palliative care. Springer, Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy VL, Lloyd-Williams M. Information and communication when a parent has advanced cancer. J Affect Disord 2009;114:149–55. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geerse OP, Lamas DJ, Sanders JJ, et al. A qualitative study of serious illness conversations in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2019;22:773–81. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caughlin JP, Mikucki-Enyart SL, Middleton AV, et al. Being open without talking about it: a rhetorical/normative approach to understanding topic avoidance in families after a lung cancer diagnosis. Commun Monogr 2011;78:409–36. 10.1080/03637751.2011.618141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchanan A, Rotkirch A. Twenty-First century grandparents: global perspectives on changing roles and consequences. Contemp Soc Sci 2018;13:131–44. 10.1080/21582041.2018.1467034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053099supp001.pdf (51.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that supports the findings of this study are available at the University of Oxford, University of Liverpool, and University of Sheffield’s repositories and available on request from the second author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.