Introduction

Women are underrepresented in research describing the health impact of refugee migration. Due to vulnerable positioning within communities impacted by war, women may experience poor health outcomes because of restricted access to health, legal, and economic resources.1 Gender-based torture inheres significant and distinctive mental and physical health consequences.2 In comparison to men, refugee women are at greater risk of social isolation, low self-esteem, and loneliness.3–6 Social support is a critically important protective factor for women refugees, but may be compromised through migration transitions.7–8 An expanding body of evidence suggests that refugee maternal caregiver experiences of torture and trauma impact the health outcomes of youth and families. These intersectional issues reflect active and important disparities experienced by women with refugee status, and highlight an urgent need to be attentive to the voices of women with refugee status as well as seek novel strategies grounded within their unique perspectives, emphasizing optimal health through pathways of resilience. This background led the research team to a study of intergenerational trauma and examination of key relationships between refugee maternal caregiver exposure to war trauma and torture, parent mental health, parent physical health, and youth adjustment. The current analysis is situated within this larger project. The purpose of the analysis presented here was to explore the physical and sensory memories and experiences that were prominent in the remembering and retelling of the trauma narratives of Karen women with refugee status living in the United States post-resettlement.

Background

A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution, war, or violence, fundamental factors often compelling the decision to leave behind their community of origin.9 Since 2009, the United States has resettled approximately 140,000 refugees from Burma (Myanmar).10 Thailand continues to host 99,000 refugees from Burma in nine camps, the majority of which (83%) are Karen ethnicity.11 The World Bank reports that refugees spend a median of five years and an average of 10.3 years in displacement, or before a durable solution to displacement is established. 12 In that time, war-affected families often undergo significant changes that perpetuate or introduce new challenges as a result of the destabilization of borders.

Karen people comprise a large ethnic group originating from Burma, the largest country in mainland Southeast Asia. As a result of a violent and protracted civil war, Karen refugees from Burma report high rates of individual and collective war traumas, including human rights violations, extreme trauma, and torture.13,14 Human rights violations are significant infractions to nonnegotiable rights of all human beings that threaten dignity and equality, defined in the United Nations in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.15 Documented human rights violations endured historically by Karen refugees from Burma include: torture, extrajudicial killing, enslavement, burning of villages, forced migration, forced labor, persecution, extortion, and rape.16–18 At the time of the submission of this manuscript, another military coup was in process in Burma.19 While the narratives presented here describe historical events, the somatic experiences exist in the present day for these women, elicited in response to reminders of the past.

Context of the Analysis

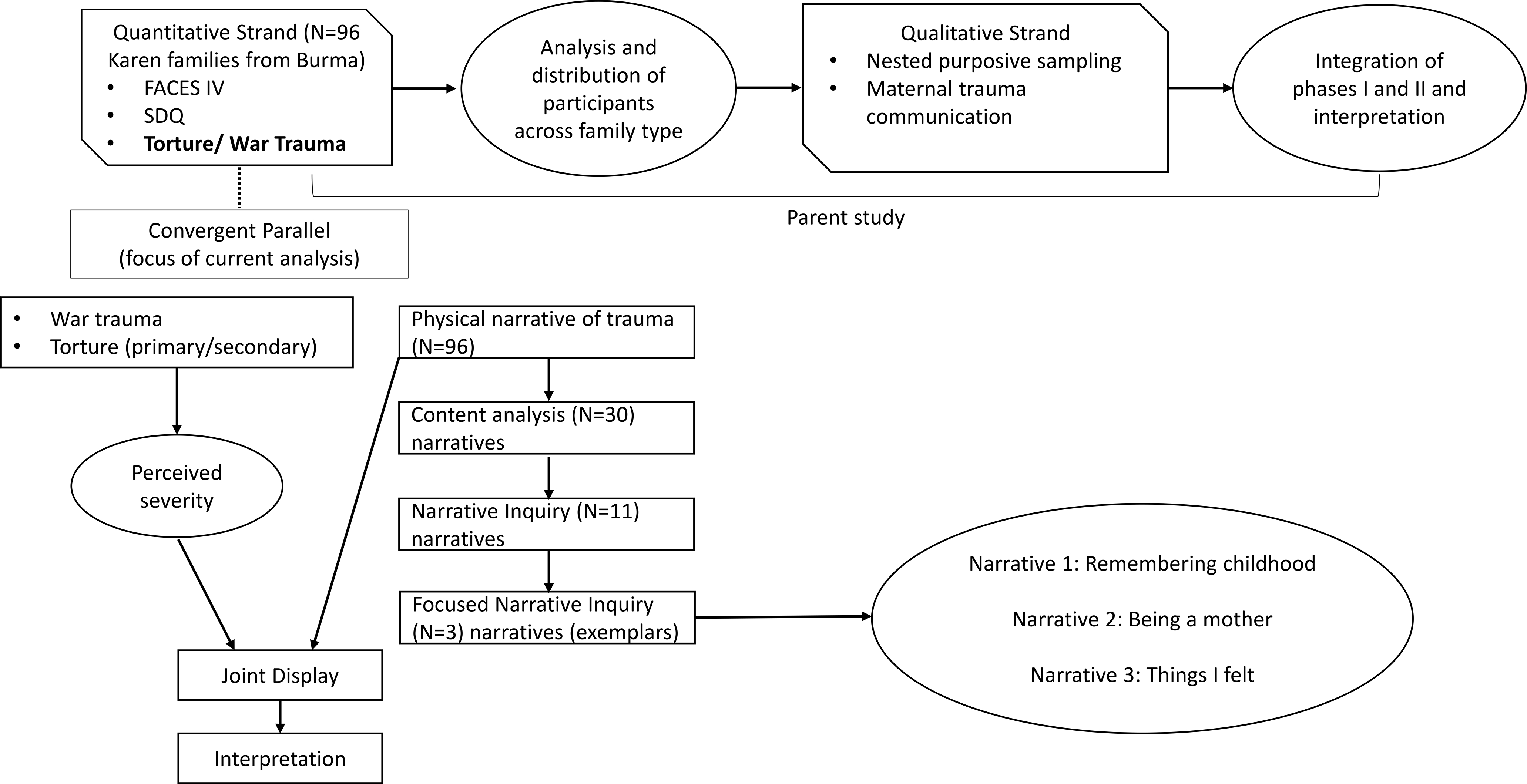

This embedded convergent parallel analysis is part of a larger explanatory mixed methods study that examined associations between parent war trauma and torture, parent mental health distress, and parent physical health problems with youth adjustment (Figure 1).13 The design was contextualized within an overarching theoretical perspective relevant to the ways in which war-affected families collectively process trauma.

Figure 1.

Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods parent study with Embedded Convergent Parallel Data (focus of current analysis).

In the larger explanatory mixed methods project, the study team administered a structured assessment to participants with the objective of characterizing self-reported torture and war trauma experiences in war. Using the General War Trauma and Torture Scale18, the PI posed structured questions to participants to discern a key variable under study (torture status). The study team then coded self-reported war experiences as primary torture, secondary torture, and/or war trauma. The study team did not anticipate the extent to which women participants would elaborate on their experiences, reconstructing portions of their trauma narratives. The data on which authors based this analysis were documented through extensive field notes, conceptualized in this analysis as small stories, or small moments of narrative in which the identity of the speaker becomes the focus of the framework.20

These small stories emerged holistically and functioned to place a context around women’s responses to closed-ended questions. As the narratives unexpectedly emerged, investigators took extensive field notes. Initially, this was done from necessity because of the absence of a recording device. As the research team discussed an approach to these data, it was determined that introducing a recorder would be too invasive, and likely change the nature of the disclosures. Field documentation captured utterances of women verbatim, to the extent possible. The interviewer oriented written documentation of the participant’s responses next to the instrument item that a compelled the participant to elaborate on her experiences beyond the bounds of the question.

Theoretical Framework

Integral to this analysis is Feminist Borderlands Theory, which conceptualizes the redistribution of power from people benefiting from borders to those impacted by them.21,22 Borders benefit people in authority as they are positioned to perpetuate power through policy and regulations that impact the marginalized.23 Through the lens of this theory, the study team framed ways that the retelling of experiences in war acknowledged the complex layers of isolation, power, and control, thus allowing space for re-prioritization of women’s experience.23 Critical engagement with the concept of borders is relevant to the interpretation of trauma narratives. Women with refugee status construct identity within spaces of cultural difference.24 These spaces of difference are more pronounced when they exist along borders – imposed borders, lines or fences delineating a border between countries; or perceived – borders that exist at the margins of ‘other’; or us/them dichotomies. In the context of war and the prolonged migration, Karen women have experienced gendered expectations of behavior that normalize power differentials. Gendered violence threatens borders relative to the physical body. As women reconstructed their trauma narratives, they claimed those narratives by redefining borders that surround the remembering and retelling of the experiences they chose to communicate.

Methods

Authors report findings from an embedded convergent parallel analysis. From a sample of 96 participant encounters, the study team examined the most detailed narratives elicited by questions on the General War Trauma and Torture Scale18. Study activities and procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Sample and Recruitment

The larger study sample included 96 Karen refugee maternal caregivers from Burma living post-resettlement in the United States with primary caregiving responsibility for youth between the ages of 11 and 23 years.13 All participants were resettled to the United States (US) through the US Refugee Admissions Program at least one year prior to the study. Participant recruitment was facilitated by the Karen Organization of Minnesota, a local resettlement organization supporting the wellbeing of refugees from Burma. The primary recruitment source were community partner programs focused on the needs of families with adolescent and young adult Karen youth.

Data Collection

Women participants were Karen-speaking only; a skilled bilingual/bicultural interpreter with specialized training in supporting survivors of torture and war trauma facilitated all study interactions, alongside the interviewer/PI. The research team spent more than 300 hours interacting with study participants within their home environments over the course of the study. The field narratives examined in this analysis were a portion of the full encounter with the participant and ranged in time from 10–40 minutes. These narratives occurred spontaneously in response to questions from the General War Trauma and Torture Scale18. As the narratives were interpreted from Karen into English, the investigator took extensive field notes with attention to the principles of narrative. The narratives were recorded word for word as closely as possible as the interpretation was given. Field documentation was subsequently transcribed into a text. Thus, the transcription and documentation of field texts was an in situ construction of the interview.

Study Instrument and Key Variables

The General War Trauma and Torture Scale is a screening tool used to classify torture and war trauma.18 The tool utilized a dichotomous yes/no response to the questions, In your life, have you ever been harmed or threatened by the following: government, police, military or rebel soldiers, or other?; Has any of your family ever been harmed or threatened by the following: government, police, military or rebel soldiers, or other?; and Some people in your situation have experienced torture. Has that ever happened to you? Each question was followed by the prompt, If yes, what was it? This was intended to elicit sufficient information through which the study team could confirm and code the event as primary or secondary torture, or war trauma. Adaptations to the screening instrument were described previously.13 The primary alteration to the instrument in the current study was to include a Likert scale rating of the severity of impact of reported experiences, that ranged from 1- very positive to 5 – very negative.

The study team used widely accepted definitions of war trauma, primary, and secondary torture. War trauma is defined as any occurrence in which human beings, in the context of war, are subjected to conditions of endangerment and extreme trauma – in which individuals directly witness violations to the human welfare of others, or learn about these.25 Primary torture is defined by the United Nations in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) as: “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity…”.26 Secondary torture occurs when acts of torture are inflicted against close contacts or family members of an individual. 27

Analysis: Adapted Narrative Method for Field Texts

Narrative inquiry attends to structure embedded in the ways an individual relates experience. Personal narratives are bound by context, agency, and subjectivity – a narrative inquiry approach preserves this complexity. Through the production of narrative, an individual is able to integrate their unique perspective, agency, and position within the retelling. To work with text-based narratives collected in situ, the research team developed an adapted narrative method for data in the form of field texts. Through the method we examined conceptual features of narrative theory that guided analysis and structured questions of the data.

What is made explicit (or not) within a trauma narrative may represent events that are too difficult to hold in consciousness or those that are tied to a critical component of a healing process. Trauma narratives represent a way through which an individual may choose to communicate the relationships between memory, positional identity, physical and sensory experiences, emotion, and the broader multicultural context of migratory experiences.28,29

Authors contend that narrative retelling represents experience. All experience contains a temporal dimension. Life is experienced in the here and now, but also life is experienced on continuum. The study team examined a fragment of each participants’ narrative, embodied in story that encompassed time and space, and that was reflected upon in relation to the self and experiences of the collective.30 This approach represented an alternative method for capturing narrative data and using a narrative analysis approach.

The study team completed the analysis through the following three steps:

Conducted a content analysis of a subset of 30 narratives (from the broader study sample of 96) to explore prominent themes that emerged within the recounting of experiences. This process served as a way for investigators to examine the credibility of the documentation of knowledge production in this unique context.

Selected and analyzed 11 of the most well-developed narratives shared in response to the Screening Questionnaire through an adapted narrative method. These narratives were characterized as developed because of the length and/or detail that was included. The application of mixed methodologies that authors present in this article is inclusive of the sample of 11 women (Table 1). This process served to contextualize the field text narratives within the larger study.

Refined the analysis to focus on three narratives that most clearly demonstrated the patterns of meaning present, to varying degrees, in all of the narratives. The three exemplars represented major temporal plots and served to reveal points of tension and meaning in the discursive experiences, including where and when participants began their storytelling, key actors within the narratives– parents, teachers, the Burmese Army, and mechanisms through which memories of the trauma narrative were relayed, such as metaphors.

Table 1.

An introduction to the women participants.

| Ler Saw is a Karen woman in her late fifties. She and her husband married in their community of origin when she was eighteen years old. They began having children in Burma, and when the situation became dangerous, fled to a refugee camp in Thailand. The family lived there for the next twenty years. Ler Saw has six living children. Three and a half years ago, Ler Saw and her husband came to the US. Ler Saw discussed multiple long-term health effects, is permanently disabled and unable to work. She experiences debilitating pain, chronic gastrointestinal issues, and depression. She stated that she doesn’t feel healthy. She discussed triggers of memories of the past, feelings of fear that come as a result, and the way and her whole body shakes. Ler Saw stated that she feels much safer in the US, though it’s still hard to forget. |

| Paw Htoo is a Karen woman in her sixties. She spent more than twenty years living in three different camps in Thailand. There she experienced multiple illnesses and an injury that left her with burning pain in her arm, hand and back. Sometimes she gets overwhelmingly dizzy. Paw Htoo was never able to attend school because her family frequently relocated to remain safe in Burma. She has four children and came to the US four years ago. |

| Naw Si is a Karen woman in her mid-forties. She and her family have lived in the US for seven years. She and her husband both work to support their five children. Naw Si discussed health issues she experiences including fevers and a burning leg pain. |

| Bway Paw is a Karen woman in her mid-forties. She and her husband have been married for almost thirty years and have six children. Their family lived in a refugee camp for ten years, and came to the US two and a half years ago. Bway Paw is not able to work because of health problems she experiences, including pain and difficulty with her vision. She discussed ways her physical health impacts her ability to parent effectively. Bway Paw did not attend school. The literacy and English language proficiency her children now have support the family in navigating some of the complexities of life post-resettlement. |

| Leh Mu is a Karen woman in her late forties. She and her family have lived in the US for eight years. Prior to this, the family lived in a refugee camp for eight years. Leh Mu and her husband have been married for twenty-seven years. They have four older children who live at home. Leh Mu works full-time at a food processing facility. |

| Bleh Htoo is a Karen woman in her mid-thirties. She has lived in the US for a year; before that, she lived in a refugee camp in Thailand for eight years. She was married and had her first child when she was seventeen. She now has eight children. She was never able to attend school. In the US she works part time as a home healthcare aide. |

| Eh Hsar is a forty-year-old Karen woman. She has been married for twenty years. Eh Hsar, her husband and their four children lived in a refugee camp for eight years before they resettled to the US ten years ago. Eh Hsar discussed her difficult experiences in the past, and resulting thinking too much and problems with my heart. She indicated that she has been referred to a therapist, but prefers not to meet with anyone. Eh Hsar works as a patient care assistant (PCA) for a family member. |

| Gay Lah is a Karen woman in her late forties. She lives with her husband of twenty-seven years and three sons. They resettled to the US eight years ago, and before that lived in a refugee camp in Thailand for almost twenty years. Gay Lah was never able to attend school, she generates income for her family as a weaver. |

| Mu Aye is a Karen woman in her late forties. She was married when she was seventeen, and now has eight children. Mu Aye lived in a refugee camp with her husband and children for more than twenty years. They have lived in the US for four years. Mu Aye experiences severe depression and other health problems, and reported that she is permanently disabled and unable to work. She has pain, headaches and trouble sleeping. Mu Aye shared detailed experiences from the war that she and her husband survived. She reflected on her children’s experiences as they fled from the Burmese Army. |

| Thaw Day is a Karen woman in her mid-fifties. She lived in a refugee camp for more than twenty years, and came to the US four years ago. She has been married for twenty-six years, and has six children who all live with her. Thaw Day was able to attend some school as a child, but this was interrupted because her family had to continually relocate to safer areas in Burma. She works in a bakery. |

| Mui Paw is a Karen woman in her late thirties. She and her family lived in a refugee camp for ten years, and have now lived in the US for eleven years. She has four children and has been married for nineteen years. Mui Paw is not able to work because of a disability. She experiences chronic generalized pain. She states that she is currently seeing a health provider to help her with difficult memories from her experiences in the past. |

All names are pseudonyms. Demographic information has been altered to preserve anonymity.

Through this approach, the authors examined the ways in which physical and sensory experiences framed the trauma narratives participants reconstructed in the research setting. Women’s narratives were conveyed contextually and interactively, and not predicted prior to fieldwork nor through predetermined instrumentation.

Findings

Our aim in analyzing the data using an adapted narrative inquiry for field texts was to identify the authentic voice within the narratives.30 Critical engagement with the concept of borders was relevant to the analysis and interpretation of trauma narratives. Although the analysis was not focused explicitly on establishing the role of identity within a woman’s trauma narrative, authors acknowledged the relevance and importance of identity and its relationship to the questions explored within the data.31 The study team analyzed the data through two perspectives in narrative methodology, the function of the narrative (Tables 2 and 3) and the holistic orientation of the narrative (Table 4).30 Given the nature of interpreted data, we did not focus on the structural linguistic formation of the text.

Table 2.

Analysis of function: Nuances of severity and response characterization among sample of 11 participants.

| Participant | Torture Classification | Perceived Severity* | Reference to Severity | Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| 14 | Primary torture | Very negative | Sometimes they come and burn the house or village down. | Out of your control/Acts of violence |

| 54 | War Trauma | Very negative | You’re hiding in the jungle. If they catch you they will kill you. [Or] They would take people half way, then leave them and tell them to walk back on their own. But people didn’t know the way. | Out of your control/Acts of violence |

| Surrender | ||||

| 16 | Primary torture | Very negative | If you kill me, it would be better for everybody. | Surrender |

| 76 | Primary torture | Very negative | People can’t go back and do things anymore. They Burmese Army is still there. | Surrender |

| 21 | War trauma | Very negative | The Burmese Army is trying to kill you while your dad is doing that. | Surrender |

| Ordering | ||||

| 32 | Primary torture | Very negative | The worst experience anyone could have. You don’t sleep well, you don’t eat well. You have nowhere to stay. | Sorting/ranking |

| 35 | Primary torture | Very negative | I can’t even explain how scary that was. I was in fear. Running with them. You don’t have food. You’re starving out there. | Sorting/ranking |

| 69 | Primary torture | Very negative | It was the worst experience. I was starving. | Sorting/ranking |

| Defined by choices | ||||

| 44 | Secondary torture | Very negative | It was a really terrible experience. Moving to Thailand helped a little bit. Moving to America made it easier. You have to pay bills but you don’t worry about them coming to kill you. | Tradeoff/Hard choices |

| 52 | War Trauma | Very negative | I remember running away, hiding. If people say they are coming and we have time, then we run away. If we don’t have time, we stay. | Tradeoff/Hard choices |

| Separate from consciousness | ||||

| 80 | Primary torture | Very negative | With my dad, it is really hard to talk about. | Avoidance |

Perceived severity was measured with a 5-pt Likert type response scale ranging from 1 (very positive) to 5 (very negative).

Table 3.

Frequencies of physical and mental health symptoms and diagnoses reported among sample of 11 participants.

| 81.8% clinically significant mental distress |

| 54.5% chronic pain |

| 54.4% general physical health concerns |

| 36.4% high blood pressure |

| 27.3% headaches |

Table 4.

Narrative inquiry analysis orientation framework. Adapted from 30. Clandinin DJ, Connelly FM. Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000.

| Term | Interaction | Continuity | Situation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Personal | Social | Past | Present | Future | Place | Action |

| Applied | ACTOR – unique characteristics, e.g. perceived severity of experience, people or groups | TEMPORALITY – at what point in time did the individual begin her narrative and what were patterns of remembering across time | THE BODY – in what ways did the individual describe physical and sensory experiences of trauma | ||||

| Category | Being a mother | Remembering childhood | Embodied trauma | ||||

| Exemplar | I was born in the jungle. My son was born in the jungle. | Back in Burma, my dad threatened me. He is passed away now. I was useless. I was only 12. We had to run away from the Burmese Army to find food. He said I’m going to drown you, kill you. The BA is trying to kill you, and your dad is doing that. | With me my heart is aching if I hear really loud noises. My heart feels like I have to run away. If my neighbor is really loud, I don’t feel safe. I want to use the bathroom. I can’t sit still. Memory comes back in my body. | ||||

Function: Integrating quantitative findings with qualitative narratives

Authors considered the function of the narrative as women recontextualized their remembered experiences within a discussion of the ongoing impact of those experiences. One way that authors explored function was through an assessment of self-perceived severity of torture and war trauma experiences through a structured 5-item Likert scale included after each question on the Torture and War Trauma Screening Questionnaire. This question frequently compelled further qualitative remembering and retelling of women’s experiences in war. The further retelling served to clarify the nuances of women’s experiences at the upper extreme of the scale. The study team observed that a 5-item severity rating scale imposed a ceiling, limiting both the teller’s capacity to express and the recipient’s capacity to understand. By applying a case-oriented merged analytic approach in mixing the data, where authors identified cases representing patterns in the data, the study team identified that ratings at the upper extreme of the scale held discrete categories of meaning in terms of how women experienced trauma.32,33

Authors identified five categories of meaning that reflected variations in ways that women reported experiencing severe distress in response to reported torture and war trauma experiences. Women reflected on acts of violence that were beyond their control, resulting in the loss of home or security. Several participants described a sense of surrender to their circumstances. The surrender was described in both individual and collective contexts. Women participants periodically used language that implied a ranking or an ordering of experiences, the worst, or, I can’t even explain. Related to this was a category of avoidance. Authors distinguished this from ordering because of the potential unique resulting health consequences. Avoidance was characterized by responses that suggested a participant avoided or suppressed thoughts related to events experienced in the war. Finally, women reflected on the choices they were forced to make as a result of their experiences. The outcomes of these choices may have increased or decreased levels of severity that women associated with an isolated event.

The second objective for integrating qualitative and quantitative data was to identify common patterns that existed in concurrent strands of data collection. Authors identified 100.0% of the women had reported directly experiencing threats from the government and had perceived these experiences as strongly or very strongly impacting their wellbeing. Additionally, 63.6% of the women shared that family members had received threats from the government and these experiences, while indirect, were also perceived as having a strong detrimental impact on their wellbeing.

Among the sample of 11 women, 63.6% (7 of 11) reported personal experiences of torture and 9.1% (1 of 11) reported family members had been tortured. The collective impact of torture used by the government against the Karen and similar ethnic minorities in Burma were understood among the women as negatively impacting their wellbeing. In the literature, torture is often associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes.34 As such, authors found it imperative to explore the potential related physical and mental health problems among the sample of 11 women. Several important physical and mental health problems were endorsed among the women (Table 3). The prevalence of physical health problems converged with the degree to which participants in the larger study reflected on physical and sensory experiences as they discussed their experiences in war.

Orientation: Language and meaning

Next, the study team considered the specific language and meaning conveyed through three of the narratives (Table 4). Authors explored the orientation of participant narratives by assigning meaning to interactions that were present in the data. Specifically, the study team focused on interactions that represented social or personal relationships; continuity - a construct relevant to the timing or emergence of the narrative; situation – at what point in time the narrative was situated; and what actions or sensations were elicited through the retelling. The study team applied these constructs through an innovative examination of actors, temporality, and the physical body relevant to text in the form of field notes. Table 4 relates concepts relevant to narrative to the structure of the field texts.

The study team structured the report of findings by three major themes. Each theme is presented through the brief participant narrative that best elucidated the theme. Authors interpreted the narrative in the context of this theme, and subsequently consider meaning across the broader experiences expressed by the sample of 11 women.

Narrative Theme 1: Remembering Childhood

What happened in Burma, I carry it with me, it’s still here. (laughs) Back in Burma, my dad threatened me. He is passed away now. I was useless. I was only 12. We had to run away from the Burmese Army to find food. We didn’t have any food. He said I’m going to drown you, kill you. That was the worst experience. The Burmese Army is trying to kill you. And your dad is doing that (20211021).

Women engaged deeply cultural accounts of childhood to contextualize a broader trauma narrative. This participant elected to begin recounting her narrative with a description of an experience that occurred during childhood. The story withstood the passage of time in that it remained a defining memory of coming of age in war. The participant opened her narrative orienting us to the passage of time, beginning with a memory from childhood that has remained with her, through her older adult years. The use of the term carry suggested a physical task involved in maintaining the presence of the narrative across time. The orientation of actors in this excerpt is striking, how in the midst of fleeing war and experiencing hunger she chose to reflect on a moment that represented a specific interaction during which her father threatens her as a 12-year old child. A brief, knowing and sarcastic laugh noted in the field notes punctuated how she situated this moment within her narrative. In her retelling, she referenced the interaction she shared as being the worst. It suggested that it was not simply the war, but the interaction with her father within and despite of the war, that was the worst. The narrative functioned as an expansion of the notion of conflict and gives voice to the struggle of families who navigate a way forward under extremely stressful circumstances.

Expressions made by the broader group of 11 women that suggested remembering childhood, regardless of the point at which the individual or family fled Burma, and length of time beyond childhood that women experienced war, was important. Actors were positioned by women in varying ways. One woman recalled a physical encounter that she had with a soldier, They [the Burmese Army] came up to me and they touched my chin. And that’s all I remember. I was 4 (20521052). Another woman reflected on a tragedy she witnessed as a 15-year old girl, and how her teacher, who was the victim of the tragedy, continued to try to help her. She recalled, I was 15 or 16, I had to walk to school in the city. A teacher was going to send us to school. She stepped on a landmine….She lost both legs. It was bloody and scary. It was just two of us kids. We were so scared. I don’t know how to explain the fear. She [the teacher] told us not to come close by in case there were more landmines. We hid (20141014). These brief allowances into the memories of war and trauma underscored questions authors asked of the data, such as how and why these specific moments in time were shared as representations of the war in the research encounter?

Narrative Theme 2: Being a Mother

I was born in the jungle. My son was born in the jungle. I was pregnant and running. You want to start a campfire but you don’t want the enemy to find you. I had 5 children in Burma.

The way they [the Burmese Army] come and shout down. It’s hard to carry your kids. And move with your kids. I can’t even think about those experiences.

My husband had to run away from the Burmese Army. He had to take care of his family and the Burmese Army was trying to kill him. He was a teacher. Students from the Karen military were his class. People [the Karen military] let them go to school and be in the military. The Burmese Arm targeted him, they [the Karen military] had to send him somewhere else for his safety. They [the Karen military] had to send us [participant and her children] somewhere too. We were scared to be close to each other. People sent us to little houses/camps in the area because I had little children. The Karen military took us to safety.

It’s hard when you have 5 children and have to run. I was born in the jungle and one of my children was born in the jungle…(20441044).

Mothering in war is foundational to the notion of the gendered nature of conflict, and germane to the ways in which participants oriented themselves in their experiences. Authors noted ways in which women relied on their physical body to frame retelling experiences as maternal caregivers. The narrative authors selected and analyzed as an exemplar of the notion of mothering in war began and ended with a metaphor describing a connection the women felt between herself and her son. The account functioned to tie the woman’s narrative of the past to her future, and implied that she would consistently and repeatedly return to her connection to her son, as a mother, when she reflected on her experiences in Burma. The narrative oriented the listener to the experience of mothering in war in two ways. First, through the notion of caring for and physically carrying children in conflict. This passage particularly highlighted the experience of moving with children - How to feed children and keep them protected from the elements as they were hiding in the jungle? How to move with children and keep them quiet so as not to be discovered? And how to keep children healthy in the absence of access to health care and as these women dealt with and experienced their own traumas? These experiences were echoed in the narratives of the group of women. Participants recounted these memories as though they were still asking themselves these questions. The reference to the jungle was stated literally, women remembered moments they spent in the jungle caring for their children. The reference also functioned as a metaphor for living in the midst of conflict. The jungle was where people hid as they fled.

Second, the narrative oriented the listener to the implied responsibilities of women in families, emphasizing the gendered experiences of war referenced above. When families were separated, women reported that they were more likely to remain with their children. There were implications in this role for the shared narratives of migration between mothers and their children.

In the full sample of narratives, maternal physical and sensory experiences of trauma and survival shaped how women described experiencing fear. One participant said of her 22-year-old son, he knows more than the others. I was pregnant with him during war. I wonder if what I experienced, he experienced because I was pregnant (20301030). Another woman described how mothers and their children experienced the relationship between fear and physical difficulties jointly, my oldest son has a lot of trauma, he lived through war as a child. He was aware, he knew what was going on. A huge missile came down on our town. There was a huge explosion. Me and my son were in a hole, he was 8. He was so scared. When we would get water from the river, the Burmese Army would scare him. I get sick easily. It was hard to take care of him (20141014). Women described physical experiences in ways that established tangible connections between a mother and child living through war. These experiences conveyed attachment, contextualized within trauma, and thus resulted in outcomes that women described as both powerful and harmful within families.

The decisions that women made in terms of prioritization and keeping families safe, versus together, highlighted the shift in dynamics that families navigated through war. Women reflected on the weight and responsibilities of mothering in war, including keeping her children alive in the jungle. Spouses became prominent within these reflections, coming to Thailand was hard. I wasn’t able to walk. My husband was carrying supplies and my child. I thought, if you kill me, it would be better for everyone. I wasn’t able to move. I was in between life and death. I didn’t know if I would live or die (20161016).

Narrative Theme 3: Embodiment of Trauma.

With me my heart is aching if I hear really loud noises. My heart feels like I have to run away. If my neighbor is really loud, I don’t feel safe. I want to use the bathroom. I can’t sit still.

Memory comes back in my body. I feel like I have to use the bathroom.

I did have to try to find money. I washed dishes. I would go work for people. People locked me in their room. They don’t want us to leave. They would put us in a room to sleep in, but lock us up. I don’t feel comfortable in a locked room. I am claustrophobic. Even going to the bathroom, or in the car. I feel like someone is going to lock me in. My breathing gets shallow (20801080).

Trauma can be felt, stored, and expressed in the body.28 This participant oriented the listener to the ways she experienced emotion through her physical body (i.e. her heart, her breath, the urge to use the bathroom). She described how physical and sensory ways of being became part of her narrative of war. In her statements, however, she did not indicate how she responded or whether she acted on the physical and sensory experiences that shaped the ongoing memories of her experiences in war. The narrative functioned as an example of the ways that expressions and memories of trauma can be held and experienced prominently through physical and sensory experiences. And that these physical and sensory experiences exist both within and parallel to processing those same experiences cognitively.

The narrative highlighted a broader pattern present among the full sample, where women retold the experiences in war through physical responses to traumatic events. For example, women recounted various and immediate external responses, including descriptions of hiding or fleeing such as, When the Burmese army came, we all tried to go to a hole. I went in the hole, but she didn’t make it in time (20621062) or, they tell you to give an answer and I couldn’t talk anymore (20141014). In other situations, women described physical responses internalized, such as freeze – a state of self-paralysis or becoming physically numb, two of my children died. I felt lonely, not like myself anymore. I felt unconscious (20161016). Or to be startled, described as an enhanced state of sensory sensitivity accompanied by an exaggerated intensity of physiological response to threatening stimuli. In the larger collection of 11 narratives, women described how they interpreted and understood sensory knowledge, including perceptions informed by means of tactile, aural, and visual sensory experiences. For example, one woman related the past to experiences she has now. She shared, when I hear a dog bark, in my heart I feel something is wrong. My heart feels cold, I feel like something is about to happen. It is beating fast and hard to make stable (20141014). Interviews with women revealed glimpses into sensorial experiences in relationship to the larger narratives of migration.

Discussion

Central to the inquiry, the study team considered ways of knowing and retelling produced by Karen women with refugee status who survived war and are now living in the United States post-resettlement. Employing an adapted narrative method relevant to data in the form of field texts facilitated an interpretation of the ways in which knowledge was produced by women through a description of the core narrative, the individual trauma narrative, and its consistent expression through physical and sensory terms. The intent in using features of narrative inquiry was to ground the analysis in the voices of women and interpret what was understood to be the intended meaning and context of our interactions with women participants as they claimed their experiences of war trauma and torture and recontextualized their histories to the present. Among the questions asked of the narratives shared by women through the course of the study were: Where and when did women begin their stories? To what extent did they disclose experiences of war trauma and torture? And how did women position a narrative of the self within a collective narrative?

Within their narratives, women described lived experiences, acquired through or defined by tactile, aural, visual, and physical encounters. Deeply cultural accounts revealed ways emotions were felt in Karen women participants’ physical bodies. Emotional states were described through the physical body. These felt states included impact on the heart, thinking too much, and various other ways fear was embodied. Women described responding physically to traumatic experiences through hiding in a hole, fleeing, freezing, or feeling startled. The physical consequences of limited resources were described including, hunger and unmet health needs. Various types of threats to the physical body were prominent in the remembering and retellings. Women’s narratives provided physical and sensorial interpretations of their torture and war trauma experiences, disclosing what was meaningful for an individual in that recalled moment and how those sensations have evolved through time and place.

The timing of and the actors present within the narratives emerged as important structural constructs and borders in the stories of women. Women chose to begin their narratives at different points in their lives. The impact of experiences, though, were consistently described as enduring to their present, post-resettlement life, regardless of the point at which a woman began her story. Women connected the past with the present as they reasoned through past physical and sensory experiences as current triggers with negative and recurrent impacts on their physical, cognitive, and emotional health. Women remembered physical experiences that occurred during childhood that were important to them still in the present. They retold their experiences at points in their lives as mothers, and ways that the physical body was integral to the ability to mother and care for children in war.

In terms of actors present within the narratives, the strong presence of the Burmese Army and to a lesser extent, the Karen Army, was expected given the nature of the interviews. What uniquely defined each narrative was the way the participant constructed her positionality in relation to other actors that she introduced - to her children, childhood or adult friends, teachers, family members, mothers, and fathers within the memories she chose to share. Only in rare circumstances did a woman describe circumstances in war associated with positive impacts on interpersonal relationships.

The narrative embodies a self-constructed border and is a way through which an individual can integrate the cultural context and difficult life events they experienced. Narratives served as ways through which individuals communicate the interrelationships among physical symptoms and the psychological, social, or cultural context of these symptoms.28 Traumatic events may be processed as narratives when they are a too difficult to hold in consciousness. Young (2018) suggested that the space between created borders becomes the family; thus the articulation of narrative is a critical component of a healing process.23 Documentation of treatment approaches with patients with somatic symptoms show that emphasizing narratives that link trauma, culture, and physical symptoms are useful. Transforming stress into words may alleviate emotional distress and decrease the physiologic stress response.35

The ways in which war-affected individuals express thought and emotion may signify how physical symptoms relate to past trauma. It is essential that health providers consider situational stressors, cultural aspects of mourning and symptomatology, and existing coping strategies in developing interventions that are grounded in personal narratives.36 However, refugees may not be asked about a history of torture when they seek healthcare in the United States.37

The primary limitations in the analysis are related to the assumption that the brief field narratives, lasting on average 10–40 minutes, reflected a more sustained sense of participants’ past and ongoing experiences. The study team did not anticipate the extent of qualitative data that would emerge, and therefore did not anticipate a need to record this portion of the interaction with participants. As rich qualitative descriptions emerged, the study team determined that introducing a recorded portion of the encounter would shift the dynamics of the interactions, potentially impacting the organic discussions surrounding experiences. Therefore, data were extracted from extensive field texts. All of the interactions with participants occurred through the use of an interpreter. It is likely that through language interpretation, meaning was shifted.

Participants constructed knowledge in the remembering and retelling of their individual trauma narratives. The study team interpreted the texts through a defined positionality and with the recognition that participants represented a population that experiences barriers to being seen and heard. Thus, the approach to the data centered around a responsibility to amplify those voices, but not appropriate them. Next steps will include an examination of the ways through which maternal caregivers communicated distress through physical connections with their children, and associations between exposure to torture and other forms of war trauma, physical health, and youth adjustment.

Conclusion

The global prevalence of forced displacement is at its highest point in recorded history. Participants in the sample explored and developed brief trauma narrative borders around memories and experiences that had persisted through time and into post-resettlement spaces. The connection between trauma and the physical body suggested that understanding physical health outcomes in forced displacement and migration is as germane to holistic treatment of trauma. Recognizing these connections will inform responses to health in war-affected communities. Critical engagement with physical narratives expands this awareness.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the essential contributions in early project phases by the Center for Victims of Torture, headquartered in St. Paul, Minnesota. Specifically, we thank the Director of Research, Craig Higson Smith for his guidance and expertise. We thank the Karen Organization of Minnesota for essential project and recruitment support. We attribute the depth and richness of the data, in part, to our interpreter, Ehtaguy Zar. We thank Dr. Abigail Gewirtz for her guidance and mentorship.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K12HD055887. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Sarah J. Hoffman, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Maria M. Vukovich, University of Denver.

Cynthia Peden-McAlpine, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Cheryl L. Robertson, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Kristin Wilk, University of Minnesota School of Nursing.

Grey Wiebe, University of Minnesota School of Nursing

Joseph E. Gaugler, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

References

- 1.Shishehgar S, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Green A, Davidson PM. Health and socio-cultural experiences of refugee women: an integrative review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;19(4):959–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidebotham E, Moffatt J, Jones K. Sexual violence in conflict: a global epidemic. The Obstet Gynaecol 2016;18(4),247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson JE, Brown C, Russell EB, Khamphakdy-Brown S. Acculturation, partner violence, and psychological distress in refugee women from Somalia. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(11), 1654–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deacon Z, Sullivan C. Responding to the complex and gendered needs of refugee women. Affilia. 2009;24(3),272–284. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baird MB. Well-being in refugee women experiencing cultural transition. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2012;35(3),249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto-Govindasamy LS, Rose V. An ethnographic process evaluation of a community support program with Sudanese refugee women in western Sydney. Health Promot J Austr. 2011;22(2),107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miszkurka M, Goulet L, Zunzunegui MV. Contributions of immigration to depressive symptoms among pregnant women in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(5),358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavlish C Action responses of Congolese refugee women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37(1),10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNHCR. (1951). The refugee convention 1951. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/4ca34be29.pdf

- 10.Batalova J Spotlight on refugees and asylees in the United States. Migration Information Source. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNHCR. (2018). Resettlement data finder. Retrieved from https://www.rsq.unhcr.org/en/#GNt9

- 12.Devictor X (2019). 2019 update: How long do refugees stay in exile? To find out, beware of averages. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/dev4peace/2019-update-how-long-dorefugees-stay-exile-find-outbeware-averages

- 13.Hoffman SJ, Vukovich MM, Gewirtz AH, Fulkerson JA, Robertson CL, Gaugler JE. Mechanisms explaining the relationship between maternal torture exposure and youth adjustment in resettled refugees: a pilot examination of generational trauma through moderated mediation. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2020December;22(6):1232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman SJ, Shannon PJ, Horn TL, Letts J, Mathiason MA. Health of war-affected Karen adults 5 years post-resettlement. Family Practice. 2021January22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf

- 16.IHRC. (2014). Legal memorandum: War crimes and crimes against humanity in Eastern Myanmar. Retrieved from: http://hrp.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014.11.05-IHRC-Legal-Memorandum.pdf

- 17.Schweitzer RD, Brough M, Vromans L, Asic-Kobe M. Mental health of newly arrived Burmese refugees in Australia: contributions of pre-migration and post-migration experience. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry.2011April;45(4):299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shannon PJ, Vinson GA, Wieling E, Cook T, Letts J. Torture, war trauma, and mental health symptoms of newly arrived Karen refugees. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2015November2;20(6):577–90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.British Broadcasting Corporation. Myanmar coup: Aung San Suu Kyi detained as military seizes control. Retrived from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55882489

- 20.Bamberg M, Georgakopoulou,A. Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. Text & Talk. 2008;28(3),377–396. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anzaldúa G Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Spinsters/Aunt Lute. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Risch BA. Fostering feminist civic engagement through Borderlands theories. Feminist Teacher. 2012;22(3),197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young SS, Muruthi BA, Chou JL, Chevalier M. Feminist Brderland theory and Karen refugees: finding place in the family. J Fem Fam Ther. 2018;30(3),155–169. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman SJ, Tierney JD, Robertson CL. Counter-narratives of coping and becoming: Karen refugee women’s inside/outside figured worlds. Gender, Place & Culture. 2017September2;24(9):1346–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 26.United Nations General Assembly. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. 1984. https://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/39/a39r046.htm

- 27.Office of Refugee Resettlement, Administration for Children and Families, & United States Department of Health and Human Services (2010). Torture survivors program (TSP) eligibility determination guidance. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/eligibility_guidelines_orr_2010_1.pdf

- 28.Waitzkin H, Magana H. The black box in somatization: unexplained physical symptoms, culture, and narratives of trauma. Social Science & Medicine. 1997September1;45(6):811–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31(6),539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clandinin DJ, Connelly FM. Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bamberg M Who am I? Narration and its contribution to self and identity. Theory Psychol. 2011;21(1),3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell LL, Peterson CM, Rud SR, Jutkowitz E, Sarkinen A, Trost S, Porta CM, Finlay JM, Gaugler JE. “It’s like a cyber-security blanket”: the utility of remote activity monitoring in family dementia care. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(1),86–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Kolk BA. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alemi Q, James S, Montgomery S. Contextualizing Afghan refugee views of depression through narratives of trauma, resettlement stress, and coping. Transcultural psychiatry. 2016October;53(5):630–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Briere JN, Scott C. Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (DSM-5 update). Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks: CA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shannon PJ. Refugees’ advice to physicians: how to ask about mental health. Family Practice. 2014August1;31(4):462–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]