Abstract

Cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids are abused in spite of possible adverse health consequences. The current study investigated the reinforcing effects of an ecologically relevant mode of administration (inhalation) of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of cannabis, and three synthetic cannabinoids detected in synthetic cannabinoid products (JWH-018, JWH-073, and HU-210) in non-human primates (NHPs). Male and female (N = 4 each) rhesus macaques were trained to inhale warm air via a metal stem to receive a candy reinforcer, an alcohol aerosol vehicle was then paired with the candy. Dose-dependent responding for inhaled aerosols of THC (2.0–16.0 ug/kg/inhalation), JWH-018 (0.2–1.6 ug/kg/inhalation), JWH-073 (2.0–8.0 ug/kg/inhalation), and HU-210 (1.0–8.0 ug/kg/inhalation) was established using a fixed-ratio 5 schedule of reinforcement and compared to vehicle (alcohol) self-administration. Dose-dependent responding for inhaled heroin (25.0–100.0 ug/kg/inhalation), a known reinforcer in NHPs, was also established. Responding approximated vehicle levels for many drug doses tested, but at least half of the monkeys responded for ≥ one dose of each cannabinoid and heroin above vehicle, with the exception of THC. Drug deliveries calculated as percent vehicle followed a prototypical inverted-U shaped dose-response curve for cannabinoids and heroin except for THC and JWH-018 (in males). Grouped data according to sex demonstrated that peak percent of vehicle reinforcers earned for THC was greater in males than females, whereas peak percent of vehicle reinforcers earned for JWH-018, HU-210, and heroin were greater in females than males. These findings indicate minimal reinforcing effects of CB1 receptor agonists when self-administered by NHPs via aerosol inhalation.

Keywords: THC, Synthetic cannabinoids, Cannabis, Abuse-liability, Reinforcement, Vapor

INTRODUCTION

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs), commonly referred to as ‘Spice’ or ‘K2’, are a group of abused drugs that were first identified in the United States in 2008. Despite the accumulation of reports pointing to the severe adverse effects of SCs, they continue to be used. While diverse arrays of compounds are contained in these products, they have been identified primarily as cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) agonists, similar to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of cannabis. In addition to their intoxicating effects, SCs are used for a variety of reasons including as a substitute for cannabis because of their low costs, easy availability and the fact that they are not detected in standard urine toxicology tests (i.e., Cooper 2016). Despite their widespread use, little is known regarding the reinforcing effects of SC compounds relative to THC.

When SCs first emerged, primary compounds identified in SC products were the naphthoylindoles JWH-018 and JWH-073 (Auwärter et al., 2009; Castaneto et al., 2014; Wiley et al., 2014) that have distinct pharmacological profiles from THC. Although JWH-018 and JWH-073 are CB1 receptor agonists (Atwood et al., 2010, 2011; Wiley et al., 2014) in vitro (Wiley et al., 1998), studies in laboratory animal studies (Ginsburg et al., 2012; Järbe et al., 2011) demonstrate that they have different pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profiles from THC and these differences suggest that the compounds pose greater risk for abuse and dependence than THC. Studies in rodents (Järbe et al., 2011) and non-human primates (Ginsburg et al., 2012) indicate that these compounds have a faster onset and shorter duration of action than THC. JWH-018 and JWH-073 have THC-like discriminative-stimulus effects and reduce the discriminative stimulus effects associated with cannabinoid withdrawal (Gatch & Forster, 2014; Ginsburg et al., 2012; Järbe et al., 2011; Marshell et al., 2014; Rodriguez & McMahon, 2014; Wiley et al., 1998, 2014). Of note, JWH-073 displays approximately 10-fold lower potency and lower efficacy than JWH-018 in these assays (Atwood et al., 2011; Ginsburg et al., 2012) suggesting that JWH-018 is a full agonist while JWH-073 is a partial agonist at the CB1 receptor. The relatively short duration of action of the compounds suggest the potential for greater frequency of self-administration than cannabis (Renner, 1964; Winger et al., 2002). The higher efficacy of JWH-018 may increase its reinforcing effectiveness further (Mello et al., 1988) and may also be responsible for greater dependence liability than cannabis (Ginsburg et al., 2012). In addition to the JWH compounds, HU-210, a dimethylheptyl analog of THC has also been detected in Spice products (Hruba & McMahon, 2014; Mechoulam & Feigenbaum, 1987). HU-210 is also more potent and efficacious than THC at the CB1 receptor, yet its onset of action is significantly slower and the duration of action is nearly 5 times longer (Burkey et al., 1997; Hruba & McMahon, 2014); thus HU-210 is hypothesized to be less reinforcing than the JWH compounds and THC.

The current study sought to assess the reinforcing effects of JWH-018, JWH-073, and HU-210, three synthetic cannabinoids with distinct pharmacodynamic properties, and compare these effects to THC. THC’s reinforcing effects are unreliable or weak across oral (Barrus et al., 2018) and intravenous (Wakeford et al., 2017) routes of administration in rodents. While intravenous THC self-administration has been somewhat more reliable in non-human primates (John et al., 2017; Justinova et al., 2003), inhalation (smoking and vaporizing) are the most common modes of cannabis and SC use in humans (i.e., Shiplo et al. 2016; Smart et al. 2017). As such, this study assessed the reinforcing effects of THC and SC via intrapulmonary vapor (aerosol) inhalation. Intrapulmonary heroin self-administration was also assessed as a positive control (Foltin & Evans, 2001). Earlier studies of aerosolized drug self-administration in non-human primates revealed sex dependent effects with greater drug-reinforced responding in females (Foltin & Evans, 2001; Foltin, 2018). With respect to CB1 receptor agonist effects, female rodents are more sensitive to a range of CB1 receptor agonist outcomes compared to males including their abuse-related effects (i.e., (Cooper & Craft, 2018), an effect that extends to humans (Cooper & Haney, 2014). Whether these effects generalize to non-human primates is unknown. Therefore, a second goal of the current study was to explore potential differences in cannabinoid self-administration as a function of sex.

METHODS

Subjects:

Experimentally- and drug-naïve adolescent female (N = 4) and male (N = 4) rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), initially weighing 4.0 to 5.6 kg, were housed unrestrained for the duration of the study in a room that was maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with lights on at 7 AM. Monkeys grew appropriately as the study progressed obtaining final weights between 5.3 to 9.9 kg for females and males respectively. Every day monkeys received fruit, a daily vitamin, and monkey chow to maintain a stable body fat composition; approximately 7–9 chow (105–135 grams; High protein monkey diet #5047, 3.37 kcal/g; LabDiets®, PMI Feeds, Inc., St. Louis, MO) and periodically received various food treats such as peanuts. Monkeys were individually housed in customized, squeeze-capable, rack-mounted, non-human primate cages (Hazleton Systems, Inc, Aberdeen, MD) in the AAALAC-approved animal care facility of The New York State Psychiatric Institute. Each monkey had access to 2 identically sized chambers (61.5 cm wide x 66.5 cm deep x 88 cm high) connected by a 40 cm x 40 cm opening. Water was freely available from spouts located on the back panels of both chambers. Investigators and veterinarians routinely monitored the health of the monkeys. The cages were positioned to allow all monkeys to have visual, auditory and olfactory social contact with other monkeys, the animal caretakers and other staff. Monkeys had multiple positive interactions each day with the caregivers and investigators and had other various forms of environmental enrichment including music, cartoon videos, a puzzle box, a mirror, and other tactile and chew toys. Self-administration sessions occurred in the cages using custom response panels mounted to the front of the home cage for the duration of the session. The onset and duration of menstruation was recorded for female monkeys throughout the study. All study procedures and aspects of animal maintenance complied with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

Operant training and self-administration sessions:

Monkeys were trained to suck on a brass pipe that activated a pressure-sensitive relay to receive a fruit-flavored juice reinforcer. The fruit-flavor juice was taken away once established sucking ('puffing') behavior was established and sucking on the brass pipe led to drug or vehicle vapor delivery. A glass stem inside the brass mouth piece was heated to the temperature to be used for the drug vapor inhalation sessions as detailed below, and monkeys puffed on the brass pipe to generate sufficient air pressure to activate the pressure-sensitive relay (accompanied by a tone) to receive a candy using a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement. The vehicle for the vapor drug was then introduced (0.05 ml of 95% ETOH), and puffing behavior continued to be reinforced with candy, followed by THC and JWH-018; contingencies were systematically varied to establish stable responding on an FR5 schedule of reinforcement paired with a candy reinforcer. Vapor delivery was signaled by a pair of lights over the pipe stem and controlled by a micro-pneumatic, peristaltic pump connected to a drug reservoir mounted on the outside of the panel next to a tone generator. The drug delivery system, similar to that used by humans when smoking cocaine (Foltin et al., 1990) was fitted within the pipe (Boni et al. 1991; Foltin and Evans 2001): a glass tube (10 mm) fitted with a screen for catching drug fluid after it is dropped into the stem was set inside another glass tube (12 mm) mounted on the outside of the panel. The external pipe was wrapped by a heating coil encased in fiberglass insulation and connected to a heat controller. The heat source was maintained at a temperature of 180°-190°C. The monkeys inhaled on the brass pipe with enough force to activate the pressure-sensitive relay (accompanied by a tone) according to the contingency, which activated a pressure-sensitive switch that operated the drug pump. The pump delivered 0.05 ml of a 95% ethanol solution (vehicle) containing THC, JWH-018, JWH-073, HU-210, or heroin on the screens in the pipe, causing it to aerosolize and be pulled into the monkey’s lungs as the monkey continued to puff (i.e., inhale). A tone sounded and the lights (CM 1820, 24 v, Chicago Miniature, Buffalo Grove, IL) above the pipe flashed with each puff providing visual and auditory feedback.

For the current study, the reinforcing effectiveness of THC (2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16.0 ug/kg/delivery), JWH-018 (0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 ug/kg/delivery), JWH-073 (2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 ug/kg/delivery), HU-210 (1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 ug/kg/delivery), and heroin (25.0, 50.0 and 100.0 ug/kg/delivery) using an FR5 schedule of aerosol reinforcement was assessed. Thirty minute sessions occurred on weekday mornings. When the session commenced, the first two aerosol deliveries were both paired with a single mini M&M (1 calorie [1/3rd of a regular M&M], such that 5 puffs were required for each of these two initial candy reinforcers. Four additional candy deliveries followed a progressive ratio schedule with subsequent candy deliveries requiring 15, 20, 25, and 30 puffs; aerosol deliveries remained on an FR5 schedule of reinforcement such that these candy deliveries occurred with the 5th, 9th, 14th, and 20th aerosol deliveries. A maximum of 6 candies were delivered per session with no candies delivered after the 20th aerosol delivery. This method was similar to earlier studies that used candy reinforcers to improve training of puffing behavior needed for smoked or aerosolized drug self-administration (i.e., Foltin, 2018; Pieper & Cole, 1973). Schedule contingencies were controlled by customized software (Eureka Software, Cary, NC) running on two Macintosh 610 computers (Cupertino, CA) located in an adjacent area. Drug doses were tested until responding stabilized, which was defined as three consecutive sessions with individual session responding that did not differ by more than 45% of the average of these sessions. There were some instances when stability according to this definition was not attained, mostly due to very low responding (i.e., aerosol deliveries earned during one of the three sessions were 0 and the other two sessions were 2 deliveries). There were also three instances when average stable responding was derived from fewer than three sessions because of equipment malfunction and one instance of a health concern that paused behavioral testing for that dose in that monkey. Generally, vehicle self-administration was assessed between each drug dose; the next drug dose was introduced once vehicle responding was stable. The order of drug testing was as follows: heroin, THC, JWH-018, JWH-073, and HU-210. Doses were presented in a semi-random order with mid or highest doses for each drug tested first. All monkeys received the drugs and doses in the same order with two exceptions when some monkeys were presented with one mid-range JWH-018 dose first (i.e., 0.4 ug/kg/delivery) and the others receiving the other mid-range dose first (0.8 ug/kg/delivery).

Drugs:

All drugs were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and were dissolved in 95% ethanol. Dose selection for cannabinoids were based on previous behavioral work done with these compounds and previous conversions of intravenous (i.v.) behaviorally active doses of psychoactive drugs to inhaled doses. In human and non-human primates, the dose ratio of i.v. to smoked drug that produces equivalent behavioral effects is about 1:2 for a range of drugs (Foltin & Fischman, 1991; Meng, 1999; Perez-Reyes et al., 1991; Woolverton et al., 1984). As such, we used a 1:2 ratio in estimating dose range. Squirrel monkeys self-administer i.v. THC at a rate that exceeds vehicle across a range of doses (2–8 ug/kg/infusion), with maximum responding occurring at 4 ug/kg/infusion (Justinova et al., 2003; Tanda et al., 2000): we therefore examined a dose range of 2–16 ug/kg/inhalation of THC. The ED50s for the acute discriminative stimulus effects for THC, JWH-073, and JWH-018 in rhesus monkeys is 0.044, 0.058, and 0.013 mg/kg respectively (Ginsburg et al., 2012), and HU-210 is estimated to be 7.1 times more potent than THC (Hruba & McMahon, 2014). Therefore, the range of JWH-073 doses tested was 2–8 ug/kg/inhalation (similar to THC), 0.2–1.6 ug/kg/inhalation for JWH-018, and 1–8 ug/kg/inhalation for HU-210. Heroin doses were adjusted to obtain an inverted-U dose-response function and were lower than in an earlier report (Foltin & Evans, 2001).

Data Analysis:

For each drug dose tested, aerosol deliveries and responding for approximately three sessions of stable responding were averaged for individual monkeys and according to sex. Sessions of stable vehicle responding (baseline) generally obtained between doses were averaged for each monkey for each drug and according to sex. Aerosol deliveries and responding for active drug doses were considered to be higher or lower than vehicle based on differences of the standard errors of the means. Aerosol drug deliveries were also calculated as a function of percent baseline vehicle deliveries for individual monkeys for each drug. Number of aerosol drug deliveries and responses made, calculated as percent vehicle, were averaged according to sex. Although the onset and duration of menstruation was recorded for female monkeys each day on a calendar for the duration of the study, data could not be analyzed as a function of menstrual cycle phase due to the many drug and dose conditions in the current study,

RESULTS

Cannabinoid Self-administration:

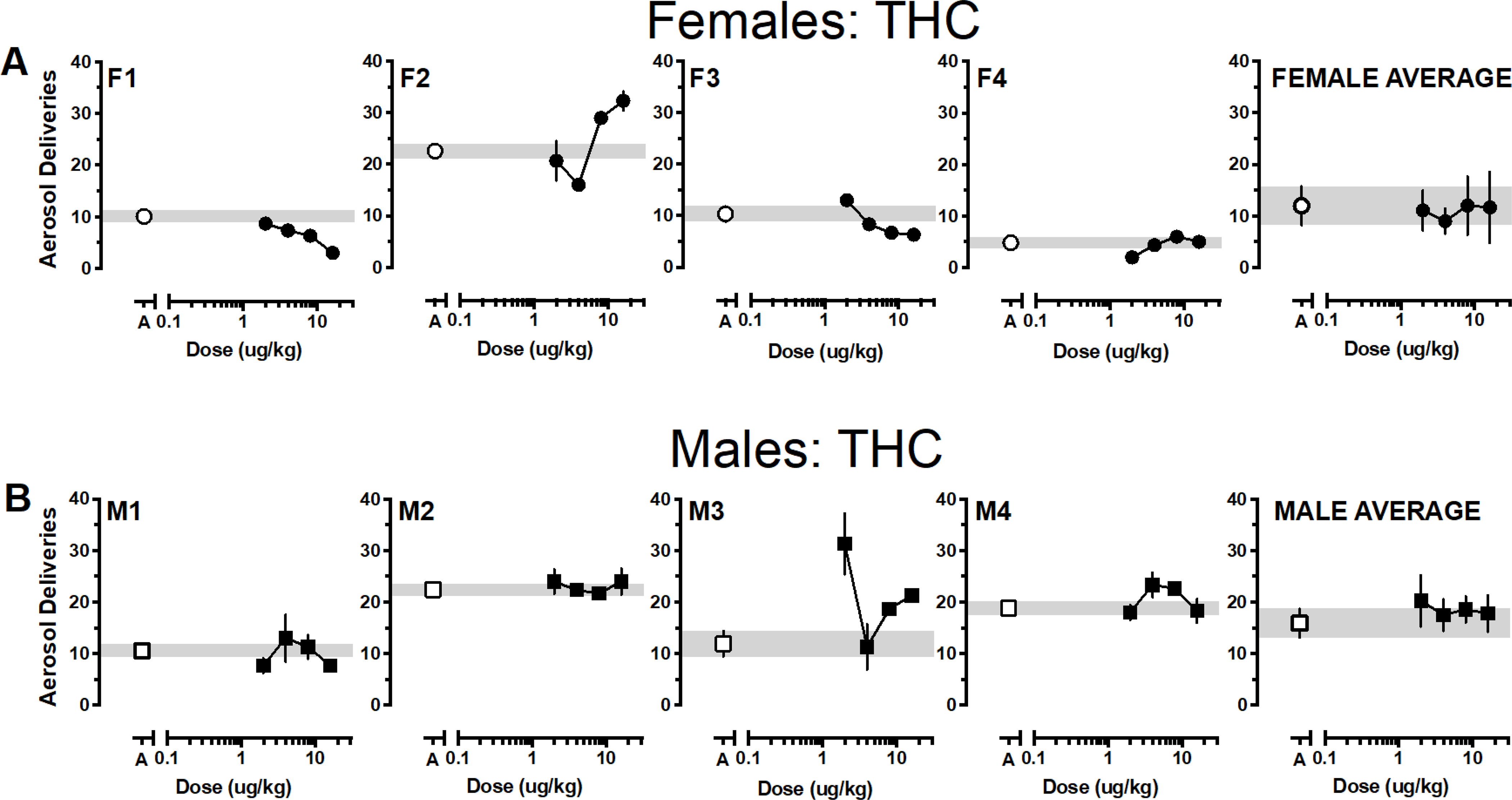

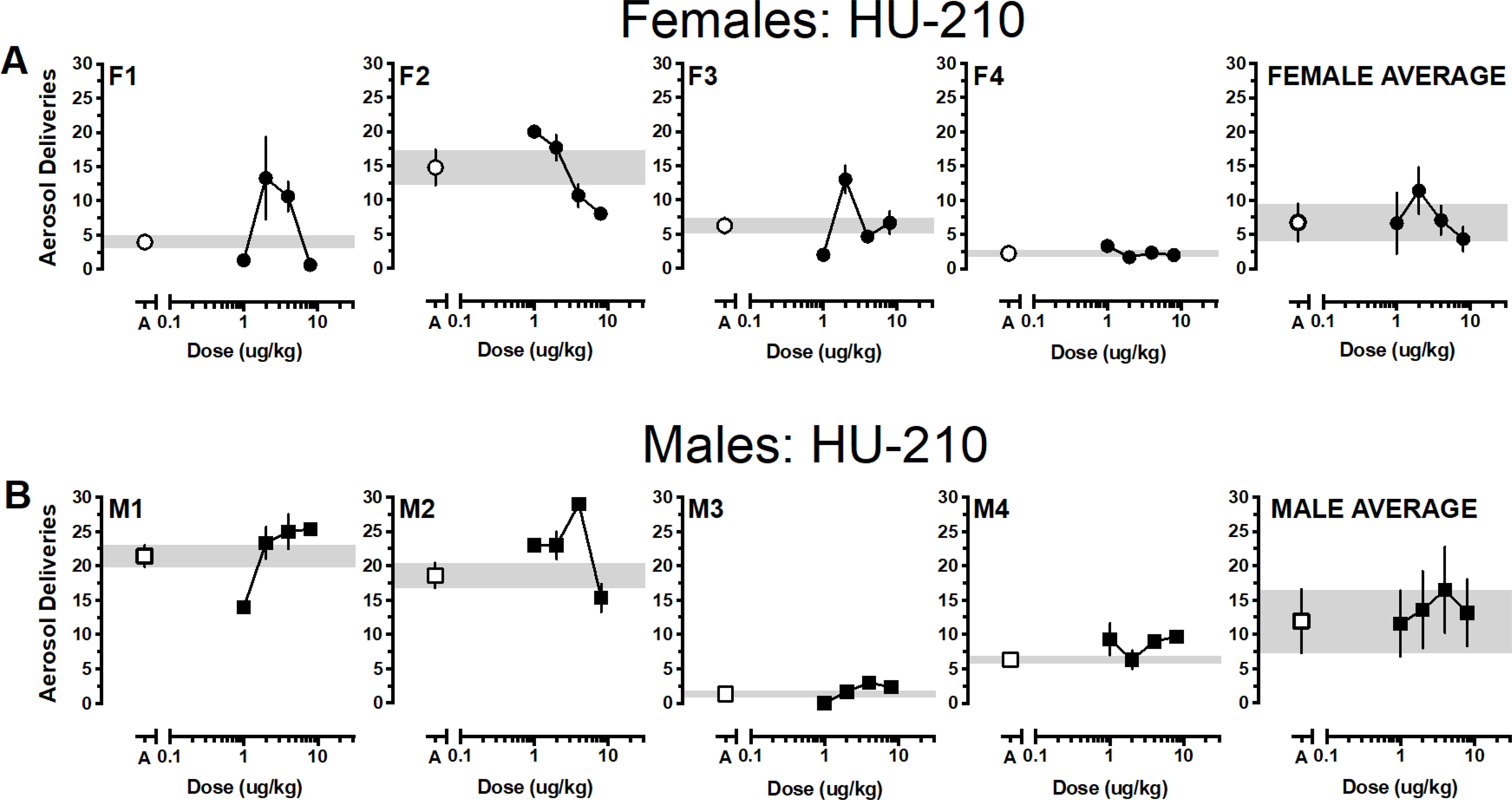

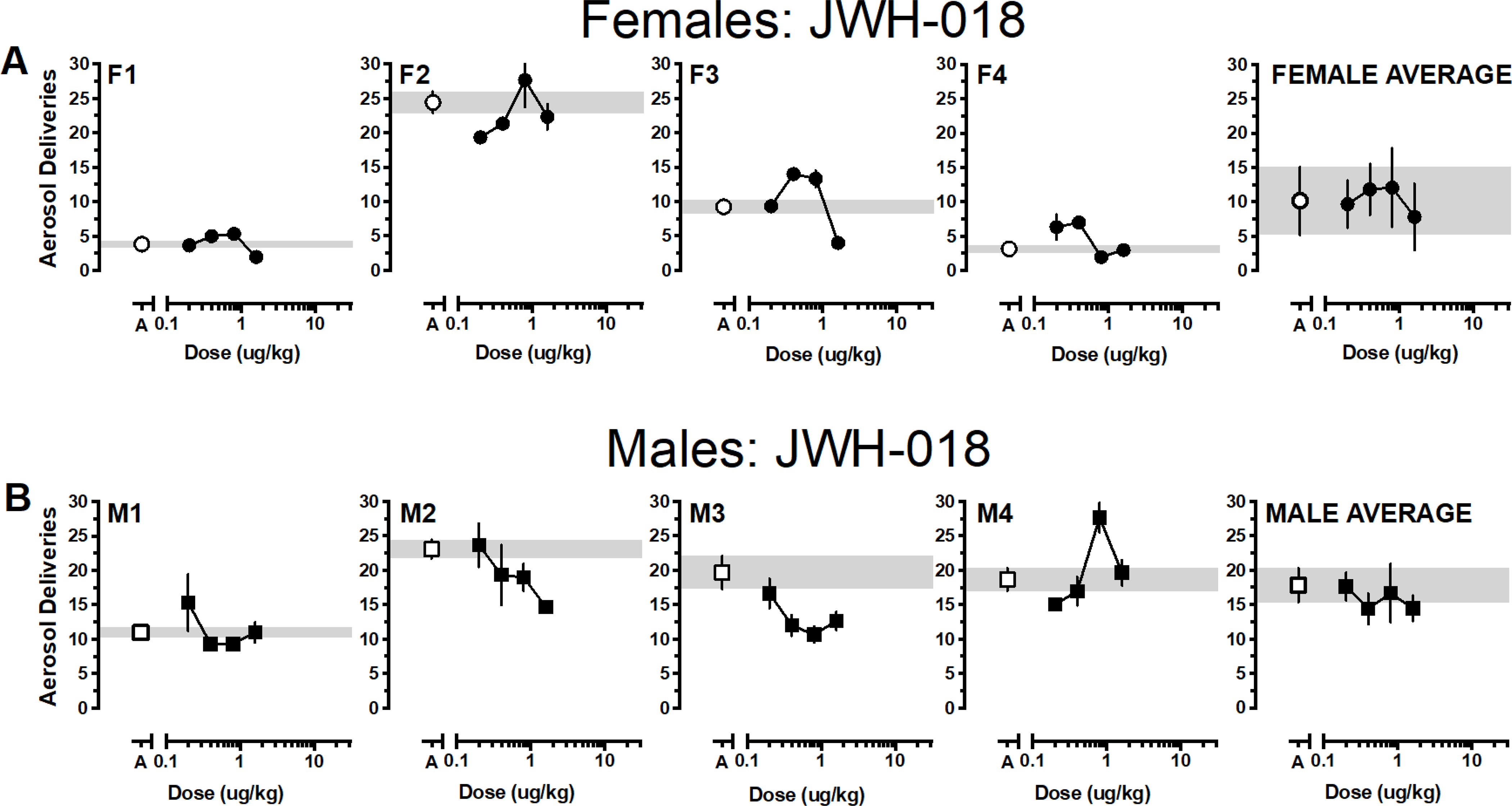

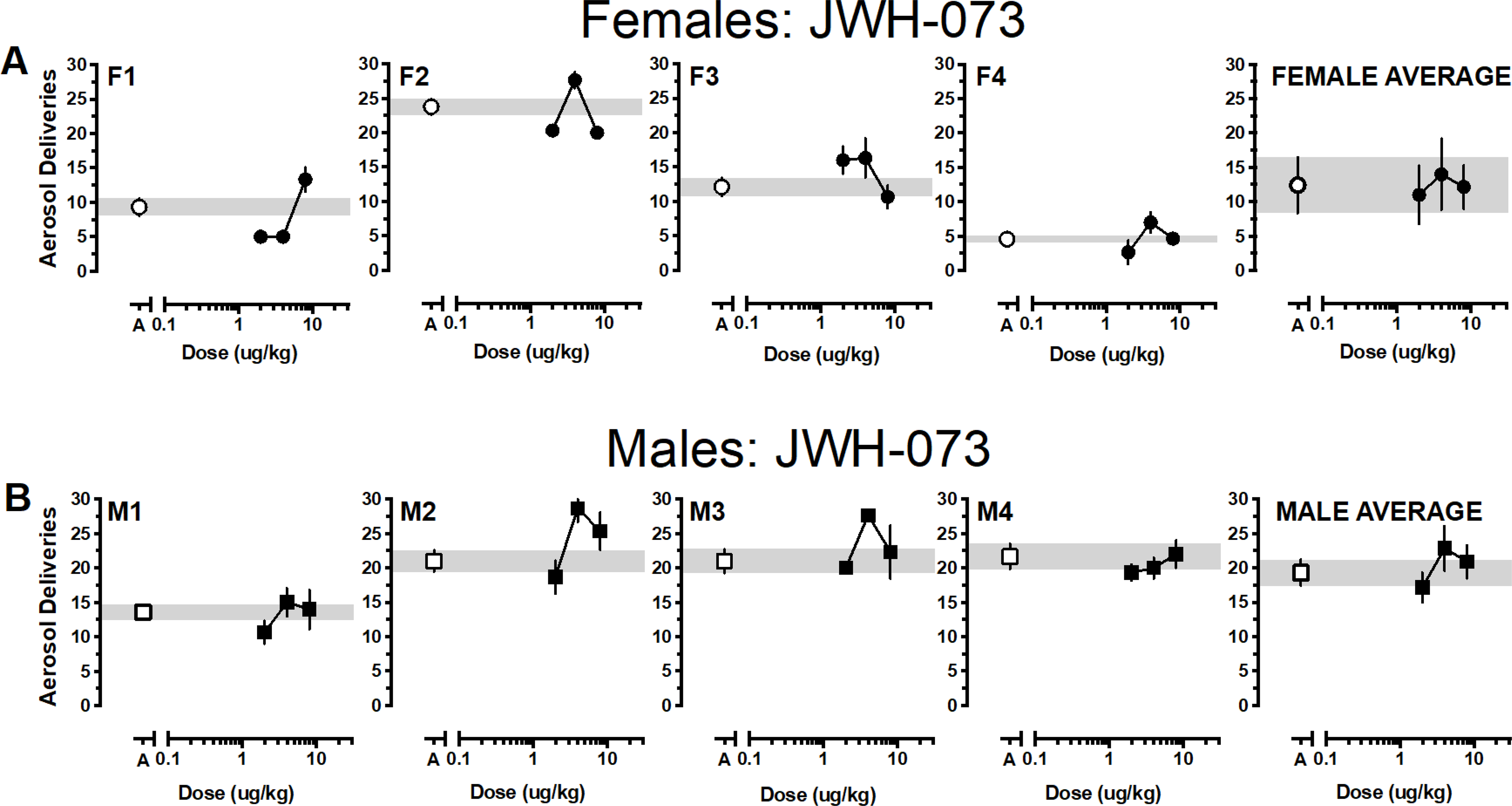

Reinforcers earned as a function of dose and cannabinoid for individual monkeys and averaged according to sex are depicted in Figures 1–4 with females in the top panels and males in the bottom panels. Generally, responding approximated vehicle levels for most doses across the various cannabinoids with responding above vehicle levels for 1 or 2 doses and below vehicle levels for 1 or 2 doses. Only one female responded for THC above vehicle baseline (F2) and all females responded for at least one THC dose below vehicle levels. Responding was more robust in males; at least two THC doses were self-administered above vehicle levels by two males (M3, M4) and only one male responded for THC below vehicle levels (M1) (Figure 1). Group responding averaged according to sex indicated that THC responding approximated vehicle levels for both males and females. Almost the opposite pattern was observed when JWH-018 was available (Figure 2). Three females responded for at least one JWH-018 dose above vehicle levels (F1, F3, F4); three females also responded for one to two JWH-018 doses below vehicle levels. Only a single dose of JWH -018 was self-administered above vehicle by one male (M4) and all males responded for one to three JWH-018 doses below vehicle levels. Group responding averaged according to sex indicated that JWH-018 responding approximated vehicle levels. By contrast, at least one JWH-073 dose was self-administered above vehicle levels by all females and only two females responded for JWH-073 below vehicle levels (F1, F2) (Figure 3). Two male monkeys self-administered JWH-073 above vehicle levels (M2, M3) and none responded below vehicle levels. While this responding resulted in an inverted-U dose response function when averaged for both male and female monkeys, values for the groups approximated vehicle responding. A similar pattern of results was seen when HU-210 was substituted for vehicle, with 75% of female (F1, F2, F3) and male (M1, M2, M4) monkeys responding for at least one HU-210 dose above vehicle levels (Figure 4). Responding below vehicle levels was also observed for up to two HU-210 doses in females (F1, F2) and one dose in two males (M1, M2). Similar to the other cannabinoids, when HU-210 data were averaged according to sex, values for the groups approximated vehicle responding.

Figure 1.

Average (± SEM) aerosol deliveries earned as a function of THC dose for individual female (1A, •) and male (1B, ■) monkeys. Aerosol deliveries earned averaged according to sex (± SEM) depicted in the right panels. Average (± SEM) vehicle aerosol deliveries are indicated by open symbols (○ for females, □ for males) and gray bar.

Figure 4.

Average (± SEM) aerosol deliveries earned as a function of HU-210 dose for individual female (4A, •) and male (4B, ■) monkeys. Aerosol deliveries earned averaged according to sex (± SEM) depicted in the right panels. Average (± SEM) vehicle aerosol deliveries are indicated by open symbols (○ for females, □ for males) and gray bar.

Figure 2.

Average (± SEM) aerosol deliveries earned as a function of JWH-018 dose for individual female (2A, •) and male (2B, ■) monkeys. Aerosol deliveries earned averaged according to sex (± SEM) depicted in the right panels. Average (± SEM) vehicle aerosol deliveries are indicated by open symbols (○ for females, □ for males) and gray bar.

Figure 3.

Average (± SEM) aerosol deliveries earned as a function of JWH-073 dose for individual female (3A, •) and male (3B, ■) monkeys. Aerosol deliveries earned averaged according to sex (± SEM) depicted in the right panels. Average (± SEM) vehicle aerosol deliveries are indicated by open symbols (○ for females, □ for males) and gray bar.

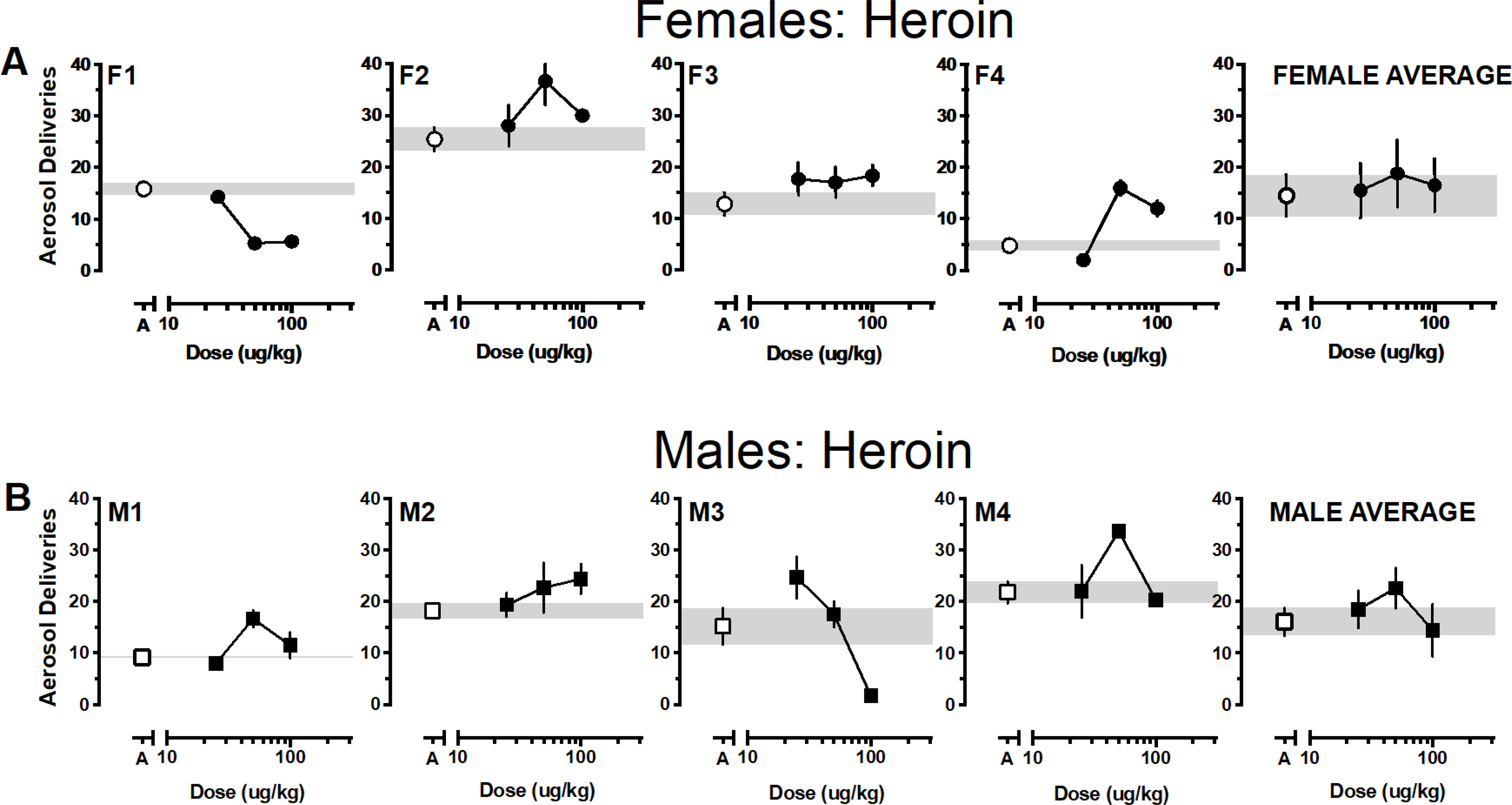

Heroin Self-administration:

At least 1 heroin dose was self-administered above vehicle levels by three of the four females and was the only drug tested that supported responding above vehicle levels for all male monkeys. Unlike the cannabinoids, few monkeys responded for heroin below vehicle levels (F1, F4, M3) (Figure 5). The single female (F1) that failed to respond for any dose of heroin above the vehicle baseline also failed to respond for THC. While data averaged according to sex resulted in an inverted-U shaped dose-response function when averaged for both male and female monkeys, values approximated vehicle levels.

Figure 5.

Average (± SEM) aerosol deliveries earned as a function of heroin dose for individual female (5A, •) and male (5B, ■) monkeys. Aerosol deliveries earned averaged according to sex (± SEM) depicted in the right panels. Average (± SEM) vehicle aerosol deliveries are indicated by open symbols (○ for females, □ for males) and gray bar.

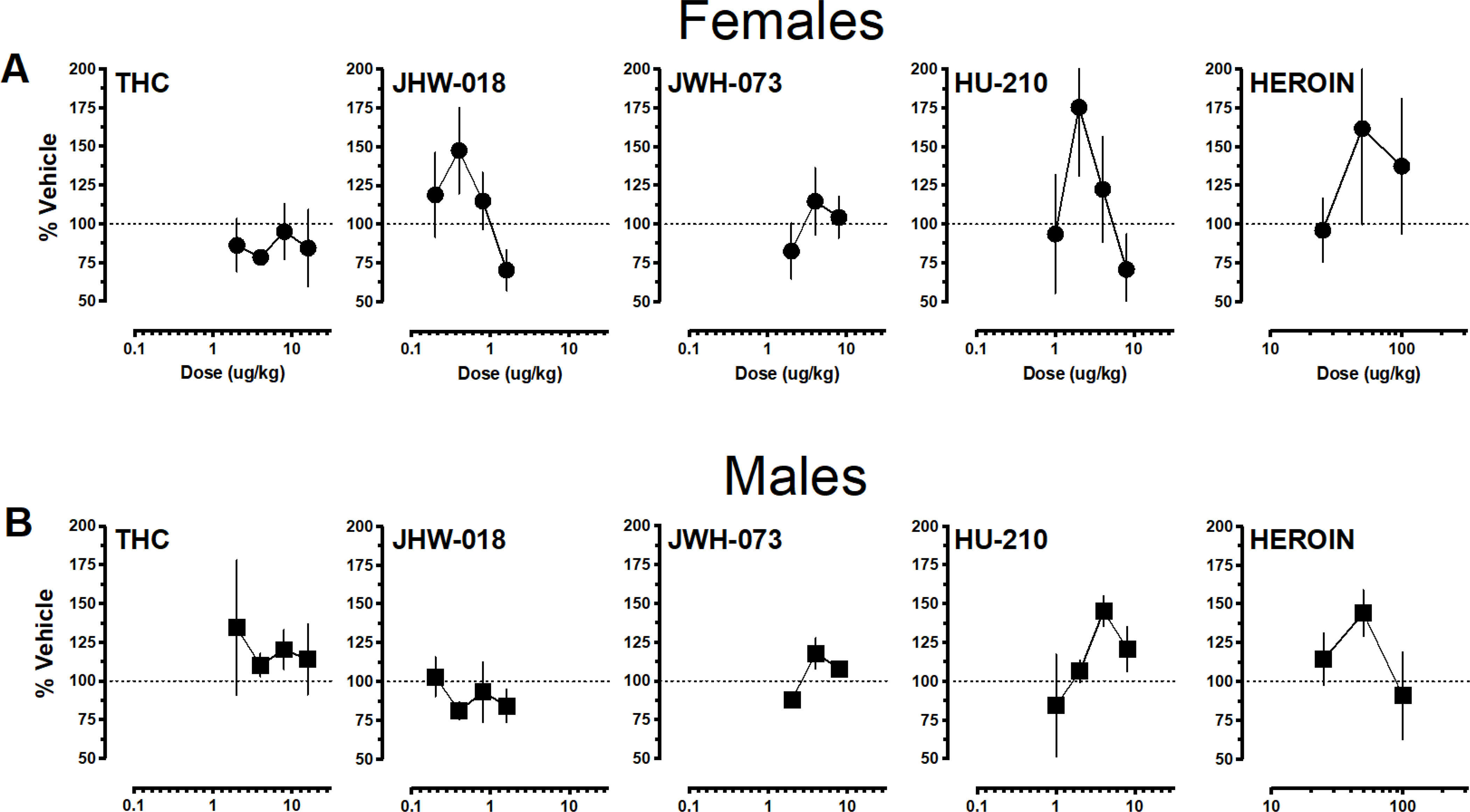

Self-administration as percent vehicle:

Figure 6 illustrates group average drug deliveries as a function of drug (THC, JWH-018, JWH-073, HU-210, and heroin), dose, and sex as percent of the vehicle (females, upper panels; males lower panels). Average aerosol deliveries earned calculated as percent vehicle for each monkey followed an inverted-U shaped dose-response function for most drugs tested. Intermediates doses supported peak behavior for JWH-018, HU-210, and heroin in females and JWH-073, HU-210, and heroin in males. Aerosol deliveries earned for THC did not exceed the vehicle baseline for females, and deliveries earned for JWH-018 in males either approximated vehicle (two doses) or were below vehicle (two doses). Across drugs tested, HU-210 (2.0 ug/kg) maintained peak responding for females. In males, HU-210 (4.0 ug/kg) and heroin (50.0 ug/kg) maintained nearly equivalent peak responding compared to the other drugs tested.

Figure 6.

Average (± SEM) aerosol deliveries delivered for each active drug dose calculated as percent of the vehicle for each drug. Data depicted as a function of drug (THC, JWH-018, JWH-073, HU-210, and heroin) and sex (females in 6A, • and males in 6B, ■).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the relative reinforcing effects of aerosolized SCs compared to THC in female and male rhesus monkeys using a mode of administration that parallels the most common methods of cannabis and SC use (smoking and vaporizing). Heroin aerosol self-administration was tested as a positive control to validate the current procedure; indeed, 7 of 8 monkeys self-administered 1 or more doses of heroin aerosol. Half of the monkeys responded for at least one dose of each cannabinoid above vehicle levels, with the exception of THC; however, at least half of the monkeys also responded below vehicle levels for at least one dose of each cannabinoid, except for JWH-073. Reinforcers earned followed a prototypical inverted-U shaped dose-response curve for at least 50% of the females and males for 3 of the 4 cannabinoids tested but vehicle and dose-dependent drug responding was not consistent across monkeys. Monkey-specific responding was also not consistent across cannabinoids; some monkeys responded for some doses of some cannabinoids but not others. As a group, some cannabinoid aerosols maintained responding above vehicle levels when calculated as percent baseline with differences emerging between females and males. There were dose-dependent effects for nearly all monkeys and all drugs confirming that the procedure, even though candy reinforcement also occurred, was sensitive to the varying pharmacologies of the drugs tested.

In the current study, self-administered aerosolized drug and vehicle were paired with candy following a progressive ratio procedure such that a candy was paired with the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 9th, 14th and 20th aerosol deliveries; candy was not paired with subsequent aerosol deliveries. This procedure was similar to an earlier study in baboons assessing the reinforcing effects of aerosolized methamphetamine where each delivery was paired with a candy (Foltin, 2018). In that study, responding decreased for methamphetamine compared to vehicle in males whereas responding increased for methamphetamine compared to vehicle in most females. Here, responding exceeded vehicle for at least one dose of JWH-073 and HU-210 in 75% of the group (≥ 50% of males and females) suggesting that certain cannabinoids are more consistently reinforcing across sexes compared to methamphetamine (Foltin, 2018). In earlier studies of aerosolized heroin self-administration in rhesus monkeys, it was possible to initiate and maintain heroin self-administration in the absence of candy pairings (Evans et al., 2003; Foltin & Evans, 2001). In the current study, attempts to initiate cannabinoid self-administration in the absence of candy pairings were unsuccessful (data not shown) pointing to cannabinoids’ weaker reinforcing effects relative to heroin in the earlier study. Once self-administration was initiated and stabilized, assessing maintenance in the absence of the candy delivery would have been the next step in determining the strength of cannabinoid-reinforced behavior in comparison to heroin in the current study.

JWH-018 and JWH-073 were hypothesized to be more reinforcing than THC; JWH-018 is a higher efficacy CB1 receptor agonist compared to THC, and both JWH-018 and JWH-073 are characterized to have a faster onset and shorter duration of action compared to THC (Atwood et al., 2011; Brents et al., 2011; Ginsburg et al., 2012; Hruba et al., 2012; Järbe et al., 2011). HU-210 was hypothesized to be the least reinforcing given its slow onset and long duration of action (Burkey et al., 1997; Hruba & McMahon, 2014). Session duration (30 minutes) and frequency (daily on weekdays) were consistent across drugs and therefore not adjusted for the potential impact of pharmacokinetic differences across cannabinoids. As expected, THC appeared to be the least reinforcing cannabinoid with only 40% of the group responding for a THC dose above vehicle and all females responding below vehicle for at least one THC dose, suggesting that certain doses were aversive. Contrary to our hypotheses, HU-210 maintained responding above vehicle in 75% of the group and elicited the highest response rates compared to the other cannabinoids when calculated as percent vehicle responding. Only 50% of the group responded for a dose of JWH-018 above vehicle whereas 90% exhibited lower responding for multiple doses of JWH-018, a surprising result surprising given evidence in rodents and non-human primates of JWH-018’s reinforcing effects (De Luca et al., 2015; Maguire & France, 2020). This pattern was in contrast to responding for JWH-073, a lower efficacy agonist than JWH-018 with proposed similar pharmacokinetics; 75% responded for at least one JWH-073 dose above vehicle and only 25% percent responded for a JWH-073 dose below vehicle. Of note, self-administration of one cannabinoid by individual monkeys did not necessarily predict self-administration of another. For instance, the only female that self-administered THC above vehicle (F2) was also the only female that did not self-administer any JWH-018 dose above vehicle. Similarly, M3 responded for three of the four THC doses tested above vehicle, but did not respond for any doses of JWH-018 or HU-210, the cannabinoid that elicited the highest relative responding compared to vehicle for the group. To summarize, self-administration was reinforced by some doses of cannabinoids tested, while others appeared to be aversive; these effects were not consistent across different drugs within individual monkeys.

Previous studies in non-human primates have had little success in establishing THC’s reinforcing effects via i.v. administration (i.e., Justinova et al. 2005). For instance, in rhesus macaques i.v. THC failed to maintain self-administration across a broad dose range (0.3–10 ug/kg/infusion). In that study, manipulating variables improved THC’s reinforcing effectiveness; THC self-administration was exhibited in 36% of monkeys after daily, non-contingent THC administration, and 50% of monkeys when THC was substituted for cocaine (John et al., 2017). Using the inhaled aerosol route of administration, we also found THC to be a weak reinforcer with less than 50% of the animals responding for any dose above vehicle. However, other cannabinoids were more reliably self-administered compared to THC using this method of administration. As such, modifying the route of administration to inhalation does not seem to enhance THC self-administration, but may support self-administration for other abused CB1 receptor agonists in some monkeys. As was shown previously with THC (John et al., 2017), combining this mode of administration with non-contingent CB1 receptor agonist administration may further their reinforcing effects.

Notable sex differences were observed, the first being that drug deliveries were overall lower among females than males across the drugs tested and for the vehicle. When responding was calculated as a function of vehicle, females exhibited consistent dose-dependent responding for JWH-018; average peak responding for JWH-018 was 50% higher than the vehicle baseline (0.4 ug/kg). This effect that was not apparent in males, for which average responding approximated or was below vehicle. Another notable difference between sexes emerged for THC self-administration. Although responding for THC approximated vehicle in both groups, average responding across THC doses was lower than vehicle in females, whereas average responding across THC doses was above vehicle for males. The observation that females responded for JWH-018 and the lack of responding for THC supports the hypothesis that higher-efficacy CB1 receptor agonists are more reinforcing than partial agonists, like THC. While sex differences in the reinforcing effects of THC have not been elucidated across species, CB1 receptor full agonists are more reinforcing among female rodents compared to males (Fattore et al., 2007, 2009, 2010). Response rates below vehicle baseline may also be related to enhanced negative or aversive effects of THC in females compared to males as have also been observed in rodents (Hempel et al., 2017; Macúchová et al., 2016). The differences in THC self-administration may also be attributed to the accelerated rate of tolerance development to THC’s effects that occur in females relative to males (Wakley et al., 2014). Because the current cohort was exposed to cannabinoids five days a week, the dose response curve for THC self-administration for females may have been shifted to the right of males. This potential shift due to tolerance would have required higher THC doses to be tested in females to detect reinforcing effects.

Limitations:

Given difficulties related to THC administration across species (Justinova et al., 2005), we expected that the JWH compounds, which have a faster onset of action and are shorter acting than THC, would elicit greater responding relative to THC, whereas HU-210’s slow onset of action and long duration of action would make it less reinforcing than the JWH compounds and THC. As described above, relative to alcohol, HU-210 supported the greatest magnitude of responding compared to the other cannabinoids. These unexpected findings may be related to the impact of CB1 receptor agonist pharmacological characteristics (i.e., efficacy, potency, duration of action). However, the magnitude of the inhaled dose is under the control of individuals monkeys, which is a significant limitation that hinders interpretation when conducting any studies of aerosol inhalation. For example, it is possible that different drugs produced different oral sensations that may have affected inhalation behavior. Dose control likely contributed to the variability observed within and between monkeys for vehicle, cannabinoids, and heroin. While puffing behavior required a minimum force to active a pressure sensitive relay, depth of vehicle or drug inhalation was not standardized or measured. In the absence of control over puff volume, inhalation rate, and duration of breath hold it is not possible to deliver precise drug amounts as is done when drugs are delivered intravenously. All the monkeys were experienced “puffers” and they may have titrated their doses to reach a preferred level of intoxication. Thus, potency comparisons are difficult to make using this procedure. These are the same limiting factors encountered when delivering smoked or aerosolized drugs to humans (e.g., nicotine, cannabis).

While new technologies are increasing the ease with which aerosol for inhalation can be generated, conducting inhalation studies is still technically challenging. These challenges are even more difficult when attempting to assess self-administration of aerosols. When aerosol is administered to an animal in an aerosol chamber it can be absorbed through the skin, the nasal mucosa, as well as the lungs making it difficult to identify how much drug was absorbed via each route. Even the technology that limits aerosol exposure to the nose does not guarantee that the drug is absorbed in the lungs as it still must pass nasal mucosa. Although the current procedure involved puffing on a stem for aerosol delivery that most closely models human drug taking and circumvents potential absorption through the skin and nasal passage, it is likely that drug was absorbed both in the lungs and buccally in the mouth. Thus, with all techniques there is variability in the actual route of delivery that is difficult to quantify therefore caution needs to be used when drawing conclusions about drug effects in inhalation studies.

Conclusion:

In summary, inhalation of aerosols produced modest cannabinoid self-administration in non-human primates above vehicle demonstrating that THC and most synthetic cannabinoids tested served as weak reinforcers. Responding was not consistent across animals and sex differences emerged reflecting the inconstant nature of cannabinoid abuse liability in humans. Valuable information was obtained about synthetic cannabinoids from 3 drug classes, with different potencies and agonist efficacies at the CB1 receptor and different durations of action compared to THC using the route of administration most relevant to human use. Procedures to assess the reinforcing effects of aerosolized cannabinoids should be refined to further study the impact of these drugs delivered using an ecologically relevant mode of administration on behavior.

Public Significance Statement:

Cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids are abused in spite of possible adverse health consequences. The current study investigated the reinforcing effects of an ecologically relevant mode of administration (inhalation) of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of cannabis, and three synthetic cannabinoids detected in synthetic cannabinoid products in non-human primates (NHPs). Results point to minimal reinforcing effects of cannabinoids when self-administered by NHPs via aerosol inhalation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grant nos. US National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants DA036809, DA039123, DA027755, and DA047296. We acknowledge and appreciate NIDA for providing the THC and HU-210 for this study, the technical support provided by Jean Willi, and the veterinary care provided by Girma Asfaw.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no competing interests in relation to the work described. In the past three years, ZDC has received research funds and partial salary support from Insys Therapeutics. ZDC has served as a consultant to the following companies: GB Sciences and Beckley Canopy Therapeutics and has served on the scientific advisory board of FSD Pharma.

REFERENCES

- Atwood BK, Huffman J, Straiker A, & Mackie K (2010). JWH018, a common constituent of ‘Spice’ herbal blends, is a potent and efficacious cannabinoid CB 1 receptor agonist: ‘Spice’ contains a potent cannabinoid agonist. British Journal of Pharmacology, 160(3), 585–593. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00582.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood BK, Lee D, Straiker A, Widlanski TS, & Mackie K (2011). CP47,497-C8 and JWH073, commonly found in ‘Spice’ herbal blends, are potent and efficacious CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonists. European Journal of Pharmacology, 659(2–3), 139–145. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auwärter V, Dresen S, Weinmann W, Müller M, Pütz M, & Ferreirós N (2009). ‘Spice’ and other herbal blends: Harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs? Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 44(5), 832–837. 10.1002/jms.1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrus DG, Lefever TW, & Wiley JL (2018). Evaluation of reinforcing and aversive effects of voluntary Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol ingestion in rats. Neuropharmacology, 137, 133–140. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni JP, Barr WH, & Martin BR (1991). Cocaine inhalation in the rat: Pharmacokinetics and cardiovascular response. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 257(1), 307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brents LK, Reichard EE, Zimmerman SM, Moran JH, Fantegrossi WE, & Prather PL (2011). Phase I Hydroxylated Metabolites of the K2 Synthetic Cannabinoid JWH-018 Retain In Vitro and In Vivo Cannabinoid 1 Receptor Affinity and Activity. PLoS ONE, 6(7), e21917. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkey TH, Quock RM, Consroe P, Roeske WR, & Yamamura HI (1997). Delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol is a partial agonist of cannabinoid receptors in mouse brain. European Journal of Pharmacology, 323(2–3), R3–4. 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00146-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneto MS, Gorelick DA, Desrosiers NA, Hartman RL, Pirard S, & Huestis MA (2014). Synthetic cannabinoids: Epidemiology, pharmacodynamics, and clinical implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 144, 12–41. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD (2016). Adverse Effects of Synthetic Cannabinoids: Management of Acute Toxicity and Withdrawal. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(5). 10.1007/s11920-016-0694-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, & Craft RM (2018). Sex-Dependent Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: A Translational Perspective. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 34–51. 10.1038/npp.2017.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, & Haney M (2014). Investigation of sex-dependent effects of cannabis in daily cannabis smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 136, 85–91. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca MA, Bimpisidis Z, Melis M, Marti M, Caboni P, Valentini V, Margiani G, Pintori N, Polis I, Marsicano G, Parsons LH, & Di Chiara G (2015). Stimulation of in vivo dopamine transmission and intravenous self-administration in rats and mice by JWH-018, a Spice cannabinoid. Neuropharmacology, 99, 705–714. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Nasser J, Comer SD, & Foltin RW (2003). Smoked heroin in rhesus monkeys: Effects of heroin extinction and fluid availability on measures of heroin seeking. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 74(3), 723–737. 10.1016/S0091-3057(02)01070-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Spano M, Altea S, Fadda P, & Fratta W (2010). Drug- and cue-induced reinstatement of cannabinoid-seeking behaviour in male and female rats: Influence of ovarian hormones: Sex differences in relapse to cannabinoid-seeking. British Journal of Pharmacology, 160(3), 724–735. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00734.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Spano MS, Altea S, Angius F, Fadda P, & Fratta W (2007). Cannabinoid self-administration in rats: Sex differences and the influence of ovarian function. British Journal of Pharmacology, 152(5), 795–804. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Spano MS, Altea S, Angius F, Fadda P, & Fratta W (2009). Cannabinoid self-administration in rats: Sex differences and the influence of ovarian function: Sex differences in cannabinoid self-administration. British Journal of Pharmacology, 152(5), 795–804. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin R, & Evans S (2001). Location preference related to smoked heroin self-administration by rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology, 155(4), 419–425. 10.1007/s002130100721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, & Fischman MW (1991). Smoked and intravenous cocaine in humans: Acute tolerance, cardiovascular and subjective effects. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 257(1), 247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin Richard W. (2018). Self-administration of methamphetamine aerosol by male and female baboons. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 168, 17–24. 10.1016/j.pbb.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin Richard W., Fischman MW, Nestadt G, Stromberger H, Cornell EE, & Pearlson GD (1990). Demonstration of naturalistic methods for cocaine smoking by human volunteers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 26(2), 145–154. 10.1016/0376-8716(90)90121-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, & Forster MJ (2014). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-like discriminative stimulus effects of compounds commonly found in K2/Spice: Behavioural Pharmacology, 25(8), 750–757. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg BC, Schulze DR, Hruba L, & McMahon LR (2012). JWH-018 and JWH-073: 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-Like Discriminative Stimulus Effects in Monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 340(1), 37–45. 10.1124/jpet.111.187757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel BJ, Wakeford AGP, Nelson KH, Clasen MM, Woloshchuk CJ, & Riley AL (2017). An assessment of sex differences in Δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) taste and place conditioning. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 153, 69–75. 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruba L, Ginsburg BC, & McMahon LR (2012). Apparent Inverse Relationship between Cannabinoid Agonist Efficacy and Tolerance/Cross-Tolerance Produced by Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Treatment in Rhesus Monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 342(3), 843–849. 10.1124/jpet.112.196444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruba L, & McMahon LR (2014). The cannabinoid agonist HU-210: Pseudo-irreversible discriminative stimulus effects in rhesus monkeys. European Journal of Pharmacology, 727, 35–42. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järbe TUC, Deng H, Vadivel SK, & Makriyannis A (2011). Cannabinergic aminoalkylindoles, including AM678=JWH018 found in ‘Spice’, examined using drug (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol) discrimination for rats: Behavioural Pharmacology, 22(5 and 6), 498–507. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328349fbd5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John WS, Martin TJ, & Nader MA (2017). Behavioral Determinants of Cannabinoid Self-Administration in Old World Monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(7), 1522–1530. 10.1038/npp.2017.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Goldberg SR, Heishman SJ, & Tanda G (2005). Self-administration of cannabinoids by experimental animals and human marijuana smokers. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 81(2), 285–299. 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Tanda G, Redhi GH, & Goldberg SR (2003). Self-administration of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by drug naive squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology, 169(2), 135–140. 10.1007/s00213-003-1484-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macúchová E, Ševcíková M, Hrebícková I, Nohejlová K, & Šlamberová R (2016). How various drugs affect anxiety-related behavior in male and female rats prenatally exposed to methamphetamine. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 51(1), 1–11. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DR, & France CP (2020). Interactions between opioids and cannabinoids: Economic demand for opioid/cannabinoid mixtures. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 212, 108043. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshell R, Kearney-Ramos T, Brents LK, Hyatt WS, Tai S, Prather PL, & Fantegrossi WE (2014). In vivo effects of synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073 and phytocannabinoid Δ9-THC in mice: Inhalation versus intraperitoneal injection. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 124, 40–47. 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, & Feigenbaum JJ (1987). 5 Towards cannabinoid drugs. In Progress in Medicinal Chemistry (Vol. 24, pp. 159–207). Elsevier. 10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70422-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Lukas SE, Bree MP, & Mendelson JH (1988). Progressive ratio performance maintained by buprenorphine, heroin and methadone in Macaque monkeys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 21(2), 81–97. 10.1016/0376-8716(88)90053-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y (1999). Pharmacological effects of methamphetamine and other stimulants via inhalation exposure. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 53(2), 111–120. 10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00120-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes M, White WR, McDonald SA, Hill JM, Jeffcoat AR, & Cook CE (1991). Clinical effects of methamphetamine vapor inhalation. Life Sciences, 49(13), 953–959. 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90078-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper WA, & Cole JM (1973). Operant control of smoking in great apes. Behavior Research Methods & Instrumentation, 5(1), 4–6. 10.3758/BF03200111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renner KE (1964). Delay of reinforcement: A historical review. Psychological Bulletin, 61(5), 341–361. 10.1037/h0048335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JS, & McMahon LR (2014). JWH-018 in rhesus monkeys: Differential antagonism of discriminative stimulus, rate-decreasing, and hypothermic effects. European Journal of Pharmacology, 740, 151–159. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiplo S, Asbridge M, Leatherdale ST, & Hammond D (2016). Medical cannabis use in Canada: Vapourization and modes of delivery. Harm Reduction Journal, 13(1), 30. 10.1186/s12954-016-0119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart R, Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, Davenport S, & Midgette G (2017). Variation in cannabis potency and prices in a newly legal market: Evidence from 30 million cannabis sales in Washington state: Legal cannabis potency and price variation. Addiction, 112(12), 2167–2177. 10.1111/add.13886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Munzar P, & Goldberg SR (2000). Self-administration behavior is maintained by the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana in squirrel monkeys. Nature Neuroscience, 3(11), 1073–1074. 10.1038/80577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeford AGP, Wetzell BB, Pomfrey RL, Clasen MM, Taylor WW, Hempel BJ, & Riley AL (2017). The effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) self-administration in male and female Long-Evans rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(4), 242–248. 10.1037/pha0000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakley AA, Wiley JL, & Craft RM (2014). Sex differences in antinociceptive tolerance to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rat. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 143, 22–28. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Lefever TW, Cortes RA, & Marusich JA (2014). Cross-substitution of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and JWH-018 in drug discrimination in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 124, 123–128. 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Ryan WJ, Razdan RK, & Martin BR (1998). Evaluation of cannabimimetic effects of structural analogs of anandamide in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology, 355(2–3), 113–118. 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winger G, Hursh SR, Casey KL, & Woods JH (2002). Relative Reinforcing Strength of Three N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Antagonists with Different Onsets of Action. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 301(2), 690–697. 10.1124/jpet.301.2.690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Goldberg LI, & Ginos JZ (1984). Intravenous self-administration of dopamine receptor agonists by rhesus monkeys. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 230(3), 678–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]