Abstract

Somatostatin receptor-4 (SST4) is highly expressed in brain regions affiliated with learning and memory. SST4 agonist treatment may act to mitigate Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology. An integrated approach to SST4 agonist lead optimization is presented herein. High affinity and selective agonists with biological efficacy were identified through iterative cycles of a structure-based design strategy encompassing computational methods, chemistry, and preclinical pharmacology. 1,2,4-Triazole derivatives of our previously reported hit (4) showed enhanced SST4 binding affinity, activity, and selectivity. Thirty-five compounds showed low nanomolar range SST4 binding affinity, 12 having a Ki < 1 nM. These compounds showed >500-fold affinity for SST4 as compared to SST2A. SST4 activities were consistent with the respective SST4 binding affinities (EC50 < 10 nM for 34 compounds). Compound 208 (SST4Ki = 0.7 nM; EC50 = 2.5 nM; >600-fold selectivity over SST2A) display a favorable physiochemical profile, and was advanced to learning and memory behavior evaluations in the senescence accelerated mouse-prone 8 model of AD-related cognitive decline. Chronic administration enhanced learning with i.p. dosing (1 mg kg−1) compared to vehicle. Chronic administration enhanced memory with both i.p. (0.01, 0.1, 1 mg kg−1) and oral (0.01, 10 mg kg−1) dosing compared to vehicle. This study identified a novel series of SST4 agonists with high affinity, selectivity, and biological activity that may be useful in the treatment of AD.

3,4,5-Trisubstituted-1,2,4-triazole somatostatin receptor-4 agonist SAR.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia with an estimated prevalence of 1-in-10 for those over 65 years of age.1 Approximately 40 million people globally have AD, with a projected increase to 152 million by 2050.2 There remains a lack of effective disease-modifying therapeutics to combat this disease. G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) targeting may provide a viable approach for AD treatment. Targeting of brain GPCRs has a substantial history of pharmacological success, with established processes for small molecule development and optimization.3 An exceptionally promising GPCR target for AD treatment presents itself in somatostatin (somatotropin-releasing inhibitory factor, SRIF) receptor-4 (SST4).

SRIF is a cyclic tetradecapeptide that exists in two bioactive forms, SRIF-14 (1, Fig. 1) and the N-terminally extended SRIF-28.4 Both forms are expressed throughout the mammalian body, with SRIF-14 being the predominant form in the central nervous system (CNS).5 SRIF and SRIF-containing neurons are critical mediators of synaptic plasticity, altering synaptic transmission and neuronal activity.6,7 Considerable evidence supports SRIF involvement in learning and memory.8,9 In animal studies, SRIF administration has shown to enhance learning,10,11 while loss of SRIF impairs memory.12–14 SRIF also has tangible disease modifying attributes. SRIF is a positive regulator of neprilysin,15 a primary amyloid-beta (Aβ)-degrading enzyme in the brain.16 Accumulation of Aβ in the brain is a hallmark of AD and contributor to neurodegeneration and dementia.17 The gradual decline of brain SRIF levels in AD has been hypothesized to afford a decrease in neprilysin activity, with a corresponding elevation of Aβ levels.15,16 Furthermore, neprilysin can degrade toxic soluble Aβ42 oligomers.18,19 Soluble oligomers more closely correlate with synaptic loss, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia than insoluble Aβ plaques.17,20 In AD models, SRIF treatment has shown to increase neuronal neprilysin activity and synaptic localization, decreasing brain Aβ42 levels.15 Enhancing neprilysin activity has further shown to protect neurons from Aβ toxicity,21 as well as reverse memory deficits in mice.22 The cognitive enhancing and disease modifying actions of SRIF support the targeting of its receptors for AD therapeutic development.16,23

Fig. 1. Structures of SST-14 (1) and NNC 26-9100 (2).

The five human SRIF receptors (SST1–5) are categorized into two families (SRIF-1 family: SST2, SST3, SST5; SRIF-2 family: SST1, SST4).24 All SSTs are Gi/Go GPCR proteins sensitive to pertussis toxin, with the capacity to induce a number of signaling cascades upon activation. Each receptor subtype binds SRIF with high affinity, yet can be distinguished by structure, function, tissue distribution, and pharmacological selectivity. Of the respective subtypes identified within the brain, SST4 has several key advantages. Firstly, SST4 is highly expressed in neurons of the neocortex and hippocampus.5,25 These major learning and memory centers of the brain are heavily affected by elevated Aβ levels in AD.17 This helps maximize potential therapeutic actions to primary tissues affiliated with AD neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. Secondly, SST4 has limited peripheral distribution and pituitary expression,26 with selective SST4 agonist treatment showing no effect on glucagon, growth hormone, or insulin release.27 This restricted expression reduces the likelihood of substantial off-target effects. Thirdly, SST4 has a low level of receptor internalization and a rapid rate of receptor recycling following agonist treatment.24,28 This supports SST4 as a sustainable pharmacological target.

SST4 agonist actions have been validated in mouse models of AD. We performed proof-of-concept evaluations using NNC 26-9100 (2, Fig. 2), the first reported enzymatically-stable non-peptide agonist with high affinity and selectivity at SST4.29,30 Chronic NNC 26-9100 treatment dose-dependently improved memory with a reduction of cortical tissue Aβ42 expression in the senescence accelerated mouse-prone 8 (SAMP8) model of AD-related cognitive decline.31 Single-dose administration enhanced learning and memory, with an associated increase in cortical neprilysin activity.32 The learning enhancement and reduction of Aβ42 expression were reversed with neprilysin inhibition.33 The effect on neprilysin was substantiated in 3xTg-AD mice, with NNC 26-9100 increasing cortical neprilysin mRNA expression by 9.3-fold.34 Moreover, NNC 26-9100 decreased the expression of the Aβ42 trimers in the brains of both SAMP8 and Tg2576 mice (overexpressing human APP). Aβ trimers appear to be the most abundant oligomeric form produced and secreted by neurons.35 The Aβ trimers have been proposed as the “molecular brick” for non-fibrillary Aβ assemblies,20 associated with the disruption of axonal transport36 and deficits in long-term potentiation.37,38

Fig. 2. 1,2,4-Triazole nucleus (3) and lead 1,2,4-triazole 4.

Independent investigations provide further support and rationale for SST4 targeting. In a study by Yu et al., the overexpression of the postsynaptic density protein-93 in APPswe/PS1dE9 mice upregulated SST4 with a corresponding hippocampal increase in neprilysin expression, reduction of Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, and attenuation of memory deficits.39 In an evaluation of non-AD model mice, SST4 agonist administration dose-dependently enhanced striatal-dependent memory formation.40 There is also the growing recognition that early AD neuronal network dysfunction and hyperactivation are linked to seizures.41,42 Not only has SRIF long been identified to inhibit seizure activity,43,44 but the SRIF decline in AD aligns with seizure development.23,45 SST4 has shown to mediate anti-seizure effects in mice.44,46 Finally, SST4 agonist and mouse knock-out evaluations identify anti-anxiety,47–49 anti-depressant,47–49 and analgesic50–52 effects, which could provide complementary benefits in AD populations.

Although NNC 26-9100 provided proof-of-concept validation towards AD treatment, as a thiourea-containing compound it has liabilities. Thioureas can form reactive oxidation products, generated by flavin monooxygenase (FMO) or cytochrome P450, implicated in thyroid depression, pulmonary edema, and liver necrosis.53,54 In redirecting our SST4 agonist development program, we focused on the known structure–activity relationship (SAR). Firstly, Trp8 and Lys9 within the β-turn of SRIF-14 have been identified as essential for binding to all SSTs.26 The Lys9 has been reported to interact with the aspartic acid in transmembrane helix 3.55,56 Secondly, alanine scanning studies identified Phe6 as necessary for binding at SST4.57 We advanced the 1,2,4-triazole nucleus (3, Fig. 2) as an alternative scaffold.58 This nucleus has a cis-amide bond isostere found in natural peptides and is resistant to peptidase activity. Moreover, it provides three points of diversity via substitutions at 3, 4, and 5-position, thus providing the scaffold for mimicking Phe6, Trp8, and Lys9. Incorporation of our previously established SAR29,30 into the 1,2,4-triazole nucleus led to compound 4 (Fig. 2), which demonstrated high affinity for SST4 (19 nM) with at least 240-fold selectivity over all other SST receptors, and full agonist activity (EC50 = 6.5 nM).58 Employing our model-built SST4 structure,59 docking studies showed compound 4 forms key interactions with Asp90, His258, Trp171, and Gln243.58

Herein, we report the SAR studies of 3,4,5-trisubstituted-1,2,4-triazoles based on our structural lead (4), towards development of a SST4 new chemical entity for AD treatment. Synthetic efforts were coupled with structure-guided design and information stemming from earlier scaffolds with an added focus on physicochemical profiling for oral bioavailability. Synthetic campaigns explored side-chain mimetics of Phe6/Phe7, Trp8, and Lys9 on the 1,2,4-triazole nucleus such as amine-linkers replacing the imidazole ring, various substituents on the 5-benzyl and/or alternative moieties to benzyl, one- vs. two carbon-linkers to 3-indolyl, and substituents on the indole. Research culminated in a number of high affinity SST4 agonists, twelve of which show sub-nanomolar binding affinity and activity, and more than 100-fold selectivity across all SST receptors. Compound 208 was advanced for memory testing in a mouse model of AD-related cognitive decline, showing memory enhancement with both i.p. and oral administration.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

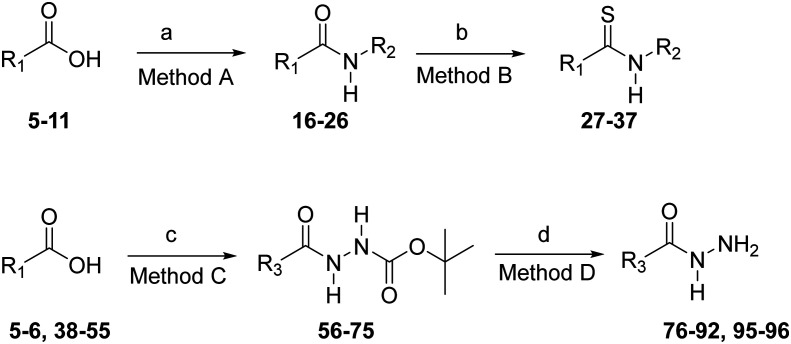

Required amides 16–26 (Scheme 1) were synthesized from carboxylic acids 5–11 and amines 12–15 using a standard 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)-1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) coupling procedure. Thioamides 27–37, necessary for the construction of the 1,2,4-triazole nucleus, were synthesized from amides 16–26 under anhydrous conditions using Lawesson's reagent (Scheme 1). Acyl hydrazides 56–75 (Scheme 1) were prepared from carboxylic acids 5–6, 38–55 and tert-butyl carbazate (Boc-hydrazine) using EDC-HOBt coupling conditions. Deprotection of the tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)-protecting group from 56–75 was accomplished with ethanolic–hydrogen chloride to yield pure hydrazides 76–92, 95 after basification with triethylamine. 1,2,4-Triazoles 97–151 (Scheme 2) bearing an 3-(imidazol-4-yl)propyl group at the 4-position were conveniently prepared from thioamides 31–37 and hydrazides 76–92, 95 as previously described.58 The reaction proceeds through an intermediate acylamidrazone in which cyclization to the trityl-protected-1,2,4-triazoles 97–151 is facilitated by the use of silver benzoate as the thiophile. Removal of the N-trityl group at the 1-position on the imidazole ring using 2 N HCl in ethanol gave the desired 1,2,4-triazoles 158–212 (Scheme 2). 1,2,4-Triazoles lacking substitution at the 5-position (156 and 157) were synthesized as shown in Scheme 3. First, reaction of the trityl-protected isothiocyanate 152 (ref. 60) with hydrazides 95 and 153 gave intermediate acyl thiosemicarbazides, which were cyclized to the 3-thiol-1,2,4-triazoles 154 and 155 with 2 N NaOH. The resulting 3-thiol-1,2,4-triazoles were oxidized with peracetic acid to yield the trityl-protected 1,2,4-triazoles 156 and 157. Deprotection of the trityl groups with 1 N HCl gave the 3,4-disubstituted-1,2,4-triazoles 213 and 214. The Boc-protected-1,2,4-triazoles 215–217 were prepared from thioamides 28–30 and 3,4-dichlorophenyl acetohydrazide 96 (ref. 58) (Scheme 4). Removal of the Boc-protecting group under acidic conditions gave the desired 4-aminoalkyl-1,2,4-triazoles 218–220.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of amides 16–26, thioamides 27–37, and hydrazides 76–92 and 95–96. Reagents and conditions: a) EDC·HCl, HOBt·H2O, R2NH2 (12–15), DMF; b) Lawesson's reagent, THF; c) EDC·HCl, HOBt·H2O, H2NNH-Boc, Et3N, DMF; d) i. CH2Cl2, 4 N HCl, dioxane, ii. CH2Cl2, Et3N.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 4-(imidazol-4-yl)propyl-1,2,4-triazoles 158–212. Reagents and conditions: a) i. AgOBz, AcOH, CH2Cl2; ii. 1 : 1 MeOH–CH2Cl2, 1 N HCl, iii. DIEA; b) i. EtOH, 2 N HCl, 70° C, 2–4 h; ii. 2 N NaOH.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted-1,2,4-triazoles 156–157. Reagents and conditions: a) i. DIEA, DMF, 70 °C, ii. 2 N–NaOH, EtOH, 50 °C; b) i. CH2Cl2, H2O2, HOAc, ii. 4 N NaOH; c) 2 N HCl–EtOH, 70 °C, 2 h.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of 4-aminoalkyl-1,2,4-triazoles 218–220. Reagents and conditions: a) i. AgOBz, AcOH, CH2Cl2; b) i. 1 : 1 MeOH–HCl, ii. iPr2NH; c) i. CH2Cl2, 4 N HCl-dioxane, ii. CH2Cl2, Et3N.

SAR of 4-(aminoalkyl)-5-benzyl-substituted-1,2,4-triazoles

As our initial work identified the (imidazol-4-yl)propyl group (Lys9-mimetic) at position-4 greatly enhanced SST4 affinity and selectivity,58 we first evaluated the impact of imidazole replacement with an amine group with different chain lengths (Table 1). In earlier studies, the 4-(3-aminopropyl)-1,2,4-triazole 221 showed limited affinity for SST4 (Ki = 2380 nM).58 Consequently, we investigated the effect of an aminoalkyl group at the 4-position of the 1,2,4-triazole scaffold with aminoethyl 218, aminobutyl 219, and aminopentyl 220 derivatives. The aminobutyl analogue 219 (Ki = 653.4 nM) showed the highest affinity at SST4 in this series. Extending the alkyl chain to 5 carbons (compound 220) or reducing it to 2 carbons (compound 218) resulted in decreased affinity at SST4. In our docking experiments with the model-built SST4 structure, the aminobutyl derivative 219, which is the best among the amine-derivatives, is predicted to form a hydrogen bond with Asp90.59 However, for this ionic bond to be formed, a reverse orientation is predicted with the dichloro-benzyl positioned in the proximity of Gln243, but not close enough to interact with the sp2-hybridized oxygen of glutamine. Indole does not form any interactions, while the triazole is maintaining the hydrogen-bonding interactions with the side chain of His258 and backbone of Trp171 (Fig. 3a). We hypothesize that the dichloro-benzyl enters the binding pocket first, and thus it is observed deeper in the pocket. In regards to 220 (Fig. 3b), the binding poses have either an energetically unfavorable conformation or when an ionic interaction with Asp90 is observed, all other bonding interactions in the ligand–receptor complex are lost, and the ligand is not as deep into the pocket. Similarly, 218 loses all other interactions when a hydrogen bond is formed with Asp90, because the methylene linker is not long enough for the formation of the ionic bond, pushing the triazole away from His258 and Trp171 (Fig. 3c). These results strongly support the central role of an (imidazol-4-yl)propyl group at position-4 on the triazole ring in enhancing SST4 affinity and selectivity.

Evaluation of 4-aminoalkyl-1,2,4-triazoles, chain length assessment.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound # | R | Binding affinity | Activity | ||||

| Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | ||||||

| SST1 | SST2A | SST3 | SST4 | SST5 | SST4 | ||

| 218 | (CH2)2NH2 | — | >10 000 | — | >10 000 | — | — |

| 221 a | (CH2)3NH2 | — | >10 000 | — | 2380a | — | — |

| 219 | (CH2)4NH2 | — | >10 000 | — | 653.4 | — | 1065 |

| 220 | (CH2)5NH2 | — | >10 000 | — | 3224 | — | — |

Ref. 58

Fig. 3. Binding modes of 219 (panel a), 218 (panel c), and two poses of 220 (panel b) representing energetically unfavorable conformations.

SAR of 3-(indol-3-yl)ethyl-5-benzyl-substituted-1,2,4-triazoles

We next evaluated the importance of the 5-benzyl and its substituents, while maintaining the (indol-3-yl)ethyl group at position-3 and the (imidazol-4-yl)propyl group at position-4 of the 1,2,4-triazole ring (Table 2). Compared to the structural lead 4 (Ki = 19.8 nM), complete removal of the 5-benzyl (179, Ki = 827.6 nM) resulted in a substantial reduction in SST4 binding affinity, thus confirming the need of a Phe6/Phe7 mimetic group of SST-14. In contrast, removal of the 3,4-dichloro groups from 4 resulted in no significant shift in SST4 binding affinity (158, Ki = 12.0 nM). Whereas, varying the positions of the 3,4-dichloro groups to 3,5-dichloro (165, Ki = 51.7) resulted in an almost 2-fold reduction in SST4 binding affinity, while the 3,5-difluoro (160, Ki = 16.2) showed no substantial SST4 affinity change compared to 4. Both 158 (Fig. 4a) and 165 (Fig. 4b) maintain the same bonding pattern; however, they slightly differ in the orientation of the benzyl ring. Specifically, in both ligand–SST4 predicted complexes, the indole is hydrogen bonding with Gln243, imidazole forms a hydrogen bond with Asp90, and aryl–aryl interactions are predicted between indole and Trp171, His258, and Phe239. The dichloro-benzyl in 165 forms a cation–π interaction with Arg74, and is pointing towards Val256, but is not within an acceptable distance for any hydrophobic interactions. However, the benzyl group of 158 is tilted towards a pocket formed by lipophilic residues Val256, Val259, and Ala 71. Further, in elucidating the importance of the benzyl ring, we compared the 179-SST4 predicted complex against the 4-SST4 docked structure. Whereas the dichloro-benzyl in compound 4 is surrounded by Ala170, His168, Ala71, and forming a halogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Ser70, these interactions are not seen with 179, which also lacks the hydrogen bond between Gln243 and indole (Fig. 4c). In summary, these findings indicate that both the position and the size of halogen replacement impact SST4 binding affinity.

Modification of 5-position phenyl of 1,2,4-triazole ring.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound # | X | R | Binding affinity | Activity | ||||

| Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | |||||||

| SST1 | SST2A | SST3 | SST4 | SST5 | SST4 | |||

| 179 | — | — | — | >10 000 | — | 827.6 | — | — |

| 158 | H | H | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 12.0 | >10 000 | 16.5 |

| 4 a | 3,4-Cl2 | H | 4750 | >10 000 | 6628 | 19.8 | >10 000 | 6.8 |

| 165 | 3,5-Cl2 | H | — | 6975 | — | 51.7 | — | 17.0 |

| 160 | 3,5-F2 | H | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 16.2 | >10 000 | 8.8 |

| 161 | 2-Cl | H | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 21.5 | >10 000 | 17.3 |

| 162 | 3-Cl | H | 6929 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 5.1 | >10 000 | 7.3 |

| 163 | 4-Cl | H | — | >10 000 | — | 37.5 | — | 19.3 |

| 159 | 3-F | H | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 12.4 | >10 000 | 21.0 |

| 166 | 3-Br | H | 4744 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 5.5 | >10 000 | 4.4 |

| 167 | 3-CF3 | H | 5309 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 3.2 | >10 000 | 6.1 |

| 169 | 3-CN | H | — | >10 000 | — | 30.3 | — | 75.8 |

| 170 | 3-NO2 | H | — | >10 000 | — | 36.6 | — | 98.4 |

| 171 | 2-OCH3 | H | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 39.5 | >10 000 | 28.9 |

| 172 | 3-OCH3 | H | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 7.7 | >10 000 | 15.6 |

| 173 | 4-OCH3 | H | — | >10 000 | — | 267.2 | — | — |

| 174 | 3-OCF3 | H | 4076 | >10 000 | — | 14.9 | — | 55.0 |

| 175 | 3-OBn | H | — | >10 000 | — | 386.6 | — | 254.5 |

| 176 | 3-SO2CH3 | H | 3653 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 7.0 | >10 000 | 22.7 |

| 177 | 4-C6H5 | H | — | >10 000 | — | 945.3 | — | — |

| 164 | 3,4-Cl2 | CH3 | 3172 | >10 000 | 6989 | 40.4 | >10 000 | 21.3 |

| 168 | 3-CF3 | CH3 | 2236 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 11.0 | >10 000 | 10.7 |

Ref. 58

Fig. 4. Binding poses of 158 (a, orange), 165 (b, yellow), and 179 (c, green). Compounds in panels a and b are shown to hydrogen-bond with both Asp90 and Gln243, whereas panel c shows limited interactions with critical amino acids in the binding pocket.

A series of mono-chloro derivatives 161–163 were then evaluated. The 3-Cl analogue 162 showed the highest affinity at SST4 (Ki = 5.1 nM), an almost 4-fold enhancement in binding affinity over 4. Compared to 162, the 2-Cl derivative 161 (Ki = 21.5 nM) and the 4-Cl 163 (Ki = 37.5) demonstrated about 4-fold and 7-fold reduced SST4 affinity, respectively. The importance of the meta-Cl substitution on the 5-benzyl group is supported by our homology model,59 wherein the meta-Cl group formed a halogen bond with the carbonyl group of Ser70. Interestingly, while the para-Cl comparatively reduces SST4 binding affinity (163), addition of a 3-Cl group appears to offset this decrease in binding affinity (4). Docking experiments indicate that the chlorine in 162 makes a better halogen bond interaction with Ser70 than the 3,4-dichloro substitution in 4 in regards to angle and distance. However, it should be noted that scoring functions are not as sensitive to relatively small changes in binding affinity, and therefore our predicted complexes for 162 and 4 should be considered with caution (Fig. 5a). Finally, the presence of lipophilic and/or strong electron withdrawing groups in the meta-position of the 5-benzyl substituent enhanced binding affinity at SST4. Replacement of the 3-Cl with either a 3-Br (166, Ki = 5.5 nM) or 3-CF3 (167, Ki = 3.2 nM) showed relatively similar SST4 binding affinities, further substantiating this finding.

Fig. 5. Overlays of 162 in orange and 4 in yellow (panel a), 162 in orange and 172 in yellow (panel b), 173 and 172 in orange and yellow, respectively, (panel c), and 173 (orange), 163 (yellow) and 177 (green) in d.

We next evaluated the effect of polar, electron withdrawing substituents. When 3-CN (169, Ki = 30.3 nM) and 3-NO2 (170, Ki = 36.6 nM) were introduced, SST4 affinity decreased by about 3-fold compared to unsubstituted 158. A series of methoxy-substituted derivatives 171–173 were also investigated. The 3-OCH3 (172, Ki = 7.7 nM) did not substantially change SST4 binding affinity when compared to the 3-Cl (162), thus suggesting the meta position can accommodate either a halogen or a methoxy without impact on affinity. In comparing 162-SST4 and 172-SST4 docked complexes (3-Cl versus 3-OCH3 substituted derivatives), a bidentate interaction is formed between imidazole and indole with Asp90, whereas the indole is positioned in a hydrophobic pocket consisting of Phe239, Trp171, and His258. Further, the C–Cl bond of 162 is parallel rather than orthogonal to the amide plane of Val256, in agreement with previous reports,61 while the meta-methoxy of 172 hydrogen-bonding with Thr255 and also forming a hydrophobic interaction with Val256 (Fig. 5b). However, the 2-OCH3 (171Ki = 39.5) and the 4-OCH3 (173, Ki = 267.2 nM) showed about a 2-fold and 7-fold reduction, compared to respective Cl analogues (161, 163). Apparently, a strong electron donating group in either the ortho- or the para-position of the 5-benzyl substituent is unfavorable for SST4 binding. Contrary to the bidentate interaction of both the indole and imidazole with Asp90, as noted for 172 above, 173 assumes the alternative binding pose we have observed with these compounds, where the indole is hydrogen bonding with Gln243 and the imidazole interacts with Asp90. However, none of the interactions predicted for the methoxy in 172 are seen in 173. In the latter, the methoxy is pointing towards the solvent which could form a hydrogen-bond with a nearby water but overall the orientation is not optimal for the alkyl otherwise (Fig. 5c).

Group size respective to the para-position impacts binding. Although the para-position can accommodate modestly sized groups, such as Cl (163) and OCH3 (173), a dramatic reduction in binding affinity occurs with a phenyl ring in this position (177, Ki = 945.3 nM). Further exploring the meta-position, we introduced a methyl sulfone group (176, Ki = 7.0 nM), resulting in high binding affinity at SST4. Although the meta-position of the 5-benzyl substituent is sterically less restricted, a large meta-benzyloxy group (175, Ki = 386.6 nM) dramatically decreases binding affinity at SST4. This is confirmed by docking experiments as well. For 177, we observe the same as with 175 in that the additional phenyl substituent leads to a heavy hydrophobic moiety which enters the binding pocket first, thus placing the indole towards the solvent. In turn, interactions with Gln243 are lost, but the diphenyl is in a hydrophobic pocket consisting of Phe239, Tyr240, Thr175 and Val176. In contrast, 163 maintains interactions with Asp90, Trp171, Gln243, His258 but also forms a halogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen of Arg74 in an almost linear geometry; a multipolar interaction is also observed between the halogen and the plane of the amide bond of His75 (Fig. 5d).

An evaluation of the indole nitrogen was also performed. Substitution of a methyl group on the indole ring nitrogen resulted in a moderate decrease in SST4 binding affinity (compound 164, Ki = 40.4 nM) compared to non-methylated (4, Ki = 19.8 nM). This decreased affinity associated was consistent regardless of 5-benzyl group substituent, as shown with the 3-CF3 5-benzyl compounds (methylated-indole 168, Ki = 11.0 nM vs. non-methylated-indole 167, Ki = 5.0 nM). This observation is consistent with the findings in the earlier docking studies using Glide.59 The indole N–H was shown to hydrogen bond with Gln243 using our previously generated homology model.59 This strongly suggests that substitution on the indole nitrogen removes a site of hydrogen bonding at the active site of SST4.

SAR of 3-(indol-3-yl)methyl-5-benzyl-substituted-1,2,4-triazoles

We next assessed the 2-C (Table 2) vs. the 1-C link (Table 3) to the 3-position of the indole ring with matched modifications to the 5-benzyl. Removal of the 5-benzyl allowed a direct comparison between the 1-C (213, Ki = 99.4 nM) and 2-C (179, Ki = 827.6 nM) linkers to indole with the first displaying substantially higher SST4 binding affinity. In comparing the docked complexes of SST4-213 and SST4-179, the additional methylene of 179 in the linker positions the indole too far from Gln243 to form a hydrogen bond. Further, the predicted binding mode for 179 is 9th-ranked, while the one for 213 is 2nd. Because we wanted to ensure that there is no inherent bias, as indicated in our methods, several poses were generated for each of the synthetic targets during the docking experiments. Regarding the remaining poses of 179, the only other which could be viable predicts a binding mode translated towards transmembrane helices 1, 2 and 7, which in turn result in hydrogen bonding of the imidazole with Asp90, however, no other interactions are observed besides His258 (Fig. 6). In contrast, 213 maintains all interactions in accord with aforementioned bioactive conformations of high-affinity synthetic targets. In all cases, regardless of ortho-, para-, or meta-positioning or group substitution on the 5-benzyl, there was an improved SST4 binding affinity with the 1-C link to the 3-indolyl group respective to the corresponding 2-C linked compound. Improved SST4 affinity ranged from 3.8- to 120-fold, with the greatest enhancement shown with the para-methoxy group (202, Ki = 2.2 nM, vs.173, Ki = 267.2 nM). We conclude, the shorter chain between the indole ring and the 1,2,4-triazole nucleus does not orient the 5-benzyl group in a sterically restricted region of the active site of SST4. Such that the 1-C linker imparts an overall more favorable receptor interaction.

Impact of 1-C linker to the indole, identifying SAR contributions.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound # | X | Binding affinity | Activity | ||||

| Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | ||||||

| SST1 | SST2A | SST3 | SST4 | SST5 | SST4 | ||

| 213 | — | — | >10 000 | — | 99.4 | — | 401.9 |

| 180 | H | 1518 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 1.7 | >10 000 | 2.0 |

| 190 | 3,4-Cl2 | — | 3697 | — | 0.8 | — | 0.3 |

| 192 | 3,5-Cl2 | — | 5111 | — | 1.2 | — | 1.3 |

| 186 | 2-Cl | — | >10 000 | — | 2.6 | — | 3.1 |

| 187 | 3-Cl | 1235 | 4000 | 4398 | 0.5 | >10 000 | 0.1 |

| 189 | 4-Cl | 624.4 | 7693 | 4072 | 1.4 | >10 000 | 1.3 |

| 183 | 4-F | 1156 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 1.7 | >10 000 | 1.8 |

| 198 | 2-OCH3 | — | 6303 | — | 0.7 | — | 1.9 |

| 200 | 3-OCH3 | — | 9185 | — | 0.5 | — | 0.5 |

| 202 | 4-OCH3 | 2576 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 2.2 | >10 000 | 7.3 |

| 195 | 3-CF3 | 587.6 | >10 000 | 2335 | 0.8 | >10 000 | 0.6 |

| 205 | 3-CN | — | >10 000 | — | 7.1 | — | 10.7 |

| 207 | 3-SO2CH3 | 660.7 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 1.0 | >10 000 | 3.3 |

| 209 | 4-SO2CH3 | — | >10 000 | — | 58.8 | — | 169.2 |

Fig. 6. Two putative poses of 179 indicative of the reverse positioning of the indole substituent in order to have the imidazole within hydrogen-bonding distance from Asp90.

Because the 1-C linkers to indole are preferable to 2-C, we proceeded to evaluate the impact of two specific substituents (fluoro and methoxy) on indole, while substituents on the 5-benzyl were the same as those explored in previous SAR (Table 4). This allowed us a side-by-side comparison and provided an understanding on whether substitutions on indole are critical for binding affinity while further refining physiochemical characteristics towards brain targeting. The choice of the 6-F was made given its capacity to enhance metabolic stability of the indole. The 5-OCH3 substituent was made to enhance overall polarity and solubility. Overall, it appears that neither the 6-F or 5-OCH3 indolyl substitutions have a pronounced effect on SST4 binding affinity (see Tables 3 and 4). However, when the 6-F was maintained but the 5-benzyl group was replaced with a neopentyl substituent, the SST4 binding affinity was substantially reduced (211, Ki = 57.1 nM, compared to (180, Ki = 1.7 nM). This further supports the 5-benzyl group on the 1,2,4-triazole ring makes an important lipophilic interaction with the active site of SST4. Another change we investigated, in conjunction with the two substitutions on indole, was to replace the benzyl with a (6-fluoroindol-3-yl))methyl group (212). While compound 212 showed similar SST4 affinity (Ki = 0.7 nM) as the unsubstituted 5-benzyl analogue 180 (Ki = 1.7 nM), the SST4 selectivity of 212 to other SST receptors was diminished (SST1Ki = 97.8 nM, SST2Ki = 639.7 nM). It seems in both cases that the indolyl is deeper into the pocket; however the halogen does not contribute to additional bonding interactions whereas poses in which the indolyl is pointing towards the solvent seem to lack most main interactions observed with the high-affinity structures. Once again, even though scoring functions are far from being accurate, it is worth noting that there is a 0.3 kcal per mole difference in the docking score favoring 180.

Effect of indole ring substitution and variation of electronic substituent effects.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound # | Y | X | Binding affinity | Activity | ||||

| Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | |||||||

| SST1 | SST2A | SST3 | SST4 | SST5 | SST4 | |||

| 214 | — | — | — | >10 000 | — | 717.3 | — | 1036 |

| 181 | 6-F | H | 1825 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 3.0 | >10 000 | 2.8 |

| 191 | 6-F | 3,4-Cl2 | 872.6 | 1104 | 1557 | 1.1 | >10 000 | 1.0 |

| 193 | 6-F | 3,5-Cl2 | — | 4862 | — | 1.7 | — | 2.2 |

| 188 | 6-F | 3-Cl | — | 1734 | — | 0.5 | — | 0.8 |

| 184 | 6-F | 4-F | 468.0 | 3969 | >10 000 | 0.9 | >10 000 | 3.2 |

| 194 | 6-F | 3-Br | 263.5 | 2080 | 2733 | 1.0 | >10 000 | 0.3 |

| 196 | 6-F | 3-CF3 | 543.6 | 3278 | 1613 | 0.7 | 6526 | 0.2 |

| 206 | 6-F | 3-CN | — | 5884 | — | 6.9 | — | 7.2 |

| 199 | 6-F | 2-OCH3 | — | 5115 | — | 0.9 | — | 0.2 |

| 201 | 6-F | 3-OCH3 | 971.1 | 5605 | 5404 | 0.6 | >10 000 | 0.7 |

| 203 | 6-F | 4-OCH3 | 1080 | 5304 | >10 000 | 5.1 | >10 000 | 6.7 |

| 208 | 6-F | 3-SO2CH3 | 443.2 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 0.7 | >10 000 | 2.5 |

| 210 | 6-F | 4-SO2CH3 | — | >10 000 | — | 80.8 | — | 846.9 |

| 211 | — | — | 4336 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 57.1 | >10 000 | 77.7 |

| 212 | — | — | 97.8 | 639.7 | 1736 | 0.7 | 9335 | 0.7 |

| 182 | 5-OCH3 | H | 1716 | 7103 | >10 000 | 3.1 | >10 000 | 6.0 |

| 185 | 5-OCH3 | 4-F | 1032 | 5434 | >10 000 | 2.8 | >10 000 | 6.0 |

| 197 | 5-OCH3 | 3-CF3 | 365.3 | 1693 | 1129 | 1.8 | >10 000 | 1.0 |

| 204 | 5-OCH3 | 4-OCH3 | 1011 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 3.3 | >10 000 | 5.6 |

In vitro functional assay

Functional activity for all compounds with a SST4 binding Ki < 100 nM was determined by way of the forskolin-stimulated inhibition of cAMP assay, using recombinant Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells expressing SST4.60 SST4 activity consistently correlated with the SST4 binding affinity determinations, especially for those compounds with high SST4 affinity. All tested compounds identified as agonists.

Selectivity profile

All compounds were also evaluated against SST2A, representing the SRIF1 receptor family. Compounds with SST4Ki < 100 nM all showed 500-fold or higher affinity compared to SST2A. Select compounds were then evaluated for SST1, SST3, and SST5 affinity. As SRIF2 family members, SST3 and SST5 showed no appreciable affinity for any assessed compounds. Only compound 212 showed a SST1 binding affinity <100 nM; however, 212 still has 137-fold higher affinity for SST4.

Off-target binding of compound 4, 208, 211, 212, and 214 against 46 off-target receptors (Table S1†), performed by the National Institute of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PSPD).62 The primary screen evaluated inhibition of ligand binding at 10 μM of compounds at respective receptors, and if the compound exhibited >50% inhibition it was run to determine Ki. The di-indolyl containing compound 212 showed a >50% inhibition on 22 off-target receptors; however upon full screen most Ki values were in the micromolar range. Compounds 4, 208, 211, 212, and 214 showed very few off-target receptors with >50% inhibition, with subsequently run Ki values mostly in the micromolar range. This further supports a relatively high degree of selectivity of our 3,4,5-trisubstituted-1,2,4-triazole compounds for SST4.

QSAR modeling and rationale for advancing a lead

Given the internal collection of SST4 agonists, we explored plausible correlations between structures and Ki by constructing a predictive QSAR model to rank order designed synthetic targets. Towards this end, 89 compounds including the ones in the present study (Tables 1–4), along with those reported in our earlier published works58,59 consisted the training and test sets, while patented SST4 (ref. 63 and 64) along with internal compounds (unpublished results) were employed as the validation set (total 39). The Q2 is higher than 0.7, while typically a Q2 > 0.5 for the validation set is indicative of a very good model. Results for the average Ki and pKi predictions for each compound in the training, test and validation sets are presented in Table S2,† whereas the scatterplot is shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen that the predicted pKi values are very close to the observed.

Fig. 7. Predicted and observed affinities for training set (blue) and test set (red) compounds using DKPLS models constructed from radial fingerprints.

As blood–brain barrier permeability is the primary prerequisite for CNS penetration, molecular weight (MW), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), polar surface area (PSA), and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux were evaluated towards next stage consideration (Table S3†). The physiochemical indicators are not absolute filters, rather guided development respective to compound profiles taken as a whole. Compounds met an acceptable MW range (306 to 516 Da) and fit the criteria for the number of HBD (≤2) and HBA (≤5) with few exceptions. Most of compounds also met a <90 Å2 PSA criteria.65 Given initial lead compound 4 identified a relatively high efflux ratio (26.9), particular emphasis was placed on this component. Only the nitrile substitution (169) substantially reduced the efflux ratio respective to the compounds with 2-carbon linker to 3-indolyl group. The 1-carbon vs. 2-carbon linker to the 3-indolyl group (compounds 158vs.180; 167vs.195) did not identify any appreciable impact on the efflux ratio. Only the methylsulfonyl containing compounds (176, 207–209) exhibited efflux ratios <5. The methylsulfonyl substituent further reduced clog P (<2) towards enhanced solubility.

Learning and memory evaluation

Compound 208 exhibited high SST4 binding affinity (Ki = 0.7 nM), activity (EC50 = 2.5 nM), and selectively (>600-fold over all other SSTs), with viable efflux ratio (2.5), and the 6-F substitution on the 3-indolyl helping to reduce metabolism. Compound 208 was advanced to T-maze learning and memory testing in the SAMP8 model of AD-related cognitive decline. The SAMP8 model presents age-dependent behavioral, morphological, and neurochemical changes identified with late-onset AD.66,67 T-maze assesses spatial learning and memory affiliated with hippocampal function,68,69 effective for tracking progression of neurodegenerative pathology and therapeutic interventions in AD mouse models.31–33,70,71 Compound 208 was administered i.p. and oral, respectively, with daily dosing over a period of 28 days (Fig. 8). The mean trials to first avoidance represents acquisition learning, the retention of the learned task (1 week later, day 28) was reported as the mean trails to criterion. The acquisition of new information occurred only with i.p. administration, reaching significance at 1 mg kg−1 dose. Memory retention was shown for both i.p. (0.01–1.0 mg kg−1) and oral (0.01 and 10 mg kg−1) administration. An oral dose of 10 mg kg−1 is still in the relatively low range for oral administration. Response differences between i.p. and oral dosing would implicate absorption and/or distribution impact with oral route.

Fig. 8. Compound 208 chronic administration learning and memory evaluations. T-maze acquisition learning (21 days per daily treatment) with i.p. (A) and oral (B) administration, and retention memory (28 days per daily treatment) with i.p. (C) and oral (D) administration in 12 month old SAMP8 mice (n = 9–11/group). One-way ANOVA, with Dunnett's post hoc, compare to vehicle (0 mg kg−1). Value are mean ± SEM. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Significance set at *p < 0.05.

Conclusions

This study substantiated the viability of the 3,4,5-trisubstituted-1,2,4-triazole nucleus for SST4 agonist development, with 59 novel compounds advanced to ligand-binding evaluations. We confirmed the importance of the 3-(imidazole-4-yl)propyl group in position 4 of the triazole ring for SST4 binding. Electron withdrawing groups in the meta-position of the 5-benzyl and 1-C linker to the 3-indolyl group significantly enhancing SST4 binding affinity. Decreasing the linker between the indole ring and the 1,2,4-triazole nucleus by one carbon atom resulted in 12 compounds with Ki values at SST4 less than 1 nM, and another 23 compounds with Ki values from 1–10 nM. The present research endeavor was enhanced by a combination of docking and QSAR modeling aiming to delineate structural requirements and tolerance at the macromolecular level. A global QSAR model was generated based on dendritic fingerprints and kernel-based partial least squares that accurately predicts experimental pKi values. The model is a guide for prioritizing future synthetic efforts. Further, comparative docking results of the SST4 agonists suggest that Asp90, Gln243, His258, and Trp171 are determining for affinity, along with hydrophobic clusters consisting of Tyr265, Phe239, Phe175 and valines 256, 259. Our optimization program led to the high affinity and SST4 selective compound 208, shown to mitigate memory decline with chronic i.p. and oral administration in the SAMP8 model. Further enhancement of pharmacokinetic parameters, with maintenance of SST4 affinity and selectivity, may provide a viable therapeutic for the treatment of AD.

Experimental

Detailed procedures for the chemical synthesis, ligand binding, functional in vitro activity, P-glycoprotein efflux, learning and memory testing, ligand preparation and docking, and QSAR modeling are described in ESI.† All intermediates and final products were purified by re-crystallization or flash chromatography and were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, and/or HRMS. NMR spectra provided in ESI.†

Author contributions

Program oversight and funding acquisition under direction of Dr. Witt. Program conceptualization by Drs. Witt, Crider, Neumann, Kontoyianni, and Sandoval. Chemical synthesis directed by Drs. Crider and Neumann, with synthesis performed by Dr. Crider, Dr. Neumann, Shirin Mobayen, Mahsa Minaeian, Stephen Kukielski, Khush Srabony, and Rafael Frare. Ligand binding of SSTs and SST4 EC50 evaluations with associated data analyses performed by Dr. Sandoval. Computational modeling directed by Dr. Kontoyianni, with modeling performed by Dr. Kontoyianni, Dr. Hospital, and Olivia Slater. Learning and memory animal evaluations directed by Dr. Farr, with evaluations performed by Dr. Farr and Michael Niehoff. Manuscript preparation and review conducted by Drs. Neumann, Sandoval, Kontoyianni, Crider, and Witt. Correspondence respective to chemical synthesis should be directed to Dr. Crider. Correspondence respective to modeling should be directed to Dr. Kontoyianni. Correspondence respective to pharmacological evaluations should be directed to Dr. Witt.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared the following conflict of interests: Drs. Neumann, Sandoval, Kontoyianni, Hospital, Crider, and Witt are co-inventors on patent applications for the development of SST4 agonists, through Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (USA patent application No. PCT/US2018/032368; European National Application No. 18798793.8, Japanese Application No. 2019-562574). Ken Witt is CEO of Somatolynk Inc., a company focused on advancement of SST4 agonists.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG047858. We would like to thank Dr. William Kolling, Dr. Tim McPherson, and Mr. Sagar Gilda for formulation work-ups.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Table S1: Off-target actions of compounds 4, 208, 211, 212 and 214; Table S2: Predictive QSAR model to rank order designed synthetic targets; Table S3: Physicochemical properties; Table S4a–e: 95% Confidence interval information as matched to Tables 1–4 and positive control sets; Experimental methods; NMR spectra. See DOI: 10.1039/d1md00044f

References

- Alzheimer's Association Report, Alzheimers Dement, 2020, vol. 16, pp. 391–460 [Google Scholar]

- W. H. Organization, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia, (accessed Feb 2021)

- Hauser A. S. Attwood M. M. Rask-Andersen M. Schioth H. B. Gloriam D. E. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schally A. V. Chang R. C. Huang W. Y. Coy D. H. Kastin A. J. Redding T. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:3947–3951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viollet C. Lepousez G. Loudes C. Videau C. Simon A. Epelbaum J. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008;286:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artinian J. Lacaille J. C. Brain Res. Bull. 2018;141:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguz-Lecznar M. Urban-Ciecko J. Kossut M. Front. Neural Circuits. 2016;10:48. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2016.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel G. Dutar P. Epelbaum J. Viollet C. Front. Endocrinol. 2012;3:154. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedemann T. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(2952) doi: 10.3390/ijms20122952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollok I. Vecsei L. Telegdy G. Neuropeptides. 1983;3:263–270. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(83)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L. Widerlov E. Neuropeptides. 1988;12:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(88)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroutunian V. Mantin R. Campbell G. A. Tsuboyama G. K. Davis K. L. Brain Res. 1987;403:234–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettini G. Florio T. Magri G. Grimaldi M. Meucci O. Landolfi E. Marino A. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;151:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L. Alling C. Widerlov E. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1990;305:140–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T. Iwata N. Tsubuki S. Takaki Y. Takano J. Huang S. M. Suemoto T. Higuchi M. Saido T. C. Nat. Med. 2005;11:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nm1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N. Higuchi M. Saido T. C. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;108:129–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. Hardy J. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. M. Mouri A. Kokubo H. Nakajima R. Suemoto T. Higuchi M. Staufenbiel M. Noda Y. Yamaguchi H. Nabeshima T. Saido T. C. Iwata N. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:17941–17951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemitsu H. Tomiyama T. Mori H. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;350:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00898-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson M. E. Lesne S. E. J. Neurochem. 2012;120(Suppl 1):125–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Amouri S. S. Zhu H. Yu J. Gage F. H. Verma I. M. Kindy M. S. Brain Res. 2007;1152:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier R. Wolfer D. P. Welzl H. Tracy J. Galsworthy M. J. Nitsch R. M. Mohajeri M. H. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;24:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epelbaum J. Guillou J. L. Gastambide F. Hoyer D. Duron E. Viollet C. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009;89:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther T. Tulipano G. Dournaud P. Bousquet C. Csaba Z. Kreienkamp H. J. Lupp A. Korbonits M. Castano J. P. Wester H. J. Culler M. Melmed S. Schulz S. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018;70:763–835. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.015388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmer I. S. Schindler M. Humphrey P. P. Emson P. C. Neuroscience. 2000;98:523–533. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller L. N. Stidsen C. E. Hartmann B. Holst J. J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1616:1–84. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer S. P. Schaeffer J. M. J. Physiol. 2000;94:211–215. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreff M. Schulz S. Handel M. Keilhoff G. Braun H. Pereira G. Klutzny M. Schmidt H. Wolf G. Hollt V. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:3785–3797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03785.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankersen M. Crider A. M. Liu S. Ho B. Andersen H. S. Stidsen C. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:1368–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. Tang C. Ho B. Ankersen M. Stidsen C. E. Crider A. M. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4693–4705. doi: 10.1021/jm980118e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval K. E. Farr S. A. Banks W. A. Niehoff M. L. Morley J. E. Crider A. M. Witt K. A. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;654:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval K. E. Farr S. A. Banks W. A. Crider A. M. Morley J. E. Witt K. A. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012;683:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval K. E. Farr S. A. Banks W. A. Crider A. M. Morley J. E. Witt K. A. Brain Res. 2013;1520:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval K. Umbaugh D. House A. Crider A. Witt K. Neurochem. Res. 2019;44:2670–2680. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02890-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S. Koh M. T. Kotilinek L. Kayed R. Glabe C. G. Yang A. Gallagher M. Ashe K. H. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M. A. LaCroix M. Amar F. Larson M. E. Forster C. Aguzzi A. Bennett D. A. Ramsden M. Lesne S. E. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:9647–9658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;192:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M. Shankar G. M. Mehta T. Walsh D. M. Selkoe D. J. J. Physiol. 2006;572:477–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. Liu Y. Yang H. Zhu X. Cao X. Gao J. Zhao H. Xu Y. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017;59:913–927. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastambide F. Viollet C. Lepousez G. Epelbaum J. Guillou J. L. Psychopharmacology. 2009;202:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglein J. Noachtar S. McDade E. Quaid K. A. Salloway S. Ghetti B. Noble J. Berman S. Chhatwal J. Mori H. Fox N. Allegri R. Masters C. L. Buckles V. Ringman J. M. Rossor M. Schofield P. R. Sperling R. Jucker M. Laske C. Paumier K. Morris J. C. Bateman R. J. Levin J. Danek A. Neurobiol. Aging. 2019;76:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zott B. Simon M. M. Hong W. Unger F. Chen-Engerer H. J. Frosch M. P. Sakmann B. Walsh D. M. Konnerth A. Science. 2019;365:559–565. doi: 10.1126/science.aay0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binaschi A. Bregola G. Simonato M. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;14:285–301. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2003.14.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallent M. K. Qiu C. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008;286:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. Katzman R. Terry R. D. Nature. 1980;288:279–280. doi: 10.1038/288279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C. Zeyda T. Johnson B. Hochgeschwender U. de Lecea L. Tallent M. K. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3567–3576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4679-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot T. D. Gastambide F. Viollet C. Henkous N. Martel G. Epelbaum J. Beracochea D. Guillou J. L. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:1647–1656. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheich B. Cseko K. Borbely E. Abraham I. Csernus V. Gaszner B. Helyes Z. Neuroscience. 2017;346:320–336. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheich B. Gaszner B. Kormos V. Laszlo K. Adori C. Borbely E. Hajna Z. Tekus V. Bolcskei K. Abraham I. Pinter E. Szolcsanyi J. Helyes Z. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batai I. Z. Horvath A. Pinter E. Helyes Z. Pozsgai G. Front. Endocrinol. 2018;9:55. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozsgai G. Payrits M. Saghy E. Sebestyen-Batai R. Steen E. Szoke E. Sandor Z. Solymar M. Garami A. Orvos P. Talosi L. Helyes Z. Pinter E. Nitric Oxide. 2017;65:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandor K. Elekes K. Szabo A. Pinter E. Engstrom M. Wurster S. Szolcsanyi J. Helyes Z. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;539:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagg J., in Annual reports in medicinal chemistry, Elsevier, 2006, vol. 41, pp. 353–366 [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G. J. Hitchcock K. Wang Y. K. Coppola G. M. Versace R. W. Chin J. A. Shapiro M. Suwanrumpha S. Mangold B. L. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:733–741. doi: 10.1021/tx9700230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehring R. B. Meyerhof W. Richter D. DNA Cell Biol. 1995;14:939–944. doi: 10.1089/dna.1995.14.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel Y. C. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 1999;20:157–198. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis I. Bauer W. Albert R. Chandramouli N. Pless J. Weckbecker G. Bruns C. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:2334–2344. doi: 10.1021/jm021093t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daryaei I. Sandoval K. Witt K. Kontoyianni M. Michael Crider A. MedChemComm. 2018;9:2083–2090. doi: 10.1039/c8md00388b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. Crider A. M. Ansbro D. Hayes C. Kontoyianni M. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52:171–186. doi: 10.1021/ci200375j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Mealer D. Rodgers L. Sandoval K. Witt K. Stidsen C. Ankersen M. Crider A. M. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2012;9:655–662. [Google Scholar]

- Bissantz C. Kuhn B. Stahl M. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5061–5084. doi: 10.1021/jm100112j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard J. Ruda G. F. Setola V. Abecassis K. Rodriguiz R. M. Huang X. P. Norval S. Sassano M. F. Shin A. I. Webster L. A. Simeons F. R. Stojanovski L. Prat A. Seidah N. G. Constam D. B. Bickerton G. R. Read K. D. Wetsel W. C. Gilbert I. H. Roth B. L. Hopkins A. L. Nature. 2012;492:215–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro R., Ferrara M., Giovannini R. and Lindard I., Patent WO2016075239, 2016

- Giovannini R., Cui Y., Doods M., Ferrara M., Just S., Kuelzer R., Lingard I., Mazzaferro R. and Rudolf K., Patent WO2014184275, 2014

- van de Waterbeemd H. Camenisch G. Folkers G. Chretien J. R. Raevsky O. A. J. Drug Targeting. 1998;6:151–165. doi: 10.3109/10611869808997889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley J. E. Farr S. A. Kumar V. B. Armbrecht H. J. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012;18:1123–1130. doi: 10.2174/138161212799315795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomobe K. Nomura Y. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:660–669. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9923-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr S. A. Banks W. A. La Scola M. E. Flood J. F. Morley J. E. Brain Res. 2000;872:242–249. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr S. A. Banks W. A. La Scola M. E. Morley J. E. Physiol. Behav. 2002;76:531–538. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr S. A. Sandoval K. E. Niehoff M. L. Witt K. A. Kumar V. B. Morley J. E. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;54:1339–1348. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr S. A. Roesler E. Niehoff M. L. Roby D. A. McKee A. Morley J. E. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2019;68:1699–1710. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.