Abstract

Background

N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), classified as a probable human carcinogen, has been found as a contaminant in the antihypertensive drug valsartan. Potentially carcinogenic effects associated with the consumption of NDMA-contaminated valsartan have not yet been analyzed in large-scale cohort studies. We therefore carried out the study reported here to explore the association between NDMA-contaminated valsartan and the risk of cancer.

Methods

This cohort study was based on longitudinal routine data obtained from a large German statutory health insurance provider serving approximately 25 million insurees. The cohort comprised patients who had filled a prescription for valsartan in the period 2012–2017. The endpoint was an incident diagnosis of cancer. Hazard ratios (HR) for cancer in general and for certain specific types of cancer were calculated by means of Cox regression models with time-dependent variables and adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

A total of 780 871 persons who had filled a prescription for valsartan between 2012 and 2017 were included in the study. There was no association between exposure to NDMA-contaminated valsartan and the overall risk of cancer. A statistically significant association was found, however, between exposure to NDMA-contaminated valsartan and hepatic cancer (adjusted HR 1.16; 95% confidence interval [1.03; 1.31]).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the consumption of NDMA-contaminated valsartan is associated with a slightly increased risk of hepatic cancer; no association was found with the risk of cancer overall. Close observation of the potential long-term effects of NDMA-contaminated valsartan seems advisable.

The angiotensin II receptor antagonist valsartan is used predominantly to treat hypertension and heart failure (1– 4). In 2018, N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) was detected in the valsartan active substance manufactured by Zhejiang Pharmaceuticals (5, 6). Preparations containing the contaminated valsartan were withdrawn from the market by regulatory agencies across the world (5, 7). In Germany, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) ordered the recall of drug products contaminated with NDMA in July 2018. The NDMA contamination seems to be the result of a change in the manufacturing process in 2012 (8). Thus, patients may have been exposed to contaminated valsartan from 2012 until the recall. Investigations of other sartans with a tetrazole ring structure have revealed contamination with no more than small amounts of NDMA in only a few cases. NDMA is one of the most potent mutagenic carcinogens in animal models and was classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as probably carcinogenic to humans (9– 11).

A Danish cohort study based on healthcare system registry data reported no statistically significantly elevated overall risk of cancer and no increase in the risk of some individual cancers after exposure to drug products containing NDMA-contaminated valsartan (12). However, the sample size of the Danish study was limited to a total of 5150 patients, which may explain the non-significance of the results (12). For our cohort study we used a large longitudinal sample from the AOK, a large German statutory health insurance fund. We examined the association between filled prescriptions of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug product prescription and cancer risk in comparison with non-contaminated valsartan. Our results provide insights based on a substantially higher number of patients than in the Danish study. We also focus on various cancer outcomes with a large number of cancer events.

Methods

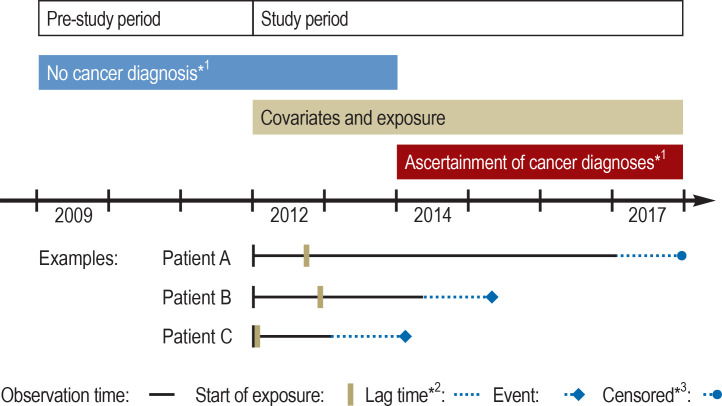

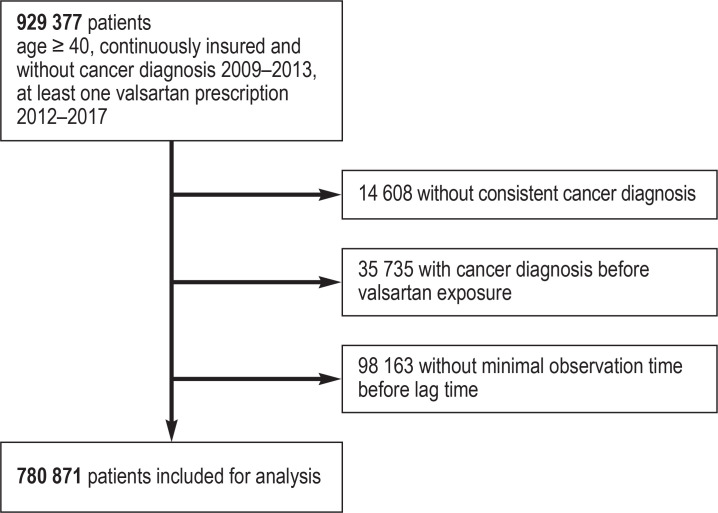

The Figure provides an overview of the study design. The data set comprises health insurance data from the AOK. It includes all patients aged 40 years or older at the beginning of 2012 who filled at least one prescription of valsartan between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2017. Potential NDMA contamination was assessed on the basis of the pharmaceutical registration number (PZN) as product identifier in the filled prescription records and information on valsartan drug products from marketing authorization holders. The outcome was an incident cancer diagnosis. Cox regression models with time-varying variables and adjustment for potential influencing factors were used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) for cancer overall and for several individual cancer types. Detailed information can be found in the eMethods.

Figure.

Overview of the study design

*1 For the evaluation of long-term use (3 years) the absence of cancer until the end of 2014 was required; follow-up started at the beginning of 2015.

*2 Depicted is the lag time of the main analysis (lag time of 1 year); for the evaluation of long-term use (3 years), no lag time was included.

*3 Data censored because of death, end of insurance cover, or end of study.

Results

The study cohort comprised 780 871 persons with a filled valsartan prescription during the period 2012–2017. Of these, 409 183 were classified as ever and 371 688 as never exposed to potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan. The characteristics of the study cohort in 2012 are presented in Table 1. The mean and median person-times were 3.1 years (standard deviation 1.5 years) and 3.25 years (interquartile range 2–4.75), respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort.

| NDMA exposure | ||||

| Characteristic |

All

(N = 780 871) (%) |

Not exposed

(n = 371 688) (%) |

Exposed

(n = 409 183) (%) |

|

| Gender | Male | 312 146 (40.0) | 156 360 (42.1) | 155 786 (38.1) |

| Female | 468 725 (60.0) | 215 328 (57.9) | 253 397 (61.9) | |

| Age: median (IQR) | 68 (57–75) | 66 (55–74) | 69 (58–76) | |

| Prevalent use | No | 534 519 (68.5) | 300 370 (80.8) | 234 149 (57.2) |

| Yes | 246 352 (31.5) | 71 318 (19.2) | 175 034 (42.8) | |

| SSRI | 36 825 (4.7) | 16 202 (4.4) | 20 623 (5.0) | |

| NSAID | 316 350 (40.5) | 150 730 (40.6) | 165 620 (40.5) | |

| 5α-Reductase inhibitors | 6136 (0.8) | 2684 (0.7) | 3452 (0.8) | |

| Low-dose ASA | 94 061 (12.0) | 38 988 (10.5) | 55 073 (13.5) | |

| Statins | 237 998 (30.5) | 102 502 (27.6) | 135 496 (33.1) | |

| Spironolactone | 25 235 (3.2) | 9986 (2.7) | 15 249 (3.7) | |

| Glucocorticoids | 72 493 (9.3) | 32 805 (8.8) | 39 688 (9.7) | |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 19 219 (2.5) | 9025 (2.4) | 10 194 (2.5) | |

| Polypharmacy | 456 508 (58.5) | 197 710 (53.2) | 258 798 (63.2) | |

| Diabetes | 277 266 (35.5) | 125 388 (33.7) | 151 878 (37.1) | |

| COPD | 103 474 (13.3) | 45 356 (12.2) | 58 118 (14.2) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 136 566 (17.5) | 55 554 (14.9) | 81 012 (19.8) | |

| Alcohol-related disease | 13 512 (1.7) | 6665 (1.8) | 6847 (1.7) | |

| CCI | Low (0) | 227 331 (29.1) | 121 183 (32.6) | 106 148 (25.9) |

| Medium (1–2) | 333 351 (42.7) | 158 327 (42.6) | 175 024 (42.8) | |

| High (≥ 3) | 220 189 (28.2) | 92 178 (24.8) | 128 011 (31.3) | |

ASA, Acetylsalicylic acid; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; COPD, chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease;

IQR, interquartile range; NDMA, N-nitrosodimethylamine; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

For the outcome cancer overall, exposure to potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan was not associated with an increased risk of an incident cancer diagnosis in comparison with exposure to non-contaminated valsartan (adjusted HR 1.00, 95% confidence interval [0.98; 1.02]; eTable 1). A similar result was obtained after adjustment for age and gender only (HR 1.01 [0.99; 1.03]). Based on the manufacturers’ information about the packages of valsartan drug products sold, we were able to classify the filled valsartan prescriptions into different degrees of likelihood of contamination, from possibly to probably contaminated with NDMA (eMethods). Exposure to neither possibly (adjusted HR 1.00 [0.97; 1.03]; eTable 1) nor probably (adjusted HR 0.99 [0.97; 1.02]; eTable 1) NDMA-contaminated valsartan was associated with the endpoint cancer overall. Differentiation between prevalent and incident exposure to potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan showed no association with the endpoint cancer overall in either case (adjusted HR 0.97 [0.94; 1.01] and adjusted HR 1.01 [0.98 to 1.04], respectively; eTable 1). Higher exposure to potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan, based on defined daily doses (DDDs), had no effect on the overall cancer rate (etable 1). For sensitivity analyses, the lag time between the last quarter assessed for exposure status and the initial cancer diagnosis or the end of the person-time was varied from 6 months to 2 years. We observed no significant differences across this lag time spectrum (etable 2). In a separate analysis we examined long-term use of valsartan, defined as filling of valsartan prescriptions in at least nine quarters of the first 3 years of the study period. Long-term use showed no association with the change in overall cancer rate (adjusted HR 0.96 [0.89; 1.04]); neither were dose-dependent effects observed (etable 1).

eTable 1. Overall cancer risk from use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug products compared with uncontaminated valsartan.

| Hazard ratio [95% CI]*1 | Sample size/ cancer cases | |

| Exposure to NDMA-contaminated valsartan | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 371 688/17 504 |

| Exposure | 1.00 [0.98; 1.02] | 409 183/24 752 |

| Exposure in dose categories | ||

| 0 to ≤ 90 DDDs | 1.00 [0.97; 1.03] | 130 684/8449 |

| > 90 to ≤ 170 DDDs | 1.01 [0.99; 1.04] | 144 876/8390 |

| > 170 DDDs | 0.98 [0.95; 1.00] | 133 623/7913 |

| NDMA exposure | ||

| Possible NDMA exposure (contaminated valsartan batches <75%) | 1.00 [0.97; 1.03] | 111 962/7761 |

| Probable NDMA exposure (contaminated valsartan batches >=75%) | 0.99 [0.97; 1.02] | 297 221/16 991 |

| Only prevalent valsartan use*2 | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 71 318/5754 |

| Exposure | 0.97 [0.94; 1.01] | 175 034/12 464 |

| Only incident valsartan use*2 | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 300 370/11 750 |

| Exposure | 1.01 [0.98; 1.04] | 234 149/12 288 |

| Long-term valsartan use*3 | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 64 836/3472 |

| Exposure | 0.96 [0.89; 1.04] | 14 686/817 |

| Exposure in dose categories | ||

| 0 to ≤ 90 DDDs | 1.00 [0.86; 1.17] | 2629/166 |

| > 90 to ≤ 170 DDDs | 1.03 [0.89; 1.18] | 3777/220 |

| > 170 DDDs | 0.91 [0.83; 1.01] | 8280/431 |

| Incidence rate*4 per 100 000 persons | ||

| No exposure | 1254.71 | |

| Exposure | 1270.30 | |

*1 Lag time 1 year, fully adjusted for sex; age; polypharmacy (defined as prescription of five or more different drugs); prescription of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), non-ASA non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 5α-reductase inhibitors, statins, spironolactone, glucocorticoids for systemic use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy; the comorbidities diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and alcohol-related diseases; the Charlson comorbidity index (score); and prevalent valsartan use

*2 Without covariate “prevalent valsartan use”

*3 Long-term valsartan use is defined as valsartan prescription in at least nine quarters within the first 3 years of the study period.

*4 Standardized to the German population over 40 years in 2011 (e2)

DDD, defined daily dose; NDMA, N-nitrosodimethylamine; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

eTable 2. Overall cancer risk and liver cancer risk from use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug products compared with uncontaminated valsartan, different lag times.

| Hazard ratio [95% CI]* | Sample size/cancer cases | |

| Cancer overall: valsartan prescription | ||

| Lag time 6 months | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 386 322/19 383 |

| Exposure | 1.00 [0.99; 1.02] | 443 442/26 375 |

| Lag time 12 months (main analysis) | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 371 688/17 504 |

| Exposure | 1.00 [0.98; 1.02] | 409 183/24 752 |

| Lag time 24 months | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 291 955/11 252 |

| Exposure | 0.99 [0.97; 1.01] | 371 555/16 966 |

| Liver cancer: valsartan prescription | ||

| Lag time 6 months | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 367 705/485 |

| Exposure | 1.16 [1.04; 1.31] | 418 219/774 |

| Lag time 12 months (main analysis) | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 354 628/444 |

| Exposure | 1.16 [1.03; 1.31] | 385 167/736 |

| Lag time 24 months | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 280 990/287 |

| Exposure | 1.22 [1.05; 1.41] | 355 115/526 |

* Lag time 1 year, fully adjusted for sex; age; polypharmacy (defined as prescription of five or more different drugs); prescription of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), non-ASA non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 5α-reductase inhibitors, statins, spironolactone, glucocorticoids for systemic use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy; the comorbidities diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and alcohol-related diseases; the Charlson comorbidity index (score); and prevalent valsartan use

95% CI, 95% confidence interval

The analysis of individual cancer types showed a significant association between potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan and liver cancer (adjusted HR 1.16 [1.03; 1.31], p = 0.017; Table 2). No association with potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan exposure was detected for any other cancer outcomes (table 3). The association with liver cancer remained stable after basic adjustment for age and gender (HR 1.20 [1.06; 1.35]) and also after additional adjustment for hepatitis (ICD-10 codes B15–B19) and other liver diseases (ICD-10 codes K70–K76, Z944). Following correction for age and gender there was an increase from 34.6 to 39.1 per 100 000 person-years in the incidence rate of liver cancer for the valsartan-exposed population above 40 years of age according to the 2011 German census. However, no dose-dependent effect on the risk of liver cancer was found for higher exposure to potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan (table 2). Varying lag times of 6 months to 2 years also did not alter the effect (etable 2). Evaluation of 3-year long-term use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan resulted in a decreased sample size (75 112 patients, 130 cases of liver cancer) and showed no significant association with liver cancer (adjusted HR 1.22 [0.80; 1.89]; Table 2). The incidence rates for exposure and no exposure are given in eTable 1 and Table 2.

Table 2. Liver cancer risk due to use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug products compared with uncontaminated valsartan.

| Hazard ratio [95% CI]*1 | Sample size/ Cancer cases | |

| Exposure to NDMA-contaminated valsartan | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 354 628/444 |

| Exposure | 1.16 [1.03; 1.31] | 385 167/736 |

| Exposure in dose categories | ||

| 0 to ≤ 90 DDD | 1.15 [0.98; 1.34] | 122 479/244 |

| > 90 to ≤ 170 DDD | 1.19 [1.02; 1.40] | 136 734/248 |

| > 170 DDD | 1.13 [0.97; 1.33] | 125 954/244 |

| NDMA exposure | ||

| Possible (contaminated valsartan batches < 75%) | 1.18 [1.01; 1.39] | 104 433/232 |

| Probable (contaminated valsartan batches ≥ 75%) | 1.15 [1.01; 1.31] | 280 734/504 |

| Long-term valsartan use*2 | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 61 236/102 |

| Exposure | 1.22 [0.80; 1.89] | 13 876/28 |

| Incidence rate per 100 000 person-years*3 | ||

| No exposure | 34.61 | |

| Exposure | 39.08 | |

*1 Lag time 1 year, fully adjusted for sex; age; polypharmacy (defined as prescription of five or more different drugs); prescription of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), non-ASA non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 5α-reductase inhibitors, statins, spironolactone, glucocorticoids for systemic use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy; the comorbidities diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and alcohol-related diseases; the Charlson comorbidity index (score); and prevalent valsartan use

*2 Long-term valsartan use is defined as valsartan prescription in at least nine quarters within the first 3 years of the study period.

*3 Standardized to the German population over 40 years in 2011 (e2)

DDD, Defined daily dose; NDMA, N-nitrosodimethylamine; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Table 3. Risk of individual cancers owing to use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug products compared with uncontaminated valsartan.

| Exposure to NDMA-contaminated valsartan | Hazard ratio [95% CI]*1 | Sample size/ Cancer outcomes |

| Outcome bladder cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 355 225/ 1041 |

| Exposure | 1.02 [0.95; 1.11] | 385 922/ 1491 |

| Outcome breast cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 208 262/ 1804 |

| Exposure | 1.02 [0.96; 1.08] | 242 778/ 2736 |

| Outcome colorectal cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 356 208/ 2024 |

| Exposure | 0.99 [0.94; 1.05] | 387 297/ 2866 |

| Outcome kidney cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 354 980/ 796 |

| Exposure | 0.96 [0.87; 1.05) | 385 522/ 1091 |

| Outcome lung cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 355 891/ 1707 |

| Exposure | 0.97 [0.91; 1.03] | 386 710/ 2279 |

| Outcome malignant melanoma | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 354 934/ 750 |

| Exposure | 0.94 [0.85; 1.03] | 385 414/ 983 |

| Outcome pancreatic cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 354 897/ 713 |

| Exposure | 0.93 [0.84; 1.02] | 385 398/ 967 |

| Outcome prostate cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 149 514/ 1788 |

| Exposure | 1.00 [0.94; 1.06] | 146 768/ 2379 |

| Outcome uterine cancer | ||

| No exposure | 1.00 (ref) | 206 944/ 486 |

| Exposure | 1.08 [0.96; 1.21] | 240 801/ 759 |

*1 Lag time 1 year, fully adjusted for sex; age; polypharmacy (defined as prescription of five or more different drugs); prescription of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), non-ASA non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 5α-reductase inhibitors, statins, spironolactone, glucocorticoids for systemic use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy; the comorbidities diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and alcohol-related diseases; the Charlson comorbidity index (score); and prevalent valsartan use

Discussion

In our study we observed a slight elevation in the risk of liver cancer with the use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan. Our analysis is based on a large longitudinal data set from a large statutory health insurance provider and on detailed information about potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan from the marketing authorization holders of valsartan drug products.

Comparison with other studies on valsartan exposure

Only one cohort study on this topic has been published to date (12); the Danish registry study by Pottegard et al. has only a small sample size, comprising 5150 persons with prescription of valsartan. Our study contains around 150 times more persons with valsartan prescription. Pottegard et al. examined effects on the overall cancer rate and individual cancers, finding no statistically significant associations (HR for cancer overall 1.09 [0.85; 1.41] (12). However, the number of cancer cases in the Danish study was limited (302 cancers overall; only eight cases each of kidney and bladder cancer). The statistical power for detection of small effects is therefore limited, and no precise statements on small effect sizes can be made. With regard to qualitative effects, our findings are in agreement with the Danish study, as we detected no modification of cancer risk by potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan for cancer overall or for the individual cancer types examined by the Danish authors.

For liver cancer, however, we observed a statistically significant association. This is interesting, as from a biological perspective liver cancer is the most likely form of cancer to resulting from NDMA contamination. That is the reason why we classified the occurrence of liver cancer as an independent primary endpoint compared with other specific types of cancer. Pottegard et al. did not report results for liver cancer, because no cases of liver cancer were detected among the persons who had received potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan in the Danish study (12).

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strength of our study is the cohort size of 780 871 persons with valsartan prescription and longitudinal health insurance claims data information from 2009 to 2017, drawn from the almost one third of the German population insured by the AOK (13, 14). This allowed us to perform analyses in an unselected patient population in a real-life setting, thus avoiding recall and selection bias. Another strength is that we received detailed information from the marketing authorization holders—e.g., which batches were produced with valsartan from Zhejiang Pharmaceuticals and how many packages were sold. These items of information are not included in the health insurance data. This enabled us to calculate the proportion of all batches with the relevant pharmaceutical registration numbers in Germany that contained potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan.

The study also features limitations. Because the study is based on observational health insurance claims data (i.e., on non-randomized data), we cannot rule out residual confounding. Although we adjusted our analysis by including numerous potential influencing factors, some risk factors for cancer, such as smoking habits, nutritional habits, and genetic predisposition, are not available in routine health insurance data and, therefore, could not be integrated into the analysis. Nevertheless, the frequency of unmeasured cancer risk factors should be similar in the NDMA-exposed and non-exposed groups. However, we cannot rule out unmeasured confounders such as group differences in adherence patterns, due for instance to polypharmacy or differences in the Charlson comorbidity index. Inclusion of prevalent users did not alter the result. We detected only marginal differences between results with basic adjustment for age and gender and the fully adjusted model with all covariates. This indicates that the potentially influential factors included in the model had no strong effects. Although detailed batch-wise information on potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan was provided, we had no information on the exact NDMA content of individual valsartan tablets. However, sensitivity analyses with varying degrees of possible or probable NDMA contamination yielded results comparable to those of the main analysis. A further limitation is that due to the limited follow-up time we were not able to monitor the long-term effects of NDMA-contaminated valsartan for more than 3 years.

Biological background

NDMA is classified by the IARC as probably carcinogenic (group 2A). It is carcinogenic in the tissues of experimental animal species with metabolism similar to that of human tissues (9, 15). Ingested NDMA is metabolized by cytochrome P450-dependent mixed-function oxidases to methyldiazonium ions, which alkylate proteins, DNA, and RNA (16– 19). In experimental animals oral NDMA exposure increases tumor incidences in various organs, predominantly in the liver (19). Those effects become measurable at doses of about 10 µg/kg/day (19). In our study, exposure to NDMA elevated liver cancer risk independent of dose. This might support the hypothesis of a threshold dose for the development of cancer. NDMA can be found among other N-nitroso compounds in foods, especially those that are smoked or dried at high temperature (20). Epidemiological studies investigating the association between explicit dietary NDMA exposure and cancer yielded inconclusive results (21– 23). No inferential statistical analyses were available on the association between human NDMA exposure and liver cancer. Nevertheless, exposure to NDMA-rich food in regions with high liver cancer rates in Thailand could potentially be based on a correlation, although no conclusive studies have been published (24). The observed rates of cancer overall and liver cancer in our study were around 1.5–2 times the national average. This is most likely due to the inclusion of persons aged 40 years and older for analysis, resulting in a study population older than the general population. The effect of NDMA exposure on liver cancer is a statistical result. However, molecular mechanisms known for NDMA in the pathogenesis of liver cancer in experimental animals support an association with NDMA exposure in humans. It may be that NDMA exposure promotes cancer development in already existing, as yet undiagnosed early stages and thus hastens clinical manifestation.

Regulatory and public health implications

Our study provides information for regulatory authorities worldwide to assess the public health impact of NDMA contamination in valsartan drug products. It is an example of how extensive real-world data from statutory health insurance funds can be used to examine urgent drug safety questions with pharmacoepidemiological methods. The immediate recall of all potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug products by regulatory authorities worldwide was necessary in order to protect public health. The detection of different nitrosamine impurities in drug products since 2018 led to the introduction of a new threshold by the European Medicines Agency (25).

Conclusion

We examined the association of NDMA-contaminated valsartan drug products and cancer risk in a large health insurance data set including more than 780 000 persons. We detected a small, yet statistically significant increase in the risk for liver cancer with the use of NDMA-contaminated valsartan while no association was found for overall cancer risk or other examined single cancer outcomes. However, the present study can only state the existence of a statistical association. Causality cannot be inferred. Long-term effects of regular use of potentially NDMA-contaminated valsartan for more than 3 years could not be evaluated because of the currently still relatively short follow-up time. Therefore, careful monitoring of potential further effects of NDMA-contaminated valsartan after longer periods is advisable.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Sample and data source

The data set from the AOK includes information on age, gender, outpatient and inpatient diagnoses (coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision with German modification, ICD-10-GM) and filled drug prescriptions (categorized according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system ATC code) on a quarterly basis for the years 2009–2017. During the period 2009–2017, on average nearly 25 million persons were insured by the AOK each year.

Selection criteria and diagnoses

Patients were continuously insured by the AOK during the years 2009–2013. Any diagnosis of cancer (ICD C00 to C97, except C44) in the years 2009–2013 led to exclusion from analysis. This ensures that only incident cancer cases occurring in 2014 or later are detected, since the likelihood of recurrence of cancer after 5 years or more without an intervening cancer diagnosis is considered low.

New cancer diagnoses were considered valid if they were main or secondary hospital diagnoses or were documented in the outpatient sector as verified or “status post” diagnoses. For the outpatient diagnoses, at least one confirmatory diagnosis within the following four quarters was required for validation. For the analysis of selected cancer diagnoses (bladder, breast, colorectal, kidney, liver, lung, melanoma, pancreatic, prostate, and uterine cancer) the cancer type had to be the first valid cancer diagnosis. Diagnoses of other cancer types were present only in the index quarter itself or later. The index quarter was defined as the quarter with the first valid cancer diagnosis following the cancer-free period from 2009 to at least the end of 2013. Persons with other cancer diagnoses before the index quarter in which the examined cancer type was diagnosed were not included in the analysis for the specific individual cancer types. The eFigure provides an overview of the study cohort for evaluation after application of the selection and quality control criteria.

Exposure

The NDMA content of valsartan tablets seems to correlate with the dose strength of the tablet (e1). Therefore, the valsartan doses of the contaminated drug products can be used to categorize NDMA exposure.

All users had a filled prescription of valsartan within the observation period. The observation period concluded at the end of 2017 at the latest. Prevalent valsartan use was defined as a filled valsartan prescription in the first quarter of 2012. Incident use started at the time of the first filled prescription during the study period. Patients were considered as exposed from the first filled prescription until the end of the observation period.

The marketing authorization holders provided batch-related data on all valsartan drug products for the years 2012–2017. This included detailed information on which batches were manufactured using the active ingredient valsartan supplied by Zhejiang Pharmaceuticals and how many packages of these drug products were sold. Based on this information, we calculated the proportion of all packages of valsartan drug products sold made up by packages manufactured using contaminated ingredients. We calculated this ratio for all pharmaceutical registration numbers (PZN) affected by the recalls of valsartan drug products. We were thus able to divide the PZN into possibly contaminated (< 75% of sold packages with contaminated valsartan) and probably contaminated (≥ 75% of sold packages with contaminated valsartan). It was also possible to calculate the amount of the defined daily dose (DDD) of contaminated valsartan drug products by multiplying the DDDs from the prescriptions with the previously calculated factors.

Because of the varying length of observation time, the use of cumulative doses may introduce bias. Therefore, we used dose categories and calculated the cumulative maximum of the dose as DDD in a given quarter within the observation time. The dose categories comprise the 33.3% and 66.6% percentiles of all non-zero maximum dose values. Dose categories were determined for the data set with a lag time of 1 year (four quarters) and were also used for sensitivity analyses. We calculated the DDD of contaminated valsartan by quarter and divided the patients into three equal groups with lowest, intermediate, or highest exposure based on the quarter of greatest exposure.

For the evaluation of long-term use of valsartan drug products, we used an exposure period of 3 years as baseline. Long-term use was defined as “patients with filled prescriptions in at least nine of the first twelve quarters (3 years) of the study period.” Users of uncontaminated valsartan did not receive any prescriptions of possibly or probably contaminated valsartan in the first 3 years and were right-censored at the first quarter in which they received any contaminated valsartan. Thus, for users of uncontaminated valsartan, only time periods of uncontaminated valsartan use were included in the analysis. Users of possibly or probably contaminated valsartan were defined as having filled prescriptions of contaminated valsartan in at least nine of the twelve quarters. Additional use of uncontaminated valsartan was allowed.

Forty-seven percent of patients receiving potentially contaminated valsartan and 67% of patients receiving uncontaminated valsartan received their second prescription of valsartan with the same contamination status in the following quarter. Sixty-nine percent and 88% of patients, respectively, received a repeat prescription within 1 year after the initial prescription or dropped out of the study. Eighty percent of patients receiving contaminated valsartan and 93% of patients receiving uncontaminated valsartan received a second prescription with the same contamination status within 2 years after the initial dose or dropped out of the study.

Covariates

The following time-dependent covariates were included in the statistical analyses as potential influencing factors: age, gender, polypharmacy (defined as prescription of five or more different drugs), comedications that are known or suspected to affect cancer risk, such as low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), non-ASA non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 5α-reductase inhibitors, statins, spironolactone, glucocorticoids for systemic use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy. Furthermore, we included the following comorbidities as additional potential influencing factors: diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, alcohol-related diseases, the Charlson comorbidity index (score), and presence of prevalent valsartan use at the beginning of the study period. Details of ATC and ICD-10 codes are given in eTable 3.

Statistical analyses

We applied Cox regression with time-dependent variables. We selected a lag time of 1 year, since short-term exposure is unlikely to modify the risk of cancer. For sensitivity analysis, we varied the lag time from 6 months to 2 years. In addition, there was a minimal observation time of 1 year before the lag time. For the evaluation of long-term use of valsartan drug products, patients with continuous valsartan prescription for at least 3 years were considered.

All calculations were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and were independently confirmed with R version 3.5.1. Any p-value < 0.05 (two tailed) was considered statistically significant. Hazard ratios (HR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals. Incidence rates were standardized using the 2011 German census for persons aged 40 years and over (e2).

eTable 3. ATC codes*1 and ICD-10 codes*2.

| Substance | ||

| Valsartan | ATC | C09CA03, C09DA03, C09DA23, C09DB01, C09DB08, C09DX01, C09DX02, C09DX04, C09DX05, C09DX10 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | ATC | B01AC06, B01AC30, B01AC34, B01AC36, B01AC56, B01AC86, C07FX02, C07FX03, C07FX04, C10BX01, C10BX02, C10BX04, C10BX05, C10BX06, C10BX08, C10BX12, N02BA01, N02BA51, N02BA71 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | ATC | M01A |

| 5α-Reductase inhibitors | ATC | G04CB01, G04CB02, G04CA51, G04CA52 |

| Statins | ATC | C10AA, C10BA, C10BX |

| Spironolactone | ATC | C03DA01, C03EC01, C03EC21, C03EC41, C03ED01 |

| Glucocorticoids | ATC | H02AB |

| Hormone replacement therapy | ATC | G03C excl. G03CD, G03DA, G03DB, G03DC, G03EA03, G03F |

| Selective serotonine reuptake inhibitors | ATC | N06AB, N06CA03 |

| Cancer outcomes | ||

| All cancer | ICD10 | C00–C96 excl. C44 |

| Colon cancer | ICD10 | C18–C20 |

| Liver cancer | ICD10 | C22 |

| Pancreatic cancer | ICD10 | C25 |

| Lung cancer | ICD10 | C34 |

| Malignant melanoma | ICD10 | C43 |

| Breast cancer | ICD10 | C50 |

| Uterine cancer | ICD10 | C54, C55 |

| Prostate cancer | ICD10 | C61 |

| Kidney cancer | ICD10 | C64 |

| Bladder cancer | ICD10 | C67 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | ICD10 | E10–E14 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ICD10 | J42–J44 |

| Congestive heart failure | ICD10 | I11.0, I13.0, I13.2, I42, I43, I50, I51.7 |

| Alcohol-related disease | ICD10 | E244, G31.2, G62.1, G72.1, I42.6, F10.2, K29.2, K70, K86.0, T51.9, Z502, Z72.0 |

*1 ATC codes according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system

*2 ICD-10 codes according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, German modification

eFigure.

Overview of study cohort after application of the selection and data quality control criteria

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Sarah Jewell, MD, for helping with the proofreading.

Data sharing statement

The data cannot be shared with or transmitted to third parties due to legal restrictions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/ AHA/ AAPA/ ABC/ ACPM/ AGS/ APhA/ ASH/ ASPC/ NMA/ PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018;12 doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2018.06.010. 579.e1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:776–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Medicines Agency. EMA reviewing medicines containing valsartan from Zhejiang Huahai following detection of an impurity. 2018. ( www.ema.europa.eu/news/ema-reviewing-medicines-containing-valsartan-zhejiang-huahai-following-detection-impurity), (last accessed on 31 July 2020) 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency. Update on review of valsartan medicines due to detection of NDMA. www.ema.europa.eu/news/update-review-valsartan-medicines-due-detection-ndma (last accessed on 31 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA updates and press announcements on angiotensin II receptor blocker recalls. 2018, 2019. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-and-press-announcements-angiotensin-ii-receptor-blocker-arb-recalls-valsartan-losartan (last accessed on 31 July 2020) 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency. Update on review of valsartan medicines following detection of impurity in active substance. www.ema.europa.eu/news/update-review-valsartan-medicines-following-detection-impurity-active-substance (last accessed on 31 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans. monographs.iarc.fr/list-of-classifications/ (last accessed on 31 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tricker AR, Preussmann R. Carcinogenic N-nitrosamines in the diet: occurrence, formation, mechanisms and carcinogenic potential. Mutat Res. 1991;259:277–289. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(91)90123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson LM, Souliotis VL, Chhabra SK, Moskal TJ, Harbaugh SD, Kyrtopoulos SA. N-nitrosodimethylamine-derived O(6)-methylguanine in DNA of monkey gastrointestinal and urogenital organs and enhancement by ethanol. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:130–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960328)66:1<130::AID-IJC22>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pottegård A, Kristensen KB, Ernst MT, Johansen NB, Quartarolo P, Hallas J. Use of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) contaminated valsartan products and risk of cancer: Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3851. k3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doblhammer G, Fink A, Zylla S, Willekens F. Compression or expansion of dementia in Germany? An observational study of short term trends in incidence and death rates of dementia between 2006/07 and 2009/10 based on German health insurance data. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7 doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0146-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundesgesundheitsministerium. Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung. Mitglieder, mitversicherte Angehörige und Krankenstand,Jahresdurchschnitt 2019. www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Statistiken/GKV/Mitglieder_Versicherte/KM1_JD_2019_bf.pdf (last accessed on 8 March 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Geneva: 1978. Some N-nitroso compounds. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Vol. 17, IARC, [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liteplo RG, Meek ME, Windle W. World Health Organization. Geneva: 2002. N-Nitrosodimethylamine Concise International Chemical Assessment Document (CICAD) 38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggerty HG, Holsapple MP. Role of metabolism in dimethylnitrosamine-induced immunosuppression: a review. Toxicology. 1990;63:1–23. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(90)90064-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee VM, Keefer LK, Archer MC. An evaluation of the roles of metabolic denitrosation and alpha-hydroxylation in the hepatotoxicity of N-nitrosodimethylamine. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:1319–1324. doi: 10.1021/tx960077u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peto R, Gray R, Brantom P, Grasso P. Dose and time relationships for tumor induction in the liver and esophagus of 4080 inbred rats by chronic ingestion of N-nitrosodiethylamine or N-nitrosodimethylamine. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6452–6469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scanlan RA. Formation and occurrence of nitrosamines in food. Cancer Res. 1983;43(5):2435s–2440s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y, Wang PP, Zhao J, et al. Dietary N-nitroso compounds and risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study in Newfoundland and Labrador and Ontario, Canada. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1109–1117. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng J, Stuff J, Tang H, Hassan MM, Daniel CR, Li D. Dietary N-nitroso compounds and risk of pancreatic cancer: results from a large case-control study. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:254–262. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakszyn P, González CA, Luján-Barroso L, et al. Red meat, dietary nitrosamines, and heme iron and risk of bladder cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:555–559. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitacek EJ, Brunnemann KD, Suttajit M, et al. Exposure to N-nitroso compounds in a population of high liver cancer regions in Thailand: volatile nitrosamine (VNA) levels in Thai food. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;37:297–305. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Medicines Agency. Nitrosamine impurities in human medicinal products. www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/nitrosamines-emea-h-a53-1490-assessment-report_en.pdf (last accessed on 31 October 2020) 1999 [Google Scholar]

- E1.Abdel-Tawab M, Gröner R, Kopp T, Meins J, Wübert J. Valsartan. ZL findet NMDA in Tabletten. Pharm Ztg. 2014;163:2072–2074. [Google Scholar]

- E2.Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. Zensus 2011. ergebnisse.zensus2011.de/#StaticContent:00,BEV_10_1,m,table (last accessed on 31 July 2020) 2018 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Sample and data source

The data set from the AOK includes information on age, gender, outpatient and inpatient diagnoses (coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision with German modification, ICD-10-GM) and filled drug prescriptions (categorized according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system ATC code) on a quarterly basis for the years 2009–2017. During the period 2009–2017, on average nearly 25 million persons were insured by the AOK each year.

Selection criteria and diagnoses

Patients were continuously insured by the AOK during the years 2009–2013. Any diagnosis of cancer (ICD C00 to C97, except C44) in the years 2009–2013 led to exclusion from analysis. This ensures that only incident cancer cases occurring in 2014 or later are detected, since the likelihood of recurrence of cancer after 5 years or more without an intervening cancer diagnosis is considered low.

New cancer diagnoses were considered valid if they were main or secondary hospital diagnoses or were documented in the outpatient sector as verified or “status post” diagnoses. For the outpatient diagnoses, at least one confirmatory diagnosis within the following four quarters was required for validation. For the analysis of selected cancer diagnoses (bladder, breast, colorectal, kidney, liver, lung, melanoma, pancreatic, prostate, and uterine cancer) the cancer type had to be the first valid cancer diagnosis. Diagnoses of other cancer types were present only in the index quarter itself or later. The index quarter was defined as the quarter with the first valid cancer diagnosis following the cancer-free period from 2009 to at least the end of 2013. Persons with other cancer diagnoses before the index quarter in which the examined cancer type was diagnosed were not included in the analysis for the specific individual cancer types. The eFigure provides an overview of the study cohort for evaluation after application of the selection and quality control criteria.

Exposure

The NDMA content of valsartan tablets seems to correlate with the dose strength of the tablet (e1). Therefore, the valsartan doses of the contaminated drug products can be used to categorize NDMA exposure.

All users had a filled prescription of valsartan within the observation period. The observation period concluded at the end of 2017 at the latest. Prevalent valsartan use was defined as a filled valsartan prescription in the first quarter of 2012. Incident use started at the time of the first filled prescription during the study period. Patients were considered as exposed from the first filled prescription until the end of the observation period.

The marketing authorization holders provided batch-related data on all valsartan drug products for the years 2012–2017. This included detailed information on which batches were manufactured using the active ingredient valsartan supplied by Zhejiang Pharmaceuticals and how many packages of these drug products were sold. Based on this information, we calculated the proportion of all packages of valsartan drug products sold made up by packages manufactured using contaminated ingredients. We calculated this ratio for all pharmaceutical registration numbers (PZN) affected by the recalls of valsartan drug products. We were thus able to divide the PZN into possibly contaminated (< 75% of sold packages with contaminated valsartan) and probably contaminated (≥ 75% of sold packages with contaminated valsartan). It was also possible to calculate the amount of the defined daily dose (DDD) of contaminated valsartan drug products by multiplying the DDDs from the prescriptions with the previously calculated factors.

Because of the varying length of observation time, the use of cumulative doses may introduce bias. Therefore, we used dose categories and calculated the cumulative maximum of the dose as DDD in a given quarter within the observation time. The dose categories comprise the 33.3% and 66.6% percentiles of all non-zero maximum dose values. Dose categories were determined for the data set with a lag time of 1 year (four quarters) and were also used for sensitivity analyses. We calculated the DDD of contaminated valsartan by quarter and divided the patients into three equal groups with lowest, intermediate, or highest exposure based on the quarter of greatest exposure.

For the evaluation of long-term use of valsartan drug products, we used an exposure period of 3 years as baseline. Long-term use was defined as “patients with filled prescriptions in at least nine of the first twelve quarters (3 years) of the study period.” Users of uncontaminated valsartan did not receive any prescriptions of possibly or probably contaminated valsartan in the first 3 years and were right-censored at the first quarter in which they received any contaminated valsartan. Thus, for users of uncontaminated valsartan, only time periods of uncontaminated valsartan use were included in the analysis. Users of possibly or probably contaminated valsartan were defined as having filled prescriptions of contaminated valsartan in at least nine of the twelve quarters. Additional use of uncontaminated valsartan was allowed.

Forty-seven percent of patients receiving potentially contaminated valsartan and 67% of patients receiving uncontaminated valsartan received their second prescription of valsartan with the same contamination status in the following quarter. Sixty-nine percent and 88% of patients, respectively, received a repeat prescription within 1 year after the initial prescription or dropped out of the study. Eighty percent of patients receiving contaminated valsartan and 93% of patients receiving uncontaminated valsartan received a second prescription with the same contamination status within 2 years after the initial dose or dropped out of the study.

Covariates

The following time-dependent covariates were included in the statistical analyses as potential influencing factors: age, gender, polypharmacy (defined as prescription of five or more different drugs), comedications that are known or suspected to affect cancer risk, such as low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), non-ASA non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 5α-reductase inhibitors, statins, spironolactone, glucocorticoids for systemic use, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and hormone replacement therapy. Furthermore, we included the following comorbidities as additional potential influencing factors: diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, alcohol-related diseases, the Charlson comorbidity index (score), and presence of prevalent valsartan use at the beginning of the study period. Details of ATC and ICD-10 codes are given in eTable 3.

Statistical analyses

We applied Cox regression with time-dependent variables. We selected a lag time of 1 year, since short-term exposure is unlikely to modify the risk of cancer. For sensitivity analysis, we varied the lag time from 6 months to 2 years. In addition, there was a minimal observation time of 1 year before the lag time. For the evaluation of long-term use of valsartan drug products, patients with continuous valsartan prescription for at least 3 years were considered.

All calculations were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and were independently confirmed with R version 3.5.1. Any p-value < 0.05 (two tailed) was considered statistically significant. Hazard ratios (HR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals. Incidence rates were standardized using the 2011 German census for persons aged 40 years and over (e2).