Abstract

A comprehensive SAR study of a putative TLR 3/8/9 agonist was conducted. Despite the excitement surrounding the potential of the first small molecule TLR3 agonist with a compound that additionally displayed agonist activity for TLR8 and TLR9, compound 1 displayed disappointing activity in our hands, failing to match the potency (EC50) reported and displaying only a low efficacy for the extent of stimulated NF-κB activation and release. The evaluation of >75 analogs of 1, many of which constitute minor modifications in the structure, failed to identify any that displayed significant activity and none that exceeded the modest activity found for 1.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor (TLR), TLR agonists, TLR3 agonist, SAR study

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a critical role in the mammalian defense against microbial infections.[1] The TLRs are germline-encoded receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), highly conserved molecular components present in microorganisms or abnormal cells, respectively.[2] Ligand induced TLR dimerization and activation marshals both the initial innate and slower adaptive immune response to protect the host from infectious pathogens[3,4,5] or remove abnormal cells. TLR activation for the treatment of infectious diseases or cancer have been widely explored where TLR agonists serve as attractive and efficacious vaccine adjuvants.[6–10] Despite their potential, there is not yet a wide range of small molecule TLR agonists available. Most bear poor structural, physical, or stability properties found in the identified naturally-occurring agonists that make them unattractive starting points for direct use or even further optimization.[11–17]

Humans possess several TLRs that are expressed heterogeneously in macrophages, dendritic cells, and other compartments. TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 are located on the cell membrane and bind bacterial lipids, peptidoglycans, lipoproteins and proteins, whereas TLRs 3, 7, 8 and 9 are situated in the endosome membrane within the cell and are activated by viral or bacterial nucleic acids. Complementing the selective targeting of a single TLR, multi-TLR-based therapies are an emerging area of research in oncology, as the simultaneous activation of multiple TLRs has potential merits. It can boost the immune response by triggering synergy between different TLR pathways.[18] TLRs are distributed heterogeneously and the effectiveness of a single TLR activation may be diminished if the target cells do not express a particular TLR. In contrast, if multiple TLRs are activated, they can complement each other for presentation and cross-presentation of antigens to T cells to enhance immunity. Pertinent to the work detailed herein, maturation of macrophage dendritic cells is promoted by TLR3 agonists in the tumor microenvironment, thus stimulating presentation/cross-presentation to T cells, resulting in expansion of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. On the other hand, TLR9 agonists target only plasmacytoid dendritic cells. As noted below, the first small molecule TLR3 agonist was recently disclosed that also acts on TLR9 and TLR8.[19]

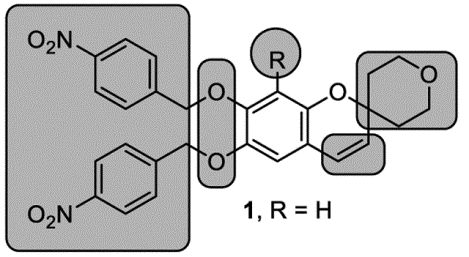

In the recent years, a still limited number of attractive small molecule TLR agonists have been described.[17] We reported the discovery of neoseptins,[20, 21] the first structurally characterized class of murine TLR4 agonists that bear no structural similarity to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or its active core Lipid A (LPA). More recently, we disclosed the discovery of the diprovocims,[22,23] a class of exceptionally potent, synthetic small molecule TLR2/TLR1 agonists that show efficacious adjuvant activity in an anticancer intramuscular vaccination against murine melanoma and protect mice from tumor rechallenge in an antigen specific manner.[24] In our continuing efforts, we were intrigued with the disclosure of compound 1, derived from a HTS screening lead by Yin.[19] It represents the first and only small molecule TLR3 agonist for a receptor that ordinarily senses viral double-stranded RNA.[25] It also acts as a multi-TLR agonist, activating TLRs 3/8/9.[19] The compound showed strong NF-κB activation through hTLR 3, 8 and 9 (EC50 = 4.8 μM, 13.4 μM and 5.7 μM, respectively) and negligible or no NF-κB activation via hTLR 2, 4, 5 and 7, enlisting a SEAP reporter assay and HEK293 cells overexpressing individually each of the hTLRs. It also exhibited significant cytotoxic activity, inhibiting the growth of cervical HeLa cancer cells (IC50 = 2.7 μM) by inducing apoptosis.

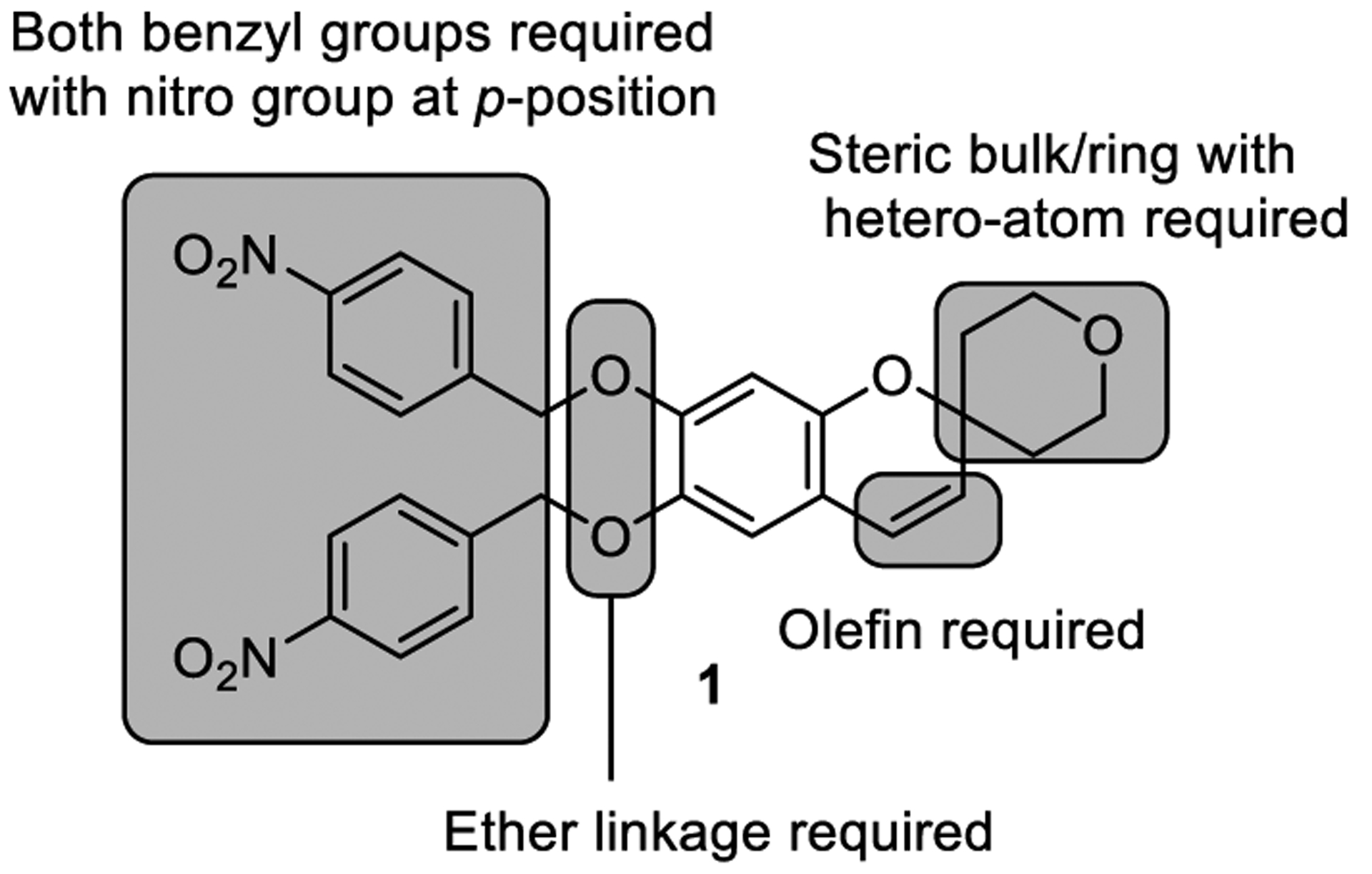

Based on the structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies disclosed by the Yin group,[19] both benzyl ether groups were required for the activity. An electron-withdrawing 4-nitro group was required, as its removal or even its relocation to the ortho or meta positions resulted in loss of activity. The chromene precursors, a chromanone or chromanol, did not display activity, underscoring the importance of the olefin. The benzyl ether linkage was also found to be important, as a decreased activity was observed when it was replaced with ester. Substitution, steric bulk, and optimally a spirocyclic ring, incorporating a heteroatom (the tetrahydropyran group) on the right side of the molecule was also essential to the activity. By building on the limited SAR reported by the Yin group, we hoped to discover compounds with improved potency and properties (solubility, selectivity, metabolic stability, toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and in vivo efficacy). Our initial objective was to confirm the activity and the mechanism of action of 1, followed by optimization of the compound potency.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry and SAR Study.

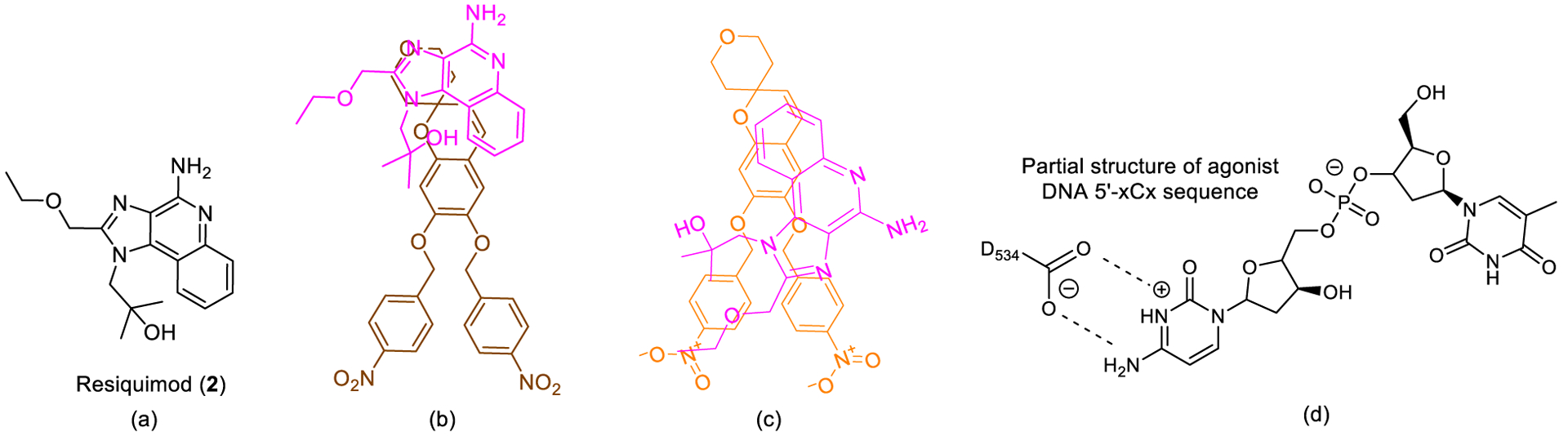

To establish insights into the binding of 1 to hTLR8, its structure was compared with resiquimod (2, R848), a known TLR8 agonist used as a control in TLR8 and TLR7 assays (Figure 2a), assuming it binds directly to TLR8 at the canonical small molecule agonist site. Resiquimod forms a salt bridge with Asp543 present in the agonist binding site (Supporting Information Figure 1). Docking studies and a simple overlay of 1 with R848 suggested that (1) the oxygen in the tetrahydropyran ring in 1 H-bonds to T574 (TLR8)/G565 (TLR9) backbone NHs, and (2) the two nitro groups are involved in polar interactions with multiple arginines and lysines (Supporting Information Figure 2a and b). Similar conclusions were drawn from a comparison of the putative binding of 1 to hTLR9 with that of 5’-xCx DNA, known TLR9 agonists (Supporting Information Figures 3 and 4),[26] where the cytosine group forms a salt bridge with Asp534 in the binding site (Figure 2d). We also inferred that the nitrophenyl groups in 1 are likely involved in pi-pi stacking interactions with the active site residues in TLR8. No small molecule bound structure is known for TLR3, making it difficult to assign putative binding site(s).[27]

Figure 2.

(a) Structure of resiquimod (2, R848). (b) 2D Binding overlay of 1 and resiquimod (pose 1). (c) 2D Binding overlay of 1 and resiquimod (pose 2). (d) Partial structure of 5’-xCx DNA, H-bonding to D534 in TLR9 agonist binding site.

Upon digesting the results of the Yin SAR studies, we elected to independently conduct (1) modifications of the benzyl groups with introduction of a variety of substituents that include nitro group bioisosteres and heterocyclic replacements of the phenyl ring to manipulate its electronic and lipophilic character, diminish its symmetrical nature, and introduce more sp3 character to improve solubility while enhancing activity. Independently we pursued (2) modification of the tetrahydropyran (THP) ring, and (3) examination of alternative substituted chromene scaffolds with potential introduction of more basic counterparts to enhance receptor binding and endosomal localization.

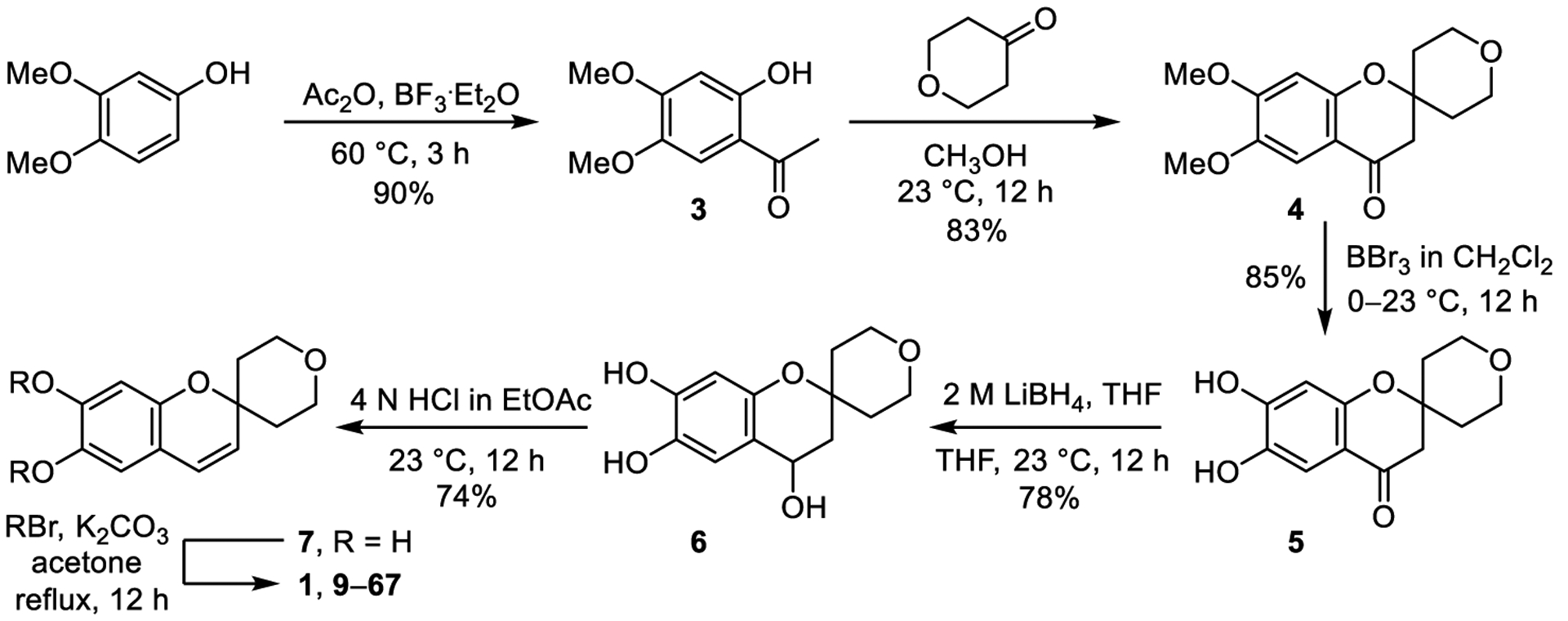

The synthesis of compounds 9–67 largely followed that detailed by Yin and is outlined in Scheme 1. Friedel-Crafts acylation of 3,4-dimethoxyphenol with acetic anhydride in presence of BF3·Et2O (60 °C, 3 h, 90%) yielded the acetophenone 3, which was condensed with tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one (methanol, 23 °C, 12 h, 83%) to obtain chromanone 4. Demethylation of 4 with boron tribromide in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (0 °C to 23 °C, 12 h, 85%) furnished catechol 5, and subsequent reduction with lithium borohydride (LiBH4, 2 M in THF, 23 °C, 12 h, 78%) afforded chromanol 6. The latter reduction with LiBH4 proved cleaner, easier to implement, and provided 6 in higher yield than that conducted with LiAlH4 as reported. Dehydration of 6 with 4 N HCl (ethyl acetate, 23 °C, 12 h, 74%) yielded chromene 7 and was much cleaner than the reported dehydration conducted in acetone. Compound 7 was alkylated with the corresponding benzylic bromides (K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 12 h) to furnish compounds 1 and 9–67.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1 and 9–67

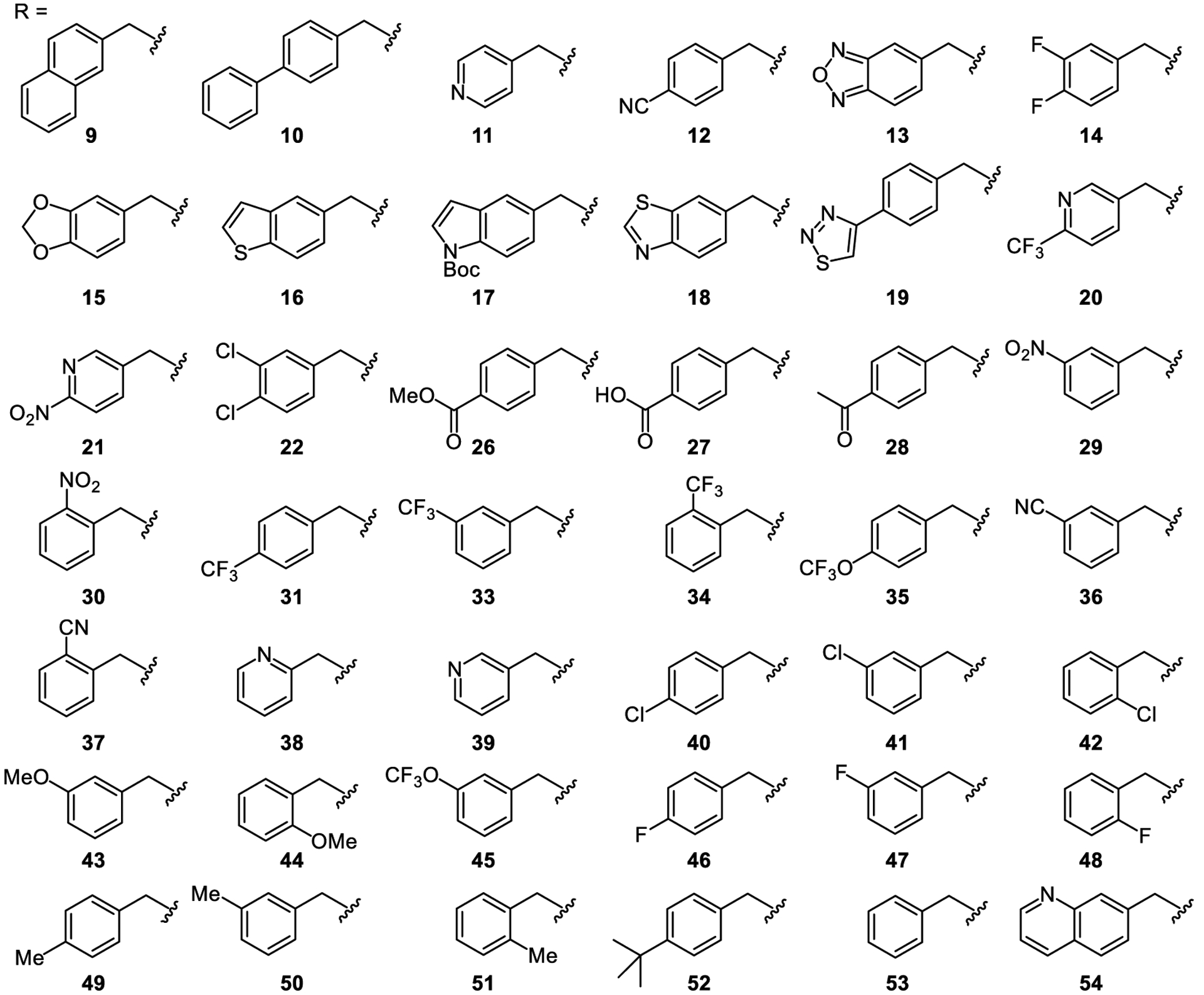

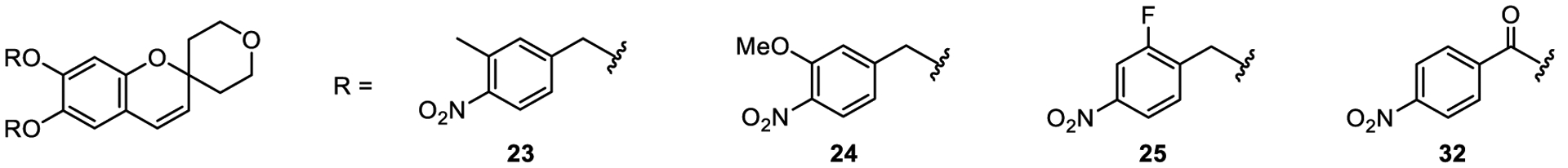

We replaced the 4-nitro group with bioisosteres, including a nitrile and oxadiazole (compounds 12 and 13, respectively). In addition, a series of heterocyclic, halogenated and other substituted derivatives (compounds 14–22, 31–34, 39–48) were prepared in efforts to replace the 4-nitro group on the benzyl substituent (Figure 3). Several disubstituted benzyl derivatives containing the 4-nitro group were also synthesized (Figure 4, 23–25), and the p-nitrophenyl group was replaced with a variety of additional bioisosteres (compounds 26–28). In order to promote possible pi-pi stacking, other electron-deficient aryls and indoles were also examined (compounds 9–11, 17, 18, 38, 39, 54).[28] In addition, the 4-nitrobenzyl ether was also replaced with a 4-nitrobenzoyl group (32). However, all compounds described above displayed little or no activation of TLR 8 and 9 compared to lead compound 1. As expected, substituents at the meta-position did not result in an improvement in activity (e.g., compound 29). Introduction of alkyl substituents (49–52) also did not enhance activation.

Figure 3.

Structures of compounds 9–22, 26–54.

Figure 4.

Structures of 23–25, disubstituted benzyl derivatives containing a 4-nitro group, and 4-nitrobenzoyl derivative 32.

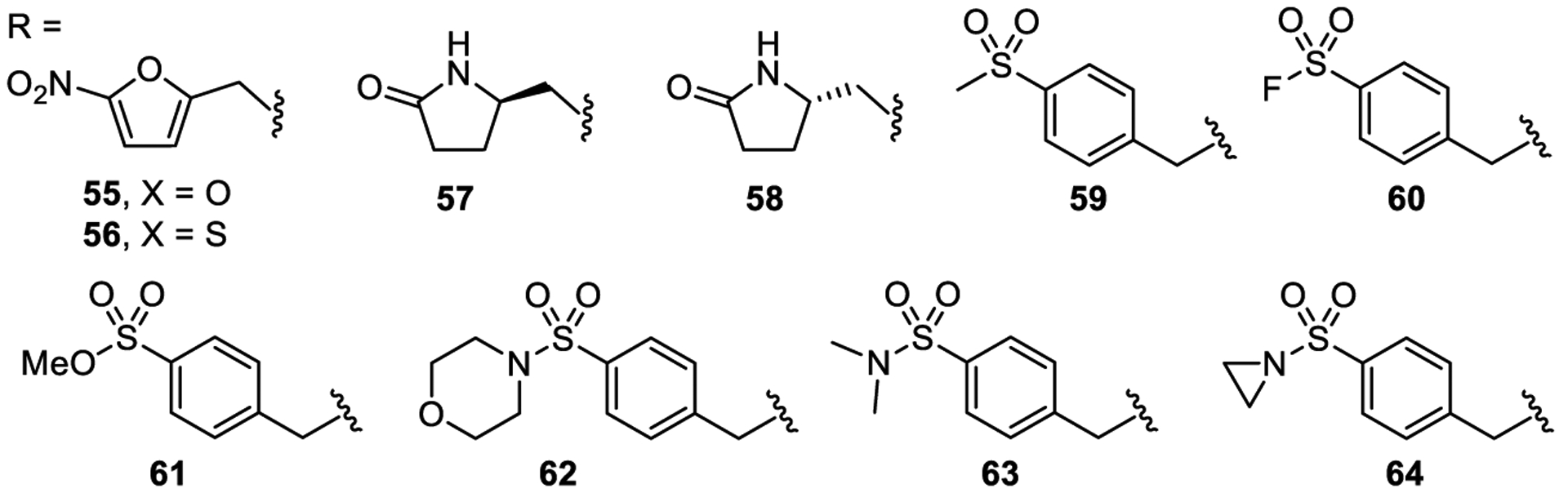

5-Nitrofuranyl (55, cLogP = 4.0) and 5-nitrothienyl (56, cLogP = 5.2) replacements of the 4-nitrophenyl ring with cLogP values [29] more favorable or close to that of the lead molecule (1, clogP = 5.5) were synthesized (Figure 5). Additionally, a series of sulfonyl derivatives 59–64 (cLogP ca. 3) were prepared to address the high lipophilicity of the lead molecule (cLogP of compound 1 is 5.5) while simultaneously maintaining potential binding interactions of the nitro group. In order to introduce sp3 character, and potentially improve solubility, derivatives were prepared that contain each enantiomer of the pyrrolidin-2-one substituent (57 and 58). Unfortunately, none of these compounds resulted in activation of TLR 8 and 9.

Figure 5.

Structures of compounds 55–64.

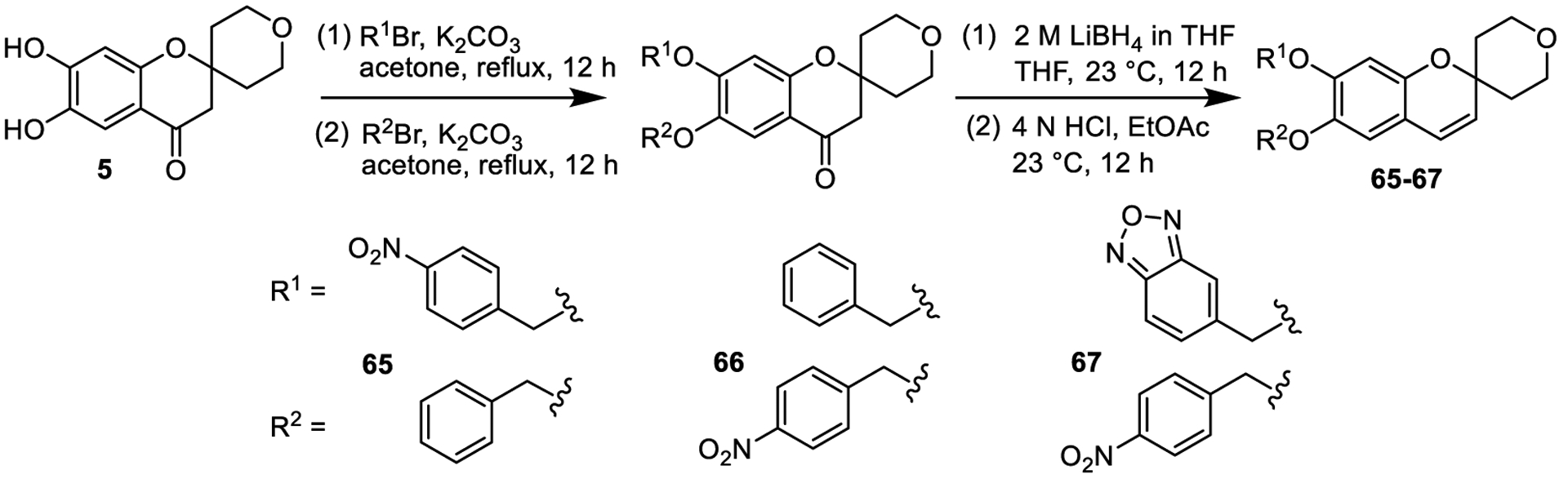

The necessity of each individual 4-nitro substituent on the two benzyl groups was also defined. Based on docking studies and overlay models of 1 with resiquimod, it is possible only the one nitro group of the 4-nitrophenyl group that potentially interacts with a tyrosine residue (Y348) in the resiquimod binding site is needed (Supplementary Figure 2c). Therefore, analogs of 1 that possess a single 4-nitro group on each of the benzyl substituents were prepared and examined (Figure 6, compounds 65 and 66). The synthesis of these unsymmetrical derivatives is shown in Figure 6. In addition, we replaced the 4-nitro group of one of the benzyl groups with a fused oxadiazole as a potential bioisostere for the nitro group while maintaining the one putative key 4-nitrophenyl group (compound 67). However, compounds 65–67 were inactive, indicating that each 4-nitro group plays an important role in lead compound 1.

Figure 6.

Preparation and structure of unsymmetrical derivatives.

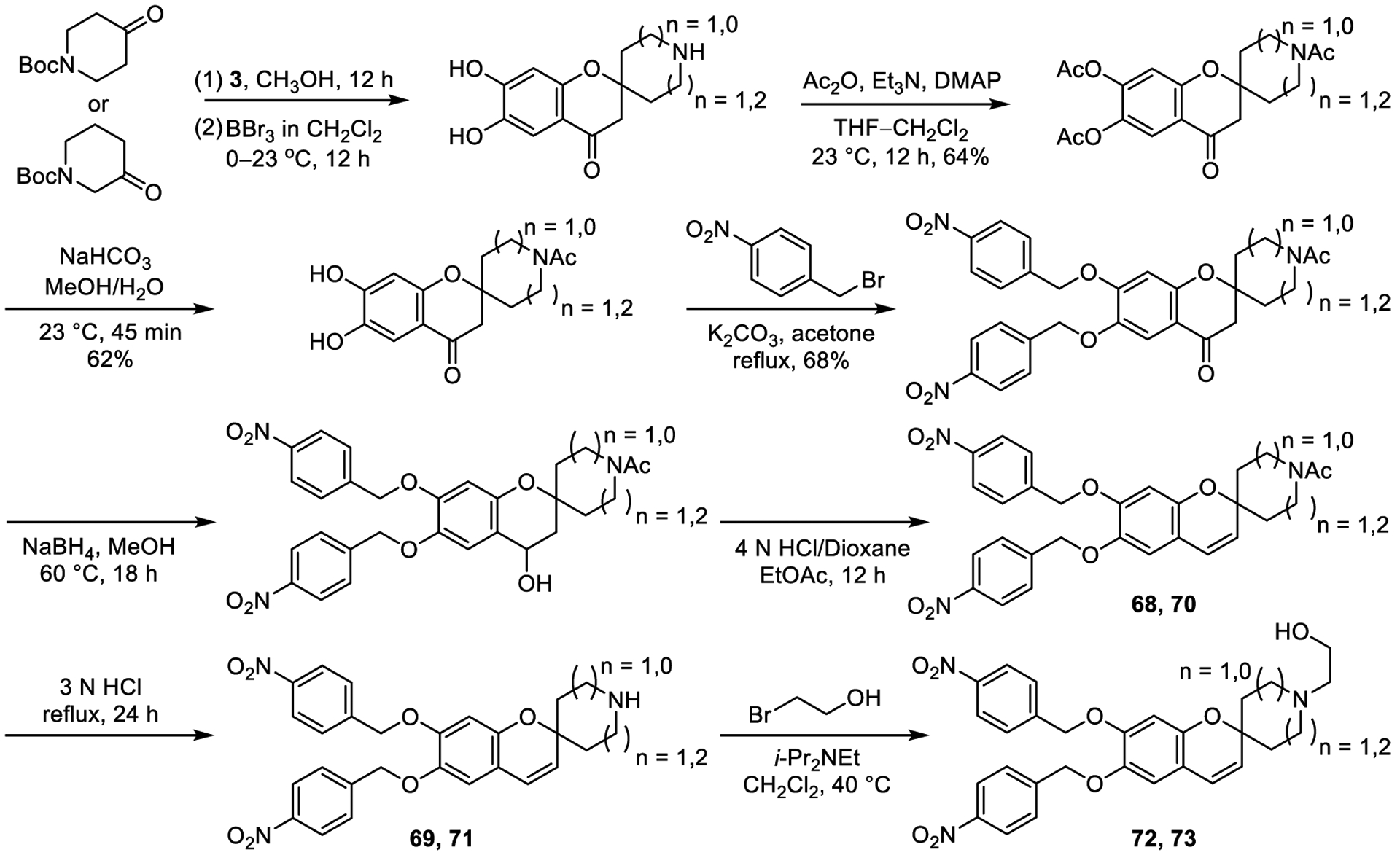

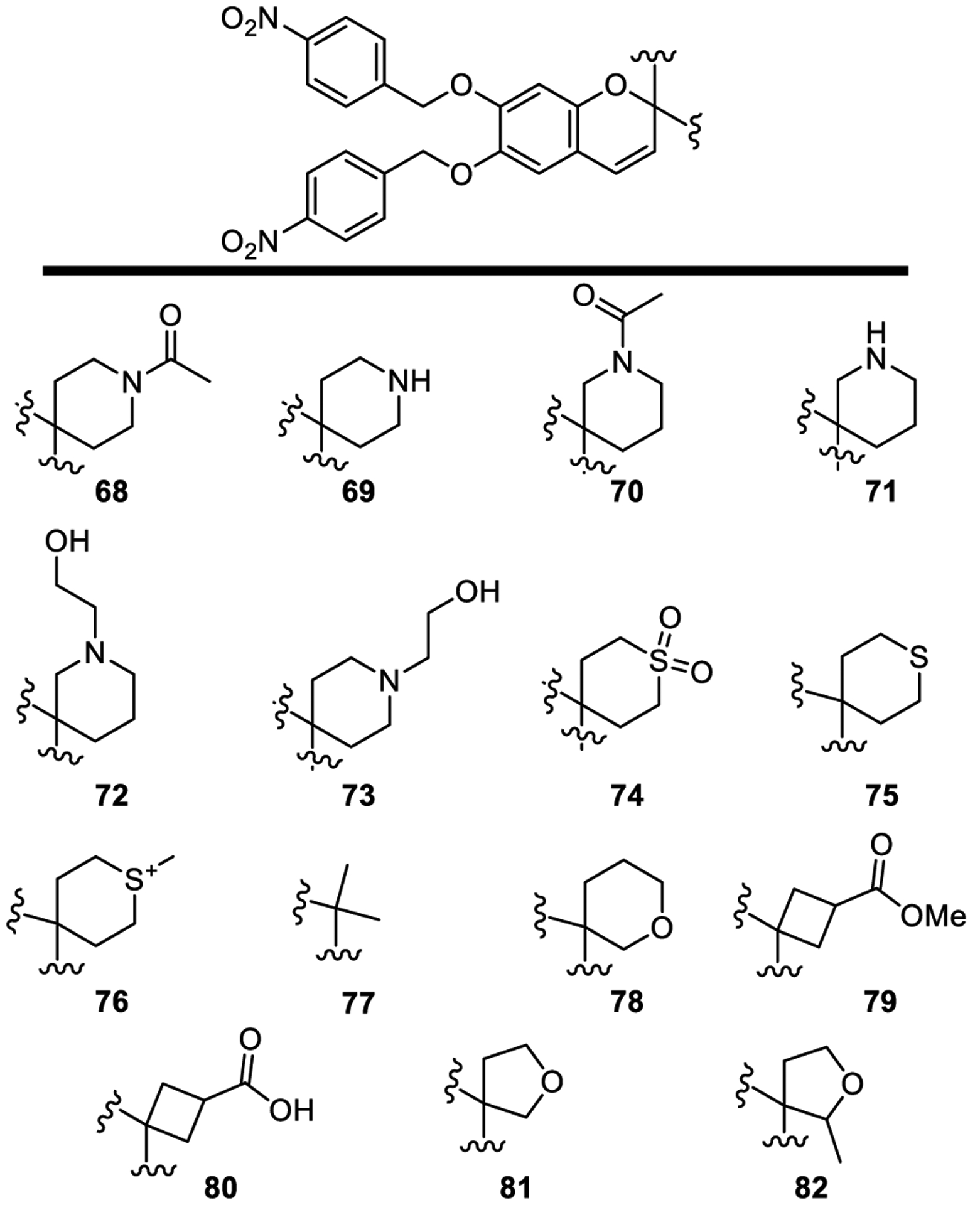

A final set of modifications of the lead candidate 1 targeted the spirocyclic tetrahydropyran (THP) ring. In a subset of these studies, the tetrahydropyran was replaced with two isomeric piperidine rings (Scheme 2 and Figure 7, 68–71) with the goal to (1) improve solubility, (2) potentially provide endosomal delivery, localization, or trap, (3) improve receptor interactions directly or indirectly through attached side chains, and (4) provide a site for conjugation to neo-antigens and proteins or antibodies for targeted delivery. The introduction of a complementary basic atom could also form a salt bridge with D543 in TLR8 and D534 in TLR9. A 2-hydroxyethyl substituent was appended to the nitrogen to attenuate the amine basicity and potentially mimic the five-atom chain in R848, binding in a narrow pocket in TLR8 (compounds 72 and 73).

Scheme 2.

Preparation of candidate agonists with a piperidine subunit

Figure 7.

Structures of compounds 68–82.

The six-membered 4-THP spirocyclic ring was replaced with spirocyclic rings of altered sizes and modified heteroatoms (Figure 7), including the 4-thiopyran dioxide (74), 4-thiopyran (75) and its methyl sulfonium salt (76), quaternary dimethyl substitution (77, original screening lead [19]), regioisomers of 4-THP (78), ring contracted versions of the 4-THP (79 and 80, tetrahydrofurans 81 and 82). However, none of the modifications improved TLR activation. Compounds 74–82 or their precursors were prepared by the route outlined in Scheme 1, introducing the modifications in the condensation of 3 with the corresponding ketone.

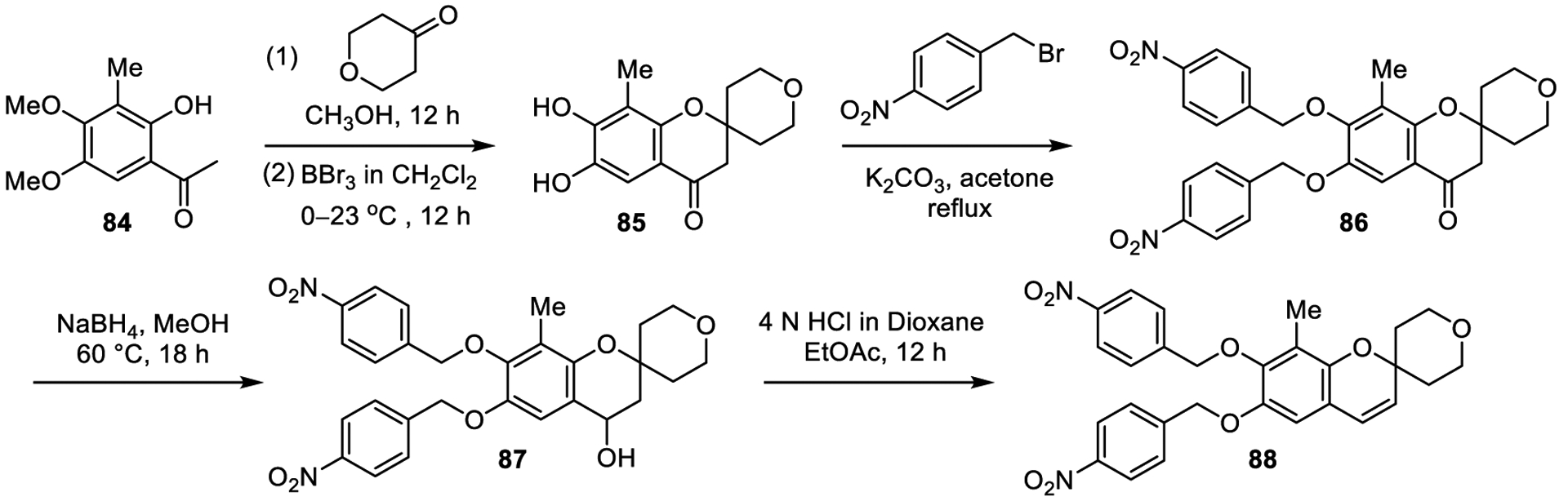

With the aim of restricting the spatial orientation of the nitrophenyl groups and in efforts to explore a site for additional receptor interactions of the chromene, compound 88 was prepared and contains a C8-methyl substituent attached to the core benzene ring. The known compound 84 was converted to chromanone 86, which was reduced to chromanol 87, followed by dehydration to afford chromene 88 (Scheme 3). None of the three compounds (86, 87 and 88), including 88 possessing a single added methyl group relative to 1, exhibited any TLR activation.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compound 88

Biological Evaluation.

The Yin group reported that compound 1 showed strong NF-κB activation in a reporter assay through activation of hTLR 3, 8, and 9 (EC50 = 4.8 μM, 13.4 μM and 5.7 μM, respectively).[19] In contrast, compound 1 prepared herein at two different sites and by two different procedures and assessed multiple times only showed weak activity for NFĸB activation in our hands, with EC50s of 22, 27 and 58 μM for TLRs 3, 8 and 9, respectively. Because of expectations of improvements in the modest activity reported for 1, the analogues were examined at concentrations up to 5 μM. However, none of the analogs of 1 prepared showed an improvement in activity, with essentially all compounds being inactive and with all EC50 values being greater than 5 μM (Supporting Information Tables 1 and 2). Selected members of the full set (13, 18, 24, 55, 56 and 69) were rescreened at concentrations up to 100 μM and, with the exception of 69, were inactive (EC50 >100 μM) and displayed no NFĸB activation. Compound 69 (with a piperidine ring replacing the tetrahydropyran ring) exhibited a weak EC50 of 111 μM in TLR9, but no activity (>125 μM) in TLR8. Consistent with reported results with 1,[19] neither compound 1 nor any of its analogs showed any activity with TLR7.

We also measured the stimulated release of the cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) by the action of 1 in both mouse macrophages and in partially differentiated human THP-1 cells as described in our prior studies.[20–24] It showed no activity in mouse macrophages and very weak activity in human THP-1 cells, where the weak stimulated TNF-α release continues to rise slowly up to 100 μM, the highest concentration examined (EC50 >100 μM). The extent of this stimulated release was not at a level that we would consider active in this sensitive assay using native cells. This contrasts the reported strong production of TNF-α in THP-1 cells by the Yin group (EC50 5–10 μM).[19] Thus, although the differences in the potency of 1 in the reporter assays for hTLR 3, 8, and 9 (2- to 10-fold) might be attributable to subtle differences in the assay implementation, those observed with human THP-1 cells cannot.

Conclusions

A comprehensive SAR study of a putative TLR 3/8/9 agonist was conducted. Despite our excitement with the potential of the first small molecule TLR3 agonist with a compound that additionally displayed agonist activity at TLR8 and TLR9, compound 1 displayed disappointing activity in our hands, failing to match the potency (EC50) reported and displaying only a low efficacy for the extent of stimulated NF-κB release. The evaluation of >75 analogs of 1, many of which constitute minor modifications in its structure, failed to identify any that displayed significant activity and none that exceeded the modest activity we found for 1 or that was initially reported. Although the authors of the original work [19] have not responded to our requests for guidance on their report of more promising observations with 1, it is possible that it could be related to the low solubility of the lead candidate compound and potential that compound aggregates may have been assessed in the original work.

Methods and Materials

Experimental.

All reagents and solvents were used as supplied without further purification unless otherwise noted. All reactions were performed in anhydrous solvents unless otherwise noted. CHCl3 was pre-treated with alumina for at least 24 h prior to use. Preparative TLC (PTLC) and column chromatography were conducted using Millipore SiO2 60 F254 PTLC (0.5 mm) and Zeochem ZEOprep 60 ECO SiO2 (40–63 μm), respectively. Analytical TLC was conducting using Millipore SiO2 60 F254 TLC (0.250 mm) plates. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker Avance III HD 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with either a 5 mm QCI or 5 mm CPDCH probe or a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm BBFO probe. IR spectra were obtained using a Thermo Nicolet 380 FT-IR with a SmartOrbit Diamond ATR accessory. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed by direct sample injection on an Agilent G1969A ESI-TOF mass spectrometer.

Candidate agonist synthesis.

1-(2-Hydroxy-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)ethan-1-one (3).

A solution of 3,4-dimethoxyphenol (2 g, 12.97 mmol) in acetic anhydride (5 mL) under N2 was treated with BF3·Et2O (1.3 mL mg, 1.3 mmol) at 0 °C for 10 min, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 3 h. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and neutralized with the addition of saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution, followed by extraction with ethyl acetate. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc/hexane 2:3) to give 3 (2.3 g, 90%) as a white solid: mp 103–104 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.66 (s, 1H), 7.06 (s, 1H), 6.46 (s, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 2.57 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 202.1, 160.1, 156.8, 111.7, 111.6, 100.5, 56.7, 6.2, 26.4. MS (ESI) calcd for C15H19O5 [M+H]+, 197.1; found, 197.1.

6,7-Dimethoxy-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetrahydrospiro[chromane-2,4′-pyran]-4-one (4).

A solution of 3 (2.0 g, 10.2 mmol) in methanol was treated sequentially with pyrrolidine (0.84 mL, 10.2 mmol) and tetrahydro-4H-pyran-4-one (3.06 g, 30.6 mmol), and the reaction mixture was warmed at reflux for 12 h. Purification by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc/hexane 1:4) gave 4 (2.35 g, 83%) as a yellow solid: mp 124–125 °C: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29 (s, 1H), 6.49 (s, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.89 – 3.77 (m, 4H), 2.71 (s, 2H), 2.05 – 1.99 (m, 2H), 1.79 (ddd, J = 14.2, 11.0, 5.0 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI) calcd for C15H19O5 [M+H]+, 279.1; found, 279.1.

6,7-Dihydroxy-2′,3′,5′,6′-tetrahydrospiro[chromane-2,4′-pyran]-4-one (5).

A solution of 4 (0.5 g, 1.8 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was slowly treated with boron tribromide (1 M in CH2Cl2, 5.4 mL, 5.4 mmol) at 0 °C under nitrogen, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 12 h. The reaction mixture was poured into ice water and extracted with EtOAc, (3x). The combined organic layers were dried with Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc/hexane 4:1) to give 5 (383 mg, 85%) as an off-white solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.22 (s, 1H), 9.05 (s, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 3.68 – 3.61 (m, 4H), 2.65 (s, 2H), 1.81 (dt, J = 13.8, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 1.68 (ddd, J = 14.4, 9.3, 6.1 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI) calcd for C13H15O5 [M+H]+, 251. 1; found, 251.1.

2′,3′,5′,6′-Tetrahydrospiro[chromane-2,4′-pyran]-4,6,7-triol (6).

A mixture of 5 (500 mg, 2 mmol) and 2 M LiBH4 in THF (2 mL, 4 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was stirred at 23 °C for 6 h. The solution was quenched with the addition of methanol, and the reaction mixture was adjusted to pH 1–2 with the addition of aqueous 2 N HCl prior to removal of solvents under reduced pressure. The residue was extracted with EtOAc (10 mL) and washed sequentially with water and saturated aqueous NaCl. The organic phase was dried with Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc) to afford 6 (393 mg, 78%) as a yellow solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.12 (s, 1H), 9.05 (s, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.46 (br s, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 4.78 – 4.75 (m, 1H), 3.68 – 3.61 (m, 4H), 2.65 (s, 2H), 1.81 (dt, J = 13.8, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 1.68 (ddd, J = 14.4, 9.3, 6.1 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI) calcd for C13H17O5 [M+H]+, 253.1; found, 253.1.

2′,3′,5′,6′-Tetrahydrospiro[chromene-2,4′-pyran]-6,7-diol (7).

Compound 6 (200 mg, 0.79 mmol) was dissolved in ethyl acetate (1 mL), and aqueous 4 N HCl (0.4 mL,1.58 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 12 h, and then basified with the addition of saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (3 mL) followed by extraction with EtOAc (10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried with Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated, and purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc/hexane 1:3) to afford 7 (137 mg, 74%) as an off white solid: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.15 (s, 1H), 9.15 (s, 1H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 6.48 (s, 1H), 6.29 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 5.51 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (td, J = 11.2, 2.6 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (dt, J = 11.5, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 1.96 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 2H), 1.77 (td, J = 10.2, 5.4 Hz, 2H). MS (ESI) calcd for C13H15O4 [M+H]+, 235.1; found, 235.1.

Synthesis of compounds 9–64, General procedure.

A mixture of 7 (10 mg, 0.043 mmol) and K2CO3 (35.4 mg, 0.26 mmol) in acetone (1 mL) was treated with the aryl bromide (0.093 mmol) and stirred at 60 °C under nitrogen for 12 h. The reaction mixture was filtered, concentrated, and purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc/hexane) to afford compounds 1 and 9 – 64.

The characterization for 1, 9–64 is provided in the Supporting Information section. Experimental procedures for adaptations of the general procedure and characterization data for the synthesis 65–67 (Figure 6), 68–73 (Scheme 2), 74–82 (Figure 7), and 86–88 (Scheme 3) are also provided in Supporting Information.

In vitro human TLR cell reporter assays.

Human HEK-blue reporter cells (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) containing a TLR transgene are plated on day 0 at an optimal cell concentration per well of a 384-well plate (20 uL cells/well) and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Compounds are added (100 nL/well) to each well using an ATS liquid handling instrument (Wagner Life Science, Middleton, MA) and the mixtures are incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Freshly prepared Q-Blue reagent (Invivogen, San Diego, CA; suspended in water) is added to each well (10 uL/well) and the mixtures are incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 30 min before measuring the absorbance (620 nm) using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA). Assay baselines are set using relative light unit (RLU) values from DMSO-treated control cells and 100% is set using reference agonist RLU values from cells treated at the highest compound concentration [reference agonists: poly I:C HMW (TLR3), resiquimod (TLR7, TLR8) and ODN-2006 (TLR9)]. Effective concentration values (EC50; compound concentration yielding half-maximal response) are calculated using BMS proprietary data analyses software.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Structure of reported TLR 3/8/9 agonist and summary of prior SAR (ref 19).

Acknowledgements.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of NIH (CA042056, D.L.B.) and Bristol Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest beyond the disclosed interest of Bristol Meyers Squibb (coauthors) in supporting and collaborating in the work.

References

- 1.Ferrandon D, Imler JL, Hoffmann JA. Sensing infection in Drosophila: Toll and beyond. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeway CA Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takuechi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moresco EM, LaVine D, Beutler B. Toll-like receptors. Curr Biol 2011;21:R488–R493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang JY, Lee JO. Structural biology of the Toll-like receptor family. Annu Rev Biochem 2011;809:917–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutler B Neo-ligands for innate immune receptors and the etiology of sterile inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007;13:552–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennessy EJ, Parker AE, O’Neill LA. Targeting Toll-like receptors: emerging therapeutics? Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly DJ, O’Neill LA. New developments in Toll-like receptor targeted therapeutics. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12:510–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoebe K, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Tabeta K, Janssen E, Du X, Beutler B. TLR signaling pathways: opportunities for activation and blockade in pursuit of therapy. Curr Pharmaceut Des. 2006;12:4123–4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czarniecki M Small molecule modulators of Toll-like receptors. J Med Chem. 2008;51:6621–6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer T, Stockfleth E. Clinical investigations of Toll-like receptor agonists. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2008;17:1051–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Smith C, Yin H. Targeting Toll-like receptors with small molecule agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:4859–4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peri F, Calabrese V. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) modulation by synthetic and natural compounds: An update. J Med Chem. 2014;57:3612–3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Lu BL, Williams GM, Brimble MA. TLR2 Agonists and their structure–activity relationships. Org Biomol Chem. 2020;18:5073–5094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kaur A, Kaushik D, Piplani S, Mehta SK, Petrovsky N, Salunke DB. TLR2 Agonistic small molecules: detailed structure–activity relationship, applications, and future prospects. J Med Chem. 2021;64:233–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federico S, Pozzetti L, Papa A, Carullo G, Gemma S, Butini S, Campiani G, Relitti N. Modulation of the innate immune response by targeting Toll-like receptors: A perspective on their agonists and antagonists. J Med Chem. 2020;63:13466–13513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajishangallis G, Lambris JD. More than complementing Tolls: complement–Toll-like receptor synergy and crosstalk in innate immunity and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2016;274:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Dewan V, Yin H. Discovery of small molecules as multi-Toll-like receptor agonists with proinflammatory and anticancer activities. J Med Chem. 2017;60:5029–5044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Su L, Morin MD, Jones BT, Whitby LR, Surakattula MM, Huang H, Shi H, Choi JH, Wang KW, Moresco EM, Berger M, Zhan X, Zhang H, Boger DL, Beutler B. TLR4/MD-2 activation by a synthetic agonist with no similarity to LPS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E884–E893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin MD, Wang Y, Jones BT, Su L, Surakattula MM, Berger M, Huang H, Beutler EK, Zhang H, Beutler B, Boger DL. Discovery and structure-activity relationships of the neoseptins: A new class of Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) agonists. J Med Chem 2016;59:4812–4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morin MD, Wang Y, Jones BT, Mifune Y, Su L, Shi H, Moresco EMY, Zhang H, Beutler B, Boger DL. Diprovocims: A new and exceptionally potent class of toll-like receptor agonists. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:14440–14454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su L, Wang Y, Wang J, Mifune Y, Morin MD, Jones BT, Moresco EMY, Boger DL, Beutler B, Zhang H. Structural basis of TLR2/TLR1 activation by the synthetic agonist diprovocim. J Med Chem. 2019;62:2938–2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Su L, Morin MD, Jones BT, Mifune Y, Shi H, Wang K, Zhan X, Liu A, Wang J, Li X, Tang M, Ludwig S, Hildebrand S, Zhou K, Siegwart D, Moresco EMY, Zhang H, Boger DL, Beutler B. Adjuvant effect of the novel TLR1/2 agonist Diprovocim synergizes with anti-PD-L1 to eliminate melanoma in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E8698–E8706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohto U, Ishida H, Shibata T, Sato R, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Toll-like receptor 9 contains two DNA binding sites that function cooperatively to promote receptor dimerization and activation. Immunity. 2018;48:649–658.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choe J, Kelker MS, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of human toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) ectodomain. Science. 2005;309:581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bissantz C, Kuhn B, Stahl M. A medicinal chemist’s guide to molecular interactions. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5061–5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.cLogP values were calculated with the module within ChemDraw Professional 16.0.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.