Abstract

Patients with COVID-19 are at higher risk of thrombosis due to the inflammatory nature of their disease. A higher-intensity approach to pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis may be warranted. The objective of this retrospective cohort study was to determine if a patient specific, targeted-intensity pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis protocol incorporating severity of illness, weight, and biomarkers decreased incidence of thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Included patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 and received thromboprophylaxis within 48 h of admission. Exclusion criteria included receipt of therapeutic anticoagulation prior to or within 24 h of admission, history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, pregnancy, or incarceration. Per-protocol patients received thromboprophylaxis according to institutional protocol involving escalated doses of anticoagulants based upon severity of illness, total body weight, and biomarker thresholds. The primary outcome was thrombosis. Secondary outcomes included major bleeding, mortality, and identification of risk factors for thrombosis. Of 1189 patients screened, 803 were included in the final analysis. The median age was 54 (42–65) and 446 (55.5%) were male. Patients in the per-protocol group experienced significantly fewer thrombotic events (4.4% vs. 10.7%, p = 0.002), less major bleeding (3.1% vs. 9.6%, p < 0.001), and lower mortality (6.3% vs. 11.8%, p = 0.02) when compared to patients treated off-protocol. Significant predictors of thrombosis included mechanical ventilation and male sex. Post-hoc regression analysis identified mechanical ventilation, major bleeding, and D-dimer ≥ 1500 ng/mL FEU as significant predictors of mortality. A targeted pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis protocol incorporating severity of illness, body weight, and biomarkers appears effective and safe for preventing thrombosis in patients with COVID-19.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11239-021-02552-x.

Keywords: COVID-19, Thromboprophylaxis, Venous thromboembolism, Arterial thrombosis

Highlights

Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are at an increased risk of thrombosis due to the inflammatory nature of their disease.

A pharmacologic prophylaxis protocol incorporating severity of illness, weight, and biomarkers was associated with decreased thrombosis rate (4.4% vs. 10.7%, p = 0.002) and protection against major bleeding (3.1% vs. 9.6%, p < 0.001).

A targeted approach to escalated thromboprophylaxis regimens appears to effectively and safely decrease thrombosis in both critically ill and ward patients with COVID-19.

Background

Patients infected with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), also known as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), experience a disease-dependent risk of coagulopathy and thrombosis alongside severe respiratory symptoms. This presents as localized thrombosis in the lung as well as systemic thrombosis [1–10]. Support for the role of pulmonary microthrombosis in the progression of disease comes from data showing that pulmonary embolism (PE) has occurred more often than deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [1, 2, 4, 9, 11, 12].

Given the current understanding of the role of thromboinflammation in the progression of disease, identifying the optimal dosing approach for prophylactic anticoagulation in COVID-19 is paramount. Factors used to empirically escalate anticoagulant doses include patient weight, as well as severity of illness. Markers of coagulation and coagulopathy, including D-dimer and thromboelastography (TEG) max amplitude, may also be useful to guide therapy in patients with COVID-19 [13–18]. Data on higher-intensity thromboprophylaxis regimens are currently sparse with mixed results. An escalated approach (e.g., enoxaparin 40–60 mg twice daily, enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg twice daily, unfractionated heparin (UFH) 7500 units three times daily) was associated with decreased mortality in two recent retrospective studies [14, 19]. The only randomized controlled trial to date demonstrated no benefit in thrombosis or mortality with enoxaparin 1 mg/kg daily versus enoxaparin 40 mg daily [20]. Additionally, empiric full strength or high-intensity anticoagulation may decrease mortality [9, 21, 22]. Guidelines and consensus statements currently recommend the use of chemoprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 [23–28], although the ideal regimen remains unclear. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of a patient specific, targeted-intensity thromboprophylaxis protocol in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Methods

This retrospective, single center, cohort study was conducted at the University of Colorado Hospital, a large academic medical center, in accordance with the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Patient inclusion and exclusion

Patients admitted with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR between March 1, 2020 and October 31, 2020 were evaluated for inclusion. Included patients additionally had to be initiated on thromboprophylaxis within 48 h of admission. Exclusion criteria included a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), pregnancy or breastfeeding, and incarceration. Patients were also excluded if they received therapeutic anticoagulation prior to admission or within 24 h of admission in order to limit alternative indications (i.e., atrial fibrillation) or probability that patients had an existing thrombus on admission.

Data collection and definitions

All data were extracted through manual chart review from the electronic health record at the University of Colorado Hospital. The following data points were collected from admission information and laboratory values: age, sex, weight, body mass index, creatinine clearance, serum creatinine, hemoglobin, platelets, D-dimer, max amplitude on TEG, and admission unit. Comorbidities were a known component of the patient’s past medical history. In-hospital problems as well as anti-platelet use included an event or administration that may have occurred at anytime and for any duration during the patient’s admission. Of the patients receiving a P2Y12 inhibitor, 1 received prasugrel and 17 received clopidogrel. Acute kidney injury was classified by the AKIN criteria [29]. Renal replacement therapy included both intermittent hemodialysis and/or continuous renal replacement therapy. The PaO2:FiO2 ratio documented was the lowest value recorded during admission.

Intervention

A pharmacologic prophylaxis protocol was implemented for all patients admitted to the University of Colorado Hospital with a diagnosis of COVID-19 (Supplementary Table 1). This protocol was developed through an iterative consensus process involving institutional practitioners and anticoagulation specialists, incorporating severity of illness, total body weight, biomarker data, and available anti-factor Xa measurements from hospitalized COVID-19 patients admitted primarily to the ICU. For this study, patients were stratified into a per-protocol study group if initiated on the appropriate prophylactic regimen within 4 days of admission or an off-protocol study group if initiated on a regimen alternative to the protocol. Briefly, the protocol included a patient specific approach to thromboprophylaxis. Standard doses of prophylaxis could be recommended initially, but dosing was escalated based on patient-specific factors. The institutional protocol dosing recommendations were unchanged throughout the entirety of this evaluation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was incidence of thrombosis, including both venous and arterial clot formation. Key secondary outcomes included major bleeding per the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria [30], all-cause mortality, and identification of risk factors for thrombosis. Additional secondary outcomes included interruption in thromboprophylaxis, change or escalation of thromboprophylaxis, and time from initiation of prophylaxis to thrombosis. Pre-specified subgroup analyses for the primary outcome were also performed. Deep vein thrombosis and acute peripheral arterial thrombosis were identified via duplex ultrasound imaging. Pulmonary embolism was identified via computed topography angiogram. Ischemic stroke was diagnosed via signs and symptoms of stroke according to the NIH stroke scale [31, 32] and supported by computed topography imaging of the head. Myocardial infarction was identified via percutaneous coronary intervention in the catheterization laboratory.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 800 was required to achieve 90% power at a significance of 0.05 to detect a 32% relative risk reduction in thrombosis based on an estimated 31% thrombosis rate [1]. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic and outcomes data. Categorical data were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous data were analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank Sum. A backward stepwise logistic regression was used to determine significant risk factors for thrombosis, and a similar post-hoc regression analysis was used to identify risk factors for mortality. Variables with p-value < 0.2 on univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in each model. A p-value of < 0.05 was used to define statistical significance for all analyses. JMP® Pro version 15.0 was used for all statistical tests.

Results

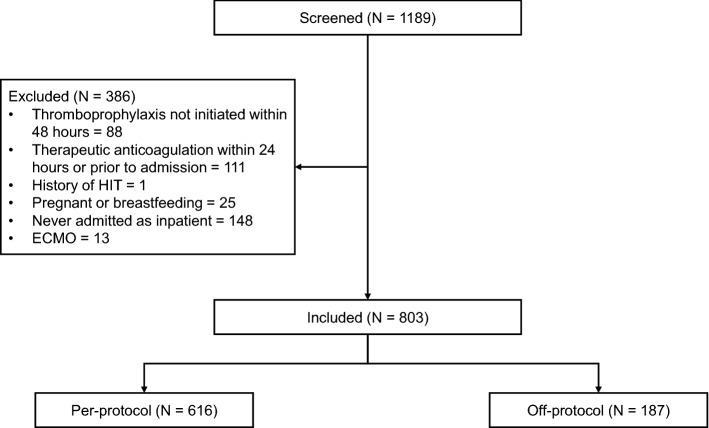

A total of 1189 patients were screened for inclusion over an 8 month time period. Of these patients, 803 were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The median age was 54 (42–65), 446 (55.5%) were male, and 561 (69.9%) were admitted after protocol implementation. In addition, 63.1% of patients included were initiated on standard doses of thromboprophylaxis for medically ill patients (enoxaparin 40 mg daily, UFH 5000 units three times daily). Patients in the off-protocol group were more often male and had larger total body weight, decreased creatinine clearance, and higher D-dimer on admission. The off-protocol patients were also more likely to be admitted prior to protocol implementation, admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), require renal replacement therapy (RRT), mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support, and be initiated on UFH (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient screening and inclusion

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Variable | Per-protocol (n = 616) | Off-protocol (n = 187) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54 (42–65) | 56 (44–66) | 0.12 |

| Male | 324 (52.6) | 122 (65.2) | 0.003 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.5 (69.9–95.3) | 84.8 (72.6–107.9) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 (25.4–33.9) | 31.1 (26.6–37.3) | 0.006 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| CrCl (mL/min) | 98.4 (68.7–127.3) | 83.1 (54.2–115.2) | < 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (g/dL) | 0.81 (0.66–1.01) | 0.99 (0.76–1.29) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.1 (12.7–15.2) | 13.9 (12.5–15.2) | 0.52 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 206 (164–266) | 199 (158–250) | 0.13 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL FEU) | 790 (513–1398) | 1540 (760–2500) | < 0.001 |

| D-dimer ≥ 1500 ng/mL FEU on admission | 141 (23.0) | 89 (51.7) | < 0.001 |

| Max amplitude (mm) | 71.7 (69.0–77.1) | 63.9 (50.5–70.9) | 0.03 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Active cancer | 27 (4.4) | 14 (7.5) | 0.13 |

| Previous VTE | 15 (2.4) | 5 (2.7) | 0.79 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 0.67 |

| ASCVD | 53 (8.6) | 19 (10.2) | 0.56 |

| Known thrombophilia | 5 (0.8) | 4 (2.1) | 0.22 |

| Trauma/surgery | 6 (1.0) | 7 (3.7) | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 245 (39.8) | 89 (47.6) | 0.06 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20 (3.3) | 19 (10.2) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 199 (32.3) | 64 (34.2) | 0.66 |

| COPD | 25 (4.1) | 8 (4.3) | 0.84 |

| Asthma | 77 (12.5) | 25 (13.4) | 0.80 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 8 (1.3) | 2 (1.1) | 0.99 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 30 (4.9) | 21 (11.2) | 0.003 |

| Other chronic lung disease | 13 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0.99 |

| In-hospital problems | |||

| Acute kidney injury | 217 (35.2) | 112 (59.9) | < 0.001 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 27 (4.4) | 18 (9.6) | 0.01 |

| P:F ratio | 108 (81–136) | 100 (80–148) | 0.74 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 87 (14.1) | 75 (40.1) | < 0.001 |

| Requiring pressors | 90 (14.8) | 71 (38.0) | < 0.001 |

| Room air | 51 (8.3) | 16 (8.6) | 0.88 |

| Supplemental oxygen | 379 (61.5) | 74 (39.6) | < 0.001 |

| NIV or high-flow nasal cannula | 82 (13.3) | 18 (9.6) | 0.21 |

| Prophylactic initiation regimen | |||

| Enoxaparin 40 mg daily | 359 (58.3) | 87 (46.5) | 0.006 |

| Enoxaparin 30 mg BID | 162 (26.3) | 17 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg BID | 54 (8.8) | 14 (7.5) | 0.65 |

| Enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg BID | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.99 |

| UFH 5000 units TID | 20 (3.3) | 41 (21.9) | < 0.001 |

| UFH 7500 units TID | 18 (2.9) | 8 (4.3) | 0.35 |

| Enoxaparin 30 mg daily | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.23 |

| UFH 5000 units BID | 0 (0) | 15 (8.0) | < 0.001 |

| Dalteparin 5000 units daily | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 0.05 |

| UFH 10,000 units TID | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.23 |

| Anti-platelets | |||

| Aspirin | 90 (14.8) | 33 (17.7) | 0.35 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 13 (2.1) | 5 (2.7) | 0.58 |

| DAPT | 11 (1.8) | 4 (2.1) | 0.76 |

| Admission | |||

| Admitted to ward | 487 (79.0) | 116 (62.0) | < 0.001 |

| Admitted to ICU | 129 (21.0) | 71 (38.0) | < 0.001 |

| Admitted or transferred to ICU | 231 (37.5) | 107 (57.2) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay | 5 (3–10) | 8 (4–20) | < 0.001 |

| Admitted before protocol | 128 (20.8) | 114 (61.0) | < 0.001 |

| Admitted after protocol | 488 (79.2) | 73 (39.0) | < 0.001 |

All continuous data presented as median (IQR) and all nominal data presented as n (%)

BMI body mass index; CrCl creatinine clearance; FEU fibrinogen equivalent unit; VTE venous thromboembolism; ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; P:F PaO2 to FiO2 ratio; NIV non-invasive ventilation; BID twice daily; TID three times daily; DAPT dual antiplatelet therapy

The overall incidence of thrombotic events in this cohort was 6.6% (DVT 3.7%, PE 1.8%, arterial 1.1%); patients admitted to the ICU experienced a thrombosis rate of 12.4% and floor patients experienced a thrombosis rate of 3.7%. The per-protocol group experienced significantly fewer thrombotic events than the off-protocol group (4.4% vs 10.7%, p = 0.002). Incidence of DVT and PE was significantly lower in the per-protocol group as well, but no difference in arterial thrombosis was evident (Table 2). Major bleeding was significantly lower in the per-protocol group (3.1% vs 9.6%, p < 0.001) with bleeding at a critical site or a fall in hemoglobin requiring ≥ 2 units pRBCs driving this outcome (Table 2). Thirty-seven patients experienced major bleeding in this cohort, and 59.5% of those patients were receiving therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of bleed (Supplementary Table 2). Mortality was also significantly lower in the per-protocol group (6.3% vs 11.8%, p = 0.02). Patients in the off-protocol group were more likely to require an interruption in thromboprophylaxis due to suspected or confirmed bleeding. Off-protocol patients more often required an escalation to either a higher intensity prophylactic dose or therapeutic anticoagulation as well. There was no difference in the time from prophylaxis initiation to clot formation (Table 2). Details regarding prophylactic regimen use and regimen adjustments are found in Supplementary Tables 2–5.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Variable | Per-protocol (n = 616) | Off-protocol (n = 187) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombosis | 27 (4.4) | 20 (10.7) | 0.002 |

| Deep vein thrombosisa | 18 (2.9) | 12 (6.4) | 0.04 |

| Pulmonary embolisma | 6 (1.0) | 8 (4.3) | 0.006 |

| Ischemic strokea | 2 (0.3) | 2 (1.1) | 0.23 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| Peripheral arterial clot | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0.55 |

| Major bleeding | 19 (3.1) | 18 (9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Fatal bleeding | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| Major organ site | 14 (2.3) | 13 (7.0) | 0.004 |

| Hgb fall ≥ 2 g/dL | 14 (2.3) | 15 (8.0) | 0.001 |

| Requiring ≥ 2 units pRBCs | 13/14 (92.9) | 13/15 (86.7) | 0.99 |

| Mortality | 39 (6.3) | 22 (11.8) | 0.02 |

| Interruption in prophylaxis | 14 (2.3) | 12 (6.4) | 0.009 |

| Any escalation of prophylaxis | 105 (17.1) | 75 (40.1) | < 0.001 |

| Escalation according to protocol | 51 (8.3) | 16 (8.6) | 0.88 |

| Any change of prophylaxis | 124 (20.1) | 79 (42.3) | < 0.001 |

| Time from prophylaxis to thrombosis (days) | 8 (5–17) | 11 (7–16.5) | 0.32 |

All continuous data presented as median (IQR) and all nominal data presented as n (%)

aOne patient had both DVT and PE, and two patients had both DVT and stroke

Hgb hemoglobin; pRBC packed red blood cells

Multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated mechanical ventilation and male sex to be significant predictors of thrombosis, while a D-dimer ≥ 1500 ng/Ml FEU increased risk but did not reach significance (Table 3a). Post-hoc regression analysis of predictors for mortality found mechanical ventilation, major bleeding, D-dimer ≥ 1500 ng/Ml FEU, and RRT to significantly increase risk (Table 3b). Results of pre-specified subgroup analyses can be found in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of (a) thrombosis and (b) mortality

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Thrombosis | ||

| Required mechanical ventilation | 11.62 (5.72–23.63) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 2.45 (1.18–5.07) | 0.02 |

| D-dimer ≥ 1500 ng/mL FEU on admission | 1.73 (0.91–3.32) | 0.09 |

| Admitted prior to protocol implementation | 1.66 (0.86–3.21) | 0.13 |

| (b) Mortality | ||

| Required mechanical ventilation | 4.64 (2.37–9.10) | < 0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 5.25 (2.23–12.31) | < 0.001 |

| D-dimer ≥ 1500 ng/mL FEU on admission | 2.50 (1.36–4.56) | 0.003 |

| Required renal replacement therapy | 2.42 (1.02–5.74) | 0.04 |

Discussion

Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, thromboprophylaxis with a protocolized severity of illness, weight, and biomarker-based anticoagulation strategy was associated with an overall decreased incidence of thrombosis. Decreases in DVT and PE drove this outcome without an excess increase in major bleeding. Our protocol appeared to be protective against major bleeding, and mortality was significantly lower in the per-protocol group.

We assessed the effectiveness of a pragmatic, patient specific, targeted-intensity thromboprophylaxis strategy in patients with COVID-19 at risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. The overall incidence of thrombotic events in our cohort was lower than reported in previous studies [1–8, 10]. This may be due to the early implementation of the thromboprophylaxis protocol, initiation of prophylaxis within 48 h of admission, symptom-driven screening for thrombosis, or improved supportive strategies in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 over time. The relative risk reduction of thrombosis with receipt of a per-protocol regimen was 58.9%, which proved to be significant, with a number needed to treat of 16. Inclusion of severity of illness, weight, and relevant biomarkers in the protocol allowed for identification of higher risk patients that likely required increased doses of either enoxaparin or UFH to prevent clot formation. Current data is lacking in critically ill patients specifically, but no difference in mortality, advancement to ECMO, and thrombosis was observed in one recent randomized controlled trial comparing intermediate and standard prophylactic dosing strategies [20]. The median duration of hospitalization to randomization was 4 days in the aforementioned trial, which could have contributed to futility [20]. We observed non-statistically significant decreases in thrombosis in both per-protocol subgroups admitted to ICUs (9.3% vs 18.1%, p = 0.08) and wards (3.1% vs 6.0%, p = 0.16). A targeted protocol may therefore be beneficial to both critically ill and non-critically ill patients in future studies with early initiation of prophylaxis, but requires appropriately powered cohorts to confirm these initial findings.

Fewer patients experienced major bleeding in the per-protocol group. Initiation on a per-protocol regimen decreased need for escalation to therapeutic anticoagulation, which likely decreased overall risk as a majority of patients who bled were receiving full anticoagulation at the time. This may also indicate that intensified prophylactic dosing was more protective against thrombotic events. A growing body of evidence supports the use of empiric therapeutic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 [9, 21, 22]. However, questions regarding the balance between efficacy and safety of full therapeutic anticoagulation compared to a targeted strategy remain unanswered.

Mortality differed significantly between groups. Two recently published studies found significant reductions in mortality in patients receiving intermediate-intensity thromboprophylaxis regimens, which were consistent with our findings [14, 19]. Predictors of mortality have included male sex, age > 60, and increasing D-dimer [14]. This prompted our study group to perform a post-hoc regression analysis to identify other contributing factors. We found that mechanical ventilation, major bleeding, and RRT increased the risk of death significantly, indicating that the patients with highest severity of illness expectedly had the highest risk. While we did not see any significant difference in fatality directly attributable to major bleeding between our study groups, there was an associated risk of death with any major bleeding. In addition, an elevated D-dimer on admission was associated with an increased risk of mortality while thrombosis was not. Per-protocol thromboprophylaxis was not independently associated with a decrease in mortality, signaling that robust studies are needed to evaluate the effects of a targeted thromboprophylaxis regimen on mortality, especially in the critically ill.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated that mechanical ventilation and male sex significantly increased the risk of thrombosis. Similarly to the outcome of mortality, receipt of per-protocol thromboprophylaxis was not independently associated with a decrease in thrombosis which may limit the broad applicability of this study. Patients with highest severity of illness likely experienced highest risk of thrombosis secondary to the systemic inflammatory response known to affect patients with COVID-19 [33, 34]. It was therefore unsurprising to see that mechanical ventilation increased the odds of thrombosis by more than 11-fold. The risk conferred by male sex was consistent with current literature, but warrants further investigation [14, 16]. Elevated D-dimer on admission demonstrated a non-significant associated risk for thrombosis. This calls into question whether a higher threshold than 1500 ng/Ml FEU should be incorporated into a protocol to prevent thrombosis. Elevated D-dimer proved to be important in the prediction of both thrombosis and mortality, but further studies are needed to determine at what D-dimer value the risk for each of these outcomes is the highest.

This study had several limitations. Patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation within 24 h were excluded, which prevented inclusion of patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation empirically or as a form of off-protocol prophylaxis. This may have affected outcomes related to bleeding or mortality. Additionally, off-protocol patients were not always treated with a prophylactic regimen that might be considered the standard of care (e.g., UFH 10,000 units three times daily or enoxaparin 30 mg once daily). This population may not as accurately represent patients at highest risk of complications from COVID-19, including very young, elderly, and morbidly obese patients. We also did not collect information on concomitant medication use which may have affected thrombosis rate or mortality, such as known pro-coagulants or dexamethasone.

Conclusion

A patient-specific, targeted-intensity pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis protocol incorporating severity of illness, total body weight, and biomarkers was associated with a decrease in thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 on univariate analysis. This seemed consistent for patients admitted to the ICU or ward, but further studies in each of these populations are needed. Elevated D-dimer signaled an increased risk of thrombosis, but additional evaluation of a specific threshold for initiating prophylaxis at a higher intensity is warranted. A targeted protocol may prevent excess bleeding associated with therapeutic anticoagulation, but ongoing investigations can provide more definitive outcomes surrounding this strategy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

JEF had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: JEF, TCT, SWM, THK. Acquisition, interpretation, and analysis of data: all authors. Drafting of manuscript: JEF. Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: JEF, SWM, THK.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences (NCATS) Colorado CTSA [Grant Number UL1 TR002535]. Its contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. The funding source was not involved in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Exempt status obtained from Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMP, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L, Feng X, Zhang D, Jiang C, Mei H, Wang J, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Circulation. 2020;142(2):114–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beun R, Kusadasi N, Sikma M, Westerink J, Huisman A. Thromboembolic events and apparent heparin resistance in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42(Suppl 1):19–20. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maatman TK, Jalali F, Feizpour C, Douglas A, McGuire SP, Kinnaman G, et al. Routine venous thromboembolism prophylaxis may be inadequate in the hypercoagulable state of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(9):e783–e790. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hippensteel JA, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(3):e134–e137. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demelo-Rodríguez P, Cervilla-Muñoz E, Ordieres-Ortega L, Parra-Virto A, Toledano-Macías M, Toledo-Samaniego N, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer levels. Thromb Res. 2020;192:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criel M, Falter M, Jaeken J, Van Kerrebroeck M, Lefere I, Meylaerts L, et al. Venous thromboembolism in SARS-CoV-2 patients: only a problem in ventilated ICU patients, or is there more to it? Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):1. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01201-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, Chang HL, Moreno PR, Pujadas E, et al. Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenner WJ, Kanji R, Mirsadraee S, Gue YX, Price S, Prasad S, et al. Thrombotic complications in 2928 patients with COVID-19 treated in intensive care: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombol. 2021;51:595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11239-021-02394-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450–2457. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook D, Meade M, Guyatt G, Walter S, Heels-Ansdell D, Warkentin TE, et al. Dalteparin versus unfractionated heparin in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1305–1314. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han H, Yang L, Liu R, Liu F, Wu KL, Li J, et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meizlish ML, Goshua G, Liu Y, Fine R, Amin K, Chang E, et al. Intermediate-dose anticoagulation, aspirin, and in-hospital mortality in COVID-19: a propensity score-matched analysis. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:471–479. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Samkari H, Gupta S, Leaf RK, Wang W, Rosovsky RP, Brenner SK, et al. Thrombosis, bleeding, and the observational effect of early therapeutic anticoagulation on survival in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:622–632. doi: 10.7326/M20-6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiezia L, Boscolo A, Poletto F, Cerruti L, Tiberio I, Campello E, et al. COVID-19-related severe hypercoagulability in patients admitted to intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(6):998–1000. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panigada M, Bottino N, Tagliabue P, Grasselli G, Novembrino C, Chantarangkul V, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paolisso P, Bergamaschi L, D'Angelo EC, Donati F, Giannella M, Tedeschi S, et al. Preliminary experience with low molecular weight heparin strategy in COVID-19 patients. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1124. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadeghipour P, Talasaz AH, Rashidi F, Sharif-Kashani B, Beigmohammadi MT, Farrokhpour M, et al. Effect of intermediate-dose vs standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation on thrombotic events, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment, or mortality among patients with COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit: the INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1620–1630. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, Russak AJ, Glicksberg BS, Levin MA, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(1):122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NIH. Full-dose blood thinners decreased need for life support and improved outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: National Institutes of Health; 2021 https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/full-dose-blood-thinners-decreased-need-life-support-improved-outcome-hospitalized-covid-19-patients

- 23.Zhai Z, Li C, Chen Y, Gerotziafas G, Zhang Z, Wan J, et al. Prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism associated with coronavirus disease 2019 infection: a consensus statement before guidelines. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(6):937–948. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, Carrier M, Collen JF, Doerschug K, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of vte in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, Blumenstein M, Clark NP, Cuker A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombol. 2020;50(1):72–81. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, Connors JM, Hunt BJ, Iba T, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859–1865. doi: 10.1111/jth.14929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marietta M, Ageno W, Artoni A, De Candia E, Gresele P, Marchetti M, et al. COVID-19 and haemostasis: a position paper from Italian Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (SISET) Blood Transfus. 2020;18(3):167–169. doi: 10.2450/2020.0083-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, Angchaisuksiri P, Blair C, Dane K, et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5(3):872–888. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Group NIoNDaSr-PSS Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, Kastritis E, Sergentanis TN, Politou M, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(7):834–847. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connors JM, Levy JH. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1559–1561. doi: 10.1111/jth.14849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.