Abstract

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth experience high rates of victimization leading to health disparities. Community size and community climate are associated with health outcomes among SGM youth; however, we lack studies that include them as covariates alongside victimization to understand their collective impact on health. This study utilized minority stress theory to understand how community context shapes experiences of victimization and health among SGM youth. SGM youth in one Midwestern U.S. state completed an online survey (n = 201) with measures of physical health, mental health, community context, and victimization. Data were analyzed via multiple regression using a path analysis framework. Results indicate that perceived climate was associated with mental, but not physical, health; Community size was unrelated to health outcomes. Victimization mediated the association between community climate and mental health.

Keywords: depression, health, gender, LGBT issues, rural context

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth—14- to 18-year olds who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning (LGBTQ)—experience higher rates of adverse mental and physical health outcomes than heterosexual and cisgender youth (Connolly, Zervos, Barone, Johnson, & Joseph, 2016; Kann et al., 2011; Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013). SGM youth in nonmetropolitan communities are at risk of higher rates of poor outcomes than urban SGM youth and nonmetropolitan non-SGM youth (Ballard, Jameson, & Martz, 2017; Cohn & Leake, 2012; Palmer, Kosciw, & Bartkiewicz, 2012; Poon & Saewyc, 2009). Minority stress theory (MST; Meyer, 2003) contends that health disparities are the result of minority-specific stressors SGM youth face. Numerous studies illustrate that discrimination or victimization based on SGM identity contributes to higher levels of depression and suicidality among SGM youth (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, 2009; Burton, Marshal, Chisolm, Sucato, & Friedman, 2013), including nonmetropolitan youth (Ballard et al., 2017).

Nonmetropolitan communities represent complex contexts in which many SGM youth are situated. Research suggests that nonmetropolitan SGM youth experience hostility toward their SGM identities (O’Connell, Atlas, Saunders, & Philbrick, 2010; Swank, Fahs, & Frost, 2013; Yarbrough, 2003). They also report greater victimization than urban SGM youth (Ballard et al., 2017; Kosciw, Greytak, Zongrone, Clark, & Truong, 2018; Palmer et al., 2012; Poon & Saewyc, 2009). Geographic region may also affect SGM youth’s experiences such that SGM people in the Midwest and Southern U.S. are more likely than SGM youth in other regions to experience harassment and discrimination (Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danichewski, 2016). Alternatively, nonmetropolitan communities may enable strengths or resources to promote resilience. Wienke and Hill (2013) examined differences in health and happiness between nonmetropolitan and urban sexual minority adults; participants in nonmetropolitan communities reported higher levels of happiness and better perceived health. In addition, nonmetropolitan SGM youth have identified supportive aspects of their towns, challenging the dominant narrative of hostile rural communities (Paceley, Thomas, Toole, & Pavicic, 2018). These studies illustrate the importance of examining SGM youths’ communities beyond community size. For example, community climate—the support for or hostility toward SGM people in a community (Oswald, Cuthbertson, Lazarevic, & Goldberg, 2010)—is also associated with anxiety, stress, and suicide attempts among SGM people (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Woodford, Paceley, Kulick, & Hong, 2015).

To promote well-being among nonmetropolitan SGM youth, we must understand the relationships between community characteristics, victimization, and health. We lack studies illustrating the independent and shared effects of community size and climate on SGM youths’ health. In addition, the relationship between community climate and youths’ experiences of victimization is complex; we do not have research illustrating how these factors intersect to shape the health of nonmetropolitan SGM youth. Similarly, there is a dearth of community-based SGM youth research testing mediating factors of context and health. This study tests tenets of MST to understand how community context shapes experiences of victimization and health among SGM youth.

MST

MST proposes that SGM people face distal or proximal “minority stressors” that account for disparities in health outcomes (Meyer, 2003). Distal stressors are embedded in the social environment and include discrimination and victimization. Proximal stressors are within the individual and include anticipation of rejection, concealment of one’s identity, and internalized homonegativity. Distal and proximal stressors may work independently or together to impact health outcomes. Distal stress has a direct effect on health outcomes, but is also internalized and thus operates indirectly through proximal stressors (Mereish & Poteat, 2015).

The social environment is another critical component of MST (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Meyer, 2003). Minority stressors shape the perception of whether social climates may be affirming of or harmful to people with SGM identities (Meyer, 2003). Affirming environments may disrupt discrimination and victimization, whereas harmful ones can reinforce minority stressors, leading to compromised health. The social environment may be especially critical to the health of SGM youth as they have less autonomy over the settings and contexts they occupy than do adults (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017). Given the increase in social acceptance of SGM people in the United States, SGM youth are coming out earlier than in past years; thus, many may remain dependent on contexts that are oppressive (Russell & Fish, 2019).

SGM Health and Victimization

SGM youth have health disparities when compared with non-SGM youth. Using meta-analysis, Marshall et al. (2011) found that sexual minority youth (SMY) have significantly greater rates of suicidality and depression than heterosexual youth. When compared with non-SGM youth, SGM youth engage in higher rates of substance use, risky sexual behavior, and limited physical activity (Day, Fish, Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, & Russell, 2017; Fish, Schulenberg, & Russell, 2019; Goldbach, Tanner-Smith, Bagwell, & Dunlap, 2014; Kann et al., 2011; Rosario et al., 2014; Zaza, Kann, & Barrios, 2016). These adverse health behaviors are associated with heightened long-term risks of physical health issues, including cancer and heart disease (Rosario et al., 2014). Additional research points to disparately high rates of HIV and STIs (sexually transmitted infections) among SGM youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Finally, some evidence indicates that subsets of SMY, particularly bisexual and female youth, as well as gay males, have higher prevalence of unhealthy weight, obesity, and weight management practices compared with heterosexual peers (Rosario et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2018).

SGM youth are more likely than non-SGM youth to experience victimization in their schools (Poteat, Aragon, Espelage, & Koenig, 2009; Robinson & Espelage, 2011) and homes (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Victimization may take the form of physical acts of violence as well as anti-SGM discrimination or threats. GLSEN found that 98.5% of SGM students indicated they overheard anti-SGM language used in school, 70% reported experiencing verbal harassment based on their sexual orientation, and over half reported harassment based on gender identity or expression (Kosciw et al., 2018). In addition, SGM youth may experience rejection in their own homes due to a lack of acceptance toward SGM identities (Ryan et al., 2009).

A few studies have documented the relationship between SGM identity, victimization, and health outcomes. Nonphysical victimization, such as overhearing anti-SGM comments or being teased, is associated with increased depression, anxiety (Paceley, Goffnett, & Gandy-Guedes, 2017a; Tucker et al., 2016), and stress (Woodford, Paceley, Kulick, & Hong, 2015) among SGM youth. Perceived discrimination mediates the relationship between sexual orientation and symptoms of depression (Almeida et al., 2009), heavy alcohol use (Fish et al., 2019; Pollitt, Mallory, & Fish, 2018), and self-reported physical health (Mereish & Poteat, 2015). In a study of transgender youth, Hatchel, Valido, De Pedro, Huang, and Espelage (2019) found that victimization was associated with greater depression and suicidal ideation. In a population-based study of transgender youth, Day et al. (2017) reported that victimization was mediated by the association between gender identity and substance use.

Community Context

The community context for SGM youth includes two factors: size and climate. Community size has often been conceptualized as nonmetropolitan versus metropolitan, although some SGM research includes small metropolitan communities—which have greater population than rural communities, but are outside a major metropolitan area—to examine community size across a continuum (Oswald et al., 2010; Paceley, Okrey-Anderson, Heumann, 2017b). In addition, community climate is an important component of SGM youths’ contexts. Climate may include the presence or absence of supportive policies, open-and affirming churches, other SGM people, anti-SGM rhetoric, and visibility of SGM identities (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Oswald et al., 2010; Paceley et al., 2018; Woodford et al., 2015).

Community size and climate may intersect. Some research on nonmetropolitan SGM youth indicates that they experience hostile social climates, anti-SGM stigma (Swank et al., 2013), and teachers with hostile attitudes toward sexual minority students (O’Connell et al., 2010). In a study of transgender youth, no nonmetropolitan participants rated their community as supportive (Paceley et al., 2017b). Alternatively, SGM youth have identified supportive aspects of the small towns in which they live (Paceley et al., 2018), suggesting the relationship between community size and climate may be more variable than previous research has considered.

Community context and SGM health.

Although there is limited research on the health experiences of nonmetropolitan SGM youth, a few studies indicate that nonmetropolitan SGM youth have health disparities when compared with metropolitan SGM youth and nonmetropolitan non-SGM youth. SGM youth report greater suicide risk and drug use (Ballard et al., 2017) and greater affective distress (Cohn & Leake, 2012) than nonmetropolitan, heterosexual and cisgender youth. Yet, when compared with metropolitan SGM youth, nonmetropolitan SGM youth report more suicidal thoughts and substance use (Poon & Saewyc, 2009). Community climate is also associated with health outcomes among SGM youth. A supportive climate is associated with fewer symptoms of alcohol abuse and sexual partners (Olson, Cadge, & Harrison, 2006); a hostile climate is associated with the increased risk of suicide attempts (Hatzenbuehler, 2011), anxiety, and stress (Woodford et al., 2015). Importantly, these studies examine the relationship between community context and SGM youth health through either community size or climate, not both together. Such approaches may miss important distinctions in how size and climate operate together to influence SGM youths’ experiences and health.

Community context and victimization.

Research on victimization of nonmetropolitan SGM youth suggests that they experience victimization at rates greater than urban SGM youth (Ballard et al., 2017). In schools, nonmetropolitan SGM youth report overhearing more homophobic language than metropolitan SGM youth (Palmer et al., 2012). In addition, SGM students living in small towns reported greater school-based anti-SGM rhetoric, victimization, and discrimination than urban SGM youth (Kosciw et al., 2018). Research examining the association between victimization and climate among SGM youth has primarily focused on schools. These studies suggest that a more supportive school climate is associated with lower rates of bullying and victimization (De Pedro, Lynch, & Esqueda, 2018; Gower et al., 2018). Studies examining community climate have primarily focused on SGM adults and health. However, some studies have used victimization as an indicator of a hostile climate toward SGM individuals (Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2011) rather than as an outcome of a hostile climate. Thus, we currently do not have an adequate understanding of how community climate and victimization operate for SGM youth.

Community Context, Victimization, and SGM Health Disparities

Few studies have examined community size, climate, and victimization together to understand their individual and collective impacts on SGM youth health. One study examined the association between victimization and SMY health disparities by community size and found that nonmetropolitan SMY experienced greater amounts of victimization than nonmetropolitan heterosexual youth, and that experiences of victimization mediated the relationship between SMY identity and drug use, but not suicide risk (Ballard et al., 2017). This study draws important conclusions about the relationship between victimization and health among nonmetropolitan SMY; however, it did not examine the relationship between community and health. One prior work using data from the current study examined the collective impact of victimization, community size, and climate on mental health outcomes among SGM youth and found that only nonphysical victimization predicted increases in depression, anxiety, and stress, whereas community size predicted increases in stress only (Paceley et al., 2017a). Community climate was not significant in these findings. Although few, these studies suggest that the contexts in which youth are situated are important to their well-being.

Gaps in the Literature

Research demonstrates that nonmetropolitan youth are at elevated risk of victimization and poor health outcomes. However, we lack studies that attempt to untangle the complex relationships between community size, climate, victimization, and health outcomes among SGM youth. Among nonmetropolitan SGM youth, research has yet to identify the independent and shared effects of community size and climate on health outcomes; we know little about whether it is the smaller population of a community or a lack of support toward SGM people contributing to health outcomes. Furthermore, we know that victimization mediates the relationship between SGM identity and health, yet the relationship between victimization and community climate, and how these factors are related to health, remains unclear. Victimization has been measured as a component of climate as well as an outcome, obscuring the relationships among victimization, community context, and health. Therefore, this study tests tenets of MST to understand the relationship between community context, victimization, and health among SGM youth. We contend that victimization should be driven by context rather than studied as a separate predictor and aim to test this hypothesis in the current study. We extend previous work by testing whether youth reports of victimization mediate the relationship between community factors and health. We sought to answer the following research questions:

Research Question 1: Do community size and climate affect the health and mental health of SGM youth?

Research Question 2: Does victimization mediate the relationship among health, mental health, and community size and climate among SGM youth?

Method

Data Source and Sample

We used data from the quantitative survey of a mixed-methods study. The online survey measured perceived physical health, mental health, victimization, community context (size and climate), and demographics. SGM youth (aged 14–18 years) across one Midwestern state were eligible to participate. Participants were recruited via in-person fliers and social media advertisements. Youth completed the survey on their own time after reading an online informed assent/consent. The survey took 20 to 40 minutes to complete, and participants could enter a drawing for a US$20 gift card. All ethical research standards, including a waiver of parental consent, were reviewed and approved by the (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) Institutional Review Board.

The sample for the current study was restricted to youth who were not missing on at least one health-related outcome; however, most youth who completed one health outcome completed all three. This resulted in a final analytic sample of n = 201.

The sample was majority youth assigned female at birth (81.41%), cisgender (72.14%), and non-Latinx, White (76.50%) relative to assigned male, transgender, and all other race/ethnicities, respectively. One quarter (25.63%) of youth reported a gay/lesbian identity, 24.62% bisexual, 18.09% questioning, and 3.66% pansexual or queer. Youth were on average 16.28 years (SD = 1.24). Almost half (47.40%) reported receiving free and reduced lunch at schools. Among youth in the sample, 38.30% lived in a medium or large metropolitan area, 33.83% in a small metropolitan area, and 26.87% in a nonmetropolitan area. Roughly 63% perceived their community climate as tolerant, 22.50% as supportive, and 14.50% as hostile.

Measures

Perceived physical health.

Youth’s self-reported health was measured with a single question derived from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Harris, 2009): “How good is your health?” Response options ranged from “poor” (0) to “excellent” (4). Single-item measures of self-reported health are well-validated strategy to assess correlates of overall health (Ahmad, Jhaji, Stewart, Burghardt, & Bierman, 2014; DeSalvo et al., 2006). Youth in our sample had a mean score of physical health of M = 2.05 (SD = 1.02).

Mental health.

We assessed mental health using the depression and anxiety subscales from the depression, anxiety, and stress scale, short version (DASS-21, Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Participants indicated how often they experienced each symptom on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from “did not apply to me at all” (0) to “all of the time” (3). Each subscale consists seven items and demonstrated good reliability with our sample (depression, α = .88 and anxiety, α = .81) and has shown good validity and reliability in other studies (e.g., Henry & Crawford, 2005: depression, α = .88, 95% confidence interval, CI = [.87, .89] and anxiety, α = .90, 95% CI = [.89, .91]). Mean levels of anxiety and depression for the current sample were M = 1.16 (SD = .73) and M = 1.45 (SD = .80), respectively.

Anti-SGM victimization.

Victimization was measured using a 13-item scale, which asked how frequently youth had experienced various forms of victimization based on their SGM identity in the past year (Oswald & Holman, 2013). Scale items included overheard anti-SGM comments, teased, threatened, pushed, sexually assaulted, asked to leave, kicked out of the house, damaged property, and so on. Response options ranged from “never” (0) to “daily” (7). Items were summed and averaged so that higher scores reflect more anti-SGM victimization. The scale showed adequate reliability with our sample (α = .90). The overall sample mean for victimization was M = 2.37 (SD = .88).

Community context.

Community context included community size and perceived community climate. Participants were asked to include their zip code or town. Community size was calculated at the county level using categories delineated by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS, 2014) Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. NCHS determines a county’s classification based on population size and relationship to metropolitan statistical areas (MSA). Community size was collapsed into nonmetropolitan (< 250,000, outside of an MSA), small metropolitan (< 250,000, within an MSA), and medium/large metropolitan (> 250,000, within an MSA). Perceived community climate was measured by asking “What is the climate toward LGBTQ people where you live?” with the answer options of hostile, tolerant, or supportive (Oswald & Holman, 2013).

Demographics.

Participants were asked to include their age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, sexual identity, and whether they received free/reduced lunch from a list of options, including write-in options. Participants rated their level of outness about their SGM identity to various people, with answer choices ranging from “no one knows” (0) to “everyone knows” (4; Oswald & Holman, 2013). A mean score was derived to indicate their overall level of outness.

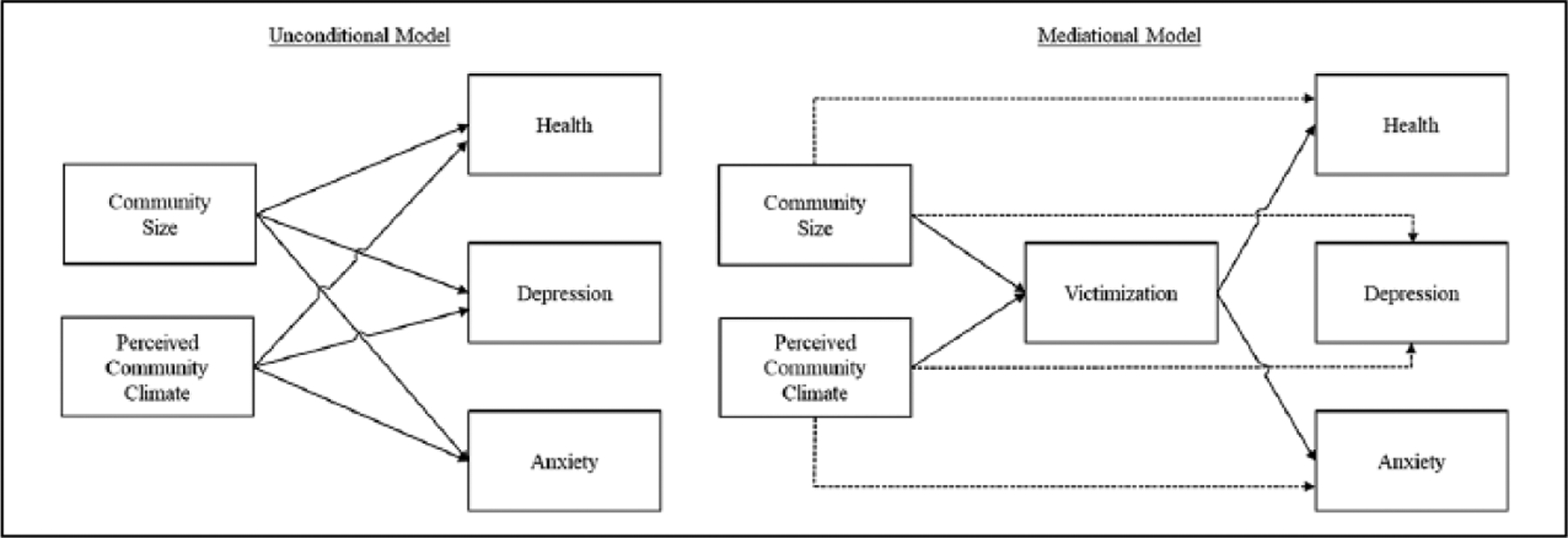

Analytic Approach

First, we conducted bivariate analyses, testing whether health-related outcomes varied across community context using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Next, we estimated the association between community context and health-related outcomes in a multivariable regression using a path-analysis framework. All outcomes were modeled simultaneously to account for shared variance and to estimate independent effects between independent, dependent, and mediating variables. First, we estimated the main effects among community size and climate on self-reported health, anxiety, and depression (see unconditional model, Figure 1), adjusting for race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual identity, age, and receipt of free and reduced lunch. We then tested whether victimization mediated the association between climate and health-related outcomes (see mediational model, Figure 1). Indirect effects were tested using 5,000 bootstrap draws to provide bias-corrected 95% CIs for effects (Hayes, 2009).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model testing the association between metropolitan size and perceived community climate with self-reported health, depression, and anxiety (unconditional model) and the mediating effect of victimization (mediational model).

Although we hypothesized that associations between perceived climate and health are mediated by victimization, we tested a plausible alternative model to this hypothesis. That is, in contrast to our hypothesis, victimization may influence youths’ perceptions of their community climate and subsequently their health. In other words, perceived climate may mediate the association between victimization and health. Given this possibility, and because our data are cross-sectional, we tested this alternative model to see if it fit the data better than our original model.

Data management and bivariate analysis were conducted in Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017). Multivariable path-analysis regression models, mediational models, and the testing of indirect effects were estimated using Mplus 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). We used full-information likelihood estimation methods in Mplus to account for missing values.

Results

Preliminary bivariate analysis, which tests differences in health outcomes by indicators of climate, is shown in Table 1. Community climate indicators were unrelated to self-reported health. However, levels of anxiety, F(2, 194) = 5.59, p = .004, and depression, F(2, 193) = 10.27, p < .001, statistically differed on the basis of community climate: Youth who perceived their community climate as supportive reported statistically less anxiety and depression compared with youth who perceived their communities as hostile or tolerant. Experiences of victimization also differed for youth on the basis of community size, F(2, 198) = 3.50, p = .032, and perceived climate, F(2, 197) = 18.44, p < .001. Specifically, nonmetropolitan youth reported more victimization than youth in small or medium/large metropolitan areas. Youth in supportive climates reported significantly lower levels of victimization than those in hostile or tolerant climates. Furthermore, youth in tolerant communities reported less victimization than youth in hostile communities.

Table 1.

Mean Differences in Self-Reported Health, Anxiety, Depression, and Victimization by Community Size and Community Climate.

| Health | Anxiety | Depression | Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SE) | M | (SE) | M | (SE) | M | (SE) | |

| Community size | ||||||||

| Medium or large metro | 2.08 | (.11) | 1.07 | (.08) | 1.32 | (.09) | 2.19 | (.10)a |

| Small metro | 2.13 | (.12) | 1.24 | (.09) | 1.51 | (.10) | 2.39 | (.10) |

| Nonmetro | 1.96 | (.14) | 1.17 | (.10) | 1.58 | (.11) | 2.59 | (.12)a |

| Perceived community climate | ||||||||

| Supportive | 1.83 | (.19) | 0.85 | (.11)ab | 1.83 | (.14)ab | 1.91 | (.12)bc |

| Hostile | 2.01 | (.09) | 1.32 | (.13)a | 1.51 | (.07)a | 3.07 | (.15)ab |

| Tolerant | 2.40 | (.15) | 1.23 | (.06)b | 1.05 | (.11)b | 2.37 | (.07)ac |

Note. Values with the same subscript denote significant differences at p < .05. Multiple comparisons adjusted for family wise error rate using Bonferonni post hoc adjustments.

Main Effects: Community Climate and Health

Results from unconditional multivariable path models (Table 2) indicated that community climate was associated with anxiety and depression but not physical health—although this association approached significance. Specifically, youth who perceived their community to be tolerant or hostile reported greater anxiety and depression than youth who perceived their community as supportive. Community size was unrelated to health outcomes.

Table 2.

Regression Coefficients From the Unconditional and Mediation Models Testing the Effects of Community Size and Perceived Community Climate on Self-Reported Health, Anxiety, and Depression.

| Health | Anxiety | Depression | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional | Mediation | Unconditional | Mediation | Unconditional | Mediation | |||||||||||||

| β | (SE) | p | β | (SE) | p | β | (SE) | p | β | (SE) | p | β | (SE) | p | β | (SE) | p | |

| Community size | ||||||||||||||||||

| Medium and large metropolitan (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Small metropolitan | −.01 | (.08) | .924 | .00 | (.08) | .999 | .13 | (.08) | .098 | .06 | (.07) | .393 | .14 | (.07) | .058 | .09 | (.07) | .203 |

| Nonmetropolitan | −.02 | (.08) | .800 | −.02 | (.08) | .851 | −.02 | (.08) | .819 | −.07 | (.07) | .348 | .04 | (.08) | .570 | .01 | (.07) | .947 |

| Subjective community climate | ||||||||||||||||||

| Supportive (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hostile | −.17 | (.09) | .053 | −.15 | (.10) | .115 | .21 | (.08) | .015 | .03 | (.08) | .739 | .29 | (.08) | .001 | .15 | (.09) | .078 |

| Tolerant | −.16 | (.09) | .066 | −.15 | (.09) | .095 | .25 | (.08) | .003 | .15 | (.08) | .049 | .26 | (.08) | .001 | .18 | (.08) | .019 |

| Victimization | −.05 | (.08) | .561 | .41 | (.07) | .000 | .31 | (.07) | .000 | |||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Non-Latinx, White (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Racial/ethnic minority | −.03 | (.07) | .654 | −.04 | (.07) | .619 | −.10 | (.07) | .144 | −.07 | (.07) | .280 | −.10 | (.07) | .126 | −.08 | (.07) | .223 |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Female | .03 | (.08) | .745 | .02 | (.08) | .785 | .06 | (.08) | .433 | .10 | (.07) | .161 | .16 | (.07) | .027 | .19 | (.07) | .006 |

| Gender identity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cisgender (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Transgender | −.03 | (.07) | .668 | −.03 | (.07) | .729 | −.05 | (.07) | .461 | −.11 | (.07) | .104 | −.03 | (.07) | .718 | −.07 | (.07) | .317 |

| Sexual identity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lesbian/gay (reference) Bisexual | −.02 | (.09) | .835 | −.03 | (.09) | .780 | .03 | (.09) | .699 | .09 | (.08) | .273 | .00 | (.08) | .999 | .04 | (.08) | .604 |

| Pansexual or queer | −.05 | (.10) | .634 | −.05 | (.10) | .612 | .12 | (.09) | .196 | .15 | (.08) | .083 | .11 | (.09) | .232 | .13 | (.09) | .133 |

| Questioning | −.05 | (.09) | .581 | −.05 | (.09) | .562 | .08 | (.09) | .343 | .10 | (.08) | .193 | .09 | (.08) | .267 | .11 | (.08) | .172 |

| Age | −.06 | (.07) | .394 | −.07 | (.07) | .354 | −.15 | (.07) | .034 | −.09 | (.06) | .157 | −.07 | (.07) | .275 | −.03 | (.06) | .629 |

| Free and reduced lunch | ||||||||||||||||||

| No (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | −.09 | (.07) | .214 | −.09 | (.07) | .243 | .09 | (.07) | .204 | .04 | (.07) | .525 | .10 | (.07) | .140 | .07 | (.07) | .324 |

| R2 for outcome | .050 | .050 | .127 | .261 | .176 | .255 | ||||||||||||

Note. Dependence variables were simultaneously modeled in a path analysis framework to account for shared variance. Missing data are accounted for using full-information maximum likelihood estimation. R2 for victimization was .180. Unconditional model is just identified. Model fit for mediational model: AIC = 4,831.51; BIC = 5,307.82; χ2 = 15.72; df = 8; p = .047; RMSEA = .070; CFI = .970; SRMS = .021. Model fit for alternative model: AIC = 4,899.33; BIC = 5,345.28; χ2 = 101.54; df = 17; p < .001; RMSEA = .157; CFI = .743; SRMR = .049. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; RMSEA = root mean square error approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; CFI = comparative fit index.

Mediating Effects of Victimization

Direct, indirect, and total effects of victimization as a mediator between community climate and health outcomes are presented in Table 3. As hypothesized, victimization statistically mediated the association between perceived climate and anxiety and depression. Experiences of victimization partially explained the difference in anxiety and depression for youth who perceived their community to be hostile or tolerant, in comparison with youth who perceived their community to be supportive. No other significant mediating effects were noted. Interestingly, when victimization was added to the model, the direct effects between community climate and anxiety and depression were no longer significant for youth who perceived their community to be hostile or tolerant relative to youth who perceived their community as supportive.

Table 3.

Total, Indirect, and Direct Effects of Victimization as a Mediator Between Community Size, Community Climate, and Health-Related Outcomes.

| Health | Anxiety | Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | (95% CI) | p | β | (95% CI) | p | β | (95% CI) | p | |

| Subjective community climate | |||||||||

| Supportive (reference) | |||||||||

| Hostile | |||||||||

| Total | −.17 | [−.35, .01] | .061 | .22 | [.06, .38] | .007 | .30 | [.14, .46] | .000 |

| Indirect | −.02 | [−.11, .06] | .618 | .20 | [.10, .29] | .000 | .15 | [.06, .24] | .001 |

| Direct | −.15 | [−.33, .03] | .100 | .03 | [−.14, .20] | .749 | .15 | [−.04, .34] | .114 |

| Tolerant | |||||||||

| Total | −.16 | [−.33, .01] | .066 | .26 | [.11, .42] | .001 | .27 | [.11, .42] | .001 |

| Indirect | −.01 | [−.06, .04] | .616 | .11 | [.04, .18] | .002 | .08 | [.03, .14] | .005 |

| Direct | −.15 | [−.31, .02] | .085 | .15 | [.00, .31] | .057 | .18 | [.03, .34] | .024 |

Note. Indirect effects were estimated using 5,000 bootstrap draws to provide bias-correct 95% confidence intervals. CI = confidence interval.

Finally, we assessed whether an alternative model fit our data better than our hypothesized model. Specifically, we tested whether perceived community climate mediated the association between community size, victimization, and our health outcomes. Results of chi-square and log-likelihood difference tests indicated that this alternative model was a statistically worse fit to the data (Δχ2 = 85.82, Δdf = 9, p < .0001; ΔLL = 42.91, df = 2, p < .0001), suggesting that our hypothesized model fit the data better.

Discussion

This study tested tenets of MST to understand how SGM youth’s community context is associated with health. In addition, we examined victimization as a mediator between community climate and health. Results indicated that climate was a more robust indicator than size in the relationship between community context and health among SGM youth. SGM youth in hostile or tolerant communities reported more anxiety and depression than SGM youth who lived in supportive communities. As hypothesized, victimization mediated this relationship, such that for youth in tolerant or hostile communities, experiences of victimization partially explained their elevated rates of anxiety and depression, relative to youth in supportive communities. Our hypothesis is strengthened by our testing of an alternative model that victimization mediates the relationship between community climate and health, rather than a driving force behind youths’ perceptions of their community. Neither community size nor climate predicted physical health; however, youth in nonmetropolitan and in hostile or tolerant communities reported more incidence of victimization than youth in metropolitan and supportive communities, respectively.

These findings provide important contributions to our understanding of how minority stress and its association with health outcomes varies by community context for SGM youth. Previous research has identified that living in a nonmetropolitan (Ballard et al., 2017; Cohn & Leake, 2012; Palmer et al., 2012; Poon & Saewyc, 2009) or hostile climate (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Woodford et al., 2015) increases SGM young people’s risks of poor mental health. Few studies have examined climate in tandem with size to determine their individual or collective impacts on mental health. The findings from this study suggest that, after accounting for community size, climate is both directly and indirectly related to depression and anxiety among SGM youth. These findings do not diminish the relevance of community size. Multiple studies have illustrated a connection between size and climate; nonmetropolitan SGM youth generally report more hostile climates than youth in larger communities (O’Connell et al., 2010; Paceley et al., 2018; Swank et al., 2013). In addition, the bivariate results from this study found SGM youth reported greater victimization in nonmetropolitan communities. Given the connection between victimization and mental health in this and other studies (Almeida et al., 2009; Hatchel et al., 2019; Tucker et al., 2016), results emphasizes the confluence of community size, climate, and mental health. The results of this study underscore the value of examining community context in a more complex manner including checking assumptions about associations between community size and climate and the importance of broader community climate as a factor for SGM youths’ well-being.

These findings enhance our understanding of the complex interaction between community climate and victimization and how they affect SGM youth’s mental health. Previous research examined victimization as a component of community climate, rather than as a separate predictor (Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, 2014; D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 1998; Russell et al., 2011). Our findings indicate that victimization helps explain why SGM youth in hostile climates report worse mental health than SGM youth in supportive contexts. Importantly, adjusting for youths’ experiences of victimization attenuated differences in depression and anxiety between SGM youth in supportive and hostile climates. Mental health differences between youth in tolerant and hostile climates remained, which suggests that there may be additional factors for youth in tolerant climates that place them at increased risk of poor mental health.

It is important to note that we found no statistical relationship between perception of physical health and community context. This may be related to our single measure of self-perception of physical health rather than a measure of symptoms. It could also be that stress-related indicators of health are more likely to manifest over time or at later stages of the life course.

Limitations

This study contributes meaningfully to our knowledge about SGM youth health; however, it is not without limitation. The study sample is drawn from a nonprobability sample and is not generalizable to SGM youth more broadly. The study relies on a single, self-reported measure of physical health, which may have response bias and does not provide the more detailed, symptom-based information available in measures of mental health. Data are cross-sectional and cannot be used to make claims of temporality or causality. Our alternative modeling testing strengthens our inferences, but longitudinal data would be a more robust test of the time-ordered relationship between these variables.

Implications for Research and Practice

Our findings have notable implications for research and practice with SGM youth. Results provide evidence highlighting the necessity of considering community climate in addition to community size when assessing the relationship between community and health. Findings support a conceptual distinction between community climate and size, emphasizing the importance of qualitative features of communities in supporting the health of SGM youth. We need more qualitative understandings of what influences SGM youths’ perceptions of their community climate within various community sizes. Future studies could identify factors that may shift a community climate from hostile to supportive and then test interventions to reduce victimization and promote acceptance. Theoretical work is necessary to define and operationalize the complex relationship between community climate and victimization. Researchers attending to community climate among SGM youth may want to consider a multidomain indicator of climate that includes victimization as a component (e.g., latent construct) of climate.

Future research should also attend to the role of community size and geographic region in studies with SGM youth by examining climate and size together, alongside other relevant factors such as the presence and/or utilization of SGM resources. It will be important for research to consider community size on a continuum rather than solely as a dichotomy, which may leave out smaller communities that are not rural, but lack SGM resources (Paceley et al., 2018).

Finally, there are established physical health disparities between SGM and non-SGM adults, but little is known about the physical health of SGM youth. Our findings join a small set of studies to examine SGM youth physical health outcomes, and much more research is needed in this area. It may be useful for researchers to employ more complex measures of physical health including youth-specific measures for health indicators of stress (e.g., psychosomatic symptomology).

Coupled with a robust and growing body of research examining SGM youth outcomes, our findings suggest the urgency of researcher and practitioner action toward intervention and change. The results of this study emphasize the importance of developing, testing, and implementing interventions to support the health of SGM youth, with particular emphasis on the role of community as an important point of intervention. Results suggest there may be distinct needs of SGM youth on the basis of community characteristics, and this might inform context-specific intervention efforts. Prior research suggests that supportive community climates for nonmetropolitan SGM youth may include supportive people, SGM visibility, SGM resources and education, and SGM-inclusive policies (Paceley et al., 2018). Although additional research is needed in this area, these represent concrete interventions social workers, activists, and other practitioners can implement to shift a community’s climate from hostile or tolerant to supportive.

Given our finding that victimization mediates the relationship between climate and mental health, it is important to implement interventions to reduce victimization toward SGM people. This may mean enacting and enforcing nondiscrimination and antibullying/victimization policies that are inclusive of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities. Trainings or community awareness campaigns may provide opportunities to educate other professionals or the general public on issues affecting SGM youth. Our findings make a clear case for supportive community climates as a viable vehicle for the promotion of SGM youth health. By better understanding the role of communities in diminishing or enabling health, we can identify and test community-level interventions to reduce stigma and victimization and promote well-being among SGM youth. Doing so places the onus of change on social systems enacting stigma, rather than on the youth being affected by their social environments.

Acknowledgments

The first author wishes to thank her dissertation committee for their assistance with this study: Janet Liechty, Ramona F. Oswald, Benjamin Lough, Jennifer Greene, and Shelley Craig.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by a Small Research Grant from The Williams Institute and the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Graduate College.

Author Biographies

Megan S. Paceley is an assistant professor at the University of Kansas School of Social Welfare. She studies the role of the social context in the health and well-being of sexual and gender minority young people.

Jessica N. Fish is an assistant professor in the Department of Family Science at the University of Maryland School of Public Health. Her research aims to identify modifiable factors that contribute to sexual orientation and gender identity-related health disparities in order to inform developmentally-sensitive policies, programs, and prevention strategies that promote the health of sexual and gender minority people across the life course.

Margaret M. C. Thomas is a PhD Candidate at Boston University School of Social Work. Her research centers on public policy with a focus on deprivation, poverty, and wellbeing among children and families.

Jacob Goffnett is a doctoral candidate in Social Work at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research looks at the social determinants of behavioral health outcomes for sexual and gender minority populations.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Findings are discussed in light of current literature and implications for research and practice are shared.

References

- Ahmad F, Jhaji AK, Stewart DE, Burghardt M, & Bierman AS (2014). Single item measures of self-rated mental health: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 398–409. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, & Azrael D (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard ME, Jameson JP, & Martz DM (2017). Sexual identity and risk behaviors among adolescents in rural Appalachia. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 41, 17–29. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton CM, Marshal MP, Chisolm DJ, Sucato GS, & Friedman MS (2013). Sexual minority-related victimization as a mediator of mental health disparities in sexual minority youth: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 394–402. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9901-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). HIV by group. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/index.html

- Cohn TJ, & Leake VS (2012). Affective distress among adolescents who endorse same-sex sexual attraction: Urban versus rural differences and the role of protective factors. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 16, 291–305. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2012.690931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ, Johnson CC, & Joseph CLM (2016). The mental health of transgender youth: Advances in understanding. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59, 489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, & Pilkington N (1998). LEsbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families; Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Russell ST (2017). Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. Journal of Adoelscent Health, 61, 729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jado-health.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pedro KT, Lynch RJ, & Esqueda MC (2018). Understanding safety, victimization and school climate among rural lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 15, 265–279. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2018.142050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP, Tran K, Bloser N, Merrill W, & Peabody J (2006). Assessing measurement properties of two single-item general health measures. Quality of Life Research, 15, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DT, & Hatzenbuehler ML (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 272–278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Schulenberg JE, & Russell ST (2019). Sexual minority youth report high-intensity binge drinking: The critical role of school victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64, 186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, & Gibbs JJ (2017). A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, & Dunlap S (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15, 350–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower AL, Forster MF, Gloppen K, Johnson AZ, Eisenberg ME, Connett JE, & Borowsky IW (2018). School practices to foster LGBT-supportive climate: Associations with adolescent bullying involvement. Prevention Science, 19, 813–821. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0847-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM (2009). The national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health (add health), waves I & II, 1994–1996; wave III, 2001–2002; wave IV, 2007–2009 (Machine-readable data file and documentation). Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel T, Valido A, De Pedro KT, Huang Y, & Espelage D (2019). Minority stress among transgender adolescents: The role of peer victimization, school belonging, and ethnicity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2467–2476. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1168-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2011). The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics, 127, 896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, & Crawford JR (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, O’Malley, Olsen E, Mcmanus T, Kinchen S, Chyen D, Harris WA, & Wechsler H (2011). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12: Youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 60, 1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Giga NM, & Danischewski DJ (2016). The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, Clark CM, & Truong NL (2018). The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Lick DJ, Durso LE, & Johnson KL (2013). Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, & Lovibond PF (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Psychology Foundation of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith H, McGinley J, … Brent DA (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adoelscent Health, 49, 115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH, & Poteat VP (2015). A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 425–437. doi: 10.1037/cou0000088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2014). 2013 NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell LM, Atlas JG, Saunders AL, & Philbrick R (2010). Perceptions of rural school staff regarding sexual minority students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 7, 293–309. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2010.518534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L, Cadge W, & Harrison J (2006). Religion and public opinion about same-sex marriage. Social Science Quarterly, 87, 340–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00384.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald RF, Cuthbertson C, Lazarevic V, & Goldberg AE (2010). New developments in the field: Measuring community climate. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6, 214–228. doi: 10.1080/15504281003709230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald RF, & Holman EG (2013). Rainbow Illinois: How downstate LGBT communities have changed (2000–2011). Urbana: Department of Human and Community Development, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. [Google Scholar]

- Paceley MS, Goffnett J, & Gandy-Guedes M (2017a). Impact of victimization, community climate, and community size on the mental health of sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 658–671. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pacelely MS, Okrey-Anderson S, & Heumann M (2017b). Transgender youth in small towns: Perceptions of community size, climate, and support. Journal of Youth Studies, 7, 822–840. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1273514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paceley MS, Thomas MMC, Toole J., & Pavicic E (2018). “If rainbows were everywhere”: Nonmetropolitan SGM youth identify factors that make communities supportive. Journal of Community Practice, 26, 429–445. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2018.1520773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer NA, Kosciw JG, & Bartkiewicz MJ (2012). Strengths and silences: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students in rural and small town schools. New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt AM, Mallory AB, & Fish JN (2018). Homophobic bullying and sexual minority youth alcohol use: Do sex and race/ethnicity matter? LGBT Health, 5, 412–420. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS, & Saewyc EM (2009). Out yonder: Sexual-minority adolescents in rural communities in British Columbia. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 118–124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Aragon SR, Espelage DL, & Koenig BW (2009). Psychosocial concerns of sexual minority youth: Complexity and caution in group differences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 196–201. doi: 10.1037/a0014158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JP, & Espelage DL (2011). Inequities in educational and psychological outcomes between LGBTQ and straight students in middle and high school. Educational Researcher, 40, 315–330. doi: 10.3102/0013189X11422112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Corliss HL, Everett BG, Reisner SL, Austin SB, Buchting FO, & Birkett M (2014). Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and physical activity: Pooled youth risk behavior surveys. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 245–254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST & Fish JN (2019). Sexual minority youth, social change, and health: A developmental collision. Research in Human Development, 16, 5–20. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2018.1537772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S, Ryan C, Toomey R, Diaz R, & Sanchez J (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: Implications for young adult health and adjustment. Journal of School Health, 81, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, & Sanchez J (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123, 346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Swank E, Fahs B, & Frost DM (2013). Region, social identities, and disclosure practices as predictors of heterosexist discrimination against sexual minorities in the United States. Sociological Inquiry, 83, 238–258. doi: 10.1111/soin.12004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ewing BA, Espelage DL, Green HD Jr., de la Haye K, & Pollard MS (2016). Longitudinal associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with psychological distress and alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59, 110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, VanKim NA, Rose HA, Porta CM, Gahagan J, & Eisenberg ME (2018). Unhealthy weight control behaviors among youth: Sex of sexual partner is linked to important differences. Eating Disorders, 26, 448–463. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2018.1453633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienke C, & Hill GJ (2013). Does place of residence matter? Rural-urban differences and the wellbeing of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 1256–1279. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.806166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford MR, Paceley MS, Kulick A, & Hong JS (2015). The LGBQ social climate matters: Policies, protests, and placards and psychological well-being among LGBQ emerging adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 27, 116–141. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2015.990334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough DG (2003). Gay adolescents in rural areas: Experiences and coping strategies. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 8, 129–144. doi: 10.1300/J137v08n02_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaza S, Kann L, & Barrios LC (2016). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: Population estimate and prevalence of health behaviors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 316, 2355–2356. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]