Abstract

Retinal surgery can be performed only by surgeons possessing advanced surgical skills because of the small, confined intraocular space, and the restricted free motion of instruments in contact with the sclera. Snake-like robots could be essential for use in retinal surgery to overcome this problem. Such robots can approach from suitable directions and operate delicate tissues when performing retinal vein cannulation, epiretinal membrane peeling and so on. In this study, we propose an improved integrated robotic intraocular snake (I2RIS), which is a new version of our previous IRIS. This update focuses on the dexterous distal unit design and the drive unit design. The proposed dexterous distal unit consists of small elements with reduced contact stress. The proposed drive unit includes a new wire drive mechanism where the drive pulley is mounted at a right angle relative to the actuation direction (also, relative to the conventional direction). A geometric analysis and mechanical design show that the proposed drive mechanism is simpler and easier to assemble and yields higher accuracy than the conventional drive mechanism. Furthermore, considering clinical use, the instrument of the I2RIS is detachable from the motor unit for cleaning, sterilization, and attachment of various surgical tools. Weighing merely 31.3 g, the proposed mechanism is only one third of the weight of the conventional IRIS. The basic functions and effectiveness of the proposed mechanism are verified by experiments on 5:1 scaled-up models of the dexterous distal unit and actual-size models of the instrument and motor units.

Keywords: medical robot, retinal surgery, microsurgery, mechanism design

I. Introduction

Retinal surgery is the one of the most difficult procedures that can be performed only by surgeons possessing advanced surgical skills. These surgeons must perform operations in the small, confined intraocular space using instruments with restricted free motion in the sclera. Many robotic systems that assist in retinal surgery and enhance surgical skill have been developed to overcome this problem [1]. These robots are teleoperated robotic systems controlled by a trackball [2], joystick [3], or a master arm [4]; cooperatively controlled robotic systems [5, 6]; handheld robots or devices [7-12], and an untethered microrobot [13]. The Steady-Hand Eye Robot (SHER) [5] enables smooth tool manipulation using a cooperative control scheme between the surgeon and a robot arm. The SHER system enhances tool manipulation accuracy in various vitreoretinal surgery tasks.

Snake-like robots could be essential for use in future retinal surgery. Such robots can approach a target from suitable directions and operate delicate tissues. However, the conventional snake-like robots [14-19] are difficult to implement on a sub-millimeter scale level. In our earlier work, we presented the design of a dexterous handheld submillimeter intraocular robot called the Integrated Robotic Intraocular Snake (IRIS) [20]. The original dexterous distal unit of the IRIS adopts the principle of the variable neutral-line mechanism [21]. Subsequently, a more compact actuation unit with better resolution for the IRIS, preliminary operational evaluation of the IRIS, and its integration with the SHER system were presented [22]. However, considering clinical use, the previously developed IRISs [20, 22] are still large, heavy and complex mechanism. A more compact and simpler IRIS needs to be integrated in robotic systems for retinal surgery. Furthermore, the instrument should be detachable from the motor unit for cleaning, sterilization, and attachment of various types of surgical tools.

On the basis of our previous works [20, 22], this study is focused on the dexterous distal unit and drive unit designs. First, small elements with reduced contact stress are proposed. Next, a new drive unit is designed; it includes a new wire drive mechanism wherein the drive pulley is mounted at a right angle relative to the actuation direction, and the instrument unit is detachable. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed mechanism is demonstrated by experiments on 5:1 scaled-up models of the dexterous distal unit and actual-size models of instrument and motor units.

II. I2RIS design

Medical robots for retinal microsurgery require many strict system design specifications. Figure 1 shows the required specification of the dexterous distal unit of the IRIS based on our previous work [20]. The IRIS system needs to be small and compact. Therefore, both the dexterous distal unit design and the drive unit design are vital. This section presents the designs of the dexterous distal unit and the drive unit of the I2RIS.

Fig. 1.

Required specifications of dexterous distal unit [20].

A. Dexterous distal unit design

Figure 2 shows the conceptual design of the dexterous distal unit of the IRIS. The dexterous distal unit is composed of 12 disk-like elements, providing two degree of freedom (DOF) bending joints (pitch and yaw axis) actuated by four wires. Each element has cylindrical top and bottom surfaces and five holes as shown in Fig. 2 (b). The elements make contact with each other by these cylindrical surfaces. The cylindrical surfaces contact alternately in pitch and yaw direction. Each element bends about 7.5° or 9° for a 45° total bending at the six or five cylindrical surfaces gaps. According to the Herts theory, the elements’ contact length must be increased to reduce the contact stress [20]. As shown in Fig. 3, the contact length of the cylindrical surfaces can be increased by changing the positions of the wire holes. Moreover, a cylindrical contact region of 7.5° or 9° is enough for a yaw and pitch motion range of ±45°. This could also reduce the elements’ thickness from 0.25 mm to 0.15 mm, as shown in Fig. 3(c). The proposed dexterous distal units, which comprise the abovementioned elements, are shown in Fig. 4. The dexterous distal unit using the thirteen compact elements measures only 2 mm, as shown in Fig. 4(c).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual design of dexterous distal unit of IRIS: the unit is composed of 12 disk-like elements providing 2-DOF bending joints actuated by 4 wires. (a) overview; (b) three-view drawing of element (dimensions in mm) [20].

Fig. 3.

Element shape and wire hole positions: (a) conventional element; (b) conventional proposed element, which increases the contact surface (thereby reducing contact stress) by changing the hole positions; (c) compact proposed element, which is created by decreasing the dead space.

Fig. 4.

IRIS and I2RIS: (a) conventional element, (b) conventional proposed element, (c) compact proposed element.

B. Conceptual design of drive mechanism

In a wire drive mechanism, the wires are generally actuated by the rotational motion of a pulley or the linear motion of a lead screw. As shown in Fig. 5, the push-pull wire displacements and drive direction of a conventional drive mechanism are equal to drive wire’s. However, for a device with ϕ0.9 mm diameter and 45° bending motion range, the push-pull wire displacement is only about 0.2 mm. Therefore, maintaining the accuracy of bending angle control and assembling the parts of the drive mechanism are challenging. If the drive wire displacement is larger than the push-pull wire displacement, it will be easy to keep the accuracy of the bending angle control and assemble the parts of the drive mechanism.

Fig. 5.

Conventional wire drive mechanism: (a) rotation pulley type, (b) lead screw type. The push-pull wire displacements are equal to drive wire displacements. In the case of IRIS, the push-pull wire displacement is 0.216 mm for a 45° total bending of the dexterous distal unit.

Figure 6 shows the concept of the proposed wire drive mechanism, including coordinate systems. In this mechanism, a drive pulley is mounted at a right angle relative to the actuation direction, unlike that in the conventional pulley drive mechanism shown in Fig. 5(a). The direction of the drive wire displacement is almost right angle of the direction of the push-pull wire displacement. The drive pulley does not need to be a cylindrical surface. The end point of the wire is not wrapped around the drive pulley; it moves only in the x-y plane by the pulley rotation. The wire length between the origin (the wire entrance point) and the wire end point is changed by the pulley rotation. The relationship between the drive pulley rotation angle θin and the push-pull wire lengths li(i = 1,2) can be obtained by the following equation:

| (1) |

where r is the drive pulley radius, θoffi is the offset angle of the wire end point on the pulley, lY is the y-direction distance of the pulley center, and lZ is the z-direction distance from the origin to the end point of the wire on the pulley. Figures 7 and 8 show the two push-pull wire displacements Δli = li – li0 (i = 1,2). where li0 is the initial wire length, and the difference of the two push-pull wire displacements (Δl1 – Δl2) in the case of r: 5 mm, lY: 4.5 mm, lZ: 16 mm, and θoff1 : 10 °, θoff2 : 170°. Table I shows the motion range and the displacement of the proposed wire drive mechanism. The drive wire displacement rθin is about four times larger than the push-pull wire displacement Δli. The push-pull wire displacement Δli is changed almost linearly. The maximum error of the linearity is 2.7% with respect to the fitting line at a drive pulley rotation angle of ±20°. The difference of the two push-pull wire displacements (Δl1, – Δl2) is under 20 μm at the drive pulley rotation angle of ±20°. These results mean that the proposed wire drive mechanism can enable two-motor actuation with 2-DOFs. The previously developed IRISs [20, 22] performed four-motor actuation. Furthermore, this mechanism is suitable for wire drive mechanisms with a small displacement motion range, such as the dexterous distal unit of the IRIS.

Fig. 6.

Concept of the proposed wire drive mechanism and coordinate systems: (a) 3D drawing, (b) x-y plane 2D drawing. The drive pulley is mounted at a right angle relative to the actuation direction, unlike that in a conventional pulley drive mechanism.

Fig. 7.

Push-pull wire displacements: wire displacements are changed almost linearly. The maximum error of the linearity is 2.7% with respect to the fitting line at the drive pulley rotation angle of ±20°.

Fig. 8.

Difference of push-pull wire displacements: the difference is under 20 μm at the drive pulley rotation angle of ±20°.

TABLE I.

Motion range and displacement of proposed wire drive mechanism

| Items | Motion ranges and Displacements |

|

|---|---|---|

| Drive pulley rotation angle θinput | ±10° | ±20° |

| Drive wire displacement rθinput | ±0.87 mm | ±1.75 mm |

| Push-pull wire displacement Δli | ±0.22 mm | ±0.44 mm |

| Dexterous tip bending angle θoutput |

±45° | ±90° |

Figures 9 and 10 show 3D and 2D drawings, respectively, of the drive wire and the tension F . The relationship between the input torque T and the wire tension F is as follows:

| (2) |

where Fr = Fxysin θA, , .

Fig. 9.

3D drawing of drive wire and tension: (a) drive wire, (b) tension.

Fig. 10.

x-y plane 2D drawing of drive wire and tension: (a) drive wire, (b) tension.

When T = FR, R is expressed as follows:

| (3) |

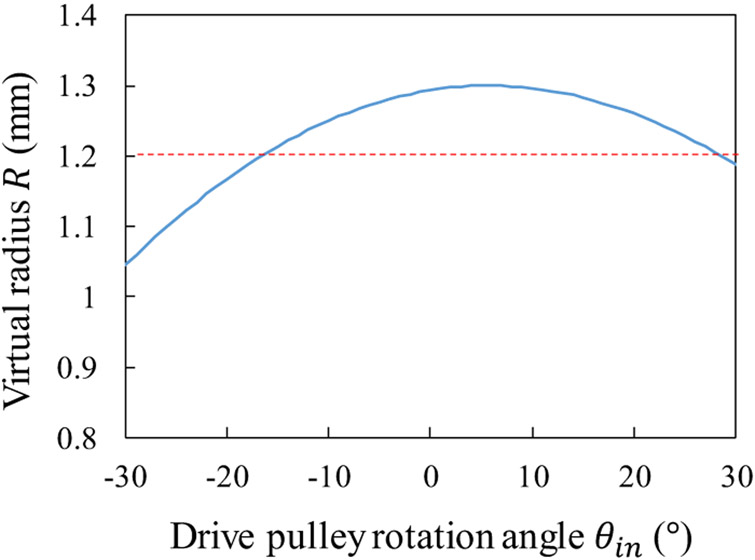

R can be defined as a “virtual radius.” Figure 11 shows the virtual radius under the same parameters of the l1 as those in Figs. 7. As shown in Fig. 11, the virtual radius is about 1.2 mm. This result means that the proposed mechanism is similar as the conventional pulley drive mechanism of about 1.2 mm pulley radius. The drive pulley’s real radius is 5 mm. Therefore, the proposed drive mechanism can enable easy assembly and higher accuracy than the conventional drive mechanism.

Fig. 11.

Virtual radius: the virtual radius is about 1.2 mm. The proposed mechanism is similar to an approximately 1.2 mm pulley radius and conventional wire drive mechanism.

C. Instrument and motor unit design

The instruments of medical robots are usually detachable from the robot body because of the required cleaning, sterilization, and attachment of various surgical tools. Therefore, the instrument of the proposed IRIS should be detachable. Figures 13 and 14 show the instrument and motor unit. It can be easily attached and detached from the motor unit using handle levers and guiding pins and holes. Figure 14 compares the proposed and conventional IRISs. The proposed mechanism is a quarter of the volume of the conventional IRIS.

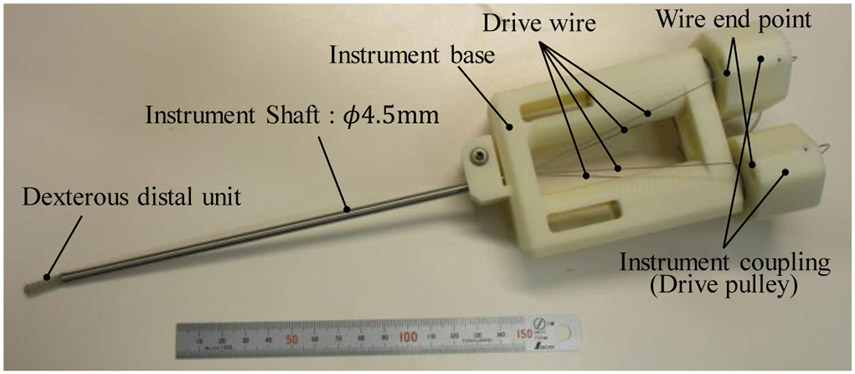

Fig. 13.

Instrument and motor units: the instrument unit is detachable from the motor unit.

Fig. 14.

(a) Conventional IRIS [22], (b) proposed IRIS (I2RIS): the I2RIS is a quarter of the volume of the conventional IRIS.

III. Experimental results and discussion

The effectiveness of the proposed mechanism is verified by experiments on 5:1 scaled-up models of the dexterous distal unit and actual-size models of the instrument and motor units.

A. 5:1 scaled-up models of the dexterous distal unit

Figure 15 shows an overview of the scaled-up models of the instrument unit, including the dexterous distal unit. This experiment aimed to confirm the basic functions of the proposed drive mechanism and the bending motions of the three types of dexterous distal unit elements. The instrument base shape was simplified. These elements were made of 3D-printed ABS. The drive wires were ϕ0.45 mm (7 × 19) wires made of SUS 304. Therefore, the hole sizes were changed from ϕ1.0 mm to ϕ0.6 mm to maintain the ratio of the wire diameter to the hole diameter. Figure 16 shows the bending motion range experiment results for the three types of dexterous distal unit elements shown in Fig. 3. The ±45° yaw and pitch bending motions were performed. Even in the case of the elements of changing the hole positions, yaw or pitch bending motions were performed by independently rotation of each drive pulley. The maximum motion range of types (a) and (b) were about ±90° and types (c) was about ±65°. If needed, the motion range of type (c) can be enhanced by increasing the number of elements. The basic functions of the proposed drive mechanism and the bending motions of the three types of dexterous distal unit elements were confirmed by the scaled-up model experiments. Furthermore, this mechanism can perform a further multistage, multi-DOF drive, such as a 2-stage, 4-DOF drive using 9-holed elements at the proximal stage, from the current 1-stage, 2-DOF drive. However, additional experimental data should be obtained to clarify, which elements are superior in accuracy, precision, and repeatability.

Fig. 15.

Overview of scaled-up models of the instrument unit.

Fig. 16.

Bending motion ranges of 5:1 scaled-up models: (a) conventional element, Fig. 2(a); (b) conventional proposed element, which increases the contact surface (thereby reducing contact stress) by changing the hole positions, Fig. 2(b); (c) compact proposed element, which is created by decreasing the dead space, Fig. 2(c).

B. Actual-size models of instrument and motor units

Figure 17 shows an overview of the actual-size models of the instrument and motor units. These elements were conventional parts made of brass. The elements can be manufactured by machining using drills and end mills. The drive wires were ϕ0.15 mm (1 × 19) wires made of SUS 304. A preliminary experiment confirmed that a nitinol wire has lower stiffness, larger friction, and larger hysteresis than a SUS wire. Therefore, the SUS wire was selected. The distal ends of the wires were fixed at the top element by knots, and the proximal ends of the wires were fixed at the drive pulley with glue. The other mechanical parts were made of 3D-printed ABS. The weights of the instrument and motor units were 6.0 and 25.3 g, respectively. The total weight of 31.3 g is one-third of the conventional IRIS (about 95 g). The instrument unit could easily be attached and detached from the motor unit using handle levers and guiding pins and holes, as shown in Fig. 17. The instrument couplings returned to their original positions automatically because of the restitution force by the wire tension. Therefore, the instrument couplings could be easily aligned with the motor couplings when attaching the instrument.

Fig. 17.

Overview of actual-size models of instrument and motor units: (a) attached state, (b) detached state.

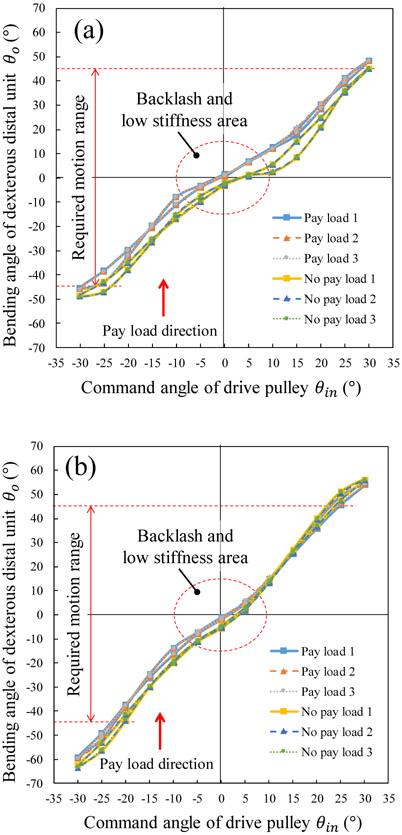

Figure 18 shows an overview of the experimental setup for motor drive operation. The motor coupling was driven by a servo system (Maxon Motor Inc.) consisting of a DC servo motor (DCX8M) with a reduction gear (GPX8, gear ratio 64:1) and an encoder (ENX 8MAG 256 pulses/revolution), and a controller (EPOS2 24/2). Figures 19 and 20 show the motor drive experiment results; relationship between the command angle of drive pulley θin and the bending angle of the dexterous distal unit in the case of payload (34 mN) and no payload, and three times measurement each. The bending angle was measured from pictures of a nitinol wire inserted into the center hole of the distal unit, as shown in Fig. 19. The required motion range of ±45° was obtained by the command angle of a drive pulley angle of ±30° or less even when the payload was 34 mN. The hysteresis between the command and bending angles was ±3.3° or less. There were a backlash and a low-stiffness area near the command angle 0° as shown in Figs. 20(a) and (b). This could be caused by the planetary gear, couplings, clearance between the wires and wire holes, and so on. The command angle was larger than the theoretical value. This could be caused by the backlash, torsional stiffness, wire elongation, and so on. The specifications of the I2RIS from the experimental results are shown in Table II.

Fig. 18.

Overview of experimental setup for motor drive operation.

Fig. 19.

Motor drive experiment of actual-size model: command angle of drive pulley θin and bending angle of dexterous distal unit.

Fig. 20.

Command angle of drive pulley θin and bending angle of dexterous distal unit θo : (a) yaw axis, (b) pitch axis. The payload is 34 mN.

TABLE II.

Specifications of developed I2RIS

| Items | Specifications | |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of distal tip | Diameter | 0.9 mm |

| Bending length | 3 mm (in the case of using small elements: 2 mm) | |

| Range of motion | Pitch | > ±45° |

| Yaw | > ±45° | |

| Payload | > 30 mN | |

| Instrument unit weight | 6.0 g | |

| Motor unit weight | 25.3 g | |

| Total volume without shaft and distal tip | 20 × 20 × 75 mm | |

IV. Conclusion

On the basis of our previous works on IRIS [20, 22], we have developed I2RIS, an improved, simpler, and more compact IRIS. The proposed dexterous distal unit consists of smaller elements with reduced contact stress. The proposed drive unit includes a new wire drive mechanism wherein the drive pulley is mounted at a right angle orientation. Furthermore, the instrument of the I2RIS is detachable from the motor unit for cleaning, sterilization, and attachment of various surgical tools. The effectiveness of the I2RIS was demonstrated by 5:1 scaled-up models of the dexterous distal unit and actual-size models of the instrument and motor units.

Future works toward clinical use grade are planned as follows: (1) further analysis and experiments on the dexterous distal unit using the proposed elements; (2) implementation of an end effector, such as a needle, grasper, optical fiber, and energy device, on the dexterous distal unit; (3) integration of this mechanism with the SHER system or other RCM mechanisms; (4) development of a handheld IRIS; and (5) development of a 2-stage, 4-DOF drive mechanism using 8-holed elements at the proximal stage.

Fig. 12.

Instrument unit: (a) overview, (b) cross section.

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to thank JHU LCSR Postdoctoral Fellow, Gang Li, Ph.D. for his help with the motor drive controller set-up.

Research supported in part by the off-campus researcher dispatch program of Kokushikan University, by U.S. National Institutes of Health under grant number 1R01EB023943-01, and by Johns Hopkins University internal funds.

Contributor Information

Makoto Jinno, School of Science and Engineering, Mechanical Engineering Course, Kokushikan University, Tokyo, Japan; Whiting School of Engineering, Laboratory for Computational Sensing and Robotics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA.

Iulian Iordachita, Whiting School of Engineering, Laboratory for Computational Sensing and Robotics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA.

References

- [1].Vander Poorten E, Riviere CN, Abbott JJ, Bergeles C, Nasseri MA, Kang JU, Sznitman R, Faridpooya K, and Iordachita I, 36 - Robotic Retinal Surgery, Handbook of Robotic and Image-Guided Surgery, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 627–672. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jensen PS, Grace KW, Attariwala R, Colgate JE, Glucksberg MR, “Toward robot-assisted vascular in the retina,” Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Vol. 235, no. 11, pp.696–701. November. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wei W, Popplewell C, Chang S, Fine HF, Simaan N, “Enabling technology for microvascular stenting in ophthalmic surgery,” Journal of Medical Devices, vol. 4, no. 1, March. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tanaka S, et al. “Quantitative assessment of manual and robotic microcannulation for eye surgery using new eye model,” hit J Med Robotics Comput Assist Surg, April.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fleming I, Balicki M, Koo J, Iordachita I, Mitchell B, Handa J, Hager G, Taylor R, “Cooperative robot assistant for retinal microsurgery,” Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv, vol. 5242. 2008. pp.543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gijbels A, Wouters N, Stalmans P, Van Brussel H, Reynaerts D, Vander Poorten E, “Design and realisation of a novel robotic manipulator for retinal surgery,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, 2013, pp.3598–3603. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ikuta K, Kato T, Nagata S, “Micro active forceps with optical fiber scope for intra-ocular microsurgery. Micro Electro Mechanical Systems,” Proceedings of Ninth International Workshop on Micro Electromechanical Systems, 1996, pp.456–461. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Latt WT, Tan UX, Shee CY, Ang WT, “A compact handheld active physiological tremor compensation instrument,” Proc. lEEE/Amer. Soc. Mech. Eng. Int. Conf. Adv. Intell. Mechatronics, 2009. pp.711–716. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Becker BC, Yang S, MacLachlan RA, Riviere CN, “Towards vision-based control of a handheld micromanipulator for retinal cannulation in an eyeball phantom,” Proc. 4th IEEE RAS EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatron, 2012, pp.44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Payne CJ, Kwok K, Yang G, “An ungrounded hand-held surgical device incorporating active constraints with force-feedback,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS ‘13), 2013, PP.2559–2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chang D, Gu GM, Kim J, “Design of a novel tremor suppression device using a linear delta manipulator for micromanipulation,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS ‘13), 2013, pp.413–418. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saxena A, Patel RV, “An active handheld device for compensation of physiological tremor using an ionic polymer metallic composite actuator,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS ‘13), 2013, pp.4275–4280. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kummer MP, Member SS, Abbott JJ, Kratochvil BE, Borer R, Sengul A, Nelson BJ, “OctoMag: An Electromagnetic System for 5-DOF Wireless Micromanipulation”, IEEE Transactions on Robotics. Vol. 26, no. 6, pp.1006–1017, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ikuta K, Yamamoto K, Sasaki K, “Development of remote microsurgery robot and new surgical procedure for deep and narrow space,” IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2003, pp. 1103–1108. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ding J, Xu K, Goldman R, Allen P, Fowler D, Simaan N, “Design simulation and evaluation of kinematic alternatives for insertable robotic effectors platforms in single port access surgery”, IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2010. pp. 1053–1058. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kutzer MD, Segreti SM, Brown CY, Armand M, Taylor RH, Mears SC, “Design of a new cable-driven manipulator with a large open lumen: Preliminary applications in the minimally-invasive removal of osteolysis,” IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2011, pp. 2913–2920. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Haraguchi D, Tadano K, Kawashima K, “A prototype of pneumatically-driven forceps manipulator with force sensing capability using a simple flexible joint,” IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and System, 2011, pp. 931–936. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Roppenecker DB, Pfaff A, Coy JA, Lueth TC, “Multi arm snake-like robot kinematics,” IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2013, pp. 5040–5045. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Qi P, Qiu C, Liu H, Dai JS, Seneviratne L, Althoefer K, “A novel continuum-style robot with multilayer compliant modules,” IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and System, 2014, pp.3175–3180. [Google Scholar]

- [20].He X, Geirt VV, Taylor R, lordachita I, “IRIS: Integrated robotic intraocular snake,” IEEE International Conference on robotics and automation, 2015, pp.1764–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kim Y-J, Cheng S, Kim S, and Iagnemma K, “A stiffness-adjustable hyperredundant manipulator using a variable neutral-line mechanism for minimally invasive surgery,” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 382–395, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Song J, Gonenc C, Guo J, Iordachita I, “Intraocular Snake Integrated with the Steady-Hand Eye Robot for Assisted Retinal Microsurgery,” IEEE International Conference on robotics and automation, 2017, pp.6724–6729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]