Abstract

Several biologic agents have been approved for use in dermatology and other disciplines of medicine. However, based on the mechanism of action and a track record of the response, these agents are being increasingly used for off-label purposes to garner control of more remote and difficult disease processes. Herein, we present three difficult to treat patients where innovative uses of biologics beyond their approved indications have yielded good responses. Our first patient was a case of bullous pemphigoid, who showed excellent response to omalizumab. The second case was a patient of lepromatous leprosy with tenosynovitis and erythema nodosum leprosum, who was treated effectively with infliximab. Our third case was a treatment-resistant pyoderma gangrenosum, where infliximab showed a very good response. In the present study, we report the cases to highlight the usefulness of biologics that can expand much beyond the routine FDA approved indications.

Key Words: Biologics, bullous pemphigoid, infliximab, leprosy, off-label use, omalizumab, pyoderma gangrenosum

Introduction

Several biologic agents have been approved for use in dermatology and other disciplines of medicine. In dermatology, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF alpha) Inhibitors such as adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab are approved for the treatment of refractory psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biologic agents targeting IL23 and IL17 also have received approval for the treatment of psoriasis.[1] Rituximab is a chimeric murine-human monoclonal antibody (IgG1 k) directed against CD20 that induces the depletion of B cells. Rituximab has recently, received the US FDA approval for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris.[2] Omalizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the constant region of the immunoglobulin E (IgE) molecule, is highly recommended for the refractory urticarial cases.[3] However, based on the mechanism of action and a track record of the response, these agents are being increasingly used for off-label purposes to garner control of more remote and difficult disease processes. In this case series, we are reporting some innovative use of biologics, in refractory or difficult-to-treat skin diseases.

Case 1

A 65-year-old lady presented with generalized tense blisters over the abdomen, back, chest, and arms which were progressive over the last 6 months. The blisters appeared on an erythematous base with clear fluid, pruritic, and healed with crusting and hyperpigmentation. On examination, Nikolsky sign and bullae spread signs were negative and no mucosal involvement was noted [Figure 1]. On admission, she was diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid as histopathological examination showed split in basal membrane zone (BMZ) with intact epidermis and mixed infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophil. Direct immunofluorescence showed a linear BMZ deposition of IgG.

Figure 1.

Blisters appeared on erythematous, pruritic lesions, and healed with crusting and hyperpigmentation

The patient was already on prednisone 60 mg once daily for 3 months and mycophenolate mofetil was added at the dose of 500 mg twice daily for 4 weeks. Partial remission was achieved after 4 weeks of combination therapy. She was still complaining of intense itching and the appearance of new lesions was noted. During follow-up, she developed steroid-induced diabetes mellitus with fasting blood sugar of 144 mg/dL and postprandial blood sugar of 256 mg/dL. On further investigation, the IgE level (786 IU/mL) was found high. Hence, the decision was taken to start omalizumab and steroid was tapered off over 6 weeks to the dose of 10 mg once daily.

She was started with omalizumab 300 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks. A remarkable improvement was noted, and lesions started disappearing within 2 weeks along with the almost complete resolution of pruritus. Currently, she is on monthly omalizumab with complete resolution of symptoms after 3 months of follow-up [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Improvement of lesions after three months of omalizumab and steroid therapy

Case 2

A 32-year-old male patient was diagnosed as a case of lepromatous leprosy and was on multidrug therapy (MDT) for the last 1 year. He presented to us with complaints of joint pain, swelling, and stiffness of both wrist and ankle joints for the last 2 weeks. On examination thickening and tenderness of the tendons were noted and there was no evidence of joint deformity [Figure 3]. However, he gave a history of recurrent crops of the tender nodular lesion during and after MDT. Magnetic resonance imaging of the right ankle joint was done for evaluation of tenosynovitis which showed small focal peritendinous fluid collection along the flexor digitorium longus tendon along with minimal fluid collection around the ankle joint. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was done from the affected nerve and cytology revealed the presence of foamy macrophages and acid-fast bacilli. PCR from the isolates confirmed the presence of Mycobacterium leprae. A diagnosis of leprosy presenting with tenosynovitis and erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) was made and standard WHO MDT treatment for leprosy was started. Earlier, some of the authors have shown similar presentations of leprosy and with similar proven technologies.[4,5,6] Though he was given a repeated dose of steroids for a short duration, with which tender nodules subsided, tenosynovitis kept on progressing. The patient was given combination therapy of thalidomide 200 mg per day plus prednisone 50 mg per day and MDT was restarted. However, no response was seen after 6 weeks of treatment and he complained of intense pain. We started with infliximab after doing a pre-biologic workup including chest X-Ray and viral serologies. Infliximab was given at a dose of 250 mg diluted in normal saline with dosing schedule at baseline and weeks 2 and 6. The treatment was well-tolerated and good improvement in symptoms was noted. The patient was followed up for 6 months, no recurrence of ENL was seen.

Figure 3.

Thickening and tenderness of the tendons without evidence of joint deformity

Case 3

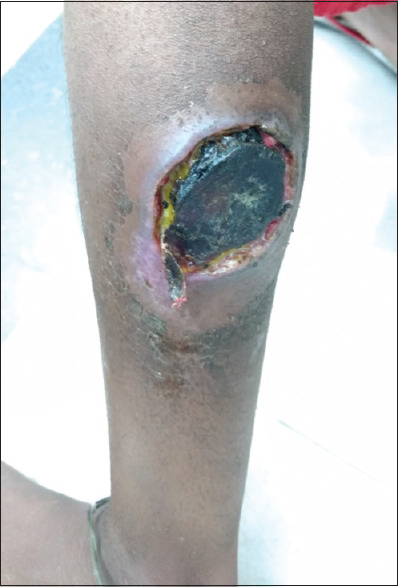

A 26-years old female presented with complaints of a non-healing ulcer on the left leg for 20 days. The ulcer had started with a single pustule but later progressed into a non-healing ulcer at the present site. It was rapidly progressing and intensely painful. Initially, it was serous sticky yellowish but gradually developed a necrotic base with a peripheral rim of erythema and induration surrounding the lesion [Figure 4]. Biopsy showed features of vasculitis with the presence of lymphocytes and neutrophil. A diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) was made. Routine blood investigations were within normal limits. She was initially treated with oral corticosteroid and cyclosporine without any clinical improvement. The patient was admitted and decided to start with infliximab. The pre-biologic workup was within normal limits. Infliximab was given at a dose of 250 mg at baseline and then at weeks 2 and 6 with a presumptive diagnosis of PG. The improvement of the lesion was noted after 2 weeks of therapy. Marked improvement of both ulcers and pain was seen after 6 weeks of treatment and no recurrence of new lesions was seen [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Nonhealing ulcer with necrotic base and peripheral rim of erythema and induration surrounding the lesion

Figure 5.

Improvement of the lesion after 6 weeks of infliximab therapy

Discussion

Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to human IgE. It inhibits the binding of IgE to the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) on mast cells and basophils thus, limiting the release of mediators of the allergic response.[7] Over the recent years studies HAVE shown the role of IgE in the pathogenesis of Bullous pemphigoid (BP).[8] Thus, inhibition of IgE/IgE receptor interaction can become a positive option for the therapy of BP. In our first case, the patient was suffering from BP as evident by histopathological examination.

Our patient was initially treated with systemic steroid and subsequently, Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) was added without significant improvement of the lesion. Moreover, she developed an adverse effect due to long-term steroid use. There was some recent report suggesting the role of Omalizumab in BP. Therefore, we decided to taper steroids and started her on omalizumab as her IgE level was also very high. The lesions disappeared and her blood sugar level became normal. The drug was well-tolerated with no signs of adverse effects. Omalizumab can be successfully used in those patients for whom the disease is refractory to systemic steroids and other immunosuppressive medications. The mechanism of action of omalizumab in patients with BP is not completely understood. But the rationality is based on high IgE level and patients with BP express IgE autoantibodies against BP antigens thereby downgrading the IgE expression that can help in the treatment of BP. There are few case reports published in the last 5 years, demonstrating the efficacy of omalizumab in BP. Although a large clinical trial needs to be performed to come to any conclusion, it seems more prudent to use omalizumab in patients with recalcitrant BP have elevated IgE level.

Infliximab is an IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes both soluble and membrane-bound TNF-α without involving TNF-β. Infliximab blocks the binding of TNF-α to its receptor, attaches complement and produces antibody-mediated cytotoxicity resulting in lysis of cells expressing membrane-bound TNF-α.[9]

In our second case report, the patient was suffering from Hansen's disease, also known as leprosy, which is a chronic infectious skin disease that affects the peripheral nerve skin, upper respiratory tract, eyes, and nasal mucosa. The disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae can affect all age groups. Earlier it was shown by some of the authors that leprosy could present as isolated tenosynovitis with the help of FNAC and DNA PCR. Delayed treatment and prolonged recurrence of the disease can lead to complications such as claw-like hands, disfiguration of face, blindness, muscle weakness, etc. Our patient was on MDT and steroids but recurrence of new lesions with joint pain and tenosynovitis did not resolve. We added thalidomide but could not control the symptoms. However, the symptoms were increasing even under control only after using infliximab at a dose of 3 to 5 mg/kg at baseline and on weeks 2 and 6 followed by every 8 weeks thereafter. The rapid response was seen noted after the second week of treatment. Earlier there was a single case report of ENL being effectively treated with infliximab. In another case report, ENL was treated with etanercept, another TNF alpha inhibitor. Hence, infliximab can be considered as a treatment option for type 2 resistant cases of lepra reaction.

In our third case report, the patient suffered from PG, which is an immune-mediated chronic ulcerating skin condition. The disease is characterized by deep skin ulcers with undermining edges mostly in the lower limbs. The cause of PG is unknown but mostly seen in association with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. We started with conventional treatment with oral corticosteroid and cyclosporine but not much improvement was noticed. The disease went on aggravating and the patient complained of pain and discomfort. We started with infliximab at the dose of 250 mg of IV infusion at 0. 2 and 6 weeks. We observed a rapid and significant clinical response within 2 weeks of treatment. The drug was well-tolerated with no signs of adverse effects. In a randomized double-blinded controlled trial infliximab at a dose of 5 mg/kg was noted to be superior to placebo in the treatment of PG.[10] In our case, marked improvement was noted only after treatment with infliximab. Infliximab can be considered as a treatment of choice in the refractory cases of PG.

Our study presents three difficult-to-treat cases, where biologics was proved to be helpful. We report the cases to highlight the usefulness of biologics and that they can expand much beyond the routine Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved indications.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Boutet MA, Nerviani A, Gallo Afflitto G, Pitzalis C. Role of the IL-23/IL-17 axis in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: The clinical importance of its divergence in skin and joints. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19020530. pii: E530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murrell DF, Peña S, Joly P, Marinovic B, Hashimoto T, Diaz LA, et al. Diagnosis and management of pemphigus: Recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:575–585.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neema S, Chatterjee M. Omalizumab for management of refractory urticaria: Experience of a tertiary care centre in Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:66–9. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_342_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De A, Surana TV, Biswas S, Reja AH, Chatterjee G. Isolated tenosynovitis as a sole manifestation: The great mimicker still continues to surprise us. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:213. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reja AH, De A, Biswas S, Chattopadhyay A, Chatterjee G, Bhattacharya B, et al. Use of fine needle aspirate from peripheral nerves of pure-neural leprosy for cytology and PCR to confirm the diagnosis: A pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:789–94. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.120731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De A, Hasanoor Reja AH, Aggarwal I, Sen S, Sil A, Bhattacharya B, et al. Use of fine needle aspirate from peripheral nerves of pure-neural leprosy for cytology and polymerase chain reaction to confirm the diagnosis: A follow-up study of 4 years. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:635–43. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_115_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurer M, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ, Saini S, Grattan C, Gimenéz-Arnau A, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:924–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cozzani E, Gasparini G, Di Zenzo G, Parodi A. Immunoglobulin E and bullous pemphigoid. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28:440–8. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2018.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalliolias GD, Ivashkiv LB. TNF biology, pathogenic mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, Bowden JJ, Williams JD, Griffiths CE, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]