Abstract

The late Pleistocene settlement of highland settings in mainland Southeast Asia by Homo sapiens has challenged our species’s ability to occupy mountainous landscapes that acted as physical barriers to the expansion into lower-latitude Sunda islands during sea-level lowstands. Tham Lod Rockshelter in highland Pang Mapha (northwestern Thailand), dated between 34,000 and 12,000 years ago, has yielded evidence of Hoabinhian lithic assemblages and natural resource use by hunter-gatherer societies. To understand the process of early settlements of highland areas, we measured stable carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of Tham Lod human and faunal tooth enamel. Our assessment of the stable carbon isotope results suggests long-term opportunistic behavior among hunter-gatherers in foraging on a variety of food items in a mosaic environment and/or inhabiting an open forest edge during the terminal Pleistocene. This study reinforces the higher-latitude and -altitude extension of a forest-grassland mosaic ecosystem or savanna corridor (farther north into northwestern Thailand), which facilitated the dispersal of hunter-gatherers across mountainous areas and possibly allowed for consistency in a human subsistence strategy and Hoabinhian technology in the highlands of mainland Southeast Asia over a 20,000-year span near the end of the Pleistocene.

Subject terms: Ecology, Evolution, Biogeochemistry

Introduction

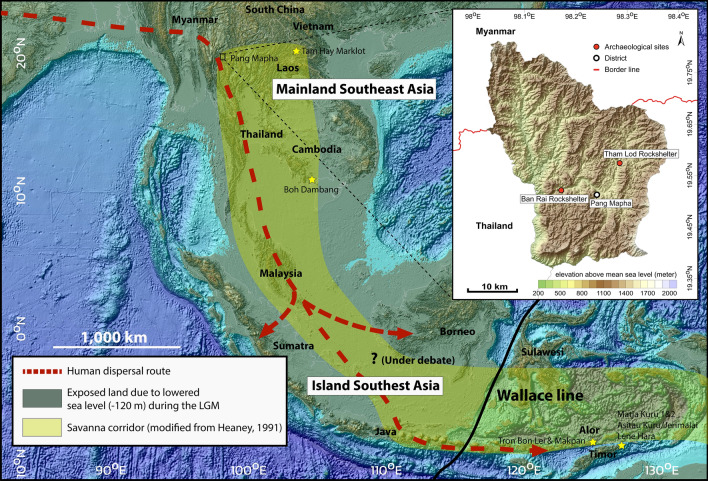

Our species has spread worldwide and successfully occupied a diversity of extreme environments such as deserts, arctic environments, tropical rainforests, and high-altitude conditions during the late Pleistocene (126–12 ka) (1). During the process of dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa to ultimately reach Australia, mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA) is recognized as being a potential route of human migration prior to crossing through the Sunda Shelf during a period of glaciation (Fig. 1). In terms of paleoenvironments, much botanical, biogeographical, and geochemical evidence has suggested that a north–south savanna corridor (i.e. a band of open vegetation or a mixture of forest/grassland ecosystem) was present, starting from the central part of Thailand and streching across the exposed Sunda shelf during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, around 29–17 ka) when the sea level dropped up to 120 m below the present-day stand (e.g.,2–5). Such a corridor might have facilitated the rapid dispersal of early humans through the intermediate migratory region of SEA4,6. However, the range expansion of inland vegetation examining the northern limit of a savanna corridor during the LGM is not yet known in great detail and the past human–environment interactions in the highlands of MSEA remain barely understood. Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental studies of the late Pleistocene hominin-bearing faunas in MSEA are thus important to understand the early modern human mobility and migration patterns through the land corridor into island Southeast Asia (ISEA).

Figure 1.

Map of Southeast Asia showing the location of archaeological sites in Pang Mapha, Mae Hong Son Province, northwestern Thailand and indicating the dispersal route of early modern humans (red dashed line, modified from7) and the extension area of a hypothesized north–south savanna corridor (yellow area) during the LGM (modified from2). The continuity of the band of open vegetation existing along the transequatorial region of central Sundaland remains under debate (e.g.,4,8–10) (see4,6,10 for other detailed information and available proxy data regarding the LGM vegetation cover across Southeast Asia). Stars indicate the location of late Pleistocene fossil sites where stable isotope analyses of mammal tooth enamel have been performed. The map was generated in Surfur software (version 11, https://www.goldensoftware.com) and the figure was created using Adobe Illustrator CS5 (https://www.adobe.com).

Mainland Southeast Asia has yielded a high number of archaeological sites with rich animal remains and lithic artifacts, although human remains were rarely found in association with them especially during the late Pleistocene (e.g.,11–19). The earliest modern human fossils, dated to a minimum age of 63–43 ka, were recovered from Tam Pa Ling, up to 1170 m in elevation, in Laos16,17. The increasing number of archaeological records in Thailand and Laos also supports the idea that high-altitude karst settings such as caves and rockshelters (e.g., Spirit Cave, Tham Lod Rockshelter, Ban Rai Rockshelter, Doi Pha Kan, and Pha Phen) were often used by hunter-gatherers14,15,20–23. Chrono-cultural frameworks for human remains and stone artifacts recovered from many archaeological sites in MSEA have suggested a typical “Hoabinhian” techno-complex characterized by flexed burials, sumatraliths, large and small tools made on cobbles, with an age ranging from the late Pleistocene to the mid-Holocene (e.g.23–27). A highland area (a range of low mountains or elevated parts of the country) is topographically characteristic of northern Thailand, which shares borders with Myanmar and Laos. Tham Lod Rockshelter (TLR) in Pang Mapha District (Mae Hong Son Province, northwestern Thailand) situated on a mountainous karst landscape with the elevation of 640 m above mean sea level (Fig. 1) is a good example of such important highland sites where the human and animal remains associated with the Hoabinhian techno-complex have systematically been excavated with available and detailed stratigraphic, taphonomic, zooarchaeological, and chronological data14,15,26,28–31. Radiocarbon (14C) and thermoluminescence (TL) dating methods on various material including charcoal, sediments, and freshwater shells collected along the stratigraphic section of TLR have provided measurements for the faunal age ranging from 34 to 12 ka14,15,28,29 (Fig. 2 and see Supplementary Information 1 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for more detailed information on geological, dating, faunal, and zooarchaeological contexts). The rockshelter was initially occupied by hunter-gathers since 34 ka14,15, while the human skeletal remains were recovered only from the upper part of the TLR stratigraphic sequence (layers 3, 4, 5, and 12 in the Area 1), dated between 19 and 12 ka (Fig. 2). The zooarchaeological analyses of a mammalian assemblage and the detailed studies of lithic assemblages in TLR have provided some information about subsistence patterns of hunter-gatherers in the area26,29–31. However, based on these approaches alone, it is difficult to describe properly the ecological niche of late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer populations and to refine the relationship between lithic technology and paleoenvironments in the highland of MSEA. More direct investigations of human resource reliance, using other multidisciplinary methods, are thus required.

Figure 2.

A plan of excavations and stratigraphic profile of the Area 1 of Tham Lod Rockshelter. Ages of each stratigraphic layer obtained from different dating methods and material14,15,28,29 are plotted together. In this study, all isotope samples of humans and mammals were collected from the layer 1 (top) to 31 (bottom) of the TLR Area 1. The figure was created using Adobe Illustrator CS5 (https://www.adobe.com).

To understand resource-exploitation strategies of early humans, an isotopic approach applied to faunal fossilized tissues has proven to be useful in reconstructing the diet and habitat of ancient mammals as well as the paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic contexts for human occupations (e.g.,32–35). Although carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements of dentine collagen of a few late Pleistocene mammals (38.4–13.5 ka) from the cave of Tam Hay Marklot in northern Laos have successfully been carried out36, stable isotope tracking on dentine or bone collagen of human and animal remains from several archaeological sites in MSEA has been rather limited likely due to their location under the tropical monsoon climate where warm temperature and humidity usually prevented the good preservation of biological molecules such as DNA and collagen (e.g.,37,38). In the case of TLR, faunal remains exhibited poor collagen preservation as indicated by the low amounts of nitrogen content (using a CNS analysis) of several dentine and bone samples (Supplementary Tables S3). Alternatively, measurements of stable carbon and oxygen isotope ratios in tooth enamel are one of the most efficient tools available to address this issue. So far, this approach has never been applied directly to the paleoecological study of any human-bearing faunas with this age range in MSEA.

Here we performed stable carbon and oxygen isotope analyses of human and faunal tooth enamel collected from the Area 1 of TLR (Fig. 2). The aim of this study is to investigate the ecological niche of late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer populations and their associated mammal assemblages and to determine the role of faunal resources and local environments on human exploitation strategies in the region. In the light of stable isotope data, we propose an environmental scenario for the process of early modern human settlements of highland SEA with implications for the dispersal of Homo sapiens across MSEA during the LGM.

Results

Isotope analysis of tooth enamel

The CaCO3 content of all TLR enamel samples (n = 195) varies from 2.0 to 6.9% and falls mostly within the normal range of recent samples that do not show evidence of diagenetic effects (e.g.,39) (see Supplementary Table S4 for a stable isotope dataset). Although some high values may reflect a minor contribution of isotopic exchanges with exogenous sedimentary carbonates, there is no correlation between CaCO3 content and δ13C and δ18O values for those samples (Supplementary Fig. S1). Therefore, there is no indication that the pretreated enamel samples have not yielded biogenic isotope signals.

Carbon isotope results are interpreted based on estimated cut-off values for diets of C3 versus C4 (grasses or sedges) plants and for habitats of closed versus open canopies. In the humid tropics, the cut-off δ13C values of − 10‰ and − 2‰ are applied for the dietary category distinction between herbivorous ungulates (< − 10‰ for a pure C3 diet, between − 10‰ and − 2‰ for a mixed C3/C4 diet, and > − 2‰ for a pure C4 diet)34,40,41. In terms of habitats, the cut-off δ13C values lower than − 13‰ refer to the browsers that occupied a closed forest canopy, while the cut-off δ13C values higher than − 10‰ indicate a mixed feeder and/or grazer in more open habitats (e.g.,35,41). In terms of trophic relationships, all δ13C values of predators present in this study (i.e. Panthera tigris) are adjusted upward by + 1.3‰ for a direct comparison with those of herbivores42,43). In omnivores such as some primates (including humans), rodents (i.e. Hystrix), and ursids (i.e. Ursus thibetanus), stable carbon isotopes in tooth enamel are incapable of distinguishing between plant- and meat-based (or insect-based) diets and the carbon isotopic fractionation between their food and tooth enamel remains unclear. In this study, we keep reporting enamel δ13C values of omnivores without isotopic fractionation corrections, which may not allow us to compare directly the trophic relationships between omnivores and herbivores/carnivores. The isotopic enrichment of 13C between diet and bioapatite in omnivorous mammals varies among species likely due to differences in their body sizes and physiological, anatomical, and behavioural traits (e.g.,44,45). However, the δ13C values of omnivores can reflect the dietary intake of the ultimate plant resources (C3 or C4)46.

The δ18O carbonate of tooth enamel is commonly used to investigate the isotopic composition of ingested water, despite having been influenced by several important factors (e.g., latitude, altitude, aridity, precipitation, and evaporation). As the oxygen isotopic fractionation of meteoric water is incorporated into the animal's tissues via obligate drinking and/or plant-derived intake, some principles are often applied to the study of fossil mammals within the same temporal and spatial coverage. Mammals frequently ingesting water through drinking are expected to have lower δ18O enamel values than those of drought-tolerant taxa47,48. Grassland-inhabiting grazers may have higher δ18O enamel values than forest-dwelling browsers35,49.

Bulk isotope analysis

All the δ13C values of human and mammal tooth enamel displayed a median of − 4.3‰ and ranged from − 16.0‰ to + 4.7‰, indicating reliance on a broad range of ecosystems expanding from pure C3 to C4 vegetation and corresponding to dense forests to open environments (Fig. 3). The enamel carbonate δ18O values of all human and faunal samples exhibited a median of − 6.6‰ and ranged from − 11.4‰ to + 0.1‰. Statistically examined by the Kruskal–Wallis tests, there are significant differences in median δ13C and δ18O values between the investigated mammalian groups (δ13C: H = 138.80, P < 0.01 and δ18O: H = 32.51, P < 0.01, n = 174) (see Supplementary Table S5 for Mann–Whitney pairwise comparisons between taxa).

Figure 3.

Box plots of bulk δ13C (blue) and δ18O (orange) values of human and faunal tooth enamel from the late Pleistocene of Tham Lod Rockshelter in highland Pang Mapha, northwestern Thailand. Asterisks (*) indicate carnivorous mammals with adjusted δ13C values of + 1.3‰ according to42,43.

δ13C

Omnivore

Primates The δ13C values of Macaca sp. (median: − 15.1‰, range: − 16.0‰ to − 1.9‰, n = 8) suggested the consumption of pure C3-based resources in dense forest environments. One peculiar sample with a C4 signal (− 1.9‰) suggests that some individuals were able to consume grasses or possibly ate chiefly grass-eating insects such as grasshoppers, as observed in the feeding habits of extant long-tailed macaques in Malaysia and Java50,51.

Humans The δ13C values of human teeth (median: − 10.2‰, range: − 14‰ to − 9.4‰, n = 5) almost suggested the consumption of a combination between the higher amount of C3 foods (plants and/or C3 plant-dwelling preys) and some C4 items and/or the occupation in open forests (more open habitats compared to Macaca sp., P < 0.05). The most negative δ13C value of − 14‰ in the tooth sample collected from the layer 3 near the ground surface showed human reliance on pure C3-based resources in a closed forest canopy.

Rodents The δ13C values of Hystrix sp. (median: − 13.3‰, range: − 15.3 to − 11.4‰, n = 11) suggest that porcupines consumed only pure C3-based resources in closed or open canopy forests, which were not as dense as where the macaques occupied (P < 0.05). The δ13C values of small indeterminate rodents (median: − 11.0‰, range: − 13.8‰ to − 0.4‰, n = 8) yielded a high variability in dietary intake and habitat use ranging from closed C3 to open C4 ecosystems (P > 0.05 between indeterminate rodents and humans).

Omnivorous Carnivora Ursus thibetanus (median: − 13.5‰, range: − 15.3‰ to − 3.5‰, n = 25) might have had the primary diet of C3 food items (e.g., fruits from trees as well as insects, invertebrates, and small vertebrates that ate C3 plants) similar to that of extant populations52, and shared a closed habitat with the porcupines (Hystrix sp.) (P > 0.05) and some ruminants such as small-sized deer Muntiacus sp. and Axis porcinus. One sample of Arctonyx collaris (− 10.9‰) reflected its food preferences on C3 items such as tubers, roots, and small creatures52 and its occupation of an open forest landscape.

Suids Samples of Sus scrofa (median: − 7.6‰, range: − 11.1‰ to − 3.1‰, n = 14) imply that their diet consisted of a mixture of C3 and C4 resources in an intermediate area between open and closed landscapes or sometimes had a pure C3 diet in an open forest. This also indicates that both types of vegetation were available at the same time and in a limited area.

Carnivore

Predatory Carnivora The adjusted δ13C values of Panthera tigris (median: − 10.2‰, range: − 11.7‰ and − 4.7‰, n = 3) suggest that tigers were probably preying essentially on S. scrofa or might have been consumers of a wide range of prey species in both open and closed canopies.

Herbivore

Elephants One sample of Elephas sp. exhibited a δ13C value of − 4.7‰, which suggested a mixture of C3 and C4 plants in an intermediate area between closed and open canopy landscapes.

Rhinoceroses The rhinocerotid enamel samples (median: − 0.1‰, range: − 14.6‰ to + 1.0‰, n = 3) suggested a wide range of diets varying from pure C3 to C4 vegetation. Otherwise, it is possible that there were two separate rhinocerotid taxa in the locality, one C3 browsing species (e.g., Rhinoceros sondaicus) and two C4 grazing individuals (e.g., Rhinoceros unicornis), as observed in some Pleistocene Southeast Asian sites53.

Cervids The small-sized muntjac deer, Muntiacus sp. (median: − 12.6‰, range: − 13.7‰ to − 12.3‰, n = 3), had pure C3-plant diets and occupied a forest landscape, similar to the extant population of Muntiacus muntjak (Indian muntjac)52. The samples of Axis porcinus (median: − 13.8‰, range: − 14.7‰ to − 12.6‰, n = 3) indicated a pure C3 plant diet in more closed canopy habitats, compared to Muntiacus sp. The Eld's deer Rucervus eldii (median: + 2.7‰, range: + 1.5‰ to + 3.4‰, n = 11) had a pure C4 diet and occupied an open habitat. The sambar deer Rusa unicolor (median: − 2.6‰, range: − 6.2‰ to + 2.0‰, n = 35) indicated their primary utilization of mixed C3/C4 plants but sometimes pure C4 ones and had the occupation of open canopy habitats but more closed than where Rucervus eldii lived (P < 0.05). Unlike their modern representatives that have a habitat shift to more closed forests10,52, the late Pleistocene Rucervus eldii and Rusa unicolor in TLR were reliant on an open grassland landscape. It is apparent that substantial resource partitioning and minimized intergeneric competition occurred among TLR cervid communities, leading to the prevalent coexistence of four cervid genera/species during the late Pleistocene.

Bovines Samples of wild water buffaloes, Bubalus arnee, (median: + 3.0‰, range: + 0.3‰ to + 4.7‰, n = 5) reflected a pure C4-plant diet. Two large bovid species, Bos javanicus (median: + 2.4‰, range: + 1.5‰ to + 2.8‰, n = 3) and Bos gaurus (median: + 1.0‰, range: − 0.9‰ to + 3.4‰, n = 13), consumed substantial amounts of C4 plants, similar to Bubalus arnee (P > 0.05). The samples of undetermined species, Bos sp. (median: + 2.1‰, range: + 2.0‰ to + 3.2‰, n = 4) also focused on pure C4 vegetation in an open habitat.

Caprines Stable isotope data of two goral taxa (Chinese goral Naemorhedus griseus and Himalayan goral Naemorhedus goral) and one serow species (sumatran serow Capricornis sumatraensis) from TLR were analyzed by54. Both Naemorhedus griseus (median: − 0.4‰, range: − 7.1‰ to + 1.9‰, n = 19) and Naemorhedus goral (median: − 3.3‰, range: − 5.3‰ to − 0.1‰, n = 8) showed the same dietary habits in foraging on mixed C3 and C4 vegetation and on pure C4 plants (P = 0.05)54. However, Capricornis sumatraensis (median: − 12.2‰, range: − 14.3‰ to + 1.9‰, n = 12) had a wider range of diets, compared to the two goral species (P < 0.05), reflecting its occupation of closed C3- to open C4-dominated landscapes54.

δ18O

Several samples from the same taxa/locality showed a high variability and relatively wide ranges of δ18O values (Fig. 3) that likely resulted from the influence of several important controlling factors such as the isotopic composition of ingested water, the consistent fractionation of oxygen isotopes between body water and tooth enamel, and the animal's metabolism (e.g.,55,56) or from the nonsimultaneous occurrence of fossils that represented a different age through the stratigraphic section. The pairwise Mann–whitney U test indicates that there are almost no statistically significant differences in median δ18O values between two TLR mammal taxa (P > 0.05), except for wild boars (Supplementary Table S5). The wild boars displayed lower δ18O values (median: − 8.9‰, range: − 11.2‰ to − 5.1‰, n = 14), compared to other mammal taxa within the same locality (P < 0.05). It is possible that these suids fed on more 18O- depleted foodstuffs (such as fallen fruits, roots, and tubers) on the open forest/woodland ground surfaces57,58.

Serial sampling isotope analysis

As large bovid molars gradually mineralize on average with the enamel growth rate of approximate 40–50 mm (in height) per year59–61, we analyzed five high-crowned molars of large bovids (Bos gaurus (n = 3), Bos javanicus (n = 1), and Bos sp. (n = 1)) from different stratigraphic layers of TLR to demonstrate seasonal patterns in diet and precipitation through the late Pleistocene (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 4.

Sequential tooth enamel δ13C (blue circle) and δ18O (orange square) records along the crown height of large bovids. TLR (Tham Lod Rockshelter) and CEJ (Cemento-enamel junction).

Our serially analyzed isotope samples of large bovid molars showed little δ13C variation of 1.2‰ (from − 0.4‰ to + 0.8‰) for TLR-A3697, 0.9‰ (from + 0.5‰ to + 1.4‰) for TLR-A1677, 1.0‰ (from + 1.7‰ to + 2.7‰) for TLR-A1291, 3.0‰ (from − 2.1‰ to + 0.9‰) for TLR-A1207, and 0.8‰ (from + 1.1‰ to + 1.9‰) for TLR-A920, all of which indicate grazing habits on the same types of food items (pure C4 plants) throughout the course of almost 1 year during the terminal Pleistocene (Fig. 4).

The serial δ18O values of large bovids yielded a small fluctuation of 2.2‰ (from − 8.8‰ to − 6.6‰) for TLR-A3697, 2.4‰ (from − 6.5‰ to − 4.1‰) for TLR-A1677, 2.7‰ (from − 6.7‰ to − 4.0‰) for TLR-A1291, 2.1‰ (from − 8.9‰ to − 6.8‰) for TLR-A1207, and 2.4‰ (from − 4.4‰ to − 6.8‰) for TLR-A920. All the serially analyzed samples showed little seasonal variation in precipitation over several months to years through the terminal Pleistocene (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Expansion of savanna corridor and environmental/climatic impacts on hunter-gatherer settlement

Our carbon isotope results of the extensive faunal baseline implied the expansion of a forest-grassland mosaic ecosystem into the high-altitude or mountainous area of Pang Mapha, up to about 600 m above present-day sea level, where the mixture of semi-evergreen and dry dipterocarp forests is typical of this elevation today14. Many types of savanna formations are still present today across MSEA, but they are mostly patchy and fragmented62. This study suggests that mixed tropical forest/grasslands were more widespread and connected in MSEA during the terminal Pleistocene, as many grazing species relied exclusively on C4 grasses (Fig. 5 and see4,10 for more detailed information and other available proxy sources). As supported by similar isotope compositions of a contemporaneous mammal fauna from the slightly higher-latitude cave of Tam Hay Marklot in Laos36, we purport to document the possible extension of a latitudinal limit of the savanna corridor farther north than previously recorded during the LGM (Fig. 1). Despite the hunter-gatherers having faced with the landscape of high mountain ranges in the northern part of MSEA during the process of dispersal, such a savanna corridor widely stretching from northern Thailand and Laos to either Central Sundaland or Western Java would have served as a convenient route for early human and large mammal migrations out of MSEA, across the Sunda Shelf, and into ISEA during the LGM.

Figure 5.

Distribution of enamel δ13C values of mammalian assemblages (herbivores (blue), omnivores (orange), and carnivores (yellow)) between Tham Lod Rockshelter (terminal Pleistocene, n = 195) and mainland Southeast Asia (modern samples, n = 121). Stable carbon isotope datasets for modern mainland Southeast Asian mammals were obtained from the existing literature10,54,63,64. A Suess effect δ13C correction is applied for samples of modern mammals that died after ad 195034,65. The samples of carnivorous mammals were adjusted by + 1.3‰42,43. All enamel δ13C values plotted here are given in Supplementary Tables S4 and S7.

Although no significant shift in δ13C and δ18O values among mammalian individuals through the stratigraphic section of TLR (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3) and no major seasonal variation in dietary and climatic patterns acquired from the intra-tooth profiles of large bovid crowns over the year (Fig. 4) are discernible through this study, other related information and proxies have provided direct evidence for the regional climate changes through the period of late Pleistocene glaciation. Sequential δ18O records of analyzed freshwater bivalves collected from TLR implied wetter and relatively unstable climatic conditions from 35 to 20 ka and drier conditions from 20 to 11.5 ka (with an aridity peak around 15.6 ka)28 (Fig. 6). Speleothem δ18O records obtained from nearby regions (western Thailand, Myanmar, and South China) indicated a dramatic shift in precipitation to the wetter climate condition starting around 16 ka (Heinrich event 1) and at the end of the Pleistocene (Younger Dryas)66–68 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Trends of ecosystems over a time period of the terminal Pleistocene (34–12 ka) based on percentages of C3 browsers (forests/woodlands), C3–C4 mixed feeders (intermediate landscapes between closed and open canopies), and C4 grazers (grasslands) through the stratigraphic sequence of Tham Rod Rockshelter, in comparison with freshwater bivalve δ18O data (black dot) collected from the same stratigraphic section (west profile)28, with speleothem δ18O records data using 1000-year averages from mainland Southeast Asia including eastern coastal Bay of Bengal and Mawmluh (red line), central Myanmar (pink line), and southeastern Yunnan (purple line)66–68, and with sea-level fluctuations (sky blue)69. Available dietary information for all mammalian taxa from TLR was distinguished based on the carbon isotope data with the cut-off δ13C values lower than − 10‰ for a pure C3 diet, between − 10‰ and − 2‰ for a mixed C3/C4 diet, and higher than − 2‰ for a pure C4 diet34,40,41. High-resolution chronological data of the TLR sequence follow radiobarbon dates on freshwater bivalves collected from each stratigraphic layer28.

As demonstrated by our carbon isotope data through the stratigraphic sequence of TLR, it seems unlikely that the Bølling–Allerød event affected human subsistence patterns at that period due to the persistence of heterogeneous environments with the availability of potential needed resources (Fig. 6). Although the homogeneity of environments has been discernible through some stratigraphic layers (i.e. layers 9, 11, 13, and 30) of TLR (Fig. 6), this was most likely due to the effects of analyzing an isotope dataset with small sample sizes. In relation to sea-level rise during the terminal Pleistocene-Holocene boundary69, the broad expansion of tropical rainforests or the replacement of forest/grassland mosaics by closed forest environments has also been documented elsewhere based on several studies and proxy records in SEA70. One human sample (specimen no. 611) collected at the layer 3 of TLR (dated around 12 ka) showed alongside a shift in δ13C towards higher reliance on C3-based resources in a more closed habitat during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, this study does not permit to make inferences on the timing of an ecological shift among hunter-gatherers in the area based on the proposal of one human isotope sample, which is likely to be biased. Overall, our carbon isotope data advocate that highland Pang Mapha provided an unprecedentedly optimal niche with broad-spectrum resources for the survival of hunter-gatherers during the terminal Pleistocene.

Hunter-gatherer mobility and adaptation during the late Pleistocene

Along the major routes of human migration from Africa to Australia and across SEA, recent studies have shown that tropical rainforests, previously thought as an unfavorable niche for the early human occupation71, have successfully been exploited by some hunter-gatherers for at least 45 ka (e.g., Africa72–74, Sri Lanka75–78, South China12,79, Vietnam80–82, Borneo83–85, Sumatra86,87, Java88,89, Timor90, Papua91, and New Guinea92–94). Despite the seemingly specialized occupation of coastal resources by other human populations in ISEA within Wallacea, stable isotope compositions of human and faunal tooth enamel in Alor suggested the possible availability of C4 resources used by late Pleistocene small mammals and hunter-gatherer populations (40–21 ka)90. All the evidence has suggested so far that more specialized hunting of arboreal and semi-arboreal mammals and the occupation of tropical rainforest habitats have commonly been favored among the late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer populations from these aforementioned regions. Unlike the long-established rainforest occupation by those late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers, our isotopic data provide direct evidence for human reliance on the different types of habitats (dated around 19–12 ka) in MSEA.

Based on available zooarchaeological information on the taxonomic diversity, species abundance, and mortality profiles of successive faunal assemblages from TLR, it has been suggested that hunter-gatherers in the area adopted a generalized and mixed subsistence strategy30,31. Studies of lithic assemblages have shown that classical sumatralith forms such as flakes and radial cores made from metaquartzites or sandstones were found from TLR, while microliths indicative of specialized rainforest hunting by Homo sapiens, as discovered in the archaeological sites of Sri Lanka about ~ 45,000 years ago78,95, were absent in the area26,27,29. The analysis of ecological models applied to flaked stone artefacts in TLR have suggested that proximity to resources and climate change were important factors influencing Hoabinhian technology26,29. In addition, the stable isotope data obtained in the present study allow us to evaluate directly the degree of early modern human reliance on a broad spectrum of resources and to refine the relationship between the lithic assemblages and prevailing open environments in TLR. Environmental heterogeneity in highland Pang Mapha allowed Homo sapiens to have more opportunistic foraging on various types of preys and more available C3- and C4-based resources to exploit during the terminal Pleistocene. The population of late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers in Pang Mapha might have selected a settlement option at the edge of open forests where they could take advantage to exploit both closed and open canopy resources, not a particular area in one extreme direction of environmental ranges. Compared to the timing of microlithic records in South Asia, our study reinforces the late occurrence of the proliferation of microliths in highland MSEA. The high environmental heterogeneity resulted in low ecological stress in forcing and shaping behavioural adaptations among the late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers, allowing the persistence of similar subsistence patterns and stone artefact technology in the area for at least 20,000 years.

As it is visible in the settlement of highland Northwest Thailand by early modern humans during the late Pleistocene, they have ventured into high-altitude mountains where the savanna ecosystem was present. Although the TLR hunter-gatherers had the mixed grassland and woodland adaptations comparable to other earlier hominins such as Homo erectus and Homo florensiensis in ISEA (e.g.,96,97), the degree and direction of ecological reliance between Homo sapiens and other hominin species on the broad spectrum of resources and environments might be questioned and require future studies. However, our findings stand in striking contrast to the specialized rainforest occupation among other contemporaneous hunter-gatherers in MSEA’s neighboring continents/regions. Our isotopic evidence not only suggests the asynchronous occurrence of specialized rainforest occupations among the hunter-gatherer populations in MSEA, but also documents diverse late Pleistocene human adaptations during the process of dispersal towards Wallacea and Sahul.

Methods

Sample collection and design

We analyzed a total of 139 bulk tooth enamel samples of humans and non-human mammals from the late Pleistocene archaeological sites of Tham Lod Rockshelter in highland Pang Mapha. Five high-crowned teeth of large bovids from TLR (45 samples) were selected for serial sampling. All teeth were collected along each well-dated layer from one stratigraphic side of the wall (west profile) in the Area 1 of TLR, in order to ensure the vertical placement of samples (Fig. 2). Sixteen samples of dentine and five samples of soil carbonates were additionally analyzed for isotopic comparisons (see Supplementary Information 2, Supplementary Table S8, and Supplementary Fig. S4 for isotope datasets and interpretations). All available dates and geological information for the site are given in Supplementary Information 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Stable carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of carbonates

For preliminary measurements in the study, we performed a CNS elemental analysis to test the possibility of collagen preservation in bone and dentine samples from Tham Lod Rockshelter (Supplementary Table S3). The CNS analysis was conducted at the Laboratory for Soil Science and Geoecology (University of Tübingen) using a Vario EL III elemental analyzer. As is the case for the site studied here, the bone and dentine collagen has highly been degraded over most of the stratigraphic layers and is nearly impossible to be extracted. Therefore, the isotopic data were retrieved from the bioapatite carbonate of tooth enamel.

Bulk enamel powder was sampled along the whole length of a tooth crown in order to obtain average isotopic signals over the time period of dental growth, while serial sampling was taken along a non-occlusal surface parallel to the growth axis and across its entire length (lengthwise from the top to the bottom of tooth crowns) on the labial side of lower molars. The isotopic pretreatment and measurements of samples were performed at the Department of Geosciences, University of Tübingen, Germany (see Supplementary Information 3 for more detailed information on the isotopic pretreatment and protocols). Stable carbon and oxygen isotopic values are expressed as the following standard delta (δ)–notation: X = [(Rsample/Rstandard) − 1]*1000, where X stands for 13C and 18O values and R is referred to 13C/12C or 18O/16O, respectively. The recorded delta values follow the international reference standards, “Vienna PeeDee Belemnite” (VPDB) for the carbon and oxygen. δ18O values relative to “Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water” (VSMOW) are also given. The carbonate content (CaCO3%) was calculated using the ratio between amount of CO2 released by the reaction, as detected from the peak intensity for mass 44 and the weight of pure carbonate used as a standard, with an analytical error of 0.3%, based on the multiple analysis of reference enamel samples.

Statistical analysis

Using the Shapiro–Wilk test, our samples with unequal variances do not correspond to a normal distribution. In the case for which at least five samples are available, δ13C and δ18O values were statistically tested for examining a significant difference among our analyzed enamel dataset. We thus performed non-parametric tests to analyze differences in median δ13C and δ18O values among our isotopic samples within the locality (Kruskal–Wallis test) and between the species (Mann–Whitney U-test) (Supplementary Table S5). Significant differences are statistically attained when p-values are equal to or less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using the software PAST version 498.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Athiwat Wattanapituksakul, Siriluck Kantasri, Wokanya Na Nongkhai, and Chonchanok Samrit for providing helpful information on archaeological sites in Pang Mapha and for all facilities during our sample collection process, Suravech Suteethorn for help with sample transportation, Santi Pailoplee for help with map illustration, and Peter Tung for help with carbonate isotope analyses. This research was funded by Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Georg Forster Research Fellowship, to K.S.). The archaeological excavations in Pang Mapha under “the Prehistoric Population and Cultural Dynamics in Highland Pang Mapha Project” were supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI, Grant No. RTA6080001, to R.S.), which made all the material available for this study.

Author contributions

K.S., R.S., and H.B. conceived the research project. R.S. and K.C. acquired and gathered data. K.S. and H.B. performed laboratory analysis, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. K.S. was a principal investigator of the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-96260-4.

References

- 1.Roberts P, Stewart BA. Defining the ‘generalist specialist’ niche for Pleistocene Homo sapiens. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018;2:542–550. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaney LR. A synopsis of climatic and vegetational change in Southeast Asia. Clim. Change. 1991;19:53–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00142213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morley RJ. Origin and Evolution of Tropical Rain Forests. Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird MI, Taylor D, Hunt C. Palaeoenvironments of insular Southeast Asia during the last Glacial Period: a savanna corridor in Sundaland? Quat. Sci. Rev. 2005;24:2228–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wurster CM, Rifai H, Zhou B, Haig J, Bird MI. Savanna in equatorial Borneo during the late Pleistocene. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:6392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42670-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wurster CM, Bird MI. Barriers and bridges: early human dispersals in equatorial SE Asia. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2016;411:235–250. doi: 10.1144/SP411.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaim Y. Geological evidence for the earliest appearance of hominins in Indonesia. In: Fleagle JG, Shea JJ, Grine FE, Baden AL, Leakey RE, editors. Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia. Springer; 2010. pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon CH, Morley RJ, Bush ABG. The current refugial rainforests of Sundaland are unrepresentative of their biogeographic past and highly vulnerable to disturbance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11188–11193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809865106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raes N, et al. Historical distribution of Sundaland’s Dipterocarp rainforests at Quaternary glacial maxima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16790–16795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403053111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suraprasit K, Jongautchariyakul S, Yamee C, Pothichaiya C, Bocherens H. New fossil and isotope evidence for the Pleistocene zoogeographic transition and hypothesized savanna corridor in peninsular Thailand. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019;221:1055861. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pookajorn S. Human activities and environmental changes during the late pleistocene to middle holocene in Southern Thailand and Southeast Asia. In: Straus LG, Eriksen BV, Erlandson JM, Yesner DR, editors. Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene—Holocene Transition, Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Springer; 1996. pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schepartz LA, Miller-Antonio S, Bakken DA. Upland resources and the early palaeolithic occupation of Southern China, Vietnam, Laos Thailand and Burma. World Archaeol. 2000;32:1–13. doi: 10.1080/004382400409862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mudar K, Anderson D. New evidence for Southeast Asian pleistocene foraging economies: faunal remains from the early levels of Lang Rongrien Rockshelter, Krabi, Thailand. Asian Perspect. 2007;46:298–334. doi: 10.1353/asi.2007.0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoocongdej R. Late Pleistocene activities at the Tham Lod rockshelter in Highland Pang Mapha, Mae Hong Son province, Norhwestern Thailand. In: Bacus E, Glover I, Pigott V, editors. Uncovering Southeast Asia's Past. NUS Press; 2006. pp. 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoocongdej, R. et al. Final report of Highland Archaeology Project in Pang Mapha District, Mae Hong Son Province Phase 2, Vol. 2 (Thailand Research Fund, 2007).

- 16.Demeter F, et al. Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos) by 46 ka. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:14375–14380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208104109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demeter F, et al. Early modern humans and morphological variation in Southeast Asia: fossil evidence from Tam Pa Ling. Laos. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0121193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viet N. First archaeological evidence of symbolic activities from the Pleistocene of Vietnam. In: Kaifu Y, editor. Emergence and Diversity of Human Behavior Paleolithic Asia. Texas A&M University Press; 2015. pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higham CF, Thosarat R. An early hunter-gatherer site at Ban Non Wat, Northeast Thailand. J. Indo. Pacif. Archaeol. 2019;43:93–96. doi: 10.7152/jipa.v43i0.15413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorman CF. Excavations at Spirit Cave, North Thailand: Some Interim Interpretations. Asian Perspect. 1970;13:79–107. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tayles N, Halcrow SE, Sayavongkhamdy T, Souksavatdy V. A prehistoric flexed human burial from Pha Phen, Middle Mekong Valley, Laos: its context in Southeast Asia. Anthropol. Sci. 2015;123:1–12. doi: 10.1537/ase.141013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad C, Higham C, Eda M, Marwick B. Palaeoecology and forager subsistence strategies during the Pleistocene—Holocene transition: A reinvestigation of the zooarchaeological assemblage from Spirit Cave, Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand. Asian Perspect. 2016;5:2–27. doi: 10.1353/asi.2016.0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeitoun VD, et al. Discovery of an outstanding Hoabinhian site from the Late Pleistocene at Doi Pha Kan (Lampang province, northern Thailand) Archaeol. Res. Asia. 2019;18:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ara.2019.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoocongdej R. Forager mobility organization in seasonal tropical environments of western Thailand. World Archaeol. 2000;32:14–40. doi: 10.1080/004382400409871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forestier H, et al. The Hoabinhian from Laang Spean Cave in its stratigraphic, chronological, typo-technological and environmental context (Cambodia, Battambang province) J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2015;3:194–206. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chitkament T, Gaillard C, Shoocongdej R. Tham Lod rockshelter (Pang Mapha district, north-western Thailand): Evolution of the lithic assemblages during the late Pleistocene. Quat. Int. 2016;416:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marwick B. The Hoabinhian of Southeast Asia and its relationship to regional Pleistocene lithic technologies. In: Robinson E, Sellet F, editors. Lithic Technological Organization and Paleoenvironmental Change Global and Diachronic Perspectives. Springer; 2018. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marwick B, Gagan MK. Late Pleistocene monsoon variability in northwest Thailand: an oxygen isotope sequence from the bivalve Margaritanopsis laosensis excavated in Mae Hong Son province. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2011;30:3088–3098. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marwick B. Multiple Optima in Hoabinhian flaked stone artefact palaeoeconomics and palaeoecology at two archaeological sites in Northwest Thailand. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2013;32:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2013.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wattanapituksakul A, Filoux A, Amphansri A, Tumpeesuwan S. Late Pleistocene Caprinae assemblages of Tham Lod Rockshelter (Mae Hong Son Province, Northwest Thailand) Quat. Int. 2018;493:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoocongdej R, Wattanapituksakul A. Faunal assemblages and demography during the Late Pleistocene (MIS 2–1) to Early Holocene in Highland Pang Mapha, Northwest Thailand. Quat. Int. 2020;563:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2020.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1978;42:495–506. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Der Merwe NJ, Vogel JC. 13C Content of human collagen as a measure of prehistoric diet in woodland North America. Nature. 1978;276:815–816. doi: 10.1038/276815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerling TE, Harris JM. Carbon isotope fractionation between diet and bioapatite in ungulate mammals and implications for ecological and paleoecological studies. Oecologia. 1999;120:347–363. doi: 10.1007/s004420050868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerling TE, Hart JA, Hart TB. Stable isotope ecology in the Ituri Forest. Oecologia. 2004;138:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourgon N, et al. Zinc isotopes in Late Pleistocene fossil teeth from a Southeast Asian cave setting preserve paleodietary information. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:4675–4681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911744117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Klinken GJ. Bone Collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999;26:687–695. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1998.0385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pestle WJ, Colvard M. Bone collagen preservation in the tropics: a case study from ancient Puerto Rico. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012;39:2079–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2012.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ecker M, et al. Middle Pleistocene ecology and Neanderthal subsistence: Insights from stable isotope analyses in Payre (Ardèche, southeastern France) J. Hum. Evol. 2013;65:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohn M, Cerling TE. Stable isotope compositions of biological apatite. In: Kohn M, Rakovan J, Hughes J, editors. Phosphates—Geochemical Geobiological and Materials Importance Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. Mineralogical Society of America; 2002. pp. 455–488. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biasatti D, Wang Y, Gao F, Xu Y, Flynn L. Paleoecologies and paleoclimates of late cenozoic mammals from Southwest China: evidence from stable carbon and oxygen isotopes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012;44:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jseaes.2011.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clementz MT, Fox-Dobbs K, Wheatley P-V, Koch PL, Doak DF. Revisiting old bones: coupled carbon isotope analysis of bioapatite and collagen as an ecological and palaeoecological tool. Geol. J. 2009;44:605–620. doi: 10.1002/gj.1173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Domingo MS, Domingo L, Badgley C, Sanisidro O, Morales J. Resource partitioning among top predators in a Miocene food web. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2013;280:20122138. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Codron D, Clauss M, Codron J, Tütken T. Within trophic level shifts in collagen–carbonate stable carbon isotope spacing are propagated by diet and digestive physiology in large mammal herbivores. Ecol. Evol. 2018;8:3983–3995. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tejada-Lara JV, et al. Body mass predicts isotope enrichment in herbivorous mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2018;285:20181020. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cerling TE, et al. Stable isotope-based diet reconstructions of Turkana Basin hominins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:10501–10506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222568110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayliffe LK, Chivas AR. Oxygen isotope composition of the bone phosphate of Australian kangaroos: potential as a palaeoenvironmental recorder. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1990;54:2603–2609. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(90)90246-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levin NE, Cerling TE, Passey BH, Harris JM, Ehleringer JR. A stable isotope aridity index for terrestrial environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11201–11205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604719103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bocherens H, Koch P, Mariotti A, Geraads D, Jaeger J-J. Isotopic biogeochemistry (13C, 18O) of mammalian enamel from African Pleistocene hominoid sites. Palaios. 1996;11:306–308. doi: 10.2307/3515241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hambali K, Ismail A, Md-Zain BM, Amir A, Karim FA. Diet of long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) at the entrance of Kuala Selangor Nature Park (anthropogenic habitat): food selection that leads to human-macaque conflict. Acta Biol. Malay. 2014;3:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nila S, Suryobroto B, Widayati KA. Dietary variation of long tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in Telaga Warna, Bogor, West Java. HAYATI J. Biosci. 2014;21:8–14. doi: 10.4308/hjb.21.1.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lekagul B, McNeely JA. Mammals of Thailand: Association for the Conservation of Wildlife. Kurusapa Ladproa Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suraprasit K, Bocherens H, Chaimanee Y, Panha S, Jaeger J-J. Late Middle Pleistocene ecology and climate in Northeastern Thailand inferred from the stable isotope analysis of Khok Sung herbivore tooth enamel and the land mammal cenogram. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018;193:24–42. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suraprasit K, et al. Long-term isotope evidence on the diet and habitat breadth of pleistocene to holocene caprines in Thailand: implications for the extirpation and conservation of Himalayan Gorals. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020;8:67. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kohn MJ. Predicting animal δ18O: Accounting for diet and physiological adaptation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1996;60:4811–4829. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00240-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kohn MJ, Schoeninger MJ, Valley JW. Herbivore tooth oxygen isotope compositions: effects of diet and physiology. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1996;60:3889–3896. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(96)00248-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunbar J, Wilson T. Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in fruits and vegetable juices. Plant Physiol. 1983;72:725–727. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.3.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yakir D. Variations in the natural abundances of oxygen-18 and deuterium in plant carbohydrates. Plant Cell Environ. 1992;15:1005–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1992.tb01652.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fricke HC, O'Neil JR. Inter- and intra-tooth variation in the oxygen isotope composition of mammalian tooth enamel phosphate: implications for palaeoclimatological and palaeobiological research. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1996;126:91–99. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(96)00072-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fricke HC, Clyde WC, O'Neil JR. Intra-tooth variations in δ18O (PO4) of mammalian tooth enamel as a record of seasonal variations in continental climate variables. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta. 1998;62:1839–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00114-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balasse M, Ambrose SH, Smith AB, Price TD. The seasonal mobility model for prehistoric herders in the south-western Cape of South Africa assessed by isotopic analysis of sheep tooth enamel. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2002;29:917–932. doi: 10.1006/jasc.2001.0787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ratnam J, Tomlinson KW, Rasquinha DN, Sankaran M. Savannahs of Asia: antiquity, biogeography, and an uncertain future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016;371:2015305. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pushkina D, Bocherens H, Chaimanee Y, Jaeger J-J. Stable carbon isotope reconstructions of diet and paleoenvironment from the late middle Pleistocene Snake Cave in Northeastern Thailand. Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s00114-009-0642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Louys J, Roberts P. Environmental drivers of megafauna and hominin extinction in Southeast Asia. Nature. 2020;586:402–406. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2810-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Passey BH, et al. Carbon isotope fractionation between diet, breath CO2, and bioapatite in different mammals. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2005;32:1459–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2005.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dutt S, et al. Abrupt changes in Indian summer monsoon strength during 33,800 to 5500 years B.P. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015;42:5526–5532. doi: 10.1002/2015GL064015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ronay ER, Breitenbach SFM, Oster JL. Sensitivity of speleothem records in the Indian Summer Monsoon region to dry season infiltration. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5091. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu G, et al. On the glacial-interglacial variability of the Asian monsoon in speleothem δ18O records. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:8eaay8189. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay8189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lambeck K, Rouby H, Purcell A, Sun Y, Sambridge M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15296–15303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411762111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rabett RJ. Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: hominin dispersal and behaviour during the late quaternary. Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bailey RC, et al. Hunting and gathering in tropical rain forest: Is it possible? Am. Anthropol. 1989;91:59–82. doi: 10.1525/aa.1989.91.1.02a00040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mercader J. Forest people: the role of African rainforests in human evolution and dispersal. Evol. Anthropol. 2002;11:117–124. doi: 10.1002/evan.10022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mercader J. Under the Canopy: The Archaeology of Tropical Rainforests. Rutgers University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mercader J. Foragers of the Congo: the early settlement of the Ituri forest. In: Mercader J, editor. Under the Canopy: The Archeology of Tropical Rain Forests. London: Rutgers University Press; 2003. pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perera N, et al. People of the ancient rainforest: Late Pleistocene foragers at the Batadomba-lena rockshelter, Sri Lanka. J. Hum. Evol. 2011;61:254–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roberts P, et al. Direct evidence for human reliance on rainforest resources in late Pleistocene Sri Lanka. Science. 2015;347:1246–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roberts P, et al. Fruits of the forest: human stable isotope ecology and rainforest adaptations in Late Pleistocene and Holocene (~36 to 3 ka) Sri Lanka. J. Hum. Evol. 2017;106:102–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wedage O, et al. Specialized rainforest hunting by Homo sapiens ~45,000 years ago. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:739. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08623-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ji X, et al. The oldest Hoabinhian technocomplex in Asia (43.5 ka) at Xiaodong rockshelter, Yunnan Province, southwest China. Quat. Int. 2016;400:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olsen JW, Ciochon RL. A review of evidence for postulated Middle Pleistocene occupations in Viet Nam. J. Hum. Evol. 1990;19:761–788. doi: 10.1016/0047-2484(90)90020-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rabett R, et al. The Tràng An Project: Late-to-Post-Pleistocene Settlement of the Lower Song Hong Valley, North Vietnam. J. R. Asiat. Soc. 2009;19:83–109. doi: 10.1017/S1356186308009061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rabett R, et al. Tropical limestone forest resilience and late Pleistocene foraging during MIS-2 in the Tràng An massif, Vietnam. Quat. Int. 2017;448:62–81. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2016.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barker G, et al. The ‘Human Revolution’ in lowland tropical Southeast Asia: the antiquity and behavior of anatomically modern humans at Niah Cave (Sarawak, Borneo) J. Hum. Evol. 2007;52:243–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Piper P, Rabett R. Hunting in a tropical rainforest: evidence from the terminal Pleistocene at Lobang Hangus, Niah Caves, Sarawak. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2009;19:551–565. doi: 10.1002/oa.1046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hunt CO, Gilbertson DD, Rushworth G. A 50,000-year record of late Pleistocene tropical vegetation and human impact in lowland Borneo. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2012;37:61–80. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Vos J. The Pongo faunas from Java and Sumatra and their significance for biostratigraphical and paleoecological interpretations. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. B. 1983;86:417–425. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Westaway KE. An early modern human presence in Sumatra 73000–63000 years ago. Nature. 2017;548:322–325. doi: 10.1038/nature23452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Storm P, et al. Late Pleistocene Homo Sapiens in a tropical rainforest Fauna in East Java. J. Hum. Evol. 2005;49:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Storm P, de Vos J. Rediscovery of the late Pleistocene Punung Hominin Sites and the Discovery of a New Site Gunung Dawung in East Java. Senck. Leth. 2006;86:271–281. doi: 10.1007/BF03043494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roberts P, et al. Isotopic evidence for initial coastal colonization and subsequent diversification in the human occupation of Wallacea. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2068. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15969-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pasveer JM, Clarke SJ, Miller GH. Late Pleistocene human occupation of inland rainforest, Bird’s Head, Papua. Archaeol. Oceania. 2002;37:92–95. doi: 10.1002/j.1834-4453.2002.tb00510.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Summerhayes GR, et al. Human adaptation and plant use in highland New Guinea 49,000 to 44,000 Years Ago. Science. 2010;330:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1193130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Summerhayes GR, Field JH, Shaw B, Gaffney D. The archaeology of forest exploitation and change in the tropics during the Pleistocene: the case of Northern Sahul (Pleistocene New Guinea) Quat. Int. 2017;448:14–30. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2016.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roberts P, Gaffney D, Lee-Thorp JA, Summerhayes GR. Persistent tropical foraging in the highlands of terminal Pleistocene/Holocene New Guinea. Nature Ecol. Evol. 2017;1:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wedage O, et al. Microliths in the South Asian rainforest ~45–4 ka: New insights from Fa-Hien Lena Cave, Sri Lanka. PLoS ONE. 2019 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bettis EA, et al. Way out of Africa: early Pleistocene paleoenvironments inhabited by Homo erectus in Sangiran, Java. J. Hum. Evol. 2009;56:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brumm A, et al. Age and context of the oldest known hominin fossils from Flores. Nature. 2016;534:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature17663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.