Abstract

Background:

Policies aimed at addressing the high rates of opioid overdose have prioritized increasing access to medications for treatment of opioid use disorder (MOUD). Numerous barriers exist to providing MOUD within the criminal justice system and/or to justice-involved populations. The aim of this study was to conduct a scoping review of the peer-reviewed literature on implementation of MOUD within criminal justice settings and with justice-involved populations.

Methods:

A systematic search process identified 53 papers that addressed issues pertaining to implementation barriers or facilitators of MOUD within correctional settings or with justice-involved populations; these were coded and qualitatively analyzed for common themes.

Results:

Over half of the papers were published outside of the U.S. (n = 28); the most common study designs were surveys or structured interviews (n = 20) and qualitative interviews/focus groups (n = 18) conducted with correctional or treatment staff and with incarcerated individuals. Four categories of barriers and facilitators were identified: institutional, programmatic, attitudinal, and systemic. Institutional barriers typically limited capacity to provide MOUD to justice-involved individuals, which led to programmatic practices in which MOUD was not implemented following clinical guidelines, often resulting in forcible withdrawal or inadequate treatment. These programmatic practices commonly led to aversive experiences among justice-involved individuals, who consequently espoused negative attitudes about MOUD and were reluctant to seek treatment with MOUD following their release to the community. Facilitators of MOUD implementation included increased knowledge and information from training interventions and favorable prior experiences with individuals being treated with MOUD among correctional and treatment staff. Few systemic facilitators to implementing MOUD with justice-involved individuals were evident in the literature.

Conclusion:

Barriers to implementing MOUD in criminal justice settings and/or with justice-involved populations are pervasive, multi-leveled, and inter-dependent. More work is needed on facilitators of MOUD implementation.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, medication, criminal justice system, implementation, barriers, facilitators

1. Background

Current policy initiatives to address the high rates of opioid use, overdose, related physical health harms (e.g., abscesses, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, sepsis), and fatalities focus on the expansion of treatment capacity to deliver medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) as the standard of care for treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD; Blanco & Volkow, 2019; National Academies of Sciences, 2019). These include treatment with methadone, an opioid agonist; buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist; and naltrexone, an opioid antagonist (Bart, 2012). Within this context, a priority has been placed on expanding the provision of MOUD within the criminal justice system and to justice-involved populations, given that use of opioids increases the likelihood of contact with the criminal justice system, with increasing severity of opioid use associated with greater risk of criminal justice system involvement (Winkelman, Chamg, & Binswanger, 2018).

Prior studies have established that MOUD for justice-involved individuals with OUD has beneficial effects on their criminal justice outcomes and on their risk of opioid-related overdose and death following release. Farrell-MacDonald, MacSwain, Cheverie, Tiesmaki, and Fischer (2014) assessed the impact of methadone treatment on post-release criminal re-offending and correctional readmission. Patients continuing on methadone had a 65% lower risk of returning to custody than a group that terminated treatment post-release and a group of non-methadone controls with OUD. In a randomized controlled trial of extended release naltrexone injection versus treatment as usual, Murphy et al. (2017) found the mean number arrests at 78-week follow up was significantly lower in the naltrexone patients. Moreover, several studies demonstrate the benefits of continuing treatment with MOUD, both at the time of incarceration for individuals currently receiving treatment, and at the time of discharge from jail or prison to the community. In a study conducted in Rhode Island, in which individuals who were receiving methadone treatment prior to incarceration were assigned to receive either continued treatment with methadone or a tapered withdrawal, individuals who received continued access to methadone while incarcerated were less likely to report using heroin and engaging in injection drug use at a 12-month follow-up after release (Brinkley-Rubinstein, McKenzie, et al., 2018). In addition, they reported fewer non-fatal overdoses and were more likely to be continuously engaged in treatment over the follow-up period compared to individuals who were not receiving methadone immediately prior to release.

In a systematic review of 21 studies reporting on illicit drug use during imprisonment (Hedrich et al., 2012), there were significant reductions in illicit opioid use, primarily heroin, associated with prison-based methadone treatment. Five of the studies that reported on drug injecting found that prison-based methadone was associated with reduced heroin injecting and sharing of injection equipment while incarcerated. Compared to baseline, risk behaviors in the methadone groups diminished substantially while they remained unchanged or increased among no OMT groups. However, findings were mixed regarding the association of MOUD and risk of re-incarceration over time.

MOUD treatment is not widely available within correctional settings given historical biases against its use and a priority on abstinence-based treatment. In a review by Taxman, Perdoni, and Caudy (2013), they estimated that existing treatment programs in the correctional system have the capacity to serve only about 10 percent of individuals who need it, and that regardless of the correctional setting, only a small portion of the offender population receives the appropriate level of treatment. Another review conducted by Belenko, Hiller, and Hamilton (2013) attributed the underutilization of MOUD in the criminal justice system to negative attitudes towards its use among corrections staff, state and local regulations, security concerns, institutional philosophy (i.e., belief in abstinence-based treatment), and lack of resources as additional barriers. Similarly, Brinkley-Rubinstein, Zaller, et al. (2018) suggest that the criminal justice system’s traditional orientation to punishment rather than public health has led to a limited number of treatment options for individuals with OUD within the correctional system.

2. Study aim and rationale

The aim of this study was to conduct a scoping review of the literature regarding implementation of MOUD within criminal justice settings and/or with justice-involved populations. A scoping review utilizes the same search procedures to identify relevant publications and/or documents as those used in systematic reviews. However, unlike systematic reviews that synthesize the evidence from studies using a common design (typically randomized controlled trials) on the effectiveness of a specific clinical or other intervention, scoping reviews do not include a quantitative synthesis of data across studies nor an assessment of the quality of the study design (Grant & Booth, 2009). Instead, a scoping review is appropriate to assess a broad range of heterogeneous studies that use different methodological approaches to address a common theme in order to delineate gaps in the extant literature and areas for future research (Tricco et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2015).

The current study is congruent with the framework for conducting scoping reviews that was initially proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005): (1) To examine the extent, range and nature of research activity in a given area; (2) To determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review; (3) To summarize and disseminate research findings; and (4) To identify research gaps in the existing literature. A scoping review was considered appropriate for the current review given the range of methodologies utilized to address the topic of implementation of MOUD, including both qualitative and quantitative studies; the diverse settings in which treatment with MOUD may be dispensed to criminal justice-involved individuals (i.e., jail, prison, community); and lack of randomized controlled trials or studies with quantifiable outcomes regarding implementation challenges, which would be more suitable to quantitative synthesis. The present scoping review was guided by the following research questions:

What are barriers to implementing MOUD within criminal justice settings or for criminal justice-involved populations?

What are facilitators of implementing MOUD within criminal justice settings or for criminal justice-involved populations?

3. Methods

3.1. Study design

The review was informed by established methods for conducting and reporting systematic reviews, as articulated in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009). Guidelines for reporting results of scoping reviews are based the original PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews that were revised using input obtained from Delphi surveys conducted with experts in the field (Tricco et al., 2018). Typically, a qualitative synthesis is used to assess the range of studies and nature of findings, and to identify common themes, areas of concurrence, and research gaps in the selected studies.

The analysis presented in this paper uses a sub-set of studies from a larger systematic review that addressed the broad topic of OUD among individuals within the criminal justice system. Thus, only the sub-set of articles that pertained specifically to implementation of MOUD within the criminal justice system (CJS) are included in the analysis for this paper, although we report the methods that were applied in the parent systematic review.

3.2. Eligibility criteria

The review was inclusive of peer-reviewed publications of studies conducted in the U.S. and other countries, although non-English papers were excluded. Given the large historical literature that exists on efforts to address opioid use disorders within criminal justice settings, which largely predates the current wave of OUD, this review was limited to articles that were published subsequent to October 2002, which is the date of FDA approval of two sublingual formulations of the Schedule III opioid partial agonist medication buprenorphine for the treatment of OUD.

Articles were excluded based on the following criteria:

Not in English

Published prior to 2002 (note: one study was excluded that was published after this cut-off, but used survey data that was collected in 1997)

Does not focus specifically on a population under legal supervision

Not published in a peer-reviewed journal

Is an opinion piece, commentary, published letter or introduction to a special issue

Is a clinical trial protocol for which more recent outcome article was obtained

Does not address topics included in the larger review (i.e., OD education and prevention; screening and assessment to identify OUD; MOUD for OUD withdrawal management; MOUD for OUD treatment; MOUD for OUD re-entry planning; or factors that support or hinder MOUD implementation)

Pertains to non-opioid MOUD (e.g., alcohol)

Focuses on law enforcement or drug control of opioids or specialty treatment courts

3.3. Search strategy

An electronic literature search of was conducted of the following databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts (NCJRS), and the Cochrane Library. A total of 10 reviewers worked on this study. To ensure consistency across reviewers, all reviewers reviewed a sub-set of 20 articles, coded them for inclusion or exclusion, discussed the results, and came to consensus on interpretation of criteria. The lead project manager then reviewed all results across reviewed and provided feedback for consistency. Two sets of search terms were used: one pertaining to medications for treatment of OUD and one pertaining to criminal justice terms. Each of the MOUD terms was searched in combination with each of the criminal justice terms for a total of 286 search term pairs searched across each of the databases identified.

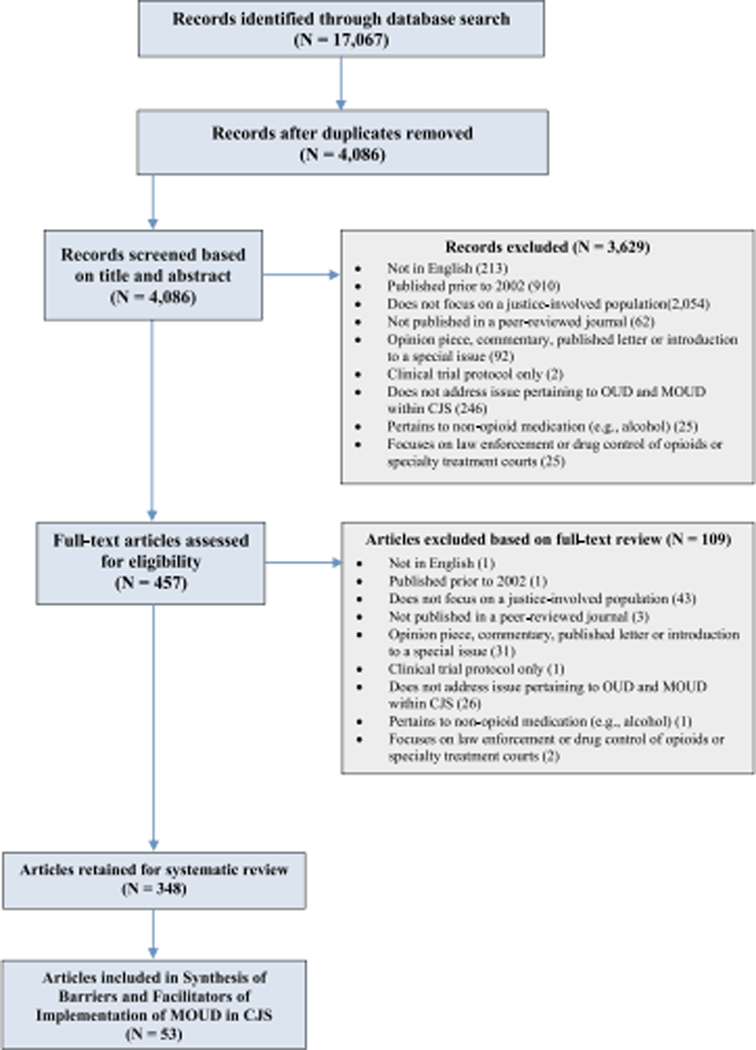

The study used a search and review process had three tiers: 1) Search results were initially screened for duplication across databases and results were unduplicated; 2) all records were then screened for inclusion based on title and abstract; and 3) full-text review based on inclusion criteria was then conducted on remaining articles. For the purposes of this paper, the sub-set of papers that were coded as relevant to “implementation of MOUD” was then selected for synthesis. See Figure 1 for the Flow Chart of the search results, based on the PRISMA criteria (Tricco et al., 2018), the PRISMA checklist in the Appendix A and sample search terms in Appendix B.

Figure 1.

Systematic Review Flow Chart

3.4. Information collected

Reviewers abstracted data on article and study characteristics and entered these into a centralized database using the following parameters; 1) study identification, e.g., author[s], year of publication, full citation; 2) study characteristics, e.g., aim, research design, setting; 3) sample characteristics, e.g., target population; 4) results; and 5) study limitations. The review was concluded on November 16, 2018 and included articles that were published online prior to in-print publication at that time.

3.5. Selection of articles included in analysis

Papers selected for this analysis addressed some aspect of implementation of MOUD either within criminal justice settings or with justice-involved populations in community settings. Inclusion was based on addressing one or more of the following issues: (1) institutional capacity or expertise to provide MOUD; (2) workforce or staffing issues related to provision of MOUD; (3) administrative policies that affect the availability or accessibility of MOUD; (4) programmatic practices, clinical interventions, or treatment orientation related to MOUD; (5) attitudes, belief, knowledge, satisfaction, or experiences with MOUD among individuals or staff in the justice system or community corrections; (6) service system relationships between the criminal justice system and community corrections, community treatment providers, or other community stakeholders (i.e., public safety) that affect the provision of MOUD; and (7) descriptions of programs or services related to MOUD that illustrate examples of implementation barriers or facilitators. Papers were excluded if they examined (without reference to any of the above): (1) use or provision of medications for overdose prevention (i.e., naloxone); (2) the outcomes of MOUD received by justice-involved individuals, i.e., relapse, recidivism, re-arrest, or death; and (3) the ethical or policy implications related to MOUD.

3.6. Analysis

The analysis for this paper uses a sub-set of 52 published papers that pertain to the topic of “implementation of MOUD within criminal justice settings or for justice-involved populations.” Published papers that originated from the same parent study, but were distinct in terms of the sub-set of data analyzed and/or the analyses that were conducted, were counted as separate papers, whereas papers that reported similar findings from one study using the same database were counted as the same study. We first summarized the nature of the included studies by location of study, type of correctional setting or population, study design, and type of MOUD addressed in the study. An inductive qualitative analysis was conducted whereby each paper was coded based on emergent themes that pertained to barriers or facilitators of MOUD implementation within the CJS. These categories were not mutually exclusive as studies may have reported on multiple types of barriers and/or facilitators. These codes were reviewed among the study team to achieve consensus.

4. Findings

4.1. Characteristics of included studies (n = 53)

Over half of the studies (n = 28) were conducted outside of the United States including: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, India, Iran, Ireland, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Moldova, Norway, Spain, Thailand, Taiwan, Ukraine, United Kingdom; 23 studies were conducted in the United States and Puerto Rico; and 2 were not specified (i.e., policy analysis)

Type of correctional setting: jail (n = 2), prison (n = 24), jail or prison (n = 9), reentry/community corrections (n = 12), other combinations of above (n = 6)

Study design: survey/structured interview (n = 20), qualitative interviews and/or focus groups (n = 19), policy analysis or program description (n = 4), quasi-experimental study or randomized controlled trial (n = 6), secondary analyses of quantitative data (n = 3), and mixed methods (quantitative/qualitative) (n = 1)

Type of MOUD: methadone (n = 21), buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone (n = 4), buprenorphine or methadone (n = 21), other combination (n = 5), not specified (n = 2)1

4.2. Classification of barriers and facilitators

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies and coding of thematic categories related to barriers and facilitators. These categories are not mutually exclusive, since one article could reference both barriers and facilitators, as well as multiple examples of each.

Table 1.

Description of Studies Included in Scoping Review on Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation of MOUD within the Criminal Justice System or with Criminal Justice Populations

| Authors/year of publication | Corrections type | Medication type | Study design | Study population/ setting | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Albizu-Garcia, Caraballo, 2012 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine/naloxone | Survey | 1,331 randomly-selected, sentenced inmates from 26 of 39 penal institutions in Puerto Rico |

Institutional: Limited capacity for in-prison MAT Systemic: Limited capacity for transition to community MAT upon release |

|

| 2. Andraka-Christou, Capone, 2018 | Probation, Parole | Buprenorphine, Extended release naltrexone | Qualitative interviews | 20 physicians sampled at medical conferences and by referral in Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, U.S. |

Systemic: CJ system requirements were cited as barriers, e.g., many CJ reporting requirements, often without reimbursement; CJ administrators discouraged use of bup injections; concern that patient health information, such as urine test results, could be used punitively. |

|

| 3. Aronowitz, Laurent, 2016 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Qualitative: semi-structured in-depth interviews |

10 current and former patients at an outpatient treatment center who had been previously incarcerated; New England, U.S. | Programmatic: Traumatic taper experiences while incarcerated, suboptimal medical care, feeling “trapped and helpless,” and access to substances in prison leads to relapse upon release | |

| 4. Awgu, Magura, 2010 | Jail | Methadone, Buprenorphine | RCT | 114 inmates screened for OUD at jail entry were randomly assigned to methadone or buprenorphine MAT at the Rikers Island Jail complex, New York City, U.S. |

Programmatic: Average methadone dose was lower than recommended levels whereas average bup dose was at recommended levels. Attitudinal: Methadone participants were more likely to report side effects and withdrawal effects, greater discomfort during the first days of treatment, perceptions of stigma from others and to be concerned about developing dependency |

Attitudinal: Bup patients were significantly more likely (93% vs. 44%) to report intentions to enroll in community treatment post-release |

| 5. Azbel, Rosanova, 2017 | Prison | Methadone | Qualitative: focus groups, interviews |

110 individuals with OUD enrolled in a prison-based abstinence-oriented TC; 20 TC staff members; and 2 former participants in 4 prisons in Kyrgyzstan |

Attitudinal: Both participants and staff report “extremely” negative beliefs about MMT; participants in TC “fear” methadone and feel morally superior because they are “clean” |

|

| 6. Bachireddy, Bazazi, 2011 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Qualitative interviews | 102 HIV+ infected male offenders, 95% with OUD, who were within six months of community re-entry in Malaysia |

Attitudinal: 51% believed that OST “would be helpful” and 54% of these felt it would prevent relapse after reentry; 70% of sample was interested in learning more about the service; among those with prior OST there were high levels of satisfaction and 93% said they would refer friends to services if they were available. |

|

| 7. Carlin, 2005 | Prison | Methadone | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews, focus group |

Prisoners (n=15) and prison staff (n = 16) and a focus group with 8 prisoners in Dublin, Ireland |

Programmatic: Operational difficulties in dispensing methadone in a prison setting; therapeutic intent of the methadone program “fitted uneasily into the custodial milieu” |

Programmatic: Reduces the supply of heroin in prison; helps control prisoners and maintain order and discipline; prevents needle sharing and the spread of blood-borne infections; treats heroin addiction; Systemic: Continuity of harm-reduction policies from the community |

| 8. Chavez, 2012 | Prison, Jail | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Policy analysis | N/A |

Institutional: Limited capacity |

Institutional: Expanding access to MAT in prison improves individual and public health Programmatic: Correctional nurses can play a key role in expanding MAT in correctional settings |

| 9. Fox, Maradiaga, 2015 | Re-entry | Buprenorphine | Qualitative interviews | 21 formerly incarcerated men and women with OUD in New York, U.S. |

Attitudinal: Persistent exposure to drug use and stressful life events contribute to opioid relapse and affected treatment decisions during re-entry. Themes: 1) reliance on willpower is more important than medication treatment; 2) fear of dependency on medications from prior painful methadone withdrawal; 3) variable exposure to bup (both positive and negative) prior to incarceration |

Attitudinal: Bup was perceived as a good treatment option for OUD that could reduce the risk of re-incarceration and was considered to be acceptable following relapse Programmatic: Both policy changes and interventions to improve education and access to bup for former inmates are needed to reduce the negative consequences of opioid relapse following re-entry |

| 10. Friedmann & Hoskinson, Gordon, et al., 2012 | Jail, prison, parole, probation | Methadone, Buprenorphine, Naltrexone, Clonidine |

Survey | Convenience sample of 50 CJ agencies in CJ-DATS, including: 18 jails, 12 prison or unified prison/jail systems, 12 probation or parole or unified probation/parole departments, and 8 drug courts; located in 16 different states and territories in the U.S. (CJ-DATS) |

Institutional: Restrictive policies, i.e., pregnant women, individuals who are HIV+ or in withdrawal were most likely to receive MAT in jail or prison; unlikely to receive MAT at re-entry; security concerns, regulations prohibiting use of MAT for certain agencies; lack of qualified medical staff Attitudinal: Preferences for drug-free treatment (especially in prisons); limited knowledge of the benefits of MAT Systemic: Better linkages to community MAT during re-entry period is needed to address barriers re: security, liability, staffing, and regulatory concerns |

|

| 11. Friedmann, Wilson, 2015 | Probation, Parole, Community treatment | Methadone, Buprenorphine, Naltrexone | Cluster randomized trial of: (1) training on knowledge, perceptions, and referral information, and (2) a 12-month organizational linkage intervention on interagency strategic planning and implementation | 20 clusters (N = 847 pre/post survey respondents) consisted of community corrections staff (e.g., probation, parole, prison, TASC) and their offender caseloads nested within agencies, each of which was partnered with at least one community-based SUD treatment program, in U.S. (CJ-DATS MATTICE Study) |

Programmatic: Training increased familiarity and knowledge of MOUD and referral sources in both groups; compared to training only, the experimental intervention produced more improvements in functional attitudes and intent to refer clients to methadone and oral naltrexone and future intention to refer to bup among both correctional and treatment staff, although correctional staff had greater reductions in negative perceptions of MOUD than treatment staff; corrections staff in experimental sites had greater intent to refer clients to methadone, bup, and XR-NTX than controls |

|

| 12. Fu, Zaller, 2013 | Jail, Prison | Methadone | Survey | 215 individuals with OUD at two inpatient medication-assisted detox facilities in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, U.S. |

Programmatic/Systemic: Forced detox while incarcerated is a deterrent to engaging in MMT in community |

|

| 13. Havnes, Clausen, 2014 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine |

Qualitative interviews | 9 men and 3 women who were on MMT while incarcerated in Norway |

Attitudinal: Focus on agency of incarcerated individuals, e.g., self-control, self-regulation, & motivation as instrumental in successful treatment with MMT within the context of “ceaseless surveillance” in prison |

|

| 14. Hayashi, Lianping, 2017 | Prison re-entry | Methadone |

Mixed methods: Quantitative descriptive analysis; Qualitative interviews |

Quantitative: 158 injection drug users (some with history of incarceration) in MMT; Qualitative: 12 participants; Bangkok, Thailand |

Systemic: Lack of MMT in prisons was a major reason for methadone discontinuation in community; police harassment around clinics |

|

| 15. Jhanjee, Pant, 2015 | Prison, Jail | Buprenorphine | Qualitative analysis | Methadone treatment program in Tihar prison complex in India |

Institutional: Challenge to maintain a trained workforce Programmatic: Attrition from treatment stemming from involvement in criminal activities; limited time available for treatment; 3 months to establish MAT program in prison |

|

| 16. Kinlock, Gordon, 2013 | Prison reentry | Methadone | Secondary analysis of data from a RCT |

67 male prerelease prison inmates with OUD in Baltimore, MD |

Attitudinal: Negative view of effectiveness of MMT among those who discontinued MMT in prison |

|

| 17. Kinner, Moore, 2013 | Prison | Methadone | Secondary analysis of combined data from (1) prior health survey and (2) RCT | 1,128 prisoners in New South Wales and Queensland, Australia |

Programmatic: In-prison OST may reduce injection activity; possible sex difference |

|

| 18. Kouyoumdjian, Patel, 2018 | Prison, Jail | Buprenorphine, Methadone, Naloxone |

Online survey | 27 physicians from correctional facilities in Ontario, Canada |

Programmatic: About half of physicians surveyed prescribed methadone and bup/ naloxone and a minority had initiated patients on OAT while in custody; physicians reported concerns about medication diversion and safety & initiating OAT for prisoners who are not using opioids Systemic: Lack of linkage with community-based providers and the government Ministry |

Institutional: Support from institutional health care staff and administrative staff, adequate resources for program delivery |

| 19. Larney, Zador, 2017 | Prison | Methadone | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | 46 prisoners - 27 in OST in Australia |

Attitudinal: One-third of the participants stated intentions to leave OST prior to release due to fears that community OST could lead to drug use and other complications |

|

| 20. Maradiaga, Nahvi, 2016 | Prison re-entry | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews |

21 formerly incarcerated individuals with OUD recruited from a federally qualified health center and a community-based SUD treatment provider (non-pharmacologic) to formerly incarcerated individuals in state prisons in New York, U.S. |

Programmatic: Post-release aversion to MMT from rapid dose reduction and discontinuity of MMT during incarceration Systemic: Inadequate access while incarcerated is a barrier to treatment post-release |

|

| 21. Marco, Gallego, 2013 | Jail, Prison | Methadone | Cross-sectional survey | 158 male inmates with OUD in MMT in prison in Spain | Attitudinal: Dissatisfaction with MMT associated with number of prior MMT episodes |

Attitudinal Satisfaction with MMT associated with HIV+ status and patient perceived influence on dose changes |

| 22. Matejkowski, Dugosh, 2015 | Prison, Probation, Drug court | Methadone, Buprenorphine, Naltrexone | Quasi-experimental: pre/post assessment of attitudes re: MAT after online training intervention | CJ system treatment referrers (n = 45) and decision-makers (n = 25) at a private provider of in-prison treatment, nonprofit provider of case management services for prisoners, county probation agency and drug treatment court in Northeast, U.S. |

Institutional: Significant increases in knowledge, attitudes toward MAT, and willingness to refer to MAT following online training among treatment referrers and decision-makers |

|

| 23. Mazhnaya, Bojko, 2016 | Jail, Probation, Parole | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Qualitative: focus groups |

25 focus groups with 199 individuals with OUD sampled from OAT treatment programs in Donetsk, L’viv, Odesa, Mykolaiv, Kyiv - Ukraine |

Attitudinal/Systemic: Prisoners view themselves as “addiction free” when in prison and avoid OST after release as they are “targets” for police harassment; cycle of relapse, re-arrest, re-incarceration |

Attitudinal: Fear of police and arrest may facilitate OST entry |

| 24. McKenzie, Nunn, Zaller, Rich, 2009 | Prison | Methadone | Policy analysis | Correctional system in Rhode Island, U.S. |

Institutional: Challenges to initiating MMT stemming from staff obstacles; preference for abstinence-only approaches in CJS |

|

| 25. Michel, Carrieri, 2008 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine |

Qualitative interviews | Prisoners in France |

Attitudinal: Physician resistance to methadone treatment |

|

| 26. Mitchell, Kelly, 2009 | Prison re-entry | Methadone | Qualitative: ethnographic interviews | 53 individuals with OUD: 23 in treatment, 21 not in treatment in Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

Attitudinal: Negative methadone withdrawal experience influenced participants’ attitudes about MMT at release |

|

| 27. Mitchell, Willet, 2016 | Community corrections | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews |

111 probation/ parole officers in 9 states in U.S. (CJ-DATS MATTICE Study) |

Attitudinal: Community corrections agents concerned about “abuse potential”; “unsupportive” of long-term MAT; viewed MAT as “treatment of last resort” |

Attitudinal: Favorability enhanced with successful experiences of patients on MAT |

| 28. Mjaland, 2015 | Prison | Buprenorphine | Qualitative: participant observation and interviews | Prisoners (n = 23) and prison staff (n = 12) in the drug treatment unit and OMT unit in Norway |

Programmatic: Efforts to reduce diversion of bup led to “excessive and repressive control” that was perceived as illegitimate and unfair by prisoners; prisoners resisted the perceived unfairness of repressive practices through diversion of bup |

|

| 29. Monico, Mitchell, 2016 | Community corrections | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Qualitative interviews pre-and post implementation of training/inter-organizational intervention | 118 probation and parole officers (PPO) and 23 treatment program staff participating in RCT in 9 states in U.S. (CJ-DATS MATTICE Study) |

Systemic: Problems in communication between PPOs and treatment staff stemmed from negative perceptions of the other agency, often based on limited interactions and use of indirect channels of communication (i.e., third party), leading to weak working relationships; lack of adequate monitoring information from treatment staff hindered PPO’s ability to accurately assess adherence; conflict between therapeutic and correctional goals |

Systemic: Regular communication and an understanding of respective processes facilitated effective working relationships; both PPOs and treatment staff agree that direct communication between the agencies is needed for information exchange and as a tool for collaboration to achieve their respective missions |

| 30. Moradi, Farnia, 2015 | Prison | Methadone | Qualitative: focus groups |

7 focus groups with physicians, consultants, experts; 7 focus groups with directors and managers of prisons (total N = 140) in Iran |

Institutional: Lack of skilled workforce Programmatic: Inaccurate implementation of clinical protocols Systemic: Poor care after release from prison |

Programmatic: Reduction of illegal drug use and high-risk injection and other behaviors leads to more positive attitudes |

| 31. Mukherjee, Wickersham, 2016 | Prison | Methadone | Structured interview | 96 HIV+ and 104 HIV- incarcerated men who met pre-incarceration criteria for OUD in Malaysia |

Attitudinal: Less than half of sample would be willing to enroll in MMT despite meeting criteria for treatment; “cognitive dissonance” between risk of opioid relapse and re-incarceration |

Attitudinal: Prisoners who had greater severity, i.e., daily use and had experienced more negative consequences related to drug use, were more interested in initiating MMT |

| 32. Nunn, Zaller, 2009, 2010, 2011 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Survey | Medical directors from 50 state prisons plus DC and Federal Department of Corrections, U.S. |

Institutional: 55% (n=28) of state prison systems provide methadone in some situations; varies widely across states; over half that so offer methadone limit its use to pregnant women or chronic pain management; 14% (n=7) offer bup to some inmates Programmatic: Preference for drug-free detox Systemic: Post-release referrals: 45% provide referrals to MMT programs and 29% provide referrals to bup providers |

|

| 33. Oser, Knudsen, 2009 | Jail, Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine, LAAM, Naltrexone, |

Survey | Nationally representative sample of 198 correctional institutions, U.S. |

Institutional: Limited capacity: 34% of jails and 5% of prisons offered detox services; 32% of jails and 6% of prisons provided pharmacotherapy for SUD; jails were 8 times more likely to offer detox and 4 times more likely to offer pharmacotherapy for SUD |

Institutional: Institutions that provided mental health counseling or medications for SUD were more likely to provide detox services and medications for SUD treatment; positive relationship between the Traditional CJ Goals Scale and the availability of medication-based treatments |

| 34. Polonsky, Azbel, 2015 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Survey | 243 administrative, medical, and custodial prison staff in Ukraine |

Attitudinal: Prison staff have “ideological biases and negative attitudes” toward MMT, addiction, and individuals with HIV |

Attitudinal: More knowledge about OAT was associated with more favorable attitudes |

| 35. Polonsky, Azbel, 2016 | Prison | Methadone | Survey | 56 individuals with OUD who were recently released from prison in Moldova |

Attitudinal: Knowledge, myths and “prejudice” toward OAT may co-exist |

Attitudinal: More knowledge about OAT was associated with more favorable attitudes |

| 36. Polonsky, Rozanova, 2016 | Prison re-entry | Methadone | Survey | 196 individuals with OUD who: (1) were HIV+ and within 6 months of release from prison; (2) had been recently released from prison and were sampled at sites providing post-release assistance in Ukraine |

Attitudinal: MMT and recovery viewed as mutually exclusive; individuals express more optimism about changing their drug use and intentions to recover prior to release from prison |

|

| 37. Radcliffe, Stevens, 2008 | Community treatment | Methadone | Qualitative interviews | 53 former clients from 12 randomly selected SUD treatment providers, who had left treatment prior to discharge in England |

Attitudinal: Stigma associated with drug use and treatment; desire for “normal” life |

|

| 38. Rich, Boutwell, 2005 | Prison | Methadone | Survey (mailed) | 40 (out of 51) medical directors of state and federal prisons in U.S. |

Institutional: 19 respondents indicated their institution provided methadone detox or maintenance; MMT was only available to pregnant women with OUD (n=13); logistical obstacles and security concerns were most often cited barriers; only 3 respondents referred individuals to MMT at release |

|

| 39. Rozanova, Morozova, 2018 | Re-entry | Methadone | Survey | Prisoners (n = 577) with OUD who were within 6 months of release in Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan |

Attitudinal: Individuals prioritized finding employment, reconnecting with family, and staying out of prison over treatment for OUD, general health conditions, and initiating methadone treatment |

Attitudinal: Individuals with prior drug injection and treatment with methadone treatment had more interest in methadone in all countries; participants with poorer general health were more likely to prioritize SUD treatment |

| 40. Schulte, Stöver, 2009 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Survey | Physicians from prisons in Germany |

Institutional: Need for more physicians skilled in addiction medicine Programmatic: Strong abstinence-orientation and time-limited criteria leading to short and limited treatment durations (non-maintenance) |

|

| 41. Springer, Bruce, 2008 | Jail, Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Survey | 27 correctional staff who work with inmates in patient care or case management in Connecticut, U.S. |

Institutional: Correctional workers lacked knowledge about methadone and bup effects on health and HIV risk Systemic: Correctional workers do not refer released prisoners with OUD to MAT in community |

|

| 42. Streisel, 2018 | Jail, Probation, Parole | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Survey of staff in programs participating in a cluster randomized trial | 959 community corrections workers (treatment specialists and officers) sampled from 20 community corrections agencies in 9 states in U.S. (CJ-DATS MATICCE Study) |

Programmatic: Preferential referral patterns to either methadone or bup were influenced by work setting, level of education, training Attitudinal: MAT was negatively perceived as a substitute addiction |

|

| 43. Trigg, Dickman, 2012 | Prison, Jail | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Program description | Public health, state and local government, corrections, academia, and community agencies in New Mexico, U.S. |

Systemic: Cross-system collaborations promote increased capacity and access to MAT in jails, which has public health benefits |

|

| 44. Turban, 2012 | Prison re-entry | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Quasi-experimental: assessment of attitudes and perceptions regarding MAT pre/post intervention | 37 state parole officers, Federal pre-detention officers and parole officers in U.S. |

Programmatic: Informational intervention reduced misperceptions and increased acceptability of MAT among parole officers |

|

| 45. Victorri-Vigneau, Rousselet, 2016 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Quasi-experimental: survey pre/post intervention | Physicians in 3 settings, including specialized centers for patients with OUD in prison in France |

Programmatic: Urine test strips were effective in assisting physicians in managing changes in medication during consult for renewal and enable physicians to “optimize therapeutic strategy” |

|

| 46. Wakeman, Rich, 2015; Wakeman, 2017 | Prison | N/A | Policy analysis | N/A |

Programmatic: “Antipathy” among correctional staff regarding OAT leads to unethical withholding of treatment Attitudinal: Stigma associated with MOUD |

|

| 47. Welsh, Knudsen, 2015 | Community corrections, community treatment | Methadone, Buprenorphine, Naltrexone |

Mixed methods: (1) quantitative surveys of participants in cluster RCT, and (2) qualitative interviews | (1) Surveys with 429 parole/ probation officers and 270 treatment providers; (2) 207 interview transcripts; sampled from 20 sites in the U.S. (CJ-DATS MATTICE Study) |

Programmatic/Systemic: Differences in organizational structure and culture and professional role perceptions across community corrections and treatment underlie differing perceptions of inter-organizational relationships |

Programmatic/Systemic: Experimental group improved more on measures of Agency and Personal Awareness and Frequency of Communication; treatment staff reported greater improvements in inter-organizational relationships than corrections staff; encourage slower, more realistic pace of change |

| 48. Wickersham, Marcus, 2013 | Prison re-entry | Methadone | Qualitative: interviews with prisoners prior to and after release; focus groups with prisoners; unstructured discussions with physicians |

72 HIV+ male prisoners who were enrolled in a pilot MMT program in Malaysia |

Programmatic: Initiation of MMT requires slow, individualized dosing which is hampered by institutional setting; lack of training of primary care physicians and preference for “low” dosing Systemic: Continuity of care following release is hampered by: 1) patient supervision is outside the prison system; 2) police harassment near MMT sites and forced relocation laws; 3) differences in clinical approaches, whereby community treatment providers reduce doses that are considered “too high”; 4) problems in reuniting the patient with family due to stigma and hostility |

Institutional: Provision of ongoing feedback and discussion with prison administrators to increase their understanding and confidence in the pilot program Programmatic: Ongoing educational training of physicians and patients to improve medication induction so as to be individualized to address each patient’s symptoms and other health problems. Systemic: Linking individuals to MMT in community requires strong relationships between prison- and community-based clinics and improved communication between prison and police authorities |

| 49. Wright, French, 2014 | Prison | Methadone | Secondary analysis of time series data | Administrative data on prescribing of methadone detoxification and maintenance therapies, and opiate-related deaths over 7 years from prison in U.K. |

Programmatic: Phased implementation of general practitioner specialist in SUD led to increase in MMT and detoxification treatments; over time the rate of MMT plateaued with a corresponding decrease in the rate of methadone detox |

|

| 50. Wright, Mohammed, 2014; Mohammed, Hughes, 2016 | Prison | Buprenorphine, Naloxone | Cross-sectional survey | 85 male prisoners in U.K |

Programmatic: Prisoners estimate a higher cost of bup than bup/naloxone both inside and outside prison, leading to more bup diversion; recommend use of bup/naloxone to reduce abuse potential |

|

| 51. Yen, Tsai, 2011 | Jail | Methadone | Survey | 315 intravenous heroin users recruited from four jails in Taiwan |

Attitudinal: Young heroin users with no prior MMT perceive more benefits to heroin use and have negative attitudes about MMT on the Client Attitudes Toward Methadone Programs Scale |

|

| 52. Zamani, Farnia, 2010 | Prison | Methadone | Qualitative field observations, focus group discussions, and individual interviews | 30 prisoners and 15 prison staff and health policymakers in Iran |

Attitudinal: Favorable perceptions of MMT stemming from health benefits to inmates and positive effects on socio-economic status of prisoners’ families |

Institutional: Staff shortages, methadone diversion Programmatic: Concerns over the possible side effects of methadone Attitudinal: Stigma attached to methadone treatment. |

| 53. Zurhold, Stöver, 2016 | Prison | Methadone, Buprenorphine | Semi-structured survey | National institutions responsible for prison services in 27 European countries |

Institutional: Access to OST in prisons is higher in countries with established history of OST provision in community, and is less accessible in countries that introduced OST more recently |

Abbreviations:

Bup = buprenorphine; CJ = criminal justice; CJ-DATS = Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies; MAT = medication assisted treatment; MMT = methadone maintenance treatment; MOUD = medication for opioid use disorder; OAT = opiate agonist treatment; OST = opiate substitution treatment; OUD = opioid use disorder; SUD = substance use disorder; TC = therapeutic community; XR-NTX = extended release naltrexone

Four categories of barriers/facilitators to MOUD implementation were identified:

Institutional factors refer to characteristics of the institution (i.e., prion, jail, community corrections), such as capacity, workforce, and institutional policies or regulations.

Programmatic factors are defined as operations, practices, or interventions that are reflective of or implemented within a program within the institution, most often clinical or treatment programs

Attitudes refer to attitudes, knowledge, beliefs, and other attributes of individuals (e.g., motivation), which are further categorized into those pertaining to justice-involved individuals and to CJS staff and stakeholders

Systemic factors pertain to relationships or interactions between the CJS nd external service providers or service systems.

4.3. Institutional barriers

A total of 11 studies identified institutional barriers to delivery of MOUD in criminal justice settings or to criminal justice populations. Institutional barriers stemmed from limited capacity, lack of qualified workforce, and policies restricting treatment with MOUD to specific sub-groups.

In an extensive survey of 50 U.S. prisons, (Nunn & Zaller, 2009, 2010) found that 28 prison systems (55%) offered methadone treatment to inmates, but over half of these restricted its use (e.g., limited to pregnant women or for chronic pain management). At the time of this survey, 7 state prison systems (14%) offered buprenorphine to some inmates. A survey using a stratified random sample of sentenced inmates from the Puerto Rican prison system in 2004 yielded a sample representing 13% of the total sentenced inmate population. The authors estimated that the current treatment capacity in Puerto Rico was sufficient to treat less than 15% of inmates assessed with OUD, and was further limited to males only (Albizu-Garcia, Caraballo, Caraballo, & Hernández-Viver, 2012).

In a survey of a nationally representative sample of 198 prisons and jails in the U.S., conducted as part of the NIDA-sponsored cooperative agreement, the Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies (CJ-DATS), capacity for detoxification and pharmacotherapies for SUD treatment was limited. Detoxification services were offered by 5% of prisons and 34% of jails whereas pharmacotherapies for SUD treatment was provided by 6% of prisons and 32% of jails (Oser, Knudsen, Staton-Tindall, Taxman, & Leuefeld, 2009). In multivariate models controlling for organizational characteristics, odds ratios for the provision of detox services and pharmacotherapies for SUD treatment in jail versus prison were 7.7 and 3.7, respectively.

Lack of physicians qualified in addiction medicine was cited as a capacity barrier in a survey of 50 correctional agencies in the U.S. (Friedmann et al., 2012) and in a survey of 31 prisons in Germany (Schulte & Stover, 2009). Workforce capacity was also cited as a barrier to implementation of treatment with MOUD in a qualitative study using focus groups with physicians, consultants, experts, directors, and managers of a prison complex in Delhi, India (Jhanjee et al., 2015) as well as in focus groups with prison personnel in Iran (Moradi et al., 2015).

Institutional barriers also stemmed from restrictive policies regarding the delivery of MOUD, which typically limited its use to certain groups, such as for pregnant women or chronic pain patients (Nunn & Zaller, 2009, 2010). A survey conducted by mail of medical directors of state and federal prisons in the U.S. (n = 40) regarding the provision of methadone found that less than half (n = 19) of respondents reported their institution provided methadone detoxification or maintenance services; further, in most cases methadone maintenance was provided only to opioid-dependent pregnant women (Rich & McKenzie, 2015). Respondents most often cited logistical obstacles and security concerns as barriers, and only three reported referring inmates to methadone treatment services on release. A later and more comprehensive survey of 50 correctional agencies in the U.S. (representing a range of intercept points within the system) found that provision of MOUD was most often limited to treatment of pregnant women, individuals in withdrawal, and HIV+ individuals (Friedmann et al., 2012).

4.4. Programmatic barriers

4.4.1. Forced detox/lack of appropriate clinical protocols

Five studies identified the failure to use appropriate clinical protocols for OUD withdrawal management, forced or involuntary detox, and lower than recommended methadone dosing as deterrents to MOUD implementation within correctional settings. The lack of adequate withdrawal management or use of standard dosing protocols is likely rooted in the primary abstinence-orientation of the CJS and associated stigma regarding opioid addiction, leading to an aversion to use of MOUD to treat OUD. These stigmatized beliefs in turn undergird sub-optimal clinical practices and become a form of “enacted stigma” (Tsai et al., 2019) among corrections-based treatment providers that hinders its implementation.

Having been involuntarily tapered from a MOUD while in jail or prison was viewed by individuals as highly traumatic and created a disincentive to engaging in treatment with MOUD in the community after release. This factor was cited in a qualitative study of previously incarcerated patients in a New England state (Aronowitz & Laurent, 2016); in a survey of 215 individuals with OUD at two inpatient medication-assisted detox facilities in Rhode Island and Massachusetts (Fu, Zaller, Yokell, Bazazi, & Rich, 2013); and in a qualitative study of 21 formerly incarcerated individuals with OUD recruited from a federally qualified health center and a community-based SUD treatment provider (non-pharmacologic) to individuals who had formerly been incarcerated in state prisons in New York (Maradiaga & Nahvi, 2016). Moreover, poor implementation of clinical protocols for MOUD was cited as a barrier by physicians and administrators of prisons in Iran (Moradi et al., 2015); and lower than recommended doses of methadone among jail inmates in New York were associated with more negative treatment experiences while incarcerated (Awgu & Magura, 2010).

4.4.2. Abstinence orientation/correctional environment

A preference for abstinence-oriented treatment was pervasive in correctional settings, and was cited as a barrier to MOUD implementation in nine studies. In a survey of prison-based physicians in Germany, the strong abstinence-orientation within prison settings characterized the approach to treatment with MOUD as time-limited and restricted to detoxification, rather than for maintenance treatment (Schulte & Stover, 2009). This perspective was echoed in a qualitative study conducted in Dublin, Ireland that conducted semi-structured interviews with prisoners (n = 15) and prison staff (n = 16) and a focus group with 8 prisoners (Carlin, 2005). Participants cited the “operational difficulties” in integrating methadone treatment in a prison, and described how the therapeutic approach of treatment with MOUD “fitted uneasily into the custodial milieu.” The therapeutic goals of methadone treatment were also hampered by the limited time duration available for maintenance treatment induction in a prison complex in India (Jhanjee et al., 2015) and in a qualitative study of prisoners and physicians in Malaysia that cited the need for “slow, individualized dosing” (Wickersham & Marcus, 2013).

A survey of 27 physicians in correctional programs in Ontario, Canada identified multiple barriers that reflected the lack of programmatic support and resources for use of MOUD in prisons. These included concerns about initiating treatment with MOUD (especially regarding buprenorphine) among prisoners who were currently abstinent from opioids, as well as physicians’ lack of qualifications, time, knowledge, and interest; lack of institutional support, resources, and nursing staff; and lack of linkages to MOUD providers in the community and poor patient adherence upon release (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2018). In open-ended comments, several physicians in this survey expressed their preference for “weaning” individuals off of treatment with MOUD while in custody and doubted its effectiveness over abstinence-based approaches, including counseling and relapse prevention.

Challenges to implementing MOUD treatment in prison were attributed to the preference for “drug-free” detox in a survey of prison administrations in the U.S. (Nunn & Zaller, 2009, 2010; Nunn et al., 2011), to staff resistance in a state correctional system (McKenzie, Nunn, Zaller, Bazazi, & Rich, 2009), and poor adherence to clinical guidelines in Iran (Moradi et al., 2015). “Biases” among community corrections staff was cited as a barrier to referring individuals to particular types of MOUD treatment within the community, and these preferences were associated with work setting, level of education, and training (Streisel, 2018).

4.4.3. Concerns about diversion

Three studies addressed institutional barriers to implementation of MOUD that stemmed from concerns about diversion within correctional settings. An online survey of 27 physicians in Ontario regarding treatment with MOUD in provincial correctional facilities found that concerns about medication diversion (either methadone or buprenorphine) was the most frequently cited barrier out of a list of 13 (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2018). Similarly, focus groups and interviews conducted with 15 staff at one prison in Iran identified concerns about diversion as an impediment to methadone maintenance in prison (Zamani et al., 2010). An in-depth ethnographic study of the implementation of a prison-based MOUD treatment program in Norway included eight months of participant observation in the prison as well as qualitative interviews with 23 prisoners and 12 prison staff. The authors describe how concerns about diversion led to the use of “strict and repressive control” to prevent the diversion of buprenorphine (Mjaland, 2015); however, the diversion of buprenorphine increased rather than decreased after the establishment of the treatment unit. The authors analyze this paradox using theories of legitimacy, power and resistance, and argue that the “excessive and repressive control” was perceived as illegitimate and unfair by the majority of prisoners in the study. The increase in buprenorphine diversion was interpreted as a form of collective resistance towards the perceived unfairness of the security measures that characterized the MOUD treatment program.

4.5. Attitudinal barriers

The largest number of studies (n = 19) identified negative attitudes toward MOUD as a barrier to treatment among either among justice-involved individuals or staff who work in correctional or community settings with this population. Moreover, stigma associated with MOUD is pervasive within society and reflected within the criminal justice system among prisoners and staff (Wakeman, 2017).

4.5.1. Negative attitudes toward MOUD among justice-involved individuals

Negative attitudes toward MOUD among justice-involved individuals were commonly reported in studies conducted across a range of community and correctional settings. In many cases, these negative attitudes were a byproduct of prior experiences of involuntary or poorly managed withdrawal in jail or prison. In other cases, negative attitudes toward MOUD reflected a priority on “abstinence” and a belief that use of MOUD was in contradiction to be being “in recovery.”

Beliefs about drug use and treatment, including use of MOUD, influenced intentions or motivation to engage in treatment with MOUD following release to the community among those who were awaiting release or newly released. In a study using semi-structured interviews with 46 prisoners in Australia, one-third stated their intentions to leave maintenance treatment prior to their release due to fears that community treatment could lead to drug use and other complications (Larney, Zador, Sindicich, & Dolan, 2017). In a survey of 196 HIV+ individuals with OUD, who were within 6 months of release or had been recently released from prisons in Ukraine, Azerbaijan, or Kyrgyzstan, many viewed methadone maintenance treatment and recovery as contradictory. Individuals who were still incarcerated expressed more optimism about changing their drug use and intentions to recover prior to their release (Polonsky & Rozanova, 2016). Instead, prisoners with OUD who were within 6 months of release prioritized finding employment, reconnecting with family, and staying out of prison over OUD treatment (Rozanova et al., 2018). Similarly, among a sample of male prisoners with OUD in Malaysia, half of whom were HIV+, fewer than half stated their intentions to seek methadone maintenance treatment after their release; the authors interpreted their resistance to a lack of realization of the high risks of relapse and reincarceration (Mukherjee & Wickersham, 2016).

In a randomized controlled trial, conducted at Rikers Island prison in New York City, inmates who were randomly assigned to treatment with methadone had more negative attitudes and less satisfaction with treatment compared to those who received buprenorphine (Awgu & Magura, 2010). Further, their negative experiences with methadone, which included more side effects and symptoms of withdrawal during induction, and perceived stigma from others, were associated with more concerns about developing dependence and lower intentions to enroll in community-based methadone treatment following release. Moreover, the authors attributed the more negative experiences among those on methadone to the dosing that was below recommended levels, which was not the case among those who received buprenorphine.

Several studies underscored the stigma attached to use of MOUD as a barrier to treatment. In qualitative interviews conducted with 53 former clients from SUD treatment providers, who had left treatment prior to their discharge from prison in England, drug use and treatment were highly stigmatized, and contradicted their desire for a “normal” life (Radcliffe & Stevens, 2008). In a study that conducted focus groups and qualitative interviews, both participants and staff in a prison-based therapeutic community (TC) in Kyrgyzstan reported “extremely negative attitudes” towards methadone maintenance treatment as well as those enrolled in it (Azbel & Rosanova, 2017). Reflecting the abstinence orientation of the TC, participants reported feeling morally superior towards those who received methadone treatment, and both participants and staff considered those who were enrolled in methadone treatment not to be “clean” of substance use.

Prior experiences with methadone treatment also influenced attitudes toward engaging in treatment following release. In a study conducting qualitative interviews with 53 individuals with OUD in the U.S., about half of whom were currently in treatment, prior negative methadone withdrawal experiences influenced their receptivity to methadone treatment at release (Mitchell et al., 2009). In one study with 21 formerly incarcerated men and women in New York who were recruited from community treatment programs, both positive and negative attitudes were expressed about buprenorphine maintenance treatment, although negative attitudes predominated (Fox et al., 2015). Participants felt that willpower was more important for recovery than use of medications. Those who had been on methadone maintenance treatment at the time they were incarcerated had all undergone rapid and painful detoxification, often experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms for months. The predominant attitude was a fear of future dependency that would lead to another painful withdrawal again in the future.

Similarly, in a secondary analysis of data from 67 male prerelease prison inmates with preincarceration heroin addiction in Baltimore, participants who had discontinued methadone maintenance treatment in prison expressed ambivalence or negative views of the effectiveness of methadone treatment (Kinlock & Gordon, 2013). A cross-sectional survey with 158 male inmates with OUD in methadone maintenance treatment in prison in Spain found that more dissatisfaction with methadone treatment was associated with more prior methadone treatment episodes (Marco et al., 2013). In contrast, one study with 315 intravenous heroin users who were recruited from four jails in Taiwan found that individuals who were younger, had started using heroin earlier, and had never participated in methadone treatment perceived many advantages and few disadvantages of heroin use, although this was also associated with symptoms of depression (Yen & Tsai, 2011).

4.5.2. Negative attitudes toward MOUD among staff in CJS

Similar to the findings of negative attitudes toward treatment with MOUD among justice-involved individuals, staff and key stakeholders in the correctional system often hold negative attitudes regarding MOUD and maintain a preference for abstinence-based treatment. This was the case in two studies conducted in Kyrgyzstan, among treatment staff in a prison-based TC (Azbel & Rosanova, 2017), and among prison staff, who have “ideological biases and negative attitudes” toward methadone maintenance treatment, as well as about individuals that use drugs and/or are HIV+ (Polonsky & Azbel, 2015). A study of physicians in prisons in France also documented “resistance” to use of treatment with MOUD (Michel & Carrieri, 2008).

Four studies conducted in the U.S. found a lack of knowledge about MOUD and negative attitudes toward its use in: (1) a comprehensive survey of staff across the correctional system (jail, prison, parole, probation) who expressed a preference for drug-free treatment and a lack of knowledge of the benefits of treatment with MOUD (Friedmann et al., 2012); (2) a study of probation and parole officers in the U.S., who viewed methadone maintenance treatment as the “treatment of last resort” (Mitchell et al., 2016); (3) a survey of 27 correctional staff who work directly with inmates in patient care or case management in one state system (Springer & Bruce, 2008); and (4) a survey of staff in 20 correctional agencies, who viewed treatment with MOUD as a “substitute addiction” (Streisel, 2018).

4.6. Systemic barriers

Systemic barriers pertain to the interactions between the CJS and other service providers or service systems, and in particular, address the challenges of transitioning from correctional to community-based treatment with MOUD. Twelve studies described systemic barriers to the implementation of MOUD stemming from a lack of coordination between correctional facilities and community-based public safety officials, SUD treatment programs, or office-based MOUD treatment providers.

Police surveillance and harassment of individuals in community-based MOUD treatment programs was identified as a barrier to enrolling in treatment upon release to the community in several studies. This factor was cited in studies conducted in Ukraine (Mazhnaya et al., 2016); Bangkok, Thailand (Hayashi & Lianping, 2017); and Malaysia (Wickersham & Marcus, 2013). A lack of treatment capacity, both while incarcerated and in the community upon release, was cited as a barrier to transitioning to community-based MOUD treatment upon release in studies conducted in diverse settings, including in Puerto Rico (Albizu-Garcia et al., 2012); in a mixed methods study conducted with injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (Hayashi & Lianping, 2017); in a qualitative study with formerly incarcerated individuals and service providers in New York (Maradiaga & Nahvi, 2016); and focus groups conducted with physicians and other correctional staff in prisons in Iran (Moradi et al., 2015).

Lack of linkage or coordination between correctional and community MOUD treatment providers was cited as a barrier in a survey of physicians in prisons in Ontario, Canada; although about half of the sample had prescribed MOUD to prisoners, less than one fifth had initiated patients in custody due to these concerns (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2018). Limited referrals from prison to community-based MOUD treatment was cited in a survey of medical directors in state and federal prisons in the U.S. (Nunn & Zaller, 2009, 2010; Nunn et al., 2011), as well as in a survey of correctional staff who work directly with inmates in patient care or case management in Connecticut (Springer & Bruce, 2008). A study in Malaysia cited the lack of communication from prison personnel to police authorities as a barrier to engaging in community treatment with MOUD at release (Wickersham & Marcus, 2013). A qualitative study of 20 physicians in the U.S. examined barriers to office-based treatment with buprenorphine or extended release naltrexone for justice-involved patients (Andraka-Christou & Capone, 2018). Respondents most commonly cited as obstacles the overly burdensome reporting requirements, often without compensation by the CJS; discouragement from criminal justice administrators, primarily regarding buprenorphine treatment; and concerns that patient health information, such as urine test results, could be used to punish patients.

4.7. Facilitators of MOUD implementation in CJS

4.7.1. Institutional facilitators

Three studies identified institutional factors that facilitated implementation of MOUD within prisons. In a nationally representative survey of jails and prisons in the U.S., organizational factors were examined in relation to provision of detoxification services and pharmacological treatment for SUD (i.e., alcohol or opioids). Institutions that provided mental health counseling as well as pharmacological treatments for SUD were more likely to provide detox services; similarly, institutions that provided medications for mental health problems and detoxification services were more likely to provide pharmacological SUD treatment (Oser et al., 2009). Jails were significantly more likely to provide both types of services than prisons. An unanticipated finding was that higher scores on a scale measuring traditional criminal justice goals related to beliefs about punishment and sanctions (i.e., deterrence, incapacitation, and “just desserts”) were associated with higher odds of providing pharmacotherapies for SUD treatment.

A survey of governmental entities responsible for prison systems in 29 European countries found that opioid substitution treatment (OST) was available in prisons of most European countries, although it was unavailable in five countries. Moreover, greater OST capacity was associated with an established history of OST provision within the country, suggesting that accessibility within correctional systems is dependent on broader community accessibility of MOUD treatment (Zurhold & Stover, 2016). In another study with physicians in Ontario, Canada, support from institutional health care staff and administrative staff, adequate resources for program delivery, and access to linkage with community-based MOUD treatment providers were identified as facilitators of MOUD treatment in prison (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2018).

4.7.2. Programmatic facilitators

Three studies described programmatic practices that facilitated implementation of MOUD or beneficial effects that resulted from implementation of MOUD treatment in correctional settings. In a secondary analysis of data on MOUD prescribing in a prison in the U.K., the phased implementation of a general practitioner specialist in SUD led to an increase in methadone maintenance and detoxification treatments; over time the rate of methadone maintenance treatment plateaued with a corresponding decrease in the rate of methadone detox (Wright & French, 2014). In a qualitative study conducted in Dublin, Ireland, prison staff cited MOUD treatment as beneficial for reducing the supply of heroin and drug use within the prison, thereby leading to better management and control of inmates (Carlin, 2005). In a survey conducted with prisoners in England that asked about the sales price of diverted substances, the authors found that buprenorphine commanded a higher price than buprenorphine/naloxone (both inside and outside the prison), and hence was often subject to diversion, leading to a recommendation for use of the latter medication (Mohammed & Hughes, 2016; Wright, Mohammed, & Hughes, 2014).

Four studies reported on programmatic interventions that aimed to improve knowledge, attitudes, and/or use of medication-based treatment within correctional settings or in community corrections.

The Medication-Assisted Treatment Implementation in Community Correctional Environments (MATICCE) study examined the effects of a Knowledge, Perceptions and Information (KPI) intervention on increasing inter-organizational linkages between community corrections agencies and local treatment providers who provide MOUD for offenders under community supervision (Friedmann et al., 2013; Friedmann et al., 2015). Data on implementation challenges was obtained from the staff in the 20 community corrections agencies that were participating in a training intervention on use of MOUD and a cluster randomized trial of an organizational linkage intervention. Although training alone was associated with increases in familiarity with pharmacotherapy and knowledge of where to refer clients, the experimental intervention produced significantly greater improvements in functional attitudes (e.g., that medication treatment is helpful to clients) and referral intentions. Moreover, corrections staff demonstrated greater improvements in functional perceptions and intent to refer clients with OUD for treatment with MOUD than did treatment staff. Qualitative interviews conducted with study participants both before and after the intervention was implemented found that staff in both the correctional and treatment systems attributed poor working relationships to the lack of effective communication across systems, leading to limited interactions and skewed perceptions of individuals working in the other system (Monico & Mitchel, 2016).

In a quasi-experimental study, an intervention designed to increase knowledge about treatment with MOUD was tested with 37 state parole officers, Federal pre-detention officers, and Federal parole officers (Turban, 2012). Agreement with statements concerning common misconceptions about opioid addiction and methadone treatment was assessed both before and after exposure to a presentation outlining the benefits of treatment with MOUD. There was a statistically significant improvement at post-test, suggesting that an informational intervention may increase acceptability of MOUD among parole officers.

In another quasi-experimental study conducted with physicians in France, including those who worked in a specialized center for patients with OUD in prison, found that use of urine test strips was effective in monitoring patients using MOUD and improved the clinician’s ability to make appropriate changes in therapeutic strategy using test results (Victorri-Vigneau et al., 2016).

A two-part pilot test in a Northeastern state in the U.S. examined whether an online training intervention for criminal justice professionals increased treatment referrers’ and decision makers’ (a) knowledge of MOUD, (b) positive attitudes toward use of MOUD, and (c) willingness to refer criminal justice clients to MOUD treatment (Matejkowski, Dugosh, Clements, & Festinger, 2015). In the first study, 45 CJS treatment referrers who received the MOUD training had significantly higher scores at post-test relative to pre-test on knowledge items and on all measures assessing attitudes toward MOUD treatment and willingness to refer to MOUD treatment compared with those in the control group. In the second study, CJS decision makers also had significant increases in all but one of the scales assessed, indicating more knowledge and willingness to refer individuals to treatment with MOUD.

Lastly, two descriptive analyses described strategies for implementing MOUD in correctional settings. Chavez (2012) argues that expanding access to treatment with MOUD in correctional settings can be facilitated by prison nurses, with the goal of improving individual and public health. A descriptive analysis of collaborations among corrections and treatment providers to increase capacity for MOUD treatment provision in jails in New Mexico, including methadone and buprenorphine for both detoxification and maintenance, and prerelease buprenorphine, was based both on the evidence of its efficacy and its harm reduction potential (Trigg & Dickman, 2012).

4.7.3. Attitudinal facilitators

Four studies identified favorable attitudes among either prison staff or prisoners toward MOUD when it was viewed as a means for harm reduction related to drug injection and/or HIV transmission, as well as because of its beneficial effects on treating addiction and improving health. In a study that conducted semi-structured interviews with prison staff (n = 16) in Ireland, methadone maintenance treatment was generally viewed as beneficial in order to: (1) ensure continuity of harm-reduction policies from the community; (2) to reduce the supply of heroin in the prison; (3) prevent needle sharing and the spread of blood-borne infections; (4) treat heroin addiction; and (5) control prisoners and maintain order and discipline within the prison (Carlin 2005). In a secondary analysis of quantitative data on injection drug use while incarcerated among prisoners in two studies conducted in Australia, the authors concluded that treatment with MOUD in prison could reduce injection activity while incarcerated (Kinner, Moore et al., 2013).

Similarly, two in-depth qualitative studies conducted in Iran examined the attitudes of prison-based personnel and prisoners regarding the implementation of methadone maintenance programs in prisons, which was initiated in 2003 as a harm reduction strategy to reduce HIV transmission in prisons. In the first study, focus groups and interviews were conducted with 30 prisoners and 15 prison staff and health policy makers at one prison. Methadone treatment was viewed favorably because of its perceived health benefits to prisoners and positive effects on socio-economic status of prisoners’ families (Zamani et al., 2010). In a second, larger study, the investigators conducted 7 focus groups with prison physicians, consultants, psychologists, and experts and 7 focus groups with directors and managers of prisons, with a total of 140 participants (Moradi et al., 2015). The study identified generally positive attitudes toward methadone maintenance treatment because of its potential to reduce illegal drug use and high-risk injection and other risky behaviors among incarcerated individuals.

Two studies described characteristics of individuals that facilitated implementation of MOUD. A qualitative study of individuals incarcerated in Norway focused on the agency of incarcerated individuals that led to successful treatment with MOUD (Havnes, Clausen, & Middelthon, 2014). They suggested that individuals’ self-control, self-regulation, and motivation were instrumental to successful treatment with MOUD within the context of the “ceaseless surveillance” in a prison environment. In a study of 158 male inmates in Spain, who had been on methadone treatment for at least 3 months, two individual factors were associated with higher satisfaction with treatment. More positive attitudes were associated with individuals who were HIV+, perhaps reflecting its beneficial effects on reducing injection use, as well as among individuals who perceived that they had a greater influence on methadone dose changes, suggesting that more patient input into treatment led to more satisfaction (Marco et al., 2013).

Prior experiences with MOUD treatment and greater knowledge were associated with more favorable attitudes towards it use in three studies. In one study, although the majority of a sample of incarcerated men with OUD in Malaysia did not intend to seek treatment with MOUD, those who had greater severity of OUD, i.e., reported prior daily use and more negative consequences related to drug use, were more interested in initiating treatment with MOUD (Mukherjee & Wickersham, 2016). Similarly, in a study of HIV+ prisoners in Malaysia, about half believed that treatment with MOUD “would be helpful” and 54% of this subgroup felt it would prevent relapse after reentry. However, 70% of the sample was interested in learning more about treatment with MOUD and there were higher levels of satisfaction among those who had been previously treated with MOUD (Bachireddy & Bazazi, 2011). More knowledge about treatment with MOUD was also associated with more favorable attitudes towards its use among 56 individuals with OUD who had been recently released from prison in Moldova (Polonsky, Azbel et al., 2016).

Two studies described factors associated with positive attitudes toward MOUD treatment among staff in the CJS. Correctional agents who were interviewed in a qualitative study in the U.S. generally expressed negative attitudes about treatment with MOUD, however, those who had observed positive effects of MOUD treatment upon individuals they supervised expressed more favorable attitudes (Mitchell et al., 2016). Similarly, more knowledge about MOUD was associated with more favorable attitudes among 243 administrative, medical, and custodial prison staff in Ukraine (Polonsky & Azbel, 2015).