Abstract

Purpose:

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health care delivery and services around the world causing rapid changes to maternity care protocols and pregnant women to give birth with tight restrictions and significant uncertainties. There is a gap in evidence about expectant and new mothers' experiences with birthing during the pandemic. We sought to describe and understand pregnant and new mothers' lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic using authentic birth stories.

Study Design and Methods:

Using a narrative analysis framework, we extracted relevant YouTube birth stories using predetermined search terms and inclusion criteria. Mothers' birth stories were narrated in their second or third trimester or those who had recently given birth during the pandemic. Birth stories were analyzed using an inductive and deductive approach to capture different and salient aspects of the birthing experience.

Results:

N = 83 birth stories were analyzed. Within these birth stories, four broad themes and 13 subthemes were identified. Key themes included a sense of loss, hospital experiences, experiences with health care providers, and unique experiences during birth and postpartum. The birth stories revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic brought unexpected circumstances, both positive and negative, that had an impact on mothers' overall birthing experience.

Clinical Implications:

Results provided a detailed description of women's lived experience with giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maternity nurses should try to provide clear communication and compassionate patient-centered care to relieve women's anxieties about uncertain and unpredictable policy changes on COVID-19 as the pandemic continues to evolve.

Key words: Birth, COVID-19, Internet, Mothers, Narrative, Pandemic, Pregnancy

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted health care delivery and services around the world causing rapid and constant changes to maternity care protocols and pregnant women to give birth with restrictions and significant uncertainties. In this study, mothers' birth stories during the pandemic that were posted to YouTube were analyzed. Rich detailed description of women's lived experience with giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic are presented along with suggestions for nurses to minimize the stress of the vagueness and ambiguity of hospital restrictive practices during the childbirth process in the context of the pandemic.

Figure.

No caption available.

Birth stories during the COVID-19 pandemic can help guide clinical practice to achieve a positive birth experience. Pregnant women with COVID-19 are at an increased risk of severe illness and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth (Woodworth et al., 2020). Elevated stress and anxiety levels have also been reported among pregnant women due to the pandemic (Lebel et al., 2020; Sahin & Kabakci, 2021). Although the pandemic-related stressors (e.g., social isolation, quarantine, face mask, misinformation, and uncertainties) are not unique to this population, changes to hospital and obstetrician policies (e.g., suspension or cancellation of in-person antenatal care and policies restricting visitors during labor and birth) may lead to adverse birth experiences, depression, and poor mental health outcomes (Reingold et al., 2020; Stephens et al., 2020). Researchers speculate that having a negative birth experience, having a sudden change in birth plans, and lacking support during birth are associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (Ayers et al., 2016). During pregnancy, mental health problems are associated with lifelong negative consequences on the mother and fetus (Ayers et al, 2016.). Given these concerns, identifying ways to achieve positive birth experiences as the pandemic evolves is paramount.

Insights from birth stories can lead to a therapeutic relationship between pregnant women and their health care providers, which can guide clinical practice, design care protocols, and facilitate a positive birth experience (Farley & Widman, 2001). As birth stories are individual narratives of the birthing experience, this study is grounded in the underpinnings of the narrative interpretative framework. According to Clandinin and Connolly in Creswell and Poth (2018), “narrative inquiry is stories lived and told” (2000, p. 20) and can be collected as oral or documented collections. Specifically, the narrative analysis explores an individual's lived experiences within the social, familial, linguistic, and institutional context that shapes the experience (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Narratives, also known as storytelling, effectively shape health outcomes and policies across several health domains (Fadlallah et al., 2019).

The constellation of clinical practices and narratives provides intellectual clarity to care practices, offers rich data to understand essential aspects of the childbearing experience, and improves childbearing women and their families' care (Callister, 2004; Charon et al., 2008; Farley & Widman, 2001). In the pandemic context, birth stories may provide a mechanism that can effectively highlight potential problems with COVID-19 maternity care protocols, evaluate existing hospital policies, and examine these policies' unintended consequences. Birth stories can inform clinicians' understanding of women's experiences that may facilitate a positive birth experience.

Birth stories are told through several mediums including social network sites that profoundly affect decision-making across a broad range of health topics, including pregnancy and childbirth (Drozd et al., 2018; Maguire et al., 2015; Morahan-Martin, 2004). Although characteristics of people who use social network sites for health purposes vary significantly across socioeconomic status, research is clear that females use the internet for health information seeking more often than males (Kontos et al., 2014). Pregnant women use different social network platforms for health purposes, such as mobile apps (Carter et al., 2019) and social media (Maguire et al.; Sanders, 2019). Social network platforms such as YouTube offer free video-sharing capabilities that attract millions of viewers and provide a sense of community among users (www.YouTube.com). For these reasons, YouTube has become popular for pregnant women who often share their birth stories (Baraitser, 2017; Longhurst, 2009). We analyzed birth stories shared... data from birth stories shared on YouTube due to YouTube's broad reach, video-sharing capabilities, and accessibility. Analyzing videos on YouTube enables researchers to conduct in-depth qualitative analysis through user-generated birth stories.

Our primary purpose is to provide a detailed description of new mothers' lived experiences during childbirth in the context of COVID-19 and assess what mothers feel nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, and physicians who cared for them could have done differently in response to COVID-19. We used their stories and perspectives to provide answers to the burgeoning questions expectant mothers might have.

Methods

Sample

Data were extracted from YouTube site using the following keywords “coronavirus,” AND “pregnancy,” AND “birth story” on September 9, 2020. We extracted videos posted between January and September 2020. The videos were sorted using the default YouTube algorithm (Sort by—relevance). Additional parameters included (Upload date—year and Type—video).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

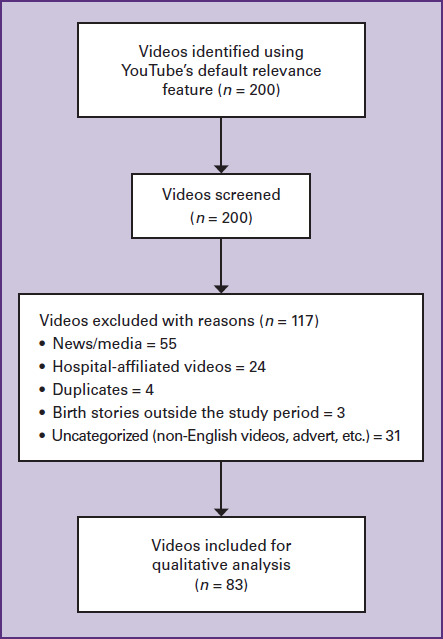

Videos were included in this narrative analysis if they were in English, a first-person account of the birth story, and narrated by women (with or without their partners) who were either pregnant in their second or third trimester or new mothers who gave birth within the study period. We excluded videos from news agencies, hospitals or health-related organizations, health care professionals, duplicate videos in whole or in part, or those from commercial or promotional sources (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

FLOW DIAGRAM OF BIRTH STORIES INCLUDED FOR NARRATIVE ANALYSIS

Data Analysis

Given that internet users seldom go beyond the first pages of any search (Morahan-Martin, 2004), we restricted our initial sample to the first 10 pages or 200 videos (Garg et al., 2015). A literature review of YouTube videos found that of the 37 studies included for review, 30 studies restricted their search to a limited number of pages for analyses (Drozd et al., 2018).

We developed the codebook using an inductive and deductive coding strategy. Specifically, before watching the videos, we educated ourselves with the literature on narrative analysis (Creswell, 2018; Fadlallah et al., 2019), studies reporting birth stories on YouTube and those using other sample populations (Altman et al., 2020; Baraitser, 2017; Callister, 2004; Sanders, 2019), and those reporting obstetric recommendations in the context of the pandemic (Stephens et al., 2020). We coded variables such as when the story was told (pregnancy vs. postpartum), country of the videos, parity, type of delivery, type of birth, and other variables specific to the coronavirus pandemic (e.g., COVID-19-related hospital policies). We established a categorized hypothesis relevant to the literature on pregnant women's experiences during the coronavirus pandemic (Sahin & Kabakci, 2021), such as personal protective equipment (e.g., face masks) by both the patients and health care professionals and use of telehealth services. Two members of the research team iteratively reviewed the generated codes until consensus was achieved. We identified categories such as maternal health conditions and a fill-in field to capture salient points through the inductive process. After watching the videos extensively and in full, we extracted the videos into an Excel sheet where two coders independently and systematically coded 5% of the included videos to establish scientific rigor and interrater reliability by selecting every odd number. The raters agreed on 100% of the extracted videos. Once the codes and code definitions were established, initial coding was done to create category labels. The second stage of coding was done to identify the most relevant categories and subsequently thematize them. One coder coded the remaining videos following the established codebook. This approach allowed for consistency throughout the coding process. We also extracted and recorded video URLs, titles, length, and dates videos were posted.

Ethics

The study was exempted from institutional review board approval because YouTube is a public online database.

Results

We analyzed 83 birth stories. The majority were from the United States (72%), including women in the postpartum period (77%), were singleton births (86%), and vaginal births (63%). Videos ranged from 2 minutes to 1 hour and 2 minutes. See Table 1 for detailed information about video characteristics. Stories followed the narrative analysis constructs (i.e., who, what, where, when) and were mostly told chronologically (data not shown). Narrative analysis revealed four broad themes and 13 subthemes that highlighted different facets of the birthing experiences. Overall, although the mother's experiences were unique, themes reported were consistent across stories analyzed, suggesting that the impacts of the pandemic on birthing mothers are similar across the world.

TABLE 1. CHARACTERISTICS OF BIRTH STORIES FROM YOUTUBE BETWEEN JANUARY AND SEPTEMBER 2020 INCLUDED IN THE ANALYSIS (N = 83).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Country | n (%) |

| United States | 60 (72.2) |

| United Kingdom | 8 (9.63) |

| Canada | 6 (7.22) |

| Australia | 2 (2.4) |

| Spain | 1 (1.2) |

| Jamaica | 1 (1.2) |

| Philippines | 1 (1.2) |

| Switzerland | 1 (1.2) |

| Not reporteda | 3 (2.31) |

| Period Birth Story Was Told | |

| Pregnancy | 4 (4.81) |

| Postpartum period | 67 (80.7) |

| Labor and birth | 12 (14.4) |

| Type of Birth | |

| Vaginal | 55 (66.2) |

| Cesarean | 22 (26.5) |

| Not reporteda | 6 (7.22) |

| Type of Birth | |

| Singleton | 76 (91.5) |

| Twin or triplet | 4 (4.81) |

| Not reporteda | 2 (2.4) |

| Parity | |

| Primiparous | 41 (49.3) |

| Multiparous | 31 (37.3) |

| Not reporteda | 11 (13.2) |

| Birth at Term or Preterm | |

| Full-termb | 72 (86.7) |

| Pretermc | 5 (6.02) |

| Not reporteda | 6 (7.22) |

Videos did not explicitly reveal the information for these categories.

Defined as births >37 weeks.

Defined as births <37 weeks.

Themes

Sense of Loss

An overall sense of loss of the pregnancy and birthing experience under normal conditions (i.e., the ability to have a baby shower or have family present after giving birth) was a common theme conveyed within the videos. The sense of loss made mothers stressed and anxious about their pregnancy experience and their baby's health. As one woman expressed Obviously, being pregnant, one of the things you do is have baby showers. And I had three of them scheduled, and they were all going to be in the month of April. [...]. I remember asking my doctor what she thought about doing these baby showers. And she was like, ‘you're probably not going to be able to do those.’ So, at that point, we had to make the decision to cancel our April baby showers, which was a huge bummer. And being so pregnant and emotional, I was really upset about it. Similarly, the inability to have family members meet the baby after birth also created a sense of loss. Few women experienced a sense of loss because visitors, including spouses and partners, were not allowed during labor or delivery. See Table 2.

TABLE 2. THEMES DESCRIPTIONS AND EXEMPLAR QUOTES.

| Themes and Subthemes | Description | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Themes | ||

| Sense of Loss | Mothers noted they experienced a sense of loss about birthing alone, canceled or changes to their birthing plans, or the fear and worry from the pandemic. |

|

| Hospital Experience | Mothers described their experience with changes to hospital policies in response to the pandemic. |

|

| Experience with Health Care Professionals | Mothers described their experiences with nurses, midwives, and obstetricians. |

|

| Overall Birth Experience Subthemes | ||

| Positive COVID-19 Cases versus Nonpositive COVID-19 Cases | Testing positive for COVID-19 created an unsatisfactory care experience. | We know you have three negatives [COVID tests] back, but we will still treat you like you have it. The nurses were like they didn't want to spend a lot of time in the room, and the lactation nurses declined to come to see me. |

| Hospital Birth vs. Home Birth | Some mothers opted for home birth rather than birthing in the hospital to prevent getting the virus. | This coronavirus is a chaotic time, I had [...] fears. I had to last-minute change my birth plans to help me feel comfortable in giving birth. |

| Bonding with Partner | Hospital policies limiting visitors allowed women to bond with their partner and baby better. |

|

| Having a Healthy Baby | Having a healthy baby diffused the negative feelings of loss from the pandemic. | The main thing was we wanted to have a healthy baby, and all of the things that I missed out on all the craziness that was happening like none of it mattered when it just came down to like the point of all this is for us to just have a baby. All these other things like baby showers and photos and trips like none of that mattered in the midst of just like having a baby. |

| Mentally Prepared | Mental preparation for the worst outcome possible (e.g., birthing alone) allowed women to affirm strength and power over their minds and bodies. | So I was already kind of mentally preparing myself, and I was telling myself like you are strong, you've got this. You giving birth alone is not the end of the world it's not the biggest deal. You are going to be really proud of yourself so I kept telling myself things like that. |

| Faith | Faith in God enhanced coping skills to mitigate stress and worries. | God is just so good because anything could have happened. He works everything out, so I'm just so grateful that He did what He did and everything worked out. |

| Technology | Use of video calling to speak to family members during the birthing process or see their babies that were in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). | What I do like that my hospital did was they FaceTimed me. They had like an iPad there, and they will call me and update me and show me my baby [in the NICU]. |

| Self-Advocating | Need to self-advocate when the care team was not paying attention to needs. | I live 35 minutes away from the hospital, so it's like, why are they sending you home? That doesn't make any sense [...] I kept advocating like hey do you want to keep me [...] even my sister called them to talk to them, and they were like “no.” She also said, “stay home because of COVID-19 or go to the hospital because you know your baby is coming.” |

| Importance of Timely and Effective Communication | Mothers reported poor communication with their health care providers; one titled her story Traumatic Birth Story During Pandemic! | I don't know what to think, you know I'm asking like can someone just let me know what is going on because they're not telling me anything like they're talking amongst themselves, but they're not telling me anything. |

| Postpartum Adjustment | Struggle to adjust to the postpartum period |

|

| Maternal Health Conditions | Women with seemingly healthy pregnancies notified of a potentially threatening health condition. | I was supposed to be here just for an ultrasound, and I'm just here [now going to have an emergency cesarean], and I'm not going home. |

| Child Health Conditions | Mothers who had an adverse birth outcome noted how hospital visiting policies made their birthing experience particularly difficult. |

|

| Limited Knowledge about Childbirth | Limited information about labor and birth | I feel like people go into this black hole of labor and delivery. Two days before I delivered, I was half a centimeter, I've never heard of half a centimeter before. |

Hospital Experience

Due to the pandemic, hospitals modified their check-in process. These modifications made some mothers anxious and concerned about their hospital birthing experience. Most women had to either call in when they reached the hospital or enter through a specific entrance, As soon as we walk from the garage to the door of the hospital, we are greeted with a nurse covered from head to toe in protective gear. They stop us to take our temperature, check our eyes, and tell us to go to the next station. There, we go through a questionnaire and meet a police officer who then gives us wristbands to admit us access to the hospital, and he escorts us to the elevators to triage.

Hospitals also implemented additional specific procedures and protocols to test and screen patients. However, these protocols varied across hospitals and were consistently changing. For example, mothers noted that some obstetricians shared information with them about COVID procedures during their last appointments, but because the situation was constantly changing, there were some inconsistencies. These changes and uncertain hospital policies created a challenge for mothers. See Table 2.

Experience with Health Care Provider

Women in this study revealed that having clear communication and discussing their care options with their provider was soothing. One woman expressed I got to ask all of my questions [...] the nurses came in and introduced themselves...then the anesthesiologist came in and explained everything from start to finish, it brought so much peace of mind having him explain everything and talk me through everything [...], and it made me feel just so much more calm going into it [Cesarean birth].

Mothers and pregnant women talked about being able to discuss their care options with the nurses. They also noted the support they received during labor and birth was instrumental in having a positive birth experience. For example, one mom who was sad because the hospital did not allow a photographer at birth because of the COVID-19 virus reported the nurses helped her take all the pictures during birth, which happened to be the only picture with memories of the birth summed it perfectly. I feel like the nurses and doctors have just gone like above and beyond during this time to make people still feel cared for and feel at ease during this really scary time.

Overall Birth Experience

Thirteen subthemes emerged under the overall birth experience theme. The subthemes including exemplar quotes are listed in Table 2.

Clinical Implications

The “stay at home” orders due to COVID-19 created difficulties for pregnant mothers and family members during pregnancy and birth worldwide. Our study included recently pregnant and postpartum women who described their experiences during pregnancy and birth during the COVID-19 pandemic including changes to birth procedures and interactions with their family and health care providers. They expressed a sense of loss, their interactions with health care providers, unexpected positive experiences, and adverse outcomes during the birth. We found in some cases, mothers had to advocate for care and the maternity team did not provide effective communication during the birth process. Lack of information during pregnancy and birth increases anxiety and fears among first-time moms (Lebel et al., 2020; Sahin & Kabakci, 2021). The right to access information enables women to make informed decisions about their care, which informs respectful care. In the context of the pandemic, upholding clear, effective, and timely communication with women during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period is essential to promoting respectful maternity care, which can improve birth experiences (Altman et al., 2020).

Due to the pandemic, daily routines, social life, leisure activities, and travel restrictions have had an impact on how “soon-to-be” parents interact with their families through social distancing and self-isolation practices (Sahin & Kabakci, 2021). Social isolation and reduced social interaction can result in loneliness, complicating the pregnancy process. It is known that social support is necessary to increase resilience in times of crisis, and poor social support is associated with negative psychological consequences, such as feeling loneliness in pandemics (Brooks et al., 2020). Social support from the pregnant woman's partner, mother, other family members, and peers in the perinatal period is essential in reducing stress, improving coping skills, preventing depression, and adapting to new roles as a mother during pre- and postpartum (McLeish & Redshaw, 2017).

Our findings have important implications for clinicians as our analysis showed that women experiencing pregnancy and childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic faced new challenges, in addition to the usual stressors of being pregnant and becoming a mother. Clinicians, particularly, midwives and nurses are uniquely suited to support women and their families throughout this process. Compassionate, patient-centered communication that provides clear, current information is of paramount importance to allay a woman's anxiety about uncertain and unpredictable policy changes regarding COVID-19 testing and visitor restrictions. Clinicians can foster women's sense of independence and strength by empowering them to participate in decisions about their care and find inner strength through their spiritual beliefs. Hospitals should consider the impact of strict COVID-19 restrictions on mothers who may want to change their birth location but are unable to do so because of their advanced stage of pregnancy. It is important for hospital decision-makers and perinatal providers to consider unintended consequences of the COVID-19 restrictions and policy on birthing experiences and outcomes. This information can be useful in the event of a future public health emergency.

Results shed light on the unique challenges faced by women giving birth in the hospital setting during pandemic restrictions. Through increased awareness of women's birth stories, clinicians in the obstetrics setting can be more responsive to their needs, which may be extraordinary during extraordinary circumstances. Women may be especially vulnerable during postpartum if they lack access to usual social support sources and face isolation. Providers should consider more frequent and earlier contact with new mothers in the days and weeks after giving birth. Screening for depression and anxiety is essential to identify women who need referrals for behavioral health providers' treatment. Postpartum is a period when women's voices should be heard; allowing them the time and space to share their birth stories. Whether as a YouTube video, blog, virtual support group, or more private journal entry, women should be encouraged to share with others about the life-transforming journey to motherhood.

There are some limitations to our study. Using YouTube birth stories provides limited sociodemographic or other background information of the participants that may have helped provide rich insights into our findings. Our sample may not reflect women's viewpoints with low socioeconomic status or from rural areas as studies show a substantial digital divide between high versus low socioeconomic groups (Kontos et al., 2014). We had no way to confirm the veracity of the women's stories, and some of these stories may not have been accurately represented due to their embellishment for entertainment purposes. As with every cross-sectional study, our study only provides a snapshot of the women's lives that may not reflect other variables that may impact their overall birth experiences. Despite these limitations, our study provides important contributions from a global perspective to the limited knowledge of the pandemic's impact on pregnant women and new moms. Results can guide health care providers, policy makers, and researchers on how to incorporate patients' voices to guide a positive birth experience.

SUGGESTED CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Pregnant women reported that the support they received during childbirth was key in providing a positive experience.

Maternity nurses should advocate for mothers by providing emotional support, especially for those birthing alone, to optimize the birthing experience.

Nurses, midwives, and physicians should provide clear and timely information about hospital policies to help mothers make decisions about their birth plans and make them aware that polices may change by the time they give birth.

Health care institutions should adopt technological tools to help mothers stay connected with their infants and support persons, particularly those with adverse birth outcomes

Nurses should endeavor to provide unbiased, respectful, patient-centered care during the pandemic and allow mothers choices whenever possible

INSTRUCTIONS Narrative Analysis of Childbearing Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic

TEST INSTRUCTIONS

Read the article. The test for this nursing continuing professional development (NCPD) activity is to be taken online at www.nursingcenter.com/CE/MCN. Tests can no longer be mailed or faxed.

You'll need to create an account (it's free!) and log in to access My Planner before taking online tests. Your planner will keep track of all your Lippincott Professional Development online NCPD activities for you.

There's only one correct answer for each question. A passing score for this test is 7 correct answers. If you pass, you can print your certificate of earned contact hours and access the answer key. If you fail, you have the option of taking the test again at no additional cost.

For questions, contact Lippincott Professional Development: 1-800-787-8985.

Registration deadline is September 1, 2023.

PROVIDER ACCREDITATION

Lippincott Professional Development will award 2.5 contact hours for this nursing continuing professional development activity.

Lippincott Professional Development is accredited as a provider of nursing continuing professional development by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation.

This activity is also provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP 11749 for 2.5 contact hours. Lippincott Professional Development is also an approved provider of continuing nursing education by the District of Columbia, Georgia, and Florida, CE Broker #50-1223. Your certificate is valid in all states.

Disclosure: The authors and planners have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Payment: The registration fee for this test is $24.95.

References

- Altman M. R., McLemore M. R., Oseguera T., Lyndon A., Franck L. S. (2020). Listening to women: Recommendations from women of color to improve experiences in pregnancy and birth care. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health, 65(4), 466–473. 10.1111/jmwh.13102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S., Bond R., Bertullies S., Wijma K. (2016). The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: A meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychological Medicine, 46(6), 1121–1134. 10.1017/S0033291715002706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraitser L. (2017). YouTube birth and the primal scene. Performance Research, 22(4), 7–17. 10.1080/13528165.2017.1374661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. K., Weston D., Greenberg N. (2020). Psychological impact of infectious disease outbreaks on pregnant women: Rapid evidence review. Public Health, 189, 26–36. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callister L. C. (2004). Making meaning: Women's birth narratives. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 33(4), 508–518. 10.1177/0884217504266898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon R., Wyer P., NEBM Working Group . (2008). Narrative evidence based medicine. Lancet, 371(9609). 296–297. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60156-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Poth C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design (4th Ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Drozd B., Couvillon E., Suarez A. (2018). Medical YouTube videos and methods of evaluation: Literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 4(1), e3. 10.2196/mededu.8527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadlallah R., El-Jardali F., Nomier M., Hemadi N., Arif K., Langlois E. V., Akl E. A. (2019). Using narratives to impact health policy-making: A systematic review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 26. 10.1186/s12961-019-0423-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley C., Widman S. (2001). The value of birth stories. The International Journal of Childbirth Education, 16(3), 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Garg N., Venkatraman A., Pandey A., Kumar N. (2015). YouTube as a source of information on dialysis: A content analysis. Nephrology, 20(5), 315–320. 10.1111/nep.12397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos E., Blake K. D., Chou W. Y. S., Prestin A. (2014). Predictors of ehealth usage: Insights on the digital divide from the health information national trends survey 2012. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(7), e172. 10.2196/jmir.3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C., MacKinnon A., Bagshawe M., Tomfohr-Madsen L., Giesbrecht G. (2020). Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 5–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst R. (2009). YouTube: A new space for birth. Feminist Review, 93(1), 46–63. 10.1057/fr.2009.22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire A., Douglas I., Smeeth L., Thompson M. (2015). Assessment of YouTube videos as a source of information on medication use in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 16(November 2015), 228–228. 10.1002/pds [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J., Redshaw M. (2017). Mothers' accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 28. 10.1186/s12884-017-1220-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morahan-Martin J. M. (2004). How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: A cross-cultural review. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 7(5), 497–510. 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reingold R. B., Barbosa I., Mishori R. (2020). Respectful maternity care in the context of COVID-19: A human rights perspective. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 151(3), 319–321. 10.1002/ijgo.13376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin B. M., Kabakci E. N. (2021). The experiences of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: A qualitative study. Women and Birth, 34(2), 162–169. 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J. (2019). Sharing special birth stories. An explorative study of online childbirth narratives. Women and Birth, 32(6), e560–e566. 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens A. J., Barton J. R., Bentum N. A. A., Blackwell S. C., Sibai B. M. (2020). General guidelines in the management of an obstetrical patient on the Labor and Delivery unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Perinatology, 37(8), 829–836. 10.1055/s-0040-1710308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth K. R., Olsen E. O., Neelam V., Lewis E. L., Galang R. R., Oduyebo T., Aveni K., Yazdy M. M., Harvey E., Longcore N. D., Barton J., Fussman C., Siebman S., Lush M., Patrick P. H., Halai U.-A., Valencia-Prado M., Orkis L., Sowunmi S., ..., Tong V. T. (2020). Birth and Infant Outcomes Following Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pregnancy — SET-NET, 16 Jurisdictions, March 29–October 14, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(44), 1635–1640. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]