Abstract

The gut of honey bees is characterized by a stable and relatively simple community of bacteria, consisting of seven to ten phylotypes. Two closely related honey bees, Apis mellifera (western honey bee) and Apis cerana (eastern honey bee), show a largely comparable occurrence of those phylotypes, but a distinct set of bacterial species and strains within each bee species. Here, we describe the isolation and characterization of Ac13T, a new species within the rare proteobacterial genus Frischella from A. cerana japonica Fabricius. Description of Ac13T as a new species is supported by low identity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence (97.2 %), of the average nucleotide identity based on orthologous genes (77.5 %) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization relatedness (24.7 %) to the next but far related type strain Frischella perrara PEB0191T, isolated from A. mellifera. Cells of Ac13T are mesophilic and have a mean length of 2–4 µm and a width of 0.5 µm. Optimal growth was achieved in anoxic conditions, whereas growth was not observed in oxic conditions and strongly reduced in microaerophilic environment. Strain Ac13T shares several features with other members of the Orbaceae, such as the major fatty acid profile, the respiratory quinone type and relatively low DNA G+C content, in accordance with its evolutionary relationship. Unlike F. perrara, strain Ac13T is susceptible to a broad range of antibiotics, which could be indicative for an antibiotic-free A. cerana bee keeping. In conclusion, we propose strain Ac13T as a novel species for which we propose the name Frischella japonica sp. nov. with the type strain Ac13T (=NCIMB 15259=JCM 34075).

Keywords: Apis cerana, Frischella, gut microbiota, honey bee

Social corbiculate bees, including honey bees and bumble bees, have previously been shown to harbour specialized gut microbiota, which can be detected in bee guts or the hive environment but not elsewhere [1, 2]. This bacterial community is transmitted between bees by social interactions [3] and consists of seven to ten phylotypes with five taxa consistently found in most host species and thus referred to as core microbiota. Core genera are Gilliamella and Snodgrassella of the Gram-stain-negative ‘Proteobacteria’, two Gram-stain-positive Lactobacillus species of the ‘Firmicutes’ phylum (Firm-4 and Firm-5) and, less abundant, Bifidobacterium of the ‘Actinobacteria’. Less numerous and prevalent rare phylotypes (i.e. only in some bee species and therein not in every individual) within honey bees are Commensalibacter, Bartonella and Frischella of the ‘Proteobacteria’ and Apibacter, belonging to the ‘Bacteroidetes’ [4].

The gut microbiome has major effects on host health and nutrition, including the degradation of (toxic) carbohydrates, immune system stimulation and protection against pathogens [5]. Especially interesting with respect to host interaction is the rare species Frischella perrara, presence of which in the distal pyloric part of the midgut in the western honey bee Apis mellifera co-occurs with a local melanization response of the host tissue [6], caused by strong activation of the immune system with potential implications for A. mellifera health [7]. Yet, research has focused on the globally important and widely distributed honey bee species A. mellifera, with many bacterial isolates available, while analysis of the microbiome of the eastern honey bee Apis cerana is still scarce. A recent study comparing the microbiome of A. mellifera and A. cerana in Japan using shotgun metagenomics demonstrated that, despite an overall consistent composition on phylotype level, both honey bee species show a distinct bacterial composition with different species and variable rare taxa [8]. This suggests that unique gut microbes have co-evolved with A. cerana and may have a profound impact on the host physiology.

Here, we present the isolation, cultivation and physiological characterization of a new species of Frischella isolated from the gut of eastern honey bee A. cerana japonica Fabricius specimens from Japan, and propose the name Frischella japonica sp. nov.

Strain Ac13T was isolated from the gut homogenate of inhive bees of an A. cerana japonica colony in Isumi, Chiba, Japan (35° 13′ 00.9″ N, 140°23′12.9″ E) in September 2017. Bees were immobilized by chilling at 4 °C before their guts were dissected with sterile forceps. Three guts were pooled in a 2 ml reaction tube and homogenized in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl) by bead-beating with 1 mm glass-beads in a MicroSmash MS-100 homogenizer (TOMY) at 5500 r.p.m. for 30 s. The gut homogenate was stored at −80 °C supplemented with 15 % w/v glycerol. Thawed gut homogenate was plated on Columbia blood agar (CBA; Difco BD) with 5 % v/v defibrinated sheep blood (Nippon Bio-test Lab), incubated at 37 °C with 5 % v/v CO2 in air until bacterial colonies became visible after 4 days.

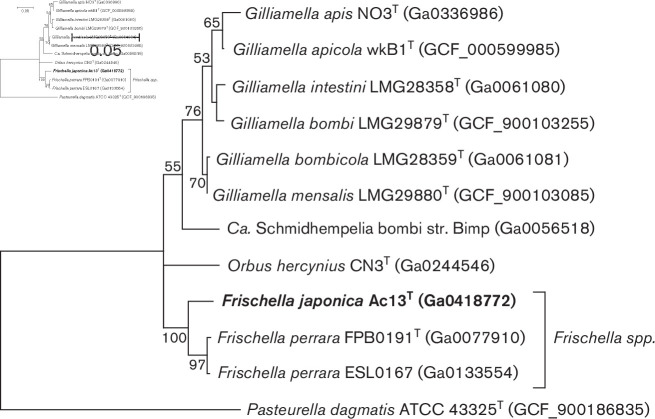

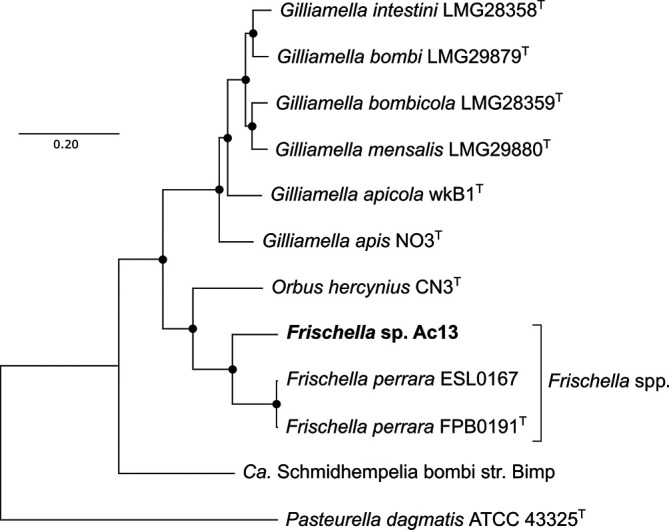

Comparative sequence analyses based on the 16S rRNA gene and single-copy core genes were performed between strain Ac13T and other described type species of the Orbaceae. DNA of strain Ac13T for whole genome sequencing was extracted using NucleoSpin Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel). The genomic sequence of strain Ac13T (accession number: JABURY01) was obtained by Illumina NovaSeq6000 2×150 bp pair-end platform with 670× coverage. The trimmed reads could be assembled into 39 contigs with a total length of 2 656 327 bp and an N50 value of 219 086. Of the total 2416 genes, 2342 were identified as protein-coding and 56 identified as RNAs. DNA G+C content of 34.5 mol% and total genome assembly length of 2.66 Mb resemble the characteristics of F. perrara PEB0191T. The genome-derived complete 16S rRNA gene sequence of Ac13T was phylogenetically compared to the almost-complete 16S rRNA genes of relevant type species within the Orbaceae including Gilliamella species, Orbus hercynius DES39, ‘Candidatus Schmidhempelia bombi’ O970 and Pasteurella dagmatis ATCC 43325 of the closest-related family to the Orbaceae for rooting the tree (1512 sites). The 16S rRNA gene sequences were aligned using mafft version 7.427 [9], the best substitution model was computed using jModelTest version 2 [10] and the selection confirmed with Modeltest-NG [11]. The suggested model was the TIM3 substitution model with four discrete Gamma categories and invariable sites based on AIC, AICc and BIC. The maximum-likelihood phylogeny with 1000 bootstrap replicates was calculated using the iq-tree software version 2.1.2 [12] and visualized using mega-X version 10.0.5 [13]. Whole-genome phylogeny was performed with same described type species on amino acid sequences of 890 single-copy orthologous genes, retrieved using Orthofinder version 2.3.3 [14], aligned using mafft and concatenated. The concatenated alignment of the core genes was automatically curated for blocks represented by >50 % sequence information using Gblocks with the providers’ parameters for protein sequences [15]. The best substitution model was computed using Modeltest-NG. The improved general amino acid replacement matrix (LG) [16] with four discrete Gamma categories and invariable sites was suggested based on AIC, AICc and BIC. The maximum-likelihood phylogeny of the concatenated single-copy gene alignments with 100 bootstrap replicates was calculated using iq-tree and visualized using mega-X. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and 890 single-copy orthologous genes identified the new isolate Ac13T as a member of the Orbaceae of the Orbales in the Gammaproteobacteria. Ac13T deeply branched into a distinct species within the genus Frischella, supported by 100 % of bootstrap replications for 16S rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 1) and whole-genome phylogeny (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic placement based on 16S rRNA sequence alignment (1512 sites) of Ac13T and other type strains of the Orbaceae, including the yet-described type species of the genus Gilliamella, F. perrara, Orbus hercynius and ‘Ca. Schmidhempelia bombi’ aligned using mafft. For rooting the tree, Pasteurella dagmatis ATCC 43325 of the closest related family to the Orbaceae was included. The maximum-likelihood tree was inferred using iq-tree using the TIM3 substitution model with four discrete Gamma categories and invariable sites (TIM3+I+G4) with 1000 bootstrap replicates; values >50 % are shown. Bar, 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position. Accession numbers (NCBI or IMG) of genomic data from which 16S rRNA sequences were retrieved are shown in parentheses.

Fig. 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny based on 890 single-copy orthologous genes, retrieved from amino acid sequences of the whole genomes of the Orbaceae, including the yet-described type species of the genus Gilliamella, F. perrara, Orbus hercynius and ‘Ca. Schmidhempelia bombi’ aligned using mafft. For rooting the tree, Pasteurella dagmatis ATCC 43325 of the closest related family to the Orbaceae was included. The tree was inferred using iq-tree with the LG substitution model with four discrete Gamma categories and invariable sites on the amino acid sequences (LG+I+G4+F) with 100 bootstrap replicates. Dots represent nodes supported by 100 % of bootstrap replications. Bar, 0.2 substitutions per site.

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) values were calculated based on the complete genome assemblies used for phylogenetic analysis, chopped into 1024 bp fragments using the blast-based Orthologous Average Nucleotide Identity (OrthoANIb) algorithm [17]. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values were calculated by the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator GGDC 2.1 [18]. OrthoANIb values of 77.46 and 77.56 % to the type strain F. perrara PEB0191T and isolate ESL0167 (Tables 1 and S1, available in the online version of this article) and dDDH values of 24.7 and 25.5 % (Tables 1 and S2), respectively, support the branching of Ac13T into a new species in the genus Frischella with values well below the accepted thresholds of 95 % for ANI and 70 % for dDDH [19, 20].

Table 1.

Differential biochemical characteristics of strain Ac13T compared to type strains of the Orbaceae

Strain: 1, Ac13T; 2, Frischella perrara PEB0191T; 3, Gilliamella apicola wkB1T; 4, Orbus hercynius CN3T. +, positive; −, not detected; w, weak production; AN, anaerobe; MA, microaerobe; A, aerobe; R, rod-shaped cells; C, coccoid cells. Major fatty acid components are marked in bold. 16S rRNA gene sequence identities are based on the mafft alignment. For dDDH, results using Formula 1 (length of all high-scoring segment pairs divided by total genome length) are shown. Results using other formulas are summarized in Table S2.

|

Characteristic |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aerobic growth |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

|

Microaerophile |

+ |

− |

+ |

− |

|

Optimum growth temperature (°C) |

37 |

37 |

37 |

20–30 |

|

Morphology |

R |

R |

R |

R, C |

|

DNA G+C content (mol%) |

34.5 |

34.1 |

33.6 |

38.8 |

|

Genome size (Mb) |

2.66 |

2.69 |

3.14 |

2.36 |

|

16S rRNA gene sequence identity (%) |

100 |

97.2 |

96.0 |

94.6 |

|

OrthoANIb (%) |

100 |

77.5 |

73.8 |

71.1 |

|

dDDH (Formula 1) (%) |

100 |

24.7 |

14.1 |

13.4 |

|

Nitrate reduction |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

|

Catalase |

− |

+ |

− |

+ |

|

Cytochrome c oxidation |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

|

Urea hydrolysis |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

|

β-Glucosidase (aesculin) |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

β-Galactosidase (PNPG) |

− |

− |

+ |

− |

|

Acid production from fermentation of: |

||||

|

d-Glucose |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

l-Arabinose |

− |

w |

+ |

− |

|

d-Galactose |

− |

− |

+ |

− |

|

Lactose |

+ |

− |

+ |

− |

|

d-Mannitol |

+ |

− |

+ |

+ |

|

Raffinose |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

|

d-Sorbitol |

− |

− |

+ |

− |

|

Fatty acids (%): |

||||

|

C14 : 0 |

7.5 |

5.2 |

7.5 |

6.9 |

|

C16 : 0 |

42.0 |

35.1 |

31.7 |

33.7 |

|

C18 : 0 |

2.2 |

3.3 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

|

C16 : 1 ω7c/C16 : 1 ω6c |

4.7 |

2.0 |

9.4 |

10.7 |

|

C18 : 1 ω9c |

− |

0.8 |

− |

− |

|

C18 : 1 ω7c/C18 : 1 ω6c |

33.2 |

44.4 |

41.3 |

38.5 |

|

Others |

10.6 |

9.4 |

8.8 |

9.4 |

To determine optimal growth conditions, we tested different culture methods for Ac13T. The cells were resuspended in PBS, and equal volumes of bacterial suspension were used to inoculate cultures in trypticase soy agar (TSA; Difco BD), Columbia blood agar (CBA; Difco BD), brain–heart infusion agar (BHIA) and Gifu anaerobic medium (GAM; Nissui). Strain Ac13T did not grow under oxic conditions and growth was reduced in 5 % v/v CO2 conditions. In anoxia, growth was observed after 2–3 days on TSA and CBA with 5 % v/v defibrinated sheep blood. Very weak growth was observed on BHIA with defibrinated sheep blood but not without it. Ac13T also grew well on GAM agar. No haemolytic activity was observed when incubated on media containing defibrinated sheep blood. The initial pH range for anaerobic growth in peptone–yeast extract–glucose (PYG) broth (Hardy Diagnostics) was determined from pH 4 to 10 in steps of 0.5 pH units. The pH was adjusted by HCl or NaOH. We observed growth at pH 7.0–8.5 and weak growth at pH 6.5 and 9.0, which would allow growth of the strain in the proximal pyloric part of the midgut, comparable to F. perrara in A. mellifera [21]. For optimal temperature, a range from 15–40 °C in steps of 5 °C was tested and strain Ac13T grew best at 30 and 35 °C, corroborating relatively high preferred in vitro growth temperatures of other bee gut symbionts [22]. For long-term preservation, strain Ac13T was harvested from CBA supplemented with 5 % v/v defibrinated sheep blood plates and stored in PBS with final 15 % w/v glycerol at −80 °C.

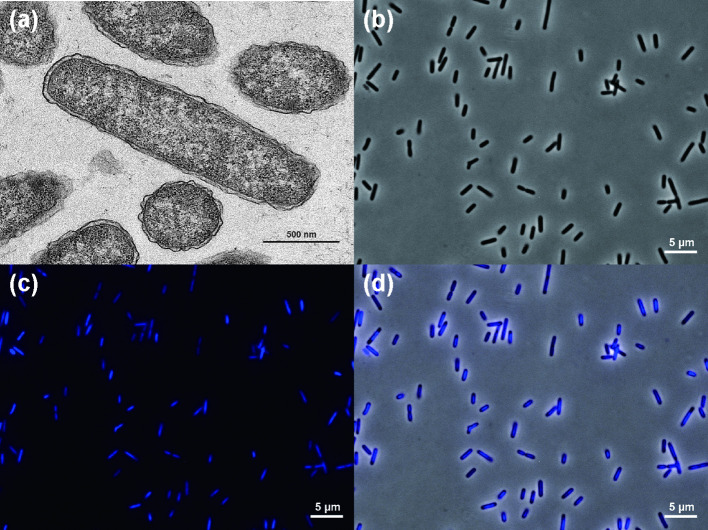

Using transmission electron microscopy (H-7600, Hitachi) and light microscopy (AxioImager, Zeiss), we characterized the morphology of strain Ac13T grown in PYG broth at 35 °C for 48 h under anoxic conditions (Fig. 3). Rod-shaped cells, 2–4 µm long and 0.5 µm wide, were the predominant morphological type of strain Ac13T.

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and light microscopy of cells of Frischella japonica Ac13T. Images of TEM (a), phase contrast (b), and fluorescence stained with Hoechst33342 (c) are shown. An overlay of the two light microscopy channels is shown in (d).

To describe the isolate further, a number of biochemical and metabolic analyses were performed. Results are summarized in Table 1, in comparison with published results for F. perrara PEB0191T, G. apicola wkB1T and Orbus hercynius CN3T [23]. Using API20A, API ZYM and API20 NE kit (bioMérieux), we found that strain Ac13T was negative for catalase (EC 1.11.1.6), nitrate reduction, indole production and cytochrome c oxidation and hydrolysis of urea, gelatin and PNPG (β-galactosidase substrate). Strain Ac13T was also negative for hydrolysis of aesculin (β-glucosidase substrate), while the three compared type strains were positive. Acid production from fermentation was observed with glucose, lactose and mannitol. Although strain Ac13T was negative for β-galactosidase (PNPG) activity, it could produce acid from fermentation of lactose, suggesting that the enzyme may not be secreted into the assay medium or may recognize lactose but not the artificial substrate PNPG.

Cellular fatty acid composition was determined by fatty acid methyl ester analysis (Sherlock MIS version 6.0, Microbial ID) from a culture of Ac13T grown in PYG broth at 35 °C for 48 h under anoxia, corresponding to the late-exponential phase. From the same exponential phase culture, predominant respiratory quinones were extracted according to Minnikin et al. [24], and identified using an Acquity UPLC H-Class system (Waters). Major fatty acids detected in Ac13T were palmitic acid (C16 : 0) and cis-vaccenic acid (C18 : 1 ω7c/C18 : 1 ω6c; Table 1). The major quinone was ubiquinone-8, a common feature of the Orbaceae [23, 25, 26].

Because a shared feature of F. perrara PEB0191T and G. apicola wkB1T is the resistance to oxytetracycline and other antibiotics, antibiotic susceptibility of isolate Ac13T was investigated. To this end, the strain was grown for 2 days on TSA supplemented with 5 % v/v defibrinated sheep blood, collected in PBS, and diluted until 0.5 McFarland. The cell suspension was spread on a fresh plate of the same medium. Using the disc diffusion assay, the following antibiotics were tested: ampicillin (20 µg), carbenicillin (30 µg), ceftazidime (25 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), gentamicin (25 µg), kanamycin (30 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg), oxytetracycline (30 µg), rifampicin (30 µg), spectinomycin (50 µg), streptomycin (10 µg) and tylosin (30 µg) and the inhibition zone measured after 2 days. Strain Ac13T showed no resistance to the tested antibiotics (Table S3). Antibiotic resistance in the honey bee microbiota was shown to reflect the history of antibiotic use in the habitat of the host bee [27] and susceptibility of Ac13T to all tested antibiotics thus might reflect a low usage of antibiotics to treat A. cerana colonies in Japan due to their rather low significance for economic production of honey [28].

The phenotypic, phylogenetic and biochemical analysis of strain Ac13T indicates that it represents a new species in the genus Frischella within the Orbaceae. We propose the name Frischella japonica based on its isolation from eastern honey bee A. cerana from Japan. Ac13T shares many characteristics to other members of the Orbaceae, including the respiratory quinone, a similar fatty acid profile and a low DNA G+C content (~34 mol%). However, ANI and dDDH values based on orthologs and the 16S rRNA gene sequence identity of 77.5, 24.7 and 97.2 %, respectively, to the closest relative F. perrara PEB0191T, clearly separates Ac13T from F. perrara PEB0191T through phylogenetic comparison. Phenotypically, Ac13T can be differentiated from F. perrara PEB0191T by utilizing lactose and d-mannitol for fermentation, missing catalase and β-glucosidase activities, and the broad susceptibility to a range of antibiotics.

Description of Frischella japonica sp. nov.

Frischella japonica, (ja.po′ni.ca. N.L. fem. adj. japonica pertaining to Japan).

Cells have a mean length of 2–4 µm and a width of 0.5 µm. Optimal growth is observed on TSA, CBA supplemented with 5 % v/v defibrinated sheep blood and GAM after 2–3 days in anoxia. On TSA with 5 % v/v sheep blood for 3 days, colonies of Ac13T are smooth, round, semi-translucent colonies with a shiny surface and a diameter of about 1 mm. No haemolysis is observed on media supplemented with sheep blood. Negative for catalase activity, nitrate reduction, indole production and cytochrome c oxidation and hydrolysis of urea, gelatin, β-galactosidase and β-glucosidase substrates.

Acid is produced from fermentation of d-glucose, lactose and d-mannitol. Susceptible to a broad range of antibiotics.

The type strain, Ac13T (=NCIMB 15259=JCM 34075), was isolated from the gut of an eastern honey bee, A. cerana japonica from Isumi, Chiba, Japan. The genomic DNA G+C content of the type strain is 34.5 mol% (by genome sequencing).

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This work was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency ERATO (JPMJER1502) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (19K22295). SS was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shohei Kanari for caring for the bee colonies and Kayo Ohkouchi for the preparation of the genomic DNA. Kirsten M. Ellegaard and Philipp Engel from the University of Lausanne are thanked for their help with genomic analysis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: R. M. Data curation: L. A. W. and R. M. Formal analysis: L. A. W. Funding acquisition: R. M. Investigation: L. A. W., S. S. and R. M. Methodology: L. A. W., S. S. and R. M. Project administration: R. M. Resources: R. M. Software: L. A. W. Supervision: R. M. Validation: L. A. W., S. S. and R. M. Visualization: L. A. W. and R. M. Writing – original draft: L. A. W. Writing – review and editing: L. A. W., S. S. and R. M.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANI, average nucleotide identity; BHIA, brain–heart infusion agar; CBA, Columbia blood agar; dDDH, digital DNA–DNA hybridization; GAM, Gifu anaerobic medium; OrthoANIb, blast-based Orthologous Average Nucleotide Identity; PNPG, p-nitrophenyl-beta-d-galactoside (β-galactosidase substrate); PYG, peptone–yeast extract–glucose; TSA, trypticase soy agar.

Three supplementary tables are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Koch H, Schmid-Hempel P. Bacterial communities in central European bumblebees: low diversity and high specificity. Microb Ecol. 2011;62:121–133. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinson VG, Danforth BN, Minckley RL, Rueppell O, Tingek S, et al. A simple and distinctive microbiota associated with honey bees and bumble bees. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong WK, Moran NA. Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:374–384. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwong WK, Medina LA, Koch H, Sing KW, Soh EJY, et al. Dynamic microbiome evolution in social bees. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1600513. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raymann K, Moran NA. The role of the gut microbiome in health and disease of adult honey bee workers. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018;26:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel P, Bartlett KD, Moran NA. The bacterium Frischella perrara causes scab formation in the gut of its honeybee host. mBio. 2015;6:e00193-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00193-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery O, Schmidt K, Engel P. Immune system stimulation by the gut symbiont Frischella perrara in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Mol Ecol. 2017;26:2576–2590. doi: 10.1111/mec.14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellegaard KM, Suenami S, Miyazaki R, Engel P. Vast differences in Strain-Level diversity in the gut microbiota of two closely related honey bee species. Curr Biol. 2020;30:2520–2531.:e2527. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura T, Yamada KD, Tomii K, Katoh K. Parallelization of MAFFT for large-scale multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2490–2492. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B. ModelTest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:291–294. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. megaX: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56:564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le SQ, Gascuel O. An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1307–1320. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee I, Ouk Kim Y, Park S-C, Chun J. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:1100–1103. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun J, Oren A, Ventosa A, Christensen H, Arahal DR, et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng H, Powell JE, Steele MI, Dietrich C, Moran NA. Honeybee gut microbiota promotes host weight gain via bacterial metabolism and hormonal signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:4775–4780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701819114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engel P, James RR, Koga R, Kwong WK, McFrederick QS, et al. Standard methods for research on Apis mellifera gut symbionts. J Apic Res. 2013;52:1–24. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.4.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel P, Kwong WK, Moran NA. Frischella perrara gen. nov., sp. nov., a gammaproteobacterium isolated from the gut of the honeybee, Apis mellifera . Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:3646–3651. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.049569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minnikin DE, O'Donnell AG, Goodfellow M, Alderson G, Athalye M, et al. An integrated procedure for the extraction of bacterial isoprenoid quinones and polar lipids. J Microbiol Methods. 1984;2:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0167-7012(84)90018-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JY, Lee J, Shin NR, Yun JH, Whon TW, et al. Orbus sasakiae sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from the gut of the butterfly Sasakia charonda, and emended description of the genus Orbus . Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:1766–1770. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.041871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwong WK, Moran NA. Cultivation and characterization of the gut symbionts of honey bees and bumble bees: description of Snodgrassella alvi gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Neisseriaceae of the Betaproteobacteria, and Gilliamella apicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of Orbaceae fam. nov., Orbales ord. nov., a sister taxon to the order 'Enterobacteriales' of the Gammaproteobacteria . Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:2008–2018. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.044875-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian B, Fadhil NH, Powell JE, Kwong WK, Moran NA. Long-term exposure to antibiotics has caused accumulation of resistance determinants in the gut microbiota of honeybees. mBio. 2012;3:e00377-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00377-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohsaka R, Park MS, Uchiyama Y. Beekeeping and honey production in Japan and South Korea: past and present. J Ethn Foods. 2017;4:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2017.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.