Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab in individuals with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)?

Findings

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 randomized clinical trial including 90 randomized patients with HS (73 completed the trial), bimekizumab demonstrated clinically meaningful and consistent improvements in participants with HS vs placebo across all assessed outcome measures. Serious adverse events occurred in 2 of 46 bimekizumab-treated participants (4%) and 2 of 21 placebo-treated participants (10%).

Meaning

These initial clinical efficacy and safety data suggest that dual inhibition of interleukin 17A and 17F by bimekizumab may be a viable treatment approach for HS, with the potential to achieve deep responses in clinical outcome measures, and support further evaluation.

This randomized clinical trial assesses whether bimekizumab is efficacious and safe when used to treat patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Abstract

Importance

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease with a high burden for patients and limited existing therapeutic options.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab, a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits interleukin 17A and 17F in individuals with moderate to severe HS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial with an active reference arm was performed from September 22, 2017, to February 21, 2019. The study included a 2- to 4-week screening period, a 12-week treatment period, and a 20-week safety follow-up. Of 167 participants screened at multiple centers, 90 were enrolled. Eligible participants were 18 to 70 years of age with a diagnosis of moderate to severe HS 12 months or more before baseline.

Interventions

Participants with HS were randomized 2:1:1 to receive bimekizumab (640 mg at week 0, 320 mg every 2 weeks), placebo, or reference arm adalimumab (160 mg at week 0, 80 mg at week 2, and 40 mg every week for weeks 4-10).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prespecified primary efficacy variable was the proportion of participants with a 50% or greater reduction from baseline in the total abscess and inflammatory nodule count with no increase in abscess or draining fistula count (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response [HiSCR] at week 12. Exploratory variables included proportion achieving a modified HiSCR with 75% reduction of HiSCR criteria (HiSCR75) or a modified HiSCR with 90% reduction of HiSCR criteria (HiSCR90), change in Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain, and Dermatology Life Quality Index total scores.

Results

Eighty-eight participants received at least 1 dose of study medication (61 [69%] female; median age, 36 years; range, 18-69 years). Seventy-three participants completed the study, including safety follow-up. Bimekizumab demonstrated a higher HiSCR rate vs placebo at week 12 (57.3% vs 26.1%; posterior probability of superiority equaled 0.998, calculated using bayesian analysis). Bimekizumab demonstrated greater clinical improvements compared with placebo. Improvements in the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score (IHS4) were seen at week 12 with bimekizumab (mean [SD] IHS4, 16.0 [18.0]) compared with placebo (mean [SD] IHS4, 40.2 [32.6]). More bimekizumab-treated participants achieved positive results on stringent outcome measures compared with placebo. At week 12, 46% of bimekizumab-treated participants achieved HiSCR75 and 32% achieved HiSCR90, whereas 10% of placebo-treated participants achieved HiSCR75 and none achieved HiSCR90; in adalimumab-treated participants, 35% achieved HiSCR75 and 15% achieved HiSCR90. One participant withdrew because of adverse events. Serious adverse events occurred in 2 of 46 bimekizumab-treated participants (4%), 2 of 21 placebo-treated participants (10%), and 1 of 21 adalimumab-treated participants (5%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial, bimekizumab demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements across all outcome measures, including stringent outcomes. Bimekizumab’s safety profile was consistent with studies of other indications, supporting further evaluation in participants with HS.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03248531

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa (HS) is a chronic, debilitating inflammatory disease,1,2 with a prevalence of 0.03% to 1%1,3 and a mean age at onset of 22 years.4 Patients endure painful, deep-seated, inflammatory nodules and abscesses in sensitive areas of the body, including axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions.1,2 Nodules can rupture and form abscesses and tunnels (sinus tracts), which may require surgical excision.1,2 Extensive scarring and fibrosis can lead to contractures and limb mobility limitations.1,5 Because of the pain, sensitive location, and malodorous discharge, patients’ quality of life is negatively affected and considerable psychological distress occurs.6,7 Comorbidities and complications include arthropathies, metabolic syndrome, increased cardiovascular disease risk, inflammatory disorders, lymphedema, squamous cell carcinoma, and depression.8,9

Despite the relatively high prevalence and severe impact of HS, few treatment options are available.2,5 Adalimumab, an antibody against tumor necrosis factor, is the only biologic therapy currently approved by the European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of moderate to severe HS.10

Interleukin (IL) 17A and IL-17F have been identified as drivers of chronic joint and skin inflammation,11,12,13 share approximately half their structural homology, and have overlapping proinflammatory functions.14,15 The preclinical potential of anti–IL-17A inhibitors translated to success in the treatment of various diseases, including psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.11,12,13,16,17,18 However, many patients respond only partially, or not at all, to inhibition of IL-17A alone. We hypothesize that dual-cytokine blockade may profoundly affect chronic tissue inflammation. Blocking both cytokines may confer additional efficacy in immune-mediated diseases, such as HS, in which IL-17–producing TH cells infiltrate the lesional dermis.19 Bimekizumab is a humanized, full-length IgG monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits both IL-17A and IL-17F and has demonstrated rapid and significant improvements in dermatologic and rheumatologic disease activity.13,20,21

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 study in participants with moderate to severe HS to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of bimekizumab. The novel but well-accepted bayesian augmented control design with placebo and reference arm trial design was chosen because it enables a randomized clinical trial with a smaller sample size while maintaining power. The informative prior is applied to control arms only, reducing the number of participants randomized to receive placebo compared with the active arm.13,22 This method maximizes the number of participants who receive active treatment during the trial, which is particularly important in high-burden diseases, such as HS. The probability of superiority of the active arm compared with placebo is thus determined in place of a statistically significant difference.

Because only 2 randomized controlled trials have been published for treatments in HS and because novel outcome measures were included, adalimumab was administered as an active reference arm to validate the robustness of this study.23,24 Adalimumab was not part of the primary analysis. Following the depth of clinical response demonstrated in bimekizumab trials in psoriasis,17,18,25,26 we also evaluated stringent outcome measures in HS to assess whether a deep response could be achieved in this challenging population.

Methods

Study Design

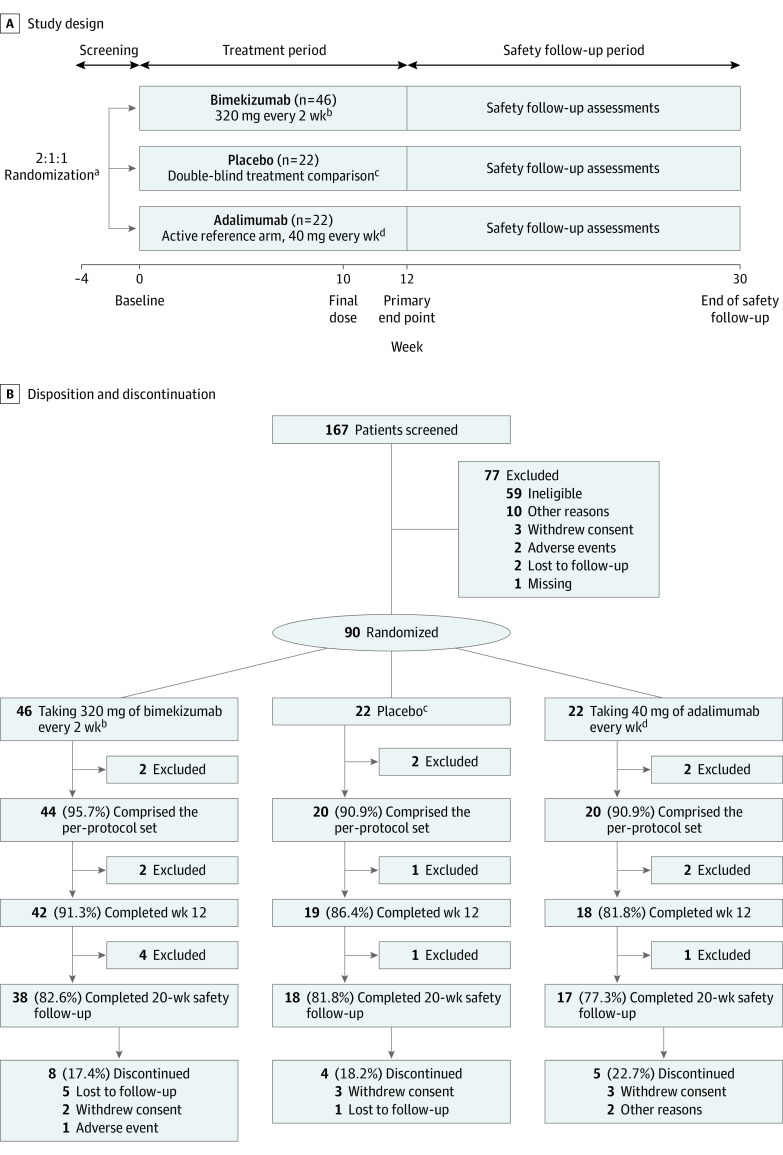

This randomized clinical trial was conducted at sites across North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific regions from September 22, 2017, to February 21, 2019, and included a 2- to 4-week screening, 12-week treatment, and 20-week safety follow-up period after the final treatment dose (Figure 1A). Maximum study duration for any participant was 34 weeks. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki27 and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidance for Good Clinical Practice. Independent institutional review board approvals were obtained from each of the study sites, and all participants provided written informed consent per local requirements. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan can be found in Supplement 1. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Figure 1. Study Design, Disposition, and Discontinuation .

aRandomization was stratified according to Hurley stage at baseline (II or III).

bBimekizumab-treated participants received a loading dose of 640 mg at baseline and then 320 mg every other week from week 2, with a final dose at week 10.

cPlacebo was given at baseline, week 2, and then every week from week 4 to maintain the blinding.

dAdalimumab-treated participants received a loading dose of 160 mg at baseline, 80 mg at week 2, and then 40 mg every week from week 4, with a final dose at week 10. Because of differences in dosing schedule between bimekizumab and adalimumab, placebo injections were administered along with active treatment such that all participants received the same number of injections at each visit. Owing to differences in presentation between bimekizumab and adalimumab, unblinded study personnel prepared and administered the study medication to maintain the blind. The unblinded study personnel did not have any other involvement in the study.

An interactive response technology system was used to assign evaluable participants to a treatment regimen, stratified by baseline Hurley stage. Participants were randomized 2:1:1 to receive 320 mg of bimekizumab every 2 weeks (after a 640-mg loading dose at baseline), placebo weekly from week 4 (with initial doses at baseline and week 2 to maintain blinding), or 40 mg of adalimumab weekly from week 4 (after an initial 160-mg loading dose at baseline and 80 mg at week 2). Placebo injections were administered along with active treatment at weeks 5, 7, and 9 to maintain blinding. Owing to differences in presentation between bimekizumab and adalimumab, unblinded study personnel prepared and administered the study medication with no other involvement in the study. The last dose of study medication was given at week 10.

Participants

Of 167 participants screened, 90 were enrolled and randomized at week 0 to bimekizumab (n = 46), placebo (n = 22), or adalimumab treatment (n = 22) (Figure 1A). Participants were 18 to 70 years of age and had moderate to severe HS diagnosed 12 months or more before baseline. Participants had stable disease at screening and baseline, with lesions in 2 or more distinct anatomical areas (≥1 at Hurley stage II/III), a total abscess and inflammatory nodule (AN) count of 3 or more, and a C-reactive protein level greater than 0.30 mg/dL (to convert to milligrams per liter, multiply by 10). Participants must have had an intolerance, contraindication, or inadequate response to 3 months or more of oral antibiotic treatment for HS or exhibited recurrence after treatment discontinuation. All participants were also candidates for adalimumab treatment per regional labeling.

Key exclusion criteria were a baseline draining tunnel count greater than 20, prior treatment with any anti–IL-17 or anti–tumor necrosis factor, known hypersensitivity to bimekizumab or any of its excipients, diagnosed inflammatory conditions other than HS, and history of chronic or recurrent infections or malignant tumors. Concomitant medications permitted or not permitted during the study and allowed rescue treatments are detailed in eMethods in Supplement 2.

Assessments

The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of participants achieving the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR), defined as a 50% or greater reduction from baseline in the total AN count, with no increase from baseline in abscess or draining fistula (tunnel) count at week 12.28 Exploratory outcome measures that evaluated deeper clinical response included an HiSCR modification to assess the proportion of participants achieving 75% (HiSCR75) and 90% (HiSCR90) improvements from baseline AN count, with no increase from baseline in abscess or draining fistula (tunnel) count. Other efficacy outcomes included the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score (IHS4), a validated and dynamic tool to assess disease severity that consists of a count of the inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and draining fistulae29; Patient’s Global Assessment, an 11-point numeric rating scale for skin pain; and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), which measures quality of life on a scale of 0 to 30, with a total score of 0 to 1 indicating no effect of HS on quality of life. Safety outcomes included incidence, severity, and type of adverse events as well as serious adverse events per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; clinical laboratory measurements and vital signs; electrocardiography; and physical examination. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were defined as adverse events starting at the time of or after the first dose until 140 days after the final dose of study medication. An independent data monitoring committee reviewed safety data on an ongoing basis.

Statistical Analysis

We used a bayesian augmented control design, which allows the borrowing of historical information through informative prior distributions on the control treatment arms, increases the probability that a participant is randomized to active treatment, and provides increased probability of detecting a treatment difference between bimekizumab and placebo. The study was sized to have a large probability of detecting a treatment difference (equivalent to a high power) for the comparison of bimekizumab and placebo; adalimumab was included as a reference arm. Response rates in each arm were modeled using a bayesian logistic regression model with treatment and baseline Hurley stage as factors associated with HiSCR response.

For the primary analysis, placebo and adalimumab used informative priors derived from the PIONEER II (Two Phase 3 Trials of Adalimumab for Hidradenitis Suppurativa) study,24 equivalent to 20 participants each. The informative prior gives specific, definite information about efficacy from previous evidence. The bimekizumab arm used a vague prior (a prior distribution with a large variance because there are few to no prior data published on bimekizumab in HS). The priors and observed data from the per-protocol set were combined and used to derive posterior distributions for the response rate in each treatment arm and a posterior distribution of the treatment difference between bimekizumab and placebo. We randomly and repeatedly drew from the latter posterior distribution to calculate the probability that bimekizumab was superior to placebo. The criterion for declaring superiority was a probability greater than 0.975, as per convention.

The sample size of 60 participants between bimekizumab and placebo provided greater than 90% predictive probability to identify the superior treatment, assuming a response rate of 70% for bimekizumab (β = 5.52) and 28% for placebo (β = 14.48; absolute difference of 42 percentage points). The prior for adalimumab reflected a response rate of 59% (β = 11.78) vs placebo (β = 8.22).

We report response rates in each treatment group with 95% credible intervals. The primary analysis was based on the per-protocol set (excluding participants with protocol deviations affecting the primary end point) and assumes that early treatment discontinuations are nonresponders at week 12. Study participants who received rescue therapy were considered nonresponders from the time that the rescue therapy was taken. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Eighty-eight participants (61 [69%] female; median age, 36 years; range, 18-69 years) received at least 1 dose of study medication and comprised the full analysis and safety set. Discontinuation rates were low and balanced across treatment arms: 79 participants (88%) completed week 12 (the primary end point), and 73 (81%) completed the entire study, including the safety follow-up visit (Figure 1B). Most frequent primary reasons for discontinuation were withdrawal of consent (not because of an adverse event) (8 participants) and unavailable for follow-up (6 participants).

Baseline characteristics were similar across treatment arms, although mean C-reactive protein level and DLQI were numerically higher in the adalimumab group (Table 1). The AN count in the bimekizumab group, although lower than the other treatment arms, was comparable to baseline characteristics of the adalimumab group from the PIONEER I (Two Phase 3 Trials of Adalimumab for Hidradenitis Suppurativa) study.24

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | Bimekizumab (n = 46) | Placebo (n = 21) | Adalimumab (n = 21) | All participants (N = 88)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 37.4 (11.9) | 40.7 (12.8) | 31.1 (9.4) | 36.7 (12.0) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 30 (65) | 14 (67) | 17 (81) | 61 (69) |

| Male | 16 (35) | 7 (33) | 4 (19) | 27 (31) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 34.5 (8.2) | 33.2 (5.8) | 36.9 (10.6) | 34.8 (8.4) |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), y | 9.0 (8.8) | 9.5 (8.4) | 8.6 (5.7) | 9.0 (8.0) |

| hsCRP, mean (SD), mg/dL | 1.53 (1.86) | 1.69 (1.38) | 2.64 (2.50) | 1.83 (1.97) |

| IHS4, mean (SD) | 40.5 (29.8) | 49.8 (34.7) | 42.0 (26.1) | 43.1 (30.1) |

| PtGA of skin pain, mean (SD)c | ||||

| Average in last 24 h | 3.7 (2.4) (n = 46) | 4.0 (2.5) (n = 20) | 5.0 (2.6) (n = 21) | 4.1 (2.5) (n = 87) |

| Worst in last 24 h | 4.7 (2.8) (n = 46) | 5.6 (2.7) (n = 20) | 5.8 (2.7) (n = 21) | 5.2 (2.8) (n = 87) |

| Hurley stage | ||||

| II | 23 (50) | 10 (48) | 10 (48) | 43 (49) |

| III | 23 (50) | 11 (52) | 11 (52) | 45 (51) |

| DLQI, Mean (SD) | 11.7 (8.0) | 12.7 (5.7) | 14.5 (7.9) | 12.6 (7.5) |

| AN count, mean (SD) | 14.5 (11.9) | 22.1 (21.2) | 20.0 (11.5) | 17.7 (14.8) |

| HS-PGA, very severed | 28 (61) | 15 (71) | 12 (57) | 55 (63) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 6 (13.0) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | 12 (13.6) |

| Arthralgia | 2 (4.3) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 4 (4.5) |

| Arthritis | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Hypermobility syndrome | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Osteoarthritis | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Osteochondrosis | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.1) |

| Spondylitis | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Spondylolisthesis | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: AN, abscess and inflammatory nodule; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HS-PGA, Hidradenitis Suppurativa Physician’s Global Assessment; IHS4, International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score; PtGA, Patient’s Global Assessment.

SI conversion factor: To convert hsCRP to milligrams per liter, multiply by 10.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Full analysis set except for age, sex, BMI, and prior history of musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, which constitute the safety set; there were no differences in participant numbers between the safety set and full analysis sets.

Eleven-point numeric rating scale.

Six-point scale from clear to very severe.

Efficacy

The primary analysis compared week 12 HiSCR between the bimekizumab and placebo arms using a bayesian analysis and the per-protocol set. The modeled HiSCR was 57.3% in the bimekizumab group and 26.1% in the placebo group (95% credible interval for difference, 11.0%-50.4%; posterior probability of superiority = 0.998) (Figure 2A). The observed data and informative prior used for the placebo arm exhibited a high degree of concordance (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Primary Analysis.

Bayesian analysis was performed in which the posterior probability distribution for the difference in the primary end point (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response [HiSCR] at 12 weeks) between bimekizumab-treated and placebo-treated participants confirmed that the superiority criteria for bimekizumab were met. NRI indicates nonresponder imputation.

Primary analysis results were confirmed in the full analysis set (eTable 1 in Supplement 2) and using vague priors for bimekizumab and placebo (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 2). A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding participants who were unavailable for follow-up (eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 2).

A frequentist (nonbayesian) sensitivity analysis of observed data explored the odds ratio of response between bimekizumab or adalimumab and placebo (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2) and indicated superiority of bimekizumab and adalimumab to placebo by HiSCR. Numerically higher HiSCR rates were observed from weeks 2 to 12 with bimekizumab compared with placebo (nonresponder imputation at week 12: bimekizumab, 57%; placebo, 24%), similar to adalimumab (60%) (Figure 2B; eTable 6 in Supplement 2). For comparison of response between bimekizumab and adalimumab, the 95% CI did not exclude 1.

More stringent exploratory outcomes showed that numerically higher proportions of participants treated with bimekizumab than placebo achieved HiSCR75 and HiSCR90 beginning at week 2 and at each visit through week 12 (Figure 2C and 2D). At week 12, 46% of bimekizumab-treated participants achieved HiSCR75 and 32% achieved HiSCR90, whereas 10% of placebo-treated participants achieved HiSCR75 and none achieved HiSCR90; in adalimumab-treated participants, 35% achieved HiSCR75 and 15% achieved HiSCR90.

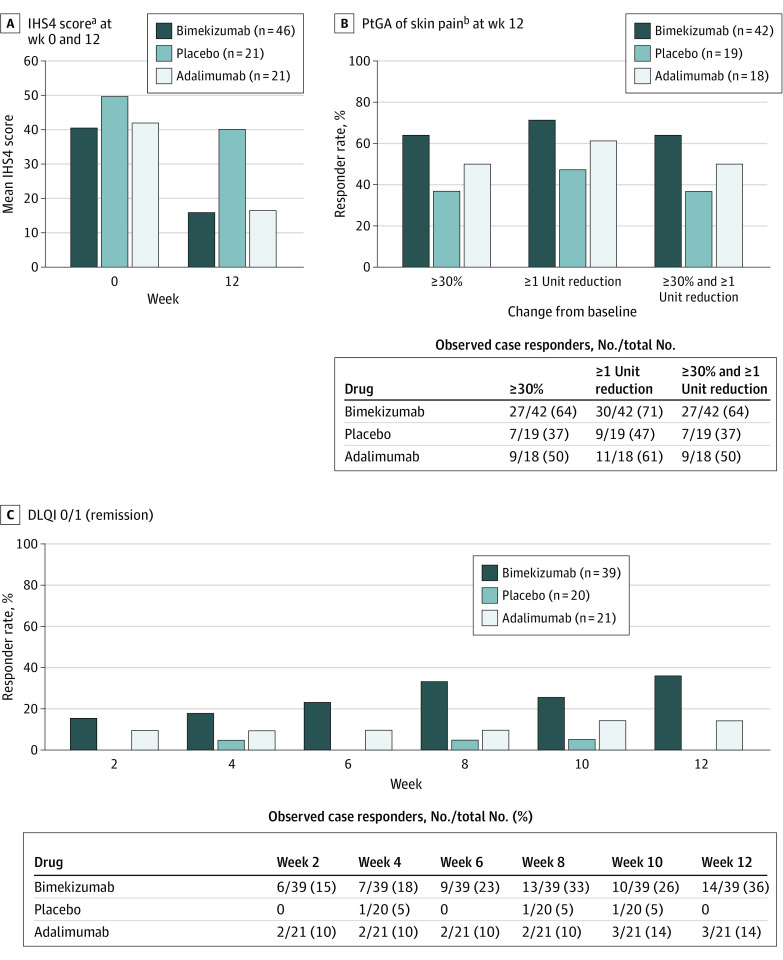

Improvements in IHS4 were seen at week 12 with bimekizumab (mean [SD] IHS4, 16.0 [18.0]) compared with placebo (mean [SD] IHS4, 40.2 [32.6]) (Figure 3A). Higher proportions of bimekizumab-treated participants also reported greater improvements in skin pain at week 12 (Figure 3B) and no impact of disease on their quality of life compared with placebo-treated participants (DLQI 0/1 responder rate, 36% in bimekizumab-treated participants and 0% in placebo-treated participants) (Figure 3C). In adalimumab-treated participants, improvements in IHS4 (week 12: 16.5), skin pain (≥30% and ≥1-unit reduction at week 12: 50%), and DLQI 0/1 (remission at week 12: 14%) were numerically similar or smaller than those treated with bimekizumab (mean IHS4 at week 12: 16.0; ≥30% and ≥1-unit reduction at week 12: 64%; remission at week 12: 36%) (Figure 3). Pharmacokinetic findings for bimekizumab are given in the eResults in Supplement 2.

Figure 3. International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score (IHS4), Patient’s Global Assessment of Pain (PtGA), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) Scores in the Full Analysis Set (Observed Data).

aIHS4 = (number of inflammatory nodules ×1) + (number of abscesses ×2) + (number of draining fistulae ×4).

bMean PtGA of skin pain judged as pain at its worst in the last 24 hours (before week 12 visit) using an 11-point numeric rating scale.

Safety

Incidence of TEAEs was similar across treatment arms (bimekizumab, 70%; placebo, 62%; and adalimumab, 71%) (Table 2). Most were mild or moderate, and only 1 participant (in the bimekizumab group) discontinued study participation because of a TEAE (worsening HS). Hospitalization occurred for the following adverse events: anemia and empyema (bimekizumab-treated patients); hidradenitis (adalimumab-treated patients); and myocardial infarction, hypoesthesia, headache, and dizziness (placebo-treated patients). No deaths occurred.

Table 2. Safety Outcomes.

| Safety outcome | No. (%) of participants with at least 1 TEAE [No. of events] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bimekizumab (n = 46) | Placebo (n = 21) | Adalimumab (n = 21) | |

| Any TEAE | 32 (70) [150] | 13 (62) [30] | 15 (71) [60] |

| Serious TEAEs | 2 (4) [2] | 2 (10) [4] | 1 (5) [2] |

| Anemia | 1 (2) [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (5) [1] | 0 |

| Empyema | 1 (2) [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 1 (5) [1] | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 (5) [1] | 0 |

| Hypoesthesia | 0 | 1 (5) [1] | 0 |

| Hidradenitisa | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) [2] |

| Discontinuation because of TEAE | 1 (2) [1] | 0 | 0 |

| Drug-related TEAEs | 18 (39) [48] | 3 (14) [4] | 9 (43) [29] |

| Severe TEAEs | 3 (7) [6] | 1 (5) [2] | 2 (10) [2] |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most common TEAEs and those of interestb | |||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 8 (17) [15] | 3 (14) [3] | 3 (14) [7] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 10 (22) [20] | 2 (10) [3] | 5 (24) [11] |

| Infections and infestations | 20 (44) [41] | 4 (19) [4] | 9 (43) [19] |

| Oral candidiasis | 3 (7) [4] | 0 | 1 (5) [1] |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | 1 (2) [3] | 0 | 1 (5) [3] |

| Skin candida | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) [1] |

| Influenza | 0 | 0 | 3 (14) [3] |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 5 (11) [10] | 2 (10) [2] | 2 (10) [2] |

| Nervous system disorders | 5 (11) [6] | 6 (29) [9] | 2 (10) [2] |

| Headache | 3 (7) [4] | 3 (14) [5] | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous disorders | 13 (28) [22] | 4 (19) [4] | 9 (43) [12] |

| Hidradenitisa | 8 (17) [9] | 3 (14) [3] | 7 (33) [8] |

| Vascular disorders | 6 (13) [6] | 0 | 1 (5) [1] |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Signs or symptoms of the condition or disease for which the investigational medicinal product is being studied (hidradenitis) were recorded as adverse events only if their nature changed considerably or their frequency or intensity increased in a clinically significant manner compared with the clinical profile known to the investigator from the subject’s history or the baseline period.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in more than 10% of participants in any treatment group by MedDRA version 19.0 system organ class or preferred term are given, unless otherwise specified.

The most frequent TEAEs at the system organ class level in the bimekizumab and adalimumab arms were infections or infestations, skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders, and general disorders or administration site conditions. At the preferred term level, the only TEAEs that occurred in more than 10% of participants in any treatment group were influenza, headache, and hidradenitis (Table 2).

The incidence of serious TEAEs was low and similar across treatment arms, and none were considered related or led to discontinuation (Table 2). The incidence of severe TEAEs was also low and similar across treatment arms. Four nonserious oral candidiasis events were observed in 3 of 46 participants in the bimekizumab group, 1 event occurred in the adalimumab group, and none in the placebo group. All cases of candidiasis with bimekizumab were localized, mild or moderate infections and resolved with appropriate antifungal therapy; no cases led to discontinuation. No instances of inflammatory bowel disease or suicidal ideation or behavior occurred in any group.

From weeks 0 to 12, a total of 5% of participants reported the use of any rescue medication (2 bimekizumab treated, 1 placebo treated, and 1 adalimumab treated). Rescue medications from baseline to safety follow-up are detailed in eTable 7 in Supplement 2.

Overall, there were no unexpected safety findings. The initial safety profile in HS was consistent with bimekizumab trials for other indications under development, such as psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondylarthritis.

Discussion

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial, bimekizumab demonstrated clinically meaningful and consistent improvements vs placebo across all assessed outcome measures, from as early as week 2 through week 12, in participants with moderate to severe HS. To our knowledge, this is the first controlled study in HS to include 2 distinct mechanisms of action, with the inclusion of adalimumab as an indirect reference to validate the accuracy of the incremental benefit from bimekizumab vs placebo.

Increased levels of IL-17 have been identified in the serum and lesions of patients with HS,19,30,31,32 and case reports describe successful treatment of severe HS with IL-17A therapies,33 although randomized, placebo-controlled evidence is lacking. IL-17A and IL-17F have been identified as key drivers of chronic human tissue inflammation produced from innatelike lymphocytes, such as γΔ T cells.11,12,13 These cytokines can be secreted as homodimers or heterodimers, both signaling through the IL-17RA/RC receptor complex, making dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F a potential treatment opportunity.

This novel mechanism of action of bimekizumab has increased expectations of treatment outcomes in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis to 90% and beyond. In a recent phase 2b study in patients with psoriatic arthritis, bimekizumab led to complete skin clearance as measured by a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index of 100 for 50% of participants at week 12 and 61% by week 48.16 Similarly, in phase 3 studies in psoriasis, complete skin clearance was achieved by 59% to 68% of participants after 16 weeks of bimekizumab treatment,17,18,25,26 supporting the concept that IL-17A and IL-17F inhibition can result in deep responses.

These promising outcomes led us to investigate the depth of response that could be achieved in the population with HS. In the PIONEER I and II phase 3 studies of adalimumab in HS, 41.8% of participants in PIONEER 1 and 58.9% in PIONEER 2 achieved HiSCR after 12 weeks of treatment.24 In the current study, 57% of the bimekizumab group achieved HiSCR. Although validated,24,28 HiSCR requires only a minimum 50% improvement from baseline AN count without an increase in chronic lesions. Using the more stringent outcomes of HiSCR75 and HiSCR90, which have not previously been assessed in clinical trials, we found that nearly half of bimekizumab-treated participants achieved a 75% improvement and a third achieved a 90% improvement from baseline AN count, and no increase occurred in chronic lesions. Our data provide preliminary evidence that bimekizumab has the potential for greater lesion clearance and thereby benefit to participants.

Previous clinical studies34,35,36,37 of adalimumab in HS have indicated the need for higher induction and maintenance dosing compared with psoriasis, consistent with the higher inflammatory burden in HS. In this study, circulating drug levels of bimekizumab were lower than expected based on pharmacokinetic properties in other populations, supporting the use of higher doses of bimekizumab compared with other immune and inflammatory diseases.

The safety profile of bimekizumab at this early stage of development (at a dose of 320 mg every 2 weeks) appears consistent with bimekizumab to date in other indications under evaluation.13,20,21 The TEAE rates were similar in the bimekizumab, placebo, and adalimumab arms and were mostly mild or moderate in intensity and resolved. As reported with other therapies that target the IL-17 pathway,38,39 participants in the bimekizumab group experienced oral candidiasis infections during the treatment period. All cases of candidiasis with bimekizumab were localized mild or moderate infections and resolved with appropriate antifungal therapy; no cases led to discontinuation. Although HS is associated with inflammatory bowel disease,40,41 there were no incidences of inflammatory bowel disease during the study period. The safety profile of bimekizumab in HS, in particular for the risk of Candida infections, needs to be evaluated in longer-term studies.

Limitations

This study has limitations, including potential biases that may have been introduced by a lack of site-stratified treatment assignments (because of the small sample size, stratification by Hurley stage was prioritized). Differences in demographic characteristics and disease severity among sites might bias efficacy findings. The placebo-treated group had a numerically higher baseline AN count compared with the bimekizumab and adalimumab groups. Although a limitation, the baseline AN count for bimekizumab-treated participants in this study was consistent with those for participants in the PIONEER I and II studies.24

Conclusions

These data suggest that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F by bimekizumab may be a viable treatment approach for HS, with the potential to achieve deep responses in clinical outcomes. Although data are encouraging, the sample size was limited, and longer studies are needed to understand response durability. Further dose regimen elucidation is required because only a single dose regimen was studied. The inflammatory burden of the disease and current pharmacologic treatment outcomes suggest that an intensive dosing regimen (ie, dose level and/or frequency) may be needed for optimal treatment.35 The efficacy and safety findings in this study warrant confirmation with larger phase 3 studies.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eResults. Supplementary Results

eTable 1. Additional Bayesian Analyses of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Informative Prior Distributions and NRI (FAS)

eTable 2. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Vague Prior Distributions and NRI (PPS)

eTable 3. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Vague Prior Distributions and NRI (FAS)

eTable 4. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Informative Prior Distributions and Observed Cases Only (PPS)

eTable 5. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Informative Prior Distributions and Observed Cases Only (FAS)

eTable 6. Observed Case Responders (PPS)

eTable 7. Rescue Medication From Week 0–30 (Through Safety Follow-up)

eFigure 1. Probability Density Functions for HiSCR Response in Primary Analysis for Placebo

eFigure 2. Observed Cases Frequentist Analysis (FAS)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Jemec GB. Clinical practice: hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):158-164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1014163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):619-644. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirsten N, Petersen J, Hagenström K, Augustin M. Epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa in Germany—an observational cohort study based on a multisource approach. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):174-179. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14(5):389-392. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danby FW, Margesson LJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(4):779-793. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chernyshov PV, Zouboulis CC, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. Quality of life measurement in hidradenitis suppurativa: position statement of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology task forces on Quality of Life and Patient-Oriented Outcomes and Acne, Rosacea and Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(9):1633-1643. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, Jemec GBE, Egeberg A. Increased suicide risk in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(1):52-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC. Review of comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa: implications for daily clinical practice. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):63-71. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00354-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC. Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Dermatoendocrinol. 2010;2(1):9-16. doi: 10.4161/derm.2.1.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zouboulis CC. Adalimumab for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(10):1015-1026. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1221762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durham LE, Kirkham BW, Taams LS. Contribution of the IL-17 pathway to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(8):55. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0529-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raychaudhuri SP, Raychaudhuri SK. Mechanistic rationales for targeting interleukin-17A in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1249-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glatt S, Baeten D, Baker T, et al. Dual IL-17A and IL-17F neutralisation by bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: evidence from preclinical experiments and a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial that IL-17F contributes to human chronic tissue inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):523-532. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hymowitz SG, Filvaroff EH, Yin JP, et al. IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO J. 2001;20(19):5332-5341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang XO, Chang SH, Park H, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by IL-17F. J Exp Med. 2008;205(5):1063-1075. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritchlin CT, Kavanaugh A, Merola JF, et al. Bimekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a 48-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):427-440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33161-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(2):142-152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Bagel J, et al. Bimekizumab versus adalimumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(2):130-141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, Hunger RE. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(4):790-798. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glatt S, Helmer E, Haier B, et al. First-in-human randomized study of bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody and selective dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F, in mild psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(5):991-1001. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papp KA, Merola JF, Gottlieb AB, et al. Dual neutralization of both interleukin 17A and interleukin 17F with bimekizumab in patients with psoriasis: results from BE ABLE 1, a 12-week randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(2):277-286.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baeten D, Baraliakos X, Braun J, et al. Anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9906):1705-1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendricks AJ, Hsiao JL, Lowes MA, Shi VY. A comparison of international management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2019;1-16. doi: 10.1159/000503605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):422-434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):475-486. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Bimekizumab Versus Ustekinumab for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis (BE VIVID): efficacy and safety from a 52-week, multicentre, double-blind, active comparator and placebo controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):487-498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00125-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.28105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimball AB, Sobell JM, Zouboulis CC, et al. HiSCR (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response): a novel clinical endpoint to evaluate therapeutic outcomes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from the placebo-controlled portion of a phase 2 adalimumab study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(6):989-994. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zouboulis CC, Tzellos T, Kyrgidis A, et al. ; European Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation Investigator Group . Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1401-1409. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matusiak Ł, Szczęch J, Bieniek A, Nowicka-Suszko D, Szepietowski JC. Increased interleukin (IL)-17 serum levels in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: implications for treatment with anti-IL-17 agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(4):670-675. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of inflammatory cytokine associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2018;7:1930. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.17267.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witte-Händel E, Wolk K, Tsaousi A, et al. The IL-1 pathway is hyperactive in hidradenitis suppurativa and contributes to skin infiltration and destruction. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(6):1294-1305. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuch A, Fischer T, Boehner A, Biedermann T, Volz T. Successful treatment of severe recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa with the interleukin-17A antibody secukinumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(1):151-152. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimball AB, Kerdel F, Adams D, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):846-855. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zouboulis CC, Hansen H, Caposiena Caro RD, et al. Adalimumab dose intensification in recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Dermatology. 2020;236(1):25-30. doi: 10.1159/000503606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riis PT, Søeby K, Saunte DM, Jemec GB. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa carry a higher systemic inflammatory load than other dermatological patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307(10):885-889. doi: 10.1007/s00403-015-1596-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martorell A, García-Martínez FJ, Jiménez-Gallo D, et al. An update on hidradenitis suppurativa (part I): epidemiology, clinical aspects, and definition of disease severity. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(9):703-715. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langley RG, Kimball AB, Nak H, et al. Long-term safety profile of ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: an integrated analysis from 11 clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(2):333-339. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Kerkhof PCM, Griffiths CEM, Reich K, et al. Secukinumab long-term safety experience: a pooled analysis of 10 phase II and III clinical studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):83-98.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egeberg A, Jemec GBE, Kimball AB, et al. Prevalence and risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(5):1060-1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phan K, Tatian A, Woods J, Cains G, Frew JW. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): systematic review and adjusted meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(2):221-228. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eResults. Supplementary Results

eTable 1. Additional Bayesian Analyses of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Informative Prior Distributions and NRI (FAS)

eTable 2. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Vague Prior Distributions and NRI (PPS)

eTable 3. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Vague Prior Distributions and NRI (FAS)

eTable 4. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Informative Prior Distributions and Observed Cases Only (PPS)

eTable 5. Bayesian Analysis of HiSCR at Week 12 Using Informative Prior Distributions and Observed Cases Only (FAS)

eTable 6. Observed Case Responders (PPS)

eTable 7. Rescue Medication From Week 0–30 (Through Safety Follow-up)

eFigure 1. Probability Density Functions for HiSCR Response in Primary Analysis for Placebo

eFigure 2. Observed Cases Frequentist Analysis (FAS)

Data Sharing Statement