Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of short birth interval (SBI) on neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality in Ethiopia.

Design

A nationally representative cross-sectional survey.

Setting

This study used data from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016.

Participants

A total of 8448 women who had at least two live births during the 5 years preceding the survey were included in the analysis.

Outcome measures

Neonatal mortality (death of the child within 28 days of birth), infant mortality (death between birth and 11 months) and under-five mortality (death between birth and 59 months) were the outcome variables.

Methods

Weighted logistic regression analysis based on inverse probability of treatment weights was used to estimate exposure effects adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

The adjusted ORs (AORs) of neonatal mortality were about 85% higher among women with SBI (AOR=1.85, 95% CI=1.19 to 2.89) than those without. The odds of infant mortality were twofold higher (AOR=2.16, 95% CI=1.49 to 3.11) among women with SBI. The odds of under-five child mortality were also about two times (AOR=2.26, 95% CI=1.60 to 3.17) higher among women with SBI.

Conclusion

SBI has a significant effect on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia. Interventions targeting SBI are warranted to reduce neonatal, infant and under-five mortality.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology, maternal medicine, community child health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The application of inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) mimics a randomised controlled trial by matching two comparison groups using a conditional probability of receiving exposure (short birth interval in this case) given a set of covariates.

The study has also additional strengths, such as using data from a nationally representative survey with a large sample size.

The application of direct acyclic graphs, a graphical tool used to identify minimum adjustment sets, which defined the set of explanatory variables for the propensity scores model was another strength of this study.

Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, temporal associations between short birth interval and neonatal, infant and under-five mortality may not be established.

Another limitation of our study could be associated with the non-randomised design of the study. Although a propensity score-based analysis, IPTW, was used in our study, it may not account for unknown confounders in the same way that a randomised trial can, so the effect of residual confounders may not be avoided.

Introduction

Short birth interval (SBI), defined as a birth-to-birth interval of less than 33 months,1 is a key public health problem with an estimated prevalence of 45.8% in Ethiopia.2 Previous studies2–4 have revealed the multifactorial nature of SBI, its spatial variation and socioeconomic inequality in Ethiopia. Only about one-third of women in Ethiopia use modern contraceptives, which can prevent SBI.5 Literature has also shown the effects of SBI may include, but are not limited to, preterm birth,6 7 low birth weight,6 7 small sizes for gestational age,6 congenital anomalies,8 9 autism,10 miscarriage, pre-eclampsia and premature rupture of membranes.11 12

Neonatal, infant and under-five mortality are defined as the death of a child within 28 days of birth, before the age of 1 year, and before 5 years, respectively.5 These mortality outcomes are regarded as a highly sensitive (proxy) measure of population health, a country’s poverty and socioeconomic development status, and the availability and quality of health services and medical technology.13 14

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.2 states that all countries should aim to reduce the neonatal mortality rate to 12 deaths per 1000 live births or fewer, and reduce under-five mortality to 25 deaths per 1000 live births or fewer, by 2030.15 The Growth and Transformation Plan of Ethiopia (GTPE) II also targets reductions in neonatal, infant and under-five mortality rates, from 28 per 1000 live births, 44 per 1000 live births and 64 per 1000 live births in 2014/2015 to 10, 20 and 30 per 1000 live births by 2019/2020, respectively.16 However, the 2019 Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey report revealed that the neonatal, infant and under-five mortality rates in Ethiopia were 30, 43 and 55 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively: still much higher than GTPE targets.16 17

Literature from Ethiopia has shown that neonatal, infant and under-five mortality are associated with maternal education,18 19 lack of antenatal care,20 home delivery,21 preterm birth,20 22 low birth weight,21 22 multiple births,18 20 23 24 sex of the child,18 20 23–26 wealth status,27 28 place of residence,21 24 25 sources of drinking water,28 and lack of access to an improved toilet facility.29

Although previous studies18–20 24 25 28–32 have suggested birth interval as one factor influencing neonatal, infant, under-five mortality, these studies have several limitations. Of the key limitations is that these studies18–20 24 25 28–32 did not use the WHO recommended1 definition of SBI. Understanding the impact of SBI on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality, using the WHO definition,1 is necessary for the formulation of valid, consistent policies and health planning strategies and interventions to improve child health outcomes. Second, women who were not eligible to provide birth interval information (ie, those who had given birth only once) were included in the analysis of some studies.20 25 29 This may result in underestimation or obscuration of the true effect of birth interval on child mortality. Third, even among studies using the same definition of SBI, findings have been inconsistent.20 25 One of the studies using national data20 did not control for a range of potential confounders including maternal education, wealth status, number of children and region of residence, even though these data were available in the datasets used for analysis. Similarly, another previous study30 that used national data did not condition on maternal occupation, husband education, husband occupation, the total number of preceding children, regions, access to mass media and women’s decision-making autonomy. In addition, various studies did not consider SBI as a potential predictor of neonatal,22 26 27 33–36 infant,19 37 38 and under-five mortality39–42 in their analysis.

Generally, the effect of SBI, as per the most recent WHO recommendation,1 on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality has not been investigated in Ethiopia. Evidence regarding the effect of SBI is required for informed decision-making by policymakers and health programme planners. This paper aimed to assess the effect of SBI on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality using the most recent WHO definition and adjusting for a comprehensive set of potential confounders.

Methods

Study design and study area

This analysis used data from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2016. The EDHS is a nationally representative cross-sectional study conducted in nine geographical regions (Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Somali, Benishangul-Gumuz, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region, Gambela and Harari) and two administrative cities (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). A two-stage, stratified, clustered random sampling design was employed to collect data from women who gave birth within the 5 years preceding the survey. Further descriptions of the sampling procedure for the EDHS are presented elsewhere.5 A total of 8448 women who had at least two live births during the 5 years preceding the 2016 survey were included in the analysis. When women had more than two births in the 5 years preceding the survey, the birth interval between the most recent index child and the immediately preceding child was considered for all the study participants.

Variables

Outcome variables

The outcome variables in the current study were neonatal mortality (death of the child within 28 days of birth), infant mortality (death between birth and 11 months) and under-five mortality (death between birth and 59 months).5 43 These outcomes were coded as binary variables (1/0).

Treatment/exposure variable

SBI was the treatment variable and was defined as a birth-to-birth interval of less than 33 months as per the WHO definition.1 A preceding birth interval, the amount of time between the birth of the child under study (index child) and the immediately preceding birth, was considered in this study. Women’s birth interval data were collected by extracting the date of birth of their biological children data from the children’s birth/immunisation certificate, and/or asking for information regarding their children’s date of birth from the women. Mothers were asked to confirm the accuracy of the information before documenting children’s date of birth from children’s birth/immunisation certificates. This crosschecking was performed to avoid errors, since in some cases the documented birth date may represent the date when the birth was recorded, rather than the actual birth date. In the absence of children’s birth certificates, information regarding children’s date of birth was obtained from their mothers. Further information regarding birth interval data collection is provided elsewhere.2 3 44

Control variables

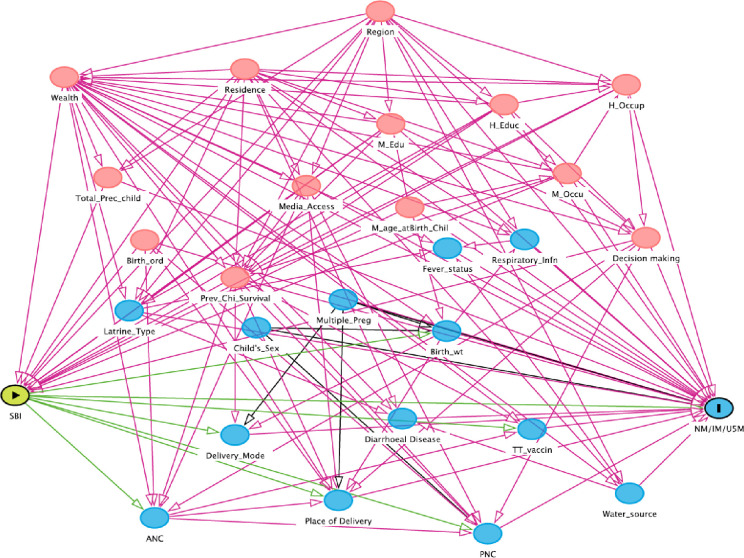

After reviewing relevant literature,2 18–21 23–25 28 29 39 45 46 direct acyclic graphs (DAGs) were constructed using DAGitty V.3.047 to identify confounders for the association between SBI and neonatal, infant and under-five child mortality. Adjustment for such confounders is necessary to estimate the unbiased effect of SBI on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality (figure 1). DAG is a formal system of mapping variables and the direction of causal relationships among them.48 49 This graphical representation of causal effects among variables helps understand whether bias is potentially reduced or increased when conditioning on covariates. Moreover, it illustrates covariates that lie in the causal pathway between the treatment and outcomes, which should not be included in the analysis as a confounder. These variables are indicated by green lines in figure 1. This is because a propensity score (PS) that includes covariates affected by the treatment (ie, variables on the causal pathway between treatment and outcome) obscures part of the treatment effect that one is trying to estimate.50 Identified confounders were maternal age at the birth of the index child, maternal education, maternal occupation, husband’s education, husband’s occupation, household wealth status, survival status of the preceding child, the total number of the preceding child, place of residence (urban/rural), regions, access to media and decision-making autonomy. A list of all variables considered in the DAG is provided in online supplemental material I.

Figure 1.

Direct acyclic graph used to select controlling variables. ANC, antenatal care; Birth_ord, birth order; Birth_wt, birth weight; H_Educ, husband education; H_Occup, husband occupation; IM, infant mortality; M_age_atBirth_chil, maternal age at birth of the index child; M_Edu, maternal education; M_Occu, maternal occupation; Multiple_preg, multiple pregnancy; NM, neonatal mortality; PNC, postnatal care; Prev_Chi_Survival, previous child survival; Respiratory_infn, respiratory infection; SBI, short birth interval; Total_Prec_child, total number of preceding child; TT_vaccin, tetanus toxoid vaccination status; U5M, under-five mortal.

bmjopen-2020-047892supp001.pdf (120.2KB, pdf)

A yellowish-green circle with a triangle at its centre indicates the main treatment/exposure variable, a blue circle with a vertical bar at its centre indicates the outcome variable, light red circles indicate ancestors of exposure and outcome (ie, confounders). Blue circles indicate the ancestors of the outcome variable. Green lines indicate a causal pathway. Red lines indicate open paths by which confounding may occur; this confounding can be removed by adjusting for one or several variables on the pathway.

Data analyses

Participants’ characteristics were described using frequency with per cent. P values were calculated using Pearson’s χ2 test. Given that the outcomes (ie, neonatal, infant and under-five mortality) were relatively infrequent, the unbiased effect of SBI on each outcome was estimated using PSs with a stabilised method of inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). A previous study51 has shown that IPTW with stabilised weights preserves the sample size of the original data, provides an appropriate estimation of the variance of the main effect and maintains an appropriate type I error rate. The other methods, such as IPTW with normalised weight and greedy algorithm with 1:1 matching methods, are discussed elsewhere.52–54 A PS is defined as the probability of treatment assignment given observed baseline covariates (described in online supplemental material II).54 PSs are used to estimate treatment effects on outcomes using observational data when confounding bias due to non-random treatment assignment is likely.50 IPTW weights the entire study sample by the inverse of the PS55; a differential amount of information is used from each participant, depending on their conditional probability of receiving treatment. This means observations are less likely to be lost than when using matching for confounder adjustment.56 57 PSs are a robust alternative to covariate adjustment when the outcome variable is rare, resulting in data sparsity and estimation issues in multivariable models.57 In this study, the weighted prevalence of the outcome variables of neonatal, infant and under-five mortality were 2.9% (95% CI=2.39% to 3.61%), 4.8% (95% CI=4.11% to 5.58%) and 5.5% (95% CI=4.73% to 6.44%), respectively.

bmjopen-2020-047892supp002.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

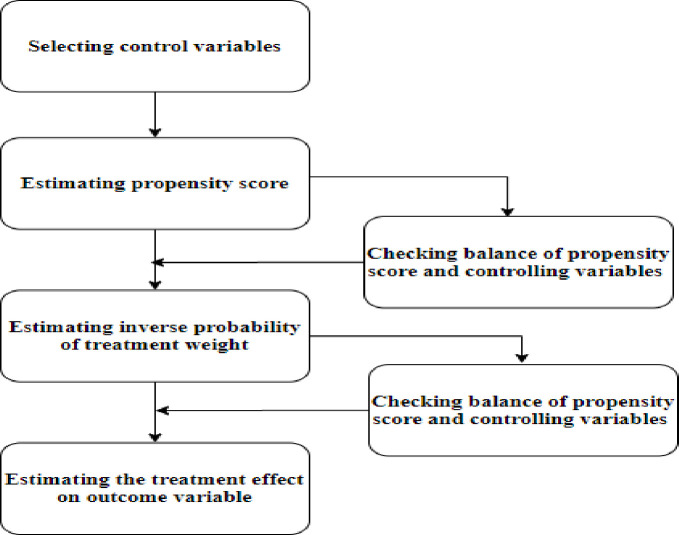

The analysis procedure was as follows. First, the PS was estimated using a logistic regression model in which treatment assignment (SBI vs non-SBI) was regressed on the 11 covariates identified using the DAG. The balance of measured covariates/confounders was then assessed across treatment groups (ie, women with SBI) and comparison groups (ie, women with non-SBI) before and after weighting, by computing standardised differences (online supplemental material II).57 58 For a continuous covariate, the standardised difference58 59 is defined as:

where and denote the sample mean of the covariate in treated and untreated subjects, respectively and and denote the corresponding sample variances of the covariate. The standardised difference58 59 for a dichotomous variable is given as:

where and denote the prevalence of the dichotomous variable in treated and untreated subjects, respectively.

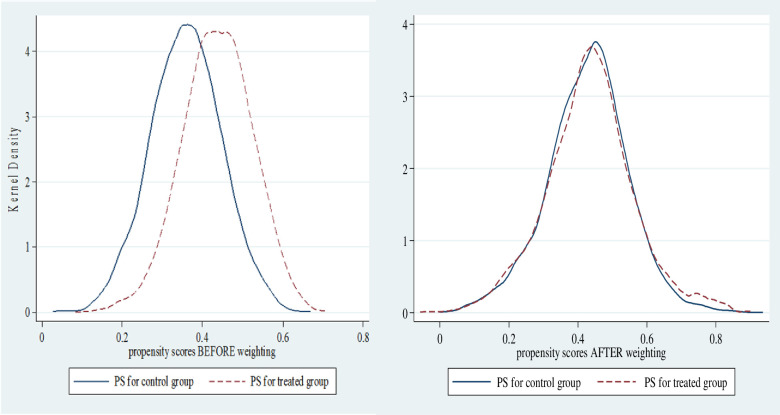

A standard difference <0.1 has been suggested as indicating a negligible difference in the mean or prevalence of a covariate between treatment and control groups and was used here.58 In addition, kernel densities were plotted to graphically demonstrate the PS balance in the treatment group (ie, women with SBI) and control groups (women with non-SBI). Balance in PSs was considered to be achieved when the kernel density line for the treatment group and control group lay closer together.60 The IPTWs was then calculated as 1/PS for those exposed to SBI and 1/(1−PS) for those who were not. The sample was then reweighted by the IPTW and the balance of the covariates checked in the reweighted sample.50 61 Stabilisation of weights was made to preserve the sample size of the original data, reduce the effect of weights of either treated subjects with low PSs or untreated subjects with high PSs, and improve the estimation of variance estimates and CIs for the treatment effect.51 Since the EDHS employed a two-stage, stratified, clustered random sampling, which is a complex sampling procedure, sampling weights were also used to adjust for the non-proportional allocation of sample participants to different regions, including urban and rural areas, and consider the possible differences in response rates.5 Finally, a weighted logistic regression was fit to estimate the effect of the treatment (SBI) on each outcome variable (neonatal, infant and under-five mortality). Estimation of the treatment effect on outcome variables in the final model used the grand weight, which was formed as the product of the survey weight and the stabilised weight. Literature has shown that combining a PS method and survey weighting is necessary to estimate unbiased treatment effects which are generalisable to the original survey target population.62 The treatment effect on the outcome variables was expressed as adjusted ORs (AORs) with a 95% CI. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata V.14 statistical software (StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release V.14. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP 2015). Figure 2 presents a schematic summary of the overall analysis procedure.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of the overall steps followed in the analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the general public were not involved in the design, or conduct or drafting of this secondary analysis.

Results

Respondents’ characteristics

Table 1 illustrates the baseline characteristics of the study participants. The occurrence of neonatal mortality differed with maternal age at birth, with mortality rates being higher among mothers aged ≥35 (p=0.021). Neonatal mortality was also higher in rural than in urban areas (p=0.004). Similarly, infant mortality and under-five mortality were somewhat higher in rural areas (p<0.001). Under-five mortality was higher among uneducated mothers (p=0.027) and in mothers without access to mass media (p=0.043). Mortality at all ages was higher among infants with at least five siblings (p<0.0001). Both infant and under-five mortality were slightly higher among women from the richer household

Table 1.

The weighted distribution of neonatal, infant and under-five child mortality by background characteristics, EDHS 2016

| Variable | Neonatal mortality | P value | Infant mortality | P value | Under-five Mortality | P value | |||

| No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | ||||

| Maternal age at the birth of the index child (in years) | |||||||||

| ≤19 | 291 (3.2) | 17 (5.8) | 0.021 | 283 (3.1) | 25 (6.5) | 0.065 | 280 (3.1) | 28 (6.0) | 0.068 |

| 20–24 | 1950 (23.4) | 52 (18.8) | 1896 (23.2) | 106 (23.7) | 1877 (23.3) | 125 (23.0) | |||

| 25–29 | 2587 (30.8) | 67 (26.0) | 2536 (30.8) | 118 (27.6) | 2516 (30.8) | 138 (27.4) | |||

| 30–34 | 1836 (22.7) | 59 (22.6) | 1802 (22.9) | 93 (21.0) | 1781 (22.7) | 114 (22.9) | |||

| ≥35 | 1533 (19.9) | 56 (26.8) | 1515 (20.0) | 74 (21.2) | 1500 (20.1) | 89 (20.7) | |||

| Maternal education | |||||||||

| Uneducated | 5890 (73.9) | 182 (75.0) | 0.859 | 5759 (73.8) | 313 (75.9) | 0.157 | 5694 (73.9) | 378 (75.5) | 0.027 |

| Primary | 1744 (22.0) | 54 (19.7) | 1715 (22.0) | 83 (20.8) | 1704 (22.0) | 94 (21.1) | |||

| Secondary+ | 563 (4.1) | 15 (5.3) | 558 (4.2) | 20 (3.3) | 556 (4.1) | 22 (3.4) | |||

| Maternal occupation | |||||||||

| Not employed | 5935 (72.9) | 178 (74.6) | 0.604 | 5807 (72.9) | 306 (73.2) | 0.575 | 5747 (72.9) | 366 (73.6) | 0.376 |

| Employed | 2267 (27.1) | 73 (25.4) | 2225 (27.1) | 110 (26.8) | 2207 (27.1) | 128 (26.4) | |||

| Husband education | |||||||||

| Uneducated | 4186 (49.9) | 145 (53.2) | 0.092 | 4104 (50.0) | 227 (50.1) | 0.346 | 4057 (50.0) | 274 (49.0) | 0.154 |

| Primary | 2482 (37.3) | 69 (34.6) | 2437 (37.3) | 114 (36.2) | 2416 (37.3) | 135 (37.1) | |||

| Secondary+ | 1529 (12.8) | 37 (12.2) | 1491 (12.7) | 75 (13.7) | 1481 (12.7) | 85 (13.9) | |||

| Husband occupation | |||||||||

| Not employed | 873 (7.7) | 22 (6.6) | 0.339 | 846 (7.6) | 49 (7.7) | 0.421 | 838 (7.6) | 57 (7.4) | 0.482 |

| Employed | 7324 (92.3) | 229 (93.4) | 7186 (92.4) | 367 (92.3) | 7116 (92.4) | 437 (92.6) | |||

| Wealth | |||||||||

| Poorest | 3238 (25.4) | 109 (15.6) | 0.248 | 3163 (25.3) | 184 (21.5) | 0.015 | 3118 (25.3) | 229 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| Poorer | 1430 (23.4) | 48 (22.5) | 1400 (23.4) | 78 (22.2) | 1390 (23.5) | 88 (21.3) | |||

| Middle | 1167 (21.1) | 36 (22.8) | 1147 (21.3) | 56 (20.0) | 1136 (21.2) | 67 (20.7) | |||

| Richer | 1025 (17.8) | 30 (24.8) | 1000 (17.7) | 55 (23.3) | 993 (17.6) | 62 (23.7) | |||

| Richest | 1337 (12.3) | 28 (14.3) | 1322 (12.3) | 43 (13.0) | 1317 (12.3) | 48 (12.1) | |||

| Total number of preceding child | |||||||||

| ≤2 | 2627 (31.0) | 57 (27.0) | <0.001 | 2591 (31.0) | 93 (27.1) | <0.001 | 2575 (31.1) | 109 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| 3–4 | 2561 (30.6) | 77 (22.0) | 2505 (30.7) | 133 (23.6) | 2482 (30.7) | 156 (24.6) | |||

| ≥5 | 3009 (38.4) | 117 (50.9) | 2936 (38.2) | 190 (49.3) | 2897 (38.2) | 229 (49.0) | |||

| Residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 1264 (8.8) | 22 (12.0) | 0.004 | 1251 (8.9) | 35 (8.7) | <0.001 | 1248 (9.0) | 38 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 6933 (91.2) | 229 (88.0) | 6781 (91.1) | 381 (91.3) | 6706 (91.0) | 456 (92.3) | |||

| Region | |||||||||

| Tigray | 765 (6.0) | 23 (6.1) | 0.516 | 762 (6.1) | 26 (4.1) | 0.145 | 752 (6.1) | 36 (5.3) | 0.039 |

| Afar | 808 (1.0) | 20 (0.7) | 779 (1.0) | 49 (1.2) | 762 (1.0) | 66 (1.4) | |||

| Amhara | 774 (18.7) | 26 (22.2) | 765 (18.8) | 35 (17.9) | 761 (18.9) | 39 (17.2) | |||

| Oromia | 1270 (44.7) | 37 (45.5) | 1245 (44.6) | 62 (47.9) | 1235 (44.6) | 72 (47.1) | |||

| Somali | 1231 (5.0) | 52 (6.3) | 1210 (4.9) | 73 (5.4) | 1203 (4.9) | 80 (5.1) | |||

| Benishangul-Gumuz | 711 (1.1) | 24 (1.0) | 690 (1.1) | 45 (1.3) | 682 (1.1) | 53 (1.4) | |||

| SNNPR | 1021 (21.2) | 23 (16.0) | 995 (21.1) | 49 (20.4) | 987 (21.1) | 57 (20.9) | |||

| Gambella | 541 (0.2) | 16 (0.2) | 531 (0.2) | 26 (0.2) | 522 (0.2) | 35 (0.2) | |||

| Harari | 443 (0.2) | 13 (0.2) | 429 (0.2) | 27 (0.2) | 427 (0.2) | 29 (0.2) | |||

| Addis Ababa | 246 (1.5) | 6 (1.2) | 245 (1.5) | 7 (1.0) | 245 (1.5) | 7 (0.8) | |||

| Dire Dawa | 387 (0.4) | 11 (0.4) | 381 (0.4) | 17 (0.4) | 378 (0.4) | 20 (0.4) | |||

| Access to mass media | |||||||||

| Yes | 1408 (15.8) | 36 (23.2) | 0.240 | 1383 (15.9) | 61 (20.2) | 0.177 | 1376 (15.9) | 68 (19.0) | 0.043 |

| No | 6789 (84.2) | 215 (76.8) | 6649 (84.1) | 355 (79.8) | 6578 (84.1) | 426 (81.0) | |||

| Decision-making autonomy | |||||||||

| Yes | 6014 (77.7) | 179 (74.9) | 0.469 | 5898 (77.8) | 295 (73.8) | 0.258 | 5848 | 345 | 0.072 |

| No | 2183 (22.3) | 72 (25.1) | 2134 (22.2) | 121 (26.2) | 2106 | 149 | |||

EDHS, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region.

Balance diagnostics

PS balance

Figure 3 presents the density plot of women in the treatment group (dashed lines) and the control group (solid lines) before and after weighting. It reveals that an adequate balance of the PS distribution between the treatment groups after weighting (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Balance of propensity scores (PS) before and after weighting across treatment and comparison groups.

Covariate balance

After weighting adjustment, standardised differences of covariates were all <0.1 (10%), showing comparability between women with and without SBI (online supplemental material II).

Treatment effect estimation

The prevalence of SBI in Ethiopia was 45.8% (95% CI=42.91% to 48.62%). Table 2 presents the estimated effects of SBI on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality. The adjusted estimated odds of neonatal mortality were 85% higher among women who experienced SBI (AOR=1.85, 95% CI=1.19 to 2.89) than those who did not. Similarly, the odds of infant mortality were two times higher (AOR=2.16, 95% CI=1.49 to 3.11) among women who experienced SBI compared with women who did not. The odds of under-five child mortality were two times (AOR=2.26, 95% CI=1.60 to 3.17) higher among women who were exposed to SBI compared with women who were not.

Table 2.

The effect of short birth interval on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016

| Treatment variable | Neonatal mortality | AOR (95% CI) | |

| No (%)* | Yes (%)* | ||

| Short birth interval | |||

| No | 4166 (54.5) | 95 (46.1) | Ref 1.85 (1.19 to 2.89) |

| Yes | 4031 (45.5) | 156 (53.9) | |

| Short birth interval | Infant mortality | ||

| No (%) | Yes (%) | ||

| No | 4126 (54.9) | 135 (40.5) | Ref |

| Yes | 3906 (45.1) | 281 (59.5) | 2.16 (1.49 to 3.11) |

| Short birth interval | Under-five mortality | ||

| No (%) | Yes (%) | ||

| No | 4099 (55.1) | 162 (39.3) | Ref |

| Yes | 3855 (44.9) | 332 (60.7) | 2.26 (1.60 to 3.17) |

*percentage are weighted.

AOR, adjusted OR; EDHS, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey; Ref, reference group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first comprehensive evidence regarding the effect of SBI on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality using the WHO recommendation to define SBI and applying rigorous analytical techniques to adjust for potential confounders. This study provides evidence that SBI is associated with neonatal, infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia. These findings will help policymakers and programme planners formulate targeted interventions to increase birth intervals and contribute to achieving the GTPE and SDGs target of reducing neonatal, infant and under-five mortality.15 16

In this current study, SBI was found to be associated with higher odds of neonatal mortality. This finding is consistent with evidence from the previous studies23 25 63–66 which have shown a higher risk of neonatal mortality among women with a SBI. However, the definition of SBI (ie, <33 months) used in the current study was in line with the WHO definition and longer than those used in previous studies (ie, ranges from <18 to 24 months). SBI could result in adverse neonatal child health outcomes, such as death, by causing maternal nutritional depletion, specifically folate depletion.67 68 The maternal nutritional depletion hypothesis states that a short birth-to-pregnancy/birth interval worsens the mother’s nutritional status because of inadequate time to recover from the physiological stresses of the subsequent pregnancy.69 This may compromise maternal nutritional status and ability to support fetal growth, which could result in fetal malnutrition and increased risk of infection and death during childhood.67 Women with SBI may also be less likely to attend postnatal care, which is vital for early detection and treatment of neonatal and maternal health problems. Evidence has shown that the majority of mothers and newborns in low-income and middle-income countries do not receive optimal postnatal care,70 yet close to half of the newborn deaths occurred within the first 24 hours after birth, a critical time where mothers and their babies should get their first postnatal care.71

Our study found that infant mortality was two times higher among women who experienced SBI compared with women who did not. Our finding was consistent with evidence from Ethiopia,18 32 Kenya,72 73 Nepal74 and Iran,75 although the cut-off point for SBI in the current study was longer than the previous studies. The abovementioned previous studies also documented that the risk of infant mortality was higher among women who experienced SBI compared with women who did not. One of the possible reasons for the effect of SBI on infant mortality could be low maternal motivation to breast feed (eg, if the pregnancy was unintended).76 Maternal perception of being undernourished due to a SBI may also influence her infant feeding choices, such as the duration and intensity of breast feeding and supplemental feeding of the infant. This could in turn affect infants’ nutritional status, their resistance to infection and may expose them to death.76–79 The abovementioned links between SBI and neonatal mortality also apply to infant mortality.

SBI doubled the odds of under-five mortality compared with non-SBI. Despite not using the WHO recommendation1 of less than 33 months to define SBI, the existing literature24 30 63 64 80 also supported our finding. The likely mechanism through which SBI affects under-five mortality could be competition between closely spaced siblings for limited household resources, maternal attention and cross-infection.76 Moreover, children born within a SBI may not receive their vaccination at all or complete their booster series, which is one of the risk factors that exposed children to the infectious disease and its associated death.81–83 Women with SBI could be burdened with caring for highly dependent children77 and other domestic activities. As a result, they may lack the time and motivation to take children to the health facility for vaccination and other services.

The results of this study need to be interpreted within the limitations of the observational study design. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, temporal associations between SBI and neonatal, infant and under-five mortality may not be established. The second limitation of our study could be associated with the non-randomised design of the study. PS-based analysis, IPTW, cannot account for unknown confounders in the same way that a randomised trial can. As a result, the effect of residual confounders may not be avoided. However, the application of IPTW mimics a randomised controlled trial by matching two comparison groups using a conditional probability of receiving exposure (SBI in this case) given a set of covariates. The study has also additional strengths, such as using data from a nationally representative survey with large sample size. The application of DAGs,48 49 84 a graphical tool used to identify minimum adjustment sets, which defined the set of explanatory variables for the PSs model was another strength of this study.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that SBI has a significant effect on neonatal, infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia. Interventions aiming to reduce neonatal, infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia should target the prevention of SBI. These could be achieved through creating awareness of the optimum birth interval and the negative impacts of shorter birth intervals on the health of children. Further expanding the availability and accessibility of family planning services also help women achieve optimum birth interval. Birth interval counselling as per the WHO recommendation should be integrated into the maternal and child health services as part of the child survival intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to The DHS Program for allowing us to use the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data for further analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors (DMS, CC, EH and DL) contributed to the design of the study and the interpretation of data. DMS performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors (DMS, CC, EH and DL) read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The dataset is available from The DHS Program repository at the following link: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Ethiopia_Standard-DHS_2016.cfm?flag=0.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The 2016 EDHS was approved by the National Research Ethics Review Committee of Ethiopia (NRERC) and ICF Macro International. Permission from The DHS Program was obtained to use the 2016 EDHS data for further analysis. This analysis was also approved by The University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2018-0332).

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing. Geneva, Switzerland, 2005: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shifti DM, Chojenta C, G Holliday E, et al. Individual and community level determinants of short birth interval in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0227798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shifti DM, Chojenta C, Holliday EG, et al. Application of geographically weighted regression analysis to assess predictors of short birth interval hot spots in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2020;15:e0233790. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shifti DM, Chojenta C, Holliday EG, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in short birth interval in Ethiopia: a decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1–13. 10.1186/s12889-020-09537-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF . Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grisaru-Granovsky S, Gordon E-S, Haklai Z, et al. Effect of interpregnancy interval on adverse perinatal outcomes--a national study. Contraception 2009;80:512–8. 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam I, Ismail MH, Nasr AM, et al. Low birth weight, preterm birth and short interpregnancy interval in Sudan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:1068–71. 10.3109/14767050903009222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen I, Jhangri GS, Chandra S. Relationship between interpregnancy interval and congenital anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:564:e1–564. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon S, Lazo-Escalante M, Villaran MV, et al. Relationship between interpregnancy interval and birth defects in Washington state. J Perinatol 2012;32:45. 10.1038/jp.2011.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheslack-Postava K, Liu K, Bearman PS. Closely spaced pregnancies are associated with increased odds of autism in California sibling births. Pediatrics 2011;127:246–53. 10.1542/peds.2010-2371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DaVanzo J, Razzaque A, Rahman M. The effects of birth spacing on infant and child mortality, pregnancy outcomes, and maternal morbidity and mortality in Matlab, Bangladesh. Technical Consultation and Review of the Scientific Evidence for Birth Spacing, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.DaVanzo J, Hale L, Razzaque A, et al. Effects of interpregnancy interval and outcome of the preceding pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in Matlab, Bangladesh. BJOG 2007;114:1079–87. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01338.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez RM, Gilleskie D. Infant mortality rate as a measure of a country's health: a robust method to improve reliability and comparability. Demography 2017;54:701–20. 10.1007/s13524-017-0553-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reidpath DD, Allotey P. Infant mortality rate as an indicator of population health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:344–6. 10.1136/jech.57.5.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UN . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development goal (A/RES/70/1), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Planning Commission . Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: growth and transformation plan II (GTP II) (2015/16-2019/20). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF . Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2019: key indicators. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abate MG, Angaw DA, Shaweno T. Proximate determinants of infant mortality in Ethiopia, 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health surveys: results from a survival analysis. Arch Public Health 2020;78:1–10. 10.1186/s13690-019-0387-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weldearegawi B, Melaku YA, Abera SF, et al. Infant mortality and causes of infant deaths in rural Ethiopia: a population-based cohort of 3684 births. BMC Public Health 2015;15:770. 10.1186/s12889-015-2090-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolde HF, Gonete KA, Akalu TY, et al. Factors affecting neonatal mortality in the general population: evidence from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS)-multilevel analysis. BMC Res Notes 2019;12:610. 10.1186/s13104-019-4668-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roro EM, Tumtu MI, Gebre DS. Predictors, causes, and trends of neonatal mortality at Nekemte referral Hospital, East Wollega zone, Western Ethiopia (2010-2014). retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seid SS, Ibro SA, Ahmed AA, et al. Causes and factors associated with neonatal mortality in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Jimma University medical center, Jimma, South West Ethiopia. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2019;10:39. 10.2147/PHMT.S197280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakgari N, Wencheko E. Risk factors of neonatal mortality in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2013;27:192–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fikru C, Getnet M, Shaweno T. Proximate determinants of Under-Five mortality in Ethiopia: using 2016 nationwide survey data. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2019;10:169. 10.2147/PHMT.S231608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mekonnen Y, Tensou B, Telake DS, et al. Neonatal mortality in Ethiopia: trends and determinants. BMC Public Health 2013;13:483. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Limaso AA, Dangisso MH, Hibstu DT. Neonatal survival and determinants of mortality in Aroresa district, southern Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2020;20:33. 10.1186/s12887-019-1907-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaya Y, Eide KT, Norheim OF, et al. Maternal and neonatal mortality in south-west Ethiopia: estimates and socio-economic inequality. PLoS One 2014;9:e96294. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebretsadik S, Gabreyohannes E. Determinants of under-five mortality in high mortality regions of Ethiopia: an analysis of the 2011 Ethiopia demographic and health survey data. Int J Popul Res 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/1602761 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negera A, Abelti G, Bogale T. An analysis of the trends, differentials and key proximate determinants of infant and under-five mortality in Ethiopia. Further Analysis of the 2000, 2005, and 2011 Demographic and Health Surveys. DHS Further Analysis Reports No 79 Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laelago T. Effects of preceding birth intervals on child mortality in Ethiopia; evidence from the demographic and health surveys, 2016. EIJ 2019;3. 10.23880/EIJ-16000119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hailemariam A, Tesfaye M. Determinants of infant and early childhood mortality in a small urban community of Ethiopia: a hazard model analysis. Ethiop J Health Dev 1997;11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dadi AF. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of short birth interval on infant mortality in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126759. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahle-Mariam Y, Berhane Y. Neonatal mortality among hospital delivered babies in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 1997;11. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolobo HA, Chaka TE, Kassa RT. Determinants of neonatal mortality among newborns admitted to neonatal intensive care unit Adama, Ethiopia: a case–control study. J Clin Neonatol 2019;8:232. 10.4103/jcn.JCN_23_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogale TN, Worku AG, Bikis GA, et al. Why gone too soon? examining social determinants of neonatal deaths in Northwest Ethiopia using the three delay model approach. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:216. 10.1186/s12887-017-0967-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woldeamanuel BT. Statistical analysis of neonatal mortality: a case study of Ethiopia. J Pregnancy Child Health 2018;05:1–11. 10.4172/2376-127X.1000373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asefa M, Drewett R, Tessema F. A birth cohort study in south-west Ethiopia to identify factors associated with infant mortality that are amenable for intervention. Ethiop J Health Dev 2000;14:161–8. 10.4314/ejhd.v14i2.9916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muluye S, Wencheko E. Determinants of infant mortality in Ethiopia: a study based on the 2005 EDHS data. Ethiop J Health Dev 2012;26:72–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deribew A, Tessema F, Girma B. Determinants of under-five mortality in Gilgel Gibe field research center, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2007;21:117–24. 10.4314/ejhd.v21i2.10038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bedada D. Determinant of under-five child mortality in Ethiopia. AJTAS 2017;6:198–204. 10.11648/j.ajtas.20170604.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ayele DG, Zewotir TT. Comparison of under-five mortality for 2000, 2005 and 2011 surveys in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2016;16:930. 10.1186/s12889-016-3601-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shamebo D, Sandström A, Muhe L, et al. The Butajira project in Ethiopia: a nested case-referent study of under-five mortality and its public health determinants. Bull World Health Organ 1993;71:389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.ICF International . Demographic and Health Survey Interviewer’s Manual. MEASURE DHS Basic Documentation No 2. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hailu D, Gulte T. Determinants of short Interbirth interval among reproductive age mothers in Arba Minch district, Ethiopia. Int J Reprod Med 2016;2016:6072437. 10.1155/2016/6072437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yohannes S, Wondafrash M, Abera M, et al. Duration and determinants of birth interval among women of child bearing age in southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:38. 10.1186/1471-2393-11-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, et al. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package 'dagitty'. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:1887–94. 10.1093/ije/dyw341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Attia JR, Oldmeadow C, Holliday EG, et al. Deconfounding confounding part 2: using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). Med J Aust 2017;206:480–3. 10.5694/mja16.01167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:70. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res 2014;49:1701–20. 10.1111/1475-6773.12182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, et al. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health 2010;13:273–7. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00671.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee Y, Hong I, Lee MJ, et al. Identifying risk of depressive symptoms in adults with physical disabilities receiving rehabilitation services: propensity score approaches. Ann Rehabil Med 2019;43:250. 10.5535/arm.2019.43.3.250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Austin PC, Mamdani MM. A comparison of propensity score methods: a case-study estimating the effectiveness of post-AMI statin use. Stat Med 2006;25:2084–106. 10.1002/sim.2328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Austin PC. A tutorial and case study in propensity score analysis: an application to estimating the effect of in-hospital smoking cessation counseling on mortality. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:119–51. 10.1080/00273171.2011.540480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo S, Fraser MW. Propensity score analysis: statistical methods and applications. SAGE publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deb S, Austin PC, Tu JV, et al. A review of propensity-score methods and their use in cardiovascular research. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:259–65. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34:3661–79. 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28:3083–107. 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 1985;39:33–8. 10.1080/00031305.1985.10479383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dugoff EH, Schuler M, Stuart EA. Generalizing observational study results: applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Serv Res 2014;49:284–303. 10.1111/1475-6773.12090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rutstein SO. Effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant and under-five years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the demographic and health surveys. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;89 Suppl 1:S7–24. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kozuki N, Walker N. Exploring the association between short/long preceding birth intervals and child mortality: using reference birth interval children of the same mother as comparison. BMC Public Health 2013;13 Suppl 3:S6. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rahman MM, Abidin S. Factors affecting neonatal mortality in Bangladesh. J Health Manag 2010;12:137–52. 10.1177/097206341001200203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ezeh OK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ, et al. Determinants of neonatal mortality in Nigeria: evidence from the 2008 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2014;14:521. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Castaño F, et al. Effects of birth spacing on maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health: a systematic review of causal mechanisms. Stud Fam Plann 2012;43:93–114. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rousso D, Panidis D, Gkoutzioulis F, et al. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on the health of mother and child. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;105:4–6. 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.King JC. The risk of maternal nutritional depletion and poor outcomes increases in early or closely spaced pregnancies. J Nutr 2003;133:1732S–6. 10.1093/jn/133.5.1732S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.WHO . Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health: postnatal care. Available: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/newborn/postnatal_care/en/ [Accessed 11 Jul 2020].

- 71.WHO, USAID, MCHIP . Postnatal care for mothers and newborns: highlights from the World Health Organization 2013 guidelines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Omariba DWR, Beaujot R, Rajulton F. Determinants of infant and child mortality in Kenya: an analysis controlling for frailty effects. Popul Res Policy Rev 2007;26:299–321. 10.1007/s11113-007-9031-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fotso JC, Cleland J, Mberu B, et al. Birth spacing and child mortality: an analysis of prospective data from the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. J Biosoc Sci 2013;45:779–98. 10.1017/S0021932012000570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lamichhane R, Zhao Y, Paudel S, et al. Factors associated with infant mortality in Nepal: a comparative analysis of Nepal demographic and health surveys (NdhS) 2006 and 2011. BMC Public Health 2017;17:53. 10.1186/s12889-016-3922-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.SHARIFZADEH GR, Namakin K, Mehrjoufard H. An epidemiological study on infant mortality and factors affecting it in rural areas of Birjand, Iran, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boerma JT, Bicego GT. Preceding birth intervals and child survival: searching for pathways of influence. Stud Fam Plann 1992;23:243–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ. Does birth spacing affect maternal or child nutritional status? A systematic literature review. Matern Child Nutr 2007;3:151–73. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00092.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stuebe A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009;2:222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016;387:475–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Biradar R, Patel KK, Prasad JB. Effect of birth interval and wealth on under-5 child mortality in Nigeria. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2019;7:234–8. 10.1016/j.cegh.2018.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:140–6. 10.2471/blt.07.040089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Innis BL, Snitbhan R, Kunasol P, et al. Protection against hepatitis A by an inactivated vaccine. JAMA 1994;271:1328–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arevshatian L, Clements C, Lwanga S, et al. An evaluation of infant immunization in Africa: is a transformation in progress? Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:449–57. 10.2471/blt.06.031526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Attia JR, Jones MP, Hure A. Deconfounding confounding part 1: traditional explanations. Med J Aust 2017;206:244–5. 10.5694/mja16.00491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047892supp001.pdf (120.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047892supp002.pdf (90.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The dataset is available from The DHS Program repository at the following link: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/Ethiopia_Standard-DHS_2016.cfm?flag=0.