Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Quantitative studies have documented persistent regional, facility, and racial differences in the intensity of care provided to nursing home (NH) residents with advanced dementia including, greater intensity in the Southeastern US, among Black residents, and wide variation among NHs in the same hospital referral region (HRR). The reasons for these differences are poorly understood, and the appropriate way to study them are poorly described

Design:

Assessment of Disparities and Variation for Alzheimer’s disease Nursing home Care at End of life (ADVANCE) is a large qualitative study to elucidate factors related to NH organizational culture and proxy perspectives contributing to differences in the intensity of advanced dementia care. Using nationwide 2016–2017 Minimum DataSet information, 4 HRRs were identified in which the relative intensity of advanced dementia care was high (N=2 HRRs) and low (N=2 HRRs) based on hospital transfer and tube-feeding rates among residents with this condition. Within those HRRs, we identified facilities providing high (N=2 NHs) and low (N=2 NHs) intensity care relative to all NHs in that HRR (N=16 total facilities; 4 facilities/HRR).

Results/Conclusions:

To date, the research team conducted 275 hours of observation in 13 NHs and interviewed 158 NH providers from varied disciplines to assess physical environment, care processes, decision-making processes, and values. We interviewed 44 proxies (Black, N=19; White, N=25) about their perceptions of advance care planning, decision making, values, communication, support, trust, literacy, beliefs about death, and spirituality. This report describes ADVANCE study design and the facilitators and challenges of its implementation, providing a template for the successful application of large qualitative studies focused on quality care in NHs.

Keywords: dementia, palliative care, hospital transfer, feeding tubes, qualitative methodology

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is the 6th leading cause of death in the United States. Between 2003 and 2017, 58.4% of Americans with dementia died in nursing homes (NHs).1 While comfort is the main goal of care for the majority of these residents,2,3 many receive burdensome and costly interventions that may be of limited clinical benefit.4–13 Quantitative studies conducted over the past 20 years demonstrated striking and persistent regional, facility, and racial differences in the use of two such interventions: hospital transfers and tube-feeding. The reasons for these differences are poorly understood.

Using national data, our group and others described the intensity of advanced dementia care in US NHs, including rates of hospitalizations and tube-feeding, which are highly correlated. These studies consistently show greater intensity of care among Black versus White residents,8,13–20 greater intensity of care in the Southeastern US,15,16,20–26 and marked inter-facility variation even among NHs in the same region.23,27,28 These differences persisted from 2000–2014.8,29

While quantitative studies demonstrate differences in advanced dementia care, they do little to explain them. Qualitative methods have helped elucidate drivers of end-of-life care in the general NH population, however, they have primarily been conducted in small convenience samples, have not leveraged quantitative approaches to purposefully select NHs with disparate practices, neither have they compared NHs in various regions of the country.30,31

Therefore, in June 2018 we began a federally funded, qualitative study entitled ADVANCE (Assessment of Disparities and Variation for Alzheimer’s disease Nursing home Care at End of life) to better understand the drivers of regional and racial variations in the intensity of care provided to NH residents with advanced dementia. The ADVANCE study aimed to explore how NH organization and culture, and the experiences and perceptions of NH staff and resident proxies influence and explain the regional, facility, and racial variations in the intensity of advanced dementia care.

This report presents the unique quantitative methodology used to identify and recruit NHs providing high and low intensity care to advanced dementia residents and the qualitative approaches employed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms for varied care intensity. The paper serves as a reference for future ADVANCE publications as results emerge, and shares lessons learned for future large-scale qualitative studies in the NH setting.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hebrew SeniorLife.

Facility Identification and Recruitment

Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) across the US and NHs within those HRRs were classified as providing either high or low intensity care to NH residents with advanced dementia using nationwide Minimum DataSet 32 assessments from 2016–2017. NHs with at least 85 beds and 10 residents with advanced dementia were included. Advanced dementia residents were those meeting the following eligibility criteria based on MDS assessment closest to April 1, 2016 (±60 days): NH length of stay > 100 days, Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, and severe cognitive impairment defined by a Cognitive Functional Scale score of 4 (range, 0–4, higher score indicates worse impairment).33 To quantify intensity of care at each facility, we determined the proportion of residents with advanced dementia with a feeding tube on that assessment and the number of hospital transfers per resident-year alive over the 12 months following that assessment. These measures were aggregated at the facility and HRR levels.

To select HRRs, we focused on the following states chosen for regional diversity and known state-level variation in advanced dementia care:15,17,22,24,28,34: Alabama (AL), Connecticut, Georgia (GA), Illinois, Louisiana, Massachusetts (MA), New York (NY), Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. HRRs in these states were classified as either low intensity (mean tube-feeding and hospital transfer rates below the median relative to all HRRs nationwide) or high intensity (mean tube-feeding and hospital transfer rates above the median relative to all HRRs nationwide). We then classified all NHs within each HRR as either a high intensity (tube-feeding and hospital transfer rates above the HRR median for both interventions) or low intensity (tube-feeding and hospital transfer rates below the median relative to all other NHs in that HRR) intensity NH.

Our goal was to identify 4 HRRs (two high and two low intensity) and 4 NHs (two high and two low intensity) within each of the 4 HRRs (total 16 NHs). In each state, we focused recruitment efforts in HRRs with the largest number of eligible facilities. Within HRRs, we prioritized NHs that had at least 3 Black residents with advanced dementia estimated with 2016 MDS data. We mailed and emailed study information to the senior administrators of eligible NHs and contacted them by phone 2 weeks later. Whenever possible, we leveraged our relationships with local colleagues to provide introduction to the administrators. NH recruitment in an HRR was complete when two high and two low intensity NHs agreed to participate. NHs were given a Chromebook for their participation.

Nursing Home Staff and Proxies Identification and Recruitment

In all facilities, we aimed to conduct semi-structured interviews with the following staff: director of nursing (N=1), administrator (N=1), social worker (N=1), nurses (N=2), certified nursing assistants (N=2), and medical providers (physicians, physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs)) (N=2). When available, we also hoped to interview speech therapists, dieticians, chaplains, and occupational therapists. Eligibility criteria for staff were: > 21 years, able to communicate in English, and cared for advanced dementia residents for ≥ 2 months. During onsite data collection, administrators introduced the team to eligible staff. If they agreed to participate, an in-person or telephone interview was arranged, verbal informed consent was obtained, and a $25 gift card was given upon completion of the interview.

Eligibility criteria for proxies were: age > 21 years, formal or informal designation as the decision-maker for an advanced dementia resident, and able to communicate in English. We aimed to interview 2 proxies of Black residents and 2 proxies of White residents in each NH. A nurse or social worker asked eligible proxies’ permission for our team to contact them. Interested proxies were contacted to explain the study and arrange an in-person or telephone interview. Verbal informed consent was obtained. Proxies were given a $25 gift card for participating.

Data Collection Protocol and Elements

The data collection team consisted of Black (N=2) and White (N=4) individuals and included trained doctoral students (N=2) and PhD prepared researchers (N=4) overseen by a principal investigator (RPL). Data collectors completed an online training from the EMPaCT (Enhancing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials) Consortium.35 Whenever possible, we paired racially concordant data collectors and interviewees. Data collectors used audio recorders and encrypted, password protected laptops to upload interviews and field notes to Sharefile and to enter quantitative data into REDCap.

Data collection intended to capture factors influencing care of NH residents with advanced dementia from several vantage points including facility culture and organization, staff perceptions, and proxies’ perspectives. Recruitment and data collection were concentrated in one HRR at a time over 6-month period. Each NH had up to 4-week preparatory period, a 4-day on-site data collection period, and a 2-week wrap-up period.

Data collection included the following domains27: facility characteristics, physical environment, care processes, decisions-making processes, and facility explicit and implicit values. 36 Facility characteristics ascertained from the LTC focus database37 included: number of beds, profit status, NP or PA on staff, and the proportions of residents who were Black, female, under 65 years, and on Medicaid. Quality measures from the NH Compare Website included the proportion of long-term care residents with pressure ulcers and the Five-Star Rating (range, 1–5, 5 indicates higher quality).38 Administrators were asked whether the facility had open or closed medical staff, hospice provider contract, and a dementia unit.

Two independent data collectors assessed the physical environment during the site visit using the Observable Indicators of NH Care Quality Instrument (OIQ),39 which consists of 30 questions measuring 7 factors: care delivery, grooming, interpersonal communication, environment-access, environment-basics, environment-homelike, and odors (score range, 0–150; higher scores indicate better quality). Team members also wrote field notes describing the physical environment, noting general atmosphere, odor and noise, private space, presence of chapel, dining facilities and food accessibility, staff interactions with residents, presence of visitors, resident activities, and mealtime environment (cleanliness, odors, furniture, lighting, space for residents and appeal of food).

Data about care processes were ascertained through direct observation and semi-structured interviews with staff (Table 1). Data about mealtime processes were ascertained through non-participant observation and included social interaction during mealtime, meal service, and feeding assistance. Data about decision-making processes for feeding problems and acute illness were collected through semi-structured staff interviews (Table 1). Interviewer queried questions addressed how decisions were made, who was involved, factors influencing decisions, and integration of decisions in care planning. Implicit values were assessed with questions about staff perception of the value of hand feeding, tube feeding, hospital transfer and end-of-life care for residents with advanced dementia. Explicit values, i.e., values expressed to the public, were abstracted from mission statements, brochures, websites, and policies.

Table 1.

Nursing Home (NH) Staff Semi-Structured Interviews: Example questions

| Domains | Feeding | Hospital Transfers |

|---|---|---|

| Care Processes | Describe how you provide care to residents with advanced dementia who experience difficulty eating? What challenges do you face? What strategies do you use? |

Describe how you provide care to advanced dementia residents with an acute medical illness? What is communication like between you and medical care providers/families? What challenges do you face providing acute care/palliative care in the NH? What strategies do you use? |

| Decision-Making Processes | How are decisions related to managing feeding problems typically made? What factors influence these decisions? Who is involved in these decisions? How are decisions about managing feeding problems integrated into advance care planning? | How are decisions around hospital transfers typically made? What factors influence these decisions? Who is involved in these decisions? How are decisions about hospital transfers integrated into advance care planning? |

| Implicit Values | What do you see as the advantages and disadvantages of handfeeding/tube-feeding in advanced dementia? What pressures do you feel from others about how to manage feeding problems? |

What do you see as the advantages and disadvantages to treating acute ill advanced dementia residents in the NH/ hospital? What pressures do you feel from others about where to manage these residents? |

Data describing proxies’ demographics, views, choices, and experiences were ascertained through semi-structured interview based on 9 domains based on the literature40 (Table 2). Proxies were asked about their experiences with and perceptions of advance care planning, decision making related to managing feeding problems and acute illness, preferences and values related to end-of-life care, communication with NH staff and providers, support related to surrogate decision making, trust of staff, understanding of advanced dementia and care decisions, beliefs about dementia and end-of-life care, and the role of religion or spirituality in decision making.

Table 2.

Semi-Structured Proxy Interviews: example questions

| Domain | Example questions |

|---|---|

| Advance care planning | Tell me about your experience talking with NH providers about the type of care [NAME] should receive near the end-of-life. Probe: …about tube-feeding and hospital transfer |

| Decision-making processes | Tell me about treatment decisions you have made for [NAME] recently. Who was involved? What roles did they play? Describe any pressure you felt about deciding one way or another? If you have made decisions about using feeding tubes or going to the hospital for an acute illness, please tell me about those decisions. |

| Preferences and values regarding care | Knowing [NAME] as she was all her life, what do you think would be most important to her at this time with respect to her medical care? How does having or not having this information inform your decision making? |

| Communication with medical team | Describe your experiences communicating with NH providers. What recommendations do you have to help improve their communication with you? |

| Family and community support | Tell me about the support you get family, friends, or your community in your role as caregiver for [NAME]. Do you have enough support? How does support or lack of support influence how you make decisions for [NAME]? |

| Trust | How confident are you that NH providers have [NAME’s] best interest at heart? Do you think that they are taking best care possible of [NAME]? |

| Health literacy | How well do the NH providers explain things to you about [NAME’s] medical problems? How does their ability to explain these things influence how you make decisions for [NAME]? Probe: …about the use of feeding tubes and where to treat acute illnesses |

| Beliefs about illness and dying | What is your understanding of [NAME’s] stage of dementia? How do you think [NAME’s] condition will change in the future? How does [NAME’S] dementia influence the decisions you make; Probe: …about tube feeding and hospital transfer? |

| Religion and spirituality | How do religious or spiritual beliefs influence the decisions you make for [NAME]. Probe: …about the use of feeding tubes and hospital transfer |

Data Analysis

General facility characteristics and participant demographics were characterized using descriptive statistics. The mean total score from the Indicators of NH Care Quality Instrument was calculated for each of the two data collectors, and inter-rater reliability was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Recorded interviews were transcribed and checked for accuracy. Field notes, transcribed interviews, scanned brochures, mission statements, policies, and extracts from NH websites were uploaded to NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd Version 12). The data analytic team included three doctoral students and two doctoral-level investigators (RPL, KMM). A framework analysis methodology was used.41 All transcripts were coded independently by two analysts and interrater reliability assessed using the coding comparison query in NVivo. Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. The analysis consisted of 3 steps: open, thematic, and matrix coding.42 In open coding, the raw data were grouped to create large, discrete themes initially directed by our a priori domains. In thematic coding, these large categories were examined further to identify and refine subthemes. In matrix coding, the themes and subthemes were displayed on two-dimensional matrixes and compared across NH intensity, HRR intensity, and residents’ race.

RESULTS

Results describe our experiences to date implementing the ADVANCE protocol. We provide a brief description of the NHs and participants to illustrate the success of our recruitment and data collection protocol. Major challenges and approaches to overcome challenges are presented and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3:

Strategies to Overcome Challenges Implementing the ADVANCE Protocol

| Challenge | Strategy to Overcome Challenge |

|---|---|

| Nursing Home (NH) Recruitment | |

| Identifying HRRs1 and NHs with varied intensity of advanced dementia care | Used Minimum DataSet to quantify tube-feeding and hospitalizations rates of advanced dementia residents in all US NHs. Focused on 9 states from diverse regions with known variations in care |

| Recruiting 4 NHs in 4 HRRs (total 16 NHs) varied intensity of advanced dementia care | Targeted HRRs with greatest number of high and low intensity candidate facilities. Leveraged connections with local academic and clinical colleagues to introduce our team to NH administrators. Expanded recruitment to adjacent HRR in Georgia with similar intensity of care profile as originally HRR. |

| COVID-19 interruption | Delayed NH recruitment in final HRR. |

| Staff and Proxy Recruitment | |

| Develop trust with staff members | Attended staff meetings, forged relationships with leadership who facilitated staff introductions, “hung out” at nurses’ stations, ate meals with staff, brought food. |

| Recruit staff with varied perspectives | Targeted staff from varied disciplines providing advanced dementia care. Offered $25 incentive. |

| Identify and recruit proxies | Staff introduced research team members to proxies. Offered $25 incentive. |

| Recruit 2 Black proxies in each NH | Used Minimum DataSet to identify NHs with ≥ 3 Black residents. |

| Data Collection | |

| Assure credibility and dependability. | Engaged in observations on various shifts and days, triangulated data sources and data collectors. |

| Be organizationally, culturally, and racially sensitive | Research team members experienced in NH research, staff received structured training in minority research, paired racially concordant interviewers and interviewees. |

| Inability to complete interviews during site visit | Interviews completed by telephone after site visit. |

| Manage complex data from multiple sources | All data collected and linked electronically using multiple platforms (e.g., REDCap, Sharefile, NVivo). |

| COVID-19 interruption | In fourth HRR, proxy and staff interviews were done by phone; on-site data collection deferred. |

| Emotional demand on data collectors | Training and preparation for data collection. Emotional support. Plan to respond to poor-quality care. |

| Qualitative Data Analyses | |

| Need to accurately interpret and validate the experiences of participants | Remain sensitive to the need to incorporate cultural and racial knowledge. Included research team members in discussion and interpretation of findings. |

| Correctly transcribing interviews from interviewees with accents | Transcribers from different backgrounds were employed. |

HRR = Health Referral Region

Facility Recruitment and Characteristics

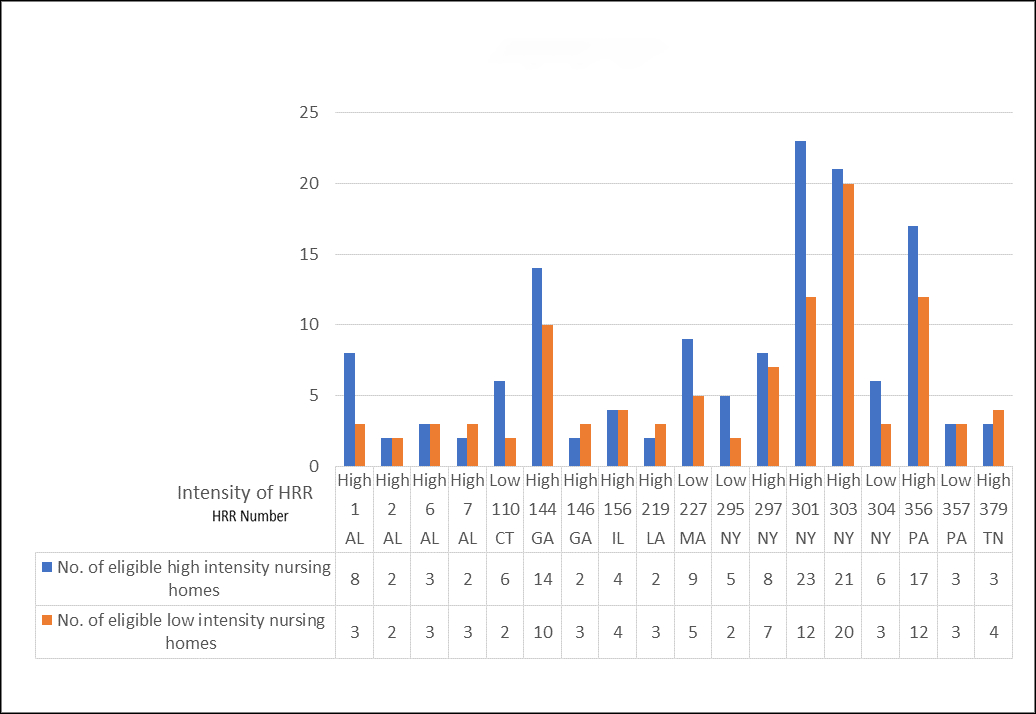

Figure 1 presents the number of high and low intensity HRRs (N=18) in each of the 9 targeted states, and the number of high and low intensity candidate facilities in each HRR. Numeric labels were assigned to HRRs and NHs to protect anonymity. To date, we have recruited and completed data collection in 13 NHs in 4 HRRs (two high and two low intensity). To recruit these facilities, we sent information to 59 NHs, of which 33 administrators did not respond to repeated attempts to be reached by telephone, and 13 refused participation.

Figure.

Candiate Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) and Nursing Homes within Target States

NH recruitment and data collection were completed over 6 months in a low intensity HRR in NY, 4 months in a high intensity HRR in AL and 5 months in high intensity HHRs in GA. In GA, we expanded to an adjacent high intensity HRRs to recruit a fourth NH. In the AL HRR, we were only able to recruit 3 NHs but plan to return to recruit the fourth. In a low intensity HRR in MA, recruitment was delayed due to COVID-19, reinitiated with remote interviews in August 2020, and onsite data collection will recommence once COVID-19 restrictions are lifted.

Table 4 presents the characteristics of the 13 participant NHs. In terms of intensity of care, in the high intensity NHs in the high intensity HRRs, the % tube-fed residents ranged from 12.6%−44.3%, and hospital transfer rates per resident-year alive ranged from 0.6–1.6. In contrast, in high intensity NHs in low intensity HRRs, the % tube-fed residents ranged from 3.3%−5.3%, and hospital transfer rates per resident-year ranged from .04–0.8. In low intensity NHs in high intensity HRRs, the % tube-residents ranged from 0.0%−15.1%, and hospital transfer rates ranged from 0.1–0.7. In low intensity NHs in low intensity HRRs, the % tube-fed residents were 0.0 and hospital transfer rates ranged from 0.0–0.2.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Recruited Nursing Homes (N=13)

| Characteristic | HRR, New York (low intensity) | HRR, Alabama (high intensity) | HRRs, Georgia (high intensity) | HRR, Massachusetts (low intensity) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH 192 (high) | NH 195 (high) | NH 196 (low) | NH 198 (low) | NH 13 (high) | NH 25 (low) | NH 27 (low) | NH 38 (high) | NH 48 (high) | NH 58 (low) | NH 59 (low) | NH 88 (low) | NH 81 (high) | |

| Intensity of Care | |||||||||||||

| % advanced dementia resident tube-fed | 4.6 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.7 | 33.3 | 15.1 | 44.3 | 12.6 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 3.3 |

| hospital transfer for advanced dementia residents/person-year | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Organizational | |||||||||||||

| No. Beds a | Small | Large | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Small | Large | Small | Small | Medium | Small | Large |

| For profit | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Urban (versus rural) location | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| NP/PA on staff | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Dementia unit | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Open or closed medical staff | Open | Closed | Closed | Closed | Open | Open | Open | Open | Open | Open | Open | Open | Open |

| Contract with hospice provider | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Resident | |||||||||||||

| % Black | 33.3 | 4.9 | 22.8 | 4.9 | 33.3 | 29.3 | 10.3 | 71.6 | 14.8 | 5.2 | 14.5 | 8.4 | 7.2 |

| % Female | 35.2 | 75.2 | 71.6 | 75.2 | 73.5 | 77.3 | 81.4 | 53.5 | 80.4 | 66.1 | 70.9 | 64.2 | 67.1 |

| % < 65 years | 30.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 15.9 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 30.3 | 6.9 | 2.6 | 19.7 | 14.7 | 7.9 |

| % Medicaid | 77.2 | 62.5 | 64.7 | 60.7 | 70.3 | 70.0 | 57.3 | 81.3 | 73.0 | 45.2 | 81.1 | 58.8 | 81.2 |

| Quality Measures | |||||||||||||

| % Long stay with pressure ulcers | 5.3 | 8.5 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 1.2 | 19.0 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| NHC Star Rating b | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Mean total OIQ score c, d | 56 | 105 | 114 | 101 | 94 | 93 | 104 | 78 | 107 | 135 | 106 | N/A | N/A |

Abbreviations: HRR = Hospital Referral Region; NH = Nursing Home; NP = Nurse Practitioner; PA = Physician Assistant; NHC = Nursing Home Compare

Bed sized categorized based on distribution of sample. Small = 85–125 Medium = 126–200, Large >200

Nursing Home Compare Five-star rating; range 0–5, higher scores indicate better care quality

Observable Indicators of Quality: Score equal to or above 128 suggests a high quality nursing home, score equal to or below 103 suggests a low nursing home with quality issues, scores between these numbers are typical of most nursing homes

Average score of two independent data collectors’ ratings

Among the 13 participating facilities, 9 were for profit, 10 had an NP/PA on staff, and 12 contracted with hospice providers. Resident characteristics demonstrated wide variability in percent Black residents (range, 4.9%–71.6%). One NY facility was notable for a relatively lower proportion of female residents and high proportion of residents under 65, as it served an atypical NH population with a very high prevalence of prior homelessness, severe mental health issues, and substance abuse.

Primary Data Collection

Teams of 2–3 data collectors conducted 4-day on-site visits to participating NHs in NY, GA, and AL. In the MA HRR, 2 data collectors conducted telephone interviews with staff and proxies. The team spent approximately 275 hours conducting on-site visits (range per NH, 20–28 hours), and observed breakfasts (N=20), lunches (N=21) and dinners (N=22). The mean OIQ score from all facilities ranged from 56–135 and an inter-rater reliability of 0.79 indicating substantial agreement. The research team established trust with the NH staff by forging relationships with senior staff members, attending morning staff meetings, “hanging out” at nurses’ stations, and eating meals with staff whenever possible. Credibility was met by engaging in lengthy and intensive observations on various shifts, weekdays, and weekends, triangulating data sources and triangulating data collectors.

To date, we conducted 158 staff interviews of which 132 were in-person and 26 by telephone (range, 11–13 per NH). Interviews averaged 34 minutes (range, 10 to 70 minutes). Disciplines included: director of nursing, N=12; senior administrator, N=12; social worker, N=14, occupational therapist, N=7; speech therapist, N=11; physical therapist, N=3, recreational therapist, N=3; licensed nurse, N=43, nursing assistant, N=23; dietician, N=10; medical provider, N=16; and chaplain, N=4. Although some staff became emotional when talking about death of residents, none refused to answer questions or became very distressed. Most expressed appreciation for being asked to participate.

We conducted 44 proxy interviews; 20 were conducted in-person and 24 by telephone. Proxies were spouses, N=5; children, N=25; other family, N=12; and legal guardians, N=2. Nineteen proxies were Black and 25 were White. In 7 NHs we were able to recruit 2 White and 2 Black proxies. The distribution of proxy recruitment in the remaining NHs were: 1 White and 1 Black, N=1 NH; 2 White and 1 Black, N=2 NHs; and 3 White and 1 Black, N=2 NHs. We were unable to recruit any proxies in one NH in the MA HRR during the COVID pandemic. Proxy interviews averaged 34.7 minutes, (range, 15 to 52 minutes). Although some proxies expressed sadness or anger directed at care providers or NHs, none refused to answer questions or became very distressed.

Qualitative Analysis

Nearly 60 hours of interviews were professionally transcribed to improve accuracy of transcriptions from interviews with participants with diverse, regional accents. The analytic team verified each transcript for accuracy, removed identifiers, and uploaded to NVivo. Scanned brochures (N=11), mission statements (N=11), policies (N=11), and extracts from NH websites (N=12) and field notes were uploaded to NVivo. After completion of data collection in the first HRR (NY), the analytic team met 3 hours each week, developed an initial codebook, and coded all interviews and observations. During analysis of the second HRR (AL), new codes emerged requiring revision of the codebook, and recoding the first HRR. Thereafter, the codebook did not require revision. To manage the large volume of data, one team member served as the data manager, merging files, conducting coding comparisons, and leading consensus discussions. Diverse perspectives were encouraged while remaining focused on the study’s specific aims. To date, all data has been open and thematic coded and matrix coding is in process to compare themes across NH intensity, HRR intensity, and residents’ race.

DISCUSSION

This underlying reasons for the racial and regional variations in care of NH residents with advanced dementia are not well understood and complex. This qualitative study was designed to tease out the regional factors, facility organization characteristics, staff perspectives, and proxy beliefs driving these variations. To meet this challenge, ADVANCE leveraged national databases to establish the framework necessary to identify and recruit NHs providing high and low intensity care to NH residents with advanced dementia within and across HRRs. Further, we implemented an intensive primary data collection effort using multiple data collection methods and sources to better understand these observed variations in care. Taken together, the ADVANCE data will provide a unique rich resource allowing us to compare and contrast drivers of advanced dementia care associated with race, region, and NH organizational culture.

In the last two decades, NH health services research in U.S. has benefited from routinely collected standardized data sources, such as the MDS, that allow for detailed characterization of residents and facilities nationwide. These unique data sources enabled us to purposefully select HRRs and NHs within HRRs providing varied intensity of care to residents with advanced dementia. The ‘a priori’ knowledge of the NHs’ and HRRs’ intensity of care practices will provide context to interpret our qualitative findings and help disentangle complex relationships. For example, contrasting NHs which provide high and low intensity of care within a single HRR allows us to explore how facility culture and organizational features drive practice independent from regional or local market factors.

Our timeline of 6 months to recruit and complete data collection in 4 NHs in a single HRR was ambitious.43 The national quantitative data characterizing facilities allowed us to concentrate our efforts in HRRs with the largest number of candidate NHs and helped identify a neighboring high intensity HRR to meet our facility recruitment goals in GA. We also gave preference to HRRs in which we could leverage local colleagues to facilitate introductions to NH administrators. This approach was a pragmatic and ultimately successful but was also limited in that it excluded rural facilities. Nonetheless, we successfully recruited NHs with a range of characteristics.

We strove to recruit 2 White and 2 Black residents in the high and low intensity facilities. We met these targets in 7 facilities but only recruited 1 Black proxy in 5 NHs, largely due to a small number of Black residents rather than proxy refusals. Although we prioritized recruitment of NHs with at least 3 Black residents with advanced dementia estimated with 2016 MDS data, the demographic profile may have shifted in the interim. Nursing assistants, nurses, medical providers, social workers, and senior administrators were interviewed in almost all facilities. However, in some facilities, we were unable to reach staff from certain disciplines that are typically represented by only one or two individuals (e.g., speech therapists). Commonly cited barriers to NH staff participation in research include time burden, staff turnover, and mistrust. 44–47 We were able to circumvent these barriers as ADVANCE entailed minimal time commitment and provided an opportunity for participants to share their experiences on a topic they considered important.

The comprehensive data collection for this study required an intensive effort. We successfully employed several qualitative approaches including prolonged engagement, triangulation, and team debriefing to assure credibility and dependability.48 We ensured research team members were racially and regionally congruent, had NH research experience, and completed standardized training for conducting research in minority populations.35 One unanticipated challenge was the emotional reactions data collectors experienced from witnessing poor quality care (e.g., residents fed too quickly, broken windows, thin bed clothes, dirty environment). This phenomenon, aptly termed “compassion stress,” has been under-reported in NH qualitative research.49,50 Advance preparation, counseling, peer debriefing, and journal writing are suggested strategies for managing compassion stress. Having clear protocols for reporting suspected elder abuse in qualitative research involving vulnerable older persons is also warranted.

Limitations encountered in ADVANCE merit comment. First, we recruited 2 proxies of Black residents in most, but not all, facilities. US NHs tend to be highly segregated along racial lines. While this phenomenon underlies the very questions ADVANCE seeks to explore, it also limited our ability to recruit Black proxies in predominantly White NHs. Second, our findings may not be generalizable to NHs in rural settings. Third, COVID-19 pandemic interrupted data collection in our final HRR. However, we are confident that data are sufficiently robust to answer our study aims. Additionally, with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Aging, we are leveraging the ADVANCE infrastructure to explore additional research questions regarding advanced dementia care during the pandemic.

The ADVANCE study design and protocol provided a successful template for carrying out a large, qualitative studies in diverse NHs. It underscored the utility and feasibility of using national databases to purposefully identify and recruit facilities. Our experience demonstrates it is possible to collect and manage a huge amount of multi-source, complex, qualitative data. Importantly, it further underscored the need to prepare data collectors for the potential emotional response to qualitative data collection, particularly for vulnerable populations. The remaining challenge is the forthcoming analyses of the massive qualitative dataset, to successfully elucidate the drivers of the racial and regional differences in end-of-life care provided to NH residents with advanced dementia.

Key Points

Differences in burdensome care for nursing home residents with advanced dementia exist.

We used a qualitative design to elucidate organizational culture and proxy perspectives contributing to these differences.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

The design provides a template for similar studies focused on quality in nursing homes.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG058539. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Sponsor’s Role: Sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

A paper describing the ADVANCE methodology was presented at the Gerontological Society of American Annual Meeting 2020 Dec 16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cross SH, Kaufman BG, Taylor DH Jr., Kamal AH, Warraich HJ. Trends and Factors Associated with Place of Death for Individuals with Dementia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Agata E, Mitchell SL. Patterns of antimicrobial use among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Givens JL, Jones RN, Shaffer ML, Kiely DK, Mitchell SL. Survival and comfort after treatment of pneumonia in advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1102–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez RP. Suffering and dying nursing home residents: Nurses’ perceptions of the role of family members. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2007;9(3):141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell SL, Mor V, Gozalo P, Servadio JL, Teno JM. Tube feeding in US nursing home residents with advanced dementia, 2000–2014. Jama. 2016;316(7):769–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Loeb MB, et al. Infection management and multidrug-resistant organisms in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Kuo S, Fulton AT, Mor V. Feeding tubes and the prevention or healing of pressure ulcers. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172(9):697–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Mitchell SL, et al. Does feeding tube insertion and its timing improve survival? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1918–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Khandelwal N, et al. Association of increasing use of mechanical ventilation among nursing home residents with advanced dementia and intensive care unit beds. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1809–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(3):327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connolly A, Sampson EL, Purandare N. End-of-life care for people with dementia from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulton AT, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Intensive care utilization among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive and severe functional impairment. Journal of palliative medicine. 2014;17(3):313–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gessert CE, Mosier MC, Brown EF, Frey B. Tube feeding in nursing home residents with severe and irreversible cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(12):1593–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Archives of internal medicine. 2001;161(4):594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen JE, Goode KT, Haley WE. End of life care and reactions to death in African-American and white family caregivers of relatives with Alzheimer’s disease. Omega. 2001;43(4):349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, et al. Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertion: a five-state study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(5):881–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahronheim JC, Mulvihill M, Sieger C, Park P, Fries BE. State practice variations in the use of tube feeding for nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(2):148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gessert CE, Haller IV, Kane RL, Degenholtz H. Rural-urban differences in medical care for nursing home residents with severe dementia at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(8):1199–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, Kabumoto G, Mor V. Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290(1):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, et al. Churning: the association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):359–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teno JM, Mor V, DeSilva D, Kabumoto G, Roy J, Wetle T. Use of feeding tubes in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Jama. 2002;287(24):3211–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Gozalo PL, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2010;303(6):544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez RP, Amella EJ, Strumpf NE, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Archives of internal medicine. 2010;170(1):83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Gillick MR. Nursing home characteristics associated with tube feeding in advanced cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell SL, Mor V, Gozalo P, Servadio JL, Teno JM. Tube-Feeding in US Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia, 2000–2014. Paper presented at: Academy Health2016; Boston, MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallace CL, Adorno G, Stewart DB. End-of-life care in nursing homes: A qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Journal of palliative medicine. 2018;21(4):503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malnutrition Kayser-Jones J., dehydration, and starvation in the midst of plenty: the political impact of qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(10):1391–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medicare Cf, Services M. Draft Minimum Data Set, version 3.0 (MDS 3.0). Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Medical Care. 2017;55(9):e68–e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levinson DR. Medicare Nursing Home Resident Hospitalization Merit Additional Monitoring In: General HaHSOotI, ed. Vol OEI-06–11-000402013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Initiative for Minority Involvement in Neurological Clinical Trials. Enhancing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials (EMPaCT). http://nimict.com/tools/enhancing-minority-participation-in-clinical-trials-empact/. Accessed2020.

- 36.Lopez RP, Amella EJ, Strumpf NE, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(1):83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaping Long Term Care in America Project at Brown University. LTC focus. http://ltcfocus.org/. Published 2009–2020. Accessed2020.

- 38.Services USCfMM. Medicare.govNursing Home Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/search.html?Published 2020. Accessed2020.

- 39.Rantz MJ, Aud MA, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, et al. Field testing, refinement, and psychometric evaluation of a new measure of quality of care for assisted living. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2008;16(1):16–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders JJ, Robinson MT, Block SD. Factors impacting advance care planning among African Americans: Results of systematic integrated review. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016;19(2):202–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC medical research methodology. 2013;13(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shepherd V, Nuttall J, Hood K, Butler CC. Setting up a clinical trial in care homes: challenges encountered and recommendations for future research practice. BMC research notes. 2015;8(1):306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies SL, Goodman C, Manthorpe J, Smith A, Carrick N, Iliffe S. Enabling research in care homes: an evaluation of a national network of research ready care homes. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elkins KR, Nguyen CM, Kim DS, Meyers H, Cheung M, Huang SS. Successful strategies for high participation in three regional healthcare surveys: an observational study. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia C, Kelley CM, Dyck MJ. Nursing home recruitment: trials, tribulations, and successes. Applied Nursing Research. 2013;26(3):136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore DC, Payne S, Van den Block L, ten Koppel M, Szczerbińska K, Froggatt K. Research, recruitment and observational data collection in care homes: lessons from the PACE study. BMC research notes. 2019;12(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New directions for program evaluation. 1986;1986(30):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rager KB. Compassion stress and the qualitative researcher. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(3):423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lalor JG, Begley CM, Devane D. Exploring painful experiences: impact of emotional narratives on members of a qualitative research team. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;56(6):607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]