Abstract

West Nile virus infections can cause severe neurological symptoms. During the last 25 years, cases have been reported in Asia, North America, Africa, Europe and Australia (Kunjin). No West Nile virus vaccines or specific antiviral therapies are available to date. Various viral proteins and host-cell factors have been evaluated as potential drug targets. The viral protease NS2B–NS3 is among the most promising viral targets. It releases viral proteins from a non-functional polyprotein precursor, making it a critical factor of viral replication. Despite strong efforts, no protease inhibitors have reached clinical trials yet. Substrate-derived peptidomimetics have facilitated structural elucidations of the active protease state, while alternative compounds with increased drug-likeness have recently expanded drug discovery efforts beyond the active site.

Protease inhibitors of West Nile virus have long suffered from insufficient drug likeness, which has been tackled in latest advancements.

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV) is a flavivirus of the Flaviviridae family. It circulates through a mosquito–bird–mosquito cycle and is transmitted to humans via Culex mosquitoes.1–4 During the last 25 years, major local outbreaks in human populations occurred, for example, in Africa,5 the Middle East,5 North America6,7 and Europe.8–10 A WNV subtype referred to as Kunjin circulates in Oceania.11 Climate change is considered a driving force for the expansion of transmission areas and the extension of transmission seasons.12–14 Increasing temperatures are also suggested to intensify the transmission of WNV.13,15,16

Most WNV infections are either asymptomatic or associated with flu-like symptoms (West Nile fever).10,17,18 However, about 1 in 150 patients develops a clinically severe West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND),10,19,20 which can include encephalitis, meningitis or acute flaccid paralysis.10,21,22

No WNV vaccine candidate has proceeded beyond phase II clinical trials.23 In case of the closely related dengue virus, a phenomenon described as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) has challenged vaccine development programs. ADE has been suggested to increase viremia and disease severity after consecutive infections with different dengue serotypes.24–27 Whether cross-reactive antibodies promote the pathogenicity of WNV infections in areas of co-circulation with other flaviviruses is yet unclear.23,27,28

The flavivirus replication cycle offers a number of host factors and viral proteins as drug targets. Ideally, an antiviral drug would possess pan-flaviviral activity to combat infections with West Nile, dengue, Zika and other pathogenic flaviviruses.29,30 In what follows, drug discovery attempts targeting the WNV protease NS2B–NS3 (WNVpro) are discussed. WNVpro has received less attention by medicinal chemists than the related proteases of dengue virus or the recently emerged Zika virus. Thus, this article aims to move WNVpro into the focus of medicinal chemists and highlights recent advances in the field.

The West Nile virus protease NS2B–NS3 as drug target

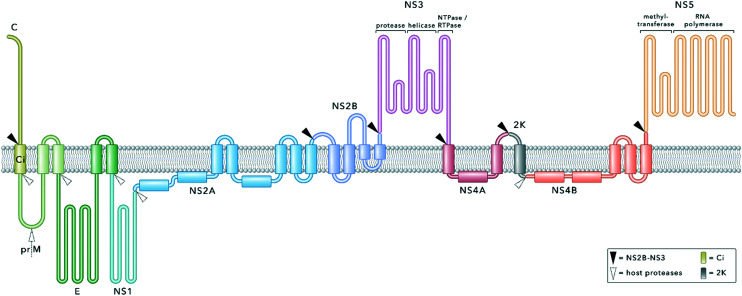

Flaviviruses contain a single-stranded RNA genome. Following cell entry and release into the cytoplasm, the genome is translated into a single polyprotein, which is embedded into the membrane of the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) (Fig. 1). Co- and post-translational processing by host proteases and the viral protease NS2B–NS3 at specific cleavage sites releases several structural and non-structural (NS) proteins necessary for genome replication and virion assembly.7,31,32 This critical role within the viral replication cycle qualifies NS2B–NS3 as a promising drug target (Fig. 1). Protease inhibitors have already proven effective therapeutics in the treatment of chronic viral infectious diseases such as HCV or HIV.33,34

Fig. 1. Model of the flavivirus polyprotein embedded into the ER membrane. The polyprotein comprises structural (capsid, C; membrane glycoprotein precursor, prM; envelope protein, E) and non-structural (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5) proteins. Proteolytic cleavage sites within the polyprotein are indicated with triangles. NS2B–NS3 processes all cytosolic cleavage sites. Host proteases are involved in cleaving residues inside the ER lumen. The capsid protein, NS3, NS5 and the small cofactor region of NS2B are exposed to the cytosolic site of the ER membrane whilst prM, E and NS1 face the ER lumen. Ci remains in the ER membrane after C and prM are released after proteolytic cleavage. During later stages of the viral replication cycle, the mature membrane protein (M) is released from prM by furin cleavage in the trans-Golgi apparatus. NS2A, NS2B, NS4A and NS4B are represented according to their proposed membrane topology reported in the literature.35–39 NS3 and NS5 are both multifunctional enzymes.31,40–43.

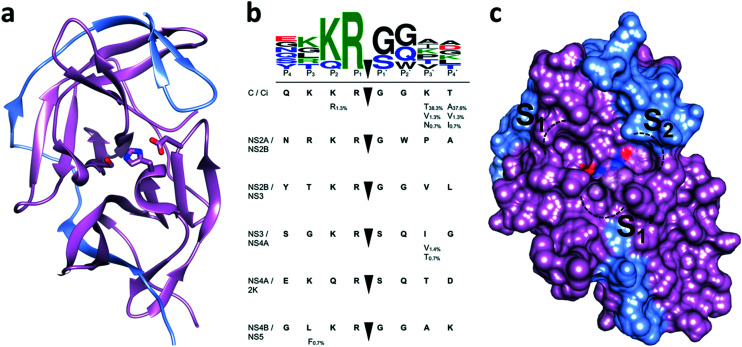

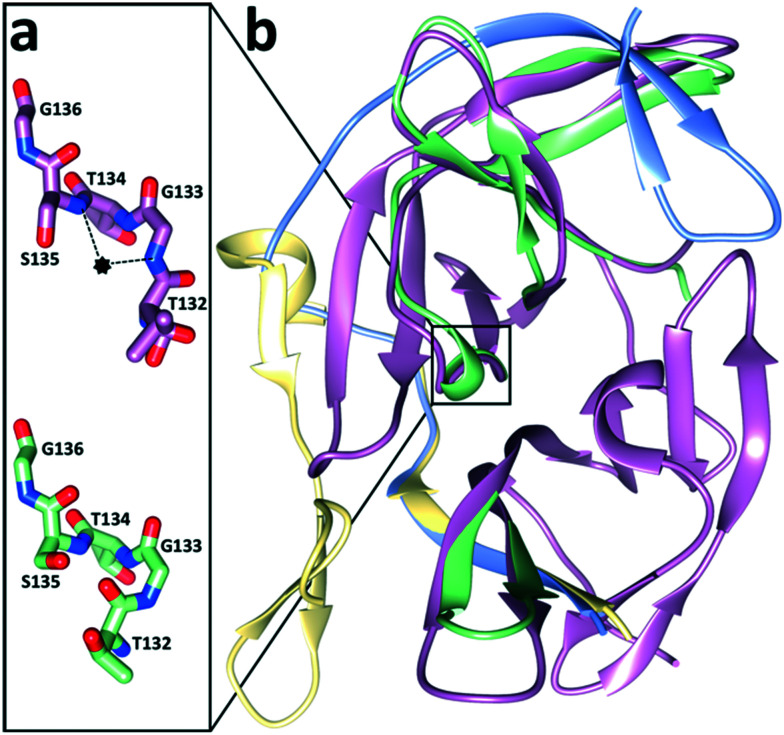

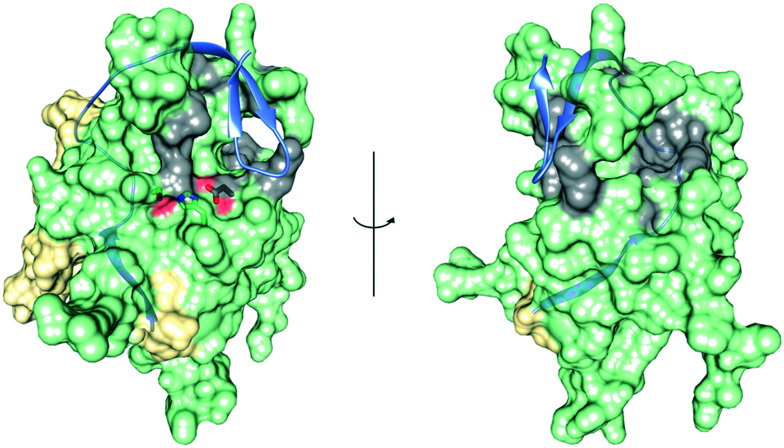

NS2B–NS3 consists of a serine protease domain located on the N-terminal part of NS3 and a small hydrophilic cofactor domain located on NS2B (Fig. 3a).44 Major parts of NS2B are hydrophobic and anchor the protease complex to the ER membrane (Fig. 1).36,45 Protease (NS3) and cofactor (NS2B) interact dynamically, resulting in various conformations that have been observed by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. In the catalytically active conformation, the C-terminal segment of NS2B forms a β-hairpin around the active site of NS3, which is not displayed in the inactive state (Fig. 2b).44,46 NMR studies of WNVpro in solution indicate an equilibrium of different conformations.47 The major conformation corresponds to the catalytically active state, commonly referred to as closed conformation. Less populated species indicate heterogeneous conformations of dissociated C-terminal NS2B. The oxyanion hole, critical to catalysis, has also been proposed in catalytically competent and incompetent forms (Fig. 2a).48 Structural studies of WNVpro and related flavivirus proteases have recently been reviewed comprehensively.48,49

Fig. 3. Active site and substrate specificity of WNVpro. NS2B is highlighted in light blue and NS3 in magenta. Graphics a) and c) were generated with UCSF Chimera.58 a) The co-crystallised ligand 16 is not shown.57 Residues of the catalytic triad are highlighted. b) Polyprotein cleavage sites recognised by WNVpro. Residues covering  are shown.50 Full-length sequences from human isolates reported in the NCBI protein bank (149 sequences) were analysed. For each cleavage site, the consensus sequence is highlighted in bold. Where applicable, alternative residues are indicated underneath the respective position. The total consensus sequence was plotted using WebLogo.59 c) Same as a), showing the surface area. Protease subsites critical for substrate recognition are indicated.

are shown.50 Full-length sequences from human isolates reported in the NCBI protein bank (149 sequences) were analysed. For each cleavage site, the consensus sequence is highlighted in bold. Where applicable, alternative residues are indicated underneath the respective position. The total consensus sequence was plotted using WebLogo.59 c) Same as a), showing the surface area. Protease subsites critical for substrate recognition are indicated.

Fig. 2. Conformational flexibility of WNVpro. a) Residues of the oxyanion hole. The oxyanion hole is indicated as a black star.53,55 The backbone NH atoms of S135 and G133 are crucial for the oxyanion hole formation.53,55 In the active form (magenta), these residues promote catalysis through hydrogen bond formation with the carbonyl oxygen of the substrate.53,56 In contrast, in the catalytically incompetent form (lime green) the NH backbone of G133 is flipped.44,53,57 b) Superimposition of the closed (NS2B in light blue and NS3 in magenta)56 and open state (NS2B in yellow and NS3 in lime green).53 Parts of NS3 with identical backbone conformations in both states are shown in magenta. Graphics were generated with UCSF Chimera.58.

Like NS2B–NS3 proteases from other flaviviruses, WNVpro shows a preference to cleave peptide sequences after two basic residues such as lysine or arginine. Following the Schechter and Berger nomenclature for protease subsites,50 this specificity is determined by key residues in S1 (e.g. Asp129, Tyr130 and Tyr161 of NS3) and S2 (e.g. Asp82 and Asn84 of NS2B) interacting with basic side chains in P1 and P2via hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions.48,50–53 This substrate specificity is supported by a comprehensive analysis of all cleavage sites processed by the WNVpro based on full-length human isolates conducted for this article (Fig. 3b). Our study confirms conservation for arginine in P1, a pronounced preference for lysine over arginine in P2 and a strong preference for small amino acids like glycine or serine in  . Other positions appear to tolerate many residues. Hence,

. Other positions appear to tolerate many residues. Hence,  determine the specificity of WNVpro (Fig. 3c). The data align very well with a recent analysis of polyprotein cleavage sites of the related Zika virus protease.54 Both proteases display full conservation for P1 arginine over all polyprotein cleavage sites, informing drug discovery campaigns of substrate-based inhibitors.

determine the specificity of WNVpro (Fig. 3c). The data align very well with a recent analysis of polyprotein cleavage sites of the related Zika virus protease.54 Both proteases display full conservation for P1 arginine over all polyprotein cleavage sites, informing drug discovery campaigns of substrate-based inhibitors.

Strategies for WNVpro drug discovery

The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5 lacks proof-reading function, resulting in an increased probability for mutations during viral replication.30,60 Some mutations remain without effect on the protease's activity, while others may compromise the enzyme's catalytic activity. Mutations in the substrate binding pocket of NS2B–NS3 are likely to result in substantial loss of enzymatic activity which is reflected in high conservation of active-site residues among proteases from different falviviruses.34,49 Consequently, initial studies mainly focused on the active site. However, these efforts were challenged by its poor druggability, partially due to the conserved dibasic recognition motif in S1 and S2 and partially due to its shallow structure.49,61 Thus, an increasing number of more recent studies have shifted their focus towards allosteric binding sites or the perturbation of the interactions between NS2B and NS3. Details for both types of compounds can be found in Table 1.

Supplementary data for selected WNV protease inhibitors.

| Compound no. | Anti-WNV activitya [μM] | Comments | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS2B–NS3 | Cellular | |||

| 2 | K i = 92.564 | K i = 24.9 μM for the dipeptide analogue lacking norleucine at the C-terminus64 | 64, 127 | |

| 4 | K i = 4966 | 66 | ||

| 5 | IC50 = 1.9767 | 66 | ||

| 6 | K i = 1.30 | 67 | ||

| 7 | IC50 = 1.60 | Non-basic 4-acetylamino-l-phenylalanine derivative in P1 displayed similar inhibition | 68 | |

| 8 | IC50 = 0.22 | 69 | ||

| 9 | K i = 0.039 | EC50 = 23.36 | 69 | |

| 10 | K i = 0.009 | EC50 = 1.6 | Aldehyde showed favourable serum stability in comparison to the carboxylate | 76 |

| 11 | IC50 = 0.12 | IC50 = 0.17 μM (acetyl analogue) | 78 | |

| 12 | K i = 0.082 | EC50 = 38 | Pan-flaviviral NS2B–NS3 inhibition: Zika virus (Ki = 0.04 μM); dengue virus (Ki = 0.051 μM) | 56 |

| CC50 > 100 | ||||

| 13 | IC50 = 22.5 | 71 | ||

| 14 | K i = 0.4 | 89 | ||

| 15 | K i = 2.05 | IC50 > 100 μM (thrombin) | 84 | |

| 16 | K i = 0.13 | K i > 200 μM (fXa); Ki > 500 μM (thrombin) | 57 | |

| 17 | K i = 0.069 | Pan-flaviviral NS2B–NS3 inhibition: Zika virus (Ki = 0.0017 μM); dengue virus (Ki = 0.160 μM) | 88 | |

| 18 | IC50 = 1.8 | CC50 > 50 | EC50 = 20 μM (dengue virus) | 72 |

| 19 | K i = 1390 | Irreversible inhibition in the presence of redox-active reagents (ascorbate and H2O2) | 90, 91 | |

| 20 | IC50 = 0.10592 | 2,4-Difluorobenzoate derivative showed an increase in half-life (∼3-fold) but ∼19-fold lower inhibition95 | 92–95 | |

| 21 | K i = 3.496 | EC50 = 1.496 | IC50 > 50 μM (trypsin); IC50 > 50 μM (fXa);96 substitution of the ortho-hydroxy-phenyl moiety by a meta-benzoyloxy-phenyl residue resulted in a 3-fold increase in inhibition97 | 96, 97 |

| CC50 = 14096 | ||||

| 22 | IC50 = 0.7 | CC50 = 29.2 | EC50 ∼ 2 μM (dengue virus) | 99 |

| 23 | IC50 = 1.2 | 106 | ||

| 24 | IC50 ∼ 180100 | K d = 40 μM (determined by NMR)100 | 100, 101 | |

| 25 | IC50 = 2.8 | 102 | ||

| 26 | K i = 4.6 | 103 | ||

| 27 | K i = 7.4 | 105 | ||

| 28 | IC50 = 30 | 107 | ||

| 29 | K i = 5.55 | 108 | ||

| 30 | IC50 = 4.22 | 110 | ||

| 31 | K i = 3.06 | CC50 > 300 | Inhibits dengue virus in cellular assay (EC50 ranging from 14 to 70 μM depending on the serotype) | 111 |

| 32 | IC50 = 3.9 | 115 | ||

| 33 | IC50 = 0.12 | Pan-flaviviral NS2B–NS3 inhibition: Zika virus (IC50 = 0.71 μM); dengue virus (IC50 = 0.2 μM); co-crystallised structure solved for dengue virus (accession code: 6MO2) | 112 | |

| 34 | K i = 4.47 | 120 | ||

| 35 | IC50 = 6.1 | 121 | ||

| 36 | K i = 2.8 | 122 | ||

| 37 | K i = 1.25 | CC50 > 250 | Inhibits dengue virus in cellular assay (EC50 ranging from 1.8 to 30 μM depending on the serotype) | 123 |

| 38 | K i ∼ 500 | 124 | ||

| 39 | EC50 = 1.27 | Pan-flaviviral inhibition in cellular assay: Zika virus (EC50 = 1.0 μM); dengue virus (EC50 = 0.81 μM) | 116 | |

| CC50 = 48.8 | ||||

| 40 | EC50 = 0.01 | In vivo protection of mice from lethal challenge of Zika virus; pan-flaviviral inhibition in cellular assay: Zika virus (EC50 = 0.022 μM); dengue virus (EC50 = 0.020 μM) | 117 | |

| EC90 = 0.03 | ||||

| CC50 = 40.7 | ||||

| 41 | EC50 = 0.66 | Pan-flaviviral inhibition in cellular assay: Zika virus (EC50 = 0.62 μM); dengue virus (EC50 = 1.2 μM) | 118 | |

| 42 | IC50 = 0.44 | EC50 = 17.0 | IC50 > 100 μM (furin) | 125 |

| CC50 > 200 | ||||

| 43 | IC50 = 22 | Modified analogue of zafirlukast (IC50 = 32 μM) | 126 | |

IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration in biochemical protease assays; Ki, inhibition constant; EC50, half maximal effective concentration in cellular viral infection assays or replicon assays; CC50, 50% cytotoxic concentration; Kd, dissociation constant.

Peptidomimetic active-site inhibitors

A common strategy in the development of peptide-based protease inhibitors is the use of substrate sequences as templates. Subsequent structure–activity relationships often aim to reduce molecular weight and peptidic character, while improving affinity. In case of serine, cysteine and threonine proteases, covalent modifiers can lead to additional activity gains. This strategy proved successful, for example, in the discovery of the first approved HCV protease inhibitors.62,63 Thus, early WNVpro drug discovery campaigns used similar strategies.

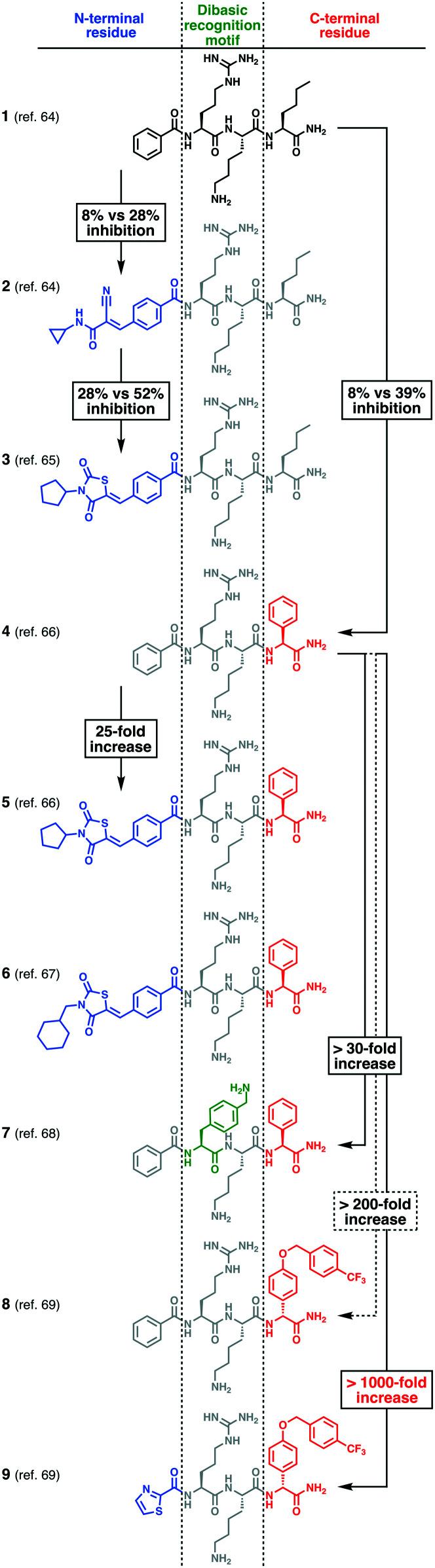

A long-term campaign that transformed initially weakly binding substrate analogues into high-affinity NS2B–NS3 ligands has been conducted by Klein and co-workers over the past 10 years (Fig. 4).64–70 Based on the initial lead compound 1, optimised derivatives were developed which all comprise an N-terminal cap, a central dibasic recognition motif and a C-terminal hydrophobic  residue (Fig. 4). Replacing a lysine residue by a benzylamine side chain (7) was the major improvement of the central recognition motif.68 Much higher affinity gains of up to three orders of magnitude were achieved by introducing hydrophobic N-terminal caps and C-terminal

residue (Fig. 4). Replacing a lysine residue by a benzylamine side chain (7) was the major improvement of the central recognition motif.68 Much higher affinity gains of up to three orders of magnitude were achieved by introducing hydrophobic N-terminal caps and C-terminal  residues, resulting in clearly nanomolar inhibitors of NS2B–NS3 (e.g.9).69 The large hydrophobic moiety in 8 and 9 is particularly important for high affinity and has been suggested to bind to the

residues, resulting in clearly nanomolar inhibitors of NS2B–NS3 (e.g.9).69 The large hydrophobic moiety in 8 and 9 is particularly important for high affinity and has been suggested to bind to the  site.71 Unfortunately, no experimental structural data are available for any of these compounds to elucidate their binding interactions. Compound 9 displays extraordinarily high target affinity, but three orders of magnitude lower antiviral activity in cells (Table 1). Attempts to improve the metabolic stability and drug-likeness of related compounds were accompanied by a significant affinity decrease (e.g.18).70,72 While this manuscript was under peer-review, a series of peptide analogues were published which do not require any basic residues to display low-micromolar activity against WNVpro and sub-micromolar antiviral activity in cell-based assays (DENV2).73

site.71 Unfortunately, no experimental structural data are available for any of these compounds to elucidate their binding interactions. Compound 9 displays extraordinarily high target affinity, but three orders of magnitude lower antiviral activity in cells (Table 1). Attempts to improve the metabolic stability and drug-likeness of related compounds were accompanied by a significant affinity decrease (e.g.18).70,72 While this manuscript was under peer-review, a series of peptide analogues were published which do not require any basic residues to display low-micromolar activity against WNVpro and sub-micromolar antiviral activity in cell-based assays (DENV2).73

Fig. 4. Selected compounds from a multistage peptide-based drug discovery campaign. Compounds are characterised by an N-terminal cap (blue), a dibasic recognition motif (green) and a C-terminal  residue (red). Affinity differences of compounds 2,643,654,665,666,677,68869 and 969 (WNVpro) are indicated in relation to the initial lead compound 164 (by comparison of IC50 and Ki values). Percent inhibition values are reported for the following conditions: WNVpro 150 nM, inhibitor 50 μM, substrate 50 μM; KM = 212 μM.

residue (red). Affinity differences of compounds 2,643,654,665,666,677,68869 and 969 (WNVpro) are indicated in relation to the initial lead compound 164 (by comparison of IC50 and Ki values). Percent inhibition values are reported for the following conditions: WNVpro 150 nM, inhibitor 50 μM, substrate 50 μM; KM = 212 μM.

Various studies combined substrate-derived peptides with electrophilic C-terminal warheads targeting S135 of the catalytic triad (Fig. 5b and c).56,71,74–78

Fig. 5. Selected substrate mimetics and their co-crystallised structures. a) Compound 12 in the substrate binding site of WNVpro. Hydrogen bonds between ligand and protein are indicated. b) Structures of selected peptide-based WNVpro inhibitors. Peptides 10–14 are covalent modifiers of Ser135 (warheads highlighted in red). The co-crystallised compound 12 is coloured as in a). c) Selected co-crystallised compounds and their PDB accession codes.44,55–57.

Most studies focused on a C-terminal aldehyde, which proved to be very useful to generate structural insights into interactions between NS2B–NS3 and substrate-derived inhibitors.74,76–78 High-affinity tetrapeptides were stepwise reduced to tri- and dipeptides of similar activity, indicating a major importance of P1 and P2 residues. Compound 10 is among the most potent inhibitors of this class and also surprisingly active in cells.76

Peptides containing a more drug-like boronate warhead were initially studied as inhibitors of dengue NS2B–NS375 and later optimised into a series of dipeptides targeting WNVpro and other flaviviral proteases (e.g.12).56 In contrast to aldehyde warheads, boronic acids have been proven to be part of approved drugs targeting the proteasome.79–81 Boronate peptides emerged as valuable tools to study NS2B–NS3 by X-ray and NMR (Fig. 5a), but are limited with respect to their selectivity and cellular activity.56,82,83 Recently, β-lactam analogues were studied as WNVpro inhibitors for the first time (e.g.13). The β-lactam moiety can modify Ser135, however, the covalent enzyme-inhibitor complex was found to hydrolyse rather rapidly.71

The critical role of P1 arginine offered opportunities for the exploration of various arginine mimetics (15–18, Fig. 5b).57,84–87 For instance, trans-(4-guanidino)cyclohexylmethylamide (GCMA), as in inhibitor 16, was identified as one of the best performing arginine mimetics targeting WNVpro.57 The co-crystal structure of WNVpro and 16 revealed an intramolecular hydrogen bond (bridging the N-terminal cap and P1 side chain),57 which was exploited to develop the first macrocyclic active-site inhibitor of WNVpro (17).88 Cyclisation was facilitated by two major chemical modifications, retaining the crucial orientation of the P1 residue.

Peptides furnished with C-terminal phosphonates (e.g.14) react irreversibly with Ser135 and are thus valuable starting points for probe design if linked to reporter molecules.89 Copper-binding peptides comprising the ATCUN motif like 1990 were shown to irreversibly damage the active site of WNVpro through oxidative modifications.90,91

Small molecules

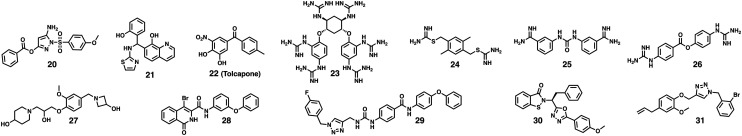

The majority of non-peptide inhibitors originated from high-throughput screening campaigns, including in silico screenings. Given the various starting points of these drug discovery campaigns, this class of inhibitors is structurally much more diverse than the peptide-based inhibitors (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Selected small-molecule inhibitors of WNVpro. Compounds 20,92,9521,96–982299 and 23106 originated from HTS campaigns. Compounds 24,100,10125,10226103 and 27105 were identified through virtual screenings. 28 is based on previous studies targeting α-chymotrypsin. Predicted binding of 28 to the active site is solely based on computational studies.107 The 1,2,3-triazole in 29 was hypothesised as a suitable moiety to bind to NS2B–NS3 based on the examination of crystal structures.10830 was derived from a focused in-house library screening.109,11031 was part of a study evaluating three distinct scaffolds with reported antiviral activity against HIV, HCV and herpes simplex virus.111.

Johnston and co-workers screened more than 65 000 compounds and identified inhibitors bearing an amino-pyrazole motif (e.g.20) as WNVpro inhibitors.92 Later studies on similar compounds targeting alternative NS2B–NS3 proteases from dengue93 and Zika viruses94 revealed covalent modification of Ser135 via a transesterification mechanism, strongly suggesting a similar inhibition mechanism for WNVpro. The high reactivity of the pyrazole ester in 20 and analogues is essential for their activity but also their major weakness with respect to stability and drug-likeness.95 Two alternative high-throughput screenings discovered 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives (e.g.21)96–98 and tolcapone99 (22) as sub-micromolar WNVpro Inhibitors.

In silico screenings obviously present a cost-effective alternative to high-throughput screenings. WNVpro inhibitors 24,100,10125102 and 26103 all originated from virtual screening campaigns. In case of 26, which is related to commonly employed broad spectrum protease inhibitors, a covalent modification of Ser135 via transesterification was suggested.104 Attempts to improve its activity proved challenging.104 Recently, another in silico screening campaign identified, among others, 27 which is also active against the protease from Zika virus.105 Both tertiary amines in 27 are likely to mimic the basic P1 and P2 side chains of the substrate.

Targeting exosites – inhibitors with alternative binding modes

One major conclusion that can be drawn from the discussed attempts targeting the active site of WNVpro is that high-affinity inhibitors usually require either a dibasic recognition motif or covalent modifiers. Unfortunately, both properties provide major challenges for drug discovery and are one of the reasons why no compound has yet reached clinical trials. Naturally, recent attention has shifted towards alternative binding sites of NS2B–NS3 to generate inhibitors that may potentially act allosterically or prevent the association of NS2B and NS3 (Fig. 7).

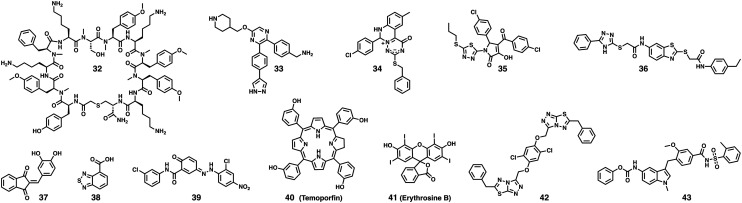

Fig. 7. Targeting exosites of WNVpro. Compound 32 was the first macrocyclic peptide reported to bind to an exosite of WNVpro.115 Compounds 33,11234,12035121 and 36122 originated from different in-house library screenings. 37 resulted from a study evaluating Knoevenagel condensation products.12338 emerged from a fragment-based screening campaign utilising an STD-NMR readout.124 Compounds 39,11640117 and 41118 were found through HTS. 42 was identified through virtual screening.12543 is a derivative of an FDA-approved drug (zafirlukast).126.

Compound 33 and analogues were optimised from screening hits of an in-house library targeting unrelated enzymes.112 The campaign mainly targeted Zika virus with proven antiviral activity in cells and animal models. The compounds are also active against related proteases like WNVpro. Inhibition is non-competitive and co-crystal structures with the protease from dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV2) indicate a potentially allosteric binding mode.112 However, due to insufficient ligand electron density, the crystallographic results are subject of debate.113,114

Another campaign that also mainly targeted Zika virus used the Random nonstandard Peptide Integrated Discovery (RaPID) mRNA display technique to screen for macrocyclic NS2B–NS3 binders that include non-canonical amino acids. Remarkably, all enriched peptide sequences that were selected clearly displayed non-competitive inhibition, suggesting a potentially allosteric inhibition mode. Among all sequences that were highly active inhibitors of Zika NS2B–NS3, only compound 32 showed significant inhibition of WNVpro, indicating that non-competitive inhibitors can more specifically target individual flavivirus proteases than active-site inhibitors.115 This might invite diagnostic applications in areas where various flaviviruses co-circulate.

Conformational switch assays have been developed to screen for inhibitors that interrupt the interactions between NS2B and NS3.116,117 Non-competitive inhibitors resulting from screenings which used these assays are 39, 40 (temoporfin) and 41 (erythrosine B).116–118 The importance of N152 and V154 (adjacent to the active site) for interactions with 39 was confirmed by mutagenesis of DENV2 protease.116 Although approved as a photosensitiser, temoporfin's mode of action is reported to be not dependent on photoactivation.117 Erythrosine B is approved as a food additive.

For most of the compounds discussed in this section (Fig. 7), an allosteric mode of action has not been proven beyond doubt. Non-competitive inhibition in an enzymatic assay is an indication but usually insufficient evidence for allostery as there are many ways compounds can interfere with bioassays, particularly during high-throughput screenings. Thus, selective binding and inhibition should be confirmed by additional orthogonal methods, particularly if compounds are prone to interfere with biochemical assays, such as typical PAINS structures (e.g. quinone or catechol)119 or compounds that may interfere with fluorescence-based assays triggered by own fluorescence or strong chromophores (e.g. erythrosine or temoporfin). Interestingly, the majority of compounds are suggested to bind adjacent to the active site in close proximity to the C-terminal β-hairpin of NS2B (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Clusters of proposed exo binding sites. Superimposition of the open (NS2B is yellow, NS3 is lime green)53 and the closed state (NS2B is highlighted as ribbon in light blue)56 of WNVpro. Exo sites accumulated from proposed binding mechanisms of compounds 33, 34, 35, 36, 39, 42 and 43 are highlighted in grey. The catalytic triad is shown. Graphics were generated with UCSF Chimera.58.

Conclusion

West Nile virus has frequently raised global health concerns.5–10,128 The critical role of its protease NS2B–NS3 in the viral replication cycle qualifies it as a promising drug target.7,31,32 However, intensive research during the past two decades has revealed the limited druggability of WNVpro.

Many potent inhibitors were based on substrate derived peptidomimetics. This class of compounds has undoubtedly contributed to important structural elucidations of WNVpro. However, they also share common liabilities, mainly associated with the dibasic recognition motif, resulting in poor drug-likeness and limited selectivity. Achievements like the tolerance for very hydrophobic moieties (e.g.9) or macrocyclisation (e.g.17) may provide an avenue to eventually overcome these challenges.

Small molecules provide an alternative to fully avoid the challenges associated with peptide-based ligands. However, so far, small molecules that bind to the active site suffer from low affinity if not equipped with warheads, such as activated esters, indicating poor druggability of the active site.

The search for compounds that bind to alternative binding sites to trigger allosteric inhibition or interrupt the interactions between NS2B and NS3 has just begun and produced already an astonishing variety of promising compounds, ranging from small molecules to large macrocyclic peptides. Although, the resistance barrier is likely to be lower, allosteric inhibition might be the most promising route towards clinically relevant inhibitors of WNVpro and proteases of related flaviviruses.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C. N. thanks the Australian Research Council for a Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE190100015) and Discovery Project funding (DP200100348).

Biographies

Biography

Saan Voss.

Saan is a PhD candidate in the Research School of Chemistry at the Australian National University where he is working with Christoph Nitsche. He was trained in pharmaceutical sciences at the Institute of Pharmacy of the Freie Universität Berlin, where he has worked in the laboratory of Prof. Jörg Rademann. Saan has gained international experience in academia and industry. His PhD focuses on the development of antiviral agents targeting West Nile and Zika viruses, and on new synthetic strategies to generate constrained peptides.

Biography

Christoph Nitsche.

Christoph is a Senior Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow in the Research School of Chemistry at the Australian National University. Christoph studied chemistry and business administration and obtained his PhD in medicinal chemistry from Heidelberg University with Prof. Christian Klein. He worked as a Feodor Lynen Fellow at the Australian National University and as a Rising Star Fellow at the Free University of Berlin. His research program in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology currently focuses on drug discovery for infectious diseases, biocompatible chemistry, and peptide and protein modification.

References

- Campbell G. L. Marfin A. A. Lanciotti R. S. Gubler D. J. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002;2:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpitts T. M. Conway M. J. Montgomery R. R. Fikrig E. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25:635–648. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00045-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminade C. McIntyre K. M. Jones A. E. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019;1436:157–173. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaijk P. Luytjes W. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:337–344. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1389363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chancey C. Grinev A. Volkova E. Rios M. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:376230. doi: 10.1155/2015/376230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash D. Mostashari F. Fine A. Miller J. O'Leary D. Murray K. Huang A. Rosenberg A. Greenberg A. Sherman M. Wong S. Layton M. T. W. N. O. R. W. Group N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1807–1814. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson T. C. Diamond M. S. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:796–812. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0714-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L. L. Popovici F. Alexander Jr. J. P. Laurentia V. Tengelsen L. A. Cernescu C. Gary, Jr. H. E. Ion-Nedelcu N. Campbell G. L. Tsai T. F. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;179:230–233. doi: 10.1086/314566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambri V. Capobianchi M. Charrel R. Fyodorova M. Gaibani P. Gould E. Niedrig M. Papa A. Pierro A. Rossini G. Varani S. Vocale C. Landini M. P. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013;19:699–704. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki T. Lancet. 2018;392:1000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. A. Scherret J. H. Mackenzie J. S. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;951:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz S. Emerging Top. Life Sci. 2019;3:143–152. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20180124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz S. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B. 2015;370:20130561. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan J. Sathiakumar N. Bull. W. H. O. 2010;88:163. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.076034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover K. C. Barker C. M. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 2016;7:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Rocklöv J. Dubrow R. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:479–483. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K. O. Walker C. Gould E. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011;139:807–817. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanna I. J. Slifka M. K. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2014;13:589–608. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.906309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen L. R. Carson P. J. Biggerstaff B. J. Custer B. Borchardt S. M. Busch M. P. Epidemiol. Infect. 2013;141:591–595. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostashari F. Bunning M. L. Kitsutani P. T. Singer D. A. Nash D. Cooper M. J. Katz N. Liljebjelke K. A. Biggerstaff B. J. Fine A. D. Layton M. C. Mullin S. M. Johnson A. J. Martin D. A. Hayes E. B. Campbell G. L. Lancet. 2001;358:261–264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L. E. DeBiasi R. Goade D. E. Haaland K. Y. Harrington J. A. Harnar J. B. Pergam S. A. King M. K. DeMasters B. K. Tyler K. L. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:286–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt E. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:1184. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30616-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbert S. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019;15:2337–2342. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1621149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith A. Ooi E. E. Horstick O. Wills B. Lancet. 2019;393:350–363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar S. Luedtke A. Langevin E. Zhu M. Bonaparte M. Machabert T. Savarino S. Zambrano B. Moureau A. Khromava A. Moodie Z. Westling T. Mascareñas C. Frago C. Cortés M. Chansinghakul D. Noriega F. Bouckenooghe A. Chen J. Ng S. P. Gilbert P. B. Gurunathan S. DiazGranados C. A. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:327–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. B. Vaccine. 2017;35:6355–6358. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey F. A. Stiasny K. Vaney M. C. Dellarole M. Heinz F. X. EMBO Rep. 2018;19:206–224. doi: 10.15252/embr.201745302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardina S. V. Bunduc P. Tripathi S. Duehr J. Frere J. J. Brown J. A. Nachbagauer R. Foster G. A. Krysztof D. Tortorella D. Stramer S. L. García-Sastre A. Krammer F. Lim J. K. Science. 2017;356:175–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinigaglia A. Peta E. Riccetti S. Barzon L. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2020;15:333–348. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2020.1714586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldescu V. Behnam M. A. M. Vasilakis N. Klein C. D. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2017;16:565–586. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeldt C. J. Cortese M. Acosta E. G. Bartenschlager R. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:125–142. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrows N. J. Campos R. K. Liao K. C. Prasanth K. R. Soto-Acosta R. Yeh S. C. Schott-Lerner G. Pompon J. Sessions O. M. Bradrick S. S. Garcia-Blanco M. A. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4448–4482. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leuw P. Stephan C. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018;19:577–587. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1454428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K. Osswald H. L. Prato G. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:5172–5208. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X. Gayen S. Kang C. Yuan Z. Shi P. Y. J. Virol. 2013;87:4609–4622. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02424-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Li Q. Wong Y. L. Liew L. S. Kang C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:2244–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. Kastner S. Krijnse-Locker J. Bühler S. Bartenschlager R. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8873–8882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. Sparacio S. Bartenschlager R. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8854–8863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Kim Y. M. Zou J. Wang Q. Y. Gayen S. Wong Y. L. Lee le T. Xie X. Huang Q. Lescar J. Shi P. Y. Kang C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:3150–3157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengler G. Wengler G. Virology. 1991;184:707–715. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90440-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowski P. Niebuhr A. Mueller O. Bretner M. Felczak K. Kulikowski T. Schmitz H. J. Virol. 2001;75:3220–3229. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3220-3229.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengler G. Wengler G. Virology. 1993;197:265–273. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yon C. Teramoto T. Mueller N. Phelan J. Ganesh V. K. Murthy K. H. Padmanabhan R. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27412–27419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbel P. Schiering N. D'Arcy A. Renatus M. Kroemer M. Lim S. P. Yin Z. Keller T. H. Vasudevan S. G. Hommel U. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:372–373. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum S. Ebner K. E. Padmanabhan R. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30715–30723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Holloway S. Schirmeister T. Klein C. D. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:11348–11381. doi: 10.1021/cr500233q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X. C. Ozawa K. Qi R. Vasudevan S. G. Lim S. P. Otting G. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam M. A. M. Klein C. D. P. Biochimie. 2020;174:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Biophys. Rev. 2019;11:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s12551-019-00508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter I. Berger A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell K. J. Stoermer M. J. Fairlie D. P. Young P. R. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38448–38458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell K. J. Nall T. A. Stoermer M. J. Fang N. X. Tyndall J. D. Fairlie D. P. Young P. R. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:2896–2903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleshin A. E. Shiryaev S. A. Strongin A. Y. Liddington R. C. Protein Sci. 2007;16:795–806. doi: 10.1110/ps.072753207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss S. Nitsche C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;30:126965. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.126965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin G. Chappell K. Stoermer M. J. Hu S. H. Young P. R. Fairlie D. P. Martin J. L. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:1568–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Zhang L. Weigel L. F. Schilz J. Graf D. Bartenschlager R. Hilgenfeld R. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammamy M. Z. Haase C. Hammami M. Hilgenfeld R. Steinmetzer T. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:231–241. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F. Goddard T. D. Huang C. C. Couch G. S. Greenblatt D. M. Meng E. C. Ferrin T. E. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G. E. Hon G. Chandonia J. M. Brenner S. E. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belshaw R. Gardner A. Rambaut A. Pybus O. G. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008;23:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018;1062:175–186. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8727-1_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J. A. Rudd M. T. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016;30:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong A. D. Kauffman R. S. Hurter P. Mueller P. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:993–1003. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Behnam M. A. Steuer C. Klein C. D. Antiviral Res. 2012;94:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Schreier V. N. Behnam M. A. Kumar A. Bartenschlager R. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:8389–8403. doi: 10.1021/jm400828u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam M. A. Nitsche C. Vechi S. M. Klein C. D. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1037–1042. doi: 10.1021/ml500245v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos Lima A. Behnam M. A. El Sherif Y. Nitsche C. Vechi S. M. Klein C. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:5748–5755. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel L. F. Nitsche C. Graf D. Bartenschlager R. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:7719–7733. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam M. A. Graf D. Bartenschlager R. Zlotos D. P. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:9354–9370. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob A. Sundermann T. R. Klein C. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;29:1913–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazǐć T. Kopf S. Corridan J. Leuthold M. M. Bertoša B. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:140–156. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühl N. Graf D. Bock J. Behnam M. A. M. Leuthold M. M. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:8179–8197. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühl N. Leuthold M. M. Behnam M. A. M. Klein C. D. J. Med. Chem. 2021;64:4567–4587. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J. E. Ma N. L. Yin Z. Patel S. J. Wang W. L. Chan W. L. Ranga Rao K. R. Wang G. Ngew X. Patel V. Beer D. Lim S. P. Vasudevan S. G. Keller T. H. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6585–6590. doi: 10.1021/jm0607606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. Patel S. J. Wang W. L. Wang G. Chan W. L. Rao K. R. Alam J. Jeyaraj D. A. Ngew X. Patel V. Beer D. Lim S. P. Vasudevan S. G. Keller T. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:36–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoermer M. J. Chappell K. J. Liebscher S. Jensen C. M. Gan C. H. Gupta P. K. Xu W. J. Young P. R. Fairlie D. P. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:5714–5721. doi: 10.1021/jm800503y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüller A. Yin Z. Brian Chia C. S. Doan D. N. Kim H. K. Shang L. Loh T. P. Hill J. Vasudevan S. G. Antiviral Res. 2011;92:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C. Gayen S. Wang W. Severin R. Chen A. S. Lim H. A. Chia C. S. Schüller A. Doan D. N. Poulsen A. Hill J. Vasudevan S. G. Keller T. H. Antiviral Res. 2013;97:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramore A. Frantz S. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2003;2:611–612. doi: 10.1038/nrd1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Serrano I. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5:107–114. doi: 10.1038/nrd1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plescia J. Moitessier N. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;195:112270. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J. Hansen G. Nitsche C. Klein C. D. Zhang L. Hilgenfeld R. Science. 2016;353:503–505. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. N. Nitsche C. Pilla K. B. Graham B. Huber T. Klein C. D. Otting G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4539–4546. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H. A. Joy J. Hill J. San Brian Chia C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:3130–3134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H. A. Ang M. J. Joy J. Poulsen A. Wu W. Ching S. C. Hill J. Chia C. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;62:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang M. J. Li Z. Lim H. A. Ng F. M. Then S. W. Wee J. L. Joy J. Hill J. Chia C. S. Peptides. 2014;52:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouretova J. Hammamy M. Z. Epp A. Hardes K. Kallis S. Zhang L. Hilgenfeld R. Bartenschlager R. Steinmetzer T. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017;32:712–721. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2017.1306521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun N. J. Quek J. P. Huber S. Kouretova J. Rogge D. Lang-Henkel H. Cheong Z. K. E. Chew B. L. A. Heine A. Luo D. Steinmetzer T. ChemMedChem. 2020;15:1439–1452. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoreński M. Milewska A. Pyrć K. Sieńczyk M. Oleksyszyn J. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019;34:8–14. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1506772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham A. M. Yu Z. Cowan J. A. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:980–988. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham A. M. Yu Z. Cowan J. A. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:12357–12360. doi: 10.1039/c8cc07448h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston P. A. Phillips J. Shun T. Y. Shinde S. Lazo J. S. Huryn D. M. Myers M. C. Ratnikov B. I. Smith J. W. Su Y. Dahl R. Cosford N. D. Shiryaev S. A. Strongin A. Y. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2007;5:737–750. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh-Stenta X. Joy J. Wang S. F. Kwek P. Z. Wee J. L. Wan K. F. Gayen S. Chen A. S. Kang C. Lee M. A. Poulsen A. Vasudevan S. G. Hill J. Nacro K. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015;9:6389–6399. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Zhang Z. Phoo W. W. Loh Y. R. Li R. Yang H. Y. Jansson A. E. Hill J. Keller T. H. Nacro K. Luo D. Kang C. Structure. 2018;26:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidique S. Shiryaev S. A. Ratnikov B. I. Herath A. Su Y. Strongin A. Y. Cosford N. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:5773–5777. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller N. H. Pattabiraman N. Ansarah-Sobrinho C. Viswanathan P. Pierson T. C. Padmanabhan R. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3385–3393. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01508-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezgimen M. Lai H. Mueller N. H. Lee K. Cuny G. Ostrov D. A. Padmanabhan R. Antiviral Res. 2012;94:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai H. Sridhar Prasad G. Padmanabhan R. Antiviral Res. 2013;97:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian A. Manzano M. Teramoto T. Pilankatta R. Padmanabhan R. Antiviral Res. 2016;134:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomiuk D. Su X. C. Ozawa K. Bodenreider C. Lim S. P. Yin Z. Keller T. H. Beer D. Patel V. Otting G. Caflisch A. Huang D. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X. C. Ozawa K. Yagi H. Lim S. P. Wen D. Ekonomiuk D. Huang D. Keller T. H. Sonntag S. Caflisch A. Vasudevan S. G. Otting G. FEBS J. 2009;276:4244–4255. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomiuk D. Su X. C. Ozawa K. Bodenreider C. Lim S. P. Otting G. Huang D. Caflisch A. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4860–4868. doi: 10.1021/jm900448m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knehans T. Schüller A. Doan D. N. Nacro K. Hill J. Güntert P. Madhusudhan M. S. Weil T. Vasudevan S. G. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2011;25:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10822-011-9418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundermann T. R. Benzin C. V. Dražić T. Klein C. D. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;176:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pach S. Sarter T. M. Yousef R. Schaller D. Bergemann S. Arkona C. Rademann J. Nitsche C. Wolber G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:514–520. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregar-Hernandez L. Jiao G. S. Johnson A. T. Lehrer A. T. Wong T. A. Margosiak S. A. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 2011;21:209–217. doi: 10.3851/IMP1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou D. Viwanathan P. Li Y. He G. Alliston K. R. Lushington G. H. Brown-Clay J. D. Padmanabhan R. Groutas W. C. J. Comb. Chem. 2010;12:836–843. doi: 10.1021/cc100091h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravapalli S. Lai H. Teramoto T. Alliston K. R. Lushington G. H. Ferguson E. L. Padmanabhan R. Groutas W. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:4140–4148. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiew K. C. Dou D. Teramoto T. Lai H. Alliston K. R. Lushington G. H. Padmanabhan R. Groutas W. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai H. Dou D. Aravapalli S. Teramoto T. Lushington G. H. Mwania T. M. Alliston K. R. Eichhorn D. M. Padmanabhan R. Groutas W. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira A. S. Gazolla P. A. R. Oliveira A. Pereira W. L. de S. Viol L. C. Maia A. Santos E. G. da Silva I. E. P. Mendes T. A. O. da Silva A. M. Dias R. S. da Silva C. C. Polêto M. D. Teixeira R. R. de Paula S. O. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0223017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y. Huo T. Lin Y. L. Nie S. Wu F. Hua Y. Wu J. Kneubehl A. R. Vogt M. B. Rico-Hesse R. Song Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:6832–6836. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b02505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millies B. von Hammerstein F. Gellert A. Hammerschmidt S. Barthels F. Goppel U. Immerheiser M. Elgner F. Jung N. Basic M. Kersten C. Kiefer W. Bodem J. Hildt E. Windbergs M. Hellmich U. A. Schirmeister T. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:11359–11382. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinter R., Questionable Ligand Density: 6MO0, 6MO1, 6MO2, https://www.mail-archive.com/ccp4bb@jiscmail.ac.uk/msg47072.html, (accessed 01/07/2020, 2020)

- Nitsche C. Passioura T. Varava P. Mahawaththa M. C. Leuthold M. M. Klein C. D. Suga H. Otting G. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:168–174. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecher M. Li Z. Liu B. Zhang J. Koetzner C. A. Alifarag A. Jones S. A. Lin Q. Kramer L. D. Li H. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006411. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Brecher M. Deng Y. Q. Zhang J. Sakamuru S. Liu B. Huang R. Koetzner C. A. Allen C. A. Jones S. A. Chen H. Zhang N. N. Tian M. Gao F. Lin Q. Banavali N. Zhou J. Boles N. Xia M. Kramer L. D. Qin C. F. Li H. Cell Res. 2017;27:1046–1064. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Sakamuru S. Huang R. Brecher M. Koetzner C. A. Zhang J. Chen H. Qin C. F. Zhang Q. Y. Zhou J. Kramer L. D. Xia M. Li H. Antiviral Res. 2018;150:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J. Walters M. A. Nature. 2014;513:481–483. doi: 10.1038/513481a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta S. Cui T. Lam Y. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:1210–1216. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Samanta S. Cui T. Lam Y. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:1554–1560. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta S. Lim T. L. Lam Y. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:994–1001. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira A. de Souza A. P. M. de Oliveira A. S. da Silva M. L. de Oliveira F. M. Santos E. G. da Silva I. E. P. Ferreira R. S. Villela F. S. Martins F. T. Leal D. H. S. Vaz B. G. Teixeira R. R. de Paula S. O. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;149:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöne T. Grimm L. L. Sakai N. Zhang L. Hilgenfeld R. Peters T. Antiviral Res. 2017;146:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiryaev S. A. Cheltsov A. V. Gawlik K. Ratnikov B. I. Strongin A. Y. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2011;9:69–78. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A. A. Espinosa B. A. Adamek R. N. Thomas B. A. Chau J. Gonzalez E. Keppetipola N. Salzameda N. T. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;157:1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche C. Steuer C. Klein C. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:7318–7337. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platonov A. E. Shipulin G. A. Shipulina O. Y. Tyutyunnik E. N. Frolochkina T. I. Lanciotti R. S. Yazyshina S. Platonova O. V. Obukhov I. L. Zhukov A. N. Vengerov Y. Y. Pokrovskii V. I. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2001;7:128–132. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]