Abstract

Huntington disease (HD) is caused by a pathologic cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeat expansion in the HTT gene. Typical adult-onset disease occurs with a minimum of 40 repeats. With more than 60 CAG repeats, patients can have juvenile-onset disease (jHD), with symptom onset by the age of 20 years. We report a case of a boy with extreme early onset, paternally inherited jHD, with symptom onset between 18 and 24 months. He was found to have 250 to 350 CAG repeats, one of the largest repeat expansions published to date. At initial presentation, he had an ataxic gait, truncal titubation, and speech delay. Magnetic resonance imaging showed cerebellar atrophy. Over time, he continued to regress and became nonverbal, wheelchair-bound, gastrostomy-tube dependent, and increasingly rigid. His young age at presentation and the ethical concerns regarding HD testing in minors delayed his diagnosis.

Keywords: huntington disease, cerebellum, developmental delay, genetics, ethics, MRI

Introduction

Huntington disease (HD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that typically present in the fourth or fifth decade of life with motor, cognitive, and psychiatric disturbances.1 However, 5% to 10% of patients affected by HD will have juvenile-onset disease (jHD), often presenting with an entirely different set of symptoms. Patients with jHD have disease onset by 20 years of age.1 Within jHD there is a rare subset of patients with early onset jHD who have symptom onset by 10 years, with an average age of onset of 4.8 years.2

HD is caused by a pathologic expansion of 40 or more cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats in the HTT (huntingtin) gene. It is well determined that age of disease onset is inversely correlated with the size of the CAG expansion.3,4 Patients with very large trinucleotide repeats can present even earlier than is typical of early onset jHD. We present the case of a boy with initial symptom onset at 18 to 24 months and who was found to have 250 to 350 CAG repeats, one of the largest reported. We discuss how variations in presentation of jHD and ethical concerns about HD testing in minors can contribute to delays in diagnosis of early onset jHD.

Case Report

The patient first presented at 2 years and 9 months old for evaluation of unsteady gait. He was born full term and without complications. A formal developmental assessment at 17 months old was normal for age. However, his mother reported that he steadily declined over the following year. On initial neurologic examination, the patient followed simple commands and had a limited vocabulary of ≈25 words. He had full extraocular movements without nystagmus but had truncal titubation and an ataxic, broad-based gait. His tone, strength, and reflexes were normal. Over the next year, the patient worked with physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy but continued to regress. At 4 years old, he was nonverbal, had poor head control, and had lost the ability to walk. Examination revealed mild hypotonia throughout and hyperreflexia. At 5 years old, a gastrostomy tube was placed due to severe oropharyngeal dysfunction, and his tone had evolved from hypotonia to severe rigidity.

Mother reported a family history of HD in the patient's paternal grandmother. The specifics of her diagnosis were unknown, because the patient's father was incarcerated and unavailable to provide the history. Reportedly, the father had no symptoms of HD and was never tested. A genetic counselor who specialized in HD was contacted after the patient's initial presentation and advised against testing for jHD due to ethical concerns. His presentation was thought to be atypical for jHD due to the young age of symptom onset and testing could potentially reveal an unrelated diagnosis of HD.

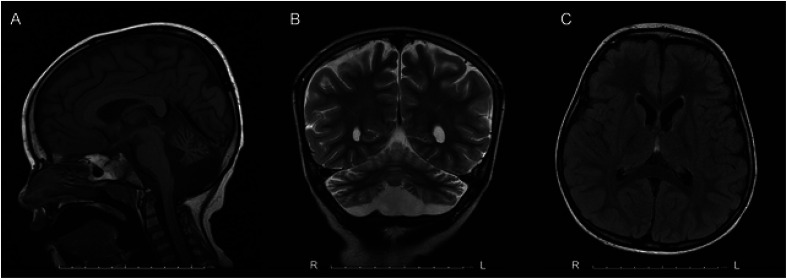

An initial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 3 years old showed moderate atrophy of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis. A repeat brain MRI at 5 years old showed the cerebellar atrophy had progressed from moderate to severe. It also demonstrated mild diffuse cerebral white matter volume loss. There was no evidence of caudate atrophy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MRI brain (A) sagittal T1, (B) coronal T2, and (C) axial T2 fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) of patient at 5 years old showing mild diffuse cerebral white matter volume loss and severe atrophy of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Laboratory evaluation for inborn errors in metabolism was unremarkable. A chromosomal microarray was normal. Alpha-fetoprotein for ataxia telangiectasia and GAA-repeat testing for Friedreich ataxia were normal. Additional workup, including glycosylated transferrin, a spinocerebellar ataxia trinucleotide repeat expansion panel, and whole-exome sequencing and mitochondrial DNA sequencing, was also unremarkable.

At 7 years old, the patient was referred to the closest site of the Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN). While there, the family history of HD, along with the progressive nature of the patient's condition, raised the concern again for jHD. The family received genetic counseling and opted to test for HD. The patient was found to have 250 to 350 CAG repeats. Due to the extremely high expansion number, the lab repeated the assay and verified the results, confirming the diagnosis of jHD in the patient.

The family was counseled about the diagnosis of jHD and the associated genetic risk to relatives. The patient's 9-year-old brother, who had a history of seizures and behavioral issues, had developed dysarthria, gait instability, and increased seizure frequency over the prior year. Testing of the brother revealed 98 CAG repeats, confirming the diagnosis of jHD in a second child in the family.

Discussion

We report a rare case of a young boy with extreme early onset, paternally inherited jHD due to 250 to 350 CAG repeats in the HTT gene. His initial symptom was gait instability, with onset between 18 and 24 months. He continued to decline to the point of becoming nonverbal, wheelchair-bound, gastrostomy-tube dependent, and increasingly rigid by 5 years old. To the best of our knowledge, the individual with the largest number of repeats published to date is that of a girl diagnosed at 3 years old with 265 CAG repeats.5 She had symptom onset at 18 months, with motor and speech delays, and also had paternally inherited disease.

HD is caused by a dominantly inherited pathologic CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion in the HTT gene, which encodes the huntingtin protein. The huntingtin protein abnormally accumulates in neurons, leading to cell death.1 HD appears to have full penetrance with 40 CAG repeats, reduced penetrance with 36 to 39 repeats, increased risk for generational expansion with 27 to 35 repeats, and normal is considered fewer than 27 repeats.1 A higher number of CAG repeats results in both younger age of disease onset and more rapid progression.3,4 Accordingly, patients with jHD typically have more than 60 CAG repeats.6 The repeat expansion number can grow larger with subsequent generations due to anticipation. Accelerated expansion can be seen when inherited through the father due to CAG repeat length instability during spermatogenesis.6

Phenotypic Variation

Adult-onset HD has a relatively well-characterized phenotypic triad with abnormal involuntary movements (often chorea), behavioral changes, and dementia.1 However, jHD is much more variable, particularly for those with early onset jHD, defined as onset by 10 years.2 These young patients can present with cognitive concerns, oropharyngeal dysfunction, gait disturbance, behavioral issues, or seizures.2 For some patients, speech and language delays may precede motor deficits.7 Those with symptom onset after 10 years of age typically present with oropharyngeal dysfunction followed by cognitive decline.2 As patients with jHD progress, they tend to develop parkinsonism with bradykinesia, rigidity, and dystonia rather than chorea.6 This is also known as the Westphal variant.2 The patient in this case followed a similar course but at a younger age and with more rapid progression than is typical.

Many jHD patients will receive care from both pediatric and adult neurologists during their lifetime. To provide the best care to these patients, it is important that physicians are exposed to the phenotypic range of HD during their training.

MRI Findings

HD is characteristically associated with caudate atrophy on brain MRI, with caudate tail atrophy thought to be seen earliest in the disease process.8 However, the patient in this case had only cerebellar atrophy on MRI. Other case reports of patients with early onset jHD have similar MRI findings.5,9,10 There is growing evidence that cerebellar involvement, independent of cerebral, and striatal neuropathology, may play a role in HD symptomatology.11

Delays in Diagnosis

It took over 4 years for the patient to receive his diagnosis of jHD. This is not uncommon. One study found it took an average of 9 ± 6 years from symptom onset to jHD diagnosis.12 The longest delays are seen in children with early onset jHD, likely because the pattern of symptoms is variable and not widely clinically recognized.2 Broad genetic tests commonly used for screening children with developmental delays will miss jHD, because trinucleotide repeat expansions are not evaluated on sequencing-based testing or microarray. Family history also plays an important role in diagnosis. However, complicated social situations can make it difficult to obtain a longitudinal family history, as with this patient.

Ethics of Screening for Juvenile Huntington Disease

There are ethical concerns in testing minors for HD which can also lead to delays in diagnosis. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommend deferring predictive genetic testing for adult-onset conditions in children who are asymptomatic unless early intervention can improve outcomes.13 In this case, the patient was symptomatic at presentation. However, testing for HD was not pursued initially due to ethical concerns about testing a minor for a disease process that is rarely symptomatic at such a young age. There are case reports of young children tested for jHD prematurely due to symptoms later determined to be unrelated, a situation we wished to avoid. Early knowledge of the neurodegenerative disorder can be very difficult for the families.14 In retrospect, testing for jHD should have been reconsidered earlier in this patient's course. Over time though, the patient's developmental regression and rigidity more clearly fit the picture of jHD. He was then counseled, tested, and the diagnosis confirmed.

This in turn confirmed the diagnosis of HD in the patient's father, raising further ethical questions. Attempts were made to contact the father for genetic testing and to then inform and counsel him about the results. However, this was ultimately unsuccessful due to his incarceration.

Undiagnosed Diseases Network

An excellent resource for diagnostically difficult cases is the UDN, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund. The UDN strives to provide answers to patients and families affected by unidentified or rare conditions.15 There are 12 UDN clinical sites around the United States where patients and families can work with physicians, genetic counselors, and scientists to determine next best steps for workup in hopes of finding a diagnosis.

Conclusion

Extreme early onset jHD, with symptom onset prior to 2 years of age, is exceptionally rare. We present the case of a young boy with 250 to 350 CAG repeats, one of the largest reported in the literature to date. Patients with very long CAG repeat lengths can present much earlier than is typical for jHD and with cerebellar atrophy on MRI. Though testing a minor for HD raises ethical questions, it should be considered in the appropriate, symptomatic patient. By adding our case to the literature, we hope to further raise awareness about extreme early onset jHD so patients can more readily be diagnosed.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

ORCID iDs: Ashley A. Moeller https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3442-7382

Meredith R. Golomb https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9707-6735

References

- 1.Caron NS, Wright GEB, Hayden MR. 1998. Oct 23 [Updated 2020 Jun 11]. Huntington disease. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1305/

- 2.Gonzalez-Alegre P, Afifi AK. Clinical characteristics of childhood-onset (juvenile) Huntington disease: report of 12 patients and review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(3):223-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz JL, Moser AD, Nopoulos PC. The association between CAG repeat length and age of onset of juvenile-onset Huntington’s disease. Brain Sci. 2020;10(9):575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keum JW, Shin A, Gillis T, et al. The HTT CAG-expansion mutation determines age at death but not disease duration in Huntington disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(2):287-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milunsky JM, Maher TA, Loose BA, Darras BT, Ito M. XL PCR for the detection of large trinucleotide expansions in juvenile Huntington’s disease. Clin Genet. 2003;64(1):70-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quarrell OW, Nance MA, Nopoulos P, Paulsen JS, Smith JA, Squitieri F. Managing juvenile Huntington’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2013;3(3):1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon G, Kramer J, Zanko A, et al. Speech and language delay are early manifestations of juvenile-onset Huntington disease. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1265-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, Ferrante RJ, Bird ED, Richardson EP, Jr. Neuropathological classification of Huntington’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44(6):559-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedjoudje A, Nicolas G, Goldenberg A, et al. Morphological features in juvenile Huntington disease associated with cerebellar atrophy – magnetic resonance imaging morphometric analysis. Pediatr Radiol. 2018;48(10):1463-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolas G, Devys D, Goldenberg A, et al. Juvenile Huntington disease in an 18-month-old boy revealed by global developmental delay and reduced cerebellar volume. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155a(4):815-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh-Bains MK, Mehrabi NF, Sehji T, et al. Cerebellar degeneration correlates with motor symptoms in Huntington disease. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(3):396-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribaï P, Nguyen K, Hahn-Barma V, et al. Psychiatric and cognitive difficulties as indicators of juvenile Huntington disease onset in 29 patients. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(6):813-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):620-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toufexis M, Gieron-Korthals M. Early testing for Huntington disease in children: pros and cons. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(4):482-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Undiagnosed Diseases Network. @UDNconnect. https://undiagnosed.hms.harvard.edu/. Published 2021. Accessed 4/5/21.