Abstract

Objective

To assess the temporal trend and identify risk factors associated with the absence of previous HIV testing prior to their diagnosis among HIV-positive persons in Singapore.

Study design

Cross-sectional.

Setting and participants

We analysed data of HIV-positive persons infected via sexual transmission, who were notified to the National HIV Registry in 2012–2017.

Outcomes

Epidemiological factors associated with the absence of HIV testing prior to diagnosis were determined separately for two groups of HIV-positive persons: early and late stages of HIV infection at diagnosis.

Results

2188 HIV-positive persons with information on HIV testing history and CD4 cell count were included in the study. The median age at HIV diagnosis was 40 years (IQR 30–51). Nearly half (45.1%) had never been tested for HIV prior to their diagnosis. The most common reason cited for no previous HIV testing was ‘not necessary to test’ (73.7%). The proportion diagnosed at late-stage HIV infection was significantly higher among HIV-positive persons who had never been tested for HIV (63.9%) compared with those who had undergone previous HIV tests (29.0%). Common risk factors associated with no previous HIV testing in multivariable logistic regression analysis stratified by stage of HIV infection were: older age at HIV diagnosis, lower educational level, detection via medical care and HIV infection via heterosexual transmission. In the stratified analysis for persons diagnosed at early-stage of HIV infection, in addition to the four risk factors, women and those of Malay ethnicity were also less likely to have previous HIV testing prior to their diagnosis.

Conclusion

Targeted prevention efforts and strategies are needed to raise the level of awareness of HIV/AIDS and to encourage early and regular screening among the at-risk groups by making HIV testing more accessible.

Keywords: epidemiology, HIV & AIDS, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We were able to use the epidemiological data collected in the National HIV Registry in Singapore, which improves the generalisability of the findings.

Not all potential confounding factors associated with the absence of HIV testing prior to HIV diagnosis could be included in our study, and information on drivers and barriers of HIV testing was unavailable.

As testing-related information was ascertained based on self-reporting by HIV-positive persons, some extent of misclassification due to recall bias could not be avoided.

Introduction

Regular HIV testing among at-risk individuals is paramount as a preventive strategy in the programmatic response to HIV/AIDS epidemic. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and partners launched the 90–90–90 targets in 2014, which called for 90% of all people living with HIV (PLHIV) to be aware of their status, 90% of those diagnosed to receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90% of those on ART to achieve viral suppression by 2020.1 The corresponding estimates for PLHIV in Singapore were 80%, 91% and 91% in 2018.2 Regular and frequent HIV testing provides an essential gateway to serostatus awareness and early diagnosis, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of all subsequent steps in the cascade of HIV care including provision of ART and counselling on behaviour. The risk of onward transmission by persons who are unaware of their HIV infection and premature deaths is also reduced with diagnosis of HIV infection at an early stage.

As of end-2019, there were 8618 Singapore residents diagnosed with HIV infection, of whom 2097 had died.3 Despite the widespread availability and accessibility of HIV testing in Singapore, late diagnosis in the course of HIV infection continues to be a barrier in tackling HIV.4 A local study revealed that over half (54%) of HIV-positive persons infected via sexual transmission in 1996–2009 had late-stage disease at diagnosis.5 The higher short-term mortality of persons diagnosed with late-stage HIV infection underscores the importance of testing and detection at the earliest opportunity.6 Another local study found that the median survival of HIV-positive persons diagnosed late was 5 years, whereas the cumulative proportion of those diagnosed early surviving until the fifth year since diagnosis was 80%.7

This study seeks to elucidate epidemiological factors associated with the absence of previous HIV testing prior to their diagnosis separately for HIV-positive persons diagnosed at early and late stages of HIV infection. The findings provide insights into reviewing and tailoring public health preventive and interventional strategies to increase the uptake of HIV testing in at-risk groups, so as to facilitate early diagnosis and timely initiation of ART for HIV-infected persons.

Materials and methods

Study population

Notification of HIV/AIDS diagnosis is mandatory under the Infectious Diseases Act in Singapore.8 Information collected in the National HIV Registry is protected under the law, and includes sociodemographic characteristics, CD4 cell count, mode of detection and exposure factors such as the mode of transmission and the type of sexual partners.

Information on risk factors and current and previous HIV testing behaviour is obtained from review of medical case notes and interviews with persons who are diagnosed with HIV. The mode of HIV transmission consists of sexual contact (heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual), intravenous drug use, blood transfusion, renal transplant overseas, perinatal (mother to child) and uncertain/others. The mode of detection consists of voluntary screening (own request), medical care for HIV-related symptoms and non-HIV care, routine programmatic HIV screening (includes screening programmes for those with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), hospital inpatients and those identified through contact tracing) and other reasons for current HIV testing such as health screening for life insurance application. We classified the type of sexual partners into mutually exclusive categories (regular only; regular and casual only; sex workers and social escorts) based on the following groups: casual; regular; spouse/girlfriend/boyfriend; sex worker (brothel-based), sex worker (non-brothel)/social escort; ex-spouse/ex-girlfriend/ex-boyfriend.

Data on self-reported history of HIV testing has been collected since 2010, and the proportion of missing data dropped from 39% in 2010 to below 20% since 2012. The majority (95.1%) of HIV-positive persons reported in 1985–2017 were infected via sexual transmission, hence, we restricted the analyses to those infected via sexual transmission to allow for a more homogenous group. The study population was sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons diagnosed and notified to the National HIV Registry in 2012–2017. Approval for this study was provided by the Ministry of Health, Singapore. As the data were collected under the Infectious Diseases Act and analyses were performed on an anonymised dataset, informed consent was not required for this study.

The analyses were stratified by stage of HIV infection at diagnosis (early or late), hence, HIV-positive persons with either unknown HIV testing history or missing CD4 count at diagnosis were excluded. Factors associated with no previous HIV testing were deemed to differ depending on the stage of infection at diagnosis, hence, separate analysis was conducted for HIV-positive persons diagnosed at early and late stages of infection. Late-stage HIV infection was defined as having either a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 at the time of diagnosis, or an AIDS-defining illness at diagnosis or within 1 year of HIV diagnosis.5 To ensure accuracy in classifying late-stage HIV infection based on CD4 count <200 cells/mm3, efforts were taken to exclude acute infection through the process of contact tracing interviews, which include questions about previous HIV tests. Recency assays to document or confirm acute infections were not done routinely or universally for all persons newly diagnosed with HIV. We excluded HIV-positive persons whose first available date of CD4 count was more than 90 days after their HIV diagnosis date as they would most likely to have started treatment on their first date of CD4 count, hence, whether these individuals had late-stage infection or not was unknown.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of the study results.

Statistical analysis

Changes in proportions over time were analysed using the χ2 test for trend. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate, was used for comparison of categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess differences between any two groups for continuous variables. For variables with missing data proportion less than 10%, we used missForest (V.1.4), an iterative non-parametric method, to impute the missing values.9

The main outcome was whether the HIV-positive person had previous HIV tests prior to diagnosis. Crude ORs and adjusted OR (aOR) along with 95% CI were calculated based on logistic regression models. Multivariable analysis was conducted to determine factors independently associated with no previous HIV testing. Variables with p<0.10 in the univariable regression analyses were considered for inclusion in a backward selection process and retained in the final multivariable model only when p<0.05. We performed separate logistic regression analyses for two groups: early and late stages of HIV infection at diagnosis.

All p values reported were two-sided and statistical significance was taken as p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.24 (IBM) and R V.3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

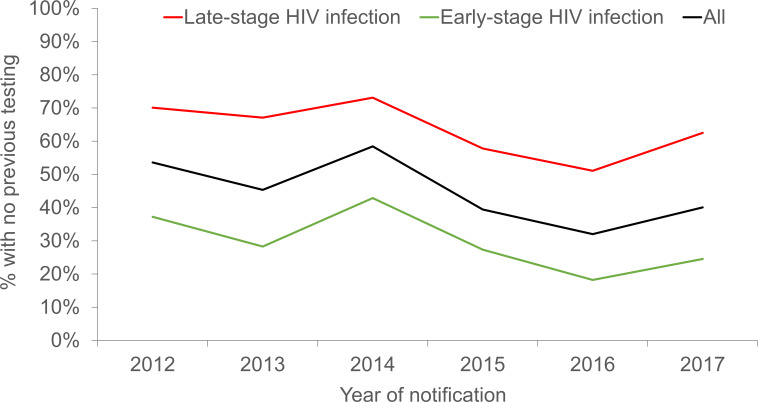

A total of 2579 newly diagnosed HIV-positive persons infected via sexual transmission were notified to the National HIV Registry in 2012–2017. We excluded 391 cases from this study; 282 had unknown HIV testing history and another 109 did not have CD4 cell counts measured at diagnosis. Among the 2188 HIV-positive persons included in the study, 45.1% had no previous HIV testing prior to diagnosis. There was a significant decline in the annual proportion of HIV-positive persons with no previous HIV testing; from 53.6% in 2012 to 40.1% in 2017 (p for trend <0.0005) (figure 1). The annual proportion without previous HIV testing was consistently higher in persons diagnosed at late-stage than early-stage of HIV infection.

Figure 1.

Percentage of sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons who did not have HIV tests prior to diagnosis by stage of HIV infection at diagnosis in Singapore, 2012–2017.

The median age of the 2188 HIV-positive persons was 40 years (IQR 30–51). About 93.5% were men, 71.8% were Chinese, 68.8% had never been married, 67.0% had attained post-secondary education or diploma levels and 62.5% worked in professional/managerial positions or administrative/service sectors (table 1). About 45.7% of the HIV-positive persons were detected during the course of medical care wherein HIV testing was performed as part of the diagnostic evaluation for their presenting symptoms, while 28.1% were detected via routine programmatic HIV screening. Over half of the HIV-positive persons were infected via homosexual/bisexual route of transmission (58.8%), had regular and casual sexual partners only (62.0%), were diagnosed at early-stage of HIV infection (55.3%) and did not have any self-reported history of STIs (76.2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics (%) of sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons by the history of HIV testing prior to diagnosis in Singapore, 2012–2017

| Characteristic | Total (N=2188) | No previous HIV tests (N=986) | Had previous HIV tests (N=1202) | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age group (years) | <0.0005 | |||

| 15–24 | 231 (10.6) | 59 (6.0) | 172 (14.3) | |

| 25–34 | 548 (25.0) | 138 (14.0) | 410 (34.1) | |

| 35–44 | 567 (25.9) | 200 (20.3) | 367 (30.5) | |

| 45–54 | 487 (22.3) | 303 (30.7) | 184 (15.3) | |

| 55–64 | 274 (12.5) | 211 (21.4) | 63 (5.2) | |

| >65 | 81 (3.7) | 75 (7.6) | 6 (0.5) | |

| Gender | <0.0005 | |||

| Male | 2045 (93.5) | 881 (89.4) | 1164 (96.8) | |

| Female | 143 (6.5) | 105 (10.6) | 38 (3.2) | |

| Ethnic group | 0.092 | |||

| Chinese | 1571 (71.8) | 700 (71.0) | 871 (72.5) | |

| Malay | 413 (18.9) | 193 (19.6) | 220 (18.3) | |

| Indian | 122 (5.6) | 64 (6.5) | 58 (4.8) | |

| Others | 82 (3.7) | 29 (2.9) | 53 (4.4) | |

| Marital status | <0.0005 | |||

| Never married | 1506 (68.8) | 504 (51.1) | 1002 (83.4) | |

| Married | 469 (21.4) | 326 (33.1) | 143 (11.9) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 213 (9.7) | 156 (15.8) | 57 (4.7) | |

| Educational level | <0.0005 | |||

| No formal/primary | 161 (7.4) | 129 (13.1) | 32 (2.7) | |

| Secondary | 263 (12.0) | 160 (16.2) | 103 (8.6) | |

| Post-secondary/diploma | 1466 (67.0) | 630 (63.9) | 836 (69.6) | |

| University degree or higher | 290 (13.3) | 63 (6.4) | 227 (18.9) | |

| Unknown | 8 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) | |

| Occupational type | <0.0005 | |||

| Professional/executive | 463 (21.2) | 155 (15.7) | 308 (25.6) | |

| Administrative/service | 904 (41.3) | 380 (38.5) | 524 (43.6) | |

| Blue-collar worker | 285 (13.0) | 227 (23.0) | 58 (4.8) | |

| Unemployed | 69 (3.2) | 43 (4.4) | 26 (2.2) | |

| Others | 302 (13.8) | 112 (11.4) | 190 (15.8) | |

| Unknown | 165 (7.5) | 69 (7.0) | 96 (8.0) | |

| Mode of detection | <0.0005 | |||

| Voluntary screening | 452 (20.7) | 69 (7.0) | 383 (31.9) | |

| Medical care | 1001 (45.7) | 646 (65.5) | 355 (29.5) | |

| Routine programmatic HIV screening* | 615 (28.1) | 241 (24.4) | 374 (31.1) | |

| Others | 120 (5.5) | 30 (3.0) | 90 (7.5) | |

| Mode of HIV transmission | <0.0005 | |||

| Homosexual/bisexual | 1287 (58.8) | 354 (35.9) | 933 (77.6) | |

| Heterosexual | 901 (41.2) | 632 (64.1) | 269 (22.4) | |

| Type of sexual partners | <0.0005 | |||

| Regular only | 246 (11.2) | 126 (12.8) | 120 (10.0) | |

| Regular and casual only | 1357 (62.0) | 471 (47.8) | 886 (73.7) | |

| Sex workers and social escorts | 576 (26.3) | 385 (39.0) | 191 (15.9) | |

| Unknown | 9 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | |

| Self-reported history of STIs | <0.0005 | |||

| No | 1668 (76.2) | 799 (81.0) | 869 (72.3) | |

| Yes | 520 (23.8) | 187 (19.0) | 333 (27.7) | |

| Stage of HIV infection | <0.0005 | |||

| Early | 1210 (55.3) | 356 (36.1) | 854 (71.0) | |

| Late | 978 (44.7) | 630 (63.9) | 348 (29.0) |

*Routine programmatic HIV screening includes screening programmes for those with STIs, hospital inpatients and those identified through contact tracing.

STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Characteristics of HIV-positive persons with and without previous HIV testing

Compared with HIV-positive persons who had previous HIV testing, a significantly higher proportion of those without previous testing were aged 45 years or older at HIV diagnosis (59.7% vs 21.0%), women (10.6% vs 3.2%), had ever been married (48.9% vs 16.6%), had a secondary education or below (29.3% vs 11.2%), and were blue-collar workers (23.0% vs 4.8%) or unemployed (4.4% vs 2.2%) (table 1). A significantly higher proportion of HIV-positive persons without previous HIV tests were diagnosed in the course of medical care (65.5% vs 29.5%), infected via heterosexual transmission (64.1% vs 22.4%) and had sex workers and social escorts as sexual partners (39.0% vs 15.9%). The proportion without any self-reported history of STIs was significantly higher among HIV-positive persons without previous tests than in those who had ever been tested for HIV prior to diagnosis (81.0% vs 72.3%). The proportion of late-stage HIV infection among HIV-positive persons without previous tests was about two times that of those with previous HIV tests (63.9% vs 29.0%).

There was a significant decreasing trend in the age-specific proportion having prior test(s) before HIV diagnosis; this proportion declined from 74.5% in the age group of 15–24 years to 23.0% in those aged 55–64 years and 7.4% in elderly persons aged 65 years or older (p for trend <0.0005).

Comparison of HIV-positive persons included and excluded from the study

Compared with the 391 sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons excluded from the analyses, a significantly higher proportion of those included in this study were aged between 15 and 34 years at HIV diagnosis (35.6% vs 26.1%), never married (68.8% vs 61.6%), had university degree or higher (13.3% vs 7.2%), were detected via voluntary screening (20.7% vs 11.8%) and infected via homosexual/bisexual transmission (58.8% vs 48.8%) (all p<0.01) (online supplemental table). The proportion with unknown occupational type and type of sexual partners was significantly different between these two groups.

bmjopen-2021-050133supp001.pdf (41.5KB, pdf)

Duration from the last test to HIV diagnosis, type of test sites and reasons cited by HIV-positive persons without previous HIV test before diagnosis

Among the 1202 HIV-positive persons who had previous HIV tests, 1122 (93.3%) reported a negative result for the last test prior to diagnosis and their median duration from the last negative test to HIV diagnosis was 2.1 years (IQR 1.0–4.4). This interval was significantly longer at 3.8 years (IQR 2.0–7.3) among the 320 HIV-positive persons diagnosed at late-stage HIV infection compared with 1.7 years (IQR 0.8–3.2) among the 802 HIV-positive persons diagnosed early (p<0.0005).

Of the remaining 80 HIV-positive persons who had previous HIV tests but their last test prior to diagnosis was not negative, 59 reported positive results (24 tested overseas, 23 tested at anonymous test sites, 4 at other places and 8 were unknown) and 21 reported indeterminate results (no information on the test site). Of the 59 HIV-positive persons with previous positive test results for HIV, 30 (50.8%) were detected via voluntary screening, 17 (28.8%) via medical care, 8 (13.6%) via routine programmatic HIV screening and 4 (6.8%) via other modes. The median duration from the first positive test to HIV diagnosis was 1.1 years (IQR 0.2–5.9).

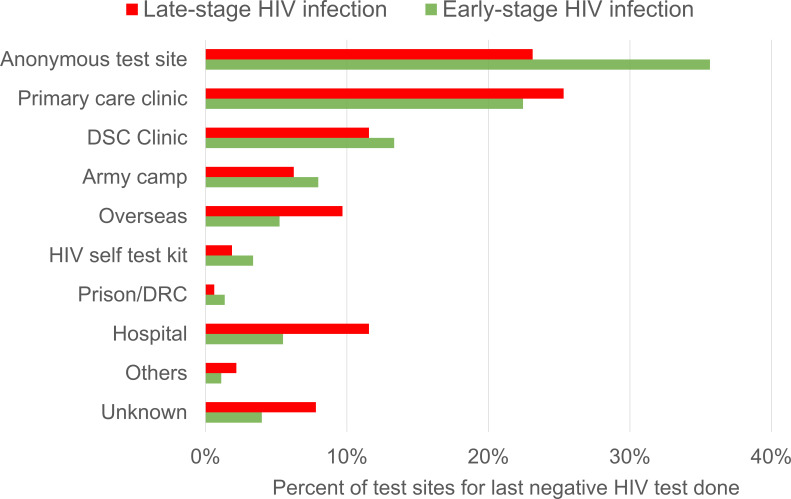

Popular test sites for HIV-positive persons with previous HIV tests were anonymous test sites (32.1%), primary care clinics (23.3%) and the Department of STI Control Clinic, a specialist outpatient clinic for the diagnosis, treatment and control of STIs (12.8%). The median duration from the last negative test to HIV diagnosis was 1.5 years (IQR 0.7–2.9) at anonymous test sites, compared with 2.5 years (IQR 1.2–5.2) at other test sites (p<0.0005).

About 49.4% of the 360 HIV-positive persons who previously tested negative at anonymous test sites were subsequently diagnosed with HIV via voluntary outpatient screening, while the rest were diagnosed via medical care or routine programmatic HIV screening. About 79.4% of these persons were diagnosed at early-stage of HIV infection. The proportion last tested negative at anonymous test sites was significantly higher in HIV-positive persons diagnosed at early-stage of HIV infection than those diagnosed at late-stage (35.7% vs 23.1%) (p<0.0005) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution (%) of test sites of sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons for their last negative HIV test result prior to diagnosis by stage of HIV infection at diagnosis in Singapore, 2012–2017. DRC, drug rehabilitation centre; DSC, Department of STI Control; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

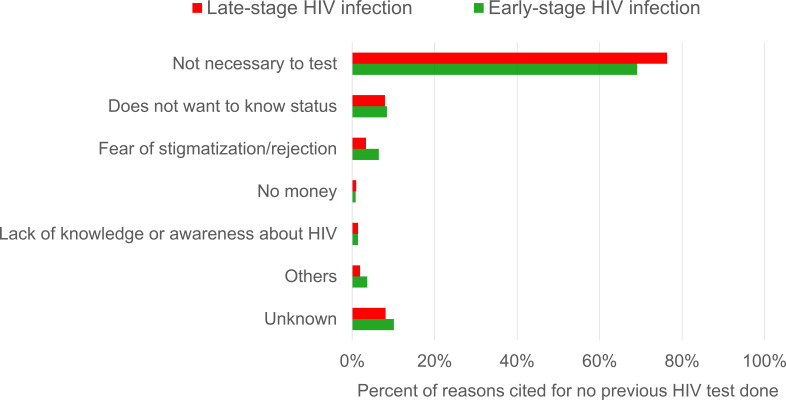

The most common reason cited by HIV-positive who did not have any previous HIV testing prior to diagnosis was ‘not necessary to test’ (73.7%), followed by ‘does not want to know status’ (8.1%) and ‘fear of stigmatisation/rejection’ (4.5%). There was a significantly higher proportion of HIV-positive diagnosed at late-stage of HIV infection (76.3%) who cited ‘not necessary to test’ compared with those diagnosed early (69.1%) (p=0.01) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution (%) of reasons for no previous HIV test prior to diagnosis among sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons by stage of HIV infection at diagnosis in Singapore, 2012–2017.

Factors associated with no previous HIV testing

Four factors were independently associated with no previous HIV testing among HIV-positive persons diagnosed at late-stage of infection: older age at HIV diagnosis (≥55 years vs 15–24 years), lower educational level (vs university degree or higher), detection via medical care (vs voluntary screening) and HIV infection via heterosexual transmission (vs homosexual/bisexual transmission) (table 2). The following six factors were independently associated with no previous HIV testing among HIV-positive persons diagnosed at early-stage: older age at HIV diagnosis (≥45 years vs 15–24 years), women, Malays (vs Chinese), lower educational level (vs university degree or higher), detection via medical care and routine programmatic HIV screening (vs voluntary screening) and HIV infection via heterosexual transmission (vs homosexual/bisexual transmission) (table 3).

Table 2.

Proportion and ORs of absence of previous HIV testing in sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons cases diagnosed at late-stage HIV infection in Singapore, 2012–2017

| Characteristic | Without previous HIV testing (%) | Univariable model | Multivariable model | ||||

| cOR | (95% CI) | P value | aOR | (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | <0.0005 | <0.0005 | |||||

| 15–24 | 44.4 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| 25–34 | 38.4 | 0.78 | (0.34 to 1.78) | 0.552 | 0.76 | (0.31 to 1.85) | 0.546 |

| 35–44 | 49.6 | 1.23 | (0.55 to 2.73) | 0.61 | 0.89 | (0.38 to 2.11) | 0.794 |

| 45–54 | 73.6 | 3.48 | (1.56 to 7.76) | 0.002 | 1.97 | (0.83 to 4.68) | 0.126 |

| 55–64 | 83.6 | 6.37 | (2.72 to 14.92) | <0.0005 | 2.71 | (1.07 to 6.85) | 0.035 |

| >65 | 93.4 | 17.81 | (5.02 to 63.20) | <0.0005 | 6.14 | (1.60 to 23.50) | 0.008 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 62.8 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Female | 83.1 | 2.91 | (1.58 to 5.37) | 0.001 | |||

| Ethnic group | 0.087 | ||||||

| Chinese | 65.6 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Malay | 60.3 | 0.8 | (0.57 to 1.12) | 0.194 | |||

| Indian | 73.3 | 1.44 | (0.73 to 2.84) | 0.29 | |||

| Others | 50 | 0.52 | (0.27 to 1.01) | 0.053 | |||

| Marital status | <0.0005 | ||||||

| Single | 51.7 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Married | 82.2 | 4.3 | (3.02 to 6.13) | <0.0005 | |||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 81.3 | 4.05 | (2.58 to 6.35) | <0.0005 | |||

| Educational level* | <0.0005 | 0.039 | |||||

| No formal/primary | 88.9 | 14.45 | (6.87 to 30.39) | <0.0005 | 3.23 | (1.40 to 7.46) | 0.006 |

| Secondary | 66.9 | 3.65 | (2.09 to 6.37) | <0.0005 | 1.51 | (0.81 to 2.84) | 0.195 |

| Post-secondary/diploma | 63.6 | 3.16 | (1.98 to 5.04) | <0.0005 | 1.75 | (1.03 to 2.96) | 0.038 |

| University degree or higher | 35.6 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Occupational type* | <0.0005 | ||||||

| Professional/executive | 49 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Administrative/service | 58.7 | 1.48 | (1.05 to 2.07) | 0.023 | |||

| Blue-collar worker | 84.5 | 5.66 | (3.58 to 8.95) | <0.0005 | |||

| Unemployed | 80.4 | 4.27 | (2.03 to 8.98) | <0.0005 | |||

| Others | 68.2 | 2.23 | (1.31 to 3.81) | 0.003 | |||

| Mode of detection | <0.0005 | <0.0005 | |||||

| Voluntary screening | 26.7 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Medical care | 72.7 | 7.3 | (4.40 to 12.10) | <0.0005 | 4.15 | (2.35 to 7.33) | <0.0005 |

| Routine programmatic HIV screening† | 54.1 | 3.23 | (1.82 to 5.71) | <0.0005 | 1.9 | (0.99 to 3.65) | 0.054 |

| Others | 36.4 | 1.57 | (0.67 to 3.68) | 0.304 | 0.89 | (0.34 to 2.34) | 0.819 |

| Mode of sexual transmission | |||||||

| Homosexual/bisexual | 43.1 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Heterosexual | 81.3 | 5.76 | (4.32 to 7.67) | <0.0005 | 3.46 | (2.50 to 4.80) | <0.0005 |

| Type of sexual partners* | <0.0005 | ||||||

| Regular only | 74.5 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Regular and casual only | 52.9 | 0.39 | (0.24 to 0.63) | <0.0005 | |||

| Sex workers and social escorts | 78.8 | 1.27 | (0.75 to 2.14) | 0.369 | |||

| History of STIs | |||||||

| Yes | 57.7 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| No | 65.8 | 1.41 | (1.00 to 1.98) | 0.048 | |||

*Missing data were imputed.

†Routine programmatic HIV screening includes screening programmes for those with STIs, hospital inpatients and those identified through contact tracing.

aOR, adjusted OR; cOR, crude OR; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Table 3.

Proportion and ORs of absence of previous HIV testing in sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons diagnosed at early-stage HIV infection in Singapore, 2012–2017

| Characteristic | Without previous HIV testing (%) | Univariable model | Multivariable model | ||||

| cOR | (95% CI) | P value | aOR | (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | <0.0005 | <0.0005 | |||||

| 15–24 | 23 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| 25–34 | 20.4 | 0.86 | (0.57 to 1.29) | 0.453 | 1.07 | (0.69 to 1.67) | 0.758 |

| 35–44 | 23.5 | 1.02 | (0.67 to 1.56) | 0.909 | 1.07 | (0.67 to 1.71) | 0.769 |

| 45–54 | 44.1 | 2.64 | (1.71 to 4.08) | <0.0005 | 2.26 | (1.38 to 3.73) | 0.001 |

| 55–64 | 62.4 | 5.53 | (3.20 to 9.56) | <0.0005 | 3.18 | (1.70 to 5.96) | <0.0005 |

| >65 | 90 | 30.06 | (6.73 to 134.30) | <0.0005 | 13.17 | (2.80 to 62.03) | 0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 27.5 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Female | 62.1 | 4.32 | (2.58 to 7.22) | <0.0005 | 2.07 | (1.13 to 3.78) | 0.018 |

| Ethnic group | 0.002 | 0.004 | |||||

| Chinese | 26.7 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Malay | 36.8 | 1.6 | (1.18 to 2.17) | 0.002 | 1.76 | (1.24 to 2.50) | 0.002 |

| Indian | 40.3 | 1.85 | (1.14 to 2.99) | 0.012 | 1.21 | (0.70 to 2.08) | 0.499 |

| Others | 22.7 | 0.81 | (0.39 to 1.66) | 0.561 | 0.53 | (0.24 to 1.18) | 0.119 |

| Marital status | <0.0005 | ||||||

| Single | 22.5 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Married | 52.5 | 3.8 | (2.77 to 5.22) | <0.0005 | |||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 56.5 | 4.47 | (2.71 to 7.37) | <0.0005 | |||

| Educational level* | <0.0005 | <0.0005 | |||||

| No formal/primary | 63 | 8.81 | (4.52 to 17.15) | <0.0005 | 2.22 | (1.04 to 4.75) | 0.04 |

| Secondary | 53 | 5.85 | (3.47 to 9.87) | <0.0005 | 2.8 | (1.56 to 5.04) | 0.001 |

| Post-secondary/diploma | 27.2 | 1.94 | (1.30 to 2.90) | 0.001 | 1.15 | (0.74 to 1.79) | 0.538 |

| University degree or higher | 16.2 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Occupational type* | <0.0005 | ||||||

| Professional/executive | 21.4 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Administrative/service | 28 | 1.43 | (1.02 to 2.00) | 0.038 | |||

| Blue-collar worker | 61.6 | 5.88 | (3.67 to 9.43) | <0.0005 | |||

| Unemployed | 36.8 | 2.14 | (1.05 to 4.37) | 0.037 | |||

| Others | 26 | 1.29 | (0.86 to 1.93) | 0.223 | |||

| Mode of detection | <0.0005 | <0.0005 | |||||

| Voluntary screening | 12.6 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Medical care | 45.5 | 5.81 | (3.96 to 8.53) | <0.0005 | 3.66 | (2.39 to 5.59) | <0.0005 |

| Routine programmatic HIV screening† | 34 | 3.58 | (2.49 to 5.16) | <0.0005 | 2.66 | (1.79 to 3.95) | <0.0005 |

| Others | 20.7 | 1.81 | (0.99 to 3.32) | 0.053 | 1.41 | (0.74 to 2.70) | 0.294 |

| Mode of sexual transmission | |||||||

| Homosexual/bisexual | 19.6 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | ||

| Heterosexual | 53 | 4.6 | (3.52 to 6.02) | <0.0005 | 2.17 | (1.55 to 3.04) | <0.0005 |

| Type of sexual partners* | <0.0005 | ||||||

| Regular only | 36 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| Regular and casual only | 23.3 | 0.54 | (0.37 to 0.78) | 0.001 | |||

| Sex workers and social escorts | 47.8 | 1.63 | (1.06 to 2.48) | 0.025 | |||

| History of STIs | |||||||

| Yes | 25.6 | 1 | Referent | ||||

| No | 31 | 1.31 | (0.99 to 1.73) | 0.06 | |||

*Missing data were imputed.

†Routine programmatic HIV screening includes screening programmes for those with STIs, hospital inpatients and those identified through contact tracing.

aOR, adjusted OR; cOR, crude OR; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Discussion

This study found that slightly less than half of the sexually transmitted HIV-positive persons reported no previous HIV test prior to diagnosis. Close to two-thirds of the HIV-positive persons diagnosed at late-stage HIV infection did not have previous HIV tests, more than twice the proportion among those diagnosed early (29.4%). The median duration from the last negative test to HIV diagnosis was 3.8 years among HIV-positive persons with late-stage HIV infection, double that of those diagnosed early. These findings highlight the importance of regular HIV testing for early diagnosis so as to secure optimal outcomes in the HIV care cascade.

Anonymous test sites were the most popular among HIV-positive persons for their last negative HIV test prior to diagnosis (figure 2). At-risk individuals who go to anonymous test sites are more likely to have HIV testing on a regular basis or at a shorter intertest interval, as reflected by the higher proportion of HIV-positive persons diagnosed early (79.4%) among those who were last tested negative at these test sites and the shorter median duration from the last negative test to HIV diagnosis compared with other test sites (1.5 vs 2.5 years). To encourage voluntary outpatient screening by reducing the stigma associated with seeking HIV testing, the Ministry of Health introduced anonymous HIV testing using oral-fluid or blood-based rapid HIV test kits at selected GP clinics and test sites run by community-based organisations in August 2007.10 Anonymous testing offers privacy and confidentiality that encourages more people to check their HIV status. There are now ten anonymous HIV test sites in Singapore, comprising nine GP clinics and a test site operated by Action for AIDS (AfA), a local non-governmental HIV/AIDS community-based organisation.11 To make voluntary HIV screening more accessible and convenient in Singapore, AfA launched the first Mobile Testing and Counselling Service which provides anonymous HIV and syphilis testing on wheels in December 2011.12 The number of HIV tests conducted at anonymous test sites increased by 25% from 13 900 in 2013 to 17 400 in 2017.13

Four common risk factors were associated with no previous HIV testing in multivariable analyses in both early and late stages of HIV infection at diagnosis: older age, lower educational level, detection in the course of medical care and heterosexual transmission (tables 2 and 3). Older persons may perceive themselves to be at lower risk of HIV infection, or may be less aware of HIV and more reluctant to undergo HIV testing. Lower educational level was an impediment in having HIV tests among men having sex with men (MSM) in some studies.14–17 HIV testing is most likely to be initiated only during medical care due to clinical suspicion of HIV infection based on disease presentations or risk profiles.5 In a local study of HIV-positive men, those of older age (≥30 years) at diagnosis and infected via heterosexual transmission were more likely to be detected through medical care as opposed to voluntary screening.18 Our finding indicated the need to increase HIV testing rates among persons at high risk of HIV infection with these epidemiological risk factors.

The proportion of persons infected with HIV via heterosexual transmission with no previous HIV test prior to diagnosis (70.1%) was about 2.5 times that of those infected via homosexual/bisexual transmission (27.5%). Hence, they were also less likely to have recent HIV infection (RHI) at diagnosis, as shown in a local study in which the proportion of RHI was significantly lower in heterosexual men than in MSM (11.1% vs 23.4%).19 Similarly, in the USA, heterosexuals at high risk are known to have lower testing frequency than other groups such as MSM.20 According to a systematic review of 19 studies that evaluated behavioural preventive interventions in low-income and middle-income countries, heterosexual men remained under-represented in HIV prevention efforts.21 In Singapore, the outreach programme run by AfA includes edutainment shows, regular condom and collateral distributions to heterosexuals who engage in high-risk sexual activities at venues they frequent, so as to increase their knowledge about HIV/STIs and preventive methods, and encourage more voluntary testing.22

In a separate analysis among cases diagnosed at early-stage HIV infection, women were less likely to have previous HIV testing prior to their diagnosis. HIV/AIDS cases diagnosed in Singapore are predominantly men with male to female ratio of 9:1. Women who believe that their sexual partners are faithful in the relationship are less likely to perceive themselves to be at risk of HIV infection. Among HIV-positive persons who had been diagnosed early, those of Malay ethnicity were more likely not to have had the previous testing for HIV prior to diagnosis when compared with ethnic Chinese. This could be due to HIV-related stigma arising from the influence of culture and religiosity. In Malaysia, a study conducted in 2012–2013 found that Malay Muslim HIV patients who disclosed their illness had significantly higher total stigma level than the non-disclosure group.23

As this study identified a significant proportion of late-stage HIV infection (63.9%) among HIV-positive persons who did not have previous HIV tests, healthcare providers should have a higher index of suspicion for HIV infection among at-risk groups, and recommend an HIV test where appropriate.24 In a study on HIV testing behaviour among HIV-uninfected, at-risk adolescents and those who were HIV-infected in the USA, 67% of the high-risk group and 53% of the HIV-infected group cited recommendation by healthcare professionals as a reason to undergo HIV testing.25 In a study among heterosexuals at high risk of HIV infection in New York City, facilitators of past-year HIV testing common to both genders included STI testing or STI diagnosis, peer norms supporting HIV testing and HIV testing access.26 Independent factors associated with regular HIV testing behaviour among MSM in China included perceived risk, greater knowledge of HIV testing and having an STI test in the past year.27 Individuals, especially those at high risk of STIs and HIV, would benefit from having better knowledge about HIV and the symptoms related to acute or advanced HIV infection, as well as the benefits of early diagnosis and linkage to care.24

HIV infection has a long clinical latency period during which infected individuals may show no symptoms. Relying on symptom-based HIV diagnosis would lead to late diagnosis, missing the opportunity of early detection.28 29 Hence, it is crucial to provide a system that can support HIV testing with minimal inconvenience, so as to encourage greater uptake of HIV screening among those who are at risk regardless of whether they are asymptomatic or symptomatic. In our study, about three-quarters of HIV-positive who had no previous HIV testing deemed that it was ‘not necessary to test’, and the proportion was significantly higher among those with late-stage than early-stage HIV infection at diagnosis (76.3% vs 69.1%) (figure 3), which likely represents a lack of knowledge of their own risk of HIV infection despite ongoing risk behaviour. The Singapore Health Promotion Board has been working with partner organisations to conduct programmes and campaigns targeted at high-risk individuals to urge them to go for early and regular HIV testing.30 Various educational programmes on HIV prevention and management are conducted using a lifestyle approach in order to reach out to at-risk individuals through social settings.

There are several limitations in this study. Our study used the epidemiological data collected in the National HIV Registry which was not designed to investigate determinants of previous HIV testing. Hence, not all potential confounding factors could be included in our study, and information on drivers and barriers of HIV testing was unavailable. Qualitative studies are needed to delineate the processes underlying different patterns of testing in local context.31 As testing-related information was ascertained based on self-reporting by HIV-positive persons, some extent of misclassification due to recall bias could not be avoided.

In conclusion, the proportion of HIV-positive persons who had never been tested for HIV prior to HIV diagnosis was 45.1%. Our study findings highlight the need for concerted efforts to raise awareness of the importance of early and regular HIV testing and boost its uptake by making HIV testing more accessible and less discriminatory, particularly among the high-risk groups in Singapore.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Singapore National HIV Registry for extraction of the HIV epidemiological database, and providing the deidentified data for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LWA conceived the study, did statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors (LWA, MPHST, ICB, CSW, SA, VL, AC, YSL) contributed to data interpretation, revised the manuscript and approved the submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Research approval for this study was provided by the Ministry of Health, Singapore. As the data were collected under the Infectious Diseases Act and analyses were performed on an anonymised dataset, informed consent was not required for this study.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . 90–90–90—An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/90-90-90 [Accessed 27 Jul 2018].

- 2.Lee VJM. Where are we with 90-90-90 in Singapore? Webinar 2: update on HIV treatment and cure. panel presentation at the 12th Singapore AIDS Conference, 5 December 2020. Available: https://afa.org.sg/whatwedo/advocate/sac-12th-2020 [Accessed 18 Dec 2020].

- 3.Ministry of Health, Singapore . Update on the HIV/AIDS situation in Singapore 2019, 2020. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/infectious-disease-statistics/hiv-stats/update-on-the-hiv-aids-situation-in-singapore-2019-(june-2020) [Accessed 6 Dec 2020].

- 4.Cutter JL, Lim W-Y, Ang L-W, et al. HIV in Singapore – past, present, and future. AIDS Educ Prev 2004;16:110–8. 10.1521/aeap.16.3.5.110.35528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tey JSH, Ang LW, Tay J, et al. Determinants of late-stage HIV disease at diagnosis in Singapore, 1996 to 2009. Ann Acad Med Singap 2012;41:194–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadborn TR, Delpech VC, Sabin CA, et al. The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals (England and Wales, 2000-2004). AIDS 2006;20:2371–9. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801138f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang LW, Tey SH, James L. Determinants of late-stage human immunodeficiency virus infection at first diagnosis. Singapore Epidemiol News Bull 2008;34:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health, Singapore . Infectious diseases act. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/policies-and-legislation/infectious-diseases-act [Accessed 31 Aug 2020].

- 9.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest - non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 2012;28:112–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HealthHub, Singapore . Get tested for HIV in minutes, 2018. Available: https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/371/get_tested_HIV_in_minutes [Accessed 4 May 2019].

- 11.Zhang Y, Kurupatham L, Badaruddin H, et al. Evaluation of the HIV surveillance system in Singapore. Singapore Epidemiol News Bull 2016;42:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Action for AIDS, Singapore . Annual report 2011. Available: https://afa.org.sg/portfolio-item/annualreport2011/ [Accessed 1 Jul 2021].

- 13.Ministry of Health, Singapore . Communicable diseases surveillance in Singapore 2017. Singapore: Communicable Diseases Division, Ministry of Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Pan X, Ma Q, et al. Prevalence of prior HIV testing and associated factors among MSM in Zhejiang Province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1152. 10.1186/s12889-016-3806-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JW, Horvath KJ. Factors associated with regular HIV testing among a sample of US MSM with HIV-negative main partners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:417–23. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a6c8d9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brito AM, Kendall C, Kerr L, et al. Factors associated with low levels of HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Brazil. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130445. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.den Daas C, Doppen M, Schmidt AJ, et al. Determinants of never having tested for HIV among MSM in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009480. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ang LW, Tey SH, James L. HIV-positive cases detected during medical care versus voluntary HIV screening in Singapore – how are they different? Singapore Epidemiol News Bull 2009;35:52–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang LW, Low C, Wong CS, et al. Epidemiological factors associated with recent HIV infection among newly-diagnosed cases in Singapore, 2013-2017. BMC Public Health 2021;21:430. 10.1186/s12889-021-10478-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenness SM, Murrill CS, Liu K-L, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing among high-risk heterosexuals. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:704–10. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ab375d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Townsend L, Mathews C, Zembe Y. A systematic review of behavioral interventions to prevent HIV infection and transmission among heterosexual, adult men in low-and middle-income countries. Prev Sci 2013;14:88–105. 10.1007/s11121-012-0300-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Action for AIDS, Singapore . HSO: heterosexual outreach. Available: https://afa.org.sg/whatwedo/educate/hso/ [Accessed 30 Jun 2021].

- 23.Fadzil NA, Othman Z, Mustafa M. Stigma in Malay patients with HIV/AIDS in Malaysia. Int Medical J 2016;23:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darling KE, Hachfeld A, Cavassini M, et al. Late presentation to HIV care despite good access to health services: current epidemiological trends and how to do better. Swiss Med Wkly 2016;146:w14348. 10.4414/smw.2016.14348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy DA, Mitchell R, Vermund SH, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing among HIV-positive and HIV-negative high-risk adolescents: the reach study. Reaching for excellence in adolescent care and health. Pediatrics 2002;110:e36. 10.1542/peds.110.3.e36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwadz M, Cleland CM, Kutnick A, et al. Factors associated with recent HIV testing among heterosexuals at high risk for HIV infection in New York City. Front Public Health 2016;4:76. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Bromberg DJ, Khoshnood K, et al. Factors associated with regular HIV testing behavior of MSM in China: a cross-sectional survey informed by theory of triadic influence. Int J STD AIDS 2020;31:1340–51. 10.1177/0956462420953012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rüütel K, Lemsalu L, Lätt S, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in people diagnosed with HIV, Estonia, 2014 to 2015. Euro Surveill 2019;24. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.15.1800382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inghels M, Niangoran S, Minga A, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing among newly diagnosed HIV-infected adults in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185117. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Health, Singapore . Update on the HIV/AIDS situation in Singapore 2019, 2020. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/infectious-disease-statistics/hiv-stats/update-on-the-hiv-aids-situation-in-singapore-2019-(june-2020) [Accessed 30 Jun 2021].

- 31.Tan RKJ, Kaur N, Chen MI-C, et al. Developing a typology of HIV/STI testing patterns among gay, bisexual, and Queer men: a framework to guide interventions. Qual Health Res 2020;30:610–21. 10.1177/1049732319870174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050133supp001.pdf (41.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.