Abstract

Objective

Adverse birth outcomes, which include stillbirth, preterm birth, low birthweight, congenital abnormalities, and stillbirth, are the leading cause of neonatal and infant mortality worldwide. We assessed adverse birth outcomes and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in Bale zone hospitals, Oromia, Southeast Ethiopia.

Methods

We used systematic random sampling in this cross-sectional study. We identified factors associated with adverse birth outcomes using bivariate analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Results

The proportion of adverse birth outcomes among participants was 21%. Of 576 births, 70 (12.2%) were low birthweight, 49 (8.5%) were preterm birth, 45 (7.8%) were stillbirth, and 18 (3.1%) infants had congenital anomalies. Inadequate antenatal care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 6.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.25–13.32), multiple pregnancy (AOR = 4.74, 95% CI 1.55–14.45), premature rupture of membranes in the current pregnancy (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.21), hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL (AOR = 3.22, 95% CI 1.85–5.58), and mid-upper arm circumference less than 23 cm (AOR = 5.93, 95% CI 3.49–10.08) were all significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes.

Conclusions

Approximately one in five study participants had adverse birth outcomes. Increasing antenatal care uptake, ferrous supplementation during pregnancy, and improving the quality of maternal health services are recommended.

Keywords: Preterm, stillbirth, low birthweight, congenital anomaly, adverse birth outcome, risk factor

Introduction

Birth outcomes are not always favorable and adverse birth outcomes can occur in both mothers and infants.1 Reported adverse birth outcomes include stillbirth, preterm birth, low birthweight, and congenital abnormalities.2,3 These outcomes are the main cause of neonatal and infant mortality worldwide.4,5

Globally, adverse birth outcomes affect millions of newborns. Preterm birth contributes to one million neonatal deaths annually.6–8 An estimated 15 million infants worldwide are born before 37 weeks of gestation annually. More than 60% of preterm births occur in Africa and South Asia.9 Low birthweight (LBW) continues to be a serious public health problem globally that is estimated to account for 15% to 20% of all births worldwide,10 with most of these deaths occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa.5,11

The burden of adverse birth outcomes is high in Ethiopia.12 Approximately 320,000 babies are born before 37 weeks of gestation each year.6,13 In 2014, there were 27,243 deaths owing to LBW, accounting for 4.53% of total deaths.14 According to recent studies conducted in different parts of the country, the prevalence of adverse birth outcomes in Ethiopia ranges from 18.2% to 32.5%.15–18 The most frequently identified types of adverse birth outcome are LBW and stillbirth.15,16

A number of studies have shown that induced onset of labor, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), previous poor obstetric history, multiple pregnancies, multigravida, inadequate antenatal care (ANC), hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL, rural residence, and malaria infection during pregnancy are significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes.15–19

Despite some studies having described various forms of adverse birth outcome in some parts of Ethiopia, there is limited information on the incidence of adverse birth outcomes and the associated factors in the Bale zone. Most studies have been conducted in the northern and southern parts of the country15–21 and are not representative of populations that are mostly pastoralist. Pastoralist women have low ANC follow-up because of their mobile lifestyle.22 Additionally, the Bale zone is geographically different from northern and southern Ethiopia. Hence, this study aimed to assess the magnitude and associated factors of adverse birth outcomes among mothers who give birth in Bale zone hospitals.

Methods

Study setting, design and population

We conducted an institutionally-based cross-sectional study in Bale zone hospitals, namely, Goba Referral Hospital, Robe District Hospital, Ginnir District Hospital, and Delomenna District Hospital. All hospitals in the Bale zone provide nearly all types of obstetric care. Goba Referral Hospital is the only referral hospital in the Bale zone that serves as a teaching hospital for medical and health sciences. The hospital also provides treatment and preventive services for approximately 1,836,907 people in the catchment area. Bale is the second largest zone in Oromia Regional State and is located 430 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. According to a report from the zonal health office, there were 44,962 births in 2010. Based on the Bale zone health office reports, the zone includes 717 health facilities (4 hospitals, 84 functional health centers, 351 functional health posts, 179 private clinics, and 95 pharmacy/drug shops).

All mothers who had normal births or adverse birth outcomes at Bale zone hospitals were the source population and all mothers who gave birth during the study period comprised the study population.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

We determined the sample size using a single population proportion formula, with the assumption of 95% confidence level (Z α/2 1.96, z value at α = 0.05), Pr (estimated proportion of adverse birth outcomes) of 32.5% which was taken from a previous study conducted at Dessie Referral Hospital (Northeast Ethiopia),15 and d (margin of error) of 0.04. Considering a 10% nonresponse rate, the final sample size was 580.

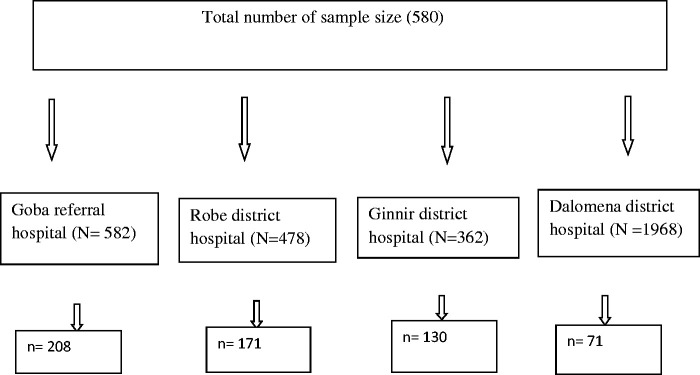

All hospitals in the Bale zone were included. Based on the number of deliveries in the 2 months prior to data collection for each hospital (Goba Referral Hospital and Robe, Ginnir, and Delomenna district hospitals), the total sample size was allocated proportionally among the hospitals (Figure 1). We used a systematic random sampling technique to select study participants from each hospital. We selected every three mothers in consecutive order of arrival at each hospital, until the sample size was reached.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of sampling procedure.

Data collection methods and procedures

We conducted face-to-face interviews using a pre-tested and structured questionnaire to collect participants’ data. The interviews were conducted after mothers had given birth and before discharge from the hospital. Measurement of mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) in the mother and the infant’s weight at birth within 30 minutes of delivery were taken. The questionnaire was adapted from various published studies15–17,20,23 and modified to meet the aims of the current study. The questionnaire was first translated from English into Afaan Oromo language and then back translated into English by two independent translators to ensure that the questions were clear and elicited relevant information. The questionnaire included sociodemographic information, obstetric history, maternal medical history, maternal behavioral factors, and birth outcome assessment. The data were collected by eight trained midwifery staff from each hospital, after receiving training on the objectives and ethical principles of the present research and organization of the questionnaires. The quality of the data was assured using properly designed and pretested questionnaires. Regular supervision and follow-up were conducted by the study supervisor. Additionally, regular checks for completeness and consistency of the data were done on a daily basis.

Data processing and analysis

The collected data were checked, coded, entered to Epi Info version 7.0, and exported to IBM SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for further analysis. Descriptive statistics such as frequency, mean, and cross tabulation were used to summarize the data. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to check the associations of individual variables with the outcome variables. Based on the results of bivariate logistic regression analysis, variables with a P value < 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted using a backward stepwise model. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistical test was used to check if the necessary assumptions for multiple logistic regression were fulfilled. P value >0.05 indicated that the model fit was good. Odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the degree of association between independent and dependent variables. Variables with a P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Madda Walabu University ethical review committee, and a letter of support was submitted to hospital managers (ref MWU RDD/231/18). An official letter was submitted to the medical director’s office in each hospital. Written informed consent was provided by each mother prior to the interview. Confidentiality was maintained by omitting any personally identifiable information from the questionnaires, and codes were assigned instead. The collected data were used for research purposes only.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of mothers in this study

From the total sample size of 580, 576 respondents were included in this study, with a response rate of 98%. Among the 576 mothers interviewed, 475 (82.5%) were aged 20 to 34 years followed by 67 (11.6%) aged less than 20 years. The mean age of mothers was 25 ± 5 years. Most respondents (489, 84.9%) were Oromo, followed by Amhara (71, 12.3%). A total of 360 (62.5%) mothers were Muslim and 200 (34.7%) were Orthodox Christian. Regarding educational status, 243 (42.2%) respondents had completed primary school and 129 (22.4%) completed secondary school. Most mothers (567, 98.4%) were married and more than half (313, 54.3%) were urban residents. A total of 378 (65.6%) respondents were homemakers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of 576 mothers who gave birth at Bale zone hospitals in Bale, Ethiopia, 2019.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 years | 89 | 15.4 |

| 20–34 years | 448 | 77.8 | |

| 35+ years | 39 | 6.8 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 489 | 84.9 |

| Amhara | 71 | 12.3 | |

| Other | 16 | 2.6 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 360 | 62.5 |

| Orthodox | 200 | 34.7 | |

| Protestant | 16 | 2.8 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 108 | 18.8 |

| Only reading and writing | 39 | 6.8 | |

| Primary school | 243 | 42.2 | |

| Secondary school | 129 | 22.4 | |

| College and above | 57 | 9.9 | |

| Marital status | Married | 567 | 98.4 |

| Single | 6 | 1.0 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Residence | Urban | 313 | 54.3 |

| Rural | 263 | 45.7 | |

| Occupation | Government employee | 50 | 8.7 |

| Homemaker | 378 | 65.6 | |

| Merchant | 78 | 13.5 | |

| Day laborer | 14 | 2.4 | |

| Farmer | 36 | 6.3 | |

| Other | 20 | 3.5 | |

| Income (ETB) | <1000 | 242 | 42.0 |

| 1001–2000 | 159 | 27.6 | |

| 2001–3675 | 146 | 26.3 | |

| >3675 | 29 | 5.0 |

Obstetric-related characteristics of respondents

Among 576 mothers enrolled in the study, 377 (65.5%) were multigravida and in 534 (92.7%), the pregnancy was wanted. Most mothers (265, 69.9%) had an interpregnancy interval of 24 to 59 months followed by ≤23 months (77, 20.3%). A total of 521 (90.5%) mothers attended ANC follow-up, 379 (65.8%) had their first follow-up during the first trimester of pregnancy, 250 (43.4%) had at least four ANC visits, and 320 (55.6%) mothers took folic acid supplementation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric-related characteristics of mothers who gave birth at Bale zone hospitals in Bale, Ethiopia, 2019.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | Primigravida | 199 | 34.5 |

| Multigravida | 377 | 65.5 | |

| Interpregnancy interval (N = 379) | ≤23 months | 77 | 20.3 |

| 24–59 months | 265 | 69.9 | |

| ≥60 months | 37 | 9.8 | |

| Pregnancy status | Wanted | 534 | 92.7 |

| Unwanted | 42 | 7.3 | |

| ANC follow-up | Yes | 521 | 90.5 |

| No | 55 | 9.5 | |

| Folic acid supplementation | Yes | 320 | 55.6 |

| No | 256 | 44.4 | |

| Contraceptive use | Yes | 215 | 37.3 |

| No | 361 | 62.7 | |

| Type of contraceptive used (N = 215) | Depo-Provera | 147 | 68.3 |

| Implanon | 44 | 20.4 | |

| Pills | 17 | 7.9 | |

| Others | 7 | 3.2 |

ANC, antenatal care.

Pregnancy- and labor-related characteristics of mothers

In the 576 participants, 138 (24%) mothers had pregnancy complications during the current pregnancy, among which 74 (12.8%) had PROM, and 42 (7.3%) had pregnancy-induced hypertension. Among all births, 90 (15.6%) mothers experienced labor complications, among which 32 (35.5%) had prolonged labor and 16 (17.7%) had obstructed labor. In approximately 485 (84.2%) mothers, labor was spontaneous, 464 (80.6%) had spontaneous vaginal delivery, and 77 (13.4%) had cesarean delivery. Among participants, 85 (15%) mothers had a previous poor obstetric history, 45 (52.9%) had abortion, and 23 (27%) experienced prenatal death (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pregnancy- and labor-related characteristics of mothers who gave birth at Bale zone hospitals in Bale, Ethiopia, 2019.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current pregnancy complications | Yes | 138 | 24.0 |

| No | 438 | 76.0 | |

| PROM | Yes | 74 | 12.8 |

| No | 502 | 87.2 | |

| PIH | Yes | 42 | 7.3 |

| No | 534 | 92.7 | |

| APH | Yes | 15 | 2.6 |

| No | 561 | 97.0 | |

| Labor complications | Yes | 90 | 84.4 |

| No | 486 | 15.6 | |

| Type of labor complications (N = 90) | Prolonged labor | 32 | 35.5 |

| Obstructed labor | 16 | 17.8 | |

| Malposition | 17 | 18.9 | |

| Malpresentation | 10 | 9.0 | |

| Other | 15 | 16.6 | |

| Status of labor | Spontaneous | 485 | 84.2 |

| Induced | 91 | 15.8 | |

| Mode of delivery | SVD | 464 | 80.6 |

| Cesarean delivery | 77 | 13.4 | |

| Instrumental | 33 | 5.7 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Previous poor obstetric history | Yes | 85 | 14.8 |

| No | 481 | 85.2 | |

| Type of poor obstetric history (N = 85) | Prenatal death | 23 | 27 |

| Abortion | 45 | 52.9 | |

| Congenital anomalies | 9 | 10.6 | |

| Other | 8 | 9.4 |

APH, Antepartum hemorrhage; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension; PROM, premature rupture of membranes; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Medical illness and exposure status of mothers

In this study, 68 (11.8%) participants had a history of medical illness, 25 (36.7%) had anemia, and 11 (16.1%) mothers each had HIV/AIDS and urinary tract infection. Most respondents (468, 81.3%) had MUAC ≥23 cm. In total, 215 (37.3%) mothers used modern contraceptives prior to their current pregnancy, among which 147 (68.3%) used Depo-Provera. Approximately 105 (18.2%) respondents had a history of drug exposure during their current pregnancy; 61 (58%) used antibiotics and 35 (33.3%) used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Most (425, 73.8%) mothers drank coffee during the current pregnancy and 44 (7.6%) had a history of alcohol intake (Table 4).

Table 4.

Medical illness and exposure status of mothers who gave birth at Bale zone hospitals in Bale, Ethiopia, 2019.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical illness | Yes | 68 | 11.8 |

| No | 508 | 88.2 | |

| Alcohol intake during current pregnancy | Yes | 44 | 7.6 |

| No | 532 | 92.4 | |

| Coffee use | Yes | 425 | 73.8 |

| No | 151 | 26.2 | |

| Drug exposure during current pregnancy | Yes | 105 | 18.2 |

| No | 471 | 81.8 | |

| Maternal hemoglobin | <11 g/dL | 104 | 18.1 |

| ≥11 g/dL | 472 | 82.9 | |

| MUAC | <23 cm | 108 | 18.7 |

| ≥23 cm | 468 | 81.3 | |

| Type of pregnancy | Singleton | 558 | 96.9 |

| Multiple | 18 | 3.1 |

MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference.

Prevalence of adverse birth outcomes

Our study findings showed that the prevalence of adverse birth outcomes among study participants was 21% (121/576). Among 576 births, 45 (7.8%) were stillbirth, 70 (12.2%) were LBW, 49 (8.5%) were preterm birth, and 18 (3.1%) involved congenital anomalies (Table 5).

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with adverse birth outcomes among mothers who gave birth at Bale zone hospitals in Bale, Ethiopia, 2019.

| Variables |

Adverse birth outcomes |

COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| ANC follow-up | Yes | 89 | 432 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 32 | 23 | 6.75 (3.77–12.09) | 6.58 (3.25–13.32) | <0.001 | |

| PROM | Yes | 35 | 62 | 2.58 (1.6–4.15) | 2.31 (1.26–4.21) | 0.006 |

| No | 86 | 393 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Type of pregnancy | Singleton | 112 | 446 | 1 | 1 | |

| Multiple | 9 | 9 | 3.98 (1.54–10.26) | 4.74 (1.55–14.45) | 0.006 | |

| Maternal hemoglobin | <11 g/dL | 54 | 50 | 6.52 (4.1–10.35) | 3.22 (1.85–5.58) | <0.001 |

| ≥11 g/dL | 67 | 405 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MUAC | <23 cm | 52 | 56 | 5.37 (3.4–8.47) | 5.93 (3.49–10.08) | <0.001 |

| ≥23 cm | 69 | 399 | 1 | 1 | ||

P < 0.05.

ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PROM, premature rupture of membranes; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference.

Factors associated with adverse birth outcomes

In bivariate analysis, mother’s age, educational status, residence, occupation, interpregnancy interval, inadequate ANC follow-up, multiple pregnancy, hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL, and MUAC ≤ 23 cm were significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes. In the multivariate analysis, mothers who had no ANC follow-up during the current pregnancy were six times more likely to have adverse birth outcomes than mothers who attended ANC visits (AOR = 6.58, 95% CI 3.25–31.32; P < 0.001). Mothers who had multiple pregnancies were approximately five times more likely to have adverse birth outcomes than those with a singleton pregnancy (AOR = 4.74, 95% CI 1.55–14.45; P = 0.006). Similarly, mothers who had PROM during the current pregnancy were approximately two times more likely to have adverse birth outcome than mothers who had no PROM (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.21; P = 0.006). Mothers with hemoglobin < 11 g/dL were three times more likely to have adverse birth outcomes than those with hemoglobin ≥11 g/dL (P < 0.001). Furthermore, mothers with MUAC < 23 cm were approximately six times more likely to have adverse birth outcomes as compared with mothers who had MUAC >23 cm (AOR = 5.93, 95% CI 3.49–10.08; P < 0.001).

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that the prevalence of adverse birth outcomes was 21% (121/576). From 576 births, 45 (7.8%) were stillbirth, 70 (12.2%) were LBW, 49 (8.5%) were preterm birth, and 18 (3.1%) had congenital anomalies. This finding was nearly in line with a study in Shire Suhul Hospital in the Tigray Region in which 22.5% of mothers had adverse birth outcomes.17 However, the current prevalence is higher than the finding in Hawassa city governmental health institutions, where 18.3% of mothers experienced adverse birth outcomes.18 The variation in these findings could be attributable to variation in the quality of maternal health care, facilities, and study areas.

The prevalence of adverse outcomes in the present study was lower than those in Dessie Referral Hospital, Negest Elene Mohammed Memorial General Hospital in Hosanna Town, and Gondar University Hospital,15,16,20 with 32%, 24.5%, and 23.5%, respectively. The differences may be attributable to our study involving one referral and three general hospitals. Most normal deliveries are handled in health centers and general hospitals and more complicated cases are transferred to referral hospitals, such that the prevalence of adverse outcomes may be increased in referral hospitals. However, differences in study area, quality of maternal health care, and the interventions undertaken among studies could also account for the variations.

In this study, mothers who had no ANC follow-up during the current pregnancy were six times more likely to have adverse birth outcomes than mothers who attended ANC visits. This finding is inconsistent with studies conducted in Dessie Referral Hospital, Negest Elene Mohammed Memorial General Hospital in Hosanna Town, and Gondar University Hospital.15,16,20 This might be because an absence of ANC follow-up or a lack of some health services can result in failed early identification and management of pregnancy-related problems, which may influence mothers’ choice of hospital in which to deliver.

This study revealed that mothers who had PROM during the current pregnancy were two times more likely to have adverse birth outcomes. This is in line with a previous study in Shire Suhul Hospital in Tigray and Gondar University Hospital.17,20 This could be related to PROM during pregnancy being a risk factor for preterm labor and its complications, chorioamnionitis abruptio placentae, and oligohydramnios, which leads to oxygen deprivation in utero.

In this study, multiple pregnancy was significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes, with mothers who had multiple pregnancy nearly five times more likely have adverse outcomes than those with a singleton pregnancy. This is consistent with a previous finding in Shire Suhul Hospital and Jimma University Specialized Hospital.17,23 Multiple pregnancy increases the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality and is associated with nearly all known complications of pregnancy including antepartum hemorrhage, congenital malformation, intrauterine growth restriction, malpresentation and anemia, which further increase the risk of adverse birth outcome.

Mothers who had MUAC < 23 cm were approximately six times more likely to experience adverse birth outcomes than those whose MUAC was ≥23 cm. This is supported by a research finding in Dessie Referral Hospital.15 This result may be because maternal malnutrition leads to intrauterine growth retardation, which further leads to adverse birth outcomes. However, mothers with hemoglobin < 11 g/dL were three times more likely to experience adverse birth outcomes. This is in line with research findings in Dessie Referral Hospital, Negest Elene Mohammed Memorial Hospital, Southern Nation Nationalities Region, Ethiopia; and Adwa General Hospital in northern Ethiopia.15,16,21 The reason for this finding may be because anemia affects the oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin and its transport to the placenta, which nourishes the fetus in utero.

Conclusion

The findings of this study revealed that in the Bale zone, approximately one in five mothers had adverse birth outcomes. Inadequate ANC, multiple pregnancies, PROM during the current pregnancy, hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL and MUAC < 23 cm were significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes.

Recommendation

The Ministry of Health should design a strategy that focuses on prevention of pregnancy complications through providing training for midwives in early detection of complications during pregnancy.

The Bale zone health office should provide supportive supervision for health professionals working in maternal and child health outpatient departments to increase their capacity in screening mothers’ nutritional status and providing health education for pregnant women.

Goba Referral Hospital, Robe District Hospital, Ginnir District Hospital, and Delomenna District Hospital should raise awareness regarding appropriate supplementation with ferrous sulfate and folic acid, based on standard guidelines.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605211013209 for Adverse birth outcomes and associated factors among mothers who delivered in Bale zone hospitals, Oromia Region, Southeast Ethiopia by Sisay Degno, Bikila Lencha, Ramato Aman, Daniel Atlaw, Ashenafi Mekonnen, Demelash Woldeyohannes, Yohannes Tekalegn, Sintayehu Hailu, Bedasa Woldemichael and Ashebir Nigussie in Journal of International Medical Research

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Madda Walabu University for funding this research project. Our deepest gratitude also goes to the study participants for their valuable time and cooperation in providing the necessary information. Finally, we would like to thank the data collectors for their devotion and quality work during data collection.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Madda Walabu University. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Authors' contributions: All authors were involved in designing the study, analyzing the data, and drafting the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Sisay Degno https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4808-1415

Bikila Lencha https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0840-9460

Daniel Atlaw https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2968-4958

Ashenafi Mekonnen https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5272-5829

Yohannes Tekalegn https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6628-8180

Bedasa Woldemichael https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1085-7847

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, et al. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 10: S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Dinter MC, Graves L.Managing Adverse Birth Outcomes: Helping Parents and Families Cope. Am Fam Physician 2012; 85: 900–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88: 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrant BM, Stanley FJ, Hardelid P, et al. Stillbirth and neonatal death rates across time: the influence of pregnancy terminations and birth defects in a Western Australian population-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016; 16: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2015; 4: e98–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Watananirun K, et al. Global, regional and national levels and trends of preterm birth rates for 1990 to 2014: protocol for development of World Health Organization estimates. Reprod Health 2016; 13: 76. Available from: 10.1186/s12978-016-0193-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EDHS. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Preterm birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Richard E. Behrman and Adrienne Stith Butler, editor. Washington DC; 2007. pp. 124–136.

- 9.World Health Organization. Born Too Soon, global action report on preterm birth. 2012.

- 10.UNICEF. Nutrition: low birth weight. WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low Birth Weight Policy Brief. 2014.

- 11.World Health Organization. Ending preventable stillbirths. 2016.

- 12.Gedefaw G, Alemnew B, Demis A.Adverse fetal outcomes and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 2020; 20: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.USAID. Ethiopian profile of preterm and low birth weight prevention and care. 2015.

- 14.Bililign N, Legesse M, Akibu M.A Review of Low Birth Weight in Ethiopia: Socio-Demographic and Obstetric Risk Factors Abstract Magnitude of low birth weight. iMedPub Journals 2018; 5: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherie N, Mebratu A.Adverse Birth Out Comes and Associated Factors among Delivered Mothers in Dessie Referral Hospital, North East Ethiopia Abstract. iMedPub Journals 2017; 1: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdo RA, Endalemaw TB, FY T.Prevalence and associated Factors of Adverse Birth Outcomes among Women Attended Maternity Ward at Negest Elene Mohammed Memorial Journal of Women’s Health Care. J Women’s Heal Care 2016; 5: 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adhena T, Haftu A, Gebreegziabher B.Assessment of Magnitude and Associated Factors of Adverse Birth Outcomes among Deliveries at Suhul Hospital Shire, Tigray, Ethiopia From September, 2015 to February, 2016. Biomed J Sci Tech Res 2017; 1: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsegaye B, Kassa A.Prevalence of adverse birth outcome and associated factors among women who delivered in Hawassa town governmental health institutions, south Ethiopia, in 2017. Reprod Health 2018; 15: 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebremeskel F.Determinants of Adverse Birth Outcome among Mothers who Gave Birth at Hospitals in Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia-: A Facility Based Case Control Study. Qual Prim Care 2017; 25: 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adane AA, Ayele TA, Ararsa LG, et al. Adverse birth outcomes among deliveries at Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014; 14: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebregzabiher Y, Haftu A, Weldemariam S, et al. The Prevalence and Risk Factors for Low Birth Weight among Term Newborns in Adwa General Hospital, Northern Ethiopia. Obstet Gynecol Int 2017; 2017: 2149156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sara J, Haji Y, Gebretsadik A.Determinants of maternal death in a pastoralist area of Borena Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia: Unmatched case-control study. Obstet Gynecol Int 2019; 2019: 5698436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeshialem E, Alemnew N, Abera M, et al. Determinants of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes among Mothers Who Gave Birth from Jan 1–Dec 31/2015 in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Case Control Study, 2016. Med Clin Rev 2017; 3: 22. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605211013209 for Adverse birth outcomes and associated factors among mothers who delivered in Bale zone hospitals, Oromia Region, Southeast Ethiopia by Sisay Degno, Bikila Lencha, Ramato Aman, Daniel Atlaw, Ashenafi Mekonnen, Demelash Woldeyohannes, Yohannes Tekalegn, Sintayehu Hailu, Bedasa Woldemichael and Ashebir Nigussie in Journal of International Medical Research