Abstract

Bone marrow failure syndromes (BMF) are a group of conditions characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis frequently associated with extra-hematopoietic phenotypes and variable risk of progression to myeloid malignancies. They can be acquired or inherited and mediated by either cell extrinsic factors or cell intrinsic impairment of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function. The pathophysiology includes immune-mediated attack (e.g., acquired BMFs) or germline defects in in DNA damage repair machinery, telomeres maintenance or ribosomes biogenesis. (e.g., inherited BMF). Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) that frequently accompanies BMF may provide a mechanism of improved HSC fitness through the evasion of extracellular pressure or somatic reversion of germline defects. The mechanism for the CH selective advantage differs depending on the condition in which it occurs. However, this adaptation mechanism, particularly when involving putative oncogenes or tumor suppressors, may lead to increased risk of myeloid malignancies. Surveillance and early detection of leukemogenic clones may lead to timely implementation of curative therapies and improved survival.

Keywords: clonal hematopoiesis, bone marrow failure, somatic reversion, leukemic transformation

1. Introduction

Bone marrow failure syndromes (BMFs) are a group of diseases characterized by the inability of the bone marrow to produce one or multiple elements of the blood. Considering this broad definition, BMFs encompass a plethora of conditions, both acquired and congenital with various pathogenic mechanisms [1]. Despite distinct pathobiology, BMFs are uniformly associated with intrinsic or extrinsic stress imposed on hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) [2]. Acquired BMFs such as aplastic anemia or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria are frequently associated with HSC-extrinsic, immune attack [3–5]. Conversely, HSC-intrinsic stress occurs in the context of germline genetic alterations that disturb hematopoietic output, a key feature of inherited BMF (iBMF) [6].

In fact, somatic mutations as well as structural and numerical chromosomal abnormalities have been described in many inherited and acquired BMFs. Somatic genetic alterations may confer an adaptive mechanism and improve HSC fitness leading to emergence of hematopoietic clones. Such expansion of the hematopoietic progeny arising from a single HSC is called clonal hematopoiesis (CH). Since some of the genetic alterations affect genes frequently involved in MDS and AML, thus the presence of CH may be predictive of malignant transformation. Here, we review the possible mechanisms leading to CH in acquired and inherited BMFs and discuss their clinical implications.

2. Definition of clonal hematopoiesis

The human hematopoietic system is responsible for the production of trillions of cells each day [7]. This is achieved through a highly coordinated process of self-renewal, differentiation and proliferation of HSCs and progenitor cells. Since it is estimated that 10,000–200,000 HSCs are present in the human body, healthy and undisturbed hematopoiesis is always polyclonal. Any sustained dominance of a hematopoietic clone arising from a single HSC, over the rest of hematopoietic cells is known as CH. Even though this condition is a sine qua non for all hematologic malignancies, it may be also present in otherwise healthy individuals without an apparent hematological condition [8]. Over the last decade CH has been found to be associated with a variety of hematologic conditions, thus numerous new definitions and acronyms containing CH have been introduced resulting in somewhat confusing nomenclature, particularly for the practicing hematologist. Below we provide the acronyms and definitions of various, clinically important CH conditions.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), also known as age-related clonal hematopoiesis (ARCH), denotes the presence of clonal expansion of hematopoietic clone(s) carrying one or more somatic mutations in genes associated with myeloid malignancies in individuals with otherwise unremarkable hemograms. Additionally, the mutations must be present in more than 2% of the DNA molecules (also known as variant allele frequency, VAF), although the exact VAF cut-off for the definition of CHIP is rather controversial and the clinical implications seem to vary depending not only on the mutated genes but also the size of the clone [8–10].

Clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS), is defined as the presence of CH in patients with persistent uni- or multilineage cytopenia in the absence of alternative explanations for cytopenias [10]. It should be emphasized that CCUS is an entity where the cytopenias must be solely attributed to the underlying clonal process [8]. Hence, this condition likely represents early stages of myeloid neoplasm. In fact, over 90% of CCUS patients with more than two mutations will eventually fulfill the diagnostic criteria for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [11]. Therefore, the presence of DNMT3A mutation at the VAF of 2% (suggesting that 4% of peripheral blood nucleated cells are clonal) and anemia would not be sufficient to diagnose CCUS and alternative explanations for anemia ought to be considered. Idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined potential (ICUS) is defined as the presence of persistent cytopenia in one or multiple lineages, unexplained (after extensive investigation) by other diseases and without the presence of clonality [12].

We advocate that the term CH be used for any condition involving clonality that does not meet the criteria for aforementioned states.

3. Mechanism of CH

CH usually arises as sequelae of multiple and frequently not mutually exclusive processes. The relative clonal dominance may be simply a stochastic process such as HSC pool attrition with aging on one hand, or the increased stem cell fitness on the other. Even though the exact mechanism of clonal expansion is not entirely clear, it is now widely accepted that random somatic genetic alteration, either single base substitutions and small indels or large chromosomal alterations result in positive selection and competitive advantage of mutated clones [13]. This nearly imperceptible increase in HSC fitness may accumulate over years or decades resulting in single clone’s dominance over unmutated competitors over time. This process may be indolent (as in ARCH) or accelerated by extra- and intracellular stressors. The former is frequent in acquired BMFs such as aplastic anemia (AA) or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), where cytopenias are the consequence of immune-mediated attack on HSCs [4,5] or in the case of chemotherapy treatment where cytopenias are the consequences of the cytotoxicity of the agents used [14–16]. Intrinsic stress can be observed in inherited BMFs (iBMF) with various mechanisms leading to impaired hematopoiesis [6].

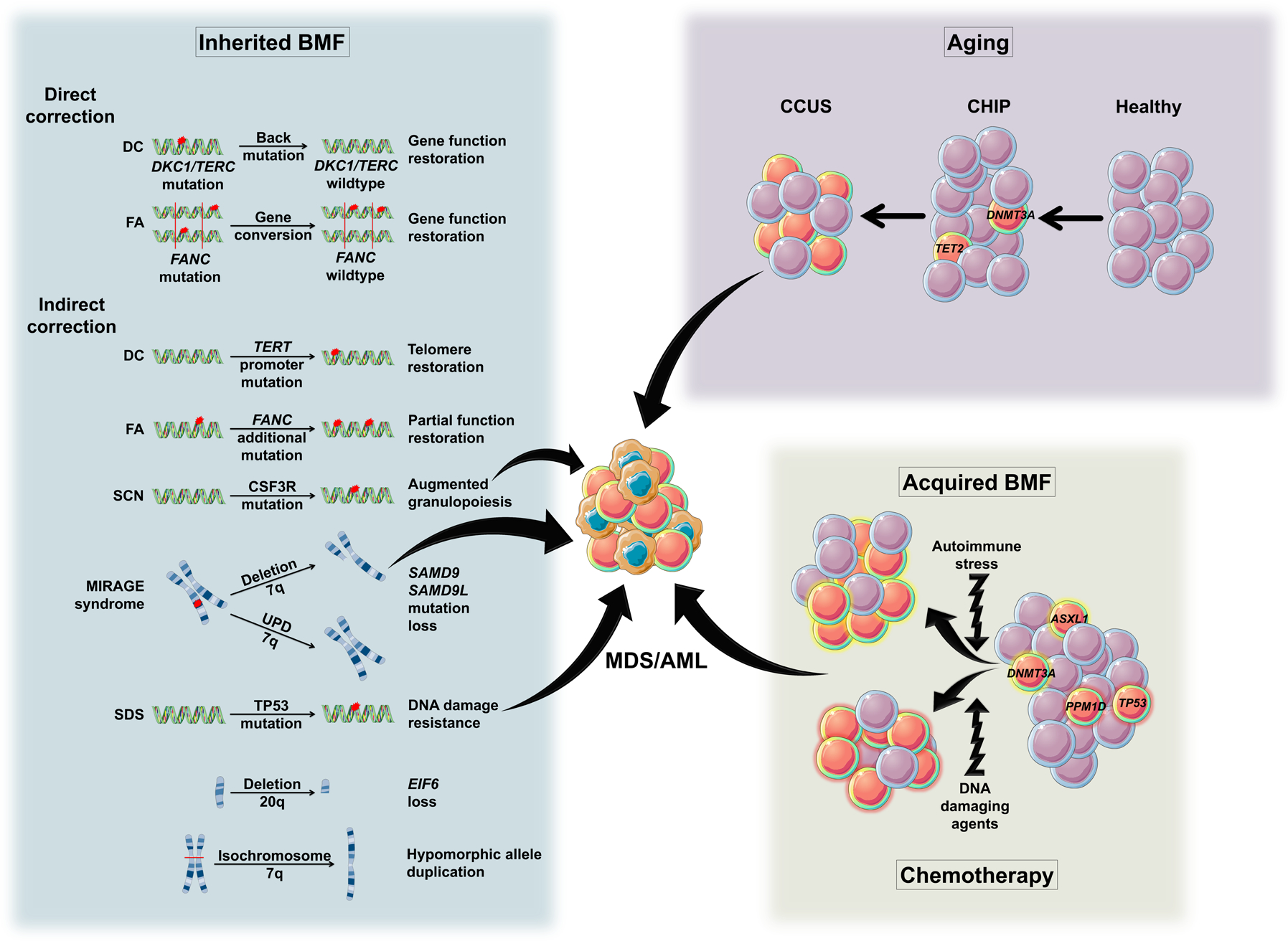

Thus, the selection of clones with somatic genetic alteration leading to improved stem cell fitness is highly context dependent and dictated mostly by the nature of the underlying selective pressure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of CH as a response to HSC stress. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; CHIP. clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential; CCUS, clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AA, aplastic anemia; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; DC, dyskeratosis congenita; FA, Fanconi anemia; SCN, Severe congenital neutropenia; SDS, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome; UPD, uniparental disomy. The arrows represent the risk of leukemic transformation.

4. Clonal hematopoiesis in aging

The rate of somatic mutations is directly proportional to the number of stem cell divisions. Thus, they are inevitable in highly proliferative tissues such as human hematopoietic system. Luckily, most mutations fall either within noncoding sequences or confer no functional consequences even when affecting protein-coding or regulatory DNA fragments. The probability of at least one of these mutations affecting the function of HSCs self-renewal and/or differentiation increases over time and may lead to the relative expansion of the mutated clone. Even though extrinsic factors or hereditary predisposition may further modulate the mutational rate and ultimately shape the clonal architecture of hematopoietic output, CH related to aging in otherwise healthy individuals (ARCH/CHIP) is considered a “sporadic”, mostly age-mediated process [17–19].

In addition to sporadic CH, the relative dominance of individual clone(s) can represent an adaptive mechanism to an extrinsic or intrinsic stress that occurs at the HSC level. Below we will discuss the nature and possible biological explanations for CH in acquired and inherited BMFs.

5. Clonal hematopoiesis and acquired bone marrow failure

CH is frequently associated with acquired BMF (Table 1). However, it is not entirely clear whether CH itself can predispose to BMF or better adapted hematopoietic clones gain survival advantage over unmutated counterparts in the presence of various selective pressures. Several retrospective studies have demonstrated that CH may evolve to MDS or AML over time [20,21].

Table 1.

The frequency and nature of CH in various BMFs.

| Type of stress | Stress | Most frequent CH alteration | Frequency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic/Intrinsic | Aging | DNMT3A | 8 | [19] |

| TET2 | 2 | [19] | ||

| ASXL1 | 2 | [19] | ||

| Extrinsic | AA | DNMT3A | 9 | [5] |

| ASXL1 | 13 | [5] | ||

| BCOR | 6 | [5] | ||

| PNH | TET2 | 8 | [3] | |

| SUZ12 | 3 | [3] | ||

| U2AF1 | 3 | [3] | ||

| ASXL1 | 3 | [3] | ||

| JAK2 | 5 | [3] | ||

| Chemotherapy | TP53 | 2 | [37] | |

| PPM1D | 10 | [37] | ||

| Intrinsic | DC | Backmutation | 50 | [45] |

| TERT promoter | 5 | [46] | ||

| FA | Gene conversion | 9 | [48] | |

| FANC point mutation | Case report | [49] | ||

| FANC frameshift mutation | Case series | [50] | ||

| SDS | Isochromosome 7q | 44 | [55] | |

| Monosomy 7 | 40 | [56] | ||

| Deletion 20q | 22 | [59] | ||

| TP53 | 48 | [42] | ||

| SCN | CSF3R | 78 | [62] | |

| MIRAGE syndrome | Deletion 7q | 18 | [63] | |

| UPD7q | 20 | [64] |

AA, aplastic anemia; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; DC, dyskeratosis congenita; FA, Fanconi anemia; SCN, Severe congenital neutropenia; SDS, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome; UPD, uniparental disomy.

On the other hand, in immune mediated BMFs, such as AA, certain mutations may provide survival advantage in the context of the autoimmune attack on HSCs.

5.1. Aplastic anemia

Acquired AA is an immune mediated bone marrow failure where autologous cytotoxic T cells attack HSCs. CH associated with AA is thought to represent a mechanism of immune escape. The most common example is a relative expansion of PIGA deficient HSC also known as PNH clone [22,23]. The small PNH clones can be present in healthy individuals but they lack competitive advantage under homeostatic condition. However, external pressure such as HSC-directed immune attack provides an environment where GPI-deficient cells are better fit and outcompete unmutated counterparts [24,25]. It has been postulated that GPI itself or GPI-anchored protein might serve as a target antigen [26]. A similar mechanism is represented by the occurrence of inactivating mutations or loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) of one of the HLA class I alleles, favoring the remaining allele, which confers a resistance against the autoreactive cytotoxic T cells [27].

The mechanism of increased HSC-fitness by other somatic mutations is less clear. Similarly to sporadic CHIP, DNMT3A, and ASXL1 are seen in up to 15% of patients with AA [4,5,27–29]. Additionally, mutations in transcriptional corepressors BCOR and BCORL1 are among the most frequently mutated genes in CH associated with AA. The exact impact of these mutations on stem cell fitness in the setting of immune pressure is not well understood [30]. While clones carrying DNMT3A and ASXL1 mutations tend to expand over time and impose higher risk of transformation to MDS/AML, clones with BCOR and BCORL1 mutations remain stable and rarely progress to myeloid malignancies [4].

Another manner through which HSCs can acquire resistance to the immune stress generated by AA is represented by the acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities. An acquired LOH of chromosome 7 is relatively common in AA and frequently associated with MDS/AML progression [31].

5.2. PNH

Similarly to AA, an increased autoimmunity against HSCs [32] is the main mechanism behind bone marrow failure in PNH. Even though less often, PNH may evolve to MDS/AML likely as a result of immune-mediated pressure selecting for clones which, although more resistant to the autoimmune stress, have a higher probability of MDS/AML evolution [33]. Somatic mutations normally occurring in myeloid malignancies (TET2, SUZ12, U2AF1, ASXL1, JAK2) can also be found in PNH patients and may either precede PIGA loss, arise as a subclone in the PIGA-mutated clone or represent an independent clone [3]. Interestingly, the lack or recurrent mutations may suggest that clonal evolution in PNH is rather due to an acquisition of random mutations related to proliferative stress imposed on HSC rather than shaped by extrinsic immune stress.

5.3. Myelodysplastic Syndromes

The evolution from CH to MDS is generally accepted to follow the multiple hit theory [34]. Even though the risk of CHIP progressing to myeloid malignancies is estimated to be <1% per year, patients with CCUS presenting with more than 2 mutations have an evolution rate of 90% at 5 years, while CCUS with one mutation has an evolution rate of 50% at 5 years [11]. Thus, CCUS with multiple mutations should be considered an early hematologic malignancy. Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that some patients diagnosed with CCUS do not progress to MDS/AML.

One possible explanation could be the lack of precise definition of CCUS as it may also encompass patients with “benign” CH and cytopenias that are independent of the clonal process. Thus, the term CCUS should be applied to patients with cytopenias related to clonal expansion of hematopoietic cells. We have previously proposed to apply a VAF cut-off of >20% and no alternative explanations for cytopenias [8]. Nonetheless, large prospective studies are still needed to establish more precise qualitative and quantitative characteristics of CH with cytopenia to better define this entity.

In the light of an adaptive mechanism it was observed that patients with CH are more likely to progress to MDS/AML after exposure to various chemotherapies for unrelated malignancies [35–37]. Patients with TP53 and PPM1D mutations were shown to have a higher likelihood of evolving to MDS/AML when treated with chemotherapy [38,39]. It is likely that randomly occurring TP53 and PPM1D mutations provide no clonal advantage under homeostatic conditions but are capable of resisting genotoxic stress associated with chemo- and or radiotherapy. Moreover, the clone often losses the wild-type allele, resulting in a complete loss-of-function that ultimately leads to accumulation of additional chromosomal defects and leukemic transformation [14,15,40,41].

6. Clonal hematopoiesis and inherited bone marrow failures

Inherited BMFs (iBMF) arise as a consequence of germline HSC defect, ranging from short telomere syndromes (STS) (Dyskeratosis congenita; DC)), increase in DNA damage (Fanconi anemia; FA)), impaired ribosome biogenesis (Shwachman-Diamond syndrome; SDS), granulocyte lineage stress (severe congenital neutropenia; SCN)) and SAMD9/SAMD9L mutations (MIRAGE syndrome) [42]. In the setting of internally imposed stress, there is a selective pressure for HSCs to acquire better fitness in order to sustain hematopoietic output. This can be achieved through several mechanisms including the emergence of compensatory mutations or chromosomal changes varying according to the pathogenic mechanism of the condition in which they occur. This, however, may come at a cost of higher rate of MDS/AML transformation. IBMFs vary greatly in terms of hematologic phenotype ranging from unilineage cytopenia to global HSC failure as well as the propensity for and the latency of malignant transformation [6]. The recent applications of high-throughput parallel sequencing technique have shed more light on biological and clinical consequences of CH in BMF (Figure 1).

STS are a group of heterogenous diseases characterized by defective telomere maintenance caused by an inherited defect in genes involved in telomerase complex [43]. Early onset bone marrow failure and progression to MDS/AML are the major causes of mortality [44]. CH is common in these patients, but the spectrum of acquired somatic mutations is rather distinct and differs from ARCH. This is likely dictated by a unique mechanism, specifically telomere attrition, leading to a global stem cell defect. Thus, genetic or functional correction of the germline defect would provide a relative advantage over less fit hematopoiesis. In fact, the competitive advantage of the hematopoietic clone with somatic reversion of DKC1 has been observed in DC patients [45]. Similarly, mutations in the promoter of the wild type TERT allele which lead to the subsequent increase in the expression of the functional allele have been reported [46].

FA is an inherited bone marrow failure syndrome characterized by pancytopenia, predisposition to malignancies and various congenital anomalies [47]. This condition is caused by mutations in one of approximately 17 FA genes. The defect in FANC complex results in genomic instability due to altered repair of interstrand DNA crosslinks. Bone marrow failure in FA patients is believed to be caused by endogenous aldehyde-induced toxicity and/or DNA damage-induced p53 activation, which result in the attrition of HSCs. Similarly, chemotherapeutic agents are particularly toxic in patient with FA which further limits treatment option in patients with high prevalence for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. Given the underlying defect in DNA repair pathway it is no surprise that clonal evolution and malignant transformation are frequent in FA patients. Studies in patients with stable or improving cytopenias demonstrated that acquired somatic mutations in hematopoietic cells may partially or fully correct the germline defect in one of the mutant alleles and restore mutated gene function, a mechanism known as somatic reversion [48]. This correction may occur through back mutation to a wild-type allele (full correction), compensatory missense mutations and/or deletion/insertion that produces fully or partially functional protein and intragenic cross-over. The latter event occurs in compound heterozygotes where mitotic cross-over between two mutated loci produces one chromatid with reconstituted wild type gene [48–50]. Such corrected HSC clone is capable of improving hematopoietic output and alleviating pancytopenia [51]. A very strong selection pressure and underlying genomic instability can explain a relatively frequent occurrence of somatic reversion in FA patients [52].

SDS, characterized by BMF, skeletal abnormalities and malnutrition, is a condition caused by the biallelic mutation of the SBDS gene. These mutations are generally represented by one null and one hypomorphic mutation which lead to an impaired ribosome biogenesis, increased p53 activation and abnormal apoptosis [53–56]. SBDS is part of a complex that cleaves EIF6 off the 60S ribosomal subunit, a necessary step in proper ribosome formation. EIF6 retention caused by nonfunctional SBDS leads to ribosome formation defect and impaired translation [57]. CH involving isochromosome 7q, deletion 20q, EIF6 or TP53 mutations provides a compensatory mechanism allowing for partially reversion of translational constrains imposed by mutant SBDS. Isochromosome 7q determines the duplication of the hypomorphic SBDS gene, leading to an improved ribosome biogenesis [6]. In the case of 20q deletion it is thought that the advantage offered by this abnormality is related to the EIF6 haploinsufficiency as the cleavage of EIF6 is impaired in SDS. Thus, a quantitative reduction of EIF6 may partially reestablish ribosome biogenesis [57–59]. The presence of CH with EIF6 mutations is also common in SDS and results in either quantitative reduction of the EIF6 or defective protein unable to bind to 60S subunit. Interestingly, patients with EIF6 CH are less likely to progress to myeloid malignancies [60]. HSCs can also adapt to the impaired ribosome biogenesis by “ignoring” the stress induced by it. This can be achieved through the acquisition of TP53 mutations that lead to a better fitness of HSCs on one hand, but may result in an increased probability of the cell to acquire additional gene mutations and to evolve to MDS/AML on the other [42].

SCN is caused by germline mutations in ELANE and less frequently in HAX1 and G6PC3 that lead to enhanced granulocyte lineage stress [61]. This defect may be overcome in an exogenous manner by using recombinant G-CSF. Thus, a hematopoietic clone with an acquired activation mutation in GCSF receptor, CSF3R, may restore granulopoiesis. This proliferative advantage may come at cost of increased risk of MDS/AML [62].

MIRAGE syndrome is an iBMF caused by germinal mutations in SAMD9/SAMD9L and characterized by pancytopenia and increased risk for MDS/AML development. Since both genes are located on long arm of chromosome 7, somatic reversion involving the loss of mutated allele through deletion has been described. As expected, CH with deletion 7q significantly increases the likelihood of progression to MDS/AML [63,64].

7. Diagnostic approach and surveillance

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the field of hematology and dramatically advanced our knowledge of BMFs. It also became a powerful tool not only in the laboratory but also in hematology practice for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. In the era of targeted therapies, the sequencing results became essential in therapeutic decision making. Although extremely helpful in certain circumstances, the interpretation of NGS results must be done with caution. Given its relatively high prevalence in the general population, screening for CH is not recommended in otherwise asymptomatic individuals with normal hemogram, but it could pose a helpful strategy in BMFs

7.1. NGS in BMF diagnosis

As iBMFs are frequently caused by germline genetic defects, NGS is useful as a diagnostic test in conjunction with thorough medical evaluation, morphological blood and bone marrow examination as well as disease-specific molecular and cytogenetic studies [65]. Conversely, the presence of somatic mutations in the context of acquired BMFs work-up is often not sufficient to make a correct diagnosis. It is however, a very helpful auxiliary test to assess the clonal the burden and genetic signature of the underlying clonal process [66].

7.2. NGS in BMF surveillance

The presence of CH in BMF is not always associated with increased risk of malignant transformation. Even though, the data on leukemogenic potential of various mutations are slowly emerging, the distinction between truly oncogenic clone and the ones with somatic correction of the underlying genetic defect (as in iBMF) or acquired immune-escape mechanism (as in acquired BMF) remains challenging. The emergence of hematopoietic clone with alterations in tumor suppressor or putative oncogene would likely raise the concerns and trigger closer clinical and molecular surveillance but the clinical practice guidelines have not been established. The prospective studies utilizing established BMF registries are necessary to augment our understanding of the natural history of CH in BMFs and to establish the risk assessment systems in order for timely introduction of more aggressive antileukemic therapies and/or referral for allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Summary

The acquisition of CH is frequent in BMFs and often represents an adaptive mechanism to either extracellular or intrinsic stressors augmenting stem cell fitness and hematopoietic output. The nature of CH depends deeply on the underlying etiology of BMF. In case of external insult, somatic mutations and or chromosomal alteration may provide a survival advantage by evasion of HSC-directed immune attack. Acquired genetic alterations in hematopoietic clones may also result in somatic reversion of the inherited defects in iBMF either through the correction of germline mutations or indirect compensatory mechanism. Occasionally such correction, particularly when involving putative oncogenes or tumor suppressors, may increase the risk of malignant transformation and subsequent evolution to myeloid malignancies. Even though the leukemic transformation potential has been linked to specific genetic alterations there are currently no guidelines regarding surveillance in BMFs based on the presence and molecular characteristics of CH. Further studies utilizing BMFs registries are needed to optimize the clinical management and surveillance strategies in patient with BMFs allowing for timely implementation of potentially curative therapies.

Practice points.

NGS is a powerful diagnostic tool in inherited BMF and is a useful auxiliary test in acquired BMF but the results should be interpreted with caution

Clonal hematopoiesis is frequent in BMFs and provides an adaptation mechanism to either extrinsic stress or germline HSC defect

The genetic characteristics of CH may be an important determinant of its oncogenic potential.

Surveillance of patients with BMFs may provide important prognostic clues and facilitate timely implementation of appropriate therapies

Research agenda.

Prospective trials utilizing BMF registres are required to further determine the clinical consequences of CH

Surveillance strategies and disease specific prognostic systems are essential to improve clinical management of BMFs and timely implementation of potentially curative therapies

Better understanding of molecular underpinnings of HSC fitness and adaptation to intra and extracellularly imposed constrictions may result in novel therapeutic approaches focused on improved hematopoietic output and amelioration of bone marrow failure.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grants K08 HL136894 and R01 HL156144.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Moore CA, Krishnan K. Bone Marrow Failure. StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Trowbridge JJ. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors Driving Hematopoietic Stem Cell Aging and Bone Marrow Failure. Blood 2019;134:SCI-35–SCI-35. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shen W, Clemente MJ, Hosono N, Yoshida K, Przychodzen B, Yoshizato T, et al. Deep sequencing reveals stepwise mutation acquisition in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. J Clin Invest 2014;124:4529–4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, Makishima H, Yoshida K, Townsley D, et al. Somatic Mutations and Clonal Hematopoiesis in Aplastic Anemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kulasekararaj AG, Jiang J, Smith AE, Mohamedali AM, Mian S, Gandhi S, et al. Somatic mutations identify a subgroup of aplastic anemia patients who progress to myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 2014;124:2698–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tsai FD, Lindsley RC. Clonal hematopoiesis in the inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood 2020;136:1615–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Doulatov S, Notta F, Laurenti E, Dick JE. Hematopoiesis: a human perspective. Cell Stem Cell 2012;10:120–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gondek LP, DeZern AE. Assessing clonal haematopoiesis: clinical burdens and benefits of diagnosing myelodysplastic syndrome precursor states. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, Lindsley RC, Sekeres MA, Hasserjian RP, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2015;126:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].DeZern AE, Malcovati L, Ebert BL. CHIP, CCUS, and Other Acronyms: Definition, Implications, and Impact on Practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2019;39:400–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Malcovati L, Gallì A, Travaglino E, Ambaglio I, Rizzo E, Molteni E, et al. Clinical significance of somatic mutation in unexplained blood cytopenia. Blood 2017;129:3371–3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Valent P, Bain BJ, Bennett JM, Wimazal F, Sperr WR, Mufti G, et al. Idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance (ICUS) and idiopathic dysplasia of uncertain significance (IDUS), and their distinction from low risk MDS. Leuk Res 2012;36:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Watson CJ, Papula AL, Poon GYP, Wong WH, Young AL, Druley TE, et al. The evolutionary dynamics and fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis. Science 2020;367:1449–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eskelund CW, Husby S, Favero F, Klausen TW, Rodriguez-Gonzalez FG, Kolstad A, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis evolves from pretreatment clones and stabilizes after end of chemotherapy in patients with MCL. Blood 2020;135:2000–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hsu JI, Dayaram T, Tovy A, De Braekeleer E, Jeong M, Wang F, et al. PPM1D Mutations Drive Clonal Hematopoiesis in Response to Cytotoxic Chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell 2018;23:700–713.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Steensma DP, Ebert BL. Clonal Hematopoiesis after Induction Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1244–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].de Haan G, Lazare SS. Aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 2018;131:479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zink F, Stacey SN, Norddahl GL, Frigge ML, Magnusson OT, Jonsdottir I, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis, with and without candidate driver mutations, is common in the elderly. Blood 2017;130:742–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Frick M, Chan W, Arends CM, Hablesreiter R, Halik A, Heuser M, et al. Role of Donor Clonal Hematopoiesis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, Chen WC, Brandwein JM, Gupta V, et al. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature 2014;506:328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Desai P, Mencia-Trinchant N, Savenkov O, Simon MS, Cheang G, Lee S, et al. Somatic mutations precede acute myeloid leukemia years before diagnosis. Nat Med 2018;24:1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schubert J, Vogt HG, Zielinska-Skowronek M, Freund M, Kaltwasser JP, Hoelzer D, et al. Development of the glycosylphosphatitylinositol-anchoring defect characteristic for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in patients with aplastic anemia. Blood 1994;83:2323–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kawaguchi K, Wada H, Mori A, Takemoto Y, Kakishita E, Kanamaru A. Detection of GPI-anchored protein-deficient cells in patients with aplastic anaemia and evidence for clonal expansion during the clinical course. Br J Haematol 1999;105:80–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dingli D, Luzzatto L, Pacheco JM. Neutral evolution in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:18496–18500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cooper JN, Young NS. Clonality in context: hematopoietic clones in their marrow environment. Blood 2017;130:2363–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Savage WJ, Barber JP, Mukhina GL, Hu R, Chen G, Matsui W, et al. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein deficiency confers resistance to apoptosis in PNH. Exp Hematol 2009;37:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Babushok DV, Perdigones N, Perin JC, Olson TS, Ye W, Roth JJ, et al. Emergence of clonal hematopoiesis in the majority of patients with acquired aplastic anemia. Cancer Genet 2015;208:115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lane AA, Odejide O, Kopp N, Kim S, Yoda A, Erlich R, et al. Low frequency clonal mutations recoverable by deep sequencing in patients with aplastic anemia. Leukemia 2013;27:968–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Heuser M, Schlarmann C, Dobbernack V, Panagiota V, Wiehlmann L, Walter C, et al. Genetic characterization of acquired aplastic anemia by targeted sequencing. Haematologica 2014;99:e165–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ogawa S. Clonal hematopoiesis in acquired aplastic anemia. Blood 2016;128:337–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dumitriu B, Feng X, Townsley DM, Ueda Y, Yoshizato T, Calado RT, et al. Telomere attrition and candidate gene mutations preceding monosomy 7 in aplastic anemia. Blood 2015;125:706–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hill A, DeZern AE, Kinoshita T, Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Oni SB, Osunkoya BO, Luzzatto L. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: evidence for monoclonal origin of abnormal red cells. Blood 1970;36:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sperling AS, Gibson CJ, Ebert BL. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndrome: from clonal haematopoiesis to secondary leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gillis NK, Ball M, Zhang Q, Ma Z, Zhao Y, Yoder SJ, et al. Clonal haemopoiesis and therapy-related myeloid malignancies in elderly patients: a proof-of-concept, case-control study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Takahashi K, Wang F, Kantarjian H, Doss D, Khanna K, Thompson E, et al. Preleukaemic clonal haemopoiesis and risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Swisher EM, Harrell MI, Norquist BM, Walsh T, Brady M, Lee M, et al. Somatic Mosaic Mutations in PPM1D and TP53 in the Blood of Women With Ovarian Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:370–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wong TN, Ramsingh G, Young AL, Miller CA, Touma W, Welch JS, et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2015;518:552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gibson CJ, Lindsley RC, Tchekmedyian V, Mar BG, Shi J, Jaiswal S, et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated With Adverse Outcomes After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation for Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1598–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bernard E, Nannya Y, Hasserjian RP, Devlin SM, Tuechler H, Medina-Martinez JS, et al. Implications of TP53 allelic state for genome stability, clinical presentation and outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Med 2020;26:1549–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jasek M, Gondek LP, Bejanyan N, Tiu R, Huh J, Theil KS, et al. TP53 mutations in myeloid malignancies are either homozygous or hemizygous due to copy number-neutral loss of heterozygosity or deletion of 17p. Leukemia 2010;24:216–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Xia J, Miller CA, Baty J, Ramesh A, Jotte MRM, Fulton RS, et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in congenital neutropenia. Blood 2018;131:408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Nelson ND, Bertuch AA. Dyskeratosis congenita as a disorder of telomere maintenance. Mutat Res 2012;730:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Knight S, Vulliamy T, Copplestone A, Gluckman E, Mason P, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis Congenita (DC) Registry: identification of new features of DC. Br J Haematol 1998;103:990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Perdigones N, Perin JC, Schiano I, Nicholas P, Biegel JA, Mason PJ, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Am J Hematol 2016;91:1227–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Maryoung L, Yue Y, Young A, Newton CA, Barba C, van Oers NSC, et al. Somatic mutations in telomerase promoter counterbalance germline loss-of-function mutations. J Clin Invest 2017;127:982–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Auerbach AD. Fanconi anemia and its diagnosis. Mutat Res 2009;668:4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lo Ten Foe JR, Kwee ML, Rooimans MA, Oostra AB, Veerman AJ, van Weel M, et al. Somatic mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: molecular basis and clinical significance. Eur J Hum Genet 1997;5:137–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Gross M, Hanenberg H, Lobitz S, Friedl R, Herterich S, Dietrich R, et al. Reverse mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: natural gene therapy via molecular self-correction. Cytogenet Genome Res 2002;98:126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Waisfisz Q, Morgan NV, Savino M, de Winter JP, van Berkel CG, Hoatlin ME, et al. Spontaneous functional correction of homozygous fanconi anaemia alleles reveals novel mechanistic basis for reverse mosaicism. Nat Genet 1999;22:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hamanoue S, Yagasaki H, Tsuruta T, Oda T, Yabe H, Yabe M, et al. Myeloid lineage-selective growth of revertant cells in Fanconi anaemia. Br J Haematol 2006;132:630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rageul J, Kim H. Fanconi anemia and the underlying causes of genomic instability. Environ Mol Mutagen 2020;61:693–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Elghetany MT, Alter BP. p53 protein overexpression in bone marrow biopsies of patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome has a prevalence similar to that of patients with refractory anemia. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:452–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dror Y, Freedman MH. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome marrow cells show abnormally increased apoptosis mediated through the Fas pathway. Blood 2001;97:3011–3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dror Y. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;45:892–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Woods WG, Roloff JS, Lukens JN, Krivit W. The occurrence of leukemia in patients with the Shwachman syndrome. J Pediatr 1981;99:425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Weis F, Giudice E, Churcher M, Jin L, Hilcenko C, Wong CC, et al. Mechanism of eIF6 release from the nascent 60S ribosomal subunit. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2015;22:914–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ceci M, Gaviraghi C, Gorrini C, Sala LA, Offenhäuser N, Marchisio PC, et al. Release of eIF6 (p27BBP) from the 60S subunit allows 80S ribosome assembly. Nature 2003;426:579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pressato B, Valli R, Marletta C, Mare L, Montalbano G, Lo Curto F, et al. Deletion of chromosome 20 in bone marrow of patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, loss of the EIF6 gene and benign prognosis. Br J Haematol 2012;157:503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kennedy AL, Myers KC, Bowman J, Gibson CJ, Camarda ND, Furutani E, et al. Distinct genetic pathways define pre-malignant versus compensatory clonal hematopoiesis in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Commun 2021;12:1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Xia J, Bolyard AA, Rodger E, Stein S, Aprikyan AA, Dale DC, et al. Prevalence of mutations in ELANE, GFI1, HAX1, SBDS, WAS and G6PC3 in patients with severe congenital neutropenia. Br J Haematol 2009;147:535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Germeshausen M, Ballmaier M, Welte K. Incidence of CSF3R mutations in severe congenital neutropenia and relevance for leukemogenesis: Results of a long-term survey. Blood 2007;109:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Narumi S, Amano N, Ishii T, Katsumata N, Muroya K, Adachi M, et al. SAMD9 mutations cause a novel multisystem disorder, MIRAGE syndrome, and are associated with loss of chromosome 7. Nat Genet 2016;48:792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pastor VB, Sahoo SS, Boklan J, Schwabe GC, Saribeyoglu E, Strahm B, et al. Constitutional SAMD9L mutations cause familial myelodysplastic syndrome and transient monosomy 7. Haematologica 2018;103:427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Muramatsu H, Okuno Y, Yoshida K, Shiraishi Y, Doisaki S, Narita A, et al. Clinical utility of next-generation sequencing for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Genet Med 2017;19:796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Skibenes ST, Clausen I, Raaschou-Jensen K. Next-generation sequencing in hypoplastic bone marrow failure: What difference does it make? Eur J Haematol 2021;106:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]