Abstract

Objectives:

African American women are disproportionately impacted by intimate partner violence (IPV)-related homicide. They reflect the second highest prevalence rates and experience the highest rates of murder resulting from IPV victimization. Although most survivors note that they have experienced rejection and anticipatory stigma as barriers to their help seeking, African American women additionally experience racism and racial discrimination as obstacles that may further preclude their help seeking. This systematic review highlights African American women’s experiences of rejection from providers and the effects that it may have upon their ability to secure urgent aid.

Method:

A dearth of literature examines the subtle ways that African American women survivors experience rejection resulting from the interlocking nature of race, class, and gender oppression. Fundamental to developing more culturally salient interventions is more fully understanding their help-seeking experiences. A systematic review was conducted to provide a critical examination of the literature to understand the intersections of IPV and help-seeking behavior among African American women. A total of 85 empirical studies were identified and 21 were included in the systematic review. The review illuminates both the formal and semiformal help-seeking pathways.

Results:

We recommend integrating anti-Blackness racist praxis, incorporating African American women’s ways of knowing and centralizing their needs in an effort to improve the health and well-being of this population.

Conclusions:

Eliminating barriers to more immediately accessing the domestic violence service provision system is key to enhance social work practice, policy, and research with African American female survivors of IPV.

Keywords: domestic violence, intimate partner violence, African American women, intersectionality, help seeking

Intimate partner violence (IPV) within heterosexual relationships is a critical social and public health problem that disproportionately affects African American women (Petrosky et al., 2017; Violence Policy Center, 2020). IPV includes any physical or sexual violence, psychological aggression, stalking, and/or controlling behaviors (Breiding et al., 2015). African American women are more likely than women of other racial and ethnic groups in the United States to be murdered by their intimate partner (Violence Policy Center, 2020). Furthermore, African American women experience IPV-related homicide at younger ages. The average age that she is murdered by her intimate partner is 36 years old, which is 5 years younger than the national average (Violence Policy Center, 2020). Still, they are more likely to remain with their abusive partner rather than seek help from service providers due, in part, to the racism and racial discrimination they experience during help seeking (Bent-Goodley, 2013; Petrosky et al., 2017). Fundamental to improving their outcomes is more fully understanding the effects that representational intersectionality has upon their IPV help-seeking experiences. Hence, this systematic review of the literature examines the impact of African American women IPV survivors’ experiences with help seeking through the lens of controlling images.

Review of the Literature

Help Seeking

Help seeking is defined as the process that a survivor utilizes to disclose, garner support, and/or secure formal services for partner abuse (Goodson & Hayes, 2018; Stork, 2008). Help seeking within the African American community is complex and often compounded by social and racial pressures. African American women are often celebrated for their strength, resilience, and ability to privately handle their own problems (Bent-Goodley, 2013; Walker-Barnes, 2014). This stance counters traditional IPV help-seeking values of securing more public mechanisms of assistance (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006; Fugate et al., 2005; Gillum, 2008). In addition, African American women are often socially perceived as betraying their partner and the entire African American community when they violate their socially prescribed role of protecting their man from the police rather than secretly suffer from victimization (Bent-Goodley, 2013; Nash, 2005; Waller, 2016). This is particularly at issue since the criminal justice system historically gives African American male perpetrators harsher penalties than White males (Alexander, 2012; Waller, 2016). During criminal justice system intervention, survivors are typically referred to the shelter for emergency housing and the health care system for immediate medical attention (Few, 2005). Due to cultural norms of religiosity within the Black community, it is common for survivors to also garner assistance via their church and religious resources (Cox & Diamant, 2018; Potter, 2007).

Intersectionality

Intersectionality illuminates the “triple jeopardy” sociological barriers of racism, capitalism, and sexism that African American women experience (Aguilar, 2012). The idea that multiple oppressions reinforce each other to create new categories of suffering was created by the Combahee River Collective, a radical Black feminist organization formed in 1974 and named after Harriet Tubman’s 1863 raid on the Combahee River in South Carolina that freed 750 enslaved people (K. Y. Taylor, 2019). Later, the term and the analysis that articulates and animates the meaning of intersectionality was conceptualized by second- and third-wave feminists (Crenshaw, 1991; K. Y. Taylor, 2019). According to Crenshaw (1991), intersectionality elucidates the identity politics of two marginalized groups—women and people of color—and is informed by critical race theory, feminist legal theory, and Black feminist thought (Aguilar, 2012). Intersectionality utilizes three constructs that may preclude African American women from securing necessary assistance: (1) structural intersectionality, (2) political intersectionality, and (3) representational intersectionality. Structural intersectionality provides a framework for exploring African American women’s social mapping and juxtaposes their qualitative differences with that of White women’s experiences. The systemic barriers that African American women experience during formal help seeking evidence this phenomenon. Political intersectionality frames how the agendas of feminist and antiracist politics concurrently marginalize the needs of African American women. This is reflected in the paucity of resources and dearth of culturally congruent interventions that have been specifically designed and implemented, as well as the differential way they are treated when engaging with various aspects of the service provision system (Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013; Petrosky et al., 2017). Representational intersectionality identifies the nature in which pop culture’s representations objectify, denigrate, and disempower African American women as evidenced in the racialized archetypes and tropes used to minimize African American women’s experiences and diminish their voices. Racialized images that essentialize and objectify African American women likely underpin the implicit biases that frame their adverse interactions with domestic violence service providers during help seeking (Carr et al., 2014; J. D. Johnson et al., 2009).

Controlling Images

Collins’s (2002) conceptualization of controlling images highlights the ways in which biological determinism and oppression serve to justify the subordination of African American women. Referring to controlling images like the Mammy, Jezebel, and Sapphire as stereotypes or merely widely held beliefs fail to capture the ways in which these images are used to normalize exploitation and violence against African American women through the practice of essentialization. Beyond labeling and overgeneralizing, controlling images reify the essentialization of characteristics historically attributed to African American women in this way rationalizing practices and policies that serve to further oppress them. Essentialism ignores the socio-political factors that contribute to individual- and group-level behavioral patterns and experiences. Essentialism reflects an idea or belief that group members have inherent, natural, or essential qualities based solely on their group membership. To essentialize means to disregard the role that oppression has in shaping the lived experiences of group members, thereby, contributing to the development of damaging stereotypes and controlling images (Azzopardi & McNeill, 2016; Soylu Yalcinkaya et al., 2017). To understand the controlling images surrounding African American women, one must use an intersectional framework that speaks to a critical analysis of the oppression and exploitation that they experience, along with their perpetual othering.

Throughout history, there have been three ubiquitous stereotypical images associated with African American women: the Jezebel, the Mammy, and the Sapphire/Matriarch. These stereotypes have served to justify their sexual and economic exploitation. They are grossly oversimplified fabrications that perpetuate and rationalize ongoing disparities and a failure to develop appropriate policy responses to their abuse and mistreatment (Collins, 1999). The following section will review the three prevailing stereotypes mentioned as well as a well-known cultural script, “The Strong Black Woman” (SBW) which may be viewed as a historical trauma response.

The Jezebel stereotype served to justify the sexual exploitation of African American women. African American women as “Jezebels” were considered hypersexual, immoral, and aggressive. Their sexual anatomy was juxtaposed against that of White women and contributed to pseudoscience that suggested sexual deviance (Degruy Leary, 2005; Harris-Lacewell, 2001). Raping African American women contributed to the expansion of the slave population and therefore the American economy. Framing African American women as inherently hypersexual rationalized their sexual abuse and torture. As a result, their sexual production and reproduction were exploited with little to no repercussions. Postslavery, the rape and sexual abuse of African American women continued, sometimes at the hands of police officers and in the presence of their families (McGuire, 2004). We continue to see evidence of African American women’s sexual exploitation. Cases like that of Daniel Holtzclaw, a police officer whose pattern of targeting African American women went ignored for months despite reports suggest the continued normalization of their abuse. Holtzclaw admitted targeting African American women based on the confidence that their complaints would not be believed (Holcombe & McLaughlin, 2019). These stereotypes also contribute to disparate outcomes in treatment. For example, African American women are more likely to experience secondary revictimization when seeking support for sexual assault and frequently question their own experiences of sexual assault and rape (Tillman et al., 2010; Wyatt, 1997).

The fact that African American women also served a role in maintaining the homes and families of White people during and after slavery necessitated another stereotype. The Mammy trope characterized African American women as strong, large, asexual, and obedient and was in direct contradiction to their framing as Jezebels. The Mammy is one of the most predominant stereotypes associated with African American women. She is often represented in social media depictions as an older, religious, and trustworthy woman devoid of personal needs (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009; West, 1995).

The Mammy was thought to keep other African Americans in line and implied obedience and compliance with the institution of slavery. This stereotype served to justify the exploitation of African American women as caretakers with boundless resources for serving others. After slavery, African American women continued to be exploited, working for less pay, with harsher treatment and in jobs that often had no specific designation of responsibilities (Abramovitz, 1996; Katznelson, 2005). Each time an African American woman left her home to provide for her family, her safety was at risk. The simple acts of traveling to and from work, combined with working and living in the homes of others, removed African American women from the protection of family and community (Abramovitz, 1996; Collins, 2002). We continue to see the economic exploitation of African American women based on their perceived strength and selflessness. They are often believed to be better equipped to handle more difficult tasks in the workforce and are largely underdiagnosed for depression and stress-related disorders (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2008; Offutt, 2013; Romero, 2000; Woods-Giscombé, 2010).

The Sapphire/Matriarch/Angry Black Woman stereotype has historically been used as a justification for African American poverty and harsh treatment in social welfare systems. She is characterized as angry, confrontational, and lazy. While the Mammy was acceptably cheeky, the Sapphire was framed as insolent and disrespectful. She was hot-tempered, hypersensitive, and especially emasculating toward African American men. This stereotype served to punish African American women who challenged the status quo, encouraging them to remain docile and submissive like the fabricated Mammy (Pilgrim, 2012). The criticism of the African American matriarch by those like Daniel Patrick Moynihan relied on a neoliberal framing that ignored the ongoing assimilation challenges faced by African American families (Collins, 2002; Walker-Barnes, 2014). African American women were forced to work alongside African American men during and postslavery. Convict leasing, Black codes, and Jim Crow–era policies demanded that African American women work outside of the home, thus preventing them from adhering to the cult of domesticity. While the American family ethic and the cult of domesticity decreed that a woman’s place was in the home, the ongoing marginalization and exploitation of African American men made this nearly impossible for African American families (Abramovitz, 1996). American values of rugged individualism and the myth of meritocracy further demoralized African American women and punished them for surviving and etching out a place in American society. Ronald Regan’s “Welfare Queen” is a modern-day representation of this stereotype that contributes to the false depiction of African American women as the undeserving face of social welfare and a cancer to African American families and communities.

The SBW archetype is a remnant of long-held stereotypes, essentialization and trauma responses. It is a cultural script that serves as an exemplar, particularly for middle-class African American women. At its heart, it reinforces African American women’s supposed inherent ability to withstand hardships while appearing composed and unperturbed. Major aspects of this ethos include “embodiment of strength,” “supramorality,” “self-reliance,” “masking emotions,” and “obligation to community and others” (Abrams et al., 2014; Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009; Gillespie, 1984; Nelson et al., 2016; Romero, 2000). Adherence to the archetype is associated with many outcomes, which reflect both in- and out-group responses to the essentialization of African American women’s strength. From medical students who believe African Americans have a higher tolerance for pain (Hoffman et al., 2016) and disparities in maternal mortality (Flanders-Stepans, 2000) to retraumatization and oppressive experiences in mental health treatment (Kolivoski et al., 2014; Tillman et al., 2010), African American women continue to be subjected to how others interpret these widely held misconstructions. Quantitative and qualitative research have found positive relationships between adherence to the SBW archetype and stress-related disorders, maladaptive coping patterns, and depression and poor self-esteem (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2007; Donovan & West, 2014; Green, 2011; Hamin, 2008; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). African American women report beliefs that their strength is tied to their Blackness and feel they must mask their vulnerability while prioritizing others’ needs. Many indicate being socialized early on as girls to demonstrate fortitude in the face of social inequality, racism, sexism, and abuse (Abrams et al., 2014; Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2008; Walker-Barnes, 2014). Using an intersectional framework for understanding the impact of the essentialization of African American women’s strength and sexuality supports a critical examination of their experiences with intimate partner abuse and the systems that are in place to respond.

Current Study

The literature currently lacks a systematic analysis that examines African American women’s help-seeking experiences across the various pathways of domestic violence service provision. Survivors typically secure assistance from formal providers within the criminal justice, shelter, and health care systems (Bent-Goodley, 2004, 2005; Gillum, 2008). African American survivors additionally heavily rely upon the Black church for guidance and support (Lacey et al., 2020). This review is timely, particularly since it provides a comprehensive analysis of the existing gaps within the domestic violence service provision system at a time when the rates of perpetration have significantly increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Buttell & Ferreira, 2020) and the sustained emphasis upon anti-Blackness racism and its implications upon African American women’s ability to secure timely intervention (Laurencin & Walker, 2020; Petrosky et al., 2017). Information from this review could be utilized as an initial step to providing culturally nuanced services and supports that more fully support the needs of African American women IPV survivors.

Method

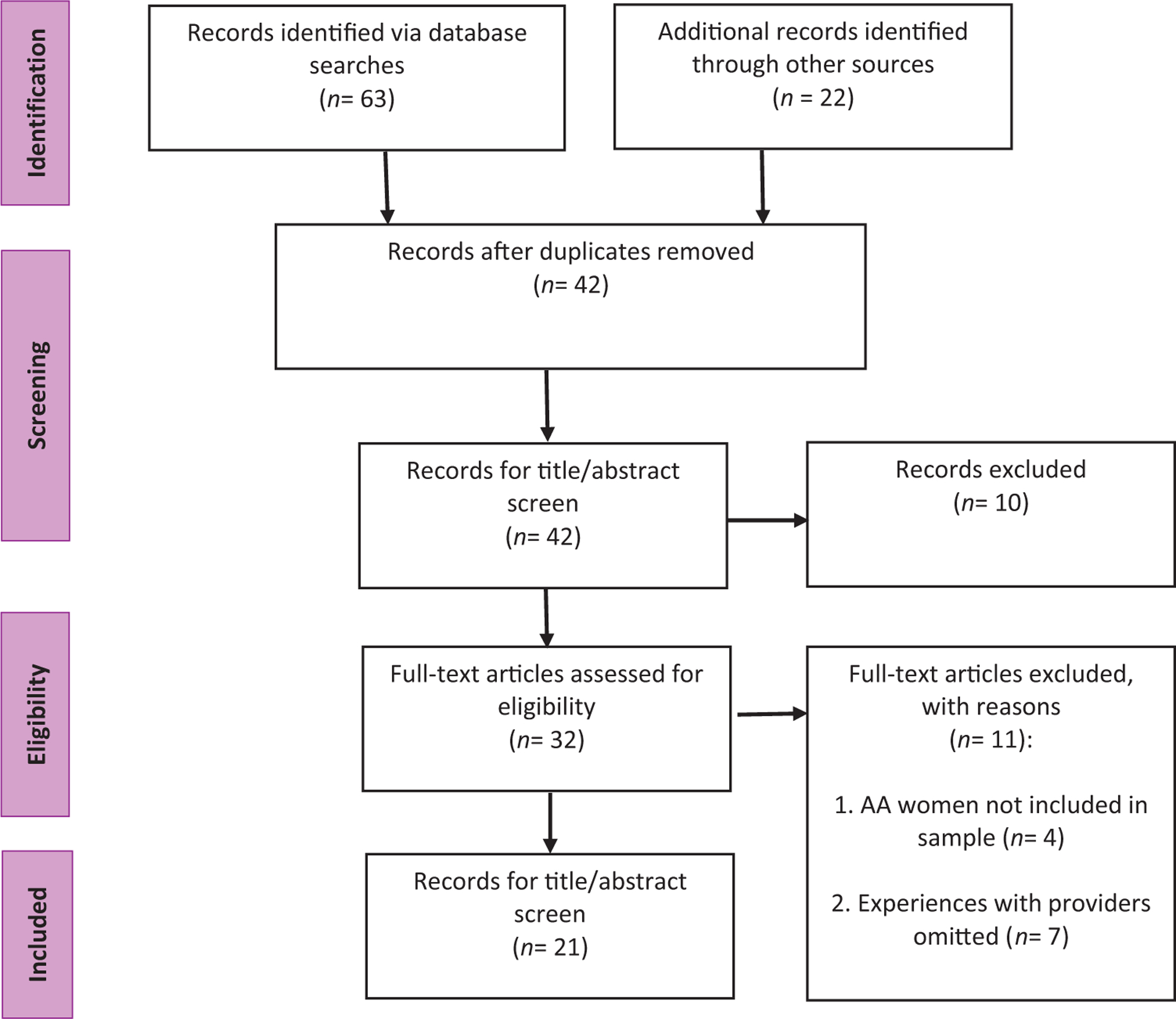

A systematic review of the literature was utilized to investigate the ways that controlling images impact African American women IPV survivors’ help seeking. Our research team utilized the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocol for systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2015). Figure 1 depicts the steps in our review process. We employed three strategies to search the literature: (1) database search for peer-review publications, (2) internet searches for articles not captured in databases, and (3) the Cochrane collaboration for gray literature. We conducted a systematic search in the following six databases: (1) Academic Search Complete, (2) CINAHL complete, (3) Criminal Justice Abstracts, (4) MED-Line, (5) Social Sciences Abstracts, and (6) Social Work Abstracts. The following search strings were utilized: (1) intimate partner violence or domestic violence or partner abuse, (2) help seeking, and (3) African American women or Black women. A total of 63 empirical studies were identified in this search.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis flow diagram.

To ensure we were capturing the experiences of African American women’s help seeking, we included scholarly publications based on the team’s predetermined requirements. We included either quantitative or qualitative articles that captured African American women’s help-seeking experiences with formal providers within the criminal justice, shelter, and health care systems, as well as quasi-trained clergy within the Black church. Criteria included limits that were set for the publication year (2004–2018), document type (peer-reviewed, journal-article), language (English), and the author’s institutional affiliation (United States). Help seeking was conceptualized in the IPV literature in 2005 (Liang et al., 2005). To ensure we accounted for articles that described this phenomenon, our search began with articles published in 2004. Only articles that included African American women, aged 18+ years old, within heterosexual relationships as part of the sample were included in the review.

To ensure we accounted for IPV articles that were not published in scholarly journals, we conducted a Google search and found an additional 12 articles for review. There are also a few scholars whose work centralizes African American women’s needs, namely, Tameka Gillum, Tricia B. Bent-Goodley and Nkiru Nnawulezi. We conducted a search for any articles published by these researchers between 2004 and 2018 that included African American women’s help-seeking experiences. This method accounted for an additional 10 articles for review. We also searched the gray literature via the Cochrane collaboration, however, were unable to find any additional articles. Overall, this mechanism provided an additional 22 articles for review.

In total, there were 85 articles. We removed 43 duplicates. Based on the aforementioned criteria, 42 abstracts were reviewed and 21 met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review. The team reviewed each of the publications, based on the aforementioned inclusion criteria. Articles were excluded for the following reasons: (1) African American women were not specifically identified as part of the sample and (2) women’s experiences with providers were omitted. Publications that included samples of Black women rather than specifically identifying African American women were excluded. Black women are sometimes viewed as a monolith; however, there are within-group differences in their sociohistorical context as this population includes African, African American, Afro Caribbean, Black Latinas, and Black European women (Brondolo et al., 2009; V. M. S. Johnson, 2008; Lacey et al., 2016). Furthermore, African American women are the largest population of Black women in the United States (V. M. S. Johnson, 2008). Although there is emerging literature that examines the help-seeking experiences of African American women who self-identify as women within same-sex relationships (Guadalupe-Diaz & Jasinski, 2017), this review focuses upon those within heterosexual relationships.

Results

The 21 articles included in this systematic review are noted in Table 1. Quantitative and qualitative studies utilized nationally representative, as well as clinic- and community-based samples of low and middle-class African American women, aged 18–68 years old, residing in rural, suburban, and urban areas in the United States. Samples of religious women mostly self-identified as Christian or Muslim, and some noted they were religiously unaffiliated but spiritual in their beliefs and practices. Quantitative data were collected either via face-to-face, computer-assisted, or telephone landlines. Studies that employed qualitative methods utilized purposive and convenience sampling methods. These data were collected either via individual, face-to-face, or focus group interviews. Studies that employed focus groups may not fully represent the voices of all of the study participants (McLafferty, 2004). In general, studies that employ focus groups as a mechanism for data collection are fraught with methodological issues related to confidentiality, particularly since IPV survivors likely experience shame and stigma resulting from their abuse and may not readily share within a focus group setting (McLafferty, 2004; Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). Notwithstanding, full sample characteristics are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics and Relevant Findings.

| Citation | Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anyikwa (2015) | Quantitative | 110 Black w, ages 18–66; 93% AA | FORMAL: (1) mostly police, less shelter, and EDs; (2) 1/3 did not engage police due to fear of how men would be treated |

| Bent-Goodley & Fowler (2006) | Qualitative | 19 AA faith-based leaders and congregants; 13 women and six men | (1) Religion/biblical principles used to keep women in abusive relationships, (2) sexism/sex-role perceptions a barrier, and (3) clergy needs to understand how abuse impacts women’s spirituality |

| Cheng &Lo (2015) | Quantitative | 6,589 w who completed the NVAWS; nationally rep. sample, include AA women | (1) Least likely to seek help from MH professionals; (2) severe controlling behaviors, severe forced sex, or frequent physical assault increased MH help seeking; (3) access to free svcs increased likelihood of utilization |

| Davies et al. (2007) | Quantitative | 500 w (69% AA; 21% Latina) | (1) Severity of violence the strongest predictor of police contact; (2) weapon use, threat, or attempted murder was the most serious incident, 69% of w had police contact; and (3) higher the women’s informal acceptance and support > likelihood of police contact |

| Deutsch et al. (2017) | Qualitative | 31 Participants (83% White; 17% AA, Latina) | AA women felt providers would neither believe them nor care about their legal outcomes; anticipated abuse from providers rather than safety; the least likely to follow through with legal proceedings |

| Dichter & Rhodes (2011) | Quantitative | 173 IPV victims; 79% AA women | (1) 97.6% used medical care, (2) 62.6% used general MH and said this helped them feel safer, and (3) 71.4% said that they were interested in MH |

| El-Khoury et al. (2004) | Quantitative | 376 women; 86% AA women | (1)Black w use prayer & White w MHC, (2) Black w found prayer > helpful than White, and (3) no ethnic differences in the utilization of clergy or medical professionals (clergy may be considered a “public” resource) |

| Few (2005) | Qualitative | 30 abused w; 10 AA/Black | (1) Only five women knew shelter existed, (2) most White women said the police recommended the shelter, (3) ashamed to engage police for help, (4) police told men to walk away or were later released, and (5) religious w had more difficulty leaving |

| Frasier (2006) | Quantitative | 193 women (75% AA) | Survivors believe in rape myth acceptance; the more likely a survivor ascribes to rape myth acceptance, the least likely to disclose victimization |

| Fugate et al. (2005) | Qualitative | 491 Abused women, 69% African, AA, Black | (1) 82% of the abused women did not contact an agency or counselor, (2) 74% of the women did not seek medical care, (3) 62% did not call the police, and (4) 29% did not talk to someone else, such as family and friends |

| Gillum (2009) | Qualitative | 14 AA w IPV survivors | Mainstream: (1) unwelcoming, unsupportive, (2) insensitive, and (3) barriers to adequate assistance; Culturally specific: (1) welcoming, (2) sensitive to leaving process, (3) more fully assist, and (4) supportive environment |

| Gillum (2008) | Qualitative | 13 AA w IPV survivors | (1) w dissatisfied w DV shelter programs, (2) lack of assistance, (3) harsher treatment, (4) racism exists within the legal system, and (5) lack of resources |

| Hamberger et al. (2007) | Quantitative | 132 w IPV victims obtaining services from a battered women’s program (39% AA; 51% White) | (1) AA w are more likely to access an emergency or urgent care; (2) all want physicians to provide gentle, competent physical exams and not victim-blame; (3) AA w want culturally competent treatment |

| Lucea et al. (2013) | Quantitative | 545 w of African descent (AA and Afro Caribbean) | (1) Only 57% seeking any help; (2) Of that, 13% sought medical; B-18% DV, C-37% community, and D-41% criminal justice resources. (2) Those who were employed were less likely to utilize health care resources; (3) w who did not access resources were unaware of them. |

| Nash & Hesterberg (2009) | Qualitative | Three abused religious women | (1) Biblical characters who suffered were drawn upon for encouragement, (2) religious coping doesn’t mean not doing anything, and (3) concerns abt race-class-gender oppression |

| Nicolaidis et al. (2010) | Qualitative | 31 AA women; four focus groups | (1) Intergenerational messages to avoid health care, (2) mistrust of the health care system as a “White” system, (3) negative experiences with health care attributed to racism, (4) expectation to be a “Strong Black Woman” acts as a barrier, (5) negative attitudes toward antidepressants, and (6) preferences for self-care |

| Nnawulezi & Sullivan (2013) | Qualitative | 14 Black/AA women | (1) Lack of culturally specific hair products, foods, and a homogeneous staff composition; (2) experienced microinsults, microassaults, and microinvalidations; and (3) there’s a belief that we are undeserving clients |

| Paranjape et al. (2007) | Qualitative | 30 AA women over 50 years old | (1) Spiritual sources were cited over physicians as being available to help FV survivors and (2) barriers to receiving assistance included negative encounters with physicians, lack of trust in the system, and dearth of age-appropriate resources |

| Potter (2007) | Qualitative | 40 Battered Black/AA women | (1) Vast majority of the w relied on their spirituality to help them get through and get out of the abusive relationships |

| Sabri et al. (2013) | Quantitative | 354 Black women (276 AA; 78 Afro Caribbean) | (1) 66% did not use MH resources; (2) more severe IPV, more severe MH problems (AA w with severe phys and psych abuse experiences, and high risk for lethality were significantly likely to have co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder and depression problems) |

| J. Y. Taylor (2005) | Qualitative | 21 AA w who experienced DV | (1) Negotiating shelter and navigating nebulous environments; (2) encountering racism, work, and the brick ceiling; and (3) cultivating and maintaining a strong back against racism |

Note. AA = African American. IPV = intimate partner violence. MH = mental health. DV = domestic violence. ED = emergency department.

Experiences With the Criminal Justice System

Seven articles examined African American women’s experiences with the criminal justice system. These studies revealed that survivors defer engaging with the criminal justice system and when they do, they often secure significantly delayed and/or inadequate assistance from providers (Anyikwa, 2015; Davies et al., 2007; Deutsch et al., 2017; Few, 2005; Frasier, 2006; Fugate et al., 2005; Lucea et al., 2013). A confluence of the aggressive, shrill, and emasculating Sapphire and the self-sufficient SBW may inhibit survivors from receiving the help that they need from law enforcement. These tropes may have led some police officers to discredit African American women’s urgent need for crisis intervention (Few, 2005) and may further have implications as to why they forgo police intervention: They believe that they will not be fully supported (Deutsch et al., 2017; Lucea et al., 2013). Few (2005) conducted a qualitative study of 30 women in a southern rural part of the United States. One of the African American participants shared that White police officers waited outside her home for nearly 30 min while her husband physically abused her (Few, 2005). Rather than providing more immediate assistance, they waited for her to crawl her battered body outside of her home before they intervened (Few, 2005). This incident may support the faulty premise that African American women are strong and subsequently have a diminished need for the same level of support and intervention that White women survivors are generally afforded (Few, 2005). Within the court system, perpetrators of sexual violence are less likely convicted when the survivor is an African American woman due to misperceptions that they secretly desire to get raped (Frasier, 2006; Tillman et al., 2010).

African American women’s internalization of society’s misrepresentations of their mannerisms, as depicted in the Sapphire and the SBW, is reflected and reinforced throughout their interactions with law enforcement. African American women generally forgo police intervention because they believe they can handle the situation better than officers (Anyikwa, 2015; Fugate et al., 2005; Lucea et al., 2013; Taft et al., 2009). Fugate and colleagues (2005) found that more than half (62%) of women avoided police intervention because they feared officers would mishandle the situation. Furthermore, internalization of the SBW may also account for the higher rates of bidirectional IPV found among African American couples (Palmetto et al., 2013), specifically since they tend to believe that they can exact their own form of justice upon the perpetrator. Studies interrogating the legal system reflect similar experiences of survivors’ diminished engagement and poor follow-through (Deutsch et al., 2017). Deutsch and colleagues (2017) conducted a series of focus groups and found that African American women tend to be uncooperative with the legal process because they feel like they will neither be believed nor fully supported. Survivors further expected that their cases would not be adequately adjudicated and they feared they would be abused by the legal system (Deutsch et al., 2017).

Experiences With Emergency Housing

Emergency and temporary housing for IPV survivors are generally available to anyone who requires this form of aid; however, a more critical examination of these services identifies areas where African American women’s socially stigmatized identities may have contributed to their systematic and overt mistreatment. Five studies qualitatively explored African American women’s experiences with shelter workers and found that they overwhelmingly and routinely experienced racist and discriminatory interactions (Few, 2005; Gillum, 2008, 2009; Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013; J. Y. Taylor, 2005). A convergence of the hostile and aggressive Sapphire and the Mammy who is satisfied living in blighted and impoverished conditions may help illuminate African American survivors’ experiences within the emergency shelter system (Givens & Monahan, 2005; Walley-Jean, 2009). These negative depictions may contribute to overall inadequate service provision tailored to meet African American women IPV survivors’ nuanced needs during all phases of emergency housing support (Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013). African American women also experience a range of racial microaggressions (Sue et al., 2007), which is particularly at issue since White workers in IPV shelters are known to systematically overlook African American women’s needs and relegate them to residing in subpar temporary shelters that are located in unsafe neighborhoods where crime and poverty rates are high and where White women are never referred (J. Y. Taylor, 2005). Survivors also noted that providers’ beliefs of their unworthiness extended to their inability to secure adequate social services benefits. African American survivors said that they overwhelmingly felt like the White shelter workers perceived them as less than deserving of any of the emergency benefits that are provided to them (Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013). This lack of worthiness is consistent with the Mammy trope.

Two quantitative studies examined the association between shelter service utilization, interest, and need and found that shelter services are the least likely of the services that abused African American women are likely to utilize, despite needing housing assistance (Anyikwa, 2015; Dichter & Rhodes, 2011). African American women may have internalized a confluence of the Mammy, who is characterized as someone who is unworthy of the same nature and level of treatment as White women, and the SBW because they often withstand derogatory treatment and neglect to report shelter workers when they are mistreated (Few, 2005; Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013). Two qualitative studies examined African American women’s experiences within the shelter system and similarly found that they experience a series of microinvalidations that nullified their experiential realities while residing in the emergency shelter system (Few, 2005; Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013). Yet, these women endured the negative treatment and were hesitant to report their experiences because they feared they would be accused of being too racially sensitive (Few, 2005).

Experiences With the Health Care System

African American women IPV survivors’ experiences with the health care system may result from the Mammy caricature whose needs are routinely overlooked. One study explored women’s help-seeking experiences within health care settings (Paranjape et al., 2007). Paranjape and colleges (2007) conducted six focus groups of 30 African American women, aged 50 and older and found that older IPV survivors are more likely to turn to spiritual sources, specifically clergy and Biblical teachings, rather than rely on medical personnel for assistance because of the barriers that they encountered. Survivors noted they experienced negative interactions with physicians, expressed a suspicion of the healthcare system, and noted that a paucity of age-appropriate resources were available to them. These experiences may point to service providers’ internalized belief that Black women’s needs for adequate medical attention may be overlooked.

An internalization of the SBW and Mammy tropes may be essential to understanding why African American women are likely to forgo engaging with the health care system and neglect to attain timely medical care during their IPV help seeking (Anyikwa, 2015; Fugate et al., 2005; Hamberger et al., 2007; Lucea et al., 2013). Internalized beliefs of self-sufficiency while prioritizing others’ needs may provide insight into this phenomenon (Abramovitz, 1996; Abrams et al., 2014; Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). Although African American women typically seek treatment in the midst of extreme duress, they expect compassionate care (Hamberger et al., 2007; Kaukinen, 2004). However, they are also often faced with navigating a myriad of adverse encounters. According to the Chicago Women’s Health Risk Study, which included a sample 699 women, most of whom were African American, 74% of IPV survivors reported a refusal to seek medical care because of the following barriers: (1) hassle, (2) fear, (3) confidentiality, and (4) tangible loss (Fugate et al., 2005). These barriers also have implications for mental health help seeking, specifically since this population generally seeks mental health services in emergency rooms (Houry et al., 2006).

Experiences With the Mental Health Care System

The Mammy, whose needs may be overlooked and should be relegated to the bottom of the societal hierarchy, and the SBW tropes impact African American women’s experiences with the mental health care system. This is evidenced by mental health clinicians’ discriminatory beliefs that this population is uneducated, unintelligent, and likely to abuse alcohol and illegal drugs (Rodríguez et al., 2009) and their underdiagnoses (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2008; Nicolaidis et al., 2010; Offutt, 2013; Romero, 2000; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Two studies examined African American women’s experiences with providers in the mental health care system (Nicolaidis et al., 2010; Rodríguez et al., 2009). The self-sufficient SBW may have given mental health clinicians permission to overlook African American women’s mental needs. This is reflected in African American women’s low rates of depression diagnoses (Nicolaidis et al., 2010). Further, mental health professionals’ sterile interactions with African American women reflect a lack of cultural awareness and unwittingly communicate a paucity of empathy that leaves them feeling like they do not require the same level of attention and assistance as White women (Evans-Winters, 2019; Nicolaidis et al., 2010).

African American women IPV survivors’ mental health help-seeking experiences are influenced by their internalization of the convergence of the stereotypical SBW who remains strong and resilient and the Mammy who elevates others’ needs above her own even to her own detriment. Three studies analyzed this population’s experiences with service providers and found that they may readily overlook their own mental health needs due to feelings that they can handle anything (Cheng & Lo, 2015; Nicolaidis et al., 2010; Sabri et al., 2013). Notably, African American IPV survivors generally care for others while neglecting to seeking help from mental health professionals, despite experiencing a sequela of poorer mental health outcomes, including suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as other anxiety and mood-related disorders (Carr et al., 2014; Nicolaidis et al., 2010; Rodríguez et al., 2009). In fact, African American women IPV survivors’ internalization of the SBW caricature is evidenced in their preference for alternative mental health treatments, specifically self-care, and may more readily rely upon private and more culturally acceptable forms of assistance, including prayer, meditation, and other forms of religious coping (Nicolaidis et al., 2010; Rodríguez et al., 2009). Despite their heavy reliance upon the Black church during times of crisis, African American women experience barriers within sacred support systems that also necessitate further examination.

Experiences With the Black Church

Four studies collectively found that African American women rely heavily upon religious resources during IPV help seeking (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006; El-Khoury et al., 2004; Nash & Hesterberg, 2009; Potter, 2007). Yet, clergy’s ability to provide necessary assistance may be shrouded by perceptions influenced by the self-sacrificing Mammy and the SBW stereotypes. According to the Pew Research Center, African American women are the most religious population in the United States (Cox & Diamant, 2018). However, clergy have largely neglected to fully support African American women IPV survivors’ needs (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006; Waker-Barnes, 2014). Bent-Goodley and Fowler (2006) conducted a focus group of 19 faith-based leaders and congregants and found that members of clergy used passages of the Bible to encourage survivors to remain with their abusive partner (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006). The church also largely neglects to attend to the trauma experiences of African American women and instead opts to focus on populations it deems as more vulnerable, namely, African American men (Waker-Barnes, 2014). While the phenomenon of exalting the institution of marriage above the needs of abused women may be not specific to the Black church, clergy’s misdirection, compounded by African American women’s over reliance upon their church (Lacey et al., 2020) and religious resources, have had significant adverse implications upon their ability to secure crisis intervention (Bent-Goodley & Stennis, 2015; Violence Policy Center, 2020).

African American women IPV survivors’ internalization of the Mammy and the SBW caricatures may have influenced the ways they interact with the religious community, despite using their religious practice as a form of resistance (Borum, 2012). El-Khoury (2004) and colleagues found that while there are no racial or ethnic differences in religious help seeking, African American women more readily than White women rely upon prayer for strength. Additional emergent themes were women’s reliance upon spirituality and prominent Biblical characters in times of duress while forgoing clergy assistance and intervention (El-Khoury et al., 2004). African American women generally secretly suffer from abuse, garner inner spiritual strength, and more readily rely upon Biblical readings, prayers, and their spirituality for private support rather than securing more public assistance from member of the clergy (Nash & Hesterberg, 2009; Potter, 2007).

Discussion

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to examine how representational intersectionality, specifically the ways that controlling and stereotypical images influence African American women IPV survivors’ help seeking. Intersectionality is a particularly useful framework to illuminate barriers to this population’s help seeking because it provides a lens whereby their overlapping vulnerabilities may be elucidated and how these vulnerabilities impact their ability to secure urgent aid. Race, class, and gender oppression are experienced simultaneously and are inextricably linked (Crenshaw, 1991). It is their compounded effects and the ways in which they reinforce each other that differentiates the needs and experiences of African American survivors. Inherent in this theoretical examination is the relationship of the empowered and the disempowered and how these power differentials intersect to produce complex social inequities that further marginalize the disempowered (Collins, 2019). Similarly, at the core of IPV victimization is power, how it is employed by the perpetrator as well as ways in which it is resisted (Campbell & Mannell, 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Collins, 2019). As such, utilizing intersectionality theory as a framework for analysis is fundamental to more fully understanding African American women IPV survivors’ help-seeking experiences.

Representational intersectionality provides an overarching framework for examining the politics of positionality (Collins, 2019); yet, it falls short of explaining some of the individualistic ways that caricatures and tropes have been normalized, internalized, and are salient to African American women’s ways of navigating the sociological barriers they experience during their IPV help seeking. Employing controlling images extends the intersectional analysis to more fully elucidate some of the barriers erected by individual actors within formal- and quasi-trained systems of support. Controlling images are racist, sexist, and discriminatory caricatures developed during slavery when it was socially acceptable to objectify African American women, relegating them as emotionless, self-sacrificing subhuman beings not worthy of securing the same quality and level of intervention as White women. Exploitative, stereotypical images have been popularized and perpetuated as normative behavior which have been weaponized against African American women and are salient to their daily interactions (Collins, 2002). These images are particularly pernicious for IPV survivors who are forced to navigate additional sociological barriers preventing them from securing immediate assistance from service providers while they are in the midst of crisis (Bent-Goodley, 2013). Tragically, this evidenced pattern of lower level and delayed engagement among African American women survivors of IPV, too often, results in them suffering more lethal and serious injuries (Petrosky et al., 2017; Violence Policy Center, 2020).

This review focused on the sociological barriers that are specific to African American women in the United States. However, racism and racial discrimination are not specific to the United States. Racism is endemic and anti-Blackness racism is a global issue that may impact the nature and level of survivor services that Black women receive (Bledsoe & Wright, 2019; Linos et al., 2014). This phenomenon is evidenced when Whiteness is considered a valuable racial identity that grants White women access to certain social benefits that non-White women may not readily receive (Harris, 1993). Anti-Blackness racism is particularly pernicious when it is experienced by women who are in desperate need for domestic violence survivorship services (Bent-Goodley, 2013; Bledsoe & Wright, 2019; Petrosky et al., 2017). In regions in the world where Black people are in places of governance and power, the availability of domestic violence services is shaped by socially prescribed norms, as well as community and individual factors that may limit women’s access to such services (Campbell & Mannell, 2016; Linos et al., 2014; Logie & Daniel, 2016; Oluwole et al., 2020).

Limitations of Current Literature

Samples that include African American women may not be as readily available, particularly since there is a dearth of literature that centralizes their IPV help-seeking experiences (Robinson et al., 2020). This review is limited by data available via the databases included in this search. Only peer-reviewed publications were included to increase the focus on rigorous studies within the review. Journal publications are biased toward including studies with large effects (Littell et al., 2008), so the authors conducted an additional search among the gray literature via the Cochrane collaboration to account for this bias. However, no additional articles were found. This study was further reliant upon available data that were reported by the study authors, which limit a more thorough analysis. Moreover, studies that employed focus groups as a data collection method may not reflect the breadth of participants’ experiences as IPV survivors often experience stigma and shame resulting from victimization (McLafferty, 2004).

Future Directions

Future research could examine more recent illuminations of the ways that African American women embrace their strengths and resilience during their IPV help seeking, as framed in the Twitter hashtag #BlackGirlMagic (Walton & Oyewuwo-Gassikia, 2017). Created in 2013 by CaShawn Thompson, the handle celebrates the “universal awesomeness of Black women.” Understanding African American women’s more recent forms of resistance to anti-Blackness racism could provide a lens to explore their vulnerabilities, strengths, and resilience. Additional research could focus upon the needs of other subpopulations of African American, namely, sexual minority women and those with a physical or learning disability. Future studies could also examine the IPV help-seeking experiences of subpopulations of Black women, specifically African, Afro Caribbean, Black Latina, and Black European women residing in the United States.

Conclusion

African American women have been routinely objectified, overlooked, experienced overt mistreatment, and had their voices minimized by providers within the very systems that were supposed to assist them. The criminal justice system fails to provide the same deference to African American women as they do White survivors (Few, 2005). Despite calls for systemic change and an integration of anti-Blackness racism into praxis, the criminal justice system relies on its roots grounded in slave codes, Black codes and history of lynching, and continue to disproportionately criminalize African American women IPV survivors, while disavowing their urgent cries for immediate assistance (Brewer & Heitzeg, 2008; Few, 2005; Walton & Oyewuwo-Gassikia, 2017). Women are generally referred to emergency housing by responding officers; however, African American women are not always connected to this service (Few, 2005). If women are referred to the emergency shelter system, they too often continue to receive subpar treatment (Few, 2005; J. Y. Taylor, 2005). Furthermore, African American women routinely experience racial microaggressions and often forgo reporting shelter workers out of fear that they will be accused of being too racially sensitive (Few, 2005; Nnawulezi & Sullivan, 2013).

African American women have been systematically omitted from considerations in intervention development within the health care system—a system that survivors are more likely to engage during severe forms of victimization (Black, 2011). Neglecting to fully consider African American women’s nuanced needs could have deadly consequences and is therefore essential to their survival (Kaukinen, 2004; Petrosky et al., 2017). Conscious and unconscious bias also permeate the mental health system even though clinicians are trained to identify and suspend their own biases during practice (Nicolaidis et al., 2010). Still, these helping practitioners may continue to unwittingly inflict harm upon African American women due to their disregard for more readily incorporating their ways of knowing into practice. Clinicians are taught the value of the objective therapeutic stance, which often includes shaking clients’ hands after a session; however, this is incongruent with African American women’s culture that elevates embracing as a form of acknowledgment and appreciation (Evans-Winters, 2019).

The Black church relies on Biblical teachings while neglecting to fully support the most religious population in its congregation, which could point to the continued decline in church membership (Cox & Diamant, 2018; Diamant & Mohamed, 2018). Neglecting to underscore the values of African American women parishioners, clergy may be unwittingly condoning, supporting, and reinforcing practices that counter teachings of love, honor, and respect (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006). This dissonance between modeling the loving, caring God while at the same time the same minimizing African American women only deteriorates their trust and spirituality (Bent-Goodley & Fowler, 2006), while simultaneously diminishing the utility of liberation theology.

Study Implications

Practice.

Elevate providers’ awareness of implicit anti-Blackness racism via Harvard University’s implicit association test for race.

Mandate routine anti-Blackness racism training for all domestic violence service providers.

Implement survivorship services accountability review boards to identify gaps within local domestic violence service provision units.

Integrate a survivorship-first focused approach to intervention.

Implement hospital layperson training for mental health correlates, including anxiety and depressive disorders.

Develop nationwide clergy training on the dangers and implications of IPV.

Policy.

Increase funding to more fully support domestic violence providers that primarily service African American women.

Implement oversight to understand African American women’s experiences of providers receiving funding, ensuring survivors’ needs are met.

Mandate domestic violence screening within health care settings.

Develop funding for churches to provide domestic violence awareness training within their family and/or women’s ministry groups.

Research.

Conduct additional research is necessary that centralizes the needs of African American women IPV survivors.

Focus on within group differences among subpopulations of Black women, namely African, Afro Caribbean, Afro European, and Black Latinas.

Examine how African American women navigate barriers resulting from racism and racial discrimination to secure urgent assistance.

Conduct research that interrogates the needs of African American women survivors of sexual IPV and/or marital rape.

Analyze providers’ perspectives of African American women survivors’ responses to requiring crisis assistance.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number (R36MH116680).

Author Biographies

Bernadine Y. Waller is an adjunct professor and doctoral candidate at Adelphi University School of Social Work who has completed intensive training on qualitative intersectional methods at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a licensed clinician whose research examines the intersections of intimate partner violence (IPV), service provision, mental health, and help seeking, with a particular focus on African American women. She partnered with the NYC Mayor’s Office to combat domestic and gender-based violence and area churches to collect data for her NIMH-funded dissertation. Her dissertation is designed to develop a theory that explains how African American women survivors navigate their psychosocial barriers during their IPV-related help seeking. Her TEDx Talk, Hindered Help, illuminates common barriers that this underresourced population experiences while seeking urgent need. She has also collaborated with the government in Barbados to conduct an evaluation of their UN women-developed batterer intervention program, Partnership for Peace. She is a former journalist who is now a New York State-licensed therapist who specializes in providing culturally congruent interventions to trauma survivors.

Jalana Harris is a licensed psychotherapist, certified hypnotherapist, certified life coach, and consultant based in New York City. She is a full-time lecturer at Columbia University’s School of Social Work and operates a private practice in NYC, providing therapy and coaching to individuals, couples, and families.

Camille R. Quinn is an assistant professor in the College of Social Work at The Ohio State University. She is a juvenile justice expert and has nearly 20 years’ experience as a clinician and administrator in social and health services. She is a licensed social worker in Illinois and Ohio, which informs her program of research. She conducts mixed methods research with a collaborative spirit to engage community, university, and government partners in her work.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- Abramovitz M (1996). Regulating the lives of women: Social welfare policy from colonial times to the present. South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, & Belgrave FZ (2014). Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: Deepening our understanding of the “‘Strong Black Woman’” schema. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar DD (2012, April 12). Tracing the roots of intersectionality. MR Online https://mronline.org/2012/04/12/aguilar120412-html/ [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- *.Anyikwa VA (2015). The intersections of race and gender in help-seeking strategies among a battered sample of low-income African American women. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(8), 948–959. [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi C, & McNeill T (2016). From cultural competence to cultural consciousness: Transitioning to a critical approach to working across differences in social work. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 25(4), 282–299. 10.1080/15313204.2016.1206494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T (2007). “You have to show strength”: An exploration of gender, race and depression. Gender & Society, 21, 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T (2008). Listening past the lies that make us sick: A voice-centered analysis of strength and depression among Black women. Qualitative Sociologist, 31, 391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T (2009). Behind the mask of the strong black woman. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB (2004). Perceptions of domestic violence: A dialogue with African American women. Health & Social Work, 29(4), 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB (2005). An African-centered approach to domestic violence. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 86(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB (2013). Domestic violence fatality reviews and the African American community. Homicide Studies, 17(4), 375–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bent-Goodley TB, & Fowler DN (2006). Spiritual and religious abuse: Expanding what is known about domestic violence. Affilia, 21(3), 282–295. [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB, & Stennis KB (2015). Intimate partner violence within church communities of African ancestry. In Johnson A (Ed.), Religion and men’s violence against women (pp. 133–148). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC (2011). Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: Implications for clinicians. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 10(10), 1–12. https://doi.org/1559827611410265 [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe A, & Wright WJ (2019). The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(1), 8–26. 10.1177/0263775818805102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borum V (2012). African American women’s perceptions of depression and suicide risk and protection: A womanist exploration. Affilia, 27(3), 316–327. 10.1177/0886109912452401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, & Mahendra RR (2015). Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 2.0. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer RM, & Heitzeg NA (2008). The racialization of crime and punishment: Criminal justice, color-blind racism, and the political economy of the prison industrial complex. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(5), 625–644. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Ver Halen NB, Pencille M, Beatty D, & Contrada RJ (2009). Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttell F, & Ferreira RJ (2020). The hidden disaster of COVID-19: Intimate partner violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S197–S198. 10.1037/tra0000646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, & Mannell J (2016). Conceptualising the agency of highly marginalised women: Intimate partner violence in extreme settings. Global Public Health, 11(1–2), 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr ER, Szymanski DM, Taha F, West LM, & Kaslow NJ (2014). Understanding the link between multiple oppressions and depression among African American women the role of internalization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(2), 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, March 3). Intimate partner violence: Consequences. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- *.Cheng TC, & Lo CC (2015). Racial disparities in intimate partner violence and in seeking help with mental health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(18), 3283–3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (1999). Mammies, matriarchs, and other controlling images. In Kournay J, Sterba J, & Tong R (Eds.), Feminist philosophies (2nd ed., pp. 142–152). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2002). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Cox K, & Diamant J (2018, September 26). Black men are less religious than black women, but more religious than white women and men. Fact Tank: News in the Numbers. www.pewresearch.org. [Google Scholar]

- *.Davies K, Block CR, & Campbell J (2007). Seeking help from the police: Battered women’s decisions and experiences. Criminal Justice Studies, 20(1), 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Degruy Leary J (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome. Uptone Press. [Google Scholar]

- *.Deutsch LS, Resch K, Barber T, Zuckerman Y, Stone JT, & Cerulli C (2017). Bruise documentation, race and barriers to seeking legal relief for intimate partner violence survivors: A retrospective qualitative study. Journal of Family Violence, 32(8), 767–773. 10.1007/s10896-017-9917-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamant J, & Mohamed B (2018, July 20). Black millennials are more religious than other millennials. Fact Tank: News in the Numbers. www.pewresearch.org. [Google Scholar]

- *.Dichter ME, & Rhodes KV (2011). Intimate partner violence survivors’ unmet social service needs. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(5), 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RA, & West LM (2014). Stress and mental health: Moderating role of the strong black woman stereotype. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- *.El-Khoury MY, Dutton MA, Goodman LA, Engel L, Belamaric RJ, & Murphy M (2004). Ethnic differences in battered women’s formal help-seeking strategies: A focus on health, mental health, and spirituality. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(4), 383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Winters VE (2019). Black feminism in qualitative inquiry: A mosaic for writing our daughter’s body. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- *.Few AL (2005). The voices of black and white rural battered women in domestic violence shelters*. Family Relations, 54(4), 488–500. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders-Stepans MB (2000). Alarming racial differences in maternal mortality. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 9(2), 50–51. 10.1624/105812400X87653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Frasier R (2006). Rape myth acceptance and deterrents to rape reporting among women. Dissertation Abstracts International 66 (8-B), 4481. (UMI No. 3184867). [Google Scholar]

- *.Fugate M, Landis L, Riordan K, Naureckas S, & Engel B (2005). Barriers to domestic violence help seeking implications for intervention. Violence Against Women, 11(3), 290–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie MA (1984). The myth of the strong black woman. In Rothenberg PS (Ed.), Feminist frameworks: Alternative theoretical accounts of the relations between women and men (pp. 32–35). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- *.Gillum TL (2008). Community response and needs of African American female survivors of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(1), 39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gillum TL (2009). Improving services to African American survivors of IPV: From the voices of recipients of culturally specific services. Violence Against Women, 15(1), 57–80. 10.1177/1077801208328375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens SMB, & Monahan JL (2005). Priming mammies, jezebels, and other controlling images: An examination of the influence of mediated stereotypes on perceptions of an African American woman. Media Psychology, 7(1), 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson A, & Hayes BE (2018). Help-seeking behaviors of intimate partner violence victims: A cross-national analysis in developing nations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10.1177/0886260518794508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BH (2011). The moderating influence of strength on depression and suicide in African American women [Psychology Dissertations]. Georgia State University, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/psych_diss/107 [Google Scholar]

- Guadalupe-Diaz XL, & Jasinski J (2017). “I wasn’t a priority, I wasn’t a victim” challenges in help seeking for transgender survivors of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 23(6), 772–792. 10.1177/1077801216650288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, & Guse CE (2007). Racial differences in battered women’s experiences and preferences for treatment from physicians. Journal of Family Violence, 22(5), 259–265. 10.1007/s10896-007-9071-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamin DA (2008). Strong black woman cultural construct: Revision and validation [Dissertation]. Georgia State University, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/psych_diss/43 [Google Scholar]

- Harris CI (1993). Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review, 1707–1791. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Lacewell M (2001). No place to rest: African American political attitudes and the myth of black women’s strength. Women & Politics, 23, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, & Oliver MN (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 4296–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe M, & McLaughlin EC (2019). Oklahoma ex-officer convicted of raping multiple women is denied an appeal. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/02/us/holtzclaw-appeal-denied/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Kemball R, Rhodes KV, & Kaslow NJ (2006). Intimate partner violence and mental health symptoms in African American female ED patients. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(4), 444–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VMS (2008). “What, then, is the African American?” African and Afro-Caribbean identities in Black America. Journal of American Ethnic History, 28(1), 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Olivo N, Gibson N, Reed W, & Ashburn-Nardo L (2009). Priming media stereotypes reduces support for social welfare policies: The mediating role of empathy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(4), 463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katznelson I (2005). When affirmative action was white. W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen C (2004). The help-seeking strategies of female violent-crime victims: The direct and conditional effects of race and the victim-offender relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(9), 967–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolivoski KM, Weaver A, & Constance-Huggins M (2014). Critical race theory: Opportunities for application in social work practice and policy. Families in Society, 95(4), 269–276. 10.1606/1044-3894.2014.95.36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey KK, Jiwatram-Negron T, & Sears KP (2020). Help-seeking behaviors and barriers among Black women exposed to severe intimate partner violence: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Violence Against Women. https://doi.org/1077801220917464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey KK, West CM, Matusko N, & Jackson JS (2016). Prevalence and factors associated with severe physical intimate partner violence among US Black women: A comparison of African American and Caribbean Blacks. Violence Against Women, 22(6), 651–670. 10.1177/1077801215610014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurencin CT, & Walker JM (2020). A pandemic on a pandemic: Racism and COVID-19 in Blacks. Cell Systems, 11(1), 9–10. 10.1016/j.cels.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, & Weintraub S (2005). A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1–2), 71–84. 10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linos N, Slopen N, Berkman L, Subramanian SV, & Kawachi I (2014). Predictors of help-seeking behaviour among women exposed to violence in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis to evaluate the impact of contextual and individual factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(3), 211–217. 10.1136/jech-2012-202187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Corcoran J, & Pillai V (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Pocket guides to social work research. Oxford University Press, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Logie CH, & Daniel C (2016). “My body is mine”: Qualitatively exploring agency among internally displaced women participants in a small-group intervention in Leogane, Haiti. Global Public Health, 11(1–2), 122–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lucea MB, Stockman JK, Mana-Ay M, Bertrand D, Callwood GB, Coverston CR, Campbell DW, & Campbell JC (2013). Factors influencing resource use by African American and African Caribbean women disclosing intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(8), 1617–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire DL (2004). “It was like all of us had been raped”: Sexual violence, community mobilization, and the African American freedom struggle. The Journal of American History, 91, 906–931. [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty I (2004). Focus group interviews as a data collecting strategy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(2), 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, & Stewart LA, & the PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash ST (2005). Through Black eyes: African American women’s constructions of their experiences with intimate male partner violence. Violence Against Women, 11(11), 1420–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Nash ST, & Hesterberg L (2009). Biblical framings of and responses to spousal violence in the narratives of abused Christian women. Violence Against Women, 15(3), 340–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson T, Cardemil EV, & Adeoye CT (2016). Rethinking strength black women’s perceptions of the “Strong Black Woman” role. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40, 551–563. [Google Scholar]

- *.Nicolaidis C, Timmons V, Thomas MJ, Waters AS, Wahab S, Mejia A, & Mitchell SR (2010). “You don’t go tell white people nothing”: African American women’s perspectives on the influence of violence and race on depression and depression care. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1470–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Nnawulezi NA, & Sullivan CM (2013). Oppression within safe spaces: Exploring racial microaggressions within domestic violence shelters. Journal of Black Psychology, 40(6), 563–591. 10.1177/0095798413500072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Offutt MR (2013). The strong black woman, depression, and emotional eating [Graduate School Theses and Dissertations].

- Oluwole EO, Onwumelu NC, & Okafor IP (2020). Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence among adult women in an urban community in Lagos, Southwest Nigeria. The Pan African Medical Journal, 36. 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.345.24402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet NM, & Quinn DM (2013). The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 109–122. 10.1080/01973533.2012.746599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmetto N, Davidson LL, & Rickert VI (2013). Predictors of physical intimate partner violence in the lives of young women: Victimization, perpetration, and bidirectional violence. Violence and Victims, 28(1), 103–121. 10.1891/0886-6708.28.1.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Paranjape A, Tucker A, Mckenzie-Mack L, Thompson N, & Kaslow N (2007). Family violence and associated help-seeking behavior among older African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 68(2), 167–172. 10.1016/j.pec.2007.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosky E, Blair JM, Betz CJ, Fowler KA, Jack SP, & Lyons BH (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence—United States, 2003–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(28), 741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim D (2012). Jim Crow museum of racist memorabilia. http://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/

- *.Potter H (2007). Battered black women’s use of religious services and spirituality for assistance in leaving abusive relationships. Violence Against Women, 13(3), 262–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SR, Ravi K, & Voth Schrag RJ (2020). A systematic review of barriers to formal help seeking for adult survivors of IPV in the United States, 2005–2019. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. doi: 10.1177/1524838020916254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M, Valentine JM, Son JB, & Muhammad M (2009). Intimate partner violence and barriers to mental health care for ethnically diverse populations of women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(4), 358–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero RE (2000). The icon of the strong black woman: The paradox of strength. In Greene B (Ed.), Psychotherapy with African American women: Innovations in psychodynamic perspectives and practice (pp. 225–238). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- *.Sabri B, Bolyard R, McFadgion AL, Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Callwood GB, Coverston CR, & Campbell JC (2013). Intimate partner violence, depression, PTSD, and use of mental health resources among ethnically diverse Black women. Social Work in Health Care, 52(4), 351–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soylu Yalcinkaya N, Estrada-Villalta S, & Adams G (2017). The (biological or cultural) essence of essentialism: Implications for policy support among dominant and subordinated groups. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork E (2008). Understanding high-stakes decision making: Constructing a model of the decision to seek shelter from intimate partner violence. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 20(4), 299–327. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Bryant-Davis T, Woodward HE, Tillman S, & Torres SE (2009). Intimate partner violence against African American women: An examination of the socio-cultural context. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(1), 50–58. 10.1016/j.avb.2008.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Taylor JY (2005). No resting place: African American women at the crossroads of violence. Violence Against Women, 11(12), 1473–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KY (2019). Black feminism and the Combahee river collective. Monthly Review-An Independent Socialist Magazine, 70(8), 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- *.Tillman S, Bryant-Davis T, Smith K, & Marks A (2010). Shattering silence: Exploring barriers to disclosure for African American sexual assault survivors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 11(2), 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violence Policy Center. (2020, September). When men murder women: An analysis of 2018 homicide data. Violence Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Barnes C (2014). Too heavy a yoke. Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Waller B (2016). Broken fixes: A systematic analysis of the effectiveness of modern and postmodern interventions utilized to decrease IPV perpetration among Black males remanded to treatment. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 10.1016/j.avb.2016.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walley-Jean JC (2009). Debunking the myth of the “angry black woman”: An exploration of anger in young African American women. Black Women, Gender & Families, 3(2), 68–86. [Google Scholar]