Abstract

Strains of the genus Bradyrhizobium associated with agronomically important crops such as soybean (Glycine max) are increasingly studied; however, information about symbionts of wild Glycine species is scarce. Australia is a genetic centre of wild Glycine species and we performed a polyphasic analysis of three Bradyrhizobium strains—CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T, and CNPSo 4019T—trapped from Western Australian soils with Glycine clandestina, Glycine tabacina and Glycine max, respectively. The phylogenetic tree of the 16S rRNA gene clustered all strains into the Bradyrhizobium japonicum superclade; strains CNPSo 4010T and CNPSo 4016T had Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T as the closest species, whereas strain CNPSo 4019T was closer to Bradyrhizobium liaoningense LMG 18230T. The multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) with five housekeeping genes—dnaK, glnII, gyrB, recA and rpoB—confirmed the same clusters as the 16S rRNA phylogeny, but indicated low similarity to described species, with nucleotide identities ranging from 93.6 to 97.6% of similarity. Considering the genomes of the three strains, the average nucleotide identity and digital DNA–DNA hybridization values were lower than 94.97 and 59.80 %, respectively, with the closest species. In the nodC phylogeny, strains CNPSo 4010T and CNPSo 4019T grouped with Bradyrhizobium zhanjiangense and Bradyrhizobium ganzhouense, respectively, while strain CNPSo 4016T was positioned separately from the all symbiotic Bradyrhizobium species. Other genomic (BOX-PCR), phenotypic and symbiotic properties were evaluated and corroborated with the description of three new lineages of Bradyrhizobium. We propose the names of Bradyrhizobium agreste sp. nov. for CNPSo 4010T (=WSM 4802T=LMG 31645T) isolated from Glycine clandestina, Bradyrhizobium glycinis sp. nov. for CNPSo 4016T (=WSM 4801T=LMG 31649T) isolated from Glycine tabacina and Bradyrhizobium diversitatis sp. nov. for CNPSo 4019T (=WSM 4799T=LMG 31650T) isolated from G. max.

Keywords: Bradyrhizobium, wild soybean, Glycine, nodulation, MLSA, ANI, dDDH

Introduction

Balanced levels of N in soil are required to obtain high productivities and healthy plants. Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is carried out by a restricted group of prokaryotes able to reduce the atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) to ammonium (NH3), the assimilable form by plants [1, 2]. The highest level of evolution of BNF occurs with the symbiotic interaction between diazotrophic bacteria collectively known as rhizobia and members of the family Fabaceae (=Leguminosae). The symbiosis involves a mutual exchange of molecular signals, culminating in the development of specialized structures on roots, and occasionally on stems, called nodules, in which the BNF process takes place [3, 4]. A variety of elite rhizobial strains have been introduced in agricultural systems for over a century as a sustainable way to improve soil fertility and crop yield, in addition to lowering costs, due to the replacement of chemical N-fertilizers [5, 6]. One remarkable example relies on the symbiosis of Bradyrhizobium with the soybean (Glycine max) crop in Brazil, saving billions of dollars every year [7, 8].

Several Bradyrhizobium species have been isolated from nodules of soybean, mostly grown in China, the main genetic centre of this legume species [9–11]. However, Bradyrhizobium is a geographically widespread genus that nodulates several legume tribes, from herbaceous to trees, mainly in tropical regions [12–15]. Recently, Helene et al. [16] reported a high diversity of Bradyrhizobium strains isolated from Western Australian soils using species of Glycine species as trapping hosts. It is worth mentioning that the genus Glycine is split into two subgenera: Soja, with Glycine max and Glycine soja species, and Glycine, which includes 25 species of wild soybean, most indigenous to Australia [17–20]; for this reason, although not often mentioned, Australia is a great hotspot of diversity of the genus Glycine [21].

Populations of Australian indigenous Glycine species are distributed all over the country and are the wild relatives of the economically important soybean crop [17, 21, 22]. Due to the inhospitable conditions of most areas growing indigenous Glycine in Australia, bioprospecting their genomes may help to understand and improve the adaptation of soybean to climate change [21]. In addition, to investigate the diversity of rhizobia symbionts of indigenous Glycine species in soils of Western Australia should provide valuable information for biotechnological applications. Here, we report a polyphasic study with three lineages of Bradyrhizobium isolated from Glycine clandestina, G. tabacina and G. max that resulted in the description of three new species.

Isolation and ecology

Strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T were isolated from root nodules of three different species, G. clandestina JC Wendl [23], G. tabacina (Labill.) Benth [24] and G. max, respectively, used as trap plants in Western Australian soil, as previously reported by our group [16]. Information about the strains used in this study as well as the sampling soil points are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

|

Species/strain name |

Other nomenclatures |

Original host species |

Geographical origin |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bradyrhizobium agreste CNPSo 4010T |

WSM 4802T=LMG 31645 |

Glycine clandestina |

Kununurra, Australia |

Helene et al. [16] |

|

Bradyrhizobium glycinis CNPSo 4016T |

WSM 4801T=LMG 31649T |

Glycine tabacina |

Kununurra, Australia |

Helene et al. [16] |

|

Bradyrhizobium diversitatis CNPSo 4019T |

WSM 4799T=LMG 31650T |

Glycine max |

Nambung, Australia |

Helene et al. [16] |

|

Bradyrhizobium fredereickii CNPSo 3426T |

USDA 10052T=U686T=CL 20T |

Chamaecrista fasciculata |

Missouri, USA |

Urquiaga et al. [38] |

|

Bradyrhizobium liaoningense LMG 18230T |

DSM 24092T=CECT 4845T=USDA 3622T |

Glycine max |

China |

Xu et al. [9] |

|

Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T |

CFNEB 101T=CIP 108027T=NBRC 100594T |

Lespedeza species |

China |

Yao et al. [59] |

The strains are deposited at the Diazotrophic and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria Culture Collection of Embrapa Soja (WFCC Collection No. 1213, WDCM Collection No. 1054), in Londrina, State of Parana, Brazil; at the Western Australian Soil Microbiology Gene Bank (WSM Culture Collection); at the Belgian Coordinated Collections of Microorganisms (BCCM/LMG); and in other culture collections.

The strains were short-term maintained on modified yeast extract–mannitol agar (YMA) medium [25] at 4 °C in a cold room and periodically cultured, while for long-term preservation the cultures were stored in modified-YM with 30 % glycerol (v/v) at −80 and −150 °C by cryopreservation, and lyophilized as previously described [26].

Phylogeny

Sequences of the 16S rRNA and of four housekeeping genes (dnaK, glnII, gyrB and recA), as well as of the symbiotic gene nodC were obtained from a previous study [16], and their accession numbers are shown in Table S1. Amplicons for the housekeeping gene atpD were obtained using the pair of primers TSatpDf (5′-TCTGGTCCGYGGCCAGGAAG-3′) and TSatpDr (5′-CGACACTTCCGARCCSGCCTG-3′), with the conditions described by Stepkowski et al. [27]. The PureLink kit (Invitrogen) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions for the purification of the PCR products, which were sequenced in an ABI 3500XL (Applied Biosystems) capillary sequencer analyzer, as described by Delamuta et al. [28]. All sequences were deposited at the GenBank database (NCBI) and the accession numbers are listed in parentheses in the phylogenetic trees and in Table S1. The complete sequences of housekeeping genes atpD, dnaK, glnII, gyrB, recA and rpoB were also retrieved from the genome of the type strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T in order to build a robust multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) phylogeny. Multiple sequence alignments were obtained with muscle [29] and the best evolutionary distance model was inferred by the lowest Bayesian information criterion scores [30] for maximum-likelihood (ML) reconstructions in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (mega) software version 7 [31]. The evolutionary models are described in the figure captions. The statistical support of the trees was estimated by bootstrap analysis [32] with 1000 re-samplings [33]. Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 was used as an outgroup for all phylogenies, except for the nodC tree. The sequences of housekeeping genes were concatenated with SeaView software version 4.7 [34] for the MLSA. Nucleotide identity was calculated with BioEdit software version 7.0.4.1 [35] for single and concatenated genes and the values are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Nucleotide identity among new lineages of Bradyrhizobium and closely related species, based on the sequences of single and concatenated housekeeping genes (atpD, dnaK, glnII, gyrB, recA and rpoB) and the 16S rRNA

|

Nucleotide identity (%) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Strains |

MLSA (five genes) |

MLSA (six genes) |

16S rRNA |

atpD |

dnaK |

glnII |

gyrB |

recA |

rpoB |

|

Bradyrhizobium agreste CNPSo 4010T |

|||||||||

|

B. glycinis CNPSo 4016T |

97.2 |

97.5 |

100 |

97.7 |

98.1 |

97.4 |

96.8 |

95.5 |

98.6 |

|

B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T |

96.4 |

96.9 |

99.6 |

94.9 |

99 |

95.8 |

95.3 |

95.8 |

98 |

|

B. liaoningense LMG 18230T |

95.3 |

95.3 |

99.6 |

94.1 |

95.9 |

94.6 |

94.4 |

94.7 |

97.8 |

|

B. diversitatis CNPSo 4019T |

95.1 |

95.3 |

99.6 |

94.1 |

95.9 |

94.4 |

94.8 |

93.8 |

97.5 |

|

B. frederickii CNPSo 4026T |

93.6 |

94.7 |

99.5 |

94.6 |

95.4 |

93.8 |

91.3 |

93.8 |

95.6 |

|

|

Bradyrhizobium glycinis CNPSo 4016T |

||||||||

|

B. agreste CNPSo 4010T |

97.2 |

97.5 |

100 |

97.7 |

98.1 |

97.4 |

96.8 |

95.5 |

98.6 |

|

B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T |

96.1 |

97.1 |

99.6 |

94.1 |

98.1 |

95.8 |

94.1 |

96.3 |

98.3 |

|

B. diversitatis CNPSo 4019T |

95.2 |

95.1 |

99.6 |

93.9 |

96.8 |

94.8 |

93.9 |

94.7 |

97.2 |

|

B. liaoningense LMG 18230T |

94.9 |

95.1 |

99.6 |

94.1 |

96.8 |

94.2 |

93.9 |

94.4 |

97 |

|

B. frederickii CNPSo 4026T |

93.6 |

94.5 |

99.5 |

95.1 |

95 |

94.2 |

90.7 |

93.8 |

95.9 |

|

|

Bradyrhizobium diversitatis CNPSo 4019T |

||||||||

|

B. liaoningense LMG 18230T |

97.6 |

97.8 |

100 |

96.9 |

98.6 |

94.8 |

98.1 |

98.6 |

99.1 |

|

B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T |

95.4 |

95.3 |

99.5 |

93.4 |

95.9 |

94.4 |

94.4 |

95.5 |

97.8 |

|

B. glycinis CNPSo 4016T |

95.2 |

95.1 |

99.6 |

94.1 |

95.9 |

94.4 |

94.8 |

93.8 |

97.5 |

|

B. agreste CNPSo 4010T |

95.1 |

95.3 |

99.6 |

93.9 |

96.8 |

94.8 |

93.9 |

94.7 |

97.2 |

|

B. frederickii CNPSo 4026T |

94.8 |

95.7 |

99.7 |

95.4 |

96.3 |

93.8 |

93.9 |

94.7 |

97 |

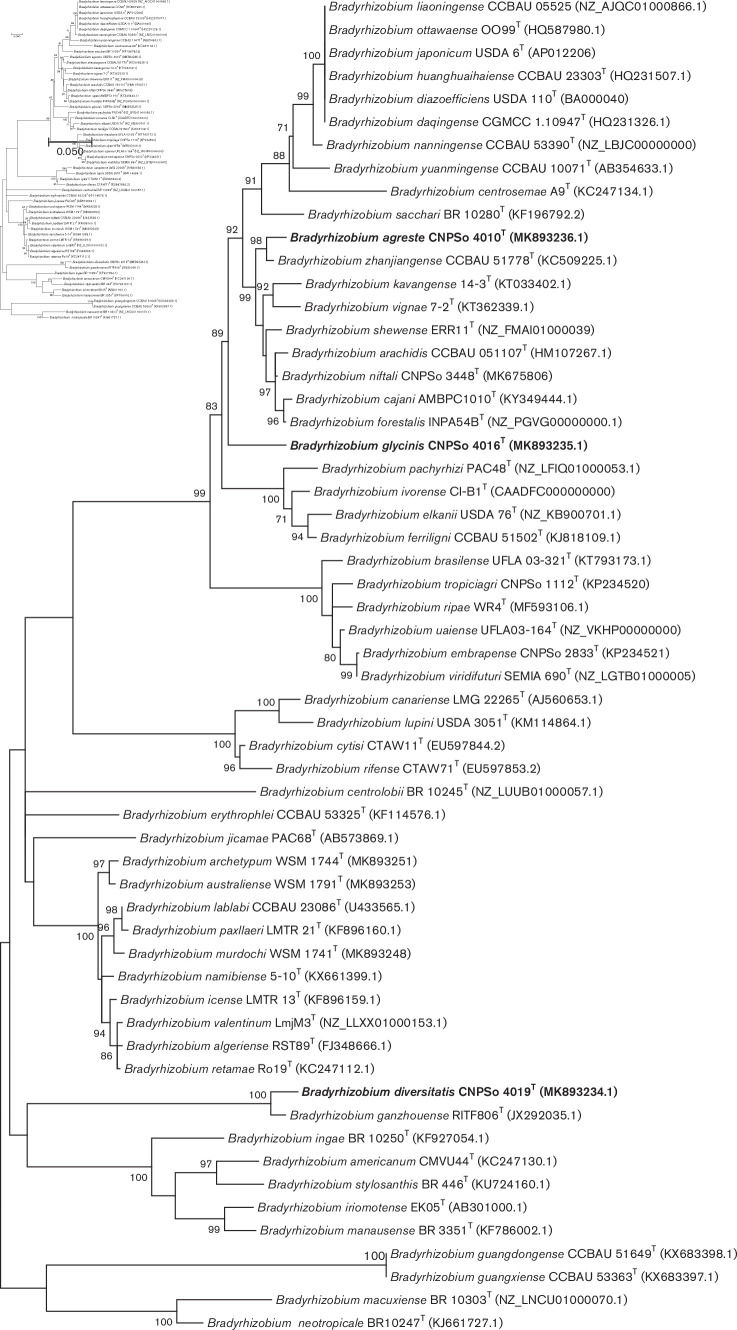

The 16S rRNA phylogeny traditionally splits the genus Bradyrhizobium into two well-supported superclades, B. japonicum and B. elkanii [36–38]. We included sequences of all described Bradyrhizobium species described at the time of writing and the three strains from our study fit into the B. japonicum superclade; strains CNPSo 4010T and CNPSo 4016T showed higher relatedness with B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T (99.6 % of similarity), whereas the CNPSo 4019T showed 100 % similarity to B. liaoningense LMG 18230T and 99.8 % to B. daqingense CGMCC 1.10947T (Fig. 1). The nucleotide identity values of the 16S rRNA genes among strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T ranged from 99.6 to 100% (Table 2). Considering the threshold of 98.65 % for species boundary suggested by Kim et al. [39], these results corroborate that the 16S rRNA gene provides limited taxonomic information in the genus Bradyrhizobium [15, 40–42].

Fig. 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny based on 16S rRNA alignment (1312 bp), using the T92 (Tamura three-parameter+G+I) model by mega version 7. Accession numbers are indicated in parentheses and in Table S1. The novel species are shown in bold. Bootstrap values >70 % are indicated at the nodes. Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 was used as an outgroup. Bar indicates two substitutions per 100 nucleotide positions.

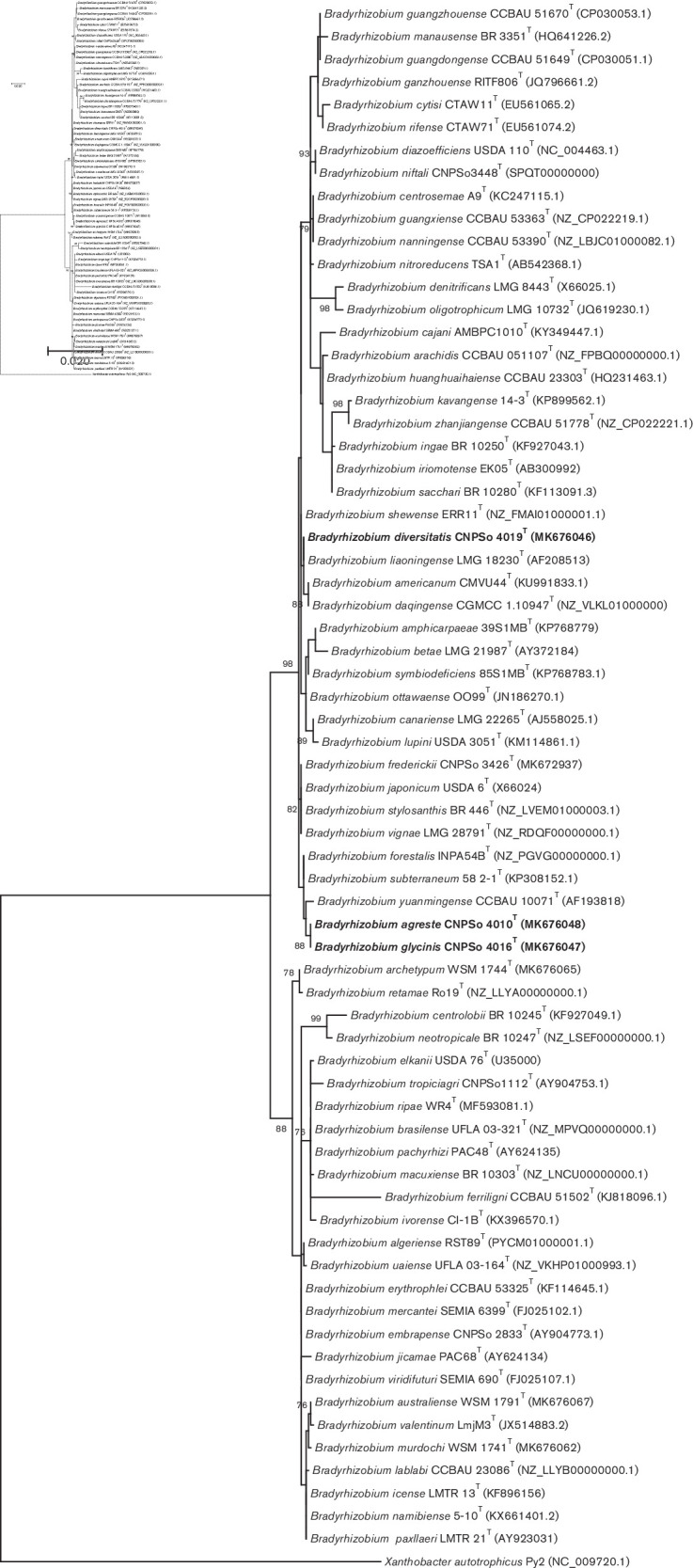

In the analysis of housekeeping genes, it is important to verify each single phylogeny to detect congruence with the 16S rRNA phylogeny and possible events of horizontal gene transfer and recombination [36, 43]. Therefore, single phylogenies of the genes atpD (398 bp), dnaK (221 bp), glnII (504 bp), gyrB (553 bp), recA (360 bp) and rpoB (371 bp) were built and are shown in Figs S1–S6 (available in the online version of this article). All phylogenies of single housekeeping genes clustered the strains from this study in clades separated from all described Bradyrhizobium species. However, some differences in the topology of the trees were verified on atpD (Fig. S1) and glnII (Fig. S3) phylogenies. The well-supported B. japonicum and B. elkanii superclades were not detected in the atpD phylogeny, as previously reported by Menna et al. [36]. Therefore, in order to improve the phylogenetic information of strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T, two alignments of concatenated housekeeping genes were performed for the MLSA; the first including dnaK+glnII+gyrB+recA+rpoB genes (2009 bp), and the second with complete sequences of atpD+dnaK+ glnII+gyrB+recA+rpoB genes (11 704 bp), and they are shown in Figs 2 and S7, respectively. The resulting concatenated phylograms maintained the main groups of strains observed in the 16S rRNA phylogeny, but improved the species delineation. Also, the similar topology of both MLSA trees demonstrated that this approach represents a reliable buffer against possible events of recombination at a single locus [44].

Fig. 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny based on alignment of dnaK+glnII+gyrB+recA+rpoB concatenated genes (2009 bp), using the GTR (general time reversible)+G+I model by mega version 7. Accession numbers are indicated in Table S1. The novel species are shown in bold. Bootstrap values >70 % are indicated at the nodes. Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 was used as an outgroup. Bar indicates five substitution per 100 nucleotide positions.

In the MLSA with five housekeeping genes (Fig. 2), strains CNPSo 4010T and CNPSo 4016T remained in a consistent cluster with 99 % bootstrap support, with B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T as the closest species with 96.4 and 96.1 % nucleotide identity, respectively (Fig. 2, Table 2). Concerning strain CNPSo 4019T, B. liaoningense LMG 18230T was the closest species with 99 % bootstrap support and 97.6 % similarity; another close species was B. frederickii CNPSo 3426T, sharing 94.8 % nucleotide identity. In addition, the nucleotide identity values among strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T ranged from 95.1 to 97.2 %.

Based on an MLSA with five housekeeping genes, Durán et al. [45] proposed the threshold of 97 % similarity for Bradyrhizobium species delineation. Even though the strains of this study showed nucleotide identity values slightly above this threshold in the MLSA, other species also shared nucleotide identity values higher than 97 %; for example, B. amphicarpaeae 39S1MBT and B. symbiodeficiens 85S1MBT (97.1 %), B. elkanii USDA 76T and B. pachyrhizi PAC 48T (97.5 %), B. elkanii USDA 76T and B. brasilense UFLA03-321T (97.6 %) (data not shown). Recently, also in studies with Bradyrhizobium, Klepa et al. [15], Helene et al. [46] and Fossou et al. [47] reported values higher than 97 % when considering five concatenated housekeeping genes. Therefore, as the nucleotide identity is a mathematic parameter and does not take into account specific mutations on gene sequences, we suggest that the threshold of Bradyrhizobium species delineation should be revised.

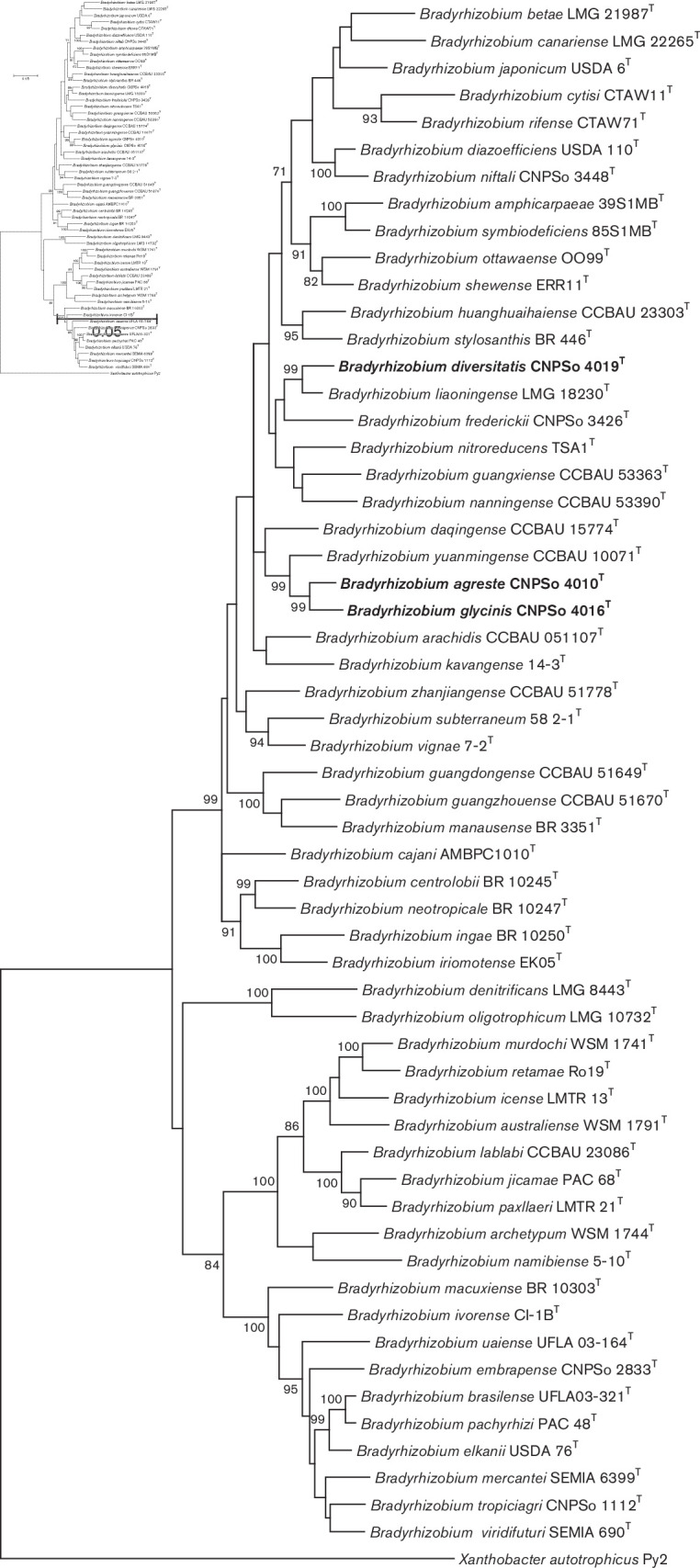

The symbiotic process between rhizobia and legumes relies on a complex molecular signal exchange that activates several genes responsible for nodule development [48–50]. Phylogeny of nodulation genes does not elucidate the taxonomic status; however, it is important to reveal the evolutionary history of symbiotic relationships, host-range specificity and symbiovar definitions [3, 28, 46, 51, 52]. In this study, the nodC gene analysis revealed that CNPSo 4010T from G. clandestina clustered in a well-supported clade with B. zhanjiangense CCBAU 51778T isolated from nodules of Arachis hypogaea in southeast China [53], CNPSo 4019T from G. max clustered with 100 % bootstrap support with B. ganzhouense RITF806T isolated from nodules of Acacia melanoxylon grown in China [54]; whereas CNPSo 4016T, isolated from G. tabacina, occupied an isolated position (Fig. 3). Note that the phylogenetic position of each of the three strains in the nodC tree was different. Comparing the core 16S rRNA and housekeeping genes with the nodC gene phylogenies, a different evolutionary pattern was detected in symbiotic phylogeny, suggesting different evolutionary histories, confirming previous reports of other species within the genus Bradyrhizobium [16, 28, 51].

Fig. 3.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny based on nodC alignment (426 bp), using the T92 (Tamura three-parameter+G+I) model by mega version 7. Accession numbers are indicated in parentheses. The novel species are shown in bold. Bootstrap values >70 % are indicated at the nodes. Bar indicates five substitutions per 100 nucleotide positions.

Genome features

Total DNA of strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T was extracted and used to reconstruct the sequence libraries according to the manufacturer’s protocol of Nextera XT kit. The genome sequencing was performed using the MiSeq platform (Illumina) at Embrapa Soja. De novo sequence assemblies were carried out by A5-MiSeq pipeline version 20 140 604. The genomes were annotated with RAST version 2.0 [55], using default parameters. The draft genome of CNPSo 4010T (JACCHP000000000) presented about 7 877 331 bp with 75 contigs and an N50 value of 251 874 bp. The genome size of CNPSo 4016T (JACCHQ000000000) was estimated at 7 794 411 bp, containing 83 contigs and an N50 value of 202 190 bp. The genome of CNPSo 4019T (JACEGD000000000) was estimated at 8 450 368 bp, with 133 contigs and an N50 value of 198 871 bp. The sequence coverages of genomes CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T were estimated at 95-, 91-, and 94-fold, respectively. Coding DNA sequences were identified as 7883 for CNPSo 4010T, as 7987 for CNPSo 4016T and 8603 for CNPSo 4019T.

Genomic-based measurements of similarity simplify and ensure robust data for microbial taxonomy as a replacement for the traditional DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) technique [56, 57]. We used average nucleotide identity (ANI) and the digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) analyses for species delineation considering the suggested cut-off values of 95–96 and 70 %, respectively [56, 58, 59]. The genomes of strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T were compared with the closest related strains according to the phylogenetic analyses: B. frederickii CNPSo 3426T (SPQS00000000), B. liaoningense LMG 18230T (project ID: 1052895 - JGI) and B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T (FMAE01000000). ANI values were calculated using the ANI calculator [60] and the dDDH values were estimated with the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) version 2.1 [61], using the recommended ‘formula 2’ (identities/HSP length). Strains CNPSo 4010T and CNPSo 4016T shared 94.18 % of ANI and 55.50 % of dDDH to each other and both strains showed values lower than 93.32 % for ANI and 51.80 % for dDDH when compared with B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T isolated from nodules of Lespedeza species plants in China [62] (Table 3). The ANI and dDDH values between CNPSo 4019T and B. liaoningense LMG 18230T isolated from nodules of G. max grown in China [9] were of 94.97 and 59.80 %, respectively. The values below the threshold for species delineation recorded for the three Australian strains isolated from Glycine species confirm that they belong to new species.

Table 3.

ANI and dDDH values among new lineages of Bradyrhizobium and closely related Bradyrhizobium species

|

CNPSo 4010T |

CNPSo 4016T |

Bradyrhizobium diversitatis CNPSo 4019T |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Strains |

ANI % |

dDDH % |

ANI % |

dDDH % |

ANI % |

dDDH % |

|

B. fredereickii CNPSo 3426T |

88.20 |

35.80 |

88.13 |

35.60 |

88.66 |

36.90 |

|

B. liaoningense LMG 18230T (JGI Project Id: 1052895) |

89.20 |

38.40 |

89.19 |

38.60 |

94.97 |

59.80 |

|

B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T |

92.62 |

48.60 |

93.32 |

51.80 |

89.21 |

38.40 |

|

B. agreste CNPSo 4010T |

– |

– |

94.18 |

55.50 |

89.25 |

38.30 |

|

B. glycinis CNPSo 4016T |

94.18 |

55.50 |

– |

– |

89.28 |

38.50 |

|

B. diversitatis CNPSo 4019T |

89.26 |

38.40 |

89.28 |

38.40 |

– |

– |

The genome G+C contents were calculated using the seed platform [55] and estimated to be 63.8, 63.7 and 63.8 mol% for CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T, respectively.

Genomic diversity at strain level was determined by BOX-PCR, using BOX-A1R primer (5′-CTACGGCAAGGCGACGCTGACG-3′) [63], with the conditions described by Chibeba et al. [64]. The BOX-PCR profiles of strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T and the most related species based on the MLSA, B. liaoningense LMG 18230T and B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T, were analysed and compared with the Bionumerics software version 7.6 (Applied Mathematics) using the UPGMA (unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean) [65] and the Jaccard coefficient [66], with 2 % tolerance. The profiles shared less than 50 % similarity among the strains of this study, confirming high diversity, and also varied in relation to the closest Bradyrhizobium species (Fig. S8).

Therefore, this is the first study describing novel species isolated from wild Glycine (G. clandestina and G. tabacina) indigenous to Australia, which are usually neglected compared to the economically important soybean crop. Even though these wild species are not cultivated, they are considered as a secondary genetic source for desirable agronomic traits such as drought tolerance and disease resistance, due the closeness to soybean [17, 20, 22]. Considering the symbiosis with compatible and well-adapted Bradyrhizobium, the nodulated wild Glycine may represent an interesting option to restore degraded habitats in Australia.

The phylogenetic relationships of the genus Glycine have not yet been fully explained. Whereas G. max was domesticated in China around 5000 years ago, through the crossing of wild soybean species [67–69], Australia harbours most of the wild species of the genus Glycine [17–21]. Some events during the Earth's evolution have been hypothesized to explain the diversification of these legumes. After the Pangea breakup, the Gondwana supercontinent was formed, connecting Australia and Antarctica; these landmasses separated and Australia moved northwards close to Asia. This moment possibly allowed the successfully entry of Asian legumes in Australia and, consequently, their symbionts [14, 70–72].

Taking into account that China is the original centre of soybean, the region might also be a diversification centre for compatible rhizobia [73–75]. The high similarity of CNPSo 4010T and CNPSo 4016T to B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T and CNPSo 4019T to B. liaoningense LMG 18230T may be related to dispersal events. Although B. yuamingense CCBAU 10071T was the original symbiont of Lespezeda species in China [62], many strains of this species have been isolated from soybean in Asian soils [74–76]. Also, B. liaoningense is a widespread soybean symbiont in India and China [9, 77, 78]. Therefore, our findings support the hypothesis of legume and symbionts exchange between Asian and Australian continents.

Phenotypic characterization

Several morphophysiological evaluations were performed and compared with strains CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T and closest species B. liaoningense LMG 18230T and B. yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T. Except where indicated, the tests were assessed on modified-YMA medium at 28 °C [25]. Colony morphology was analysed using Congo red and acid and alkaline reaction using bromothymol blue after 7–10 days of growth. In order to evaluate growth under different conditions, the strains were cultured with 1 % NaCl, at 37 °C, on Luria–Bertani (LB) medium, at pH 4.0 and 8.0, adapted from Hungria et al. [79]. The urease activity was tested using 2 % urea and phenol red as indicator. Carbohydrate metabolism was detected by the API 50CH kit platform (bioMérieux), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and using modified-YM-minus-mannitol with bromothymol blue. Tolerance of antibiotics was determined by the disc-diffusion technique proposed by Bauer et al. [80] using ampicillin (10 µg), bacitracin (10 U), cefuroxime (30 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg), neomycin (30 µg), penicillin (10 U), streptomycin (10 µg), tetracycline (30 µg) and erythromycin (15 µg). All tests were conducted in duplicate.

In general, the phenotypic results are in agreement with those commonly found in the genus Bradyrhizobium. However, it is worth mentioning some unusual features detected in this study: CNPSo 4010T showed a neutral reaction on modified-YMA with bromothymol blue as indicator and the three strains from this study presented optimal growth on modified-YMA at 37 °C in 3–4 days, indicating a possible mechanism of high temperature tolerance. CNPSo 4019T was able to grow in a large pH range, pH 4.0–8.0, while strain CNPSo 4016T grew well at pH 8.0. Carbohydrate metabolism by API 50CH was heterogeneous among the strains and revealed slightly incongruences with the universal culture medium used to grow rhizobia (YMA), since the CNPSo strains weakly used d-mannitol and also glycerol, another C source commonly used for this culture media. Interestingly, CNPSo 4016T was positive or weak for metabolism of all carbohydrate sources available on the kit. Although our findings revealed different metabolic features, the phenotypic characteristics are generally encoded by the accessory genome, being unstable over time. Also, they may present different results according to the laboratory conditions [81, 82]. The differential phenotypical features among the strains from this study and closest species are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distinctive phenotypical properties of new lineages of Bradyrhizobium and closely related strains

Strains: 1, Bradyrhizobium agreste CNPSo 4010T; 2, Bradyrhizobium glycinis CNPSo 4016T; 3, Bradyrhizobium diversitatis CNPSo 4019T; 4, Bradyrhizobium liaoningense LMG 18230T; 5, Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense CCBAU 10071T. Data are evaluated as: +, growth; w, weakly positive; −, no growth. na, No data available.

|

Characteristic |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4* |

5† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Carbon source utilization: |

|

||||

|

Erythritol |

− |

w |

− |

− |

− |

|

d-Arabinose |

w |

+ |

w |

+ |

w |

|

l-Arabinose |

w |

w |

w |

+ |

+ |

|

d-Ribose |

w |

w |

w |

+ |

+ |

|

d-Xylose |

w |

+ |

w |

+ |

+ |

|

l-Xylose |

w |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

d-Adonitol |

− |

w |

− |

− |

− |

|

Methyl β-d-xylopyranoside |

w |

w |

w |

− |

w |

|

d-Galactose |

w |

w |

− |

w |

w |

|

d-Fructose |

w |

w |

− |

− |

w |

|

l-Sorbose |

w |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

l-Rhamnose |

− |

w |

w |

w |

w |

|

Dulcitol |

− |

− |

w |

− |

− |

|

Inositol |

− |

w |

− |

− |

− |

|

d-Mannitol |

w |

w |

w |

− |

w |

|

d-Sorbitol |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Methyl α-d-mannopyranoside |

− |

− |

w |

− |

− |

|

Methyl α-d-glusopyranoside |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

N-Acetylglucosamine |

w |

− |

w |

− |

− |

|

Amygdalin |

− |

+ |

w |

− |

− |

|

Arbutin |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Aesculin ferric citrate |

w |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Salicin |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Cellobiose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Maltose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

w |

|

Lactose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Melibiose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Sucrose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Trehalose |

− |

w |

w |

w |

− |

|

Inulin |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Melezitose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Raffinose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Glycogen |

+ |

w |

+ |

+ |

− |

|

Xylitol |

− |

w |

− |

− |

− |

|

Gentiobiose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

Turanose |

− |

+ |

w |

− |

− |

|

d-Lyxose |

+ |

+ |

w |

+ |

+ |

|

d-Tagatose |

− |

w |

w |

− |

− |

|

d-Fucose |

w |

+ |

w |

+ |

+ |

|

d-Arabitol |

w |

w |

w |

w |

− |

|

l-Arabitol |

− |

+ |

− |

− |

− |

|

Potassium gluconate |

− |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

|

Potassium 2-ketogluconate |

+ |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

|

Potassium 5-ketogluconate |

w |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

|

Enzymatic activity: |

|

||||

|

Urease |

w |

w |

+ |

+ |

na |

|

Growth at/in: |

|

||||

|

pH 4 |

w |

w |

+ |

+ |

− |

|

pH 8 |

w |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Alkaline reaction |

w |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

37 °C |

+ (4 days) |

+ (4 days) |

+ (3 days) |

− |

+ |

|

Tolerance to antibiotics: |

|

||||

|

Ampicillin (10 µg) |

+ |

− |

+ |

− |

w |

|

Bacitracin (10 U) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

na |

|

Erythromycin (15 µg) |

− |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Neomycin (30 µg) |

w |

w |

+ |

− |

− |

|

Streptomycin (10 µg) |

− |

− |

− |

− |

+ |

|

Tetracycline (30 µg) |

w |

− |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Nodulation and nitrogen fixation assays were carried out in Leonard jars with soybean commercial cultivar BRASMAX Potência RR and with the promiscuous papilionoid siratro (Macroptilium atropurpureum). Each jar was sterilized with sand, vermiculite (2 : 1, v:v) and the N-free nutrient solution described by Broughton and Dilworth [83]. The strains were cultured in modified-YM medium [25] and inoculated on the seeds (1 ml) after planting. The plants grew under controlled glasshouse conditions for 30 days. All strains were able to form effective red colour nodules with siratro but only strain CNPSo 4019T was able to effectively nodulate soybean, its original host (Fig. S9).

Therefore, the phylogenetic, genomic and phenotypic data accomplished in this study support the proposed descriptions of the novel species Bradyrhizobium agreste sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium glycinis sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium diversitatis sp. nov., isolated from three different Glycine species, for which the type strains are CNPSo 4010T, CNPSo 4016T and CNPSo 4019T, respectively.

Description of Bradyrhizobium agreste sp. nov.

Bradyrhizobium agreste (a.gres'te. L. neut. adj. agreste, wild, referring to the importance of isolation from wild species, such as the Glycine clandestina from this study).

Cells are Gram-stain-negative, aerobic and non-spore-forming. Colonies on modified-YMA medium at pH 6.8–7.0 and Congo red are slightly pink, less than 1 mm in diameter, circular, opaque, with low mucus production and a gummy consistency after 7 days of growth at 28 °C. The strain shows a neutral reaction on modified-YMA with bromothymol blue as indicator and weak urease activity. CNPSo 4010T shows weak growth at pH 4.0 and 8.0. The strain is able to grow at 37 °C for 4 days, but unable to grow on solid LB medium and modified-YMA containing 1 % NaCl. With respect to carbon sources in the API test, the strain is able to use starch, glycogen, d-se, l-fucose and potassium 2-ketogluconate; weakly uses glycerol, d-arabinose, l-arabinose, d-ribose, d-xylose, l-xylose, methyl β-d-xylopyranoside, d-galactose, d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, l-sorbose, d-mannitol, N-acetylglucosamine, aesculin ferric citrate, d-fucose, d-arabitol and potassium 5-ketogluconate; does not use erythritol, d-adonitol, l-rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d-sorbitol, methyl α-d-mannopyranoside, methyl α-d-glucopyranoside, amygdalin, arbutin, salicin, cellobiose, maltose, lactose, melibiose, sucrose, trehalose, inulin, melezitose, raffinose, xylitol, gentiobiose, turanose, d-tagatose, l-arabitol and potassium gluconate. The strain is tolerant to the antibiotics ampicillin (10 µg), bacitracin (10 U), chloramphenicol (30 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg) and penicillin G (10 U), moderately sensitive to neomycin (30 µg) and tetracycline (30 µg) and sensitive to cefuroxime (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg) and streptomycin (10 µg). The strain is able to form effective nitrogen-fixing nodules with Macroptilium atropurpureum, but does not nodulate Glycine max.

The type strain, CNPSo 4010T (=WSM 4802T=LMG 31645T), was isolated from a nodule of Glycine clandestina in Kununurra, Australia. The DNA G+C content of strain CNPSo 4010T is 63.8 mol%.

Description of Bradyrhizobium glycinis sp. nov.

Bradyrhizobium glycinis (gly.ci’nis. N.L. gen. n. glycinis, of the genus Glycine, a genus that encompasses host plants of several Bradyrhizobium species, including this new species, isolated from G. tabacina).

Cells are Gram-stain-negative, aerobic and non-spore-forming. Colonies on modified-YMA medium at pH 6.8–7.0 and Congo red are slightly pink, less than 1 mm in diameter, circular, opaque and exhibit low mucus production with a gummy consistency after 7 days of growth at 28 °C. The strain shows an alkaline reaction on modified-YMA with bromothymol blue and weak urease activity. CNPSo 4016T shows weak growth at pH 4.0 but grows well at pH 8.0 and at 37 °C after 4 days. The strain is unable to grow on solid LB medium and modified-YMA containing 1 % NaCl. With respect to carbon sources in the API test, strain CNPSo 4016T is able to use d-arabinose, amygdalin, aesculin ferric citrate, starch, turanose, d-ose, d-fucose, l-fucose, l-arabitol, potassium gluconate, potassium 2-ketogluconate and potassium 5-ketogluconate; weakly uses glycerol, erythritol, l-arabinose, d-ribose, d-xylose, l-xylose, d-adonitol, methyl β-d-xylopyranoside, d-galactose, d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, l-sorbose, l-rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d-mannitol, d-sorbitol, methyl α-d-mannopyranoside, methyl α-d-glucopyranoside, N-acetylglucosamine, arbutin, salicin, cellobiose, maltose, lactose, melibiose, sucrose, trehalose, inulin, melezitose, raffinose, glycogen, xylitol, gentiobiose, d-tagatose and d-arabitol. The strain is tolerant to bacitracin (10 U), chloramphenicol (30 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg) and penicillin G (10 U), moderately sensitive to neomycin (30 µg) and sensitive to ampicillin (10 µg), cefuroxime (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), streptomycin (10 µg) and tetracycline (30 µg). The strain is able to form effective nitrogen-fixing nodules with Macroptilium atropurpureum but does not nodulate Glycine max.

The type strain CNPSo 4016T (=WSM 4801T=LMG 31649T) was isolated from a nodule of Glycine tabacina in Kununurra, Australia. The DNA G+C content of strain CNPSo 4016T is 63.7 mol%.

Description of Bradyrhizobium diversitatis sp. nov.

Bradyrhizobium diversitatis (di.ver.si.ta’tis. L. fem. n. diversitas diversity, N.L. gen. n. diversitatis, of diversity, referring to the importance of studies on microbial diversity revealing, as in the case of this study, genetic richness of Bradyrhizobium isolated from Glycine max).

Cells are Gram-stain-negative, aerobic and non-spore-forming. Colonies on modified-YMA medium at pH 6.8–7.0 and Congo red are slightly pink, less than 1 mm in diameter, circular, opaque and exhibit low mucus production with a gummy consistency after 7 days of growth at 28 °C. The strain shows alkaline reaction on modified-YMA with bromothymol blue, is urease-positive and able to grow at pH 4.0 and 8.0. CNPSo 4019T is able to grow at 37 °C after 3 days. The strain is unable to grow on solid LB medium and modified-YMA containing 1 % NaCl. With respect to carbon sources in the API test, strain CNPSo 4019T is able to use l-xylose, aesculin ferric citrate, starch, glycogen, l-fucose, potassium gluconate, potassium 2-ketogluconate, and potassium 5-ketogluconate; weakly uses glycerol, d-arabinose, l-arabinose, d-ribose, d-xylose, d-adonitol, methyl β-d-xylopyranoside, d-glucose, d-mannose, l-sorbose, l-rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d-mannitol, d-sorbitol, methyl α-d-mannopyranoside, methyl α-d-glucopyranoside, N-acetylglucosamine, amygdalin, arbutin, salicin, cellobiose, maltose, lactose, melibiose, sucrose, trehalose, inulin, melezitose, raffinose, gentiobiose, turanose, d-lyxose, d-tagatose, d-fucose and d-arabitol; does not use erythritol, d-galactose, d-fructose, xylitol and l-arabitol. The strain is tolerant to the antibiotics ampicillin (10 µg), bacitracin (10 U), chloramphenicol (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg), neomycin (30 µg), penicillin G (10 U) and tetracycline (30 µg); and is sensitive to cefuroxime (30 µg) and streptomycin (10 µg). The strain is able to form nitrogen-fixing nodules with Macroptilium atropurpureum and Glycine max.

The type strain, CNPSo 4019T (=WSM 4799T=LMG 31650T), was isolated from a nodule of Glycine max in Nambung, Australia. The DNA G+C content of strain CNPSo 4019T is 63.8 mol%.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

Partially financed by INCT – Plant-Growth Promoting Microorganisms for Agricultural Sustainability and Environmental Responsibility (CNPq 465133/2014-4, Fundação Araucária-STI 043/2019, CAPES).

Acknowledgements

M. S. K. acknowledges a PhD fellowship from CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Finance Code 001) and L. C. R. H. acknowledges a post-doctoral fellowship from CAPES (INCT). M. H. acknowledges a research fellow from CNPq (Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development). The authors thank the brilliant Dr Aharon Oren (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) and his wonderful knowledge of Latin and Greek, for help with the specific epithet proposals of these species.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANI, average nucleotide identity; BNF, biological nitrogen fixation; dDDH, digital DNA–DNA hybridization; DDH, DNA–DNA hybridization; GGDC, Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator; LB, Luria–Bertani; ML, maximum-likelihood; MLSA, multilocus sequence analysis; NI, nucleotide identity; UPGMA, unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean algorithm; YMA, yeast–mannitol agar.

One supplementary table and nine supplementary figures are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Dixon R, Kahn D. Genetic regulation of biological nitrogen fixation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:621–631. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Bruijn FJ. Biological nitrogen fixation. In: Lugtenberg B, editor. Principles of Plant-Microbe Interactions: Microbes for Sustainable Agriculture. 1st ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 1–448. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peix A, Ramírez-Bahena MH, Velázquez E, Bedmar EJ. Bacterial associations with legumes. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2015;34:17–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mus F, Crook MB, Garcia K, Garcia Costas A, Geddes BA, et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and the challenges to its extension to nonlegumes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:3698–3710. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01055-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ormeño-Orrillo E, Hungria M, Martinez-Romero E. Dinitrogen-fixing prokaryotes. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong E, Stackebrandt E, Lory S, Thompson F, editors. The Prokaryotes: Prokaryotic Physiology and Biochemistry. 4th ed. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2013. pp. 427–451. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bashan Y, de-Bashan LE, Prabhu SR, Hernandez JP. Advances in plant growth-promoting bacterial inoculant technology: formulations and practical perspectives (1998-2013) Plant Soil. 2014;378:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hungria M, Loureiro MF, Mendes IC, Campo RJ, Graham PH. Inoculant preparation, production and application. In: Werner D, Newton WE, editors. Nitrogen Fixation in Agriculture, Forestry, Ecology, and the Environment. 4th ed. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2005. pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hungria M, Mendes IC. Nitrogen fixation with soybean: the perfect symbiosis? In: de Bruijn FJ, editor. Biological Nitrogen Fixation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2015. pp. 1009–1023. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu LM, Ge C, Cui Z, Li J, Fan H. Bradyrhizobium liaoningense sp. nov., isolated from the root nodules of soybeans. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:706–711. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang JY, Wang R, Zhang YM, Liu HC, Chen WF, et al. Bradyrhizobium daqingense sp. nov., isolated from soybean nodules. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:616–624. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.034280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu X, Cloutier S, Tambong JT, Bromfield ESP. Bradyrhizobium ottawaense sp. nov., a symbiotic nitrogen fixing bacterium from root nodules of soybeans in Canada. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:3202–3207. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.065540-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menna P, Hungria M, Barcellos FG, Bangel EV, Hess PN, et al. Molecular phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA gene of elite rhizobial strains used in Brazilian commercial inoculants. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2006;29:315–332. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hungria M, Menna P, Marçon Delamuta JR. Bradyrhizobium, the ancestor of all rhizobia: phylogeny of housekeeping and nitrogen-fixation genes. In: Bruijn FJ, editor. Biological Nitrogen Fixation. New Jersey: Wiley, Sons, Inc; 2015. pp. 191–202. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprent JI, Ardley J, James EK. Biogeography of nodulated legumes and their nitrogen-fixing symbionts. New Phytol. 2017;215:40–56. doi: 10.1111/nph.14474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klepa MS, Urquiaga MCdeO, Somasegaran P, Delamuta JRM, Ribeiro RA, et al. Bradyrhizobium niftali sp. nov., an effective nitrogen-fixing symbiont of partridge pea [Chamaecrista fasciculata (Michx.) Greene], a native caesalpinioid legume broadly distributed in the USA. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019;69:3448–3459. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferraz Helene LC, O'Hara G, Hungria M, Helene LCF, O’Hara G. Characterization of Bradyrhizobium strains indigenous to Western Australia and South Africa indicates remarkable genetic diversity and reveals putative new species. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2020;43:126053. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2020.126053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pueppke SG. Nodulating associations among rhizobia and legumes of the genus Glycine subgenus Glycine . Plant an. 1988;109:189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hungria M, Franchini JC, Campo RJ, Graham PH. The importance of nitrogen fixation to soybean cropping in South America. In: Werner D, Newton WE, editors. Nitrogen Fixation in Agriculture, Forestry, Ecology, and the Environment. 4th ed. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2005. pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeil BEA, Craven LAB, Brown A, Murray BGC, Doyle JJA. Three new species of northern Australian Glycine (Fabaceae, Phaseolae), G. gracei, G. montis-douglas and G. syndetika . Aust Syst Bot. 2006;19:245–258. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermann FJ. A Revision of the Genus Glycine and Its Immediate Allies. Washiton, DC: U.S.D.A. Agricultural Research Service; 1962. p. 79. p. [Google Scholar]

- 21.González-Orozco CE, Brown AH, Knerr N, Miller JT, Doyle JJ. Hotspots of diversity of wild Australian soybean relatives and their conservation in situ. Conserv Genet. 2012;13:1269–1281. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle JJ, Doyle JJ, Doyle JL, Rauscher JT, Brown AHD. Diploid and polyploid reticulate evolution throughout the history of the perennial soybeans (Glycine subgenus Glycine) New Phytol. 2003;161:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stajsic V. Flora of Victoria [Internet]. Glycine clandestina J.C.Wendl. Twining Glycine. 2018 [cited 2020 Oct 27]. Available from: https://vicflora.rbg.vic.gov.au/flora/taxon/4441818f-b0dc-40a4-b2ec-268db551d025

- 24.Herbarium Western Australia FloraBase—the Western Australian Flora. [Internet]. Glycine tabacina (Labill.) Benth. Glycine Pea. 1998 [cited 2020 Oct 27]. Available from: https://florabase.dpaw.wa.gov.au/browse/profile/3941

- 25.Hungria M, O’Hara GW, Zilli JE, Araujo RS, Deaker R, et al. Isolation and growth of rhizobia. In: Howieson JG, Dilworth MJ, editors. Working with Rhizobia. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agriculture Reserch (ACIAR); 2016. pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delamuta JRM, Ribeiro RA, Araújo JLS, Rouws LFM, Zilli Jerri Édson, et al. Bradyrhizobium stylosanthis sp. nov., comprising nitrogen-fixing symbionts isolated from nodules of the tropical forage legume Stylosanthes spp. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:3078–3087. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stepkowski T, Moulin L, Krzyzańska A, McInnes A, Law IJ, et al. European origin of Bradyrhizobium populations infecting lupins and serradella in soils of Western Australia and South Africa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7041–7052. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7041-7052.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delamuta JRM, Menna P, Ribeiro RA, Hungria M. Phylogenies of symbiotic genes of Bradyrhizobium symbionts of legumes of economic and environmental importance in Brazil support the definition of the new symbiovars pachyrhizi and sojae. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2017;40:254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edgar RC. Muscle: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Evol Genet Anal. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedges SB. The number of replications needed for accurate estimation of the bootstrap P value in phylogenetic studies. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:366–369. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–224. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall T. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menna P, Barcellos FG, Hungria M. Phylogeny and taxonomy of a diverse collection of Bradyrhizobium strains based on multilocus sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, ITS region and glnII, recA, atpD and dnaK genes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:2934–2950. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.009779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delamuta JRM, Ribeiro RA, Ormeño-Orrillo E, Melo IS, Martínez-Romero E, et al. Polyphasic evidence supporting the reclassification of Bradyrhizobium japonicum group Ia strains as Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:3342–3351. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.049130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferraz Helene LC, Marçon Delamuta JR, Augusto Ribeiro R, Ormeño-Orrillo E, Antonio Rogel M, et al. Bradyrhizobium viridifuturi sp. nov., encompassing nitrogen-fixing symbionts of legumes used for green manure and environmental services. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4441–4448. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M, Oh H-S, Park S-C, Chun J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:346–351. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.059774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delamuta JRM, Ribeiro RA, Ormeño-Orrillo E, Parma MM, Melo IS, et al. Bradyrhizobium tropiciagri sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium embrapense sp. nov., nitrogen-fixing symbionts of tropical forage legumes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4424–4433. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helene LCF, Delamuta JRM, Ribeiro RA, Hungria M. Bradyrhizobium mercantei sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing symbiont isolated from nodules of Deguelia costata (syn. Lonchocarpus costatus) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1827–1834. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urquiaga MCdeO, Klepa MS, Somasegaran P, Ribeiro RA, Delamuta JRM, et al. Bradyrhizobium frederickii sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing lineage isolated from nodules of the caesalpinioid species Chamaecrista fasciculata and characterized by tolerance to high temperature in vitro . Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019;69:3863–3877. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang J, Bromfield ESP, Rodrigue N, Cloutier S, Tambong JT. Microevolution of symbiotic Bradyrhizobium populations associated with soybeans in east North America. Ecol Evol. 2012;2:2943–2961. doi: 10.1002/ece3.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gevers D, Cohan FM, Lawrence JG, Spratt BG, Coenye T, et al. Opinion: Re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:733–739. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durán D, Rey L, Mayo J, Zúñiga-Dávila D, Imperial J, et al. Bradyrhizobium paxllaeri sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium icense sp. nov., nitrogen-fixing rhizobial symbionts of lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) in Peru. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:2072–2078. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.060426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helene LCF, Klepa MS, O'Hara G, Hungria M. Bradyrhizobium archetypum sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium australiense sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium murdochi sp. nov., isolated from nodules of legumes indigenous to Western Australia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:4623–4636. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fossou RK, Pothier JF, Zézé A, Perret X. Bradyrhizobium ivorense sp. nov. as a potential local bioinoculant for Cajanus cajan cultures in Côte d'Ivoire. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:1421–1430. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schultze M, Kondorosi A. Regulation of symbiotic root nodule development. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:33–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lloret L, Martínez-romero E. Evolución y filogenia de Rhizobium . Rev Latinoam Microbiol. 2005;47:43–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones KM, Kobayashi H, Davies BW, Taga ME, Walker GC. How rhizobial symbionts invade plants: the Sinorhizobium-Medicago model. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:619–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menna P, Hungria M. Phylogeny of nodulation and nitrogen-fixation genes in Bradyrhizobium: supporting evidence for the theory of monophyletic origin, and spread and maintenance by both horizontal and vertical transfer. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61:3052–3067. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.028803-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogel MA, Ormeño-Orrillo E, Martinez Romero E, Romero EM. Symbiovars in rhizobia reflect bacterial adaptation to legumes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2011;34:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li YH, Wang R, Sui XH, Wang ET, Zhang XX, et al. Bradyrhizobium nanningense sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium guangzhouense sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium zhanjiangense sp. nov., isolated from effective nodules of peanut in Southeast China. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2019;42:126002. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2019.126002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu JK, Dou YJ, Zhu YJ, Wang SK, Sui XH, et al. Bradyrhizobium ganzhouense sp. nov., an effective symbiotic bacterium isolated from Acacia melanoxylon R. Br. nodules. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:1900–1905. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.056564-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:206–214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chun J, Oren A, Ventosa A, Christensen H, Arahal DR, et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Lajudie PM, Andrews M, Ardley J, Eardly B, Jumas-Bilak E, et al. Minimal standards for the description of new genera and species of rhizobia and agrobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019;69:1852–1863. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, et al. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mahato NK, Gupta V, Singh P, Kumari R, Verma H, et al. Microbial taxonomy in the era of OMICS: application of DNA sequences, computational tools and techniques. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2017;110:1357–1371. doi: 10.1007/s10482-017-0928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez-R LM, Konstantinidis KT. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. Peer J Prepr. 2016;4:e1900v1 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk H-P, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao ZY, Kan FL, Wang ET, Wei GH, Chen WX. Characterization of rhizobia that nodulate legume species of the genus Lespedeza and description of Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:2219–2230. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-6-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Versalovic J, Schneider M, de BFJ, Lupski JR. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1994;5:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chibeba AM, Kyei-boahen S, Guimarães MF, Nogueira MA, Hungria M. Isolation, Characterization and Selection of Indigenous Bradyrhizobium Strains with Outstanding Symbiotic Performance to Increase Soybean Yields in Mozambique. Vol. 246. Agric Ecosyst Environ. Elsevier; 2017. pp. 291–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sneath P, Sokal R. Numerical Taxonomy: the Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. San Francisco: Freeman; 1973. p. 573. p. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jaccard P. The distribution of flora in the alpine zone. New Phytol. 1912;11:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hymowitz T. On the domestication of the soybean. Econ Bot. 1970;24:408–421. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hymowitx T, Newell CA. Taxonomy of the genus Glycine, domestication and uses of soybeans. Econ Bot. 1981;35:272–288. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruiz Sainz JE, Zhou JC, Rodriguez-Navarro D-N, Vinardell JM, Thomas-Oates JE. Soybean cultivation and BNF in China. In: Werner D, Newton WE, editors. Nitrogen Fixation in Agriculture, Forestry, Ecology, and the Environment. Springer; 2005. pp. 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hymowitz T, Singh RJ, Larkin RP. Long-distance dispersal: the case for the allopolyploid glycine tabacina (Labill.) Benth. and G. tomentella Hayata in the West-Central Pacific. Micronesica. 1990;23:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sniderman JMK, Jordan GJ. Extent and timing of floristic exchange between Australian and Asian rain forests. J Biogeogr. 2011;38:1445–1455. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buerki S, Forest F, Alvarez N. Proto-South-East Asia as a trigger of early angiosperm diversification. Bot J Linn Soc. 2014;174:326–333. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lie TA, Göktan D, Engin M, Pijnenborg J, Anlarsal E. Co-evolution of the legume-Rhizobium association. Plant Soil. 1987;100:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Man CX, Wang H, Chen WF, Sui XH, Wang ET, et al. Diverse rhizobia associated with soybean grown in the subtropical and tropical regions of China. Plant Soil. 2008;310:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li QQ, Wang ET, Zhang YZ, Zhang YM, Tian CF, et al. Diversity and biogeography of rhizobia isolated from root nodules of Glycine max grown in Hebei Province, China. Microb Ecol. 2011;61:917–931. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9820-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Appunu C, N'Zoue A, Laguerre G. Genetic diversity of native Bradyrhizobia isolated from soybeans (Glycine max L.) in different agricultural-ecological-climatic regions of India. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5991–5996. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01320-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Appunu C, Sasirekha N, Prabavathy VR, Nair S. A significant proportion of indigenous rhizobia from India associated with soybean (Glycine max L.) distinctly belong to Bradyrhizobium and Ensifer genera. Biol Fertil Soils. 2009;46:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Han LL, Wang ET, Han TX, Liu J, Sui WH, et al. Unique community structure and biogeography of soybean rhizobia in the saline-alkaline soils of Xinjiang, China. Plant and. 2009;324:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hungria M, Chueire Lígia Maria de O, Coca RG, Megías M. Preliminary characterization of fast growing rhizobial strains isolated from soyabean nodules in Brazil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2001;33:1349–1361. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00040-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bauer AW, Kirby WMM, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am Jounal Clin Pathol. 1966;36:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ormeño-Orrillo E, Martínez-Romero E. Phenotypic tests in Rhizobium species description: an opinion and (a sympatric speciation) hypothesis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. Past and future species definitions for bacteria and archaea. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015;38:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yates R, Howieson J, Hungria M, Bala A, O’Hara G, et al. Authentication of rhizobia and assessment of the legume symbiosis in controlled plant growth systems. In: Howieson J, Dilworth M, editors. Working with Rhizobia. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR); 2016. pp. 73–108. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lasse Grönemeyer J, Hurek T, Reinhold-Hurek B. Bradyrhizobium kavangense sp. nov., a symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium from root nodules of traditional Namibian pulses. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4886–4894. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.