Abstract

Salmonellosis, caused by Salmonella spp., is a widely reported foodborne zoonosis frequently associated with ingestion of poultry products. Salmonella vaccination of chickens can be used to reduce bacterial shedding and risk of human infection. To determine Salmonella burden in chicken farms, culture methods of environmental samples that require a turn-around time of 5–7 days are usually used. Rapid screening using molecular assays such as PCR of pre-enriched broth has been reported for Salmonella spp. detection in feed, floor dust, and drag swabs within 2–3 days. Here we report an adaptation of the method for detection of Salmonella in poultry dust samples collected using a settle plate method under experimental conditions. Key features:

-

•

Passive dust sample collection using dry settle plates without media suspended from dropper lines of drinkers.

-

•

Small amount of sample required for the pre-enrichment process.

-

•

Quantification of Salmonella DNA with high sensitivity using an inexpensive extraction protocol.

Keywords: Salmonella, Chicken, Disease monitoring, Poultry dust, qPCR

Graphical abstract

Specifications Table

| Subject Area: | Veterinary Science and Veterinary Medicine |

| More specific subject area: | Environmental microbiology |

| Method name: | Detection of Salmonella in poultry dust |

| Name and reference of original method: | Gole et al., Shedding of Salmonella in single age caged commercial layer flock at an early stage of lay. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014 [5]. De Medici et al., Evaluation of DNA extraction methods for use in combination with SYBR green I real-time PCR to detect Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis in poultry. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003 [11]. |

| Resource availability: | All consumables and equipment required are described in the manuscript. |

Method details

Salmonella spp. cause fowl typhoid and pullorum diseases in poultry and are responsible for non-typhoidal Salmonella infection in humans. Prevention of Salmonella infection in chicken flocks is an important step in reducing salmonellosis outbreaks in humans. Vaccination with live attenuated vaccine of certain strains such as e.g. S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium and S. Gallinarum has been commonly used in the field to prevent the disease, and proven to be useful to reduce bacterial shedding [1,2]. To monitor Salmonella shedding patterns in vaccinated and unvaccinated flocks, a combination of litter, drag swab, dust swab, feed and egg belt swab are usually used [3,4]. However, extraction of genomic DNA from these various sample types is expensive and time-consuming due to the requirement for faecal or soil DNA extraction kits [4] or overnight processing of extracted DNA samples [5], restricting the success of routine monitoring of Salmonella in poultry flocks.

Dust sample collection using settle plates has been a useful tool for routine monitoring of pathogens in poultry flocks [6]. The use of media-free, dry settle plates enables easy collection of a stable material, dry dust, from which nucleic acid extraction can effectively be done using inexpensive extraction kits [7]. Even less costly methods such as the boiling method of DNA extraction have been effective for Salmonella detection from different food specimens [8]. However, it is unknown if this method would be effective for Salmonella detection in dust samples.

This study reports the longitudinal tracking of Salmonella using dust samples collected on dry settle plates from an experimental flock exposed to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT 135 at 1 day of age, based on PCR detection of Salmonella invA gene in dust with and without enrichment and with two methods of DNA extraction: a commercial kit and a method based on boiling of samples enriched over-night in buffered peptone water (BPW). The invA gene-based PCR was chosen for its ability to detect multiple Salmonella spp. as a screening tool. Furthermore, the samples used for this protocol development were derived from an experimental flock challenged with S. Typhimurium PT 135, and no other serotypes were identified by culture and biochemical tests from monitoring of cloacal swabs and drag swabs during the experiment [9]. In samples positive for the invA gene DNA, multiplex PCRs would be required for the differentiation of specific Salmonella serovars according to the research and diagnostic needs.

Materials

Autoclave (HiclveTM, HV-85L, Hirayama)

Biosafety cabinet class II or Bunsen burner

Buffered Peptone Water (BPW, Oxoid, Cat. no. CM0509B, Australia)

Colony counter (SCC100, Selby®)

Corbett Robot

Digital microbalance

Distilled water

Erlenmeyer flask (conical flask)

Glass pipette (10 ml)

Heat block

Incubator (Labmaster®)

ISOLATE II Genomic DNA Kit (Bioline, Cat. No. BIO-52067, Australia)

Microcentrifuge tubes

PCR tubes

Petri dishes

Pipette filter tips

Pipettes (10, 100 and 1000 µl)

Polypropylene L-shaped spreaders (Wiltronics, Cat. No. TL1350, Australia)

PYREX® screw cap culture tubes with phenolic caps (Thomas Scientific, Cat. no. 9212C21, USA)

RNase-free water

Rotor-gene qPCR system

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (strain: ACM 3598)

Screw cap bottle/media bottle (Thomas Scientific, Cat. no.1743G56, USA)

Settle plates

Test tube rack

Test tubes

Vortex

Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) Agar (Oxoid, Cat. no. CM0469B, Australia)

Protocol

Sample collection

Dust samples (n = 40) were collected in a curtain sided conventional experimental chicken house divided into 16 pens of which 7 pens containing 210 Hy-Line Brown layer chickens (30 birds/pen) and 9 pens remaining empty as previously described [9]. Briefly, the birds of 6 pens were exposed to a field isolate of S. Typhimurium DT 135 using a seeder bird technique at 0 day of age and birds of remaining pen were unchallenged control (Supplementary Table 1). At weeks 10 and 16 of age, the birds were vaccinated with a live Aro-A deletion mutant vaccine against S. Typhimurium strain STM1 (VaxsafeST, Biopropeties Australia, Ringwood, Victoria) in 4 pens of the 6 challenged pens by intramuscular injection of approximately 2.3 × 107 colony forming unit (CFU)/bird.

Dust samples were collected at 8.5, 9, 9.5, 12, 14, 15, 16, 18 and 30 weeks of age using a dry plastic settle plate with a surface area of 520 cm2. Settle plates were installed in five sites within the house near pens 13, 14, 17, 19 and 23. Samples from each site were collected into separate zip-lock bags by shaking and scraping the dust deposited on the surface of the settle plate into the bag then sealing it. After collection, samples were stored at -20 °C and then transported to the University of New England for further storage at -80 °C prior to use. Dust samples were homogenised by vortexing and divided into two aliquots before further testing. Additionally, drag swabs (1 swab/pen) of individual bird pens were collected from 6 challenged pens using two tampons per pen soaked in sterile BPW at 8, 12, 16 and 18 weeks of age and were cultured for the presence of Salmonellae using the Australian Standard method (AS 5013.10-2009) [10]. This involved incubation and inoculation into modified semisolid Rappaport-Vassiliadis medium, Hektoen and xylose-lysine-deoxycholate media and chromogenic agar. Presumptive Salmonella colonies were confirmed serologically with poly-O and poly-H antisera by the slide agglutination technique after sub-culture on a nutrient agar slope [9]. The experiment was approved by the University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee (Approval no. 2017/1207).

Dust sample processing and extraction

-

1.Samples enriched for Salmonella: Approximately 100 mg of dust was resuspended in 10 ml of BPW and mixed by vortexing for 20–30 s. For samples for which less than 100 mg was available, 10 to 50 mg of dust was used. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Enriched samples were extracted by two methods.

-

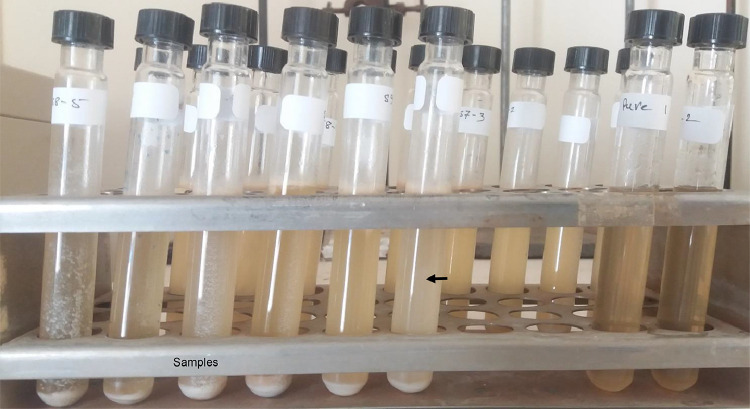

(i)Boiling method: 1 ml of enriched sample was pipetted from the middle of tube (Fig. 1) and was transferred to 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 × g. The supernatant was discarded carefully. The pellet was resuspended using 300 µl of molecular water by vortexing followed again by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min and discarding of the supernatant. The pellet was resuspended using 200 µl of molecular grade water by vortexing. The microcentrifuge tube was incubated at 100 °C for 15 min using a heat block then immediately chilled on ice for 15 min. The sample was then centrifuged for 13,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and incubated again at 100 °C for 10 min then chilled immediately on ice for 10 min. The sample was then mixed with a pipette prior to use in the PCR reaction. This method was described previously by De Medici et al. [11], but the centrifugation was performed at 13,000 × g in this experiment instead of 14,000 × g.

-

(ii)Extraction kit: 1 ml of the pre-enriched sample was extracted using the ISOLATE II Genomic DNA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Extracted DNA was eluted in a volume of 100 µl.

-

(i)

-

2.

Non-enriched dust samples: Five mg of dust was extracted using the ISOLATE II Genomic DNA kit and DNA eluted in a final volume of 100 µl as described by Ahaduzzaman et al. [7]. The boiling method was not used to extract DNA from non-enriched dust samples because of the reduced sensitivity of this method and the insufficient amount of dust samples to carry on this test.

-

3.

DNA concentration: Extracted DNA quality and quantity were measured using a spectrophotometer (NanoDropND-1000 UV-Vis) and stored at -20 °C until use.

Fig 1.

Buffered peptone water broth media after incubation of 100 mg of dust samples in 10 ml of BPW at 37 °C for 18 h. Dust formed a sediment at the bottom of the broth culture tubes and turbidity was observed mostly in the middle of the tube. The arrow mark indicates the pipetting site for transfer of the pre-enriched sample for DNA extraction.

Real-time qPCR for Salmonella

-

1.

Development of Salmonella standards: A suspension of S. Typhimurium was 10-fold diluted from 10−1 to 10−8 in molecular grade water. For the preparation of standards, DNA was extracted from each dilution by both the boiling method and the commercial extraction kit as described above. To quantify the Salmonella counts in each standard, 100 µl of the same bacterial suspension was plated by using spread plate technique as described by Sanders [12] on XLD agar plates with 6 replicates per dilution and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Colony counting was performed using a colony counter. Based on the number of enumerated colonies on agar plates, the concentration of Salmonella in the original suspension was calculated in CFU/ml. CFU was estimated using the standard formula of CFU = (Number of colony × dilution factor)/amount plated.

The sensitivity and amplification efficiency for both real-time PCR assays were tested by amplification of 10-fold serial dilutions of S. Typhimurium DNA samples. The threshold cycles were plotted against the log10 values of the initial number of S. Typhimurium DNA copies in the PCR to construct a standard curve for each assay. Linearity was observed with the following linear regression curves: y = -3.77x + 30.23 and y = -4.37x + 35.70 for the kit and boiling methods of extraction respectively, where y is the CT value and x is the log10 concentration of Salmonella. A high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.999) was attained for both methods, and a high amplification efficiency (87% by kit and 70% by boiling methods) was achieved. Therefore, it is considered that these assays produced an accurate quantification of Salmonella when the initial amount of Salmonella DNA in the PCR fell in the range of 1.00 × 100 to 1.09 × 105 copies/reaction for the kit extraction and 4.85 × 100 to 4.85 × 105 copies/reaction for the boiling method of extraction.

-

2.

Real-time qPCR conditions: Extracted DNA was tested for Salmonella by a qPCR using primers (forward: 5‘–AACGTGTTTCCGTGCGTAAT–3’ and reverse: 5‘–TCCATCAAATTAGCGGAGGC–3’) and TaqMan probe (5‘-FAM-TGGAAGCGCTCGCATTGTGG-BHQ-1-3’) targeting the invA gene [13]. Each 25 µl of real-time PCR reaction contained 0.5 µl of each primer (0.5 mM), 0.5 µl of probe (10 mM), 5 µl of template DNA (1:10 dilution in molecular water), 12.5 µl of 2 × master mix, and 6 µl of nuclease-free water. PCR conditions were 95 °C for 3 min, was followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. The standards developed following DNA extraction by each extraction method were used to quantify samples extracted by the same method. The results were analysed by the Rotor-Gene Q version 2.3.1.49 software and reported as Salmonella log10 CFU per gram of dust.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP v.14 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Salmonella CFU per g of dust (with or without enrichment) was analysed and expressed on the log10 scale. The proportion of samples positive for Salmonella are presented as number of positive samples by the total number of samples sampled (%) in each category (non-enriched kit, enriched kit, enriched boil, and drag swab) and McNemar's test was used for pairwise comparison to determine whether the proportions of PCR-positive samples were significantly different. Prevalence of Salmonella in drag swab and enriched dust at given sampling day linear association was explored. Analysis of variance was used to test the effects of sampling time and treatment effects with means and standard errors reported. Association between the methods of extraction of Salmonella CFU was analysed using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) test.

Method validation

Quality assessment results of extracted DNA are presented in Table 1. The 260/280 and 260/230 ratio were <1 in case of 97.5 to 100% of samples when DNA extraction was done from non-enriched dust samples using the extraction kit, and between 1.8 and 2 on 52.5 and 70% of samples when extraction was done from enriched dust using boiling method and extraction kit, respectively. This indicates that enrichment of samples prior to DNA extraction significantly improves the quality of the obtained DNA.

Table 1.

Proportion of extracted DNA quality extracted from poultry dust samples with and without overnight pre-enrichment in pre-enrichment in BPW using extraction kit and boiling methods. A 260/280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 is indicative of high DNA quality.

| Spectrophotometer DNA quality assessment parameter | Non-enriched KitN (%) |

Enriched KitN (%) |

Enriched BoilN (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 260/280 | 260/230 | 260/280 | 260/230 | 260/280 | 260/230 | |

| < 1 | 40 (100) | 39 (97.5) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10) | 12 (30) | 12 (30) |

| 1.0–1.49 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 3 (7.5) | 27 (67.50) |

| 1.5–1.79 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (12.50) | 6 (15) | 4 (10) | 1 (2.50) |

| ≥ 1.8–2.0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 28 (70) | 26 (65) | 21 (52.50) | 0 (0) |

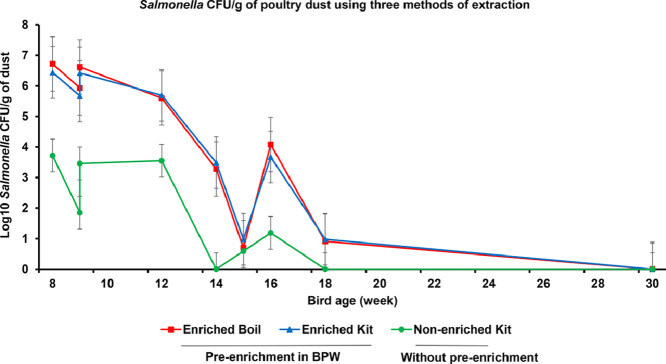

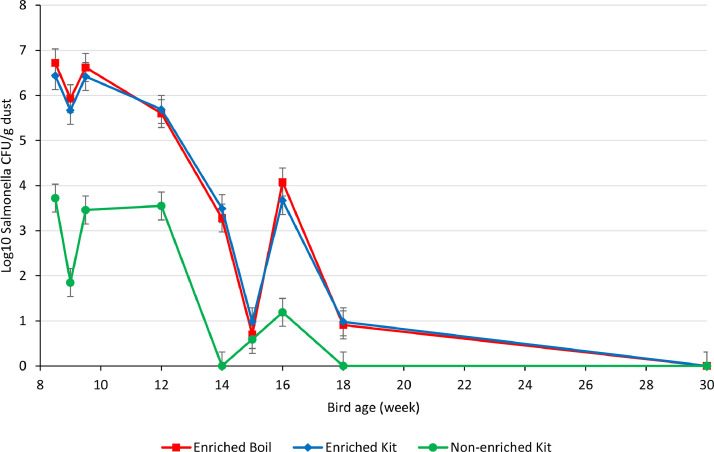

The proportion of dust samples positive for Salmonella increased with overnight enrichment (Table 2) particularly when bacterium concentrations were low. Overall, 62.5% (25/40) of samples were positive after enrichment while 40% (16/40) of non-enriched samples were positive (P = 0.003). When Salmonella levels were high, from weeks 8 to 12 of bird age (Fig. 2) all samples were positive irrespective of enrichment. However, for the samplings at 14–18 weeks, when Salmonella levels were 2–6 logs lower, only 20–40% samples were positive without enrichment while 20–80% of samples were positive after enrichment. No difference was observed in the detection pattern of Salmonella between kit and boiling method of extraction after enrichment (P = 1.00).

Table 2.

Ratio of Salmonella qPCR positive samples in dust with and without overnight pre-enrichment in pre-enrichment in BPW, compared to culture method of drag swabs.

| Age (weeks) | Salmonella positive/n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dust with enrichment | Dust without enrichment | P-value1 | Drag swab | P-value2 | |

| 8–8.5 | 4/4 (100) | 4/4 (100) | 1.00 | 6/6 (100) | 1.00 |

| 9 | 4/4 (100) | 2/4 (50) | 0.10 | - | |

| 9.5 | 2/2 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 1.00 | - | |

| 12 | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 1.00 | 6/6 (100) | 1.00 |

| 14 | 4/5 (80) | 0/5 (00) | 0.009 | - | |

| 15 | 1/5 (20) | 1/5 (20) | 1.00 | - | |

| 16 | 4/5 (80) | 2/5 (40) | 0.16 | 4/6 (66.7) | 1.00 |

| 18 | 1/5 (20) | 0/5 (00) | 0.29 | 4/6 (66.7) | 0.08 |

| 30 | 0/5 (00) | 0/5 (00) | 1.00 | - | |

| Total | 25/40a | 16/40b | 0.003 | 20/24a | 0.08 |

Different superscript letters (ab) indicate statistical significance

Comparison between dust with enrichment and dust without enrichment.

Comparison between dust with enrichment and drag swab.

-Sample not tested.

Fig. 2.

Salmonella load in dust samples enriched or not by incubation in BPW with DNA extraction by a commercial kit or a simple sample boiling method. Dust samples were collected at the indicated time points from experimental flock challenged with a field isolate of S. Typhimurium DT 135 using a seeder bird technique at 1 day of age and vaccinated with a non-propagative strain of live Salmonella vaccine at 10 and 16 weeks of age.

Compared to detection using drag swabs, there was no significant difference in the detection rates of enriched dust and drag swab samples on the same sampling days (P = 0.08) (Table 2). Linear association between Salmonella prevalence (%) in dust and drag swabs showed a strong positive relationship (r = 0.76), suggesting that Salmonella shed actively in faeces and found in litter can be detected in settled dust in the environment.

The level of Salmonella detected in dust (CFU/g) also depended on overnight enrichment of dust (P = 0.004) and bird age/day post challenge infection (P < 0.0001) but not by the extraction method used on enriched samples (Fig. 2). The level was similar (P = 0.94) for enriched samples extracted using a commercial kit (3.70 ± 0.31) or the boiling method (3.76 ± 0.31) and was lower (1.60 ± 0.31) for non-enriched samples extracted using the commercial kit (P < 0.001). Levels declined gradually to low levels at week 15, followed by a small increase at week 16, then a decline to low levels at week 18 with all samples negative at week 30.

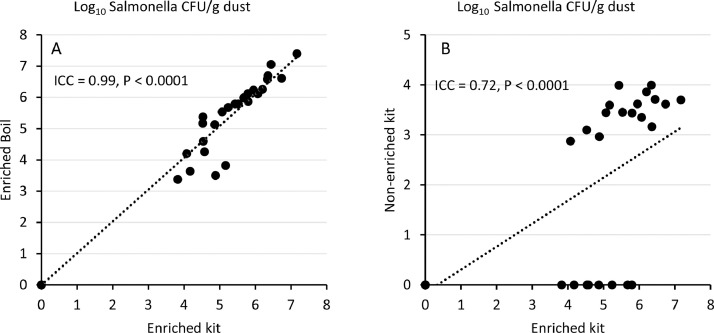

There was an almost perfect agreement between the real-time PCR results from enriched samples following DNA extraction by the boiling and commercial kit methods (ICC = 0.99, P < 0.0001, Fig. 3A). On the other hand, there was a moderate agreement between PCR values of enriched and non-enriched dust extracted by the commercial kit method (ICC = 0.72, P < 0.0001, Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A. Intraclass correlation coefficient of Log10Salmonella CFU/g of BPW enriched dust extracted by Kit and boiling method. Here, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.99, degrees of freedom (df) = 39 and P < 0.0001.B. intraclass correlation coefficient of Log10Salmonella CFU/g of non-enriched dust extracted by kit and BPW enriched dust extracted by kit. Here, the ICC value is 0.72, degrees of freedom (df) = 39 and P < 0.0001.

Longitudinal tracking of Salmonella in dust samples was possible after birds were challenged with Salmonella. Enrichment of dust samples in BPW improved sensitivity and Salmonella detection pattern using qPCR. No difference was observed between the boiling method and extraction kit method. Collection of dust samples using settle plates followed by enrichment in BPW, extraction of DNA using the boiling method and qPCR analysis may offer a cost effective and practical method of Salmonella monitoring in poultry populations. Dust is a stable, easily collected population level sample and qPCR of dust for pathogen detection offers advantages in speed, simplicity and potentially sensitivity over methods based on culture of the organism.

Additional information

Classical methods for detection of Salmonella involve analysis of faeces or cloacal swabs, or both. However, as classical methods are impractical for large surveys, gauze pad or tampon based drag swabs being the most widely used for flock level detection often require different diluents (e.g. BPW) to collect samples and considerable amount of time (20–30 min./shed) [14,15]. Dust sampling is comparatively easier than drag swabbing and previously been used in a nationwide survey in Japan [16]. In this study Salmonella in enriched dust samples collected using settle plates could-be detected throughout the 22 weeks observation period following experimental infection and vaccination. Another study detected Salmonella in dust samples collected by drag swab samples or scraped dust samples from a caged-layer shed floor and found that Salmonella was constantly detectable in dust over the 26 weeks observation period following oral S. Typhimurium challenge and 3 doses of live Salmonella vaccine [4]. In another study, randomly collected litter materials or soil has been used for the detection of Salmonella in broiler farms [17]. Collection of such samples may under or over-estimate the presence of Salmonella due to the localised nature of these samples. Dust samples represent material dispersed and mixed in the air, and studies with other pathogens have demonstrated that location of settle plates within poultry houses does not influence the level of pathogen detected [18]. In fact, Groves et al. [9] describes that dust samples of the untreated unchallenged group separated by 6 m from the nearest challenged pen were positive at 8.5 and 12 weeks of age when the dust samples of challenged groups were also positive. In that study, drag swab samples were only positive in the control pen when birds were 18-week old, suggesting that testing of settled dust samples provides a useful complementary tool for Salmonella monitoring.

Compared to culture methods, PCR analysis of dust samples can reduce the turn-around time from 4–5 days to 1–2 days [19]. Detection of Salmonella from any given sample by culture prior to PCR analysis may reduce sensitivity [20]. In the present study enrichment of dust sample in BPW for 18 h increased the sensitivity of detection of Salmonella with 25/40 and 16/40 of samples positive for enriched and non-enriched samples respectively. This is consistent with other studies indicating that enrichment in BPW for 18–24 h followed by PCR detection can improve sensitivity of detection in faeces [19], chicken meat [20], feed and water [21], clinical samples [22] and environmental samples [22]. Thomason et al. [23] reported that BPW increased the detection of Salmonella by about 25% in absolute percentage terms from environmental samples. In this study, pre-enrichment of dust in BPW increased the recovery of Salmonella from 40% to 62.5%.

In this study, no difference was observed between pre-enriched samples extracted by boiling method and samples extracted by DNA extraction kit in the Salmonella detection pattern (P=1.00) and CFU count (P=0.94) using real-time PCR. Overall detection rates for Salmonella in dust was 62.5% by either method. The lower limits of detection of Salmonella in this study were 1.00 × 100 copies/reaction for the extraction kit and 4.85 × 100 for the boiling method. These were similar to previous reported detection rates in foodstuff [24,25]. De Medici et al. [11] compared four methods of DNA extraction from poultry samples pre-enriched in a broth media and reported boiling method as the preferred extraction method because of simplicity. Similarly, Sweeney et al. [26] compared three methods of DNA extraction from an automated broth culture system and found that boiling extraction is the most suitable method for real-time qPCR. Moreover, the boiling method was also found suitable in several studies for human faecal and oral microbiome analysis [27,28]. The present study indicates that the boiling method could be used to monitor Salmonella in poultry shed dust using PCR, however, when the quality of extracted DNA is paramount such as for high-throughput sequencing applications, the use of an extraction kit would be more appropriate.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. We thank Sithara Ralapanawe, Alison Pankhurst, Michael Raue, Chake Keerqin and Md Zohorul Islam for their support at different stages of this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.mex.2021.101356.

Contributor Information

Md Ahaduzzaman, Email: zaman.cvasu@gmail.com.

Priscilla F Gerber, Email: pgerber2@une.edu.au.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Cerquetti M.C., Gherardi M.M. Vaccination of chickens with a temperature-sensitive mutant of Salmonella enteritidis. Vaccine. 2000;18(11-12):1140–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desin T.S., Köster W., Potter A.A. Salmonella vaccines in poultry: past, present and future. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2013;12(1):87–96. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dórea F.C. Effect of Salmonella vaccination of breeder chickens on contamination of broiler chicken carcasses in integrated poultry operations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76(23):7820–7825. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01320-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P. Shedding of Salmonella Typhimurium in vaccinated and unvaccinated hens during early lay in field conditions: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1201-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gole V.C. Shedding of Salmonella in single age caged commercial layer flock at an early stage of lay. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014;189:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walkden-Brown S.W. Development, application, and results of routine monitoring of Marek's disease virus in broiler house dust using real-time quantitative PCR. Avian Dis. 2013;57(2s1):544–554. doi: 10.1637/10380-92112-REG.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahaduzzaman M. A practical method for assessing infectious laryngotracheitis vaccine take in broilers following mass administration in water: spatial and temporal variation in viral genome content of poultry dust after vaccination. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;241 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Löfström C. Detection of Salmonella in meat: comparative and interlaboratory validation of a noncomplex and cost-effective pre-PCR protocol. J. AOAC Int. 2012;95(1):100–104. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.11-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groves P.J. Can a combination of vaccination, probiotic and organic acid treatment in layer hens protect against early life exposure to Salmonella Typhimurium and challenge at sexual maturity? Vaccine. 2020;39(5):815–824. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AS 5013.10-2009 Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs: horizontal method for the detection of Salmonella spp. AS 5013.10-2009. DAWE Australian Govt. Dep. Agric. Water Environ. 2020;4(6):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Medici D. Evaluation of DNA extraction methods for use in combination with SYBR green I real-time PCR to detect Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis in poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69(6):3456–3461. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3456-3461.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders E.R. Aseptic laboratory techniques: plating methods. J. Vis. Exp. 2012;(63) doi: 10.3791/3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng C.M. Rapid detection of Salmonella in foods using real-time PCR. J. Food Prot. 2008;71(12):2436–2441. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.12.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavic A., Groves P.J., Cox J.M. Development and validation of a drag swab method using tampons and different diluents for the detection of members of Salmonella in broiler houses. Avian Pathol. 2011;40(6):651–656. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2011.625566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallinson E. Monitoring poultry farms for Salmonella by drag-swab sampling and antigen-capture immunoassay. Avian Dis. 1989:684–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwabuchi E. Nationwide survey of Salmonella prevalence in environmental dust from layer farms in Japan. J. Food Prot. 2010;73(11):1993–2000. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-73.11.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks J. Cultivation and qPCR detection of pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant bacterial establishment in naïve broiler houses. J. Environ. Qual. 2016;45(3):958–966. doi: 10.2134/jeq2015.09.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen T.V. Spatial and temporal variation of Marek's disease virus and infectious laryngotracheitis virus genome in dust samples following live vaccination of layer flocks. Vet. Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sommer D. Salmonella detection in poultry samples. Tierärztl. Prax. Ausg. G Großtiere Nutztiere. 2012;40(06):383–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myint M. The effect of pre-enrichment protocol on the sensitivity and specificity of PCR for detection of naturally contaminated Salmonella in raw poultry compared to conventional culture. Food Microbiol. 2006;23(6):599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nam H.M. Application of SYBR green real-time PCR assay for specific detection of Salmonella spp. in dairy farm environmental samples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005;102(2):161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrank I. Influence of enrichment media and application of a PCR based method to detect Salmonella in poultry industry products and clinical samples. Vet. Microbiol. 2001;82(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(01)00350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomason B.M., Dodd D.J., Cherry W.B. Increased recovery of salmonellae from environmental samples enriched with buffered peptone water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977;34(3):270–273. doi: 10.1128/aem.34.3.270-273.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira A. Validating the Efficiency of a Simplex PCR and Quantitative SYBR Green qPCR for the Identification of Salmonella spp. J. Food Microbiol. Saf. Hyg. 2018;3(130):2476–2059.1000130. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Techathuvanan C., Draughon F.A., D'Souza D.H. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR for the rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella typhimurium from pork. J. Food Prot. 2010;73(3):507–514. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-73.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweeney R.W., Whitlock R.H., McAdams S.C. Comparison of three DNA preparation methods for real-time polymerase chain reaction confirmation of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis growth in an automated broth culture system. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2006;18(6):587–590. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng X. Comparison of direct boiling method with commercial kits for extracting fecal microbiome DNA by Illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA tags. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2013;95(3):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamagishi J. Comparison of boiling and robotics automation method in DNA extraction for metagenomic sequencing of human oral microbes. PLoS One. 2016;11(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.