Abstract

Introduction:

Respiratory problems are prevalent among persons who work in agriculture, however publications examining the respiratory status in LatinX farmworkers are limited.

The purpose of this study is to assess the respiratory status of LatinX farmworkers across New York State.

Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of data gathered from Spanish language OSHA respiratory questionnaires completed between January 2017 and March 2019. The best of three peak flows were compared with predicted normal values derived from regressions using age, gender, and height.

Results:

Key information was present in 162 Spanish questionnaires. Rates of reported respiratory symptoms were low, less than 2%. 11.7% farmworkers smoked. Best of three peak flows showed a mean of 97.2 ± 16.8 % of predicted.

Discussion:

New York LatinX farmworkers do not appear to have abnormal rates of respiratory symptoms or low peak flows.

Keywords: Occupational lung disease, respiratory diseases, farmworkers

INTRODUCTION

Large segments of American agriculture depend upon the productivity of seasonal and sometimes migratory farmworkers (FW). Of the over 2 million1 such workers in the US, about three-quarters are foreign-born (predominantly in Mexico) and Spanish speaking.2 In the eastern US these Spanish speaking workers are both males (predominantly) and females in their mid-30s with less than eight years of formal education. FW are at risk of a variety of health problems related to their agricultural work. Musculoskeletal injuries related to repetitive motion, heavy lifting and harmful postures;3,4 dermatitis relating to chemical and biologic contacts;5,6 eye injuries7,8 and heat-related injuries9,10 are consistently reported in the medical literature.

In contrast, assessments of the respiratory status of LatinX FW in the United States have been more than limited. Certainly, there are multiple occupational exposures (organic dust, inorganic dust, agrichemicals, allergens, toxic gases, and microorganisms) that put them at risk for respiratory problems. Among reports on the respiratory status of LatinX FW are two useful surveys of FW in California.11,12 One detailed study of Indiana FW specifically examined respiratory complaints and pulmonary function.13 In North Carolina this issue has been repeatedly examined in both FW adults14,15 and children16.

The opportunity to examine this issue presented itself in the setting of medical evaluations for respiratory protection as mandated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).17 In response to recent changes in Environmental Protection Agency regulations, workers exposed to pesticides must be included in an OSHA-compliant respiratory protection program.18 This includes medical clearance for use of a respirator at work and fit testing for an appropriate certified respirator. As a result, increased numbers of farm employers across New York (NY) are seeking respiratory clearance and fit testing for themselves, family members and employees.

Due to considerations of familiarity, convenience and cost, the New York Center Agricultural Medicine and Health (NYCAMH) has been sought for these services by many NY fruit, vegetable, dairy and other farms. The NYCAMH program offers these services in Spanish and provides confidential assistance with the OSHA questionnaires (Spanish or English) for workers with limited literacy. NYCAMH has evaluated Latinx FW for OSHA Respiratory Protection programs on farms from Long Island to western NY.

The purpose of this study is to assess the respiratory status and function of these migrant farmworkers.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of data gathered from all Spanish language OSHA respiratory questionnaires completed at NYCAMH OSHA evaluation between January 2017 and March 2019.

Farm owners self-selected to receive NYCAMH services. NYCAMH services were advertised on the organization’s website and through cooperative extension offices, farm organizations and word of mouth across the state. In many cases farms had previous experience with NYCAMH safety inspection and on-farm training programs. Respiratory screenings/fittings were conducted on farms or at convenient local sites.

Participants completed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Respirator Medical Evaluation Questionnaire.19 As part of OSHA’s Respiratory Protection standard (29 CFR 1910.134), this questionnaire is used as a medical evaluation for all employees before wearing a respirator. This standardized form gathers self-reported height and weight as well as basic demographic information and job details. It explores past medical history, largely focusing upon past cardio-pulmonary problems. The questionnaire probes with detailed questions on pulmonary and cardiovascular symptoms. The pulmonary questions explore resting and exertional shortness of breath; cough and sputum production; wheeze and chest pain. In selected cases workers required assistance to complete either the English or Spanish language version of the questionnaire.

Peak flow measurements were obtained on all participants following instruction in either English or Spanish. The maximum flow achieved during expiration delivered with maximal force starting from full lung inflation was measured with a Mini Wright Peak Flow Meter (Clement Clarke International, Harlow, UK) for three consecutive efforts. Efforts were conducted in the standing position without a nose clip.

Data from all completed Spanish questionnaires were double entered and assessed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Bassett Healthcare Research Institute.20 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.

Questionnaire data was summarized using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables (e.g. job category, history of asthma) and means and standard deviations for continuous variables (e.g. age, years in current job).

The best of the three peak flow efforts was compared with the individual’s predicted normal value and presented as a percent of predicted normal. Each participant’s predicted normal value was derived using published regression equations;21 these equations included the individual’s age, gender, and height.

Each participant’s predicted normal value was derived using published regression equations;21 these equations included the individual’s age, gender, and height. The best of the three peak flow efforts was compared with the individual’s predicted normal value and presented as a percent of predicted normal.

Pearson’s correlation was used to test the association between age and the percent of predicted normal. Mean levels of the percent of predicted normal were compared for presence (defined as a response of “yes” to any question pertaining to a history of lung illness, injury or current symptoms) versus absence of any lung illness or injury using the Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

The Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital IRB approved this study.

RESULTS

All key information was present in 162 Spanish questionnaires. 155 (97.5%) were male. Mean age was 36.1 ± 10.4 years. Most subjects worked on fruit producing operations (46.3%). Dairy (27.2%) and vegetable farms (13.3%) accounted for the majority of other commodities. Nearly three-quarters (72.5%) wore respirators at work. Only 36.2% of farmworkers reported having ever been formally fit tested in the past. Nineteen FW (11.7%) smoked. Additional participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 155 | 97.5 |

| Female | 4 | 2.5 |

| Mean ± SD | Range | |

| Age (years) | 36.1 ± 10.4 | 20–66 |

| Age group | N | % |

| 20–29 | 43 | 28.7 |

| 30–39 | 60 | 40.0 |

| 40–49 | 29 | 19.3 |

| 50–59 | 11 | 7.3 |

| 60+ | 7 | 4.7 |

| Current Smoker | 19 | 11.7 |

| Non-smoker | 143 | 88.3 |

| Mean ± SD | Range | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.3 ± 4.5 | 18.6–42.7 |

| BMI Category | N | % |

| Normal (<25.0 kg/m2) | 35 | 22.7 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 67 | 43.5 |

| Obese (30.0+ kg/m2) | 52 | 33.7 |

| Job Title | ||

| Farm Worker | 138 | 90.8 |

| Farm Owner | 8 | 5.3 |

| Farm Supervisor | 4 | 2.6 |

| Other | 2 | 1.3 |

| Mean ± SD | Range | |

| Years in current job | 9.8 ± 7.7 | 0–39 |

| Farm Type | N | % |

| Dairy | 44 | 27.2 |

| Fruit | 75 | 46.3 |

| Vegetable | 21 | 13.0 |

| Ever worn respirator | 108 | 72.5 |

| Ever been fit-tested | 54 | 36.2 |

Acknowledged past pulmonary problems were rare and are listed on Table 2. Notably, three (1.86%) reported having asthma. Table 3 lists the lung related symptoms that were described by the 162 farmworkers. One (0.62%) has dyspnea at rest, two (1.23%) dyspnea with exertion, and two (1.24%) reported having a productive cough. No FW reported wheezing or chest pain with deep breathing.

Table 2.

Pre-Existing Pulmonary Problems

| “Have you ever had any of the following pulmonary or lung problems” | NO | YES | Percent Positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asbestosis | 160 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Asthma | 158 | 3 | 1.9 |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 160 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Emphysema | 161 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pneumonia | 161 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Tuberculosis | 159 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Silicosis | 161 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pneumothorax | 160 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lung Cancer | 161 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Broken Ribs | 159 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Any chest injuries or surgeries | 159 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Any other lung problem you’ve been told about | 160 | 0 | 0.0 |

Table 3.

Pulmonary Symptoms

| "Do you currently have any of the following symptoms of pulmonary or lung illness" | NO | YES | Percent Positive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortness of breath | 160 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Shortness of breath when walking fast on level ground or walking up a slight hill or incline | 160 | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Shortness of breath when walking with other people at an ordinary pace on level ground | 162 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| centerHave to stop for breath when walking at your own pace on level ground | 161 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Shortness of breath when washing or dressing yourself | 162 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Shortness of breath that interferes with your job | 162 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Coughing that produces phlegm (thick sputum) | 159 | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Coughing that wakes you early in the morning | 160 | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Coughing that occurs mostly when you are lying down | 161 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Coughing up blood in the last month | 162 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Wheezing | 161 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Wheezing that interferes with your job | 161 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Chest pain when you breathe deeply | 162 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Any other symptoms that you think may be related to lung problems | 161 | 0 | 0.0 |

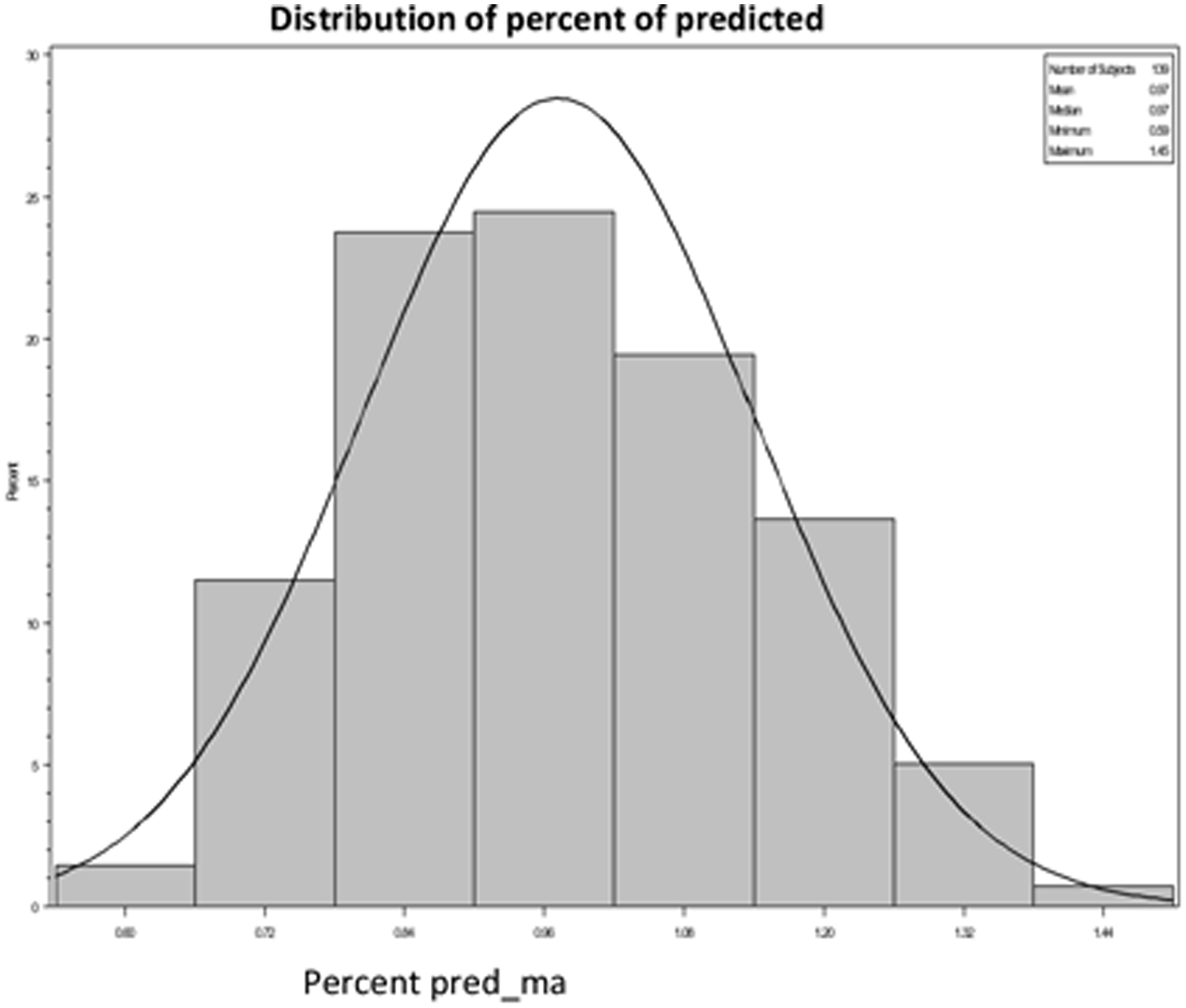

Best of three peak flow showed a mean of 97.2 +/− 16.8% of predicted normal for the group. Predicted normal values were derived from NHANES III data.21 Less than one percent (0.72%) of the peak flow findings were further than 2 standard deviations below predicted normal. 12 (8.6%) of FW had a peak flow value below the lower limit of normal. There were no statistically significant differences between smokers and non-smokers in terms of percent of predicted or by classification of normal values. There was no indication of a correlation between age and the percent of predicted normal (r=0.085, p=0.32). Those that reported lung symptoms, illness or injury did not differ on the percent of predicted from those that reported none of these conditions.

DISCUSSION

Of the limited number of previous assessments of FW respiratory status, several involved workers in California’s Central Valley. In 1992 Gamsky and colleagues reported on a cross-sectional study of 759 grape, tomato and citrus workers.11 Symptoms of chronic cough (1.6%), chronic phlegm (5.1%) and persistent wheeze (2.8%) as well as a current smoking rate of 29% were noted in this group.

In 2015 data from the California community based MICASA Study showed prevalence of 6% for asthma, 5% for chronic cough, 3% for chronic bronchitis, 7% for persistent wheeze and 11.4% for smoking in 702 workers also from the Central Valley of California.12 The majority of these workers were Mexican, and most others were from Central America. Lung symptoms did not correlate with reported exposures to dust or pesticides.

Garcia et al. studied workers living in migrant labor camps of central Indiana in the early 1990’s.13 A total of 354 adult workers, roughly 80% from Mexico, completed questionnaire on demographics, respiratory symptoms and smoking history. This group completed spirometry, with 297 valid spirograms being examined. Rates of chronic wheeze (6.2%), chronic sputum production (6.5%) and chronic cough (8.5%) were relatively high. The proportion of smokers in this group was notably high (43.1%) and symptoms were highly associated with smoking. Over six percent of spirograms showed obstruction (FEV1/FVC <70%) and this correlated with both smoking and years of farm work.

A series of studies on North Carolina workers document somewhat higher rates of respiratory complaints. Using questions derived from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey,22 investigators have studied several groups of LatinX FW. A 2008 study of 122 mostly male workers specifically focused upon wheeze and allergy symptoms across one growing season. These people were mainly employed in tobacco-related activities.14 Twenty-nine (24%) reported ever wheezing and 8% described wheeze within the past month. Seven percent reported waking from cough and 6% were awakened by shortness of breath. Rates were highest among older workers, those with > 8 years farm work and smokers (current + past).

Similar symptoms were assessed in a 2014 study of health relative to housing conditions for farmworkers in North Carolina. These 352 male tobacco workers also performed spirometry. The most common reported respiratory symptoms included: wheeze/whistle (11.4%); awaken with chest tightness (16.8%) or shortness of breath (14%) and productive cough (17.3%). Roughly 30% also mentioned symptoms suggestive of allergic rhinitis /sinusitis. Spirometry was generally normal with abnormal FEV1 being noted in 4.5% of workers. Respiratory symptoms appeared to relate to smoking, use of pesticides in the home, presence of mold and possibly of cockroaches in the bedroom.15

Most recently a 2018 study of 140 LatinX children (11–19 years) working on North Carolina farms described self-reported respiratory symptoms and physician diagnoses and lung function testing.16 This predominantly male (65%) group worked in tobacco, berries, tomatoes and a variety of other commodities. They reported chest tightness/pain in 30.7%; wheeze/whistle in 16.4%; exercise limitation due to cough/wheeze affected 19.3%; and awakening due to respiratory symptoms in 13.6%. Based upon reported symptoms, the authors reported previous or current asthma in 7.9% and “suspected asthma” in 36.4% of these farmworker children. Spirometric evidence of airflow obstruction was noted in 21.4% of subjects.

The present study utilized the questions in the OSHA Respiratory Questionnaire to identify previously diagnosed disease and lung-related symptoms in 162 Spanish-speaking FW. The OSHA list of respiratory symptom questions is comprehensive, and the individual questions are specific and appropriate. However, this list of question has not been rigorously studied for epidemiologic utility, nor has the setting of the OSHA respiratory protection program been utilized before. Workers in the present study described low rates of symptoms - less than 2% for any shortness of breath and for significant cough. None admitted to wheezing. Asthma had been previously identified in 1.9% and chronic bronchitis in 1.2%.

Clearly these rates are less than noted in any of the studies above. These rates are notably below those reported for the agriculture sector (crop, livestock, landscape and horticulture, forestry and fishing).23 This could relate to a number of factors. As noted, the questionnaire may be less sensitive, but the questions are well-formulated, and this seems unlikely. Possibly some aspect of the Spanish language version of the questionnaire affects sensitivity. The pattern of commodities for the NY workers is significantly different than for other studies, particularly the North Carolina studies where tobacco work is prominently featured. Those investigators raised tobacco as a specific factor in several of their analyses. Fruit and dairy accounted for nearly three-quarters of the NY cohort and these have not been involved in most of the previous reports. There might well be a healthy worker-type effect in which employers selectively enroll only some of their workers for the OSHA protection program. However, we suspect that by far the most likely factor in the low rates of reported symptoms is the setting of an employment-based assessment. Some of the NY workers may well have perceived poor performance on the questionnaire as a threat to their continued employment and thus under-reported any respiratory complaints.

Nineteen FW (11.7%) smoked (Figure 1). This compares to a rate of 15.6% in US males and 9.8% among Hispanics in the US.24 A previous 1999 study of North Carolina FW found self-reported smoking within the past seven days in 69 (38.1%) of 181 surveyed workers.25

Figure 1: Peak Flow Findings.

Mean % of Predicted Peak Flow: 97.2 ± 16.8%

Peak flows were a little less than predicted for the NY FW. The mean peak flow for the group was 97.2±16.8% of predicted normal values derived from third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) data (1994) as analyzed by Hankinson.21 These reference values were chosen because they specifically included and assessed normals for Mexican American NHANES III participants. However, it is important to recognize the differences in conditions of the current study versus those under which the predicted peak flow values were derived. NHANES III spirometric testing involved five to eight maneuvers, carefully calibrated spirometers, well-trained technicians and sophisticated real-time quality assessment. The reality of three peak flow efforts by predominantly Spanish-speaking farmworkers during on-farm respirator fit testing stands in stark contrast to the rigorous methodology of NHANES III.

This study shares many of the challenges and weaknesses of other studies of the FW population. There was non-random selection and thus the findings may not be representative of the population of NY FW. There is likely a group of farm owners who simply do not comply with the EPA regulations and thus their workers are not represented at all. Among owners participating there may well be a healthy worker effect further complicating the selection. Employers may have chosen to exclude certain workers from the OSHA Respiratory Protection Program. In a process that is so clearly linked to continued employment, workers might have strong motivation to under-report known health problems and symptoms. Literacy was clearly a challenge for a number of workers. Finally, the OSHA Respiratory Protection Program is not a process designed for collection of epidemiologic data. The OSHA questionnaire provides very reasonable questions for assessment of respiratory status, but the scientific validity of this questionnaire is unknown.

Despite these limitations, the data collected from NY FW during their respiratory protection assessments do provide some insight into the respiratory status of northeastern FW. The demographics of this cohort are similar to many other migrant populations that have been reported. We have found that this group smokes less than the average for the US. Their rates of reported underlying respiratory disease and also of common lung related symptoms are low – remarkably low – relative to almost any other occupational group. In fact, the marked paucity of reported previous disease and current symptoms in our study suggests that OSHA questionnaire-derived respiratory data might best be viewed with skepticism. Peak flows are good, though marginally reduced from predicted normals and much of this reduction might be explained by differences in methodology. As previously reported26, only a minority of this dust and pesticide-exposed population had ever been fit tested for a respirator.

Although much remains to be learned about the lungs of these workers, this study suggests that lung health may be of lower priority than studies and interventions focused upon musculoskeletal, skin, eye and behavioral health issues. The utility of OSHA respiratory responses for these purposes is open to question.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780. Its contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

The authors acknowledge the efforts of Jose Flores in leading the NYCAMH farmworker respiratory protection fit initiative.

Footnotes

Financial and Non-financial disclosures: None to declare.

Contributor Information

Nancy W. Bethuel, Bassett Medical Center, One Atwell Road, Cooperstown NY 13326.

Kai Wasson, New York Center Agricultural Medicine and Health.

Melissa Scribani, Bassett Medical Center, One Atwell Road, Cooperstown NY 13326.

John J. May, Bassett Medical Center, NY Center Agricultural Medicine and Health, One Atwell Road, Cooperstown NY 13326.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcury TA, Mora DC. Latinx farmworkers and farm work in the eastern United States: The context for health, safety, and justice. InLatinx Farmworkers in the Eastern United States 2020. (pp. 11–40). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez T, Gabbard S. Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2015–2016. A Demographic and Employment Profile of United States Farmworkers. Dep Labor Employ Train Adm Wash Dist Columbia. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearney GD, Allen DL, Balanay JA, Barry P. A descriptive study of body pain and work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Latino farmworkers working on sweet potato farms in eastern North Carolina. Journal of agromedicine. 2016July2;21(3):234–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonozzi TR, Layne LA. Hired crop worker injuries on farms in the United States: A comparison of two survey periods from the National Agricultural Workers Survey. American journal of industrial medicine. 2016May;59(5):408–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallejos QM, Schulz MR, Quandt SA, Feldman SR, Galvan L, Verma A, Fleischer AB Jr, Rapp SR, Arcury TA. Self report of skin problems among farmworkers in North Carolina. American journal of industrial medicine. 2008March;51(3):204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham NF, Feldman SR, Vallejos Q, Whalley LE, Brooks T, Cabral G, Earp P, Fleischer AB Jr, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Contact dermatitis in tobacco farmworkers. Contact dermatitis. 2007July;57(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earle‐Richardson G, Wyckoff L, Carrasquillo M, Scribani M, Jenkins P, May J. Evaluation of a community‐based participatory farmworker eye health intervention in the “black dirt” region of New York State. American journal of industrial medicine. 2014September;57(9):1053–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quandt SA, Feldman SR, Vallejos QM, Schulz MR, Verma A, Fleischer AB, Arcury TA. Vision problems, eye care history, and ocular protection among migrant farmworkers. Archives of environmental & occupational health. 2008April1;63(1):13–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischer NL, Tiesman HM, Sumitani J, Mize T, Amarnath KK, Bayakly AR, Murphy MW. Public health impact of heat-related illness among migrant farmworkers. American journal of preventive medicine. 2013March1;44(3):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirabelli MC, Quandt SA, Crain R, Grzywacz JG, Robinson EN, Vallejos QM, Arcury TA. Symptoms of heat illness among Latino farm workers in North Carolina. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010November1;39(5):468–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamsky TE, Schenker MB, McCurdy SA, Samuels SJ. Smoking, respiratory symptoms, and pulmonary function among a population of Hispanic farmworkers. Chest. 1992May1;101(5):1361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoecklin-Marois MT, Bigham CW, Bennett D, Tancredi DJ, Schenker MB. Occupational exposures and migration factors associated with respiratory health in California Latino farm workers: the MICASA study. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine. 2015February1;57(2):152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia JG, Matheny Dresser KS, Zerr AD. Respiratory health of Hispanic migrant farm workers in Indiana. American journal of industrial medicine. 1996January;29(1):23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirabelli MC, Hoppin JA, Chatterjee AB, Isom S, Chen H, Grzywacz JG, Howard TD, Quandt SA, Vallejos QM, Arcury TA. Job activities and respiratory symptoms among farmworkers in North Carolina. Archives of environmental & occupational health. 2011July1;66(3):178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kearney GD, Chatterjee AB, Talton J, Chen H, Quandt SA, Summers P, Arcury TA. The association of respiratory symptoms and indoor housing conditions among migrant farmworkers in eastern North Carolina. Journal of agromedicine. 2014October2;19(4):395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearney GD, Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Talton JW, Arnold TJ, Sandberg JC, Wiggins MF, Daniel SS. Respiratory Health and Suspected Asthma among Hired Latinx Child Farmworkers in Rural North Carolina. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020October29;17(21):7939. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Standard number / 1910.134 – Respiratory Protection. Accessed at: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardsnumber/1910/1910.134.February26, 2021

- 18.US Environmental Protection Agency. Pesticide Worker Safety. 2015accessed at: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-worker-safety/regulatory-information-2015-agricultural-worker-protection-standard-wps June 7, 2020

- 19.US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Standard number / 1910.134 App C – OSHA Respirator Medical Evaluation Questionnaire (Mandatory). Accessed at:. February26, 2021https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardsnumber/1910/1910.134AppC

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009April1;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general US population. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999January1;159(1):179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burney PG, Luczynska C, Chinn S, Jarvis D. The European community respiratory health survey. European respiratory journal. 1994May1;7(5):954–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greskevitch M, Kullman G, Bang KM, Mazurek JM. Respiratory disease in agricultural workers: mortality and morbidity statistics. J Agromedicine. 2007;12(3):5–10. doi: 10.1080/10599240701881482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. 2020accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htmJune19, 2020

- 25.Spangler JG, Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Preisser JS. Tobacco use among Mexican farmworkers working in tobacco: implications for agromedicine. Journal of agromedicine. 2003January1;9(1):83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Earle-Richardson G, Fiske T, Wyckoff S, Shuford J, May J. Respiratory fit testing for farmworkers in the Black Dirt region of Hudson Valley, New York Journal of agromedicine. 2014October2;19(4):346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]