Abstract

This national professional society guidance lays out operational and ethical principles for decision-making during a pandemic, in the immediate context of COVID-19 in the early 2020 surge iteration but with potential ongoing relevance. It identifies the different phases of a pandemic and the implications for capacity and mutual aid within a national healthcare system, and introduces a revised CRITCON-PANDEMIC framework for shared operational responsibilities and clinical decision-making. Usual legal and ethical frameworks should continue to apply while capacity and mutual aid are available (CRITCON-PANDEMIC levels 0-3); clinicians should focus on current clinical needs and should not treat patients differently because of anticipated future pressures. In conditions of resource limitation (CRITCON-PANDEMIC 4), a structured and equitable approach is necessary and an objective Decision Support Aid is proposed. In producing this guidance, we emphasise that all patients must be treated with respect and without discrimination, because everyone is of equal value. The guidance has been put together with input from patient and public groups and aims to provide standards that are fair to everyone. We acknowledge that COVID-19 is a new disease with a partial and evolving knowledge base, and aim to provide an objective clinical decision-making framework based on the best available information. It is recognised that a factual assessment of likely benefit may take into account age, frailty and comorbidities, but the guidance emphasises that every assessment must be individualised on a balanced, case by case, basis and may inform clinical judgement but not replace it. The effects of a comorbidity on someone's ability to benefit from critical care should be individually assessed. Measures of frailty should be used with care, and should not disadvantage those with stable disability.

Keywords: Decision making, pandemic, triage, ethics, critical care

Principles

The primary aim of this guidance is to ensure that all patients get appropriate treatment during a pandemic. It is written in the context of COVID-19 and in the operational setting of the UK National Health Service (NHS). The immediate clinical guidance is intended to be consistent with national guidance issued by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), British Medical Association (BMA) and General Medical Council (GMC).1–3 Where clinicians can document that they have considered and applied national professional guidance, including the present document, this will provide strong evidence that they have acted lawfully and according to their professional obligations.

If we are to minimise the harm that the virus can cause, patients should receive the interventions that are most likely to benefit them. The first responsibility of clinical teams is to assess what treatment is likely to provide benefit to the patient, taking into account the best available opinion on factors that predict this and applying it to the specific situation of the patient they are treating. COVID-19 is a new disease and data to assist clinical teams assessing what interventions are likely to benefit patients are now emerging. Some of the tools and discussion in this guidance are specific to COVID-19, but the ethical principles apply to all patients including non-infected patients who may be indirectly affected by the pandemic due to changes in delivery of normal services.

A decision on the appropriateness of a specific treatment is not concerned with whether patients will receive treatment, but with what treatment should be offered. If it is decided that one treatment plan is not appropriate, other more appropriate treatments will be started or continued. For some patients End-of-Life Care is appropriate, either because that is their preferred option or because the clinical team has assessed their prognosis and has concluded that an intervention will not bring them benefit. Such decisions are based on the patient's circumstances and are independent of resource availability.

Decision making should be consistent with current ethical and legal frameworks.4 Patients' preferences in relation to the intrusiveness of treatment that is acceptable to them must be taken into account, through shared discussion with the patient when their condition allows, and otherwise with their family or other advocate. They should be supported to record their wishes around treatment escalation if their condition deteriorates, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation (which can be undignified and intrusive with limited chances of success). However, patients or their representatives are not entitled to demand care that is clinically inappropriate. Whenever possible, it is important to engage with patients and families early in the course of the illness, as this allows patients greater autonomy before they become too ill to fully participate.

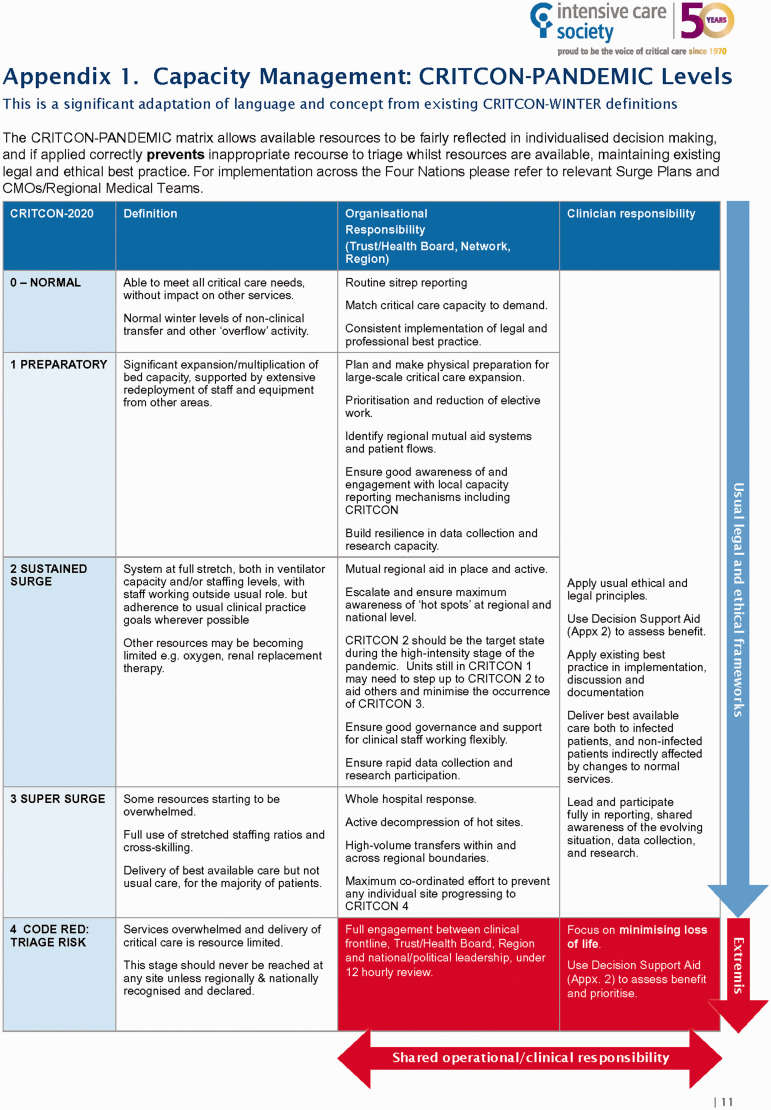

This guidance places ethical and clinical decision-making within the framework of an operational organisational response, described under a modified version of the UK CRITCON scoring system that was first devised and implemented during the H1N1 (2009) pandemic.5 This describes critical care unit pressures and capacity in terms of organisational stretch and variance from usual practice rather than raw bed occupancy. The present guidance emphasises that usual pre-existing ethical and clinical decision-making models and protocols will continue to be applied , other than in the extreme circumstances arising under CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 as described in Figure 1. It also emphasises that all decision-makers, whether clinical or managerial, are obliged to communicate and act so as to avoid CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 arising at any individual hospital. To date, there has proved to be capacity within the NHS.

Figure 1.

Capacity management: CRITCON-PANDEMIC levels.

The guidance necessarily recognises, however, that there is precedent for the use of objective clinical criteria in specific and limited circumstances, both in normal circumstances6 and during national emergencies.7 It also recognises that should CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 be engaged clinicians will need to act according to national ethical and clinical decision-making criteria, and provides the necessary clinical criteria in relation to allocation of limited resources between patients. As understanding of COVID-19 evolves, the clinical criteria may be adjusted.

There is clear demand for such clinical guidance in conjunction with associated ethical guidance. It is intended to provide practical support and clear protocols for clinicians to apply and to support them accordingly. It promotes understanding by the public as to the clinical and ethical considerations that will be applied. It may be revised as part of the continuing review of international and national data as to COVID-19 and wider contributions from other stakeholders.

A structured approach to assessing when critical care is an appropriate option

Some treatments, such as critical care, are never certain to bring benefits to any one individual and should be approached as a ‘trial of therapy’. Admission for critical care is appropriate if the patient can be reasonably expected to survive and receive sustained benefit. Continuation should be considered in the light of patient response. The desired or likely outcomes of treatment should be discussed at the start. There should be regular review. If the goals are not being achieved, other treatment options should be considered, including transition to end of life care.8,9

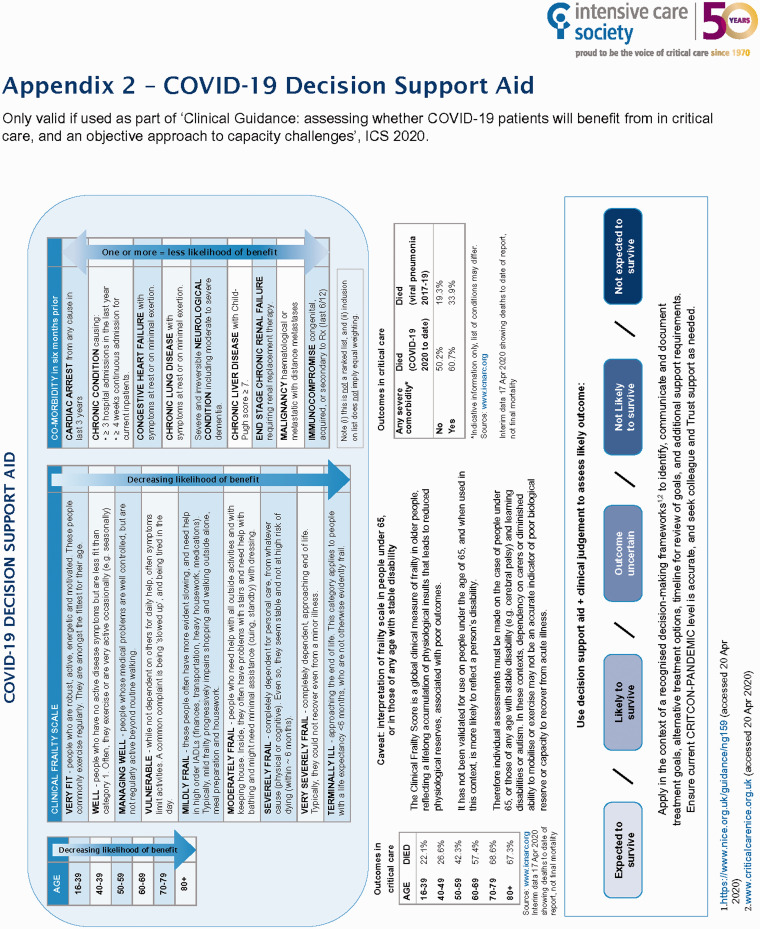

The clinical support materials included in this document are designed to operationalise and support existing guidance, and to make the best available information accessible to clinicians in a clear and straightforward way to support their professional judgment. The clinical support materials include a Decision Support Aid which summarises key data on factors that are likely to impact on the chances of patients surviving to be discharged from critical care. They should ensure that there is a comprehensive, individualised assessment of each patient.

At all stages short of in extremis resource limitation (CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4), they should be used only for individualised decision-making, independent of resource. If a situation of limited resources is reached (CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4, agreed at regional or national level and only after maximum escalation and mutual aid), then they may come into use as an appropriate objective clinical way to individually assess and allocate the resource according to those patients most likely to benefit. This approach is consistent with the published national ethical guidance and is directed at minimising the overall loss of life. It is emphasised that at no stage is a numeric score or threshold applied: each patient will continue to be considered as an individual.

Patients' underlying health may significantly affect their ability to benefit. It is important to assess this in a non-discriminatory way. In a clinically appropriate context, frailty (accumulated biological damage and diminished reserve) and age may be relevant indications of capacity to benefit from critical care and other invasive therapies. They must be objectively and individually assessed as part of wider clinical judgement, taken within the context of a wider assessment of health over the previous few months. Although there are established tools to characterise frailty, care should be taken to make individual assessments in the event of stable disability, developmental disorders or established stable long-term organ support (e.g. respiratory or renal). These are discussed further below.

The explanation of the principles within this framework has been informed by the work from the DHSC Moral and Ethical Advisory Group,10 medical Royal Colleges, the British Medical Association, clinical specialist societies and local guidance within the NHS. Our aim is to ensure that all patients are treated with respect, as everyone matters equally.

Critical care capacity and decision-making: Organisational and individual responsibilities

To date, and reflecting a strategy of significantly increasing capacity, CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 has not been reached at any individual hospital, although at the cost of significant adaptation to usual standards of staffing and equipment and with so far unknown impact on outcomes. The demands made of individual hospitals have varied regionally, with the possibility of further secondary hot spots after initial control or in the event of further waves of pandemic. The immediate guidance addresses the possibility of overwhelming demand in future.

It is important that while there is capacity and access, usual decision-making should apply equitably, and this document aims to reinforce that. Patients should not suffer either from geographical inequality of access, or from premature and incorrect resort to resource-limited decision-making at individual sites. It is equally important that frontline clinicians are fully engaged and supported by their Trusts, Regional Medical Teams and wider NHS, so that no one is avoidably put in a position of clinical decisions being affected by local resource limitation when this can be effectively addressed by NHS mutual aid. Common and agreed national guidance is required to assess, manage and share knowledge of critical care capacity by each of these parties.

The original CRITCON classification for Winter Influenza Surge was designed in 2009 to describe pressure on intensive care units in a qualitative and easy to understand way.5 It is explicitly designed to represent the level of “stress” in the system, and any deviation required from usual practice, reflecting innovative practices and flexible expansion. It is based on the actual clinical capacity of the system as assessed on the ground, rather than simple bed and occupancy numbers or other quantitative measures – which may not adequately reflect available staffing, equipment or consumables. Should other critical care interventions be found to be beneficial in the context of COVID-19 – such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or renal replacement therapy (RRT) – and dedicated beds are needed for those treatments, they should be included in the assessment of bed capacity to define the CRITCON status.

The CRITCON-PANDEMIC matrix (Figure 1) applies the 2009–2014 criteria to the specific COVID-19 pandemic. Obligations and expectations of organisations and individuals are reflected at each level of demand on resources in an objective and practical form. The central objective is to define and co-ordinate a response across the NHS such that individual Trusts maintain levels up to CRITCON-PANDEMIC-2 (‘Sustained Surge’) throughout the pandemic. Meeting this objective would mean that CRITCON-PANDEMIC levels 3 and (most particularly) 4 are not engaged.

In order to achieve this, a deteriorating CRITCON-PANDEMIC level must lead to a whole-hospital, Network/ODN, Regional and (when necessary) national response with the aim of returning critical care to lower levels of CRITCON as quickly as possible, while ensuring safe and equitable care for all during times of peak demand. Especially important is the explicit use of maximal mutual aid to prevent any hospital reaching CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4, when there is a risk of resource-limited decisions arising.

Individual clinicians and teams have a vital part to play in this process by ensuring that they are fully engaged with data reporting processes and have escalated concerns and information within their organisations rapidly and reliably. The CRITCON-PANDEMIC reporting system is designed to supplement numeric reporting systems and be clinician-friendly, accurate and easily interpretable.

The declaration of CRITCON-PANDEMIC level for a given critical care unit remains the responsibility of the overseeing hospital group/healthcare organisation (in the UK: the relevant NHS Trust/Health Board, in coordination with regional and national organisations including the Critical Care Networks and NHS England). The operational details of accurately reporting capacity within a given region are an NHS command chain responsibility, and we suggest that the responsibility for accurately assessing unit strain through CRITCON-PANDEMIC and applying mutual aid to minimise the duration of CRITCON-PANDEMIC-3 and prevent CRITCON- PANDEMIC-4 should rest with the relevant Regional Medical Director.

Ethical practice when critical care capacity is stretched (CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 only)

Clinical teams should focus on current clinical demands and available resources. They should not, at any stage of escalation, treat patients differently because of anticipated future pressures, since at every stage short of CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4, mutual aid of some form should be available. If they consider that they do not have the resources to provide the care that they believe would be most likely to benefit the patient, they should consider whether that care may reasonably be provided at another site (if the patient's condition would enable a transfer) within their regional network or nationally, or by distribution of resources from another site. This assessment should involve clinical colleagues and senior operational management, and it should be borne in mind that under these circumstances and with appropriate escalation, access to extraordinary transport and other measures are likely to be available, under civil powers or military assistance to same.

Individual clinical staff should not be required to take decisions on potentially life-sustaining treatments alone under conditions of resource limitation. This is an unfair burden to ask any individual to bear. Employers should take steps to support ethical decision-making, including through clinical ethics committees and psychological support.

Consistent with previously published ethical guidance, clinical decisions must be taken according to the assessment of which patients are most likely to benefit from treatment applying limited resources. This approach is both transparent and objective. It does not create arbitrary clinical thresholds in relation to any individual patient, but does ensure that limited resources are directed at achieving the highest levels of survival across the population group of patients.

It is recognised that in critical care clinical decision-making sometimes requires an immediate decision without the opportunity for consultation. Where practicable, however, all clinical decisions under the extreme circumstances engaged under CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 should be taken collectively by a team of qualified practitioners applying the relevant ethical and clinical guidance, and – where necessary and practicable – reference made by them to local ethical guidance committees. The rationale for such decisions should be clearly documented, including any process of consultation.11

Use of this guidance

It is important to use all materials in the context of the written narrative above, and in the context of clinical judgement and individualised decision making.

In Figure 1, the CRITCON-PANDEMIC operational responsibility matrix sets decision-making into an operational escalation context and recognises that individualised decision making, and existing recognised best practice, should be maintained through escalating levels of demand.

Effective expansion and sharing of resources should ensure that conditions of triage should not need to be considered until a situation of regional and national extremis. This point must be determined externally by the declaration of CRITCON-PANDEMIC-4 by a given Trust in coordination with regional and national structures, and not determined by an individual clinician. Even at this extreme point there should be an equitable and transparent decision-making process.

Figure 2 is a Decision Support Aid to guide prognostication in a resource-limited setting. Patients' comorbidities, frailty and age may be relevant indications of capacity to benefit from critical care and other invasive therapies, as outlined by NICE.4 This graphic summarises available data on COVID-19, and highlights those factors that are known to decrease the benefits of critical care. Decision-making based on prognostic indicators should take place in a recognised framework, including peer discussion and use of external tools and guidance.

Figure 2.

COVID-19 decision support aid.

The first iteration for the Decision Support Aid was developed by a UK respiratory critical care expert group. It was based on a comprehensive review of the available literature and data. Further relevant data are progressively becoming available and are reflected in the guidance. The guidance is based on continuing review and consultation with an extended, multi-trust group of acute medicine and respiratory clinicians, including from Scotland. Available outcome data have been drawn from the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC), while acknowledging that these are constrained by the evolving nature of the source data emerging during the pandemic, and potential biases arising from this.

There are some important caveats to the use of clinical frailty indices. Frailty is a distinctive health state related to the ageing process, in which multiple body systems gradually lose their in-built reserves. Around 10% of people aged over 65 years show evidence of frailty, rising to between a quarter and a half of those aged over 85.12 Frailty is assessed using proxy measures including the degree of home carer and other support required. These measures should not be routinely used to assess patients who may have good biological reserve to recover from acute illness have stable physical disabilities, learning disabilities or autism, or with long-term organ support needs (examples may include stable dialysis patients, or those needing long-term respiratory or other support for neurodisability, such as genetic muscle disease or cerebral palsy).

An individualised assessment of frailty in such cases should include clinical stability and rate of deterioration of functional status. The severity of chronic disease is important when considering the ability of such patients to recover from multiple organ failure and prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Patients receiving organ support for long-term conditions should be aware that they may not be admitted to the hospital where their care is usually delivered and therefore consideration should be given to formulating an Emergency Health Care Plan with patient participation.

Conclusion

This guidance lays out ethical principles and sets out a stepwise model for shared escalation with mutual aid between organisations in all phases of a pandemic, and provides a decision support aid which incorporates age, frailty and comorbidities in an objective way to support individualised decision-making. Using these together, clinicians and organisations should ensure that no patient is disadvantaged by an avoidable lack of access to critical care at any phase of pandemic; that patients are not treated differently in anticipation of future resource limitation; and that usual ethical frameworks apply. In extremis, prioritisation may be required to minimise the loss of life and to ensure that the best possible care is given to those can best benefit. The tools provided will support clinicians to continue to make individualised decisions, by consensus and against an objective framework.

Acknowledgements

This guideline has been endorsed by Royal College of Physicians (London), the Scottish Intensive Care Society, the Welsh Intensive Care Society, the All-Wales Trauma and Critical Care Network, the National Critical Care Networks of England, and Critical Care Network Northern Ireland. We are grateful to the members of the Intensive Care Society Legal and Ethical Advisory Group (LEAG) for their input into its development. The original CRITCON definition is credited to the NHS London H1N1 (2009) Pandemic Planning Group, with input from the North West London and Surrey Critical Care Networks.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

J Montgomery https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4592-0930

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians. Ethical dimensions of COVID-19 for frontline staff, www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/20726/download (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 2.British Medical Association. COVID-19 – ethical issues. A guidance note, and Statement/briefing about the use of age and/or disability in our guidance, www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/ethics/covid-19-ethical-issues (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 3.General Medical Council. Coronavirus: your frequently asked questions, www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-hub/covid-19-questions-and-answers (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 4.National Institute for Clinical Effectiveness. NICE COVID-19 rapid guideline: critical care in adults (NG159), www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng159 (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 5.North West London Critical Care Network (adapted and adopted by NHS England), www.londonccn.nhs.uk/managing-the-unit/capacity-escalation/critcon/ ( accessed 25 June 2020).

- 6.NHS Blood and Transplant, Introduction To Patient Selection and Organ Allocation Policies, NHSBT POLICY POL200/4.1, www.odt.nhs.uk/transplantation/tools-policies-and-guidance/policies-and-guidance/ (2017, accessed 12 June 2020).

- 7.National Blood Transfusion Committee. Guidance and triage tool for the rationing of blood for massively bleeding patients during a severe national blood shortage, www.transfusionguidelines.org/uk-transfusion-committees/national-blood-transfusion-committee/responses-and-recommendations (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 8.General Medical Council. Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making, www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/treatment-and-care-towards-the-end-of-life (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 9.Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Care at the end of life: a guide to best practice, discussion and decision-making in and around critical care, www.ficm.ac.uk/critical-futures-initiative/care-end-life (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 10.Moral and Ethical Advisory Group, www.gov.uk/government/groups/moral-and-ethical-advisory-group (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 11.NHS Elect. NICE Critical Care Guidelines, www.criticalcarenice.org.uk (accessed 12 June 2020).

- 12.British Geriatric Society. Introduction to Frailty, Fit for Frailty Pt.1, www.bgs.org.uk/resources/introduction-to-frailty (accessed 12 June 2020).