Key Points

Question

How often are race and ethnicity reported for human study participants in surgical literature, and when race is reported, do authors follow the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommendations for quality reporting?

Findings

In this study of 2485 articles published in 2019, the reporting of race and ethnicity was low at a mean (SD) of 32.5% (12.0) overall. There was no significant difference in the frequency of race and ethnicity reporting in publications from journals that state they follow ICMJE recommendations compared with those that do not explicitly claim adherence, but journals following ICMJE recommendations were more likely to follow the guidelines for quality reporting.

Meaning

Increased frequency and improved standardization of race and ethnicity reporting is needed among publications from surgical journals.

This study assesses the frequency and quality of race reporting among publications from high-ranking broad-focused surgical research journals.

Abstract

Importance

The reporting of race provides transparency to the representativeness of data and helps inform health care disparities. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) developed recommendations to promote quality reporting of race; however, the frequency of reporting continues to be low among most medical journals.

Objective

To assess the frequency as well as quality of race reporting among publications from high-ranking broad-focused surgical research journals.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A literature review and bibliometric analysis was performed examining all human-based primary research articles published in 2019 from 7 surgical journals: JAMA Surgery, Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Annals of Surgery, Surgery, American Journal of Surgery, Journal of Surgical Research, and Journal of Surgical Education. The 5 journals that stated they follow the ICMJE recommendations were analyzed against the 2 journals that did not explicitly claim adherence.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Measured study outcomes included race reporting frequency and use of the ICMJE recommendations for quality reporting of race.

Results

A total of 2485 publications were included in the study. The mean (SD) frequency of reporting of race and ethnicity in publications of ICMJE vs non-ICMJE journals was 32.8% (8.4) and 32.0% (20.9), respectively (P = .72). Adherence to ICMJE recommendations for reporting race was more frequent in ICMJE journals than non-ICMJE journals (mean [SD] of 73.1% [17.8] vs 37.0% [10.2]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The frequency of race and ethnicity reporting among surgical journals is low. A journal’s statement of adherence to ICMJE recommendations did not affect the frequency of race and ethnicity reporting; however, there was an increase in the use of ICMJE quality metrics. These findings suggest the need for increased and more standardized reporting of racial and ethnic demographic data among surgical journals.

Introduction

Inequities affecting underserved racial and ethnic groups continue to be identified across the spectrum of medical research.1,2,3,4 From the disproportionate number of Black and Hispanic persons who have been hospitalized or died because of COVID-19 in 20205,6,7,8 to discrimination against Asian American persons9 and the comparatively poor perioperative outcomes even among low-risk racial and ethnic minority patients,10,11 attentiveness to race and ethnicity has illuminated inequities and disparities throughout our health care systems. Recognition of health disparities through research has led to recent significant victories, such as the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act of 2019,12 which became public law in January 2021, requiring officials to examine barriers to government-funded clinical trials for traditionally underrepresented groups. Unfortunately, race and ethnicity continue to be infrequently reported in the medical literature to describe study participants, and when race is described, the quality of the reporting is variable.1,2,3,4,13,14,15,16

In 1978 (updated in 2019), the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) developed recommendations for uniformity in manuscript submissions and promoting increased frequency and quality reporting of race. Current recommendations are that “[a]uthors should define how they determined race or ethnicity and justify their relevance,”17 and that a study “should aim for inclusion of representative populations into all study types and at a minimum provide descriptive data for these and other relevant demographic variables.”17,18,19 Despite these recommendations, studies examining the reporting of race continue to show infrequent use of race to describe study participants in scientific publications.13,14,15,16 A 2020 article by Moore14 revealed that in the ophthalmology literature, most articles (88%) reported baseline demographic information on study participants; however, only 43% of articles included data on race and ethnicity, and an even smaller fraction described how the information was determined.

There are few current data to describe the quantity or quality of demographic reporting within the surgery literature.16 To provide information on the recent landscape, the aim of this study is to determine the frequency and quality of the reporting of race and ethnicity in primary research publications from high-ranking broad-focused surgical research journals during 2019.

Methods

A list of US-based high-ranking, broad-focused surgical research journals was created for this study based on a review of rankings in Scimago Journal & Country Rank and Scopus Citescore. The 7 journals included were JAMA Surgery, Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS), Annals of Surgery, Surgery, American Journal of Surgery (AJS), Journal of Surgical Research (JSR), and Journal of Surgical Education (JSE). A comprehensive literature search using Medline was performed to catalog all articles that were published by each journal (either online or in print) between January 1 and December 31, 2019. 2019 Was selected as the most recent complete publishing year with the least risk of potential anomalies in the submission process, particularly in respect to the national and global events of 2020. Inclusion criteria included full-length articles written in English and published as peer-reviewed primary research. Exclusion criteria included all non–research-focused articles (such as editorials, commentaries, and letters to the editor), review articles, meta-analyses, case reports, and nonhuman studies. This work is a review and content analysis of existing surgical literature, which is publicly available data and is not subject to institutional review board inspection.

Title and abstract screening were conducted using the set inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two independent investigators (R.C.M. and M.B.) each screened the entire list of cataloged articles, and conflict resolution was performed by a third investigator (E.M.W.) not involved with the initial screening. Of note, 2 of the journals listed during the study period of interest (JSR and JSE) had not publicly stated that they follow the ICMJE recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. The publications included from these journals were separated for subgroup analysis.

With the final list of included articles, a full-text review was conducted for bibliometric analysis. The data collected included (1) whether the authors reported study participant demographic characteristics within the article (eg, age, sex, body mass index), (2) if the race and ethnicity of study participants were reported, (3) how race and ethnicity were classified in the article (“race,” “ethnicity,” “race/ethnicity,” “descent,” “population,” “ancestry,” other, or not classified), and (4) how the race and ethnicity of the study participants was determined (self-report, perception of health care professionals or researchers, parent/caregiver report, National/Government ID, personal/parent birth country, or unspecified [ie, clinical database review, institutional electronic medical record review]). Reporting of quality data was evaluated using recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals as outlined by the ICMJE17 and the American Medical Association Manual of Style.19 More specifically, 5 quality criteria were used to distill if the authors of the article (1) reported who classified the individuals in terms of race and ethnicity, (2) explained why the classification reported in the study was used, (3) indicated whether the classification options were defined by the investigator or the participant, (4) explained why race and ethnicity were assessed in the study, and (5) if the variable of race was defined in the article.

The characteristics of the selected studies were collected in Excel version 2104 (Microsoft). Descriptive statistics were performed for the tallied categorical variables and compared using χ2 and Fisher exact test. All P values were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was set at a P value less than .05. All analysis was performed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

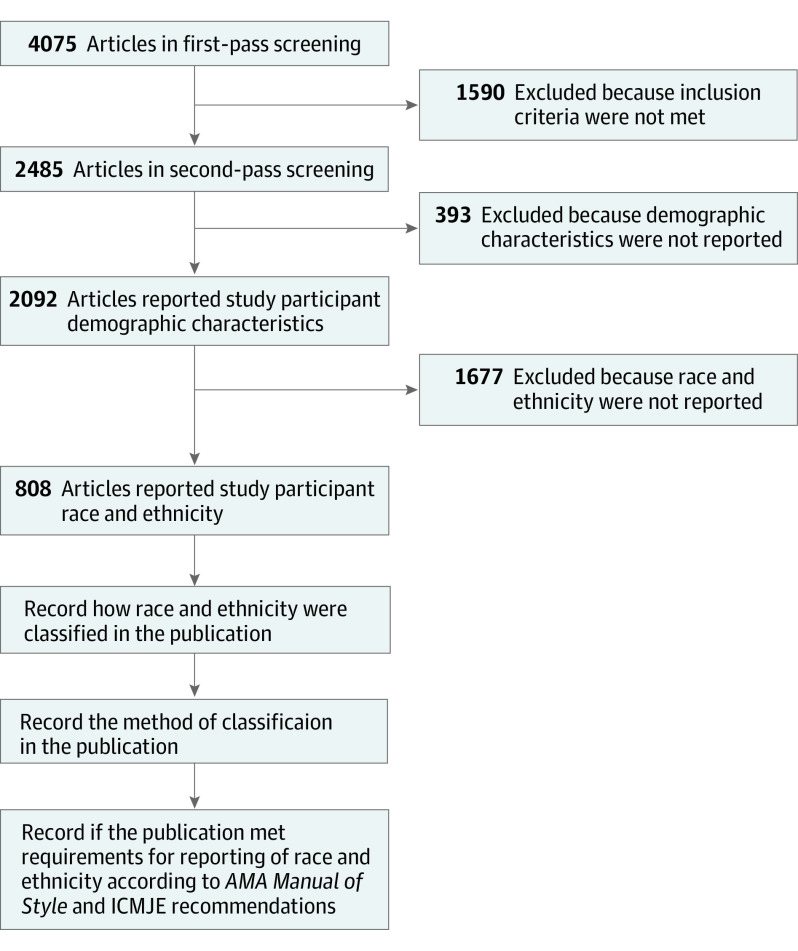

From January 1 to December 31, 2019, there were 4075 total articles published among the 7 surgical journals assessed in this study (Figure 1). Of these, 2485 articles met the inclusion criteria to be further analyzed. Overall, most of the included articles reported some study participant demographic characteristics (2092 of 2485; mean [SD] of 84.2% [16.7]); however, only approximately one-third of articles reported the race or ethnicity of the study participants (808 of 2485; mean [SD] of 32.5% [12.0]). If race was reported, the most common classification used was “race” (466 of 808; mean [SD] of 57.7% [18.8]) followed by “race/ethnicity” (249 of 808; mean [SD] of 30.8% [19.4]). After determining how the classification of individuals was decided, the most common mechanism was unspecified (681 of 808; mean [SD] of 84.3% [17.0]) followed by self-report of the participants (101 of 808; mean [SD] of 12.5% [11.5]).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of the Publication Screening Methodology.

AMA indicates American Medical Association; ICMJE, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Subgroup analysis distributed the analyzed journals into those that stated they are following the ICMJE recommendations and those that have not explicitly stated so (Table 1). There were 1624 articles in the ICMJE group (65.4%) and 861 articles in the non-ICMJE group (34.6%). Most articles both in the ICMJE and non-ICMJE groups reported demographic characteristics (mean [SD] of 87.4% [6.0] vs 78.2% [29.3]; P < .001), while a minority of articles in ICMJE and non-ICMJE groups reported the race or ethnicity of participants (mean [SD] of 32.8% [8.4] vs 32.0% [20.9]; P = .72). The most common classification in both the ICMJE and non-ICMJE groups was “race” (mean [SD] of 56.4% [22.0] vs 60.1% [13.6]; P < .001) followed by “race/ethnicity” (mean [SD] of 33.1% [23.1] vs 26.4% [7.3]; P < .001). The most common mechanism for determining participant classification in both the ICMJE and non-ICMJE groups was unspecified (mean [SD] of 85.7% [6.7] vs 81.5% [30.5]; P < .001), followed by self-report (mean [SD] of 12.6% [6.7] vs 12.3% [21.2]; P < .001).

Table 1. Frequency of Race and Ethnicity Reporting.

| Characteristic | ICMJE (n = 1624) | Non-ICMJE (n = 861) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %, Mean (SD) | No. | %, Mean (SD) | ||

| Demographic characteristics reported | 1419 | 87.4 (6.0) | 673 | 78.2 (29.3) | <.001 |

| Race and ethnicity reported | 532 | 32.8 (8.4) | 276 | 32.0 (20.9) | .72 |

| Classifications reported | |||||

| “Race” | 300 | 56.4 (22.0) | 166 | 60.1 (13.6) | <.001 |

| “Ethnicity” | 25 | 4.7 (2.9) | 15 | 5.4 (1.5) | |

| “Race/ethnicity” | 176 | 33.1 (23.1) | 73 | 26.4 (7.3) | |

| “Descent” | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 (0.3) | |

| “Population” | 0 | 0 | 9 | 3.3 (2.5) | |

| “Ancestry” | 1 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 30 | 5.6 (4.3) | 3 | 1.1 (4.7) | |

| Not classified | 4 | 0.8 (0.8) | 7 | 2.5 (0.8) | |

| Method of classification | |||||

| Self-report | 67 | 12.6 (6.7) | 34 | 12.3 (21.2) | <.001 |

| Perception of health care professionals or researchers | 0 | 0 | 12 | 4.3 (0.6) | |

| Parent/caregiver report | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| National registration identity | 13 | 2.4 (2.7) | 2 | 0.7 (2.2) | |

| Personal or parent birth country | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unspecified | 456 | 85.7 (6.7) | 225 | 81.5 (30.5) | |

Abbreviation: ICMJE, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

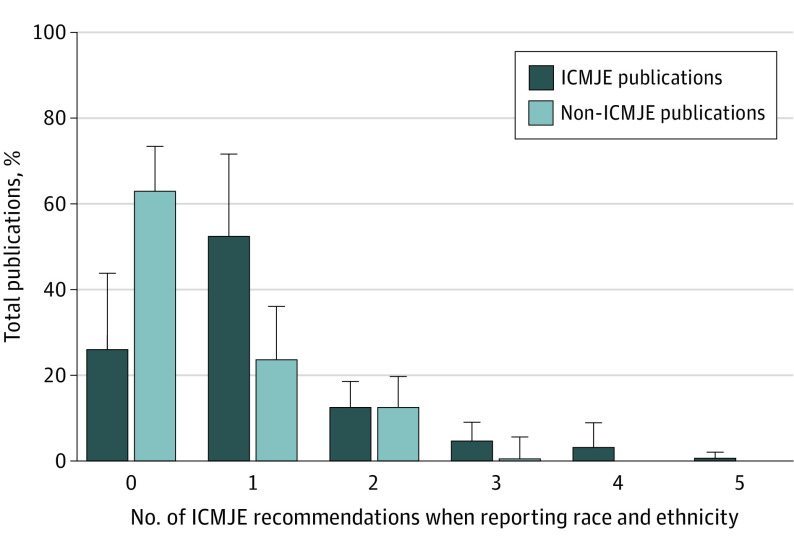

On further analysis of the quality of reporting of race and ethnicity (Table 2), whether the authors reported who classified the individuals in terms of race or ethnicity was not different between the publications from ICMJE and non-ICMJE journals (mean [SD] of 15.4% [6.0] vs 12.3% [21.2]; P = .23). The ICMJE journal publications were more likely to explain why the classification reported in the study was used than non-ICMJE journals (mean [SD] of 11.6% [14.2] vs 9.8% [4.9]; P = .42). ICMJE journal publications were more likely to indicate whether the classification options were defined by the investigator or the participant (mean [SD] of 9.0% [10.5] vs 2.2% [1.1]; P < .001). ICMJE journal publications more often explained why race was assessed in the study (mean [SD] of 69.5% [19.6] vs 26.8% [4.2]; P < .001) and defined the variable of race within the text (mean [SD] of 3.4% [4.2] vs 0%; P < .001). Figure 2 illustrates the proportion of articles published that followed 0 ICMJE recommendations up to all 5 ICMJE recommendations. A mean (SD) of 73.1% (17.8) of articles published in ICMJE journals followed at least 1 recommendation vs 37.0% (10.2) in non-ICMJE journals (P < .001).

Table 2. Frequency of Quality Reporting of Race and Ethnicity Determined by International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations.

| ICMJE recommendation | ICMJE (n = 523) | Non-ICMJE (n = 276) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %, Mean (SD) | No. | %, Mean (SD) | ||

| The authors reported who classified the individuals in terms of race and ethnicity | 82 | 15.4 (6.0) | 34 | 12.3 (21.2) | .23 |

| The authors explained why the classification reported in the study was used | 62 | 11.6 (14.2) | 27 | 9.8 (4.9) | .42 |

| The authors indicated whether the classification options were defined by the investigator or the participant | 48 | 9.0 (10.5) | 6 | 2.2 (1.1) | <.001 |

| The authors explained why race was assessed in the study | 370 | 69.5 (19.6) | 74 | 26.8 (4.2) | <.001 |

| The authors defined the variable of race | 18 | 3.4 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | .002 |

Figure 2. Percentage of Publications Following International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations.

Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Additionally, a separate analysis was performed to compare the frequency and quality of race and ethnicity reporting among prospective vs retrospective studies. Compared with retrospective studies, there was decreased frequency of reporting race in prospective studies (mean of 23.3% vs 43.6%; P < .001) and decreased quality reporting of race in prospective studies (at least 1 ICMJE recommendation used: mean of 58.3% vs 61.5%; P < .001). Lastly, the frequency of studies examining international populations was assessed. There was a total of 183 international articles (7.4%), and of these, 149 (81.4%) reported demographic characteristics, while only 13 (8.7%) reported race and ethnicity.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that while most human-based primary research publications from high-ranking, broad-focused surgical research journals report some level of study participant demographic characteristics, less than one-third reported race or ethnicity. This finding is comparable with investigations of race and ethnicity reporting in journal publications from other medical disciplines.13,14,15,16 When race and ethnicity were reported, the most common classification used was “race,” with a variety of subdivisions among publications (eg, White vs non-White, White vs Black vs “other,” White vs Black vs Asian vs Hispanic). In most studies analyzed, the mechanism used for classification was unspecified. When comparing publications from ICMJE journals with publications from non-ICMJE journals, there was no difference in overall race and ethnicity reporting; however, ICMJE journals were more likely to report overall demographic characteristics and to use “race/ethnicity” as the classification scheme. When comparing the quality of race reporting between ICMJE and non-ICMJE journal publications, there was a significant difference in use of several ICMJE quality recommendations for the reporting of race. Finally, when comparing prospective studies that observe populations over time to a predetermined outcome with retrospective studies, there was an unexpected decrease in both the frequency and quality of race reporting.

We can postulate why race and ethnicity reporting continues to be low in 2019 among surgery publications even with the increasing awareness of health care disparities. Reporting may have been omitted secondary to low representation, lack of data because they were not retrospectively collected, or even failure to see relevance compared with biologically based participant demographic characteristics, such as age or sex. Smaller studies may wish not to include race and ethnicity categories as they can become a potential participant identifier. This is particularly apparent in publications that used qualitative methods or had small sample sizes, as there is a larger potential for participant identification with the inclusion of race and ethnicity. Additionally, many surgery publications studied international populations outside of the US (7.4%). There was an appreciated decrease in the frequency of race and ethnicity reporting, most notably for populations with more homogeneous racial and ethnic compositions. However, authors generally did not acknowledge these limitations or state within their methods a reasoning for the omission of race and ethnicity to describe study participants.

The importance of race and ethnicity reporting in medicine has been studied extensively, as it has significant implications for the generalizability of reported data. Societal guidelines that define standard of medical care are commonly determined based on findings from randomized clinical trials that either do not report participant race or are not nationally representative.20 Breast cancer screening guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force are based on 7 randomized clinical trials, of which none reported race demographic characteristics. Several retrospective database studies have shown that the median age of diagnosis among Black and Hispanic women is almost 10 years lower than White women (57 years, 54 years, and 64 years, respectively), and a greater percentage of women diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50 years are from racial minority groups.21,22 This bolsters the argument that guidelines based on studies that do not report race and ethnicity are likely to miss potentially preventable adverse outcomes. In contrast, the ARCHER 1050 randomized clinical trial23,24 analyzing the efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–targeted therapy for non–small cell lung cancer did report race and ethnicity demographic characteristics among its participants. Although the trial showed no difference in overall survival compared with standard chemotherapy, results of a subgroup analysis examining 346 patients of Asian descent showed improvement in progression-free survival as well as significant improvements in overall survival with use of EGFR-targeted therapy (37.7 months vs 29.1 months; hazard ratio, 0.76).23,24 EGFR variants have been reported in 40% to 50% of lung adenocarcinomas in East Asian individuals but only in 15% of North American and European individuals, suggesting possible regional differences in genetic backgrounds and treatment outcome variability between populations whose ancestry are connected to different parts of the world.25 This trial illustrates the positive impact of reporting of race and ethnicity, as EGFR-targeted therapeutics has become a first-line treatment for specific populations.

This study addressed the quality of race and ethnicity reporting among publications from surgery journals, which was noticeably poor by ICMJE standards. Race is the artificial categorization of humans based on hierarchical justifications and perceptions of shared physical or social qualities, while ethnicity is an individual’s cultural identification.26,27,28,29,30,31,32 Although race and ethnicity have no genetic or biologic basis for categorization, the effect on everyday lived experiences is entirely real. The social, emotional, mental, physical, and geographical implications of this racial myth cannot be ignored. Understanding similar phenotypes and patterns of behavior seen within these socially constructed groupings can help inform medical decision-making in the prevention and management of disease. However, harm is potentially caused when unmeasured genetic or biologic factors are used as the sole reasoning to explain racial or ethnic differences in health outcomes. Historically in the US, research funding has been used to elucidate the genetic determinants of hypertension and heart disease in Black individuals, while the environmental effects of implicit bias and systemic racism have been ignored.33 Guidelines set by the American Medical Association Manual of Style and recommendations from the ICMJE can help lead authors toward appropriate and meaningful reporting of race to enhance the representativeness of the study population. Although increasing the frequency of race reporting in general is a noble goal with clear benefits, we must continue to strive for quality reporting of a complex demographic characterization.

Limitations

An important limitation of our study was the inability to accurately identify how race and ethnicity were determined in studies using clinical databases (eg, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; Trauma Quality Improvement Program; Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; National Cancer Database) and institutional electronic medical record review. If racial and ethnic categories were reported because of the availability of the variable in a clinical database or electronic medical record, it was typically identified by our study methods as unspecified because there was no explicitly described process by which these data were initially retrieved. While it is possible these databases include self-identified designations, they may also have been assigned using some other method (eg, perception of health care professionals or researchers, national registration identifiers). The lack of transparency surrounding how the individual institutions collect race demographic characteristics that feed patient information into these databases made it difficult to fully assess the quality of race and ethnicity reporting for those studies.

Since this study analyzed a single year of research, we cannot yet comment on any yearly temporal changes in reporting race and ethnicity frequency. Because of the significant trends in popular research topic submissions as well as the potential variability of submission frequency from authors secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was decided by our research team to limit our analysis to 2019. Notably, there is still potential for fluctuations to exist within any single-year study (eg, guest editors, theme-focused publications). Examining trends over several years will be important in future research to control for this variation as well as to assess temporal changes in the frequency of race and ethnicity reporting to critically evaluate any applied strategies for improvement.34

Conclusions

In conclusion, these data have demonstrated an overall low frequency and highly varied quality of race and ethnicity reporting among primary research publications from highly ranked, broad-focused surgical research journals in 2019. These data are comparable with studies that have analyzed race reporting in other medical disciplines and adds to the body of literature on this subject. Continued efforts must be made to promote race and ethnicity reporting in surgical research and to standardize the way in which race is reported. Our goal must be to provide transparency of ongoing health care disparities to ourselves and the larger public as well as to hold ourselves accountable to finding solutions.

References

- 1.Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, et al. The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1170-1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb025007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper RS, Nadkarni GN, Ogedegbe G. Race, ancestry, and reporting in medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1531-1532. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(3):482-492.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum K, Grigorian A, Yeates E, et al. A national analysis of pediatric firearm violence and the effects of race and insurance status on risk of mortality. Am J Surg. 2021;S0002-9610(20)30827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karaca-Mandic P, Georgiou A, Sen S. Assessment of COVID-19 hospitalizations by race/ethnicity in 12 states. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(1):131-134. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold JAW, Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, et al. Race, ethnicity, and age trends in persons who died from COVID-19—United States, May-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1517-1521. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collier KT, Rothstein DH. COVID 19: surgery & the question of race. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):845-846. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borno HT, Zhang S, Gomez S. COVID-19 disparities: an urgent call for race reporting and representation in clinical research. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2020;19:100630. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HA, Trinh J, Yang GP. Anti-Asian sentiment in the United States—COVID-19 and history. Am J Surg. 2020;220(3):556-557. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nafiu OO, Mpody C, Kim SS, Uffman JC, Tobias JD. Race, postoperative complications, and death in apparently healthy children. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20194113. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maduka RC, Gibson CE, Chiu AS, et al. Racial disparities in surgical outcomes for benign thyroid disease. Am J Surg. 2020;220(5):1219-1224. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act of 2019, HR 1966, 116th Cong (2019-2020). Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1966

- 13.Bokor-Billmann T, Langan EA, Billmann F. The reporting of race and/or ethnicity in the medical literature: a retrospective bibliometric analysis confirmed room for improvement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;119:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore DB. Reporting of race and ethnicity in the ophthalmology literature in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(8):903-906. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Susarla HK, Dentino KM, Kalenderian E, Ramoni RB. The reporting of race and ethnicity information in the dental public health literature. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(1):21-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao GF, Emlaw J, Chiu AS, et al. Asian American Pacific Islander representation in outcomes research: NSQIP scoping review. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232(5):682-689.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iverson C, Christiansen S, Flanagin A, et al. ; International Committee of Medical Journal Editors . Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. Accessed October 25, 2020. http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf

- 18.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors . Journals stating they follow the ICMJE recommendations. Accessed October 25, 2020. http://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/

- 19.American Medical Association. AMA Manual of Style: A Guide for Authors and Editors. 10th ed. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez NP, Baez YA, Stapleton SM, et al. Racially conscious cancer screening guidelines: a path towards culturally competent science. Ann Surg. Published online May 19, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amirikia KC, Mills P, Bush J, Newman LA. Higher population-based incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer among young African-American women: implications for breast cancer screening recommendations. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2747-2753. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stapleton SM, Oseni TO, Bababekov YJ, Hung YC, Chang DC. Race/ethnicity and age distribution of breast cancer diagnosis in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(6):594-595. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):1454-1466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30608-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mok TSK, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Safety and efficacy of dacomitinib for EGFR+ NSCLC in the subgroup of Asian patients from ARCHER 1050. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 9):ix160–ix161. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz437.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Midha A, Dearden S, McCormack R. EGFR mutation incidence in non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology: a systematic review and global map by ethnicity (mutMapII). Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(9):2892-2911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma IW, Khan NA, Kang A, Zalunardo N, Palepu A. Systematic review identified suboptimal reporting and use of race/ethnicity in general medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(6):572-578. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanawani H, Dame L, Schwartz DA, Cook-Deegan R. Non-reporting and inconsistent reporting of race and ethnicity in articles that claim associations among genotype, outcome, and race or ethnicity. J Med Ethics. 2006;32(12):724-728. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gravlee CC, Sweet E. Race, ethnicity, and racism in medical anthropology, 1977-2002. Med Anthropol Q. 2008;22(1):27-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2008.00002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corbie-Smith G, St George DM, Moody-Ayers S, Ransohoff DF. Adequacy of reporting race/ethnicity in clinical trials in areas of health disparities. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(5):416-420. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanakamedala P, Haga SB. Characterization of clinical study populations by race and ethnicity in biomedical literature. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(1):96-101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drevdahl D, Taylor JY, Phillips DA. Race and ethnicity as variables in nursing research, 1952-2000. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):305-313. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brahan D, Bauchner H. Changes in reporting of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, and age over 10 years. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):e163-e166. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bamshad M, Wooding S, Salisbury BA, Stephens JC. Deconstructing the relationship between genetics and race. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(8):598-609. doi: 10.1038/nrg1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kibbe MR, Freischlag J. Call to action to all surgery journal editors for diversity in the editorial and peer review process. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(11):1015-1016. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]