Abstract

Objective

To identify ethnic differences in proportion positive for SARS-CoV-2, and proportion hospitalised, proportion admitted to intensive care and proportion died in hospital with COVID-19 during the first epidemic wave in Wales.

Design

Descriptive analysis of 76 503 SARS-CoV-2 tests carried out in Wales to 31 May 2020. Cohort study of 4046 individuals hospitalised with confirmed COVID-19 between 1 March and 31 May. In both analyses, ethnicity was assigned using a name-based classifier.

Setting

Wales (UK).

Primary and secondary outcomes

Admission to an intensive care unit following hospitalisation with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. Death within 28 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test.

Results

Using a name-based ethnicity classifier, we found a higher proportion of black, Asian and ethnic minority people tested for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR tested positive, compared with those classified as white. Hospitalised black, Asian and minority ethnic cases were younger (median age 53 compared with 76 years; p<0.01) and more likely to be admitted to intensive care. Bangladeshi (adjusted OR (aOR): 9.80, 95% CI 1.21 to 79.40) and ‘white – other than British or Irish’ (aOR: 1.99, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.44) ethnic groups were most likely to be admitted to intensive care unit. In Wales, older age (aOR for over 70 years: 10.29, 95% CI 6.78 to 15.64) and male gender (aOR: 1.38, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.59), but not ethnicity, were associated with death in hospitalised patients.

Conclusions

This study adds to the growing evidence that ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by COVID-19. During the first COVID-19 epidemic wave in Wales, although ethnic minority populations were less likely to be tested and less likely to be hospitalised, those that did attend hospital were younger and more likely to be admitted to intensive care. Primary, secondary and tertiary COVID-19 prevention should target ethnic minority communities in Wales.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Secondary analysis of data obtained through routine national COVID-19 surveillance.

Studies relying on clinician reported ethnicity contain high proportions of missing and poor quality data.

Using a proven name-based classifier, we were able to assign ethnicity to nearly all participants.

While sensitivity and specificity of the classifier varies in specific ethnic groups and is poor in black British and people of mixed ethnicity, its performance is quantifiable, and classification bias can be taken into account when interpreting findings.

Age, gender and deprivation were taken into account in the analysis, but individual data on history of chronic disease were poorly recorded, and treatment histories once hospitalised were not available.

Introduction

There is growing evidence that black, Asian and other minority ethnic (BAME) people living in Europe are at increased risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and, if infected, are more likely to have severe disease.1 In the UK, the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre first raised concerns that BAME people were over-represented among patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care.2 These findings were reported widely in the media and discussed in opinion pieces.3–7 In Wales, the First Minister established an advisory group to examine the issue and provide recommendations to reduce ethnic inequality in COVID-19 outcomes.8 While focusing on COVID-19, this group has recognised the underlying inequalities BAME people experience in their lives, which are likely to have impacted in ethnic disparities in COVID-19.

Investigating ethnic health inequalities is hampered by the poor recording of ethnicity in clinical data. This is the case for COVID-19 notifications and laboratory reports in Wales. In order to rapidly investigate ethnic variation in COVID-19 epidemiology, we applied Onomap, a name-based ethnicity classification tool developed by the Department of Geography at University College London that has been found effective in 30 other published studies in healthcare, epidemiology and public health.9 This was applied to routinely collected, named COVID-19 laboratory test data, held by Public Health Wales Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre.

Methods

Participants

We obtained routine surveillance data on 77 555 SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests carried out by Public Health Wales and authorised as at 1300 hours, 31 May 2020 from Microbiology Datastore, a repository of test results recorded in the all-Wales Laboratory Information Management System.

Data were also obtained on records of 4046 hospitalised patients (people admitted to hospital within 14 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test or individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 while in hospital) as at 1700 hours, 31 May 2020 available in IC-Net, an infection prevention and control information management system. These data contained information on whether an individual was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU).

These individual person data on hospitalised cases were linked to records of 1309 COVID-19 in-hospital deaths (COVID-19 cases who died in hospital and had a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 28 days or less prior to the date of death or 7 days after death) reported to Public Health Wales’ COVID-19 mortality surveillance scheme to 1700 hours, 31 May, as at 28 June 2020.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity was categorised using the name-based ethnicity classifier, Onomap, a software tool developed by geographers at University College London, and the 2001 Census classification of ethnicity.10 We collapsed the Census categories further into: ‘white British or Irish’, ‘white other’, ‘Asian or British Asian’, ‘black or black British’, ‘other ethnicity’ and ‘unclassified’, with a further aggregation to create a ‘BAME’ field, containing all ethnicities other than ‘white British’, ‘white Irish’ or ‘white other’. Unclassified observations were excluded.

Deprivation

Small (Lower Super Output) areas in Wales were assigned a deprivation score using the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation,11 and areas were ordered into quintiles based on the distribution of these scores, ranging from least to most deprived. Each individual was then assigned to a deprivation quintile based on their Lower Super Output Areas of residence.

Statistical analysis

Proportions of population tested, with 95% CIs, were calculated for white and BAME groups using population data from the most recent Office for National Statistics Labour Force Survey.12 Proportion testing positive with 95% CIs were calculated by dividing number positive by number tested for the same time period. Using logistic regression, we calculated ORs for testing positive for ethnic groups, after adjusting for age, sex and deprivation quintile.

Using the cohort of 4046 hospitalised patients, we carried out a logistic regression to calculate ORs for the outcomes: (A) admitted to intensive care and (B) mortality, with 95% CIs, for ethnic groups, in each case using ‘white British or Irish’ ethnicity as the baseline comparator. Independent variables were gender and age group. Multivariable analyses were then used to calculate ORs for ethnic groups while controlling for gender, age group and local area deprivation. Differences in the distributions of previously reported risk factors for fatal outcomes (age, gender and deprivation medical history)13 14 were investigated further in white and BME groups. The Mann-Whitney two-sample test was used to compare differences in the age distribution of BAME and white deaths. ORs with 95% CIs were calculated to compare proportion male and proportion with underlying health conditions among deceased BAME and white individuals. All analysis was carried out using Stata V.14.15

Validation of Onomap’s performance

The performance of Onomap was assessed using three data sets containing reliable self-reported or healthcare professional-reported ethnicity. These data were: a list of people attending a mosque in Wales who were offered screening for hepatitis C (n=189), a list of tuberculosis patients notified by doctors in Wales (n=3267) and a list of patients attending an infectious disease clinic in Poland (n=3184). Using these data as a ‘gold standard’, sensitivity and specificity were calculated to measure Onomap’s performance in correctly classifying specific ethnicities.

Ethical and privacy considerations

Ethical oversight of the project was provided by Public Health Wales National Health Service (NHS) Trust R&D Division. As this work was carried out as part of the health protection response to a public health emergency in Wales, using routinely collected surveillance data, Public Health Wales R&D Division advised that NHS research ethics approval was not required. The use of named patient data in the investigation of communicable disease outbreaks and surveillance of notifiable disease is permitted under Public Health Wales’ Establishment Order. Data were held and processed under Public Health Wales’ information governance arrangements, in compliance with the Data Protection Act, Caldicott Principles and Public Health Wales guidance on the release of small numbers. No data identifying protected characteristics of an individual were released outside Public Health Wales. Validation work was from a project that had previously received permission from the Confidentiality Advisory Group to process patient data on tests for viral hepatitis carried out by laboratories in Wales, and research ethics approval from West of Scotland REC4 (Application title: Incidence of infectious disease in BAME groups using Onomap; CAG reference: 16/CAG/0133; IRAS project ID: 210327 REC reference: 16/WS/018).

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients or the public were involved in the design and conduct of our research, and the work has been shared with the Welsh Government BAME COVID-19 Advisory group, which contains community and stakeholder groups on a number of occasions. This research has also been presented to the Race Council Cymru.

Funding

No external funding was sought. The study was done with existing Public Health Wales resources.

Results

Ethnicity classification

Onomap estimated the ethnicity of 98.1% (13 789/14 054) of tested individuals, 99.2% (4013/4046) of those hospitalised, 97.4% (305/313) of those admitted to intensive care and 99.6% (1304/1309) of those who died following admission to hospital.

Testing and hospitalisation

By classifying ethnicity using names, we estimate that 3.7% (n=2896) tests were of BAME individuals. Using the most recent Statistics Wales population estimates for ethnic groups in Wales,12 this represents 1580 tests per 100 000 population in BAME, compared with 2512 tests per 100 000 population in white ethnic groups.

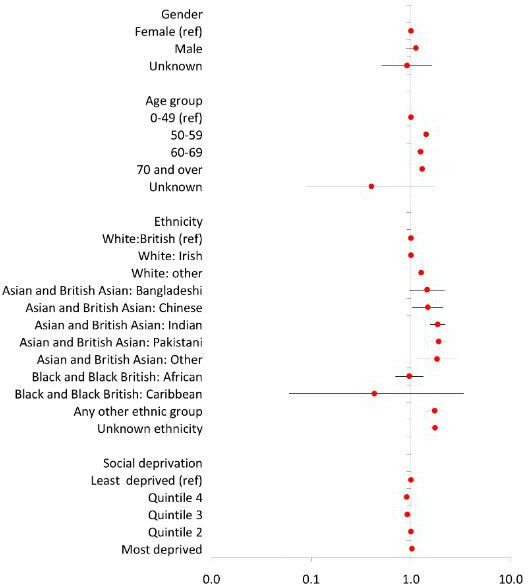

While white groups were more likely to be tested for SARS-CoV-2, BAME groups were more likely to test positive. Of 14 054 people tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Wales on 31 May 2020, Onomap classified 13 092 in white ethnic groups and 697 in BAME groups. Ethnic groups most likely to test positive were: Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Asian – other and White – other (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Determinants of having a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. Adjusted ORs with 95% CIs are given for male gender, compared with female, older age groups compared with those aged less than 50 years, small area deprivation quintile comparing with least deprived, and Onomap estimated ethnicities, compared with ‘white British’. ORs greater than 1 represent an increased risk; ORs less than 1 represent a decreased risk. Ninety-five per cent CIs not crossing 1 reflect that the OR is statistically significant.

Of all those testing positive, a smaller proportion (15.1%) of those tested in the BAME group attended hospital compared with the white group (29.9%: see table 1). However, the trend was reversed in people aged 50–59 years: 23.8% of positive BAME individuals aged 50–59 years attended hospital, compared with 16.3% of white individuals testing positive. The median age of hospitalised BAME individuals was 53 years compared with 76 years for white individuals (p<0.01; Mann-Whitney two-sample test).

Table 1.

Ethnicity breakdown of individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 in Wales and proportions hospitalised, attending intensive care units (ICU) and deceased

| Ethnicity* | Positive tests | Hospitalised | % hospitalised (95% CI) | Attending ICU | % hospitalised attending ICU (95% CI) | Deceased citing COVID-19 | % hospitalised and deceased citing COVID-19 (95% CI) | |||

| All ethnicities | 14 054 | 4046 | 28.8 | (28.0 to 29.5) | 313 | 7.7 | (6.9 to 8.6) | 1309 | 32.4 | (30.9 to 33.8) |

| White British and Irish | 12 565 | 3812 | 30.3 | (29.5 to 31.2) | 262 | 6.9 | (6.1 to 7.7) | 1274 | 33.4 | (31.9 to 34.9) |

| White – other | 527 | 96 | 18.2 | (15.0 to 21.8) | 20 | 20.8 | (13.2 to 30.3) | 19 | 19.8 | (12.4 to 29.2) |

| All white ethnicities | 13 092 | 3908 | 29.9 | (29.1 to30.6) | 282 | 7.2 | (6.4 to8.1) | 1293 | 33.1 | (31.6 to34.6) |

| Asian and British Asian (Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi) | 371 | 62 | 16.7 | (13.1 to 20.9) | 18 | 29.0 | (18.1 to 41.9) | <10 | – | |

| Black and black British | 54 | <10 | – | <10 | – | <10 | – | |||

| Chinese | 40 | <10 | – | <10 | – | <10 | – | |||

| Other | 232 | 30 | 12.9 | (8.9 to 17.9) | <10 | – | <10 | – | ||

| All non-white ethnicities | 697 | 105 | 15.1 | (12.5 to17.9) | 23 | 21.9 | (14.4 to31.0) | 11 | 10.5 | (5.3 to18.0) |

| Unknown | 265 | 12 | 4.5 | (2.4 to 7.7) | <10 | 66.7 | (34.9 to 90.1) | <10 | 41.7 | (15.2 to 72.3) |

*Onomap estimates of ethnicity.

Admission to intensive care

Of those attending hospital, a much higher proportion (21.9%) of BAME individuals were admitted to intensive care compared with white individuals (7.2%). Proportions of hospitalised patients admitted to ICU were highest among the ‘Asian and British Asian – Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi’ (29.0%) and ‘white – other’ (20.8%) groups. The median age of BAME patients admitted to ICU was 51 years compared with 58 years for white individuals (p<0.01; Mann-Whitney two-sample test). Among hospitalised patients aged between 50 and 59 years, 27.6% of BAME patients were admitted to ICU compared with 21% of white patients. More patients died in hospital without being admitted to ICU. Of all those attending hospital, 10.5% of patients identified as BAME died compared with 33.1% of white patients (table 1).

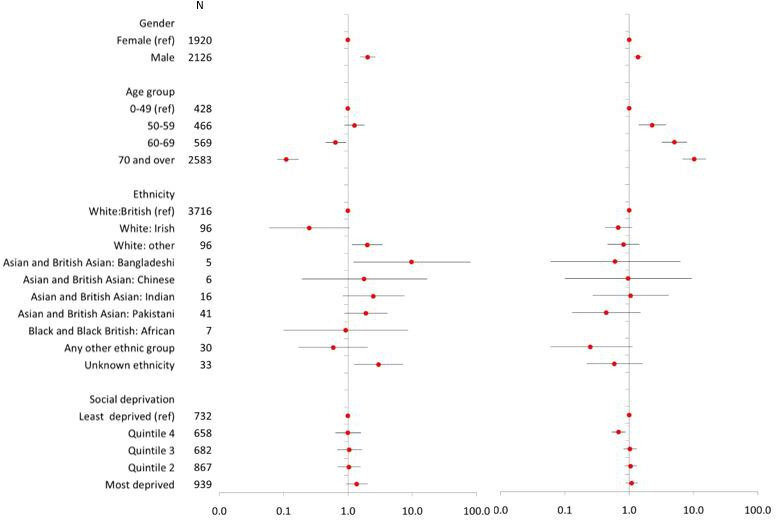

We successfully linked all records of 4046 people hospitalised with COVID-19, those admitted to ICU and those who died in hospital, all as at 31 May 2020, using NHS numbers. Intensive care was more likely in hospitalised males (aOR: 2.03, 95% CI 1.55 to 2.65) and in younger patients (table 2, figure 2). When specific ethnicities were examined, being admitted to ICU was more likely in ‘white other’, ‘Asian and British Asian – Bangladeshi’, ‘Asian and British Asian – Indian’ and ‘Asian and British Asian – Pakistani’ ethnic groups. After adjusting for gender, age and social deprivation, ‘white other’ (aOR: 1.99, 95% CI 1.15 to 3.44) and ‘Bangladeshi’ (aOR: 9.8, 95% CI 1.21 to 79.40), ethnic groups remained significantly more likely to be admitted to ICU.

Table 2.

Personal characteristics associated with severe outcomes for Welsh residents hospitalised with COVID-19 on 31 May 2020

| Personal characteristic | Hospitalised | Received intensive care | Died | ||||||

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 1920 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Male | 2126 | 1.90 | (1.49 to 2.43) | 2.03 | (1.55 to 2.65) | 1.28 | (1.12 to 1.47) | 1.38 | (1.19 to 1.59) |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 0–49 | 428 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| 50–59 | 466 | 1.24 | (0.89 to 1.72) | 1.27 | (0.89 to 1.80) | 2.43 | (1.49 to 3.95) | 2.29 | (1.40 to 3.74) |

| 60–69 | 569 | 0.64 | (0.45 to 0.91) | 0.64 | (0.45 to 0.93) | 5.93 | (3.80 to 9.25) | 5.11 | (3.26 to 8.03) |

| 70 and over | 2583 | 0.11 | (0.07 to 0.15) | 0.11 | (0.08 to 0.17) | 11.40 | (7.55 to 17.20) | 10.29 | (6.78 to 15.64) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White: British | 3716 | – | – | – | – | ||||

| White: Irish | 96 | 0.43 | (0.14 to 1.37) | 0.25 | (0.06 to 1.06) | 0.73 | (0.47 to 1.16) | 0.68 | (0.42 to 1.10) |

| White: other | 96 | 3.51 | (2.11 to 5.84) | 1.99 | (1.15 to 3.44) | 0.49 | (0.29 to 0.81) | 0.82 | (0.46 to 1.44) |

| Asian and British Asian: Bangladeshi | <10 | 8.89 | (1.48 to 53.49) | 9.8 | (1.21 to 79.40) | 0.49 | (0.06 to 4.43) | 0.61 | (0.06 to 6.29) |

| Asian and British Asian: Chinese | <10 | 2.67 | (0.31 to 22.93) | 1.78 | (0.19 to 16.85) | 0.40 | (0.05 to 3.39) | 0.97 | (0.10 to 9.36) |

| Asian and British Asian: Indian | 16 | 6.07 | (2.09 to 17.59) | 2.49 | (0.83 to 7.53) | 0.46 | (0.13 to 1.60) | 1.06 | (0.27 to 4.14) |

| Asian and British Asian: Pakistani | 41 | 4.89 | (2.42 to 9.88) | 1.91 | (0.89 to 4.09) | 0.16 | (0.05 to 0.51) | 0.44 | (0.13 to 1.50) |

| Black and Black British: African | <10 | 2.22 | (0.27 to 18.55) | 0.93 | (0.10 to 8.59) | 0.33 | (0.04 to 2.74) | – | to |

| Any other ethnic group | 30 | 1.54 | (0.46 to 5.12) | 0.59 | (0.17 to 2.01) | 0.15 | (0.03 to 0.62) | 0.25 | (0.06 to 1.12) |

| Unknown ethnicity | 33 | 4.27 | (1.91 to 9.56) | 2.99 | (1.25 to 7.18) | 0.35 | (0.14 to 0.92) | 0.59 | (0.22 to 1.61) |

| Deprivation | |||||||||

| Most deprived | 939 | 1.70 | (1.17 to 2.45) | 1.37 | (0.93 to 2.02) | 0.95 | (0.77 to 1.16) | 1.10 | (0.88 to 1.36) |

| Quintile 2 | 867 | 1.25 | (0.85 to 1.84) | 1.03 | (0.69 to 1.56) | 0.93 | (0.76 to 1.15) | 1.06 | (0.85 to 1.32) |

| Quintile 3 | 682 | 1.08 | (0.71 to 1.64) | 1.05 | (0.68 to 1.65) | 1.01 | (0.81 to 1.26) | 1.03 | (0.82 to 1.30) |

| Quintile 4 | 658 | 1.09 | (0.72 to 1.67) | 1.00 | (0.64 to 1.58) | 0.68 | (0.54 to 0.86) | 0.69 | (0.54 to 0.87) |

| Least deprived | 732 | – | – | – | – | ||||

Figure 2.

Determinants of: (1) being admitted to intensive care unit (ICU); and (2) in-hospital mortality in 4046 individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 in Wales on 31 May 2020, as at 28 June 2020. Adjusted ORs (aORs) with 95% CIs are given for male gender, compared with female, older age groups compared with those aged less than 50 years, small area deprivation quintile comparing with least deprived and Onomap estimated ethnicities, compared with ‘white British’. ORs greater than 1 represent an increased risk; ORs less than 1 represent a decreased risk. Ninety-five per cent CIs not crossing 1 reflect that the OR is statistically significant.

Hospitalised cases living in the most deprived areas of Wales were significantly more likely to attend ICU (OR: 1.70; 95% CI 1.17 to 2.45). However, this effect did not remain significant after adjusting for age, sex and ethnicity (aOR: 1.37, 95% CI 0.93 to 2.02).

Mortality

Likelihood of dying was significantly higher for hospitalised males. This effect remained after adjusting for age and ethnicity (aOR: 1.38, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.59) (table 2, figure 2). No increase was observed in risk of death with increasing deprivation. There was a strong association between increasing age and death from COVID-19, which remained after adjusting for gender, ethnicity and social deprivation (aOR for aged 70 years and over: 10.29 (95% CI 6.78 to 15.64). However, there was no evidence from this study that BAME groups were more likely to die from COVID-19 than white British or Irish groups, even after adjusting for gender, age and social deprivation (table 2).

To investigate further, we compared the differences in the distribution of previously reported risk factors for fatal outcome13 in white and BAME groups who had died. BAME people who died in Wales with COVID-19 were younger than white people who died (BAME median age 71 years compared with 79 years for white people; p=0.06, Mann-Whitney two-sample test). Underlying chronic disease was recorded for 50% of deaths. There was a higher proportion of BAME people (72.7 (95% CI 39.0 to 94.0)) that had a history of underlying chronic disease compared with white people (49.6 (95% CI 46.8 to 52.3)).

Validation of Onomap

Onomap returned predicted ethnicity for 97% of the 6640 names in the four data sets. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated for each ethnic group. Onomap generally had a high specificity, that is: it was unlikely to return a false ethnicity in people self-reporting a given ethnicity (table 3). Specificity was 77% for white ethnicities, indicating that a proportion of people in BAME groups will be misclassified as white. In terms of its sensitivity, that is its likelihood of detecting all people self-reporting as an ethnic group, Onomap was poor for some ethnic groups, most notably for those self-reporting as black or British black. In other words, many people self-reporting as black or black British will be misclassified, most likely as white.

Table 3.

Validation of Onomap

| Ethnicity | Ethnicity reported by participant | Ethnicity predicted by Onomap | Ethnicity correctly predicted | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| White British or Irish | 1681 | 1811 | |||

| Other white | 3235 | 3418 | |||

| Total white | 4916 | 5229 | 4844 | 98.5% | 77.7% |

| Indian | 364 | 239 | |||

| Pakistani | 313 | 348 | |||

| Bangladeshi | 96 | 88 | |||

| Chinese | 55 | 18 | |||

| Other Asian | <10 | 118 | |||

| Total Asian or Asian British | 837 | 811 | 609 | 72.8% | 96.5% |

| Black – African | 344 | 142 | |||

| Black – Caribbean | 10 | <10 | |||

| Other black | 23 | <10 | |||

| Total black or black British | 377 | 143 | 112 | 29.7% | 99.5% |

| Arabic | 39 | 279 | |||

| Other | <10 | <10 | |||

| Other ethnic group | 45 | 283 | 24 | 53.3% | 96.1% |

| Mixed | 234 | <10 | – | ||

| Unclassified/unknown | 231 | 174 | <10 | 3.5% | 97.4% |

| Total | 6640 | 6640 | 5589 | 87.4% | 96.1% |

Estimated sensitivity and specificity of Onomap by ethnic group. Calculated by measuring the performance of Onomap to predict ethnicity in three clinical data sets* already containing self-reported or healthcare professional-reported ethnicity.

*Three data sets that included self-reported or healthcare professional-reported ethnicity were used to validate Onomap: a list of individuals attending a mosque in Wales who were offered screening for hepatitis C (n=189), a list of tuberculosis patients notified by doctors in Wales (n=3267) and a list of patients attending an infectious disease clinic in Poland (n=3184).

Discussion

This was a rapid analysis of routinely available national surveillance data using name-based ethnicity classification software, carried out in response to the emerging epidemic in Wales. It adds to the evidence of increased risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes in ethnic minorities in Western Europe and the USA.

BAME people living in Wales were less likely to be tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the first COVID-19 wave, but of those tested, people in Chinese, Indian, Pakistani and white – other groups were more likely to test positive. It should be noted that testing in the first wave was mainly of people hospitalised and those working in health and social care, so trends in testing and in proportion positive need to be interpreted with caution.

We found risk of severe COVID-19, indicated by admission to ICU, to be higher in many ethnic minorities living in Wales and significantly higher in those of Bangladeshi ethnicity and in white ethnic groups, other than British or Irish. Bangladeshi communities have been identified in other studies as being at particular risk of the effects of COVID-19.16 The second group we identified, ‘white – other’, will contain a range of nationalities, but in Wales, recent migrants from Eastern Europe will comprise a significant proportion. The risk associated with the latter group has not been previously reported and is an important finding given recent outbreaks reported in factory settings in Wales where many European migrants are employed. That the white – other group is at increased risk of severe COVID-19 gives weight to the hypothesis that ethnic disparities are socioeconomic in basis.

The finding that certain minority ethnic groups are at higher risk of being admitted to intensive care but are no more likely to die than the white British and Irish group was also found in the CO-CIN cohort study involving 23 577 patients with COVID-19 attending hospitals in the UK.16 This slightly counterintuitive finding may be a genuine finding or may be the result of classification bias.

First, if genuine, differences in the age distribution of cases in white and BAME groups are likely to be a factor. During early 2020, COVID-19 mortality was observed overwhelmingly in the elderly, with white men over 70 years disproportionally affected. These patients may have been less likely to have been admitted to ICU for treatment. BAME populations in Wales are generally younger,16 and lower median ages were observed in hospitalised BAME individuals. The finding that despite being generally younger, BAME individuals were more likely to be admitted to ICU is an important finding.

The lack of increased risk of mortality is at odds with some studies from England that have found that COVID-19 deaths have been disproportionally high in BAME groups. Of course, it is always possible that Wales, with a more deprived general population relative to England, a lower density of BAME people and smaller urban conurbations, presents a less unequal risk setting. However, there may be methodological issues affecting this finding. It is likely that Onomap underestimates the absolute number of BAME individuals, particularly for black groups. The misclassification of black as white may have led to an under estimation of relative risk. It is also possible that date of onset to death is longer in younger people and that our study did not take sufficient account of this.

The absence of individual-level data on comorbidities is a limitation of this study. Further work is currently being carried out using linkage of COVID-19 notification data with other routine health records to further understand risks associated with hospitalisation. Also, we only had access to deaths that occurred in hospital. It is possible that there may have been ethnic differences in the proportion of people dying outside of hospital.

Onomap has been used widely as a tool in public health, for example, in studies investigating variation in influenza mortality,17 hepatitis B infection18 and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination uptake.19 However, Onomap has limitations, and all findings should be interpreted in light of these. We previously validated the tool using data containing self-reported or healthcare professional-reported ethnicity. Onomap performs well for most ethnicities but has a low sensitivity for black or black British individuals. Risks identified for black and black British groups are therefore likely to be underestimated. Kandt and Longley20 have published a comparison of Onomap with self-reported ethnicity in the 2011 Census. Notwithstanding apparent success in 30 reported studies in public health, healthcare and epidemiology (and wider application in equity audits in, inter alia, housing allocation, management science and social media), the reliability and limitations of such methods should be acknowledged and understood. In the absence of good ethnicity recording in routine health records, it does facilitate scientific investigation with margins of error that are understood. Moreover, many of the existing studies where individual person ethnicity is available have missing data and are not without their own classification bias. Anecdotally, members of minority ethnic groups are more likely to defer from reporting their ethnicities, and clinician-based classification is understood to be unreliable.

One of the recommendations of the Welsh Government Advisory Group is to improve recording of ethnicity in routine health data, and a data improvement plan is urgently required so ethnicity can be included in routine public health surveillance. There is an urgent need for all European countries carrying out COVID-19 surveillance to report trends by ethnicity, in order to inform local infection prevention and control policy and practice. Ethnic variation should also be considered in the design of interventions and in crisis communication.

Wales is less ethnically diverse than many other areas of the UK, but its BAME population has increased in recent years. In 2001, the Census recorded 2.1% of the population as BAME. This increased to 4.4% in the 2011 Census. Most recent estimates from the Labour Force Survey indicates that this has grown to 5.5%.12 The Welsh Government has established an advisory group to investigate issues around COVID-19 in BAME groups and has published a series of recommendations. In Wales, an occupational risk assessment tool has been developed with the aim of reducing risk of infection in those most vulnerable to severe infection.21 This tool, developed initially for the healthcare sector, is for all ethnicities but includes a weighting to account for the emerging evidence of increased risk in BAME individuals. A recent report by the Race Disparity Unit in England22 provides a summary of the actions being undertaken in England to reduce ethnic variation in COVID-19, including community engagement initiatives, economic support for work sectors that over-represent minority ethnic groups and asymptomatic testing pilots. Comparing first and early second wave data, early analysis provides evidence that disparities appear to have improved for some ethnic groups including black Africans, black Caribbean, Chinese and Indians but have worsened for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.23 24 In England, as a result of the findings from the QCOVID risk model,14 the list of people shielding has been updated, using a new predictive risk model that combines factors including ethnicity and the postcode where people live and its link with deprivation.

COVID-19 is now a vaccine preventable disease, and vaccination is being rolled out across the UK. There are concerns that vaccination uptake may be lowest in areas with high numbers of minority ethnic populations. Office for National Statistics reports that from early December 2020 to early January 2021, less than half (49%) of black or black British adults reported that they were likely to have the vaccine.25 The latest OpenSAFELY data report that approximately 60% of black people over 70 years have been vaccinated compared with 75% for South Asians and 90% of white people.26 Initiatives are being undertaken to improve vaccine uptake in ethnic minority groups in Wales, and latest data indicate that progress is being made in reducing variation.27

This is a complex topic, and it is still unclear whether ethnic variation in poor outcomes is the result of higher incidence of infection or greater severity of disease. Minority ethnic groups are more likely to live in urban areas, to have public facing jobs, are more likely to live in crowded housing and live in multigenerational households.28 Further research is needed to quantify risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of severe outcomes in ethnic minority communities and better understand the underlying processes behind any disparities. However, there is now enough evidence to act, and effort should be focused on continuing to design innovative interventions for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of COVID-19 in minority ethnic groups.29

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Onomap was purchased from Publicprofiler Ltd. The authors acknowledge the many laboratory and surveillance staff in Public Health Wales involved in developing and maintaining routine COVID-19 surveillance in Wales. Victoria McClure assisted with extracting data from IC-Net.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DanielRhysThom1

Contributors: DRT designed the study, contributed to the analysis and wrote the manuscript. OO contributed to the analysis and commented on the manuscript. AP, GK, MRE, JJ and RS commented on the manuscript and contributed to the validation work. PL commented on the methodology, referee comments and results, including use of the names classification tool. CW and AGS commented on the design and analysis and manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Paul Longley is Director of Publicprofiler Ltd.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Individual data not available but aggregated data may be made available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Pan D, Sze S, Minhas JS, et al. The impact of ethnicity on clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2020;23, :100404. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICNARC – reports, 2020. Available: https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 3.Guardian . Ethnic minorities dying of Covid-19 at higher rate, analysis shows, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cifuentes R. All in it together? the impact of coronavirus on BamE people in Wales. Bevan Foundation, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pareek M, Bangash MN, Pareek N, et al. Ethnicity and COVID-19: an urgent public health research priority. Lancet 2020;395:1421–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30922-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.BMA . Press Release, “Review into COVID-19 impact on BAME communities must be backed by real-time data and include measures to address problem now, says BMA, 2020. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/bma-media-centre/review-into-covid-19-impact-on-bame-communities-must-be-backed-by-real-time-data-and-include-measures-to-address-problem-now-says-bma [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 7.NHS Confederation . The impact of COVID-19 on BME communities and health and care staff, 2020. Available: https://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/2020/04/the-impact-of-covid19-on-bme-communities-and-staff [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 8.Welsh Government . Wales BamE Covid-19 health Advisory group takes a cross-Government approach, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Public Profiler, 2020. Available: https://www.publicprofiler.org/ [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 10.Office for National Statistics . Ethnic group statistics: a guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data. Office for National Statistics, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.StatsWales . Welsh index of multiple deprivation. Available: https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Community-Safety-and-Social-Inclusion/Welsh-Index-of-Multiple-Deprivation [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 12.StatsWales . Ethnicity by area and ethnic group. Available: https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Equality-and-Diversity/Ethnicity/ethnicity-by-area-ethnicgroup [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 13.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584:430–6. 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clift AK, Coupland CAC, Keogh RH, et al. Living risk prediction algorithm (QCOVID) for risk of hospital admission and mortality from coronavirus 19 in adults: national derivation and validation cohort study. BMJ 2020;371:m3731. 10.1136/bmj.m3731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.StataCorp LLC . Stata 14. Available: https://www.stata.com/stata14/ [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 16.Harrison E, Docherty A, Semple C. CO-CIN: Investigating associations between ethnicity and outcome from COVID-19 - report to SAGE, 25 April 2020 - GOV.UK, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/co-cin-investigating-associations-between-ethnicity-and-outcome-from-covid-19-report-to-sage-25-april-2020 [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 17.Zhao H, Harris RJ, Ellis J, et al. Ethnicity, deprivation and mortality due to 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) in England during the 2009/2010 pandemic and the first post-pandemic season. Epidemiol Infect 2015;143:3375–83. 10.1017/S0950268815000576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binka M, Butt ZA, Wong S, et al. Differing profiles of people diagnosed with acute and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in British Columbia, Canada. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:1216–27. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i11.1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollock KG, Tait B, Tait J, et al. Evidence of decreased HPV vaccine acceptance in Polish communities within Scotland. Vaccine 2019;37:690–2. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandt J, Longley PA. Ethnicity estimation using family naming practices. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201774. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welsh Government . COVID-19 workforce risk assessment tool | GOV.WALES, 2020. Available: https://gov.wales/covid-19-workforce-risk-assessment-tool [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 22.Race Disparity Unit . Second quarterly report on progress to address COVID-19 health inequalities- GOV.UK, 2021. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/second-quarterly-report-on-progress-to-address-covid-19-health-inequalities [Accessed 28 Mar 2021].

- 23.Nafilyan V, Islam N, Mathur R. Ethnic differences in COVID-19 mortality during the first two waves of the coronavirus pandemic: a nationwide cohort study of 29 million adults in England. medRxiv 2021. 10.1101/2021.02.03.21251004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhaskaran K, Mathur R, Rentsch CT. Short report: ethnicity and COVID-19 death in the early part of the COVID-19 second wave in England: an analysis of OpenSAFELY data from 1st September to 9th November 2020. medRxiv 2021. 10.1101/2021.02.02.21250989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office for National Statistics . Coronavirus and the social impacts on great Britain: 29 January 2021, 2021. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/29january2021#attitudes-to-covid-19-vaccination-by-different-sub-groups-of-the-population [Accessed 30 Jan 2021].

- 26.OPENSAFELY . “NHS COVID-19 vaccine coverage report,” [online]. Available: https://opensafely.org/research/2021/covid-vaccine-coverage/#weekly-report [Accessed 15 Feb 2021].

- 27.Public Health Wales . Rapid COVID-19 surveillance dashboard” [online]. Available: https://public.tableau.com/profile/public.health.wales.health.protection#!/vizhome/RapidCOVID-19virology-Public/Headlinesummary [Accessed 28 Mar 2021].

- 28.Office for National Statistics . 2011 census general report - Office for national statistics, 2011. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census/howourcensusworks/howdidwedoin2011/2011censusgeneralreport [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 29.Haque Z, Becares L, Treloar N. A Runnymede trust and ICM survey Over-Exposed and Under-Protected the devastating impact of COVID-19 on black and minority ethnic communities in Great Britain Runnymede: intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Individual data not available but aggregated data may be made available.