Abstract

Background:

Surgical stabilization of rib fractures (SSRF) has become increasingly common for the treatment of traumatic rib fractures; however, little is known about related postoperative readmissions. The aims of this study were to determine the rate, and cost of readmissions as well as to identify patient, hospital, and injury characteristics that are associated with risk of readmission in patients who underwent SSRF. The null hypotheses were that readmissions following rib fixation were rare and unrelated to the SSRF complications.

Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of the 2015–2017 Nationwide Readmission Database. Adult patients with rib fractures treated by SSRF were included. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to compare patients readmitted within 30 days to those who were not, based on demographics, comorbidities, and hospital characteristics. Financial information examined included average visit costs and national extrapolations.

Results:

2,522 patients who underwent SSRF were included, of whom 276 (10.9%) were readmitted within 30 days. In 36.2% of patients the reasons for readmissions were related to complications of rib fractures or SSRF. The rest of the patients (63.8%) were readmitted due to mostly non-trauma reasons (32.2%) and new traumatic injuries (21.1%) among other reasons. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that ventilator use, discharge other than home, smaller hospital size, and medical comorbidities were significantly associated with risk of readmission. Nationally, an estimated 2,498 patients undergo SSRF each year, with costs of $176 million for initial admissions and $5.9 million for readmissions.

Conclusions:

Readmissions after SSRF are rare and mostly attributed to the reasons not directly related to sequelae of rib fractures or SSRF complications. Interventions aimed at optimizing patients’ pre-existing medical conditions prior to discharge should be further investigated as a potential way to decrease rates of readmission after SSRF.

Level of Evidence:

Epidemiological study, level III

Keywords: Surgical stabilization, rib fracture, readmission, cost

BACKGROUND

Hospital readmissions rates are under intense scrutiny as an indicator of quality. Readmission statistics are publicly reported for selected conditions and factor into payment adjustments in the accountable care organization model (1). In addition to the potential for decreased reimbursement, readmissions also induce high direct financial stress, with an estimated $17.4 billion in costs within the Medicare population alone (2). Despite this focus, readmission rates remain high; almost 20% of all hospital visits result in a second admission within 30 days, with roughly 90% of these being unplanned (1,2). Of these, around 27% can be considered avoidable, although estimates vary widely (3).

Rib fracture is a common occurrence with up to 10% of all trauma patients having a fracture of one or more ribs (4). Historically, patients with rib fractures were managed nonoperatively with aggressive pain management, pulmonary toilet, and selective mechanical ventilation. There has been a growing body of evidence supporting the benefits of SSRF over nonoperative management, including shorter duration of mechanical ventilation, shorter length of stay in both the ICU and hospital, lower incidence of pneumonia and need for tracheostomy, and decreased overall mortality (4).

Despite the clinical benefits, its acceptance in certain patterns of rib fractures remains controversial and little is known about readmissions following operative rib fixation, with no large studies to date (5,6,7). Not only is the incidence of readmission and its resulting cost unknown in this population, but information is lacking on the type of patients, injury characteristics and specific hospitals that may influence this outcome.

The aims of this study were to determine the rate, and cost of readmissions as well as to identify patient, hospital, and injury characteristics that are associated with risk of readmission in patients who underwent SSRF. The null hypotheses were that readmissions following rib fixation were rare and unrelated to the SSRF complications. The primary outcome was the overall rate of readmissions.

Methods

Data Source

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval at our institution, data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) between October 2015 to December 2017 was reviewed. Data prior to October 2015 was not used to prevent data inconsistency due to the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding. The NRD is a collation of the State Inpatient Databases sponsored by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). It reports admissions from 27 states, accounting for 56.6% of all national hospitalizations. This is a de-identified, administrative, non-clinical database. Access to the NRD is open, but not free, to those who have completed the NRD data-use agreement and training.

All patients 15 years of age or older with rib fracture and who underwent SSRF were included in this study. The patients were then divided into one of two study arms: those who were readmitted within 30 days of discharge and those who were not readmitted within 30 days of discharge. The analysis of readmissions only considered index admissions for October to November for the 2015 database and January to November for the 2016–2017 databases. The exclusion of index admissions from December of each sample ensured that each patient was given an equivalent time-opportunity for a 30-day readmission to occur, as patient identifiers are only linked within an individual calendar year.

Rib fractures were defined as ICD-10 Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes S2231XA, S2231XB, S2232XA, S2232XB, S2239XA, S2239XB, S2241XA, S2241XB, S2242XA, S2242XB, S2243XA, S2243XB, S2249XA, S2249XB, S225XXA, S225XXB. Rib fixation was defined by ICD-10 Procedure (ICD-10 PCS) codes 0PH104Z, 0PH134Z, 0PH144Z, 0PH204Z, 0PH234Z, 0PH244Z, 0PS104Z, 0PS134Z, 0PS144Z, 0PS204Z, 0PS234Z, 0PS244Z.

Variables

Demographic and socioeconomic variables in this study included age, sex, income quartile for the patient’s home zip-code, and urban-vs-rural home zip-code. Comorbid conditions were examined using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI). These comorbid conditions were examined as both individual clinical conditions and as ECI summary scores for risk of readmission and mortality. Summary scores were generated using HCUP provided coding, which assigns a numeric score to each comorbidity present based on predetermined relative risk.

Characteristics of the inpatient stay examined were length of stay (LOS), total charges, and discharge disposition after the index admission. For multivariate analyses, the “Discharge other than home” variable included all discharge dispositions except routine (home without additional services), home health (home with additional services), and against medical advice (AMA). Rib fractures were classified as open or closed. Closed fractures were defined as ICD-10 CM codes S22.31XA, S22.32XA, S22.39XA, S22.41XA, S22.42XA, S22.43XA, S22.49XA, S22.5XXA, while open fractures were defined as ICD-10 CM codes S22.31XB, S22.32XB, S22.39XB, S22.41XB, S22.42XB, S22.43XB, S22.49XB, S22.5XXB. Flail chest was defined as ICD-10 CM codes S22.5XXA and S22.5XXB. Underlying lung injury, including contusion, laceration, and unspecified injury, was defined as ICD-10 CM codes S27.3.

All-Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Group (APR-DRG) codes were also examined. These variables are pre-computed by the NRD and assign an overall severity-of-illness score and risk-of-mortality to each patient. These scores are created by categorizing each admission diagnosis, stratifying by severity or risk, and modifying the risk score based on secondary diagnoses. Scores for individual diagnoses are merged to create the overall risk-of-mortality and severity scores for each patient.

Three hospital level variables were examined: hospital size, private versus public ownership, and a variable that differentiated rural, urban-academic, and urban-non-academic institutions.

Outcomes

Readmission is not a defined variable within the NRD. Rather, each admission is coded with a visit identifier and a patient identifier. The latter can be used to track multiple admissions by one patient. For this study, the index admission was defined as the first admission in which a diagnosis of rib fracture with SSRF was noted. The first subsequent visit within 30 days was defined as a readmission. Visits beyond these 30 days were not counted as either new index admissions or readmissions.

Reasons for readmission were defined as the primary ICD-10 CM code during the return visit. The authors performed a review of these codes to create clinically relevant composite reasons for readmission divided into two groups. One group contained all diagnoses that could be potentially directly attributed to the fracture of a rib or subsequent SSRF. The second group had diagnoses that could not be attributed to SSRF or rib fractures. Categorizations were determined using multi-author review; two authors (NB and BJ) independently reviewed all diagnosis codes, then discussed and resolved any discrepancies with a third author present (JA). The clinical judgement and experience of the authors was used as the NRD does not contain enough information to determine a causal connection between any two diagnoses. If a readmission diagnosis could be attributable to other injuries or procedures as well as SSRF, (such a cellulitis, post-trauma pain), it was still classified as attributable to SSRF in order to analyze readmissions as a worst-case scenario. (See Appendix 1: Readmission coding table).

Financial information in the NRD is reported as charges, the amount billed to a patient. Costs to the hospital itself can be estimated by multiplying these charges by cost-to-charge ratios. The NRD contains cost-to-charge ratios for each hospital based on CMS Healthcare Cost Reporting Information System data and has internally validated this method (8). Both actual charges and cost estimates of each admission were examined in this study.

NRD data can be used to produce nationwide estimates of the number of admissions and costs. This is done by using NRD defined weights for each hospital that are based on institutional characteristics such as size, urban versus rural location, teaching status, and hospital ownership. These weights were used when creating national estimates of cost and overall admission numbers, but not during the statistical analysis of readmission predictors as the later section of the analysis was focused on relationships between variables, not overall readmission trends.

This study excluded 12 months of index admissions from the 3 years available. Three of those months were excluded for being the last month of each data set, and the remaining 9 were excluded for using ICD-9 coding. Therefore, to generate national estimates over the course of 3 years, estimates were multiplied by a factor of 36/24.

Statistical Analysis:

Univariate associations between patient or hospital characteristics and readmission were determined using the Mann-Whitney-U test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Post-hoc chi-square testing for categorical variables was conducted using the Bonferroni correction for multiple analyses. A hierarchical logistic regression was used to determine the significance of variables in a multivariate setting while controlling for the hospital-level variables. Variables for multivariate analysis were chosen based on results of univariate analysis and clinical relevance. A formal power analysis was not performed, however the analysis adhered to the guideline of >10 events per predictor in the multivariate setting.

The alpha level was set at 0.05 for all tests. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

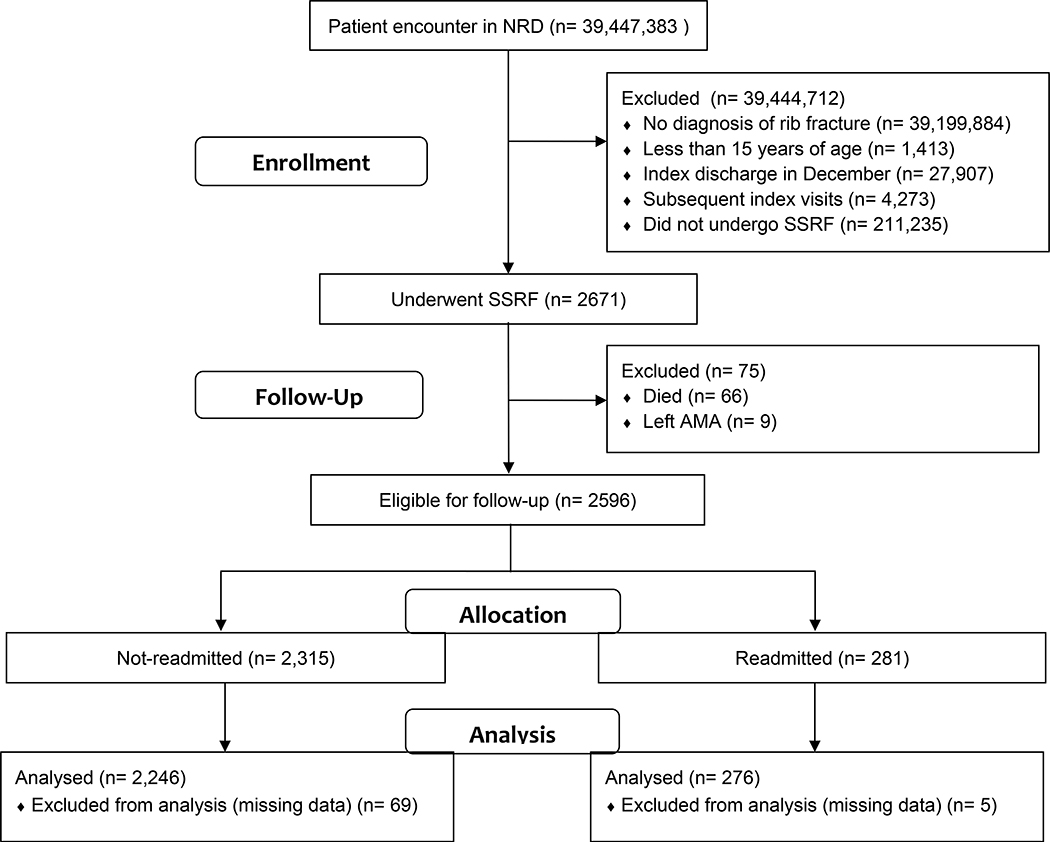

Between October 1st 2015 and December 31st 2017, 39,447,383 patients were followed in the NRD. Of these, 2,522 underwent SSRF and were included for analysis. 276 (10.9%) of the patients who underwent SSRF were readmitted. Figure 1 details the number of patients included/excluded at each phase of analysis.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for inclusions/exclusions for this study. P-value for missing data between the two arms is 0.2532.

Univariate Comparison of Readmitted and Non-Readmitted Patients

Higher ECI scores were significantly associated with readmission, as was increasing patient age, and primary payer, with readmitted patients being more likely to use Medicare as opposed to Private insurance or self-pay. Neither sex nor zip-code income quartile were significantly related to readmission. Comparisons of patient demographics and specific comorbidities between the readmitted and non-readmitted groups can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient characteristics at the time of the index admission between those ultimately readmitted and those who were not readmitted.

| All (n = 2,522) | Non-readmitted (n = 2,246) | Readmitted (n = 276) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Age (Median, IQR) | 57 (47–67) | 57 (47–67) | 60 (51–70) | 0.0003 |

| Female | 643 (25.5%) | 572 (25.5%) | 71 (25.7%) | 0.9263 |

| Zip Code Income Quartile | 0.6950 | |||

| 1 (Lowest) | 647 (25.7%) | 575 (25.6%) | 72 (26.1%) | |

| 2 | 665 (26.4%) | 600 (26.7%) | 65 (23.6%) | |

| 3 | 680 (27.0%) | 600 (26.7%) | 80 (29.0%) | |

| 4 (Highest) | 530 (21.0%) | 471 (21.0%) | 59 (21.4%) | |

| Payer | 0.0029 | |||

| Medicaid | 305 (12.1%) | 272 (12.1%) | 33 (12.0%) | |

| Medicare | 712 (28.2%) | 610 (27.2%) | 102 (37.0%) | |

| Private | 1052 (21.7%) | 946 (42.1%) | 106 (38.4%) | |

| Self/Other | 453 (18.0%) | 418 (18.6%) | 35 (12.7%) | |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | ||||

| Readmission Score (Median, IQR) | 9 (0–21) | 8 (0–20) | 14 (6–26) | <0.0001 |

| Mortality Score (Median, IQR) | 2 (−1–11) | 2 (−1–11) | 4 (0–13) | 0.0098 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions | ||||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 341 (13.5%) | 307 (13.7%) | 34 (12.3%) | 0.5360 |

| Anemia (chronic blood loss) | 251 (10.0%) | 211 (9.4%) | 40 (14.5%) | 0.0076 |

| Blood loss | 39 (1.6%) | 33 (1.5%) | 6 (2.2%) | 0.3706 |

| CHF | 112 (4.4%) | 89 (4.0%) | 23 (8.3%) | 0.0009 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 408 (16.2%) | 353 (15.7%) | 55 (19.9%) | 0.0731 |

| Coagulopathy | 182 (7.2%) | 157 (7.0%) | 25 (9.1%) | 0.2103 |

| Depression | 266 (10.6%) | 225 (10.0%) | 41 (14.9%) | 0.0135 |

| Diabetes Mellitus without complications | 207 (8.2%) | 180 (8.0%) | 27 (9.8%) | 0.2126 |

| Diabetes with Chronic Complications | 206 (8.2%) | 176 (7.8%) | 30 (10.9%) | 0.0825 |

| Drug Abuse | 129 (5.1%) | 117 (5.2%) | 12 (4.4%) | 0.5399 |

| HTN | 1098 (43.5%) | 962 (42.8%) | 136 (49.3%) | 0.0416 |

| Hypothyroidism | 159 (6.3%) | 125 (6.0%) | 24 (8.7%) | 0.0833 |

| Liver Disease | 92 (3.7%) | 82 (3.7%) | 10 (3.6%) | 0.9815 |

| Lymphoma | 5 (0.2%) | 4 (0.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.4401 |

| Electrolyte Disorder | 959 (38.0%) | 837 (37.3%) | 122 (44.2%) | 0.0251 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 15 (0.6%) | 14 (0.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1.0000 |

| Neurological Disorder | 196 (7.8%) | 168 (7.5%) | 28 (10.1%) | 0.1186 |

| Obesity | 303 (12.0%) | 264 (11.8%) | 39 (14.1%) | 0.2519 |

| Paralysis | 59 (2.3%) | 26 (2.1%) | 13 (4.7%) | 0.0058 |

| PVD | 105 (4.2%) | 90 (4.0%) | 15 (5.4%) | 0.2625 |

| Psychoses | 72 (2.9%) | 60 (2.7%) | 12 (4.4%) | 0.1145 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorder | 48 (1.9%) | 41 (1.8%) | 7 (2.5%) | 0.4148 |

| Renal Failure | 118 (4.7%) | 98 (4.4%) | 20 (7.3%) | 0.0323 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 45 (1.8%) | 40 (1.8%) | 5 (1.8%) | 1.0000 |

| Tumor | 35 (1.4%) | 31 (1.4%) | 4(1.5%) | 0.7889 |

| Ulcer | 16 (0.6%) | 11 (0.5%) | 5 (1.8%) | 0.0239 |

| Valvular Disease | 61 (2.5%) | 50 (2.2%) | 11 (4.0%) | 0.0726 |

| Weight Loss | 257 (10.2%) | 219 (9.8%) | 38 (13.8%) | 0.0373 |

IQR, interquartile range; CHF congestive heart failure; HTN, arterial hypertension; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Characteristics of each injury, including whether the rib fracture was open or not, presence of flail chest, and underlying lung trauma, were not associated with risk of readmission. A Minor or Extreme Loss of Function APR-DRG severity score was significantly associated with readmissions. However, risk of mortality based on APR-DRG coding was not. The additional analyses showed that during the initial admission 92.5% of all SSRF patients with the Extreme Loss of Function APR-DRG severity score also had the APR-DRG Extreme Likelihood of Mortality. During the initial stay, those who required mechanical ventilation and a discharge disposition other than home, were significantly more likely to be readmitted (Table 2). An increased hospital size was associated with a lower risk of readmission. Otherwise, there were no significant differences in hospital characteristics, including ownership, teaching status, and rural or urban location between readmitted and non-readmitted patients (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics at the time of the index admission between those ultimately readmitted and those who were not readmitted.

| All (n = 2,522) | Non-readmitted(n = 2,246) | Readmitted(n = 276) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injury Characteristics | ||||

| Open Fracture | 19 (0.8%) | 19 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.2559 |

| Number of Ribs Fractured | 0.1483 | |||

| Single | 85 (3.4%) | 71 (3.2%) | 14 (5.1%) | |

| Multiple | 1303 (51.7%) | 1155 (51.4%) | 148 (53.6%) | |

| Flail Chest | 1134 (45.0%) | 1020 (45.4%) | 114 (41.3%) | |

| Underlying Lung Trauma | 1192 (27.3%) | 1065 (47.4%) | 127 (46.0%) | 0.6595 |

| APR-DRG Summary Statistics | ||||

| Risk of Mortality | 0.0680 | |||

| Minor Likelihood | 544 (21.6%) | 482 (21.5%) | 62 (22.5%) | |

| Moderate Likelihood | 620 (24.6%) | 563 (25.1%) | 57 (20.7%) | |

| Major Likelihood | 754 (29.9%) | 679 (30.2%) | 75 (27.2%) | |

| Extreme Likelihood | 604 (24.0%) | 522 (23.2%) | 82 (29.7%) | |

| Severity | 0.0260 | |||

| Minor Loss of Function | 93 (3.7%) | 76 (3.4%) | 17 (6.2%) | |

| Moderate Loss of Function | 515 (20.4%) | 461 (20.5%) | 54 (19.6%) | |

| Major Loss of Function | 929 (36.8%) | 843 (37.5%) | 86 (31.2%) | |

| Extreme Loss of Function | 985 (39.1%) | 866 (38.6%) | 119 (43.1%) | |

| Stay Characteristics (Initial Admission) | ||||

| LOS (Median, IQR) | 12 (7–19) | 12 (7–19) | 12 (7–23) | 0.5401 |

| Ventilator Use, n(%) | 58 (2.3%) | 43 (1.9%) | 15 (5.4%) | 0.0002 |

| Total Charges (in 1,000's) (Median, IQR) | 213 (120–382) | 212 (122–374) | 220 (94–424) | 0.4177 |

| Discharge Disposition | <0.0001 | |||

| Routine | 1216 (52.2%) | 1210 (53.9%) | 106 (38.4%) | |

| Short Term Hospital | 39 (1.6%) | 30 (1.3%) | 9 (3.3%) | |

| SNF/ICF/Other | 731 (29.0%) | 622 (27.7%) | 109 (39.5%) | |

| Home Health | 436 (17.3%) | 284 (17.1%) | 52 (18.8%) | |

| Year of Discharge | 0.1921 | |||

| 2015 | 130 (5.2%) | 113 (5.0%) | 17 (6.2%) | |

| 2016 | 1004 (39.8%) | 883 (39.3%) | 121 (43.8%) | |

| 2017 | 1388 (55.0%) | 1250 (55.7%) | 138 (50.0%) |

IQR, interquartile range; SNF, skilled nursing facility; ICF, intermediate care facility; APR-DRG, All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups; LOS, length of stay.

Table 3.

Comparison of hospital characteristics at the time of the index admission between those ultimately readmitted and those who were not readmitted.

| All (n = 2,522) | Non-readmitted (n = 2,246) | Readmitted (n = 276) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||

| Hospital Ownership | 0.3676 | |||

| Nonfederal Government | 342 (13.6%) | 310 (13.8%) | 32 (11.6%) | |

| Private, Non-Profit | 1763 (69.9%) | 1650 (69.5%) | 203 (73.6%) | |

| Private, For Profit | 416 (16.5%) | 376 (16.7%) | 41 (14.9%) | |

| Hospital Size | 0.0023 | |||

| Small | 144 (5.7%) | 116 (5.2%) | 28 (10.1%) | |

| Medium | 677 (26.8%) | 600 (26.7%) | 77 (27.9%) | |

| Large | 1701 (67.5%) | 1530 (68.1%) | 171 (62.0%) | |

| Hospital Teaching/Rural | 0.0901 | |||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 431 (17.1%) | 383 (17.1%) | 48 (17.4%) | |

| Metropolitan teaching | 2036 (80.7%) | 1814 (80.8%) | 222 (80.4%) | |

| Non-metropolitan | 55 (2.2%) | 49 (2.2%) | 6 (2.2%) | |

| Hospital Rurality | 0.7855 | |||

| Large Metropolitan | 1290 (51.2%) | 1145 (51.0%) | 145 (52.5%) | |

| Small Metropolitan | 1177 (46.7%) | 1052 (46.8%) | 125 (45.3%) | |

| Micropolitan | 49 (1.9%) | 43 (1.9%) | 6 (2.2%) | |

| Non-urban Residual | 6 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) |

Reasons for readmissions

Most readmissions (63.8%) had the first listed diagnosis not directly attributable to SSRF or rib fractures; this includes unrelated non-trauma reasons in 32.2% of patients. Readmissions that appeared to be related to the initial injury were most commonly due to surgical wound infections (10.1%), followed by pleural effusions (4.3%), pneumonia (4.3%), and other pulmonary complications (3.6%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Primary diagnosis during the readmission visit.

| Diagnosis | |

|---|---|

| SSRF or rib fractures related diagnoses, total | 100 (36.2%) |

| Surgical infectious complications | 28 (10.1%) |

| Sepsis, septicemia | 26 (9.4%) |

| Pleural effusion | 12 (4.3%) |

| Pneumonia, COPD exacerbation, other respiratory complications | 12 (4.3%) |

| Other pulmonary complications | 10 (3.6%) |

| Pneumothorax | 4 (1.4%) |

| Post trauma pain, care | 2 (0.7%) |

| Subsequent encounter for rib fracture | 2 (0.7%) |

| Hemothorax | 2 (0.7%) |

| Surgical non-infectious complications | 2 (0.7%) |

| Not related to SSRF or rib fractures diagnoses, total | 176 (63.8%) |

| Non-trauma reasons | 89 (32.2%) |

| New Injury | 61 (21.1%) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 13 (4.7%) |

| Non-thoracic trauma, subsequent encounter | 13 (4.7%) |

Denominator for all diagnoses is a total number of readmitted patients, 276.

Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Readmission

The multivariate analysis demonstrated that pre-existing conditions, ventilator use, small hospital size and discharge to a location other than home predicted 30-days readmissions (Table 5). The model also showed that those who had APR-DRG Minor Loss Function, had a higher risk of readmissions (Extreme Loss of Function serving as a reference).

Table 5.

Logistic model to determine characteristics associated with readmission risk.

| Covariate | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| APR-DRG Severity | 0.0083 | |

| Minor Loss of Function | 2.42 (1.33–4.39) | |

| Moderate Loss of Function | 1.23 (0.84–1.8) | |

| Major Loss of Function | 0.9 (0.65–1.23) | |

| Extreme Loss of Function | REF | |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.0003 |

| Discharge other than home | 1.62 (1.2–2.19) | 0.0016 |

| Hospital Size | 0.0043 | |

| Small | REF | |

| Medium | 0.55 (0.33–0.9) | |

| Large | 0.46 (0.29–0.74) | |

| Ventilator use | 2.37 (1.25–4.49) | 0.0080 |

REF, reference group; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Costs and Projected Readmissions

Initial SSRF visits had median charges to patients of $213,322 (IQR $119,827-$382,445) with a median hospital cost of $50,936 (IQR: $32,545–86581). Of the readmitted patients in our sample, median charges to patients accumulated during the readmission were $51,740 (IQR: 28,226–104,917) with median hospital costs of $14,355 (IQR: $7,639-$26,960) per patient. Averaging the total cost of readmission over all patients treated with SSRF, the readmission cost per treated patient is $2,349.

Using the NRD weighting system and correcting for the exclusion of the last months of index admissions, it can be estimated that nationally, 2,498 patients would meet our inclusion criteria per year, of whom 273 (10.9%) would be readmitted. Using these estimates, annual charges of the index admission would total $737 million with hospital costs of $176 million. Readmissions following SSRF would have annual charges of $22.8 million with actual hospital cost of readmissions totaling $5.9 million.

DISCUSSION

This is the largest existing study evaluating hospital readmission following SSRF. This study demonstrated that patients with rib fractures treated by operative fixation had a low rate of readmission. Most readmissions were unrelated to SSRF or short-term rib fractures related complications. Among patients who were readmitted, the most common SSRF-related complication was surgical infection. Overall, the costs associated with readmission are low.

Despite the growing popularity of SSRF among surgeons, with rates increasing from 1% prior to 2010 to 10% after 2010 (7), readmission of patients after SSRF has only been reported in two studies. In a single-institution retrospective analysis, Fitzgerald et al (9) looked at surgical stabilization of rib fractures in patients over 65 years of age and noted a 0% readmission rate in the 23 patients undergoing SSRF. Dehgan et al (7) examined the role of SSRF in the management of flail chest through the Ontario health insurance data from 2018 and found a 28.6% 30-day readmission rate among the 77 patients undergoing SSRF. At one year, the readmission rate had increased to 42.9% in this group. The reasons for readmission were not explored in either of these studies. In contrast, our study has a larger cohort and was specifically designed to evaluate readmission rates and the reason for readmission after SSRF. The use of a database that contains over half of all national admissions allows us to define a readmission rate with much more certainty than other studies and examine numerous risk factors simultaneously. This information can be used by surgical and quality improvement teams seeking to lower readmission rates, and to provide a more accurate estimation of risks when consenting patients to surgery.

The reported 30-day readmission rates for all trauma patients are variable among the published data, and no large studies have been specifically designed to examine readmission rates in trauma patients undergoing SSRF. We found a 10.9% readmission rate at 30-days in patients undergoing SSRF. The rate of SSRF readmission in our study is comparable to the national average rate of readmission following any traumatic injury, as reported by two large NRD-based studies and few single institutional reviews examining 30-day readmissions with documented rates between 4.3% and 10.3% (10–13).

The reasons for readmission after SSRF, which had not been previously investigated, were evaluated as well. All first listed diagnoses at time of readmission were grouped based on clinical relevance into two groups: SSRF/rib fracture-related, and non-SSRF/rib fracture-related. Readmissions in our patients were most commonly (63.8%) unrelated to rib fracture or fixation. The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was utilized to reflect the total comorbidity burden in our population, which provides an estimate of the risk of either mortality or readmission based on the presence of comorbid conditions. A higher ECI score in both the mortality and readmission domain, as demonstrated in our patient population, was significantly associated with a higher risk of readmission. These findings are in line with previously published studies that reported higher readmission rates in those with preexisting medical conditions (10–13). In contrast, Parecco et al (14) found that infectious complications including sepsis/septicemia were associated with a higher readmission rate. The difference between our results likely attributed to defining primary readmission cause based on APR-DRG classification by Parecco et al as opposed to ICD-10 coding in our study. We believe the clinical-based nature of the ICD-10 coding system is more reliable than APR-DRG for the purposes of our investigation. Therefore, we believe that attempts to lower readmission rates after SSRF should center around the optimization of patients preexisting conditions by a medical service prior to discharge. Developing a protocol for optimization prior to discharge could potentially decrease future rates of readmission, however further investigation is needed in this area.

Within the small number of patients that required readmission, several predictors of readmission, aside from comorbid conditions, emerged. We found that patients were more likely to be readmitted if they required ventilator use, were treated at a smaller hospital, were discharged somewhere other than home. Among others, the APR-DRG severity score indicating Minor Loss of Function, was found to be an additional predictor of readmissions as compared to Extreme Loss of Function. This was a surprising finding. First, the predictive model was evaluated by an independent consultant. Once the predictive model was verified, the authors discussed the potential explanations for this finding, one of which was the following. Since 92.5% of all SSRF patients with the Extreme Loss of Function APR-DRG severity score also had the Extreme Likelihood of Mortality APR-DRG score, once discharged, those patients had a high risk of death during the 30-days post-discharge period, which could decrease the number of these types of patients being readmitted. On the other hand, none of SSRF patients with the Minor Loss of Function APR-DRG severity score had the Extreme Likelihood of Mortality APR-DRG score and were more likely to survive 30-days period and had a risk of being readmitted. Unfortunately, NRD does not provide the data to verify this explanation.

Surgical infectious complications were by far the most common SSRF/rib-fracture related reason requiring readmission, followed by pleural effusions, pneumonia, and other pulmonary complications. No non-infectious rib-fixation hardware complications were noted as primary reasons for readmission. The complications associated with SSRF have been described in several publications, but their contribution to readmission rate have not been investigated. In a multinational study, hardware failure occurred in 3% of cases (19). Another single center study found that 3.5% of SSRF patients developed hardware infection, with increased body mass index, LOS, and hemorrhagic shock positively associated with infection (20). Thiels (21) specifically examined hardware infections after SSRF, reporting a rate of 4.1%, but did not cite data regarding need for readmission among these patients.

Although the cost of readmissions has been an enduring concern, there has been no previous reports of the costs associated with readmission after SSRF. The two extant studies examining cost-effectiveness of SSRF include a meta-analysis by Swart et al (22) who found an $8,577 incremental cost-effectiveness difference in favor or SSRF, and an analysis by Bhatnagar et al (23) who found that SSRF cost $1,549 less than medical management. However, neither of these studies accounted for the cost of readmission.

We found that the median cost was $14,355 per readmitted patient, which totals $176 million annually. If costs for these readmissions are averaged over all rib fixation patients, the cost of readmissions is $2,349 per treated patient in this study.

Limitations

The NRD is a non-clinical administrative database with limitations inherent to all large data bases. This includes missing data, and differences in coding, specifically among trauma patients. A key limitation of this source is that admissions are not specified as an initial admission for an injury or a follow-up visit. Only temporal proximity is used to define a readmission, so rates of readmission may be not completely accurate. Furthermore, we used clinical experience to categorize causes of readmission based on primary readmission diagnosis. This is a subjective judgement with a high likelihood of misclassification; however, it is the best solution given the limitations of a retrospective study within a non-clinical database. Additionally, a single diagnosis cannot possibly capture the complex picture of an individual patient. We, therefore, reported primarily on all-cause readmission. However, this method lacks the granularity to determine which admissions may have been preventable or not.

This is a retrospective study designed to determine the rate of readmission following SSRF and examine any differences between patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge after SSRF as compared to those who were not readmitted within 30 days of discharge. This study did not attempt to ascertain if patient characteristics, rates of readmission, or reasons for readmission differ between those treated with SSRF as compared to medical management.

Lastly, the NRD does not include Injury Severity Score; therefore, we could not calculate and adjust our results to this variable.

CONCLUSION

Surgical stabilization of rib fracturs has low readmission rates. Primary causes of readmission are most often unrelated to the initial rib fractures or SSRF. Patients with pre-existing medical comorbidities, treated at a smaller hospital, or discharged somewhere other than home are more likely to be readmitted within 30 days after the discharge. Therefore, in order to decrease admission rates, efforts should be focused on optimizing medical comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Janis L Breeze, MPH, for the independent statistical review of the study data.

This study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award UL1TR002544.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey J Aalberg, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

Benjamin P Johnson, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Tufts Medical Center, Boston MA.

Horacio M Hojman, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Tufts Medical Center, Boston MA.

Rishi Rattan, Division of Trauma Surgery & Critical Care, DeWitt Daughtry Family Department of Surgery; Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami FL.

Sandra S Arabian, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Tufts Medical Center, Boston MA.

Eric J Mahoney, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Tufts Medical Center, Boston MA.

Nikolay Bugaev, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Tufts Medical Center, Boston MA.

References

- 1.Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011February;305(5):504–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009April;360(14):1418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Walraven C, Jennings A, Forster AJ. A meta-analysis of hospital 30-day avoidable readmission rates. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012December;18(6):1211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasotakis G, Hasenboehler EA, Streib EW, Patel N, Patel MB, Alarcon L, Bosarge PL, Love J, Haut ER, Como JJ. Operative fixation of rib fractures after blunt trauma: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017March;82(3):618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Moya M, Nirula R, Biffl W. Rib fixation: who, what, when?. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2017April;2(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pieracci FM, Majercik S, Ali-Osman F, Ang D, Doben A, Edwards JG, French B, Gasparri M, Marasco S, Minshall C, et al. Consensus statement: surgical stabilization of rib fractures rib fracture colloquium clinical practice guidelines. Injury. 2017February;48(2):307–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehghan N, Mah JM, Schemitsch EH, Nauth A, Vicente M, McKee MD. Operative stabilization of flail chest injuries reduces mortality to that of stable chest wall injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2018January;32(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman B, De JLM, Andrews R, McKenzie DH. Practical options for estimating cost of hospital inpatient stays. J Health Care Finance, 2002February;29(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald MT, Ashley DW, Abukhdeir H, Christie III DB. Rib fracture fixation in the 65 years and older population: A paradigm shift in management strategy at a Level I trauma center. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017March;82(3):524–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris DS, Rohrbach J, Sundaram LM, Sonnad S, Sarani B, Pascual J, Reilly P, Schwab CW, Sims C. Early hospital readmission in the trauma population: are the risk factors different?. Injury. 2014January;45(1):56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copertino LM, McCormack JE, Rutigliano DN, Huang EC, Shapiro MJ, Vosswinkel JA, Jawa RS. Early unplanned hospital readmission after acute traumatic injury: the experience at a state-designated level-I trauma center. Am J Surg. 2015February;209(2):268–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passman J, Xiong R, Hatchimonji J, Kaufman E, Sharoky C, Yang W, Smith BP, Holena D. Readmissions after injury: is fragmentation of care associated with mortality?. J Surg Res. 2020June;250:209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrey LB, Weddle RJ, Richardson B, Gilder R, Reynolds M, Bennett M, Cook A, Foreman M, Warren AM. Trauma patient readmissions: Why do they come back for more?. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015November;79(5):717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parreco J, Buicko J, Cortolillo N, Namias N, Rattan R. Risk factors and costs associated with nationwide nonelective readmission after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017July;83(1):126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granetzny A, Abd El-Aal M, Emam E, Shalaby A, Boseila A. Surgical versus conservative treatment of flail chest. Evaluation of the pulmonary status. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005December;4(6):583–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker JE, Skinner M, Heh V, Pritts TA, Goodman MD, Millar DA, Janowak CF. Readmission rates and associated factors following rib cage injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019December;87(6):1269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pieracci FM, Leasia K, Bauman Z, Eriksson EA, Lottenberg L, Majercik S, Powell L, Sarani B, Semon G, Thomas B, et al. A multicenter, prospective, controlled clinical trial of surgical stabilization of rib fractures in patients with severe, nonflail fracture patterns. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020February;88(2):249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majercik S, Cannon Q, Granger SR, VanBoerum DH. Long-term patient outcomes after surgical stabilization of rib fractures. Am J Surg. 2014July;208(1):88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarani B, Allen R, Pieracci FM, Doben AR, Eriksson E, Bauman ZM, Gupta P, Semon G, Greiffenstein P, Chapman AJ, et al. Characteristics of hardware failure in patients undergoing surgical stabilization of rib fractures: A Chest Wall Injury Society multicenter study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019December;87(6):1277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junker MS, Kurjatko A, Hernandez MC, Heller SF, Kim BD, Schiller HJ. Salvage of rib stabilization hardware with antibiotic beads. Am J Surg. 2019November;218(5):869–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiels CA, Aho JM, Naik ND, Zielinski MD, Schiller HJ, Morris DS, Kim BD. Infected hardware after surgical stabilization of rib fractures: outcomes and management experience. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016May;80(5):819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swart E, Laratta J, Slobogean G, Mehta S. Operative treatment of rib fractures in flail chest injuries: a meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2017February;31(2):64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatnagar A, Mayberry J, Nirula R. Rib fracture fixation for flail chest: what is the benefit?. J Am Coll Surg. 2012August;215(2):201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.