Abstract

Bacterial infections may complicate the course of COVID-19 patients. The rate and predictors of bacterial infections were examined in patients consecutively admitted with COVID-19 at one tertiary hospital in Madrid between March 1st and April 30th, 2020. Among 1594 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, 135 (8.5%) experienced bacterial infectious events, distributed as follows: urinary tract infections (32.6%), bacteremia (31.9%), pneumonia (31.8%), intra-abdominal infections (6.7%) and skin and soft tissue infections (6.7%). Independent predictors of bacterial infections were older age, neurological disease, prior immunosuppression and ICU admission (p < 0.05). Patients with bacterial infections who more frequently received steroids and tocilizumab, progressed to lower Sap02/FiO2 ratios, and experienced more severe ARDS (p < 0.001). The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with bacterial infections as compared to the rest (25% vs 6.7%, respectively; p < 0.001). In multivariate analyses, older age, prior neurological or kidney disease, immunosuppression and ARDS severity were associated with an increased mortality (p < 0.05) while bacterial infections were not. Conversely, the use of steroids or steroids plus tocilizumab did not confer a higher risk of bacterial infections and improved survival rates. Bacterial infections occurred in 8.5% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic. They were not independently associated with increased mortality rates. Baseline COVID-19 severity rather than the incidence of bacterial infections seems to contribute to mortality. When indicated, the use of steroids or steroids plus tocilizumab might improve survival in this population.

Keywords: COVID-19 pneumonia, Bacterial infections, Steroids

Introduction

Already in the middle of 2021, the SARS-CoV-2 infection continues, being the largest health problem worldwide [1]. Since its first outbreak in December 2019 and the official consideration as a pandemic by the WHO, the disease has spread through the world affecting practically every community. COVID-19 disease occurs in several phases in which some patients require hospitalization due to acute respiratory distress (ARDS) after the so-called cytokine storm or cytokine release syndrome [2]. Among different therapeutic options, treatment with corticosteroids and tocilizumab has been widely used with conflicting results for the latter [3–5]. In addition, the use of these immunosuppressants could increase the risk of secondary infections [6, 7]; not to forget that respiratory viral infections may also predispose to bacterial [8].

In the present study, our objective was to describe and analyze the prevalence of bacterial infections and the main risk factors for infections, other than SARS-CoV-2, in patients admitted due to COVID-19 pneumonia during the first period of the pandemic. We analyzed the rate of patients with bacterial infections as well as their impact on OVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Knowing the characteristics of bacterial infections in patients with COVID-19 could help us optimize therapeutic options, and corticosteroids and/or antibiotherapy use in patients at risk.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

This retrospective observational cohort study was performed at Hospital Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, a large tertiary university hospital located in Madrid, one of the most affected regions by COVID-19 during the first wave. The study population consisted of adult patients who were admitted because of interstitial pneumonia due to suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 between March 1st and April 30th, coinciding with lockdown and the first pandemic wave. According to this, both RT-PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and suspected SARS-CoV-2 interstitial pneumonia (in the absence of other causes) were included. Follow-up continued to June 30th, 2020. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital’s Research Ethics Commission. All patients were requested their consent to register their clinical information into a database for epidemiological studies.

Local treatment protocol

During the first pandemic wave, immunosuppressive and antibiotic therapy was protocolized in our center. All patients with interstitial pneumonia received azithromycin and hydroxicloroquine during 3 and 5 days, respectively. Lopinavir/ritonavir was used if the patient presented hypoxemia during the first 10 days after symptom onset while interferon-beta (IFN-β) use was determined by the presence of respiratory insufficiency. Steroids and/or tocilizumab were considered in case of ARDS 7 days after symptom onset and in the absence of data suggestive of bacterial superinfection. Empirical antibiotic therapy with cephalosporins in addition to azithromycin relied on the physician’s criteria for each situation.

Data collection and outcomes

Electronic medical records for all hospital admitted patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were reviewed. The main demographics, the baseline comorbidities including immunosuppression and immunosuppressive treatment, microbiological tests (respiratory samples, urinary antigen test, blood, urine and other sites cultures depending on the foci), immunosuppressive treatment received to treat COVID-19 ARDS and outcomes, were collected directly from the electronic medical records. All data were registered by a primary reviewer and subsequently checked by at least two senior physicians.

Definitions

Immunosuppression was defined either as the presence of hematological disease (active lymphoproliferative, myeloproliferative disorders or bone marrow transplantation), solid organ transplantation, active and disseminated solid organ neoplasm or any condition, including autoimmune disease (e.g., Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Sjögren Syndrome or Inflammatory Bowel Disease…) that had required immunosuppressive treatment for at least 3 months. Immunosuppressive treatment was considered when the patient was either receiving active treatment at the time of admission, including equivalent doses of prednisone above 5 mg, or had received chemotherapy or immunotherapy 6 months before disease onset.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) and its severity were defined according to the Berlin definition [9]. In patients whose partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) was unavailable; SapO2/FiO2 ratio was used to assess ARDS and severity [10]. Mild ARDS was considered when PaO2/FiO2 ratio was > 200 mmHg or SapO2/FiO2 > 235 mmHg, moderate when PaO2/FiO2 ratio was > 100 mmHg or SapO2/FiO2 > 160 mmHg and severe when PaO2/FiO2 ratio was ≤ 100 mmHg.

Bacterial infection was documented as the presence of one of the following: fever or chills in the absence of other etiologies, purulent sputum, catheter swelling, inflammatory diarrhea or abdominal pain, along with microbiologic results including blood and urine cultures, upper and lower respiratory samples, cerebrospinal fluid, urinary antigen tests, intraoperative samples, glutamate dehydrogenase test or Clostridioides toxin in stool test. Bacterial pathogen evaluation in blood, fluids, sputum and other samples was performed according to standard microbiological procedures during hospital admission. In addition, laboratory parameters (neutrophilia or procalcitonin elevation) along with radiological and intraoperative findings were considered, particularly in those patients whose microbiological confirmation was not possible. Every suspected infection and its pathogen were carefully and individually assessed by two senior physicians to determine clinical relevance and to avoid selection bias.

Microorganisms were considered multidrug resistant (MDR) if they were resistant to one or more agents in at least three antibiotic classes (beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, aminoglycosides or sulfamides), while difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR) was defined by the resistance to all first-line agents, including all beta-lactams and fluoroquinolones [11, 12].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed through the mean (standard deviation, SD) for quantitative variables and absolute (and relative) frequencies for the categorical. An univariate analysis was performed comparing those characteristics for patients who suffered bacterial infections vs those who did not, and also between survivors and non-survivors by means of chi-square test in case of categorical variables and Mann–Whitney’s U or Student t-test for numerical variables depending on their distributions and performing the Levène test. Potential confounding variables were entered into two multivariable logistic regression analyses. The objective was to identify factors related with the risk of bacterial infection and mortality, respectively. For all analyses, significance level was defined as a p value below 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM, Spain).

Results

Patients characteristics

A total of 1594 patients admitted because of suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia between March and April 2020 were analyzed. Mean age was 65 years old, 62.1% were male and 87.2% had a positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of admission. Overall, 135 patients (8.5%) developed a bacterial infection during admission (Table 1). Patients with infections were significantly older (mean age 68 vs 64.5, p = 0.007) and presented higher rates of baseline comorbidities as diabetes (27.4% vs 16.7%, p = 0.002), neurological disease (20.7% vs 13.5%, p = 0.021) and kidney disease (13.3% vs 6.4%, p = 0.021). In addition, 28.9% of patients with bacterial infection were immunosuppressed (vs 8.7%, p < 0.0001), being the main causes: autoimmune disease (8.9%), hematological disease (7.4%), solid organ neoplasm (5.9%) and solid organ transplantation (4.4%). As a result, 25.2% of infected individuals were receiving immunosuppressive treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Total N (%) | Bacterial infections | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | |||

| COVID-19 hospitalized patients | 1594 | 135 | 1459 | – |

| Mean age (mean, SD) | 65 (15.0) | 68 (14.3) | 64.5 (14.9) | 0.007 |

| Male sex | 990 (62.1) | 87 (64.4) | 903 (61.9) | Ns |

| High blood pressure | 699 (43.9) | 65 (48.1) | 634 (43.5) | Ns |

| Diabetes mellitus | 281 (17.6) | 37 (27.4) | 244 (16.7) | 0.002 |

| Obesity | 424 (26.6) | 36 (30) | 388 (35.7) | Ns |

| Heart disease | 270 (16.9) | 28 (20.7) | 242 (16.6) | Ns |

| Neurological disease | 225 (14.1) | 28 (20.7) | 197 (13.5) | 0.021 |

| Lung disease | 248 (15.6) | 26 (19.3) | 222 (15.2) | Ns |

| Kidney disease | 112 (7) | 18 (13.3) | 94 (6.4) | 0.003 |

| Liver disease | 48 (3) | 6 (4.4) | 42 (2.9) | Ns |

| Immunosuppression | 166 (10.4) | 39 (28.9) | 127 (8.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Autoimmune disease | 65 (4.1) | 12 (8.9) | 53 (3.6) | 0.01 |

| Solid organ transplantation | 30 (1.9) | 6 (4.4) | 24 (1.6) | 0.036 |

| Hematological disease | 35 (2.2) | 10 (7.4) | 25 (1.7) | 0.000 |

| Solid organ neoplasm | 32 (2) | 8 (5.9) | 24 (1.6) | 0.004 |

| Others | 4 (0.25) | – | – | – |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 139 (8.7) | 34 (25.2) | 105 (7.2) | 0.000 |

| Steroids | 68 (4.3) | 15 (11.1) | 53 (3.6) | 0.000 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 25 (1.6) | 6 (4.4) | 19 (1.3) | 0.005 |

| Mycophenolate | 25 (1.6) | 8 (5.9) | 17 (1.2) | 0.000 |

| Biologicals | 30 (1.9) | 6 (4.4) | 24 (1.6) | 0.022 |

| Chemotherapy | 16 (1) | 6 (4.4) | 10 (0.7) | 0.000 |

| Others | 6 (0.4) | – | – | – |

SD Standard deviation, NS Non-significant

A total of 156 bacterial infections occurred in 135 patients, with significant microbiological isolation in 91.9% of them (Table 2). The main sites of infection were urinary tract (32.6%), lung (31.8%) and bacteremia (31.9%), related to catheter in 67.4% of them. In addition, nine patients (6.7%) presented intra-abdominal or skin and soft tissue infection. Other foci were meningitis, endocarditis, otorhinolaryngologycal site, tuberculosis or septic shock (5.9%).

Table 2.

Bacterial infections in 135 COVID-19 patients. Anatomic site and microorganism

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Site of infection | |

| Lung | 43 (31.8) |

| Community-acquiredy/superinfection | 22/43 (51.2) |

| Nosocomial | 21/43 (48.8) |

| Bacteremia | 43 (31.9) |

| Catheter related | 29/43 (67.4) |

| Primary | 14/43 (32.6) |

| Urinary tract | 44 (32.6) |

| Intra-abdominal | 9 (6.7) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 9 (6.7) |

| Others* | 8 (5.9) |

| Microorganism | |

| Gram-positive cocci | 73 (54.1) |

| MRSA | 11 (8.2) |

| MSSA | 2 (1.5) |

| CNS | 32 (23.7) |

| Enterococci | 34 (25.2) |

| Streptococci | 16 (11.9) |

| Enterobacterales | 40 (29.6) |

| E. Coli | 30 (22.2) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 16 (11.9) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 3 (2.2) |

| Others | 2 (1.5) |

| Non-fermentative gram-negative | 13 (9.6) |

| P. aeruginosa | 12 (8.9) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 4 (3) |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 1 (1) |

| Achromobacter spp. | 1 (1) |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 9 (6.7) |

| Clostridium difficile | 4 (3) |

MRSA Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MSSA Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, CNS Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci

*Included meningitis (2 cases), endocarditis (2 cases), otorhinolaryngology site (2 cases), tuberculosis (1 case), or septic shock from unknown foci (1 case)

Regarding the observed microorganisms, gram-positive cocci were the most frequent isolation (54.1%). On the other hand, gram-negative bacteria were documented in 40 patients (29.6%) while non-fermentative bacteria were identified in 13 patients (9.6%). Species are also shown in Table 2.

MDR were isolated in 26 patients (19.3%); due to E. Coli spp (30.8%), Pseudomonas (15.4%), resistant-staphylococci (15.4%), Stenotrophomonas (15.4%), Enterobacter (7.7%), Klebsiella (7.7%), Achromobacter (3.8%) and Acinetobacter species (3.8%). 63.3% of MDR infections happened in ICU admitted patients. In parallel, Gram-negative-DTR were identified in 18 (13.3%), being E. Coli (27.8%), Stenotrophomonas (22.2%), Pseudomonas (16.7%), Enterobacter (11.1%), Klebsiella (11.1%), Achromobacter (5.5%) and Acinetobacter species (5.5%). 77.8% of these isolates were observed in patients admitted to the ICU.

11 patients had no isolate. Foci were: nosocomial pneumonia (four patients), skin and soft tissue (three patients), urinary tract (two patients), diverticulitis (one patient) and septic shock in an immunosuppressed patient with hematological disease.

Disease severity, treatment and outcomes.

Overall, 90.4% of patients with any bacterial infection have had ARDS in the context of COVID-19 disease vs 74.8% of patients without infectious complications (p < 0.001). In addition, these patients had lower SapO2/FiO2 ratios (198 vs 280, p < 0.001). Consequently, the patients with bacterial infections had more severe ARDS (40.7% vs 5.1%, p < 0.001) when compared with the rest. The immunosuppressive treatment used to treat ARSD was also analyzed. Patients with infections had received more steroids (76.1% vs 56.5%, p < 0.0001) and more tocilizumab (40% vs 16.9%, p < 0.001).

Considering outcomes, patients who had suffered bacterial infection had longer hospital stay (19.5 vs 8.4 days, p < 0.001), had been more frequently admitted to the ICU (40% vs 3.8%, p < 0.001) and ICU stays had been significantly higher (27.2 vs 10.4 days, p < 0.001). In addition, these patients had higher readmission rates after discharge (14.2% vs 4.9%, p < 0.001), 57.9% of them motivated by bacterial infections acquired during first admission. Overall mortality was 15.1%, being significantly higher in patients with bacterial infection (25.03% vs 6.70%, p < 0.001).

Risk factors for bacterial infection

To identify the risk factors associated with bacterial infections in the context of COVID-19, a multivariable analysis was performed considering the patient's baseline characteristics, previous treatments, disease severity and the treatment used for ARDS (Table 3). Independent factors related with bacterial infection were: age (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.04, p = 0.009), neurological disease (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.01–2.82 (p = 0.046)), immunosuppression (OR 4.41, 95% CI 2.76–7.06, p < 0.001) and ICU admission (OR 21.36, 95% CI 13.21–34.55, p < 0.001). Neither steroid nor tocilizumab combined with steroid treatment for ARDS were significantly associated with a higher risk of infection after variable adjustment.

Table 3.

Risk factors for bacterial infections in COVID-19 hospitalized patients

| Univariate analysis* | Multivariate analysis** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Baseline conditions | ||||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.007 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.009 |

| DM | 1.88 (1.26–2.81) | 0.002 | 1.60 (0.99–2.49) | 0.059 |

| Neurological disease | 1.68 (1.08–2.60) | 0.022 | 1.69 (1.01–2.82) | 0.046 |

| Kidney disease | 2.23 (1.30–3.82) | 0.003 | 1.221 (0.64–2.29) | 0.555 |

| Active neoplasm | 2.66 (1.52–4.65) | 0.001 | 1.047 (0.50–2.20) | 0.903 |

| Immunosuppression | 4.26 (2.82–6.45) | < 0.001 | 4.41 (2.76–7.06) | < 0.001 |

| Outcome | ||||

| ARDS | 3.17 (1.77–5.68) | < 0.001 | 1.34 (0.70–2.55) | 0.375 |

| ICU admission | 16.69 (10.80–25.81) | < 0.001 | 21.36 (13.21–34.55) | < 0.001 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Steroids | 2.46 (1.63–3.70) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.55–1.61) | 0.828 |

| Tocilizumab | 3.29 (2.27–4.76) | < 0.001 | 0.66 (0.12–3.75) | 0.636 |

| Steroids* + TocilizumabT | 2.43 (1.66–3.58) | < 0.001 | 1.31 (0.80–2.16) | 0.282 |

Ods ratio, confidence intervals and p-values marked with bold indicate statistically significance

OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, DM Diabetes mellitus, ARDS Acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU Intensive care Unit

T: Product term between steroids and tocilizumab treatment

Mortality risk factors

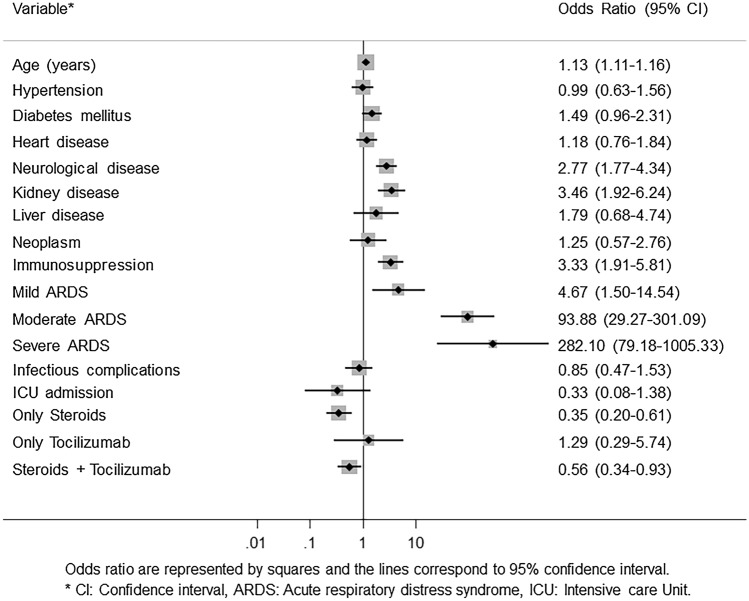

Since a higher proportion of individuals with bacterial infection died during admission in the univariate analysis, a multivariable analysis was performed to identify mortality risk factors (Fig. 1). Mortality was determined by baseline comorbidities, including age (OR 1.13, 95% CI1.10–1.16, p < 0.0001), neurological disease (OR 2.77, 95% CI 1.77–4.34, p < 0.0001), kidney disease (OR 3.46, 95% CI 1.92–6.24, p < 0.0001), previous immunosuppression (OR 3.33, 95% CI 1.91–5.81, p < 0.0001) and by the presence and severity of ARDS: mild ARDS (OR 4.67, 95% CI 1.50–14.54, p = 0.008), moderate ARDS (OR 93.88, 95% CI 29.27–301.08, p < 0.0001) and severe ARDS (OR 282.10, 95% CI 79.18–1005.33), p < 0.0001). By contrast, bacterial infections were not independently associated with mortality (OR 0.85, CI 0.47–1.53, p > 0.05). Steroid treatment (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20–0.60, p < 0.0001) and the combination of steroids with tocilizumab (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.34–0.93, p < 0.024) showed lower mortality rates.

Fig. 1.

Predictors of mortality in COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Odds ratio are represented by squares and the lines correspond to 95% confidence interval. CI Confidence interval, ARDS Acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU Intensive care Unit

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to describe and analyze the burden and risk factors of bacterial infections in patients with COVID-9 disease, since the main therapeutic approaches to date are corticosteroids and tocilizumab, both with recognized potential to develop infections.

We documented a prevalence of 8.5% of bacterial infections, a slightly higher proportion compared to nosocomial and health-care associated infection rates before the pandemic [13, 14]. However, our results are similar to those reported in other COVID-19 cohorts [15, 16]. In addition, we also confirmed that infections are not only caused by respiratory superinfection. There is an important rate of primary and catheter-related bacteremias, urinary tract and abdominal infections, with a significant rate of gram-positive cocci, enterobacterial, non-fermentative and multiresistant pathogens [14, 17, 18]. These are not surprising data since COVID-19 actually can result in long hospital stays, ICU admission, vascular and respiratory devices, malnutrition and a wider use of empirical antibiotherapy, all well-known risk factors for nosocomial infection [19, 20]. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 infection could result in a systemic hyperinflammatory disease that carries a state of immunosuppression beyond lung injury [21, 22], contributing to a significant number of infectious complications affecting other sites.

Our data show that, in addition to age and baseline comorbidities, ICU admission was the main risk factor for the development of bacterial infection. At the same time, ARDS severity and the respiratory worsening of patients during the disease mainly determined ICU admission. Other authors have described significantly higher rates of secondary infections in critically ill patients with severe ARDS [23–25]. Moreover, Bardi et al. identified disease severity as the only factor associated with the development of infection in the ICU [26]. The pandemic situation of the first wave implied a lack of material and staff, infrastructural changes and a significant work overload that altered the normal organization of the ICU. As a result, standards of prophylactic care and aseptic conditions of the procedures were difficult to fulfill as usual, justifying the higher rates of infectious complications.

On the other hand, steroid treatment was initially criticized during the first months of the pandemic since there were no robust evidence to support its use. Several reports informed that early treatment with steroids might extend SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication [27, 28]. In addition, bacterial and opportunistic infections during or after steroid treatment are a major concern and recognized side effect, even at low doses and short courses [6, 29, 30], being a possible limitation for its use in COVID-19 patients. As a matter of fact, Obata et al. found that steroids but not tocilizumab were associated with higher rates of bacterial and fungal infection in COVID-19 hospitalized patients [31]. However, in our cohort neither steroid treatment nor tocilizumab exposure carried a significant risk of bacterial infection when adjusted in the multivariate analysis. Consequently, our study confirms the benefit of the anti-inflammatory effect of steroids in COVID-19, overcoming the potential risk of infections in this scenario [3, 32, 33].

In parallel, similar concerns have affected the use of tocilizumab in autoimmune diseases [7, 34], revealing an even higher risk of bacterial infections with tocilizumab than with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) [35]. In our cohort, tocilizumab use was limited (one or two doses), therefore not conditioning the maintained blockage of IL-6R and avoiding the possible long-term immunosuppression and risk of infection [34]. To note, Stone et al. documented fewer serious infections in patients treated with tocilizumab [4] and the recent trial from Veiga et al. showed no differences in the secondary infection rates when tocilizumab was compared with standard care [5]

Finally, the main related mortality factors were again age, comorbidities and ARDS, while bacterial infections were not an independent factor, reinforcing the hypothesis that infections are a surrogate marker of the most fragile or most severely affected patients with COVID-19. Furthermore, steroid and the combination of steroid with tocilizumab provided a protective effect, supporting its role in COVID-19, since they did not lead to more bacterial infections.

According to our findings, questions about antibiotic therapy during COVID-19 disease arise again. Others have observed that, to date, there is no evidence enough to support empirical antimicrobial due to data absence [36]. In parallel, our results support that antibiotic prescription should not be generalized and might be carefully evaluated; above all if we consider that infections are the consequence of severe disease. Consequently, the best approach seems to be ARDS treatment with clinical and microbiological surveillance; waiting to microbiological definite diagnosis rather than early empirical prescription when suspected.

The main limitation of our study was the absence of data regarding the empirical and targeted antibiotic treatment in the cohort. We were not able to understand their role in the risk and courses of bacterial infections. Unfortunately, and despite that treatment during this period of the pandemic was carefully standardized; no information, conclusions or recommendations could be elucidated in this regard.

In summary, nearly 9% of individuals hospitalized with COVID-19 developed bacterial infection during the first pandemic wave. Although this population exhibited an unfavorable clinical profile, bacterial infections were not independently associated with increased mortality rates or with steroid and tocilizumab treatment for ARDS. This result suggests that bacterial infections reflect disease severity rather than contribute to mortality. Immunosuppressive treatment should be used when indicated given that it did not implied higher bacterial infection rates and resulted beneficial for patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in terms of survival.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Puerta de Hierro COVID-19 working group for their contribution: A. Fernández-Cruz, E. Múñez, R. Malo de Molina, I. Pintos, A. Díaz de Santiago, A. Ramos, P. Mills, P. Laguna, G. Vázquez, M. Valle, A. Muñoz, B. Cantos, J. Calderón, A Ángel-Moreno, I. Baños, E Montero, M. C. Carreño, Y. Romero, R. Muñoz, P. Durán, S. Mellor-Pita, P. Tutor, M. Aguilar, G. Díaz, C. García, B. Jara, R. Laporta, M. T. Lázaro, C. López, P. Mínguez, A. Trisán, R. Carabias, M. Erro, B. Agudo, J. Aller, R. Benlloch, M. R. Blasco, M. A. Brito, V. Calvo, M. Calvo, J. Campos, R. Cazorla, M. Cea, H. Cembrero, E. Colino, S. Córda, S. Cruz, G. Del Pozo, C. Del Pozo, M. Elosua, M. Espinosa, C. Fernández, C. Ferre, M. García-Espantaleón, E. A. García-Izquierdo, B. Gil, P. Gómez-Porro, S. González, I. González, G. Escalera, A. I. López, A. Losa, M. E. Marín, I. Martínez, M. E. Martínez, C. Maximiano, M. Méndez, S. Mingo, C. Mitroi, B. Núñez, P. Ortega, J. F. Oteo, N. Pérez, L. Prieto, L. Relea, G. Rodríguez, J. Sabín, J. Sáenz, A. Sánchez, A. Sánchez, J. Sanz, J. Segovia, L. Silva, J. Toquero, M. E. Velasco, S. Villaverde, A. Andrés, S. Blanco, I. Diego, I. Donate, G. Escudero, E. Expósito, A. Galán, S. García, J. Gómez, A. Gutiérrez, V. Edith, .I Gutiérrez, F. Martínez, A. Mora, I. Morrás, A. Muñoz, A. Valencia, J. M. Vázquez, A. Arias, J. Bilbao, A. M. Duca, M. A. García-Viejo, J. M. Palau, A. Roldán, R. Castejón, M. J. Citores, S. Rosado, J. A. Vargas, P Ussetti.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- DTR

Difficult- to-treat resistance

- HBP

High blood pressure

- MDR

Multidrug resistant bacteria.

- SapO2

Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry

- TNFi

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- FiO2

Fraction of Inspired Oxygen

- ICU

Intensive care Unit

- PaO2

Partial pressure of oxygen

- SOT

Solid organ transplantation

Funding

This work has been supported by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Expedient number PI16-01480).

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Stata v16 software (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our center.

Consent to participate and for publication

Consent was requested for all patients to include their clinical information within a database for epidemiological and clinical studies.

Footnotes

The members of the Puerta de Hierro COVID-19 working group are listed in “Acknowledgements” section.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Víctor Moreno-Torres, Email: victor.moreno.torres.1998@gmail.com.

Carmen de Mendoza, Email: cmendoza.cdm@gmail.com.

the Puerta de Hierro COVID-19 working group:

A. Fernández-Cruz, E. Múñez, R. Malo de Molina, I. Pintos, A. Díaz de Santiago, A. Ramos, P. Mills, P. Laguna, G. Vázquez, M. Valle, A. Muñoz, B. Cantos, J. Calderón, A Ángel-Moreno, I. Baños, E Montero, M. C. Carreño, Y. Romero, R. Muñoz, P. Durán, S. Mellor-Pita, P. Tutor, M. Aguilar, G. Díaz, C. García, B. Jara, R. Laporta, M. T. Lázaro, C. López, P. Mínguez, A. Trisán, R. Carabias, M. Erro, B. Agudo, J. Aller, R. Benlloch, M. R. Blasco, M. A. Brito, V. Calvo, M. Calvo, J. Campos, R. Cazorla, M. Cea, H. Cembrero, E. Colino, S. Córda, S. Cruz, G. Del Pozo, C. Del Pozo, M. Elosua, M. Espinosa, C. Fernández, C. Ferre, M. García-Espantaleón, E. A. García-Izquierdo, B. Gil, P. Gómez-Porro, S. González, I. González, G. Escalera, A. I. López, A. Losa, M. E. Marín, I. Martínez, M. E. Martínez, C. Maximiano, M. Méndez, S. Mingo, C. Mitroi, B. Núñez, P. Ortega, J. F. Oteo, N. Pérez, L. Prieto, L. Relea, G. Rodríguez, J. Sabín, J. Sáenz, A. Sánchez, A. Sánchez, J. Sanz, J. Segovia, L. Silva, J. Toquero, M. E. Velasco, S. Villaverde, A. Andrés, S. Blanco, I. Diego, I. Donate, G. Escudero, E. Expósito, A. Galán, S. García, J. Gómez, A. Gutiérrez, V. Edith, I Gutiérrez, F. Martínez, A. Mora, I. Morrás, A. Muñoz, A. Valencia, J. M. Vázquez, A. Arias, J. Bilbao, A. M. Duca, M. A. García-Viejo, J. M. Palau, A. Roldán, R. Castejón, M. J. Citores, S. Rosado, J. A. Vargas, and P Ussetti

References

- 1.WHO. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Situation Report 62- 5th July 2021 [Internet]. Vol. 2019, WHO Bulletin. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 2.Moore JB, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science. 2020;368:473–474. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, Fernandes AD, Harvey L, Foulkes AS, BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial Investigators et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veiga VC, Prats JAGG, Farias DLC, Rosa RG, Dourado LK, et al. Effect of tocilizumab on clinical outcomes at 15 days in patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;372:n84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George MD, Baker JF, Winthrop K, Hsu JY, Wu Q, Chen L, et al. Risk for serious infection with low-dose glucocorticoids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:870–878. doi: 10.7326/M20-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morel J, Constantin A, Baron G, Dernis E, Flipo RM, Rist S, et al. Risk factors of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab in the French Registry REGATE. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:1746–1754. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanada S, Pirzadeh M, Carver KY, Deng JC. Respiratory viral infection-induced microbiome alterations and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2640. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Ware LB, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Network Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 2007;132:410–417. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadri SS, Adjemian J, Lai YL, Spaulding AB, Ricotta E, Prevots DR, National Institutes of Health Antimicrobial Resistance Outcomes Research Initiative (NIH–ARORI) et al. Difficult-to-treat resistance in gram-negative bacteremia at 173 US Hospitals: retrospective cohort analysis of prevalence, predictors, and outcome of resistance to all first-line agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1803–1814. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikora A, Zahra F. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Nosocomial infections. 2020 Jul 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suetens C, Latour K, Kärki T, Ricchizzi E, Kinross P, Moro ML, The Healthcare-Associated Infections Prevalence Study Group et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections, estimated incidence and composite antimicrobial resistance index in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities: results from two European point prevalence surveys, 2016 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2018;23:1800516. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.46.1800516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V, Lim WS. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D, Quinn J, Pinsky B, Shah NH, Brown I. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. JAMA. 2020;323:2085–2086. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng K, He M, Shu Q, Wu M, Chen C, Xue Y. Analysis of the risk factors for nosocomial bacterial infection in patients with COVID-19 in a Tertiary Hospital. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:2593–2599. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S277963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-García E, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Pouton N, Chumbita M, COVID-19 Researchers Group et al. Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safdar N, Maki DG. The commonality of risk factors for nosocomial colonization and infection with antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, enterococcus, gram-negative bacilli, Clostridium difficile, and Candida. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:834–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-11-200206040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent JL, Bihari DJ, Suter PM, Bruining HA, White J, Nicolas-Chanoin MH, et al. The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) Study. EPIC International Advisory Committee. JAMA. 1995;274:639–644. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530080055041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan. China Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leisman DE, Deutschman CS, Legrand M. Facing COVID-19 in the ICU: vascular dysfunction, thrombosis, and dysregulated inflammation. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1105–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, Leung V, Westwood D, MacFadden DR, et al. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1622–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Wu J, Li Y, Zhou X, Li X, et al. Risks and features of secondary infections in severe and critical ill COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1958–1964. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1812437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giacobbe DR, Battaglini D, Ball L, Brunetti I, Bruzzone B, Codda G, et al. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50:e13319. doi: 10.1111/eci.13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bardi T, Pintado V, Gomez-Rojo M, Escudero-Sanchez R, Azzam Lopez A, Diez-Remesal Y, et al. Nosocomial infections associated to COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: clinical characteristics and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;3:1–8. doi: 10.36519/idcm.2021.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma SQ, Zhang J, Wang YS, Xia J, Liu P, Luo H, et al. Glucocorticoid therapy delays the clearance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in an asymptomatic COVID-19 patient. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2396–2397. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Li W, Jin Y, Xu W, Huang C, Li L, et al. Efficacy evaluation of early, low-dose, short-term corticosteroids in adults hospitalized with non-severe COVID-19 pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:823–836. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00332-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:954–963. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waljee AK, Rogers MA, Lin P, Singal AG, Stein JD, Marks RM, et al. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obata R, Maeda T, Rizk D, Kuno T. Increased Secondary Infection in COVID-19 Patients Treated with Steroids in New York City. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2021;74:307–315. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin DO, Brennan-Rieder D, Ngo B, Kory P, Confalonieri M, Shapiro L, et al. The importance of understanding the stages of COVID-19 in treatment and trials. AIDS Rev. 2021;23:40–47. doi: 10.24875/AIDSRev.200001261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngo BT, Marik P, Kory P, Shapiro L, Thomadsen R, Iglesias J, et al. The time to offer treatments for COVID-19. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2021;30:505–518. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.1901883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grøn KL, Arkema EV, Glintborg B, Mehnert F, Østergaard M, Dreyer L, ARTIS Study Group et al. Risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated in routine care with abatacept, rituximab and tocilizumab in Denmark and Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:320–327. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawar A, Desai RJ, Solomon DH, Santiago Ortiz AJ, Gale S, et al. Risk of serious infections in tocilizumab versus other biologic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multidatabase cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:456–464. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, Ranganathan N, Skolimowska K, Gilchrist M, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2459–2468. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Stata v16 software (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).