Abstract

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease. The disease has a cell-mediated immune reaction which is precipitated by a specific trigger which turns the self-peptides antigenic. The role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in the malignant transformation of oral LP (OLP) has always been debated. Establishing a definitive part played by HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP, would possibly provide screening for the viruses, HPV vaccination, and antiviral therapy along with conventional treatment in LP which could improve prognosis. This systematic review is to assess the role of HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP. We performed a systematic search of PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google. The information was extracted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. All full-text papers that assessed the association of HPV in malignant transformation of OLP were considered eligible. The outcome parameter included the malignant transformation of OLP. We found a total of 19 studies from which five were found suitable for the review. Results from this systematic review showed HPV is associated with OLP. There is an increased prevalence of HPV in the erosive-atrophic (EA) variant of OLP compared to non-EA variant. There seems to be no strong evidence to prove the association between HPV and malignant transformation of OLP. Taking up the oncogenic potential of high-risk types and OLP as a potentially malignant disorder, more number of studies need to be performed on the dysplastic subtype of OLP and in those OLP lesions that progress to oral squamous cell carcinomas.

KEYWORDS: Dysplasia, human papillomavirus, malignant transformation, oral lichen planus

INTRODUCTION

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is an immune-mediated common chronic inflammatory disease seen mostly in the buccal mucosa, tongue, gingiva, and sometimes in the palate.[1] All types of OLP can be grouped under two clinical groups: erosive-atrophic forms (EA-OLP), including erosive, atrophic, bullous, and mixed EA variants; and non-EA forms (NON-EA-OLP), including papule, reticular, plaque, and mixed non-erosive atrophic variants.[2] EA-OLP are more prone to malignant transformation than non-EA-OLP. OLP affects middle-aged and has more female predilection. It affects about 0.5%–2.2% of the general population, varying according to geographic location.[3]

The etiology of OLP is still unclear and unknown; it is generally accepted to be a T-cell-mediated inflammatory disease.[1] It involves the degeneration of the epithelial basal cell layer, induced by cell-mediated immunologic reactions. The reaction of these specific CD8+T-cells is similar to what occurs during a viral infection, in which a virus acts as a cytoplasmic antigen. The association between certain human papillomavirus (HPV) and the development of various types of benign and malignant genital tumors is a well-perceived phenomenon.[4] In recent years, HPV has been identified in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) which suggests that HPV may be involved in oral carcinogenesis as well. The significant connection has been established between the presence of HPV antigens and the degree of dysplasia of premalignant disorders such as oral leukoplakia (OL).[5]

HPV is a small, nonenveloped, double-stranded, circular DNA virus with a diameter of 52–55 nm. The genome contains a double-stranded DNA molecule that is, bound to cellular histones and contained in a protein capsid without envelope.[5] The HPV-DNA genome encodes approximately eight open reading frames (ORFs). The ORF is divided into three functional parts: The early (E) region comprising 45% of the genome, the late (L) region extending for 40% of the genome and a long control region (LCR).[5,6,7] Early ORFs encode for E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7 proteins. These are needed for replication, cellular transformation, and the control of viral transcription. The late region is for encoding the structural proteins or capsid proteins that take part in virion assembly. LCR is necessary for viral DNA replication and transcription.[5,6,7]

Genotypic differences in the DNA base sequences of E6 and E7 genes permit stratification of the virus oncogenic phenotype into high- and low-risk type. High risk includes HPV-16,18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and low risk are HPV 6, 11, 42, 43, 44.5,7. Vaginal epithelium, penis, anal canal, vulva, cervix, perianal region, crypts of the tonsil, and oropharynx are the prevalent sites of HPV. HPV are characterized by a special tropism for squamous epithelial cells, keratinocytes. In the case of high-risk HPV infection, the viral genome is integrated into the host genome, which is the necessary event for the death of keratinocytes.[8,9] The most manifest function of the E6 protein is to promote the degradation of p53 through its interaction with a cellular protein, E6-associated protein. The p53 tumor suppressor gene itself regulates growth arrest and apoptosis after DNA damage.[8,10]

HPV might play a role in the malignant transformation of OLP.[11] HPV-16 and HPV-18 have been found to have an association with OLP.[12] Therefore; it is of interest to investigate the possibility of viral involvement in the malignant transformation of OLP.

This systematic review analyze the role of HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A systematic review was undertaken using objective and transparent methods as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, to identify, evaluate, and summarize all relevant research findings. The protocol for this review is not yet submitted to any registry. Taking into consideration the nature of the current study no approval by an institutional review board was necessary.

Research questions

The search for the systematic review began by defining the keywords in terms of the PICO format: (a) POPULATION, “oral lichen planus”; (b) INTERVENTION/EXPOSURE, “HPV”; (c) COMPARISON - Not applicable and OUTCOME, “malignant transformation”. The following research questions were fabricated for the keywords mentioned above: (a) Is there a significant prevalence of HPV DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) in OLP?; (b) Is HPV associated with dysplastic variant of OLP when compared to non-dysplastic variants of OLP?; (c) Is the presence of HPV associated with malignant transformation in OLP?

Selection criteria of studies

Inclusion criteria

Original studies on human papillomavirus (HPV) in OLP

Original case-control or cross-sectional studies

Clinical or histological diagnosis of OLP specified

Studies in the English language.

Exclusion criteria

Studies not done in OLP

Studies not done on HPV

Reviews and incomplete data.

Search category

A systematic search was performed in PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), Google, and Medline to screen relevant literature. Moreover, reference lists of previous meta-analyses and other relevant papers were manually searched to identify additional studies. The article search included only those from English Literature from the period 1985 to December 2019 entering the following terms: HPV or HPV, AND oral precancer or oral premalignancy or OLP, or oral dysplasia AND Malignant transformation or Malignant potential, as both medical subject heading terms and text words. In addition, an Internet search was also done using the keywords “Oral lichen planus” and “Human papillomavirus,” and “Dysplasia” and “Malignant transformation.”

Study selection

Study selection was conducted by two authors who independently screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion/exclusion criteria and identified relevant papers. Then the same two authors independently reviewed the full-text studies unable to be excluded by title and abstract alone. Comparison of papers was completed between the two authors with no disagreements regarding inclusion.

RESULTS

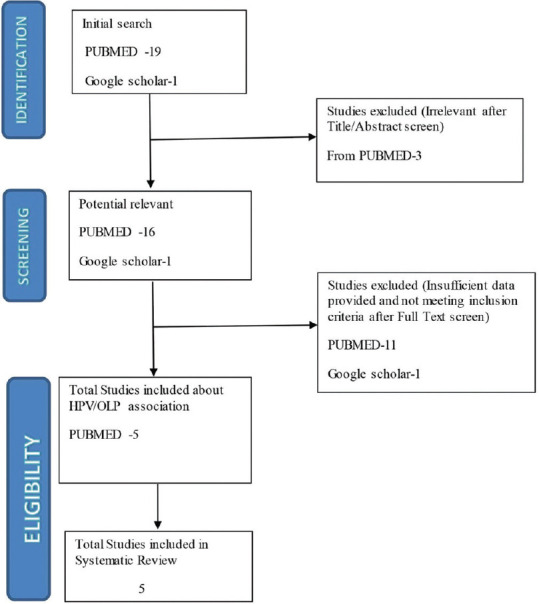

A meticulous search in PubMed, Medline, and Google scholar yielded a total of 19 articles. On reading the abstract, three articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. From the remaining 17 articles, 12 articles were excluded after reading the full text. Hence, a list of five articles was chosen for the final analysis. The selection procedure is presented as a flowchart in Figure 1 as per the PRISMA guidelines. Due to the heterogeneity of the reviewed studies and minimal articles obtained satisfying the inclusion criteria, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Yet a systematic review was done with the collected articles and the data obtained by doing so are tabulated and analyzed. The following details were recorded from each study: first author, publication date, clinical type of OLP, number of OLP patients and healthy controls, test methods, and HPV genotypes. The details of the selected studies are given in Tables 1–3.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart describing the identification, selection, and inclusion of studies

Table 1.

General description of the studies included

| Author | Year | Clinical type | Conditions assessed for HPV | Detection method | OLP (n/N) | Control (n/N) | HPV genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jontell et al.[13] | 1990 | OLP (e) | OLP | PCR, SBH | 13/20 | NA | HPV6, 11, 16 and 18 |

| Szarka et al.[14] | 2009 | EA-OLP, non-EA-OLP | OSCC, OLP.OL | PCR | 39/119 | 3/72 | HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 32, 33, 39, 51, 55, 57 |

| Mattila et al.[15] | 2012 | OLP (e) | OLP | Luminex-assay | 13/82 | NA | HPV6, 11, 16, 31, 33, 58, 66 |

| Sahebjamiee et al.[16] | NA | OLP | PCR | 11/40 | 5/40 | HPV16, 18 | |

| Gomez-Armayones et al.[17] | 2019 | NA | OLP, OSCC | PCR | 1/41 | NA | HPV16, HPV18 |

n: Numbers of HPV-positive subjects, N: Numbers of total subjects, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, SBH: Southern blot hybridization, NA: Not available, OLP(e): Erosive oral lichen planus, HPV: Human papillomavirus, OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, EA: Erosive-atrophic

Table 3.

Description of studies on comparison of human papillomavirus in dysplastic and nondysplastic oral lichen planus

Table 2.

Description of studies on human papillomavirus association in erosive oral lichen planus

| Author | Year | HPV positive cases in OLP (e) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Jontell et al.[13] | 1990 | 13/20 (65) |

| Szarka et al.[14] | 2009 | 26/61 (42.6) |

| Mattila et al.[15] | 2012 | 13/82 (15.9) |

OLP (e): Erosive oral lichen planus, HPV: Human papillomavirus

A total of five studies and 302 patients discussed the role of HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP. The study had middle-aged women as the predominant participants. All of the studies had not compared the results with normal buccal mucosa. One study had compared the association of HPV with LKP. Two studies had compared the HPV association with OSCC. Three studies discussed the association of HPV and the magnitude of malignant transformation in the erosive variant of OLP. Two studies compared the association of HPV in dysplastic and nondysplastic OLP.

Three studies had detected both high-risk and low-risk type HPV DNA in OLP and two studies had reported the association of only high-risk HPV types with OLP.

Study characteristics and interpretation of the results

Human papilloma virus prevalence in oral lichen planus

All five studies evaluated the prevalence of HPV in OLP.[13,14,15,16,17] Four studies used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect the prevalence of HPV in OLP.[13,14,15,16] One study had used Luminex-based assay for the detection of HPV.[15] One study by Jontell et al. had compared the prevalence of HPV from both PCR and Southern blot hybridization (SBH).[13]

In terms of detection of HPV DNA, two studies had quantitatively reported an increase in HPV DNA in OLP compared with normal oral mucosa.[14,16] One study compared HPV DNA in OLP with oral Leukoplakia (OL) and OSCC and had reported that HPV prevalence increased gradually with increasing severity of lesions as in OLP, OL, and OSCC, respectively.[14] One study found a low HPV-DNA attributable fraction in OLP compared to Dysplasia, suggesting that HPV is unlikely to play a significant role in oral carcinogenesis.[17]

The comparative study of the detection methods by Jontell et al. had reported that PCR assay had increased sensitivity in virus genome detection when compared with SBH.[13]

Human papilloma virus association with erosive oral lichen planus

A total of three studies reported the association of HPV with OLP (e).[13,14,15] Two studies were undertaken to examine the presence of HPV in OLPe and to determine the different DNA types.[13,15] However, they did not employ a comparison group. The study by Mattila et al. assessed HPV genotype in OLP (e) as related to DNA content and repair, proliferation activity, apoptosis, cell adhesion, and lymphocyte infiltration.[15] One study investigated the potential role of HPV in OL, EA-OLP, non-erosive atrophic OLP (non-EA-OLP), OSCC, and healthy oral mucosa.[14]

One study which had employed both PCR assay and SBH reported a high prevalence of HPV in the OLPe afflicted oral mucosa.[13] One study by Mattila et al. analyzed the HPV association with a subgroup of erosive OLP and reported that HPV is associated with OLP (e).[15] The authors also reported that cell proliferation index was higher in HPV positive samples and also associated with topoisomerase Iiα, caspase-3, and CD20 markers.

Szarka et al. had reported that there was an increase in HPV DNA in both EA-OLP and nonerosive atrophic OLP (non-EA-OLP) with significantly higher numbers in EA-OLP than non-EA-OLP. The authors have also compared the prevalence of HPV DNA with OL and OSCC and had reported no significant difference between EA-OLP and OL.[14]

Human papilloma virus association with malignant transformation of oral lichen planus

Three studies evaluated the association of HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP.[15,16,17] One study compared the presence of HPV in dysplastic and non-dysplastic OLP.[16] Two studies evaluated and compared the presence of HPV in OLP not malignized and OLP that turned to malignancy.[15,17]

Sahebjamiee et al. had reported that the HPV prevalence was higher in dysplastic than nondysplastic OLP lesions.[16] The study by Mattila et al. says that HPV prevalence was higher in non-dysplastic OLP than in dysplastic OLP lesions. However, the authors also reported the presence of HPV in OLP that turned malignant during follow-up.[15]

Gomez-Armayones et al. reported that there is no statistically significant association between HPV and OLP that turned to malignancy.[17]

DISCUSSION

LP is a chronic mucocutaneous disease. The prevalence of OLP in the Indian population is 2.6%.[18] The mean age of OLP onset is the fifth decade of life, and there is a gender predilection with a female/male ratio of 1.4:1.[19] OLP is considered a potentially malignant disorder with malignant transformation rate of 0.5%–2%.[20] The clinical presentation is almost always in a bilateral, symmetric pattern. The lesions are seen at the buccal mucosa, and other sites including the gingiva, tongue, and lip. Clinical features of OLP range from asymptomatic reticular white lesions in atrophic mucosa, to erosive-ulcerative areas accompanied by pain and discomfort, while the most characteristic feature is the presence of a lace-like network of fine white lines.[21]

OLP is a cell-mediated immune condition of unknown etiology, in which T-lymphocytes accumulate under the epithelium of the oral mucosa and increase the rate of differentiation of the stratified squamous epithelium, resulting in hyperkeratosis and erythema with or without ulceration.[1] Role of microorganisms has always been proposed, investigated, and debated in carcinogenesis. Predominantly, HPV is proven as the major etiological agent in uterine and cervical cancer. Recent studies have shown increase in the presence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers in nontobacco and alcohol users. HPV has been isolated from proliferative verrucous Leukoplakia which has a 95% chance of malignant transformation.[22] The role of HPV in premalignant lesions has also been studied.[11]

The papillomavirus family (Papillomaviridae) is a highly different group of viruses. Nineteen HPV types are referred to as genotypes on the basis of their sequence homology within the capsid protein gene L1, the most conserved gene within the genome. High-risk HPV proteins have high affinity for tumor suppressor proteins. HPVs specifically target the undifferentiated proliferative basal cells of epithelial mucosa that are exposed following tissue trauma. Continued and aberrant expression of the E6 and E7 genes of the HR-HPVs leads to genomic instability and mutational events that can result in malignant transformation.[2,23,24,25] Until now, few follow-up studies exist on the progression of oral potentially malignant disorders toward malignancy and the role of HPV remains contradictory.[26,27,28] This systematic review aims at detecting the role of HPV in malignant transformation of OLP.

Jontell et al. in his study examined the prevalence of HPV 6, 16 in OLP (e) and they concluded that HPV may represent one of the risk factors along with carcinogens like tobacco and alcohol for oral squamous cell carcinoma in OLP (e). The authors observed that trauma plays an essential role in the introduction of HPV into the basal cell layer of the epithelium in the initiation of the infection. It is understood that widespread breakdown of the weakened epithelium in OLP (e), the tissue is constantly exposed to various insults and recovery which might contribute to a malignant transformation. However, above study did not investigate HPV infection in patients with OLP (e) that had actually transformed into OSCC.[13]

Traditionally, the 1st line of treatment of symptomatic OLP is local immunosuppression by corticosteroids which is used widely to keep OLP under control. There are reports of malignant transformation of OLP (e) followed by long-term treatment with corticosteroids. Steroids are known to decrease the density of Class II antigen-expressing Langerhans cells. Thus continuous use of these immunosuppressants may open entry to viral antigens and an increased risk of malignant transformation.[2,13]

Szarka et al. reported a higher HPV prevalence in EA-OLP which was similar to that found in OL. The authors were of opinion that HPVs may be involved in the development or progression of not only OSCC but also in malignant progression of potentially malignant oral disorders.[14] Several types of cytogenetic and epigenetic alterations were found in the malignant transformation of OLP. Molecular changes such as loss of p53 gene mediated by HPV E6 oncoproteins may represent a potential marker for identifying the malignant transformation of OLP.[2,14]

Mattila et al. reported that HPV is associated with OLP (e).[15] Sahebjamiee et al. studied the prevalence of high-risk HPV-16 and HPV-18 in tissue and saliva samples from an Iranian population diagnosed with OLP. The authors found tissue biopsies (27.5%) to be more reliable than saliva analysis (7.5%) in detecting HPV presence. The authors also suggested that dysplastic OLP lesions had a higher HPV prevalence than nondysplastic OLP lesions and that high-risk HPV-16 is more frequently present in dysplastic OLP lesions.[16] Gomez-Armayones et al. found a low HPV-DNA attributable fraction in premalignant lesions of the oral cavity. The authors suggested that HPV is unlikely to play a significant role in oral carcinogenesis.[17]

This systematic review showed that HPV is associated with OLP. HPVs may play some etiological role in the malignant progression of OLP. However, the accurate role of HPV in the transformation to malignancy remains unclear. More prospective cohort studies are needed to confirm the role of HPV as an etiological agent of OLP and its transformation to malignancy.

Limitations

The major limitation of this systematic review is the number of articles reviewed is minimal. This is due to the limitation of studies available on the role of HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP. Various systematic reviews were carried to find out the association of HPV in OLP. We tried to find the association of HPV in the malignant transformation of OLP. English literature articles and those with full-text availability were only considered in this review. The five articles evaluated in this review used three kinds of HPV detection methods: PCR, SBH, and Luminex-based assay.[13,14,15,16,17] Three studies did not have a control group for comparison.[13,15,16] Due to multiple study designs, risk of bias cannot be scientifically calculated. However in general the detection and selection biases of the selected studies limit the usefulness of these results. The heterogeneity and lower level of evidence within the included studies limited the statistical analyses of the data.

CONCLUSION

The epidemiology of OSCC arising from OLP is not well defined. Molecular alterations detected in OLP can be useful biomarkers for predicting the progression into malignancy. Moreover, a uniform research standard should be established to produce more convincing results. Follow-up studies are needed to understand if the natural histories of HPV-infected OLP lesions differ from those without HPV infection for its malignant transformation. However, taking into account the oncogenic potential of high-risk HPV-types, OLP patients should be screened for the presence of this virus, and adequate long-term follow-up should be conducted in lesions that are found to be positive.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein JB, Wan LS, Gorsky M, Zhang L. Oral lichen planus: Progress in understanding its malignant potential and the implications for clinical management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:32–7. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorsky M, Epstein JB. Oral lichen planus: Malignant transformation and human papillomavirus: a review of potential clinical implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:461–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCartan BE, Healy CM. The reported prevalence of oral lichen planus: A review and critique. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:447–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez JV, Gutierrez RA, Keszler A, Colacino Mdel C, Alonio LV, Teyssie AR, et al. Human papillomavirus in oral lesions. Medicina. 2007;67:363–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syrjänen S, Lodi G, von Bültzingslöwen I, Aliko A, Arduino P, Campisi G, et al. Human papillomaviruses in oral carcinoma and oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2011;17:58–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prabhu SR, Wilson DF. Human papillomavirus and oral disease – Emerging evidence: A review. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:2–10. doi: 10.1111/adj.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Villiers EM, Gunst K. Characterization of seven novel human papillomavirus types isolated from cutaneous tissue, but also present in mucosal lesions. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1999–2004. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.011478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1263–9. doi: 10.1086/597755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ragin C, Edwards R, Larkins-Pettigrew M, Taioli E, Eckstein S, Thurman N, et al. Oral HPV infection and sexuality: A cross-sectional study in women. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:3928–40. doi: 10.3390/ijms12063928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreimer AR, Alberg AJ, Daniel R, Gravitt PE, Viscidi R, Garrett ES, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection in adults is associated with sexual behavior and HIV serostatus. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:686–98. doi: 10.1086/381504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jand R, Syrjanen S. Human papilloma virus infections in the oralmucosa. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:905–14. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axell T, Rundqvist L. Oral lichen planus – A demographic study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:52–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jontell M, Watts S, Wallström M, Levin L, Sloberg K. Human papilloma virus in erosive oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:273–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szarka K, Tar I, Fehér E, Gáll T, Kis A, Tóth ED, et al. Progressive increase of human papillomavirus carriage rates in potentially malignant and malignant oral disorders with increasing malignant potential. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24:314–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattila R, Rautava J, Syrjänen S. Human papillomavirus in oral atrophic lichen planus lesions. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:980–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahebjamiee M, Sand L, Karimi S, Biettolahi JM, Jabalameli F, Jalouli J. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oral lichen planus in an Iranian cohort. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19:170–4. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.164528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez-Armayones S, Chimenos-Küstner E, Marí A, Tous S, Penin R, Clavero O, et al. Human papillomavirus in premalignant oral lesions: No evidence of association in a Spanish cohort. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanemitsu S. Oral lichen planus: Malignant potential and diagnosis. Oral Sci Int. 2014;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Zhao ZZ, Zhou XJ, Khan A, et al. The pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:350–65. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattsson U, Jontell M, Holmstrup P. Oral lichen planus and malignant transformation: Is a recall of patients justified? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:390–6. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirasuna K. Oral lichen planus: Malignant potential and diagnosis. Oral Sci Int. 2014;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong DT, Münger K. Association of human papillomaviruses with a subgroup of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:675–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanley MA, Pett MR, Coleman N. HPV: from infection to cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1456–60. doi: 10.1042/BST0351456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–75. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreimer AR, Bhatia RK, Messeguer AL, González P, Herrero R, Giuliano AR. Oral human papillomavirus in healthy individuals: A systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:386–91. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c94a3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen H, Norrild B, Vedtofte P, Praetorius F, Reibel J, Holmstrup P. Human papillomavirus in oral premalignant lesions. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B:264–70. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(96)00011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang SW, Lee YS, Chen TA, Wu CJ, Tsai CN. Human papillomavirus in oral leukoplakia is no prognostic indicator of malignant transformation. Cancer Epidemiol. 2009;33:118–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]