Abstract

The highly spreading virus, COVID-19, created a huge need for an accurate and speedy diagnosis method. The famous RT-PCR test is costly and not available for many suspected cases. This article proposes a neurotrophic model to diagnose COVID-19 patients based on their chest X-ray images. The proposed model has five main phases. First, the speeded up robust features (SURF) method is applied to each X-ray image to extract robust invariant features. Second, three sampling algorithms are applied to treat imbalanced dataset. Third, the neutrosophic rule-based classification system is proposed to generate a set of rules based on the three neutrosophic values < T; I; F>, the degrees of truth, indeterminacy falsity. Fourth, a genetic algorithm is applied to select the optimal neutrosophic rules to improve the classification performance. Fifth, in this phase, the classification-based neutrosophic logic is proposed. The testing rule matrix is constructed with no class label, and the goal of this phase is to determine the class label for each testing rule using intersection percentage between testing and training rules. The proposed model is referred to as GNRCS. It is compared with six state-of-the-art classifiers such as multilayer perceptron (MLP), support vector machines (SVM), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), decision tree (DT), naive Bayes (NB), and random forest classifiers (RFC) with quality measures of accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score. The results show that the proposed model is powerful for COVID-19 recognition with high specificity and high sensitivity and less computational complexity. Therefore, the proposed GNRCS model could be used for real-time automatic early recognition of COVID-19.

Keywords: Automated Neurotrophic rule-based, Reduction rule-based, COVID-19, Chest X-Rays images, Neurotrophic classification system

Introduction

Recently, many decision-making problems have received full attention from artificial intelligence and cognitive sciences. Medical diagnosis is considered the most important decision-making problem. It is a procedure for analyzing the relationship between symptoms and diseases based on some information.

Nowadays, this information is usually described as uncertain, incomplete, or inconsistent information, which is very difficult in retrieving, handling, and processing (Thanh et al. 2017; Ali et al. 2016). The neurotrophic set can handle all these problem aspects in information (Ali et al. 2016).

In the last days of 2019, the whole world gets up on the new epidemiological COVID-19, one of the coronaviruses family which is highly spreading. The first cases were reported in Wuhan, China, and they spread to neighborhood countries and then the whole world. Suddenly, the world fights a monster that threatens human lives. This fight has only one weapon, which is science but with a great challenge which is time. The general characteristics of the COVID-19 infected pneumonia are fever, fatigue, dry cough, and dyspnea, which are overlapped with the symptoms of influenza, H1N1, SARS, and MERS. Moreover, these general characteristics are similar to those found in other types of coronavirus syndromes.

The first challenge is to diagnose the patient with COVID-19 accurately. There are several ways of laboratory tests on patientś specimen; the most common is RT-PCR. Unfortunately, this test is expensive, and not all suspected cases can run the test. About 50%–75% of COVID-19 patients have lung abnormalities such as multi-focal ground-glass opacities or peripheral focal based on the early COVID-19 infection. During its early waves of 2020, COVID-19 caused a severe respiratory problems that reached ground-glass opacity and consolidation. According to the CT scans, these symptoms reach their peak 9–13 days (Kanne et al. 2020). CT scans and X-ray images are time-consuming and exhaustive even for expert radiologists.

There is a high need for implementing a medical diagnosis system to analyze the relationship between the symptoms and COVID-19 disease. Modern medical diagnosis problems contain a huge amount of information described by some imprecision, incomplete, vagueness, and inconsistency. However, the poor information and data about the novel COVID-19 and the most symptoms of COVID-19 overlap with symptoms of other diseases. There is a high and urgent need to quickly implement a medical diagnosis system dealing with uncertain, inconsistent, and incomplete information.

Therefore, this research proposes a neutrosophic-based classification model for diagnosing COVID-19 using X-ray images.

Zadeh, in the mid-1960s, put the basis of the fuzzy set (FS) theory to manage vague and imprecise data. In FS theory, every element x belongs to a set A with a membership degree A(x) in [0, 1] (Zadeh 1996). Since FS is used to treat vague data, it could not treat other types of imprecision like incomplete and inconsistent data. Other types of sets have emerged from the FS-like interval-valued FS (Turksen 1986), intuitionistic FS (Atanassov 1989), and interval-valued intuitionistic FS (Atanassov 1989). These newly defined sets cannot handle all aspects of imprecision. Until Smarandache in 1995 defined neutrosophic sets (Smarandache 2002), one theory treats all aspects of imprecision and incompleteness and inconsistency. The neutrosophy concept is capable of dealing with the scope of neutralities (Wang et al. 2005). For an idea, A, the neutrosophy theory considers three terms , and , and the last two terms are together referred to as (Wang et al. 2005). In contrast to fuzzy logic, NL can treat incomplete as well as inconsistent information (Smarandache 2003; Wang et al. 2005)

The fundamental concepts of neutrosophic set (NS) were introduced by Smarandache in (Smarandache 2003) and Alblowi et al. in (Alblowi et al. 2013). The NS came to generalize the concept of FS and all its extensions (Arora et al. 2011).

An element e is represented by the triple e(T; I; F) to mathematically indicate the element’s belongingness to a set as follows: t is its degree of belongingness, i is its indeterminacy , and f is its falsity degree, where t, i, and f take real values in T, I, and F, respectively (Smarandache 2003; Basha et al. 2017).

The sets T, I, and F do not have to be intervals, rather, they may be real values: discrete or continuous; finite or not; union or intersection of various subsets (Smarandache 2003; Basha et al. 2016b). T, I, and F could be dynamically defined as vector functions or operators of set values depending on parameters like: space, time (Smarandache 2003; Hassanien et al. 2018).

T(x), I(x) and F(x): where X is a space of points (objects). There is no constraint on their sum, i.e., . NS operators could be constructed using different ways (Ansari et al. 2013; Basha et al. 2017).

Due to the power of NS to deal with incomplete, inconsistent, and uncertain information, the NS has been applied in different medical applications. For medical diagnosis, Thanh et al. in (Thanh et al. 2017) proposed a clustering algorithm in a neutrosophic advisory system. Also, based on algebraic neutrosophic logic, in (Ali et al. 2016) authors proposed NS recommender system for medical diagnosis application.

Many real-time applications as in (Basha et al. 2016b, 2017, 2019; Anter and Hassenian 2019, 2018; Gaber et al. 2015; Anter et al. 2014) use NS due to its powerful characteristics in treating any type of uncertainty.

The neutrosophic rule-based classification system has three main steps; (a) Neutrosophication: utilized to construct the knowledge-base (KB) model using three neutrosophic membership components; truth, indeterminacy, and falsity. In addition, the membership functions convert the crisp inputs to neutrosophic triple form , (b) Inference Engine: the goal of this stage to get the neutrosophic output by applying the KB and the neutrosophic rules and (c) Deneutrosophication: in this stage, three functions analogous are applied by the neutrosophication to convert the neutrosophic output to a crisp output (Basha et al. 2016b).

On the other hand, SURF is a feature extraction method suggested by Bay et al. (El-gayar et al. 2013). SURF is similar in efficiency to SIFT method and can reduce the computational complexity. SURF detects the robust key points in the images using the Hessian matrix and generates its descriptors. It helps reduce computational cost using an appropriate filter to the integral image. Also, the Haar wavelet responses are calculated to determine the orientation.

Another significant issue is the imbalanced data in real-time applications. In this problem, one class enjoys bigger samples than the other(s). The minority samples tend to get misclassified because the prediction model does not have enough samples of minorities to train the algorithm. The used dataset is imbalanced as shown in Sect. 4.1. Therefore, three different sampling methods are used in our experiments to get balanced samples to solve this problem. Overall, the main contributions to predict patients with COVID-19 based on their chest X-ray images are as follows:

Two experiments are conducted for automated detection of a novel COVID-19 using NRCS and genetic-based NRCS.

Neurotrophic logic is proposed in this application to deal with uncertain and incomplete data.

Different methods are proposed to treat the imbalance data using RUS, ROS, and SMOTE algorithms.

Different experimental results and comparisons are conducted to prove the stability of the proposed GNRCS using various assessments.

The remaining structure of this study is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents some related work. Section 3 presents the background of methods involved and steps of the proposed model. Experimental results and discussion of the results are in Sect. 4. Finally, the conclusion and future work are presented in Sect. 5.

Related work

The spread of the COVID-19 virus motivated many researchers to develop prediction models to help authorities respond rapidly. Modern medical systems depend on X-rays and CT scans for rapid diagnosis. The pneumonia infections in the patients’ images help in this diagnosis.

In (Alam et al. 2021), Alam et al. built a classified COVID-19 patient based on their chest X-ray images. They used histogram-oriented gradient (HOG) and convolutional neural network (CNN).

The authors in (Madaan et al. 2021) also introduced another CNN model, called XCOVNet, for detecting COVID-19 patients in two phases. They used 392 chest X-ray images, half of which are positive and half are negative. First is the pre-processing phase and then training and tuning the model. They started with a handcrafted dataset. Then, a learning rate of 0.001 was used on Adam optimizer.

Also, in (Umer et al. 2021), Umer et al. used CNN for feature extraction of X-ray images. Three filters were applied to form the edges of the images, which helps in reaching the desired segmented target of the infected area in the X-ray images. Deep learning is an intensive data approach, while the datasets of COVID-19 are comparatively small, making it hard for the machine learning approaches to reach robust and generalized results. The Keras Image Data Generator is built for augmenting the taken images. It generated four image classes, one for normal people, another for COVID-19 patients, a third class for virus pneumonia, and finally bacterial pneumonia class. In (Umer et al. 2021), the comparison of the CNN approach against VGG16 and AlexNet in predicting COVID-19 showed that CNN reached competitive results for the normal and bacterial pneumonia classes and identical in the third class.

Albahli and Yar, in (Albahli and Yar 2021), also developed a deep learning multilevel pipeline model for detecting COVID-19 and other chest problems. They used the ImageNet dataset for training. The first classifier in the pipeline checks if the image is COVID-19 or normal or passes it to the second classifier for checking for the other 14 chest problems.

In (Wang et al. 2021), Wang et al. worked on a 1065 CT image taken during the influenza season. The dataset has confirmed COVID-19 cases and others previously diagnosed with viral pneumonia with similar radiologic properties. They also used deep learning to distinguish the COVID-19 cases.

Khan et al. in (Khan et al. 2020), developed a deep CNN model to detect COVID-19-positive cases from X-ray images that contain COVID-19 and other chest pneumonia images. They pre-trained their model on the ImageNet dataset and then trained it on two other datasets.

Ozturk et al., in (Ozturk et al. 2020), developed a model, DarkNet that reached an accuracy of for binary classification (COVID-19 or normal) and accuracy of for three-class classification (COVID or normal or pneumonia). DarkNet was implemented using 17 conventional layers with different filters for each layer.

To distinguish between positive and negative COVID-19 cases, there is a need for alternative methods that extract the most important features from X-ray images. It has been recorded that some learning models face problems like overfitting and tuning hyperparameters. Therefore, metaheuristic learning models have been utilized.

Canayaz in (Canayaz 2021) used feature extraction technique for image contrast enhancement. He used different deep learning models like AlexNet, GoogleNet, VGG19, and ResNet to complete the feature extraction. And he used the metaheuristic algorithms binary PSO and binary gray wolf for optimization. Finally, he used a support vector machine for classification.

Also, in (Kaur et al. 2021), Kaur et al. used AlexNet for feature extraction, and they tuned the hyperparameters using Pareto evolutionary algorithm-II. They tested their model on the four-class dataset (COVID-19, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and healthy).

Neutrosophic set (NS) has many applications in the medical field. Its ability to handle inconsistency and indeterminacy paved the road for using it in the segmentation and the classification of the X-ray, CT, and MRI images (Koundal and Sharma 2019).

Sangeeta and Mrityunjaya in (Siri and Latte 2017) proposed a system of three stages to extract liver images from abdominal CT scans. After the pre-processing stage to remove the noise, they transform CT images into NS images using the three NS membership functions. And finally, in the post-processing phase, they perform a morphological operation on the indeterminacy term to identify the liver boundaries with high accuracy.

Anter and Hassenian, in (Anter and Hassenian 2018), introduced the neutrosophic-based segmentation method for the abdominal CT liver tumor. They used neutrosophic sets (NS), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and a fast fuzzy C-means algorithm (FFCM). They used a median filter first to increase the contrast in the images. Then, domain image was transformed to NS domain. Then, they used FFCM and PSO to optimize the neutrosophic image.

Singh in (Singh 2020) used neutrosophic entropy information in image segmentation. He worked on magnetic resonance (MR) Parkinson’s disease images. He was able to segment the main regions of the MRIs compared to other methods of segmentation of images.

Methods and materials

Feature engineering (FE)

FE is an important step in machine learning models. It extracts the interesting information of an image (features or descriptors) in a series of numbers. A feature—in image processing and computer vision—is a piece of information that carries the content of an image, i.e., interesting parts of images are efficiently captured. For example, a region in an image has certain properties. Features could be certain structures in an image like points, edges, or objects. Ideally, this information is invariant under image transformation. Therefore, the proposed model uses high-performance FE methods (GLCM, fusion, HOG, SURF). Moreover, the feature fusion is applied to show the performance of these features together on the COVID-19 chest X-ray classification problem.

Gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM ) is a powerful method in statistical image analysis. It uses the spatial relationship between pixels. It extracts statistical texture features. This image texture is characterized by calculating how often pairs of pixels (with specific values and in a specified spatial relationship) occur in the image. This is called GLCM. The statistical measures are extracted from this GLCM.

Feature fusion method helps to learn the chest X-ray images’ feature fully. It integrates all information extracted from dataset images without losing any data. The features results from fusion are compact, thus achieving results in better computational complexity.

Histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) is a FE extraction method for object detection. It counts the occurrences of the gradient orientation in a localized portion of an image, i.e., the image is broken down into smaller regions. A histogram is generated for each of these regions using the gradient and the orientation of the pixel values. Then, a gradient histogram of each pixel in the unit cell is collected. Finally, a feature vector is generated by a combination of these histograms. HOG is applied on a dense grid of uniformly spaced regions. It improves accuracy using overlapping local contrast normalization. HOG is widely used in image processing because it is robust to any geometric and optical deformations of images (Tian et al. 2016; Kapoor et al. 2018).

Speeded up robust features (SURF) is a feature extraction-based method for FE. SURF is known to be a fast method and robust. It has proved its superiority over the other FE methods in the proposed model. Therefore, more details of the SURF method are discussed in the following subsection.

Speeded up robust features (SURF)

SURF is a new feature extraction technique for extracting distinctive local features. It uses a local invariant fast keypoint detector to extract important features from an image. SURF is a fast and robust computational feature extraction method that is applied for real-time applications such as object recognition and tracking (Oyallon and Rabin 2015). The main phases of the SURF technique can be described as follows:

Keypoint extraction

Feature points in the image refer to the points in corner, edge, spot, etc. The consistency of the key points can be achieved with the help of repeatability, which is useful for keypoint performance. In the SURF algorithm, the Hessian matrix (HM) is used to speed up the SURF process. By measuring HM, the maximum value point can be calculated. The following equation can be used to define HM at scale to a point in image I:

| 1 |

where is the convolution of Gaussian with image I at point X, and , similarly for and .

In order to increase the speed of the SURF technique, the box filter and integral images are used, which can be calculated based on independent filter size at low computational cost.

Orientation assignment

Haar wavelet is used to specify the orientation of the detected key points. The Haar wavelet responses are measured in x and y directions for a collection of pixels in a circular neighborhood of radius around the detected point. Haar wavelet responses are summed up and determined to determine the dominant orientation within a sliding orientation window of size . Local orientation may be found by summing up all x, y responses for each location in the orientation window. By considering the longest vector between all the windows, the orientation of the interesting point can be determined. SURF is attempting to define a reproducible orientation for the points of interest to be invariant to rotation. To achieve this, the following steps are applied.

The SURF algorithm calculates the Haar-wavelet responses in X- and Y-directions, and this is for a set of pixels in a circular neighborhood of around the specified point. In addition, the sampling step depends on the scale and Haar wavelet responses. As a result, the size of the wavelets is large at high scales. For fast filtering, therefore, integral images are also used.

As a result, the Haar wavelet responses are summed up and measured within the slide orientation window to determine the dominant orientation. Local orientation can be achieved by summing up all the x and y responses in the orientation window at each place. The orientation of the point of interest (PoI) can be specified by defining the longest vector between all the windows.

SURF descriptors

The main goal of the SURF descriptor is to provide concise and robust descriptors of the features. Descriptors may be obtained using the region surrounding the PoI. The SURF features can be determined based on the Haar wavelet responses and the integral images. The following steps are used to extract the descriptor:

The first step is to create a square region clustered around the keypoint and aligned along the direction. This window is set at . This preserves valuable details about spatial information.

Then, the region is divided into a smaller squares regularly and weighted with a Gaussian centered at the PoI to provide some reliability for deformations and translations. For each sub-region, a few simple features are computed at , which are periodically spaced at sample points. For simplicity purposes, we call the Haar wavelet response in the horizontal direction and the Haar wavelet response in vertical direction . The and responses are weighted first with a Gaussian ( based on the key points to boost the effectiveness against geometric deformations and localization errors.

After that, the and wavelet responses are summarized around every sub-region and generate a first group of entries related to the feature vector. We also extract the sum of the absolute values of, and , to carry in details about the polarity of the changes in strength. For its underlying intensity structure, every sub-region has a feature vector V, . These results reflect a feature vector for all sub-regions of 64 in length . These SURF features are invariant due to the lightning invariance of the Haar responses.

Classification system based on neurotrophic rule-based (NRCS)

The proposed NRCS model generalizes the fuzzy rule-based classification system by using neurotrophic logic instead of fuzzy logic (FL). In other words, the premises and conclusion of the “IF-THEN” rules in the NRCS are neurotrophic logic statements instead of FL. The NRCS has three steps as follows.

Neutrosophication. The first stage of our classification model is to convert the crisp inputs to neutrosophic form. Build a neutrosophic knowledge base (KB) constructed using three NL membership functions: truth, indeterminacy, and falsity memberships.

Inference Engine. Firing the “IF-THEN” rules on the KB to generate neutrosophic output.

Deneutrosophication. Converting the neutrosophic output back to crisp one using functions analogous to those in the neutrosophication step.

We explain here more details about the NRCS model.

Information extraction

In this phase, SURF method is used to extract the important features from the X-ray images. In SURF, the first step consists of fixing a reproducible orientation around the key point, based on information from a circular region. Then, in the second step, a squared region containing the selected orientation is constructed to extract the SURF features.

The feature vector of all the sub-regions features is constructed with 64 length values. These SURF features are invariant due to the lightning invariance of the Haar responses. Moreover, the experimental results showed that SURF is a fast computation method and robust for local and invariant representation. It is thus suitable for the real-time COVID-19 diagnosis application.

Neutrosophic-based rules generation phase

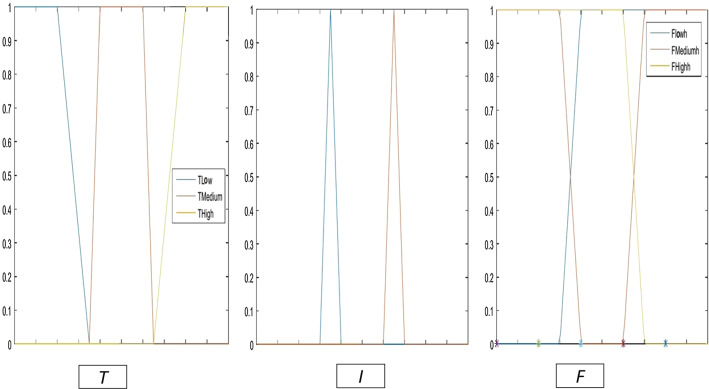

In this phase, the crisp real values in the data set are converted into neutrosophic values using three neutrosophic membership functions as shown in Fig.1. Then, the rules are extracted and converted into neutrosophic form.

Fig. 1.

Truth, indeterminacy, and falsity membership functions

Rule generated numerical example

As a simple example to illustrate the idea of using neutrosophic “IF-Then” rules, consider 8 samples from used dataset as follows (Basha et al. 2019):

0.0086542, −0.0038145, 0.0086542, , 2.04E-03, 0.0015298, Normal

0.006489, −0.00098806, 0.0065901, , 3.48E-03, 0.0018327, Normal

0.0015123, −0.002423, 0.0015123, , 2.98E-03, 0.0011059, Normal

−8.35E-05, 1.31E-05, 8.35E-05, , 7.70E-03, 0.0026105, Normal

0.00065204, −0.0010234, 0.0009464 0.0068657, 0.0022366, Covid

0.00021982, 2.11E-05, 0.00032019 0.0018948, 0.0025601, Covid

0.0014582, −0.00020071, 0.0015333 0.0067872, 0.0019787, Covid

0.0013844, −0.0031614, 0.0013844 0.00059085, 0.00098422, Covid

Divide these samples into training and testing sets and compute the membership degrees of each attribute. Examples of the generated “If-Then” rules for are:

If A=<[High , 0, 0], [High, 0, 0], [High , 0, 0],, [Low , 0, 0],[Medium , 0, 0]>, then B=[Normal].

If A=<[ Low , 0, 0], [ Medium , IndetermincyLowMedium , FalseMedium ], [ Low , 0, 0],, [Low , 0, 0],[ Low , 0, 0]>, then B=[Normal].

If A=<[Low , 0, 0], [High , 0, 0], [Low , 0, 0],, [Medium , IndetermincyLowMedium, FalseMedium ],[ High , 0, 0]>, then B=[Covid].

If A=<[Low , 0, 0], [High , 0, 0], [Low , 0, 0],, [High , 0, 0],[Medium , IndetermincyMediumHigh , FalseMedium ]>, then B=[Covid].

Bio-inspired-based rule reduction phase

In recent years, bio-inspired optimization algorithms have gained popularity in developing robust and competing approaches. They have been used for solving challenging problems Darwish (2018). Genetic bee colony (GBC) algorithm, fish swarm algorithm (FSA), cat swarm optimization (CSO), whale optimization algorithm (WOA), ant lion optimization (ALO), elephant search algorithm (ESA), chicken swarm optimization algorithm (CSOA), moth flame optimization (MFO), and gray wolf optimization (GWO) algorithm are examples of state-of-the-art recent bio-inspired algorithms. Since they mimic animals in looking for food in their random or quasi-random fashion, most of these algorithms incorporate some random element, one of which is the random walk. Where the next move is predicated on only the present location/state and the transition probability to the next place, an animal’s foraging path is practically a random walk Yang (2011).

The genetic algorithm (GA) is a metaheuristic algorithm that inspired the selection process in nature. It depends on the biological inspiration operations: selection, crossover, and mutation. GA is very commonly used in search, and optimization problems generate high-quality solutions.

GA is one of the genetics-based machine learning (GBML) algorithms used as a machine learning tool for generating rule-based classification systems. The most popular GBML approaches are Michigan, and the Pittsburgh approaches (Ishibuchi et al. 2004). They mutually integrate GA with a rule-based system.

Ishibashi and Nascimento in (Ishibashi and Nascimento 2012) combine a GA with a fuzzified rule-based system for classification and adapting parameters of the membership functions. This system can automatically generate fuzzy rules with less human participation.

In (Casillas et al. 2001), J Casillas et al. proposed a method to treat the problem of the exponential growth of the fuzzy rules by increasing the features in the learning process.

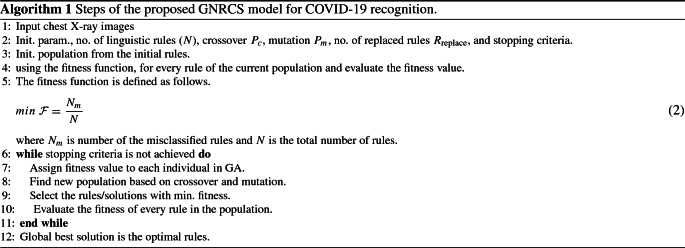

In (Basha et al. 2016a), a new genetic neurotrophic rule-based classification system (GNRCS) is proposed 1.

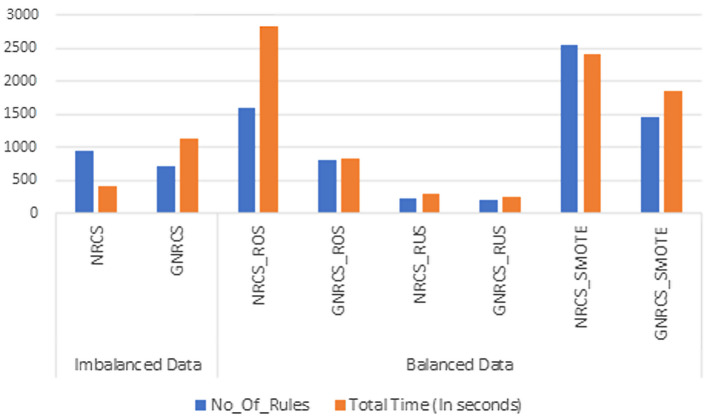

The neurotrophic “IF-THEN” rules generated from the proposed NRCS is then refined in GNRCS. We used the Michigan approach. The classification task in NRCS is improved in GNRCS using GA (Zheng et al. 2021; Mello-Romn and Hernandez 2020; Qiao et al. 2021; Pourrajabian et al. 2021; Kukker and Sharma 2021) to produce the best “If-Then” rules and remove the redundant ones. Algorithm 1 gives a summary of the GNRCS steps and shows the main phases of the proposed GNRCS model.

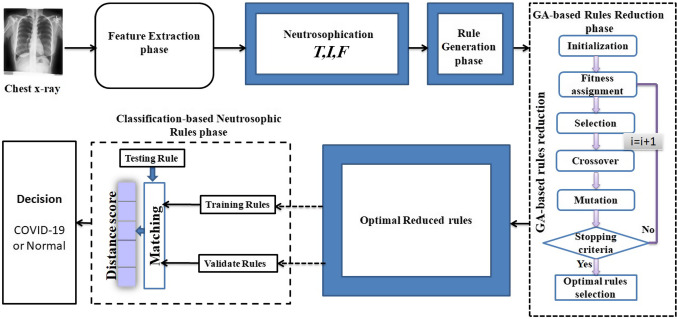

GNRCS-based classification phase

For testing, no classes are provided for the rule matrix to search for one. As in Fig. 2, the intersection percentages between each testing rule () and all the training rules () are calculated, where m is the number of rules in the training set and is the matching percentage between and the training rule . The class label of the testing rule is the same as the one of the training rule with the maximum matching percentage. For any testing rule which does not satisfy an intersection percentage at least 50 with the training rules (), the class label is determined from the exact rules set which have actual class labels. After that, this testing rule is added to the training rules instead of testing rules ().

Fig. 2.

General structure of the proposed GNRCS model

Finally, the testing matrix, which has predicted class labels, is compared with the exact matrix. The confusion matrix is computed, and different metrics can be calculated, such as true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN), to evaluate the proposed model.

The complexity of any rule-based classification system depends directly on the generated rules. And here, we have that the maximum number of rules is the number of objects in the training set. The complexity of our NRBCS is , where N is the number of objects and is the number of extracted features.

Sampling techniques for imbalanced data treatment

One of the most important issues in classification problems is having imbalanced data. This problem comes from an imbalanced distribution of the classes in the given data. In imbalanced datasets, the number of samples in one class (majority) is significantly greater than the number of samples in another class(es) (minority). This results in bias in classification toward the majority class and increases the misclassification rate of the minority class. Many proposed methods deal with imbalanced data, such as (Zheng et al. 2021; He and Garcia 2009; Sun et al. 2007; Tharwat and Gabel 2020). There are three famous sampling methods (He and Garcia 2009).

Random Over-Sampling (ROS): randomly reproducing samples in the minority class to balance the majority class.

Random Under-Sampling (RUS): randomly selecting and removing samples in the majority class to balance the minority class. A simple idea yet results in a higher misclassification rate of the majority class due to the removal of the samples.

Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE): increase the number of the training data of the minority class by generating (not by exact coping) new samples of the minority class relying on the similarities of the current minority samples to balance the samples of the majority class (Tharwat and Gabel 2020).

Experimental results and discussions

We have conducted two experiments. The first explained in Sect. 4.2) targets four goals. The first is to test the NRCS model for automatic detection of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) using different feature extraction methods. The second goal is to test the NRCS model to work with imbalanced and uncertain data sets without any pre-processing steps. The third is to compare the NRCS model and the other conventional ML methods such as MLP (Yamany et al. 2015), SVM, LDA (Tharwat 2016), DT, NS, and RF classifiers. Finally, our fourth goal is to show the strength of the other hybrid proposed model (GNRCS) in improving the NRCS model using GA on our application.

In the second experiment, explained in Sect. 4.3, we have used three sampling methods: RUS, ROS, and SMOTE, in balancing the data to improve the sensitivity to improve the recognition of COVID-19.

Experiments are done using , 2 GB Ram, 250 GB hard drive, and Windows 8.1. All models are self-coded in java. The tenfold cross-validation (CV) is performed, repeated ten times, and the means and the standard deviations of all measures are recorded.

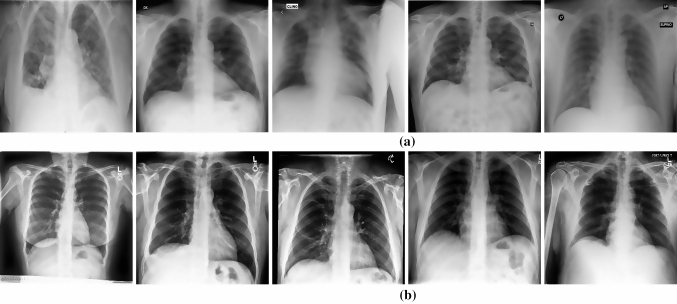

Dataset description

The dataset in this research consists of X-ray images collected from three different open-source repositories for both genders, sharing many characteristics with the same age range ; Github-COVID chest X-ray (Cohen et al. 2020), Kaggle-COVID radiography (A team of researchers from Qatar University Q Doha, the University of Dhaka 2020), and Radiopaedia (Radiopaedie 2020). The three data sets were merged, and redundant images were dropped from the final dataset used. The final dataset consists of 1885 images; 210 of them were for COVID-19 diagnosed cases and the rest 1675 were for normal persons. It is remarkably noticed the few number of the COVID-19 X-ray images. Figure 3 shows sample images of the dataset.

Fig. 3.

Examples of X-ray scans from the merged dataset. a the COVID-19-positive persons. b normal persons

Imbalanced data without any pre-processing and any feature selection method results

In this experiment, we compare the NRCS model against six well-known ML methods: MLP (Yamany et al. 2015), SVM, LDA (Tharwat 2016), DT, Naive_ Bayes (NB), and RF classifiers. The comparisons are in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, precision, specificity, and F-score measures. Table 1 summarizes the results of this experiment. We used the actual imprecise, incomplete, vague, and inconsistent data without applying any features selection method in this experiment.

Table 1.

Results of the proposed NRCS method compared with different ML methods under different measurements criteria

| Metrics | SVM | NB | KNN | DT | MLP | LDA | NRCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.965 | 0.824 | 0.965 | 0.958 | 0.965 | 0.954 | 0.961 |

| Precision | 0.965 | 0.978 | 0.968 | 0.975 | 0.965 | 0.970 | 0.976 |

| Sensitivity | 1.0 | 0.838 | 0.996 | 0.982 | 1.0 | 0.982 | 0.979 |

| Specificity | – | 0.3720 | 0.040 | 0.135 | – | 0.085 | 0.807 |

| F-Score | 0.982 | 0.902 | 0.982 | 0.978 | 0.982 | 0.976 | 0.978 |

Table 1 shows that:

All used methods acquire close accuracy values. Although NRCS recorded the second-best accuracy result after SVM, KNN, and MLP with a small difference, it achieves higher precision and specificity values.

The specificity measure of SVM and MLP is ill-defined due to the data’s imbalanced problem.

The specificity measure reflecting the problem of imbalanced data has a problem all classifiers except NRCS.

Although Naive_ Bayes (NB) gets the worst accuracy among other methods, it achieves the second-best specificity.

Feature extraction based methods

Here, we apply different feature extraction methods GLCM, fusion, HOG, and SURF, to extract the distinctive local important features from images. We compared the results with the ones from the first experiment and summarized that in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between the results by using different feature extraction methods GLCM, fusion, HOG, and SURF

| Measures | GLCM | Fusion | HOG | SURF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 95.8 | 94.2 | 69.9 | 96.1 |

| Precision | 90.1 | 83.8 | 56.9 | 97.6 |

| Sensitivity | 87.9 | 85.9 | 65.7 | 97.9 |

| Specificity | 77.7 | 75.5 | 60.2 | 80.7 |

| F-Score | 88.9 | 84.8 | 60.7 | 97.8 |

From Tables 2 and 3, we can conclude that the SURF feature-extraction method resulted in less number of features and recorded the best results in all measures as well. The decrease in the number of rules extracted by the SURF method has a great impact on the execution time. It resulted in the least time consumed. Therefore, the rest of the experiment will be done using data extracted by the SURF method.

Table 2.

Comparison between the proposed models NRCS and GNRCS

| GLCM | Fusion | HOG | SURF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Extracted Features | 68 | 636 | 500 | 64 |

| Time (Minutes) | 32 | 233 | 150 | 29 |

NRCS vs. GNRCS

Because of their distinct benefits over traditional algorithms (Oteiza et al. 2018; Gupta and Ramteke 2014), they showing very high-quality answers in many complicated real-word problems. This comes due to their ability to address multi-objective optimization problems as well as multi-solution and nonlinear formulations. Many general optimal problems have been successfully solved using evolutionary techniques such as genetic algorithms (GA) and ant lion optimization (ALO).

Here, we enhanced the NRCS model by building a genetic hybrid classification system, GNRCS, for automatic detection of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

While NL in NRCS distinguishes between the most significant, indeterminacy or neutral, and non-significant attributes, the GA is used in refining the neutrosophic rule generated from the NRCS.

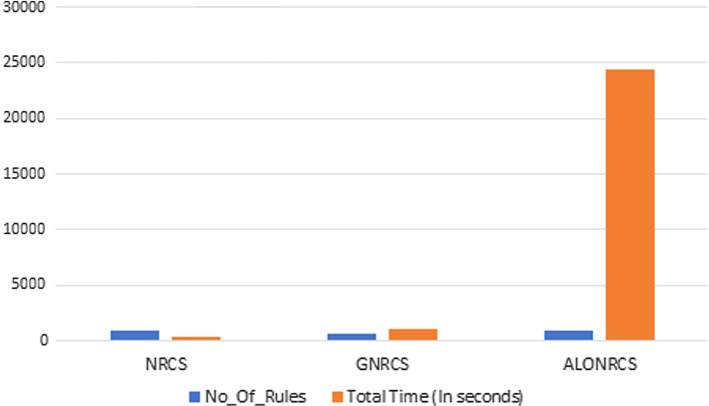

To prove the efficiency of the GA in our case study, an ant lion hybrid classification system combined with NRCS (ALONRCS) was implemented. The results showed that the GNRCS has achieved higher detection accuracy using fewer training rules. Table 4 shows the means and the standard deviations with respect to all measures of the comparisons between NRCS, GNRCS, and the ALONRCS.

Table 4.

Comparison between the proposed models NRCS, GNRCS, and ALONRCS

| Measures | NRCS | GNRCS | ALONRCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.961 (0.52) | 0.9620(0.82) | 0.946(0.012) |

| Precision | 0.976(0.63) | 0.9742(0.82) | 0.952(0.007) |

| Sensitivity | 0.979(0.41) | 0.983(0.63) | 0.989(0.015) |

| Specificity | 0.807(0.42) | 0.78(0.95) | 0.598(0.06) |

| F-Score | 0.978(0.29) | 0.978(0.46) | 0.970(0.007) |

Table 4 shows that:

All models obtained competitive results, though GNRCS showed its superiority.

The proposed GNRCS improves overall the NRCS results. It is very close in the precision and specificity measures.

The hybridization in GNRCS of the genetic and the NS captures the most significant, neutral, and non-significant attributes without using any feature selection methods, which is a result of introducing the indeterminacy term in NL.

The ALONRCS has been more stable showing minimum standard deviations of all measures as a result of its capability to balance exploration and exploitation in the evolution processes.

In GNRCS, GA is used in refining the neutrosophic rules. The results of this experiment show higher accuracy using despite using fewer training rules.

In ALONRCS, ALO is used in refining the neutrosophic rules. The results of this experiment showed very competitive results.

Natural inspired metaheuristics always include random element. They mostly include random walks or some other stochastic factor. Therefore, metaheuristic algorithms frequently employ randomization techniques, and their performance depends on the appropriate use of such randomization (Yang 2014). ALO algorithm consumed very long time which was a nature result of the random ant walking it performs, (Kiliç et al. 2018). Figure 4 shows the dramatic difference in time when using the ant lion algorithm, generating 951 training rules, while the GNRCS still showed its superiority in generating the least number of rules, 707 rules, performed in 1140 sec compared to the ALONRCS generating 951 rules in 24480 sec.

Fig. 4.

Number of rules and total time in seconds in NRCS, GNRCS, and ALONRCS

Treating imbalance in the dataset

As described in Sect. 4.1, the dataset collected is imbalanced. The final merged dataset consists of 1885 images; 210 of them were for COVID-19 diagnosed cases, and the 1675 were for normal persons, which makes the classifier tend to bias in the majority class, ignoring the minority one.

Here, three sampling methods, RUS, ROS, and SMOTE, were conducted to obtain balanced data, namely RUS, ROS, and SMOTE. In the RUS method, the majority of class samples are randomly under-sampled. In the ROS method, the minority class samples are randomly over-sampled. Finally, the SMOTE algorithm increases the minority class by generating new members based on the similarity of existing members of the minority class. Table 5 shows the results of applying the three sampling methods on NRCS and GNRCS. Also Table 6 shows the results using non-parameter statistical test the Wilcoxon rank sum test which is often described as the nonparametric version of the two-sample t-test.

Table 5.

Comparison between NRCS and GNRCS after treating the imbalanced problem using RUS, ROS, and SMOT

| Metrics | NRCS | GNRCS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orig. | RUS | ROS | SMOTE | Orig. | RUS | ROS | SMOTE | |

| Accuracy | 0.961 | 0.9004 | 0.9870 | 0.987 | 0.9620 | 0.8811 | 0.9873 | 0.987 |

| Precision | 0.976 | 0.903 | 1.0 | 0.983 | 0.9742 | 0.8979 | 1.0 | 0.9830 |

| Sensitivity | 0.979 | 0895 | 0.975 | 0.998 | 0.983 | 0.8627 | 0.975 | 0.9982 |

| Specificity | 0.807 | 0.905 | 1.0 | 0.965 | 0.78 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.964 |

| F-Score | 0.978 | 0.899 | 0.987 | 0.991 | 0.978 | 0.88 | 0.9876 | 0.9905 |

Table 6.

Comparison based on Wilcoxon rank sum test between NRCS and GNRCS before and after treating the imbalanced problem using RUS, ROS, and SMOT

| NRCS | GNRCS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUS | ROS | SMOTE | RUS | ROS | SMOTE | |

| p-value | ||||||

| h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

From the results shown in Table 5, we conclude that considering the imbalance in the dataset is important in classification. Although SMOT is famous for balancing data sets—here too, it improves the performance of the models by increasing the sensitivity and the F-score, and ROS algorithm is doing very well in increasing the precision and the specificity without affecting the sensitivity.

From the results shown in Table 6, both the p-value, and h = 1 indicate the rejection of the null hypothesis of equal medians at the default significance level. This means that treating the imbalanced problem using RUS, ROS, and SMOT has significant improvement with both NRCS and GNRCS.

Figure 5 shows the impact of the optimization step (using the GA) on the time with both imbalanced real data and balanced using ROS, RUS, and SMOTE. However, the hybridization step balanced the data and reduced the number of generated rules dramatically. This reduction in rules helped the model to better identify new objects which resulted in improving the results.

Fig. 5.

Number of rules and total time in seconds in NRCS and GNRCS without/with RUS, ROS, and SMOTE

The hybrid model (GNRCS) after treating the imbalance in the dataset resulted in less set of rules and better execution time (Zheng et al. 2021).

Comparison of results

We tested the proposed NRCS model optimized by GA and hybrid ROS, RUS, SMOTE methods—to treat the imbalanced data—against other classification models used for classifying chest X-ray images of COVID-19 patients. Table 7 compares the proposed classification technique with already existing works. All the results show that our proposed model outperforms the other models.

Table 7.

Comparative study with already existing works

| Author | Image size in dataset | Methods | Results in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Zhang et al. 2020) | 532; 506 CT images: 4; 154 positive COVID-19, common pneumonia and normal controls. | two phases: Segmentation and Classification using CNN | Accuracy= 92.49 Sensitivity= 94.93 Specificity= 91.13 |

| (Yasar and Ceylan 2021) | 386 positive Covid-19 and 1010 non-covid | k-NN, SVM, and CNN with 23-layers | Accuracy= 94.73 Sensitivity= 91.97 Specificity= 98.91 F-1 Score= 90.58 |

| (Ardakani et al. 2020) | 510 positive Covid19 and 510 normal | Pre-processing and CNN. | Accuracy= Sensitivity= Specificity= |

| (Apostolopoulos and Tzani 2020) | 1427 images for positive COVID-19 common pneumonia, and normal. | CNN | Accuracy= 96.78 Specificity= 96.46 Sensitivity= 98.66 |

| (Jaiswal et al. 2020) | 1262 positive Covid-19, 1230 normal cases | Different CNN architectures | Accuracy= Sensitivity= Specificity= F-1 Score= . |

| (Han et al. 2020) | 230 positive Covid-19 and 230 normal | C3D, DeCoVNet, AD3D-MIL Algorithm | Accuracy= Sensitivity= F-1 Score= |

| (Zheng et al. 2020) | 540 for positive covid-19 and normal | pre-processing with 2D UNet to form 3D lung mask. NN with three stages: 1- 3D convolution, 2- 3D residual blocks, 3- progressive classifier | Sensitivity= 90.7 Specificity= 91.1 |

| (Pathak et al. 2020) | 413 positive Covid-19 and 439 normal | Different CNN architectures | Accuracy= 93.02 Sensitivity= 91.46 Specificity= 94.78 |

| (Sun et al. 2020) | 2522 of mixed images | adaptive feature selection and Deep forest algorithm | Accuracy= 96.35 Sensitivity= 93.05 Specificity= 89.95. |

| (Nour et al. 2020) | 2905 for positive COVID-19, viral pneumonia and normal. | - Five CNNs for learning and extracting deep feature vectors. - SVM, C4.5 and k-NN classification | Accuracy= 98.75 Sensitivity= 89.39 Specificity= 99.75. |

| (Wang e al. 2020) | 5372 cases. | structure like DenseNet with convolution of multiple stacks | Sensitivity= 78.93 Specificity= 89.93 |

| (Ouyang et al. 2020) | 3389 positive Covid-19 and 1593 normal | Resnet 34 CNN | Accuracy= 87.5 Sensitivity= 86.9 Specificity= 90.1 F-1 Score= 82.0 |

| (Sakagianni et al. 2020) | 349positive Covid-19 and 397 normal | Auto-ML platform (Google Cloud Vision) | Sensitivity= 88.31 F-1 Score= 88.31. |

| (Hu et al. 2020) | 150 positive Covid-19 and 150 normal | Weakly Supervised DL | Accuracy= 90.6 Sensitivity= 83.3 Specificity= 95.6 |

| The proposed | 210 positive COVID-19 and 1675 normal | SURF method to extract features. NRCS and GNRCS are proposed to classifying the COVID-19 patients Different methods are proposed to treat the imbalance data using RUS, ROS, and SMOTE algorithms. | Accuracy=98.7 Sensitivity= 99.8 Specificity= 96.4 F1-Score= 99.05 |

Conclusions and future work

This paper proposes a novel approach to diagnosing COVID-19 patients according to chest X-ray images using neutrosophic logic and genetic algorithms in a rule-based classification system. The dataset was collected from three different publicly accessible repositories. Two novel classification methods are introduced, neutrosophic rule-based classification system and its hybridization with the genetic algorithms for refining the chosen rules. They both are used to generate “If-Then” rules. The proposed approach consists of five main phases. First is the feature extraction phase, where robust features are extracted from X-ray images based on speeded up robust features (SURF) algorithm. Second, to treat imbalanced data sets, three different sampling algorithms are used (SOMTE, ROS, and RUS). This step is essential because the original dataset was imbalanced. Third, classification rules are generated based on neutrosophic logic. The three neutrosophic membership functions (truth, indeterminacy, and falsity) are applied to convert each crisp value to neutrosophic form. Fourth, the genetic algorithm is using for refining the generated neutrosophic rules. It cleans the rules from redundancy and keeps only the most effective ones. The fifth and final stage is recognizing patients with COVID-19. Different experiments were done for evaluating our model, and results showed the superiority of the final model. In general, the results of the proposed models show promising methods in the automatic detection of COVID-19 in the early stages.

As future work, we will focus on obtaining a bigger dataset by collaborating with other hospitals to bring huge cases of COVID-19 with X-ray and CT modalities. Also, we will apply different end-to-end architectures of deep learning methods for feature extraction and classification on this large dataset. More experiments and comparisons will be conducted between the proposed optimization approach and different end-to-end DL approaches. We have found that ant lion is more stable due to its capability to balance exploration and exploitation in the evolution processes; however, its extensive use of random walk consumes too much time. In the future work, we will consider treating the time problem of the ant lion using GPU and have more runs.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this paper declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding its publication.

Footnotes

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: 10.1007/s00500-023-08555-5

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sameh H. Basha and Ahmed M. Anter are Equal Contribution.

Change history

5/22/2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1007/s00500-023-08555-5

Contributor Information

Sameh H. Basha, Email: Samehbasha@Sci.cu.edu.eg

Ahmed M. Anter, Email: Ahmed_Anter@fcis.bsu.edu.eg, Email: Anter@szu.edu.cn

Aboul Ella Hassanien, Email: Aboitcairo@gmail.com.

Areeg Abdalla, Email: Areeg@Sci.cu.edu.eg.

References

- Alam NA, Ahsan M, Based MA, Haider J, Kowalski M (2021) Covid-19 detection from chest x-ray images using feature fusion and deep learning. Sensors 21(4), 10.3390/s21041480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Albahli S, Yar G (2021) Fast and accurate detection of covid-19 along with 14 other chest pathologies using a multi-level classification: Algorithm development and validation study. J Med Internet Res 23. 10.2196/23693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alblowi S, Salama A, Eisa M. New concepts of neutrosophic sets. Int J Math Comput Appl Res (IJMCAR) 2013;3(4):95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Minh N, Son LH. A neutrosophic recommender system for medical diagnosis based on algebraic neutrosophic measures. Appl Soft Comput. 2016;71:1054–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2017.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A, Biswas R, Aggarwal S. Neutrosophic classifier: An extension of fuzzy classifer. Appl Soft Comput. 2013;13(1):563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2012.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anter A, Hassenian A. Computational intelligence optimization approach based on particle swarm optimizer and neutrosophic set for abdominal ct liver tumor segmentation. J Comput Sci. 2018;25:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jocs.2018.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anter AM, Hassenian AE. Ct liver tumor segmentation hybrid approach using neutrosophic sets, fast fuzzy c-means and adaptive watershed algorithm. Artif Intell Med. 2019;97:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anter AM, Hassanien AE, ElSoud MAA, Tolba MF (2014) Neutrosophic sets and fuzzy c-means clustering for improving ct liver image segmentation. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Innovations in Bio-Inspired Computing and Applications IBICA 2014:193–203

- Apostolopoulos I, Tzani M (2020) Covid-19: Automatic detection from x-ray images utilizing transfer learning with convolutional neural networks. Australasian physical and engineering sciences in medicine / supported by the Australasian College of Physical Scientists in Medicine and the Australasian Association of Physical Sciences in Medicine 43. 10.1007/s13246-020-00865-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ardakani A, Kanafi A, Acharya U, Khadem N, Mohammadi A. Application of deep learning technique to manage covid-19 in routine clinical practice using ct images: Results of 10 convolutional neural networks. Comput Biol Med. 2020;121:103795. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora M, Biswas R, Pandy U. Neutrosophic relational database decomposition. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2011;2(8):121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Atanassov KT. More on intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1989;33(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/0165-0114(89)90215-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basha S, Abdalla A, Hassanien AE (2016a) Gnrcs: hybrid classification system based on neutrosophic logic and genetic algorithm. In: Computer Engineering Conference (ICENCO), 2016 12th International, IEEE, pp 53–58

- Basha S, Abdalla A, Hassanien AE (2016b) Nrcs: Neutrosophic rule-based classification system. In: Proceedings of SAI Intelligent Systems Conference, Springer, pp 627–639

- Basha S, Sahlol AT, El Baz SM, Hassanien AE (2017) Neutrosophic rule-based prediction system for assessment of pollution on benthic foraminifera in burullus lagoon in egypt. In: Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES), 2017 12th International Conference on, IEEE, pp 663–668

- Basha SH, Tharwat A, Abdalla A, Hassanien AE. Neutrosophic rule-based prediction system for toxicity effects assessment of biotransformed hepatic drugs. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;121:142–157. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2018.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canayaz M. Mh-covidnet: Diagnosis of covid-19 using deep neural networks and meta-heuristic-based feature selection on x-ray images. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;64:102257. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2020.102257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas J, Cordon O, Del Jesus MJ, Herrera F. Genetic feature selection in a fuzzy rule-based classification system learning process for high dimensional problems. Inf Sci. 2001;136(1–4):135–157. doi: 10.1016/S0020-0255(01)00147-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Morrison P, Dao L, Roth K, Duong T, Ghassemi M (2020) Covid-19 image data collection: Prospective predictions are the future. arXiv:2006.11988. https://github.com/ieee8023/covid-chestxray-dataset

- Darwish A. Bio-inspired computing: Algorithms review, deep analysis, and the scope of applications. Future Comput Inf J. 2018;3(2):231–246. doi: 10.1016/j.fcij.2018.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-gayar M, Soliman H, Meky N. A comparative study of image low level feature extraction algorithms. Egyptian Inf J. 2013;14:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.eij.2013.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber T, Ismail G, Anter A, Soliman M, Ali M, Semary N, Snasel V (2015) Thermogram breast cancer prediction approach based on neutrosophic sets and fuzzy c-means algorithm. 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) pp 4254–4257 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gupta S, Ramteke M. Applications of genetic algorithms in chemical engineering ii: Case studies. Appl Metaheurist Process Eng. 2014 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-06508-3_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Wei B, Hong Y, Li T, Cong J, Zhu X, Wei H, Zhang W. Accurate screening of covid-19 using attention-based deep 3d multiple instance learning. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39(8):2584–2594. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.2996256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanien AE, Basha S, Abdalla A. Generalization of fuzzy c-means based on neutrosophic logic. Stud Inf Control. 2018;27(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- He H, Garcia EA. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2009;21(9):1263–1284. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2008.239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Gao Y, Niu Z, Jiang Y, Li L, Xiao X, Wang M, Fang EF, Menpes-Smith W, Xia J, Ye H, Yang G. Weakly supervised deep learning for covid-19 infection detection and classification from ct images. IEEE Access. 2020;8:118869–118883. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3005510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi R, Nascimento CL (2012) Knowledge extraction using a genetic fuzzy rule-based system with increased interpretability. In: 2012 IEEE 10th International Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), pp 247–252

- Ishibuchi H, Nakashima T, Nii M. Classification and Modeling with Linguistic Information Granules: Advanced Approaches to Linguistic Data Mining (Advanced Information Processing) Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal A, Gianchandani N, Singh N, Kumar N, Kaur M. Classification of the covid-19 infected patients using densenet201 based deep transfer learning. J Biomol Struct Dynam. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1788642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri K, S, Latte MV (2017) Combined endeavor of neutrosophic set and chan-vese model to extract accurate liver image from ct scan. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 151:101–109. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kanne JP, Little BP, Chung JH, Elicker BM, Ketai LH (2020) Essentials for radiologists on covid-19: an updateradiology scientific expert panel. Radiology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kapoor R, Gupta R, Son LH, Jha S, Kumar R. Detection of power quality event using histogram of oriented gradients and support vector machine. Measurement. 2018;120:52–75. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2018.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Chahar V, Singh D, Yadav V, Das N (2021) Metaheuristic-based deep covid-19 screening model from chest x-ray images. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2021. 10.1155/2021/8829829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Shah J, Bhat M (2020) Coronet: A deep neural network for detection and diagnosis of covid-19 from chest x-ray images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 196. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kiliç H, Yuzgec U, Karakuzu C. A novel improved antlion optimizer algorithm and its comparative performance. Neural Comput Appl. 2018;32:3803–3824. doi: 10.1007/s00521-018-3871-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koundal D, Sharma B (2019) 15 - challenges and future directions in neutrosophic set-based medical image analysis. In: Guo Y, Ashour AS (eds) Neutrosophic Set in Medical Image Analysis, Academic Press, pp 313–343, 10.1016/B978-0-12-818148-5.00015-1

- Kukker A, Sharma R. A genetic algorithm assisted fuzzy q-learning epileptic seizure classifier. Comput Electr Eng. 2021;92:107154. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madaan V, Roy A, Gupta C et al (2021) Xcovnet: Chest x-ray image classification for covid-19 early detection using convolutional neural networks. New Generation Comput. 10.1007/s00354-021-00121-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mello-Romn J, Hernandez A (2020) Kpls optimization approach using genetic algorithms. Procedia Computer Science 170:1153–1160, 10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.051,the 11th International Conference on Ambient Systems, Networks and Technologies (ANT) / The 3rd International Conference on Emerging Data and Industry 4.0 (EDI40) / Affiliated Workshops

- Nour M, Cmert Z, Polat K. A novel medical diagnosis model for covid-19 infection detection based on deep features and bayesian optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2020;97:106580. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oteiza PP, Rodr?guez DA, Brignole NB (2018) Parallel cooperative optimization through hyperheuristics. In: Eden MR, Ierapetritou MG, Towler GP (eds) 13th International Symposium on Process Systems Engineering (PSE 2018), Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, vol 44, Elsevier, pp 805–810, 10.1016/B978-0-444-64241-7.50129-4

- Ouyang X, Huo J, Xia L, Shan F, Liu J, Mo Z, Yan F, Ding Z, Yang Q, Song B, Shi F, Yuan H, Wei Y, Cao X, Gao Y, Wu D, Wang Q. Dual-sampling attention network for diagnosis of covid-19 from community acquired pneumonia. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2020 doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.2995508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyallon E, Rabin J. An analysis of the surf method. Image Process Line. 2015;5:176–218. doi: 10.5201/ipol.2015.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk T, Talo M, Yildirim E, Baloglu U, Yildirim O, Acharya U. Automated detection of covid-19 cases using deep neural networks with x-ray images. Comput Biol Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak Y, Shukla P, Tiwari A, Stalin S, Singh S, Shukla P (2020) Deep transfer learning based classification model for covid-19 disease. IRBM. 10.1016/j.irbm.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pourrajabian A, Dehghan M, Rahgozar S. Genetic algorithms for the design and optimization of horizontal axis wind turbine (hawt) blades: A continuous approach or a binary one? Sustainable Energy Technol Assess. 2021;44:101022. doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2021.101022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- A team of researchers from Qatar University Q Doha, the University of Dhaka (2020) Covid19 radiography. https://www.kaggle.com/tawsifurrahman/covid19-radiography-database

- Qiao Z, Minelli G, Noack B, Krajnovi S, Chernoray V. Multi-frequency aerodynamic control of a yawed bluff body optimized with a genetic algorithm. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn. 2021;212:104600. doi: 10.1016/j.jweia.2021.104600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radiopaedie (2020) Radiopaedie. https://radiopaedia.org/

- Sakagianni A, Feretzakis G, Kalles D, Koufopoulou C, Kaldis V (2020) Setting up an easy-to-use machine learning pipeline for medical decision support: Case study for covid-19 diagnosis based on deep learning with ct scans. vol 272, 10.3233/SHTI200481 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Singh P. A neutrosophic-entropy based adaptive thresholding segmentation algorithm: A special application in mr images of parkinson‘s disease. Artif Intell Med. 2020;104:101838. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2020.101838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache F. Neutrosophy, a new branch of philosophy. Multiple-Valued Logic. 2002;8(3):297–384. [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache F (2003) A Unifying Field in Logics: Neutrosophic Logic. Infinite Study, Neutrosophy, Neutrosophic Set, Neutrosophic Probability and Statistics

- Sun L, Mo Z, Yan F, Xia L, Shan F, Ding Z, Shao W, Shi F, Yuan H, Jiang H, Wu D, Wei Y, Gao Y, Gao W, Sui H, Zhang D. Adaptive feature selection guided deep forest for covid-19 classification with chest ct. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020;24(10):2798–2805. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2020.3019505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Kamel MS, Wong A, Wang Y. Cost-sensitive boosting for classification of imbalanced data. Pattern Recogn. 2007;40:3358–3378. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2007.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thanh ND, Ali M, Son LH. A novel clustering algorithm in a neutrosophic recommender system for medical diagnosis. Cogn Comput. 2017;9:526–544. doi: 10.1007/s12559-017-9462-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tharwat A. Linear vs. quadratic discriminant analysis classifier: a tutorial. Int J Appl Pattern Recognit. 2016;3(2):145–180. doi: 10.1504/IJAPR.2016.079050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tharwat A, Gabel T. Parameters optimization of support vector machines for imbalanced data using social ski driver algorithm. Neural Comput Appl. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00521-019-04159-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S, Bhattacharya U, Lu S, Su B, Wang Q, Wei X, Lu Y, Tan C. Multilingual scene character recognition with co-occurrence of histogram of oriented gradients. Pattern Recogn. 2016;51:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2015.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turksen IB. Interval valued fuzzy sets based on normal forms. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986;20(2):191–210. doi: 10.1016/0165-0114(86)90077-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umer M, Ashraf I, Ullah S et al (2021) Covinet: a convolutional neural network approach for predicting covid-19 from chest x-ray images. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing. 10.1007/s12652-021-02917-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Smarandache F, Sunderraman R, Zhang YQ (2005) interval neutrosophic sets and logic: theory and applications in computing: Theory and applications in computing, vol 5. Infinite Study

- Wang S, Kang B, Ma J, Zeng X, Xiao M, Guo J, Cai M, Yang J, Li Y, Meng X, Xu B (2021) A deep learning algorithm using ct images to screen for corona virus disease (covid-19). European radiology pp 1–9, 10.1007/s00330-021-07715-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Lu X, Liu J, Li X, Hu R, Meng X, Dou S, Hao H, Zhao X, Hu W, Gao Y, Wang Z, Lu G, Yan FR (2020) Precise pulmonary scanning and reducing medical radiation exposure by developing a clinically applicable intelligent ct system: Towards improving patient care. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3520032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yamany W, Tharwat A, Hassanin MF, Gaber T, Hassanien AE, Kim TH (2015) A new multi-layer perceptrons trainer based on ant lion optimization algorithm. In: Fourth International Conference on Information Science and Industrial Applications (ISI), IEEE, pp 40–45

- Yang X (2011) Metaheuristic Optimization: Algorithm Analysis and Open Problems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6630. Springer. 10.1007/978-3-642-20662-7_2

- Yang XS (2014) Random Walks and Optimization, pp 45–65. 10.1016/B978-0-12-416743-8.00003-8

- Yasar H, Ceylan M (2021) A novel comparative study for detection of covid-19 on ct lung images using texture analysis, machine learning, and deep learning methods. Multimedia Tools and Applications 80. 10.1007/s11042-020-09894-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zadeh A (1996) Fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets, Fuzzy Logic. And Fuzzy Systems, Selected Papers by Lotfi A Zadeh, World Scientific, pp 394–432

- Zhang K, Liu X, Shen J, Li Z, Sang Y, Wu X, Zha Y, Liang W, Wang C, Wang K, Ye L, Gao M, Zhou Z, Li L, Wang J, Yang Z, Cai H, Xu J, Yang L, Wang G. Clinically applicable ai system for accurate diagnosis, quantitative measurements, and prognosis of covid-19 pneumonia using computed tomography. Cell. 2020;182:1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Deng X, Fu Q, Zhou Q, Feng J, Ma H, Liu W, Wang X (2020) Deep learning-based detection for covid-19 from chest ct using weak label 10.1101/2020.03.12.20027185

- Zheng M, Li T, Sun L, Wang T, Jie B, Yang W, Tang M, Lv C. An automatic sampling ratio detection method based on genetic algorithm for imbalanced data classification. Knowl-Based Syst. 2021;216:106800. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2021.106800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]