Abstract

Background

Knee instability can arise from various causes and conditions such as neuromuscular disease, central nervous system conditions, and trauma. For people with knee instability, knee orthosis devices are prescribed to help with standing, walking, and performing tasks. We conducted a health technology assessment of stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthoses (SCKAFOs) for people with knee instability, which included an evaluation of the effectiveness, safety, and budget impact of publicly funding SCKAFOs, as well as patient preferences and values.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search of the clinical evidence. We assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS) tool and the quality of the body of evidence according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. We performed a systematic economic literature search and also analyzed the budget impact of publicly funding SCKAFOs in people with knee instabilities in Ontario. We did not conduct a primary economic evaluation as there was limited comparative clinical evidence to inform an economic model. Our reference case budget impact analysis was done from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health; it compared the total costs of a basic mechanical SCKAFO and locked KAFO (LKAFO) for people with knee instability. We also performed scenario analyses varying the following parameters: the price of all classes of SCKAFO (mechanical, electronic, and microprocessor), and the uptake of SCKAFO. To contextualize the potential value of SCKAFO, we spoke with people with knee instability.

Results

We included four studies in the clinical evidence review. We are uncertain if SCKAFOs improve walking ability, energy consumption, or activities of daily living compared with LKAFOs (GRADE: Very low). Our economic evidence review identified one costing analysis that suggested that the costs of orthotic devices such as LKAFOs and SCKAFOs are highly variable according to the cost of materials, professional time, and customization required by the individual patient. The budget impact of publicly funding mechanical SCKAFOs in Ontario over the next 5 years (at a full device cost of $10,784) ranged from an additional $0.50 million in year 1 (at an uptake rate of 30% in the target population [429 eligible people]) to $0.83 million in year 5 (at an uptake rate of 50%), with a total budget impact of $3.34 million over 5 years. We found that the greatest increase in budget impact in the scenario analysis came from the microprocessor SCKAFO device, which had an additional cost of $10.07 million in year 1, increasing to $16.78 million in year 5. When we decreased the cost of a mechanical SCKAFO device (to $7,384), this reduced the 5-year budget impact to $0.89 million (vs. $3.34 million in the reference case). The people with knee instability with whom we spoke reported that they preferred a device that would provide a more typical gait, but starting with this type of device would be easier than switching from an existing LKAFO.

Conclusions

We are uncertain if SCKAFOs improve walking ability, reduce energy consumption, or improve activities of daily living compared with LKAFOs. We estimate that the additional cost to provide public funding for a mechanical SCKAFO in people with knee instability would range from about $0.50 million in year 1 to $0.83 million in year 5, yielding a total budget impact of $3.34 million over 5 years. Depending on the class of SCKAFO and the uptake rate for the device, the budget impact may vary. People who met the criteria for the use of a SCKAFO did have a strong preference for it over an LKAFO.

Objective

This health technology assessment evaluates the effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness of stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthoses for people with knee instability. It also evaluates the budget impact of publicly funding stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthoses and the experiences, preferences, and values of people with knee instability.

Background

Health Condition

Knee instability may occur in any of the three anatomical planes of the knee: sagittal, coronal, and transverse.1 The knee extensors are the muscle groups that have a direct effect on knee stability.2 The knee extensors comprise the quadriceps femoris, tensor fasciae latae, and the knee flexors, which include the hamstring group – sartorius, gracilis, and gastrocnemius. Another mechanism that may contribute to knee instability is overactivity remote from the muscles directly affecting the knee. This can be a secondary cause of improper posture.2 Lack of proprioception (sense of self-movement and body position) can also lead to loss of ability to grade movement or sense movement direction. Lastly, spasticity in the muscles acting around the knee can cause knee instability.

Other conditions or injuries affecting the neural supply to these muscles or the proprioceptive feedback of the knee itself could also result in instability. Other morphological abnormalities or injuries to the osseous, ligamentous, and cartilaginous structures of the knee can also adversely affect knee stability.

Overall, the stability of the knee is reliant on the sound inert structures, as well as on intact nervous and functioning muscular systems, that surround the knee. Any adverse changes to these systems and structures can cause muscle weakness and/or changes in biomechanical functioning, which can lead to pain, falls, and a range of mobility issues.2 People with knee instability may walk with a laboured, unsafe gait that can cause fatigue due to the increased energy demands, as well as injuries to the ankle, hip or back from overuse or misuse of the knee and potentially early osteoarthritis.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Several conditions, including neuromuscular disease (NMD) and central nervous system conditions, can lead to knee instability, which are described below.

Neuromuscular disease describes a heterogenous group of conditions (over 150 types) that primarily affect peripheral nerve, muscle, and/or neuromuscular junction.2 Among the NMDs that can cause knee extensor weakness are motor neuron disease, muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, spinal muscular atrophy, poliomyelitis, myopathies, and inclusion body myositis.3 When defining neuromuscular conditions more broadly, they can encompass upper motor neuron conditions that have a common end point of affecting muscle function. All neuromuscular diseases are considered rare or “orphan” diseases. For example, the age- and sex-adjusted incidence of motor neuron disease (which includes spinal muscular atrophy) in Ontario in 2010/11 was 0.024 per 1,000 persons. The crude prevalence in 2010/11 of motor neuron disease for persons aged 0–17, 18–64, and 65 and older was 0.029, 0.052, and 0.254 per 1,000 persons, respectively.4

Central nervous system conditions can cause weakness and/or spasticity in the muscles around the knee, leading to instability and loss of sensation and proprioception in that limb. Conditions include vascular disorders such as stroke, infections such as polio, and structural disorders such as spinal cord injury and peripheral neuropathy.5 The annual age-adjusted incidence rates in Canada for traumatic spinal cord injury was 42.4 and 51.4 per million for people aged 15–64 and 65 and older, respectively.6 The 2010/11 Canadian Community Health Survey3 estimated that approximately 319,000 people were experiencing the effects of stroke, and 118,000 people were living with spinal cord injury. There are currently no national level data in Canada to estimate the number of individuals living with many neurological conditions (e.g., neuromuscular diseases and central nervous system conditions described above).4 Without these relevant data, it is difficult to provide estimates on the needs of this population.

Trauma, such as peripheral nerve injury, peripheral neuropathy, and femoral nerve trauma, and complications from surgery (including from abdominal, hip, and pelvic surgeries) can also lead to knee instability.

Current Treatment Options

A knee–ankle–foot orthosis device is usually prescribed when an ankle–foot orthosis or knee orthosis is insufficient to adequately control knee instability or when control in more than one plane is required.1 Formerly, locked KAFOs (LKAFOs) were made with bulkier materials, such as metal and leather, but modern LKAFOs are made from lighter materials such as thermoplastics or carbon fibre composites, which fit more closely, potentially affording better control of the limb compared with earlier versions of LKAFOs. The LKAFO is custom-made by an orthotist, with some parts (e.g., the knee joint) coming from a medical equipment manufacturer or through central fabrication (made by a manufacturer). Conventional LKAFOs are currently the standard of care in Ontario and they are listed in the Assistive Devices Program (ADP) manual7 (i.e., they are eligible for public funding).

The prescription of an LKAFO is reliant on a person's clinical presentation rather than their diagnosis. Indications for an LKAFO include knee and/or hip flexion contracture up to 20 degrees, and unilateral or bilateral legs with paralysis. Contraindications include knee and/or hip flexion contracture greater than 20 degrees and non-reducible, moderate to severe spasticity and hip abductor strength less than grade 3 (measured on a 0–5 scale, with 0 representing no muscle contraction and 5 representing typical strength).

Conventional LKAFOs provide the wearer with stability while walking by locking the knee joint in a fully extended position during both stance (standing) and swing (moving the leg forward to step) phases. They can be manually unlocked for sitting. LKAFOs require considerable energy consumption as they encourage an atypical gait pattern, such as circumduction (the movement of the leg in a circular manner), hip swinging, and vaulting during gait.8–10 These difficulties can lead to activity avoidance and early onset osteoarthritis in the lower back, opposite hip, knee, and shoulders in wearers who also require a walker or forearm crutches.

Health Technology Under Review

Stance-control KAFOs (SCKAFOs), also known as stance control orthoses, are a newer generation of KAFO that have been developed to prevent knee flexion during the stance phase and permit free knee motion during the swing phase of the wearer's gait.11 By allowing the knee to bend during the swing phase, the SCKAFO provides a more typical gait pattern than with the conventional LKAFO (current standard of care). Patients can walk with much less effort and reduce compensation from other muscle groups. There are three types of SCKAFO that operate in different ways:

Mechanical devices can work in two ways: a system that uses ankle movement to unlock/release during the swing phase or a pendulum system to activate the mechanism that allows a knee joint to be locked and unlocked at specific moments in the user's gait relative to the positioning/angulation of the leg in gait and stance. These devices require a certain range of motion and/or residual function of the ankle and generally cannot accommodate leg-axis deviations more than 10 degrees (varus/valgus—leg bends in the outward or inward direction), knee flexion contractures, or unstable gait patterns. The device can be made for the user by the manufacturer, or it can be fully custom-made in an orthotic clinic (with some parts, such as knee joints, coming from the manufacturer)

Electronic devices are gait activated. They will unlock/release the knee joint based on the position of the leg during the gait cycle. Position sensor–activated devices are one example, where the orthotic knee is locked for the stance phase and unlocked at the end of the stance, when it reaches a pre-set angle relative to the ground or hip of the wearer.12 These devices do not depend on ankle range of motion function and can accommodate leg axis deviations, knee flexion contractures, and, to a certain extent, unstable gait patterns. These devices are generally made for the user by the manufacturer or fully custom-made in an orthotic clinic (with some parts, such as knee joints, coming from the manufacturer)

Advances in electronic devices have made possible microprocessor devices, which are the most complex of the SCKAFOs. The microprocessor technology unlocks/releases based on information received from electronic sensors 100 times per second. It is designed with a carbon fiber strut with integrated ankle movement sensor and a monocentric (single pivot) microprocessor-controlled knee joint. A knee angle sensor provides feedback on knee angle and knee angle velocity. Extension and flexion damping are adjusted at a frequency of 50 Hz by a microprocessor with the ankle movement, the knee angle, the knee angle velocity, and the temperature of the hydraulic as input signals.12 These devices are fully custom-made by the manufacturer

As stated above, indications and contraindications for the use of SCKAFOs are based on the physical presentation of the patient. Table 1 presents a list of indications and contraindications for the use of SCKAFOs, provided by one manufacturer.13

Table 1:

Indications and Contraindications of Stance-Control Knee–Ankle–Foot Orthoses

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Able to fully stabilize the torso and stand freely | Knee or hip flexion contraction > 10 degrees |

| Muscle strength of hip extensors and flexors must permit the controlled swing-through of the affected leg | Genu varum or valguma > 10 degrees |

| Hip muscle strength or compensatory motion must be possible to advance limb | Bilateral user: hip abductor strength 0–3b |

| Successful evaluation with diagnostic trial tool | Leg length discrepancy ≥ 6 inches (15 cm) Body weight > 275 pounds |

Genu varum is characterized by outward bowing of the knee (bow-legged). Genu valgum is a condition in which the knees angle in and touch each other when the legs are straightened (knock-knee).

Rated on a 0–5 scale, with 0 representing no muscle contraction and 5 representing typical strength.

Additional concerns for the use of SCKAFOs include uncontrolled spasticity, progressive worsening of neurological diseases, patients lacking motivation to increase mobility, and diminished cognition. The inability to release spasticity, especially in knee extensors, would also be a barrier to use. Also important is sufficient hip flexor strength, which is necessary to create the swing phase of gait.

Regulatory Information

Locked knee–ankle–foot orthoses and SCKAFOs are Class I devices14 and therefore do not need Health Canada approval. There are a few manufacturers that produce SCKAFOs that are available in Ontario. Below is a list of manufacturers and SCKAFOs:

Table 2:

Manufacturers and Type of SCKAFO and LKAFO Available in Ontario

| Manufacturer | SCKAFO (Type of Device) | LKAFO |

|---|---|---|

| Ottobock | Free Walk (mechanical) E-MAG Active (electronic) C-Brace (microprocessor) |

These three manufacturers all produce a full line of LKAFO knee joint components. Each manufacturer has two lines of knee joints for LKAFOs with several options within each category: 1. Free motion knee joints include single axis, off set, and polycentric 2. Locking knee joints include drop lock, spring assist locking, ratchet lock, and bale lock |

| Becker | SafetyStride (mechanical) FullStride (mechanical) Stride4 (mechanical) UTX (mechanical) |

|

| Fillauer | Swing Phase Lock II (mechanical) |

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis device; SCKAFO, stance-control KAFO.

Ontario and Canadian Context

Locked knee–ankle–foot orthoses are publicly funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health, through the ADP. This funding pays for 75% of the cost of the device (100% for those with social assistance benefits, such as the Ontario Disability Support Program).15 However, the ADP has maximum list prices for each individual procedure and component code, and approved orthotists are not permitted to bill more than the approved list price. Eligibility for LKAFOs includes long-term physical disability or a physical condition that requires the use of an orthotic device for 6 months or longer to improve function in daily activities. The ADP does not provide funding for prefabricated or centrally fabricated orthoses (i.e., made by the manufacturer), backup devices (i.e., a device that can be used if the primary device stops functioning properly), or SCKAFOs.

We are aware of one province in Canada (Alberta) that publicly funds one SCKAFO (the Free Walk – mechanical, by Ottobock) and two SCKAFO knee joints (the Swing Phase Lock II – mechanical, by Fillauer, and the Horton Stance Phase, which is currently unavailable in Ontario).16 In October 2020, Quebec approved funding for the C-Brace-microprocessor by Ottobock on a case-by-case basis.

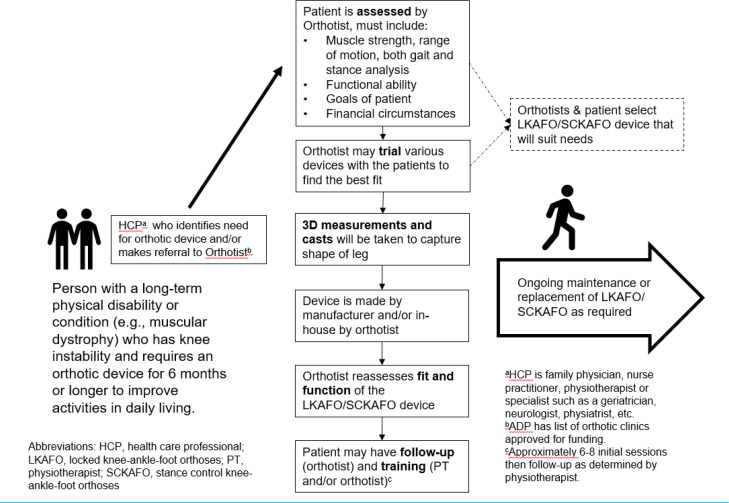

Clinical Pathway

In Ontario, the first stage of the clinical pathway involves the patient presenting with knee instability to their primary health care professional (HCP). If they meet the appropriate criteria (outlined in Figure 1), the HCP will prescribe a knee orthosis and refer the patient to an orthotist. The orthotist uses clinical judgement informed by an evaluation of the patient when choosing the appropriate knee orthosis such as an LKAFO or SCKAFO. Through shared decision-making, including consideration of affordability and ADP funding, the orthotist, patient, and other team members choose the most appropriate device. Once an LKAFO or SCKAFO, if chosen, has been fitted to the patient properly by the orthotist, a referral will be made to a physiotherapist to assist with training in its use. Below is the clinical pathway for a person seeking an LKAFO or SCKAFO.

Figure 1: Clinical Pathway for People with Knee Instability.

Equity

In Ontario, there are two major factors that can impact access to receiving an LKAFO or SCKAFO: socioeconomic status and place of residence (S. Durno, E. Graham, M.Q. Huangfu, A. Lok, A. Moore, M.C. Thiessen, teleconferences, June and July, 2020).

The first factor is that the ADP covers 75% of approved LKAFOs. The other 25% is covered by the patient (if the patient is on the Ontario Disability Support Program, then 100% of the device is covered up to a maximum amount). This coverage alleviates most cost to the patient; however, as described above, the ADP approves only devices or components of a device that do not exceed their set price per individual procedure and component code.7 Many components are more expensive than the set price, and patients may not be able to afford the cost of the entire device or ongoing device maintenance, in addition to the cost of therapy associated with training.

There are other funding sources a patient can access, such as private health insurance, federal government program funding, and provincial worker compensation programs. Access to physiotherapy for assessment of the need for an orthotic device and specialized training in the use of the device would not meet the eligibility criteria for some publicly funded programs. For example, with the Community Physiotherapy Clinic (CPC) program,17 the population included in this review would be excluded because the CPC addresses acute decline, whereas these patients have a chronic condition that requires ongoing maintenance rather than an acute decline, and because they require specialized services that are not widely available within the program. Local hospital-based outpatient programs may be the only publicly funded access points for physiotherapy because they cover patients over 65 years of age.18 Most extended health benefit programs have limited coverage for physiotherapy services for assessment and treatment.

The second factor is that many appointments are necessary to assess the patient's function, fit, as well as function of the device. Training is also needed for a patient to be successful. When a patient lives in a rural or remote community, or away from a city centre, commuting back and forth may not be an option. Barriers can include the cost of specialized transportation if the patient is attending appointments alone, travel time, and loss of work by their caregiver if the patient needs to be accompanied to their appointments.

Access to an LKAFO or SCKAFO may also be impacted by access to referring primary care provider/specialist, access to orthotist and physiotherapist, ability to maintain device, and support to take on and off device by caregiver (depending on the level of impairment of the patient).

Relevant health equity issues contributing to a differential effect of SCKAFOs in people with knee instability across different populations (place of residence and socioeconomic status) will be reported if information is available in the identified studies.

Previous Systematic Reviews

During the scoping phase of this health technology assessment (HTA), we identified several related systematic reviews.1,2 Their research questions were broader than this HTA, in that they evaluated newer LKAFOs compared with older LKAFOs or no comparator. This HTA focuses on evaluating SCKAFO against conventional LKAFOs or no orthoses. They also included other orthotic devices in their reviews (e.g., ankle-foot orthosis and hip knee-ankle-foot orthosis) that were out of scope for this review. The authors of these systematic reviews found that newer LKAFOs (i.e., those made with carbon materials) performed better than older LKAFOs (i.e., those made with metal and leather19). However, they concluded that there was substantial risk of bias in the included studies. They identified a large gap in the evidence on the effectiveness of LKAFOs for managing knee instability.2 The latest systematic review was published in 2017, so rather than using previous systematic reviews to address our research question, we decided to conduct our own literature search to capture any more recent published literature.

Expert Consultation

We engaged with experts in the specialty areas of orthotics and physiatry, and physiotherapists with expertise in neurorehabilitation to help inform our understanding of aspects of the health technology and our methodologies and to contextualize the evidence.

PROSPERO Registration

This health technology assessment has been registered in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42020201805), available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO.

Clinical Evidence

Research Question

What are the clinical effectiveness and safety of stance-control knee-ankle-foot orthoses (SCKAFOs) compared with locked knee-ankle-foot orthoses (LKAFOs) or with no LKAFO in people with knee instability due to different causes and conditions?

Methods

Clinical Literature Search

We performed a clinical literature search on July 21, 2020, to retrieve studies published from database inception until the search date. We used the Ovid interface in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Health Technology Assessment database, and the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED). We used the EBSCOhost interface to search the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

A medical librarian developed the search strategies using controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings) and relevant keywords designed to capture the intervention. We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL and monitored them for the duration of the assessment period (July 2020 to February 2021). We also performed a targeted grey literature search of health technology assessment agency websites as well as clinical trial and systematic review registries. See Appendix 1 for our literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Eligibility Criteria

STUDIES

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published from inception to July 21, 2020

-

Health technology assessments, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies (e.g., before and after, comparative cohort or case-series)

○ Studies must have at least five patients

Exclusion Criteria

Editorials, commentaries, case reports, conferences abstracts, letters

Animal and in vitro studies

PARTICIPANTS

Inclusion Criteria

Adults (≥ 18 years) with knee instability due to different conditions and causes (e.g., neuromuscular disorders, spinal cord injury, etc.)

Exclusion Criteria

Healthy volunteers, children and adolescents (< 18 years)

INTERVENTIONS

Inclusion Criteria

Any type of stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis (e.g., mechanical, electronic, or microprocessor)

Exclusion Criteria

Other orthoses (e.g., hip KAFO, ankle foot orthosis)

COMPARATOR

Inclusion Criteria

Locked KAFO (LKAFO) or no KAFO (i.e., no assistive device)

Exclusion Criteria

Other orthoses (e.g., hip KAFO, ankle foot orthosis)

OUTCOME MEASURES

Condition-specific or generic patient-reported outcomes measuring physical function, level of independence, level of disability, activities of daily living, or quality of life

Pain (self-reported or measured by standardized scales)

Energy consumption and efficiency (measured by changes in pulse rate and oxygen consumption and/or physiological cost index)

Walking ability (e.g., speed of walking measured by velocity, cadence, etc.)

Adverse effects (e.g., falls, tissue damage)

Patient satisfaction

Resource use (e.g., number of follow-up appointments, device malfunctions, access to physiotherapy)

Literature Screening

A single reviewer conducted an initial screening of titles and abstracts using Covidence20 and then obtained the full texts of studies that appeared eligible for review according to the inclusion criteria. A single reviewer then examined the full-text articles and selected studies eligible for inclusion. A single reviewer also examined reference lists and consulted content experts and manufacturers for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on study characteristics and risk-of-bias items using a data form to collect information on the following:

Source (e.g., citation information, study type)

Methods (e.g., study design, study duration and months, reporting of missing data, relevant baseline characteristics [e.g., diagnosis, age, height, weight, body mass index, experience with LKAFOs/SCKAFOs, hip strength, knee strength and ankle strength, equity variables], reporting of outcomes measures used, whether the study compared two or more groups)

Outcomes (e.g., outcomes measured, number of participants for each outcome, number of participants missing for each outcome, outcome definition and source of information, unit of measurement, upper and lower limits [for scales])

Statistical Analysis

We did not undertake any meta-analyses or subgroup analyses because of the small volume of included studies captured in this review, their small sample sizes, and lack of variables reported associated with the subgroup analyses (e.g., equity variables). We undertook a narrative summary of the evidence and presented results in text and tables.

We used WebPlotDigitizer21 to gather point estimates and standard deviations from graphs where available.

Critical Appraisal of Evidence

We assessed risk of bias of non-randomized studies using the Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS)22 (Appendix 2).

We evaluated the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Handbook.23 The body of evidence was assessed based on the following considerations: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The overall rating reflects our certainty in the evidence.

Results

Clinical Literature Search

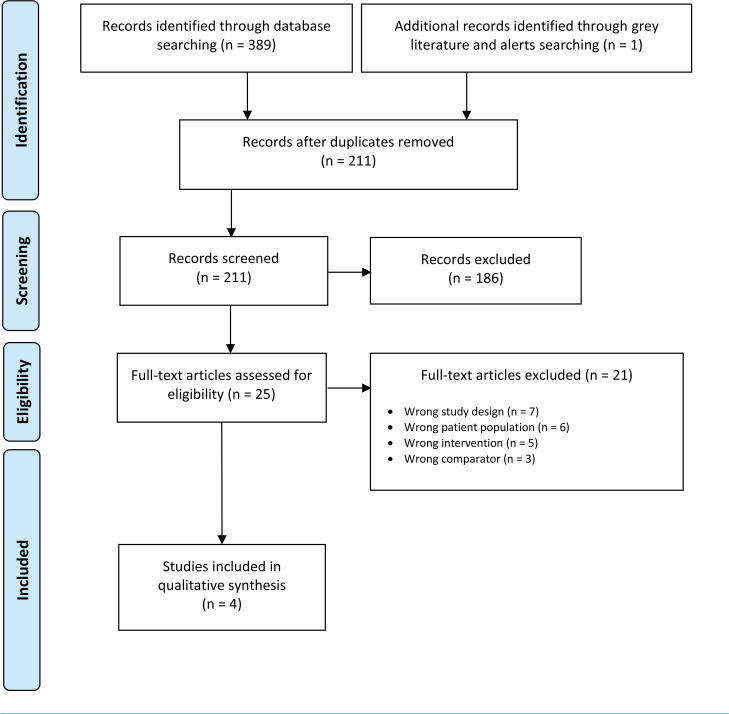

The database search of the clinical literature yielded 389 citations published from database inception to July 21, 2020. We identified one additional study from the search alert. In total, we identified four studies (before and after designs) that met our inclusion criteria. See Appendix 3 for a list of studies excluded after full-text review. Figure 2 presents the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the clinical literature search.

Figure 2: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Clinical Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.24

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Four studies with a before and after design were included.12,25–27 Two studies were conducted in the United States, one in Australia, and one in Germany. The studies were published between 2005 and 2017. Populations included people with various pathologies (e.g., polio, motor neuron disease, inclusion body myositis, incomplete spinal cord injuries, etc.). Previous orthosis experience varied across studies; some people had experience with previous orthoses (e.g., LKAFO, knee brace, posterior offset KAFO), some people had no experience with orthoses, and some used gait aids (e.g., walking sticks, forearm crutches and canes) either in conjunction with orthoses or alone. Where reported, people had between 15 and 28 years of experience with previous orthoses.

Stance-control KAFO (SCKAFO) in the studies included the Dynamic Knee Brace System, Horton Stance Control Knee Joint, SensorWalk, and C-Brace. Two SCKAFOs were mechanical,25,26 one was electronic,27 and one was a microprocessor device.12 Where reported, assessments and fittings took place with orthotists and, in one study, a physiotherapist. Three studies allowed the participants to use the SCKAFO at home for 1–6 months before outcomes were measured and data were collected. The comparator groups were mixed for two studies, so only data comparing SCKAFOs with LKAFOs or no orthoses were collected. The various SCKAFOs were compared to LKAFOs in three studies and no orthoses in one study.

Three studies measured walking ability using metrics such as velocity (cm/sec), cadence (steps/min), and step length (cm). One study measured energy consumption (e.g., oxygen cost, physiological cost index), and one study administered two surveys—one measuring activities of daily living and the other measuring experience with the orthoses. No equity variables were measured in any included studies.

Study and baseline characteristics are reported below in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3:

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author, Year, Country | Sample Size | Inclusion Criteria | Intervention and Comparator | Outcomes of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irby et al, 200527 United States | n = 21 | • Primarily dependent on a KAFO for walking and use an orthosis on a daily basis, or does not use an orthosis, but has a collapsing knee that must be stabilized by a hand on the knee and/or forward trunk lean • May use either one or two KAFOs for ambulation • Must require that the KAFO be locked for community ambulation • Must demonstrate ability to walk a minimum of 100 m (crutches or walker can be used, if needed) • Must have sufficient hip flexor strength to advance the limb |

I: Dynamic Knee Brace System C: Locked KAFO |

• Walking ability |

| Davis et al, 201026 Australia | n = 10 | • Regular use of SCO for at least 4 h each day • Able to safely walk (as determined by the treating clinicians) with the knee in stance control mode and in locked mode during clinical consultations • Able to walk a distance of 200 m with the knee in the stance control and locked mode |

I: Horton Stance Control Knee Joint C: Locked KAFO |

• Energy consumption • Walking ability |

| Bernhardt et al, 201125 United States | n = 9 3 lost to follow-up at 6-mo timepoint |

NR | I: SensorWalk C: No orthosis |

• Walking ability |

| Probsting et al, 201712 Germany |

n = 13 (overall sample) n = 5 (included only patients with locked KAFO comparator) |

• Patients used their previous orthoses for at least 6 mo prior to enrollment in the study | I: C-Brace C: Locked KAFO |

• Activities of daily living • Orthosis Evaluation Questionnaire |

Abbreviations: C, comparator; I, intervention; KAFO, knee–ankle–foot orthosis; NR, not reported; SCO, stance control orthoses.

Table 4:

Baseline Characteristics of Patients From Included Studies

| Author, Year | Age (SD) | Height, Weight, and BMI (SD) | Diagnosis | Previous Orthoses, Walking Aids, and Lived Experience | Hip, Knee, and Ankle Strengtha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irby et al, 200527 | 53 yr (± 15) Range: 11–76 yr |

Height: NR Weight: 84 kg (± 20) Range: 51–127 kg BMI: 29 ± 6 Range: 19–40 |

Poliomyelitis = 12 Other pathologies or trauma (includes neuropathies, incomplete spinal cord injuries, spina bifida, multiple sclerosis, and muscular dystrophy) = 9 |

Locked KAFO = 13 No assistive = 8 Experience: 28 ± 18 yr Range: 19–40 yr |

Hip extensor: 2.1 Range: 0–4.5 Hip flexor: 2.7 Range: 0–4 Knee extensor: 1.8 Range: 0–5 Knee flexor: NR Ankle dorsiflexion: 2.1 Range 0–5 Ankle plantarflexion: NR |

| Davis et al, 201026 | 61.9 yr Range: 51–72 yr |

Heigh: 163 cm Range 151–182 cm Weight: 71.7 kg Range: 56–111 kg BMI: NR |

Poliomyelitis = 9 Motor neuron disease = 1 |

None = 3 Solid GRAFO = 4 Locked KAFO = 1 Knee brace = 1 Posterior offset KAFO = 1 Walking aidsb: Walking stick = 2 Two walking sticks = 2 Forearm crutch = 1 Two forearm crutches = 1 Experience: 15 yr Range: 0–60 yr |

No average estimates reported |

| Bernhardt et al, 201125 | 60 yr (± 9) | Height: NR Weight: NR BMI: 26.6 (± 4.5) |

All patients had inclusion body myositis | Cane = 4 Experience = None |

NR |

| Probsting et al, 201712 | 54.4 yr | Height: NR Weight: NR BMI: NR |

Poliomyelitis = 4 Incomplete spinal cord injury = 1 |

Locked KAFO = 5 Experience: NR |

No average estimates reported |

Abbreviations: KAFO, knee–ankle–foot orthosis; GRAFO, ground reaction ankle foot orthosis; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation.

Walking aids were used in conjunction with KAFOs.

Scale from 0–5, with 0 representing no muscle contraction and 5 representing typical strength.

Risk of Bias in the Included Studies

All studies were before and after designs, which means that outcome measurements were taken in the same group of people. Measurements were first taken when the person was using the comparator (i.e., LKAFO or no orthosis), and then measurements were taken when the person was the using SCKAFO. For all included studies, authors did not report the timeframe of when people were recruited or when data were collected on participants. All studies were small, ranging from 5 to 21 participants. Learning effect seemed to be accounted for as one study divided the analysis into “novice” and “experienced” users and the other three studies allowed patients to use the SCKAFO at home before collecting outcome data. Certified orthotists took measurements around patients’ presentation and strength using standardized tools. The orthotists also collected outcome data and both orthotists and participants were not blinded due to the before and after design of the studies. Loss to follow-up was only reported in two of the four studies. Three of four studies had poor reporting, where outcome estimates were only presented in graphs and only partial information on baseline characteristics were reported and details of orthotist assessments were not provided.

Walking Ability

Three of four studies measured outcomes associated with walking ability, including velocity (the speed at which the person walks), cadence (steps per minute), stride length (the size of each step), and swing time (how long it takes to take a step).25–27

One study did not provide estimates in the text,27 so we extracted data from graphs using WebPlotDigitizer.21 Another study did not provide average estimates in the text and graphs, so we reported the outcomes as written in the text of the article.25 Lastly, one study found that three of four outcomes (velocity, cadence, and swing time) favoured the SCKAFO.26 Stride length was shorter in the LKAFO group.

Irby et al27 divided their participants into “experienced” and “novice” groups based on previous device use. The experienced group routinely used an LKAFO for ambulation. The novice group did not use an LKAFO. The authors found that novice users showed significant changes between the LKAFO and SCKAFO conditions for three of the measures (velocity, cadence, and stride length). Velocity increased from 55.3 to 59.0 cm/s (P = s.034). Cadence increased from 76.8 to 84.9 steps/min (P = 0.042). Stride length increased from 86.3 to 99.2 cm (P = .072). Experienced users tended to reduce velocity and cadence during early SCKAFO testing, but this was not significant (P = .10). On aggregate, there were no significant changes between the LKAFO and SCKAFO conditions (see Table 5). The authors hypothesized that experienced LKAFO users had ingrained gait patterns designed to compensate for walking with a standard LKAFO. These patterns may have limited the ability of those users from taking full and immediate advantage of the SCKAFO capabilities.

Table 5:

Outcomes Associated With Walking Ability

| Velocity in cm/s (± SD) | Cadence in steps/min (± SD) | Stride Length in cm (± SD) | Swing Time in sec (± SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | Sample Size | SCKAFO | LKAFO | SCKAFO | LKAFO | SCKAFO | LKAFO | SCKAFO | LKAFO |

| Irby et al, 200527,a,b | n = 21 | 63.5 (4.5) | 62.5 (4.2) | 75.6 (3.4) | 76.4 (2.1) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Davis et al, 201026 | n = 10 | 72.9 (25.7) | 65.0 (24.5)c P = .000107 |

78.9 (17.6) | 73.9 (18.2)c P = .000016 |

55.0 (11.9) | 53.6 (12.0)d | 0.56 (0.10) | 0.64 (0.10)c P = .00067 |

| Bernhardt et al, 201125,e | n = 6 | People walked slower with the SCKAFOf P = .025 |

People walked with a lower cadence with the SCKAFOf P = .007 |

People had a shorter stride length with SCKAFO | NR | NR | |||

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis device; NR, not reported; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis; SD, standard deviation.

These estimates were extracted using WebPlotDigitizer21 for novice and experienced users combined.

Irby et al27 reports standard error, not standard deviation.

This comparison was statistically significantly in favour of SCKAFO.

Stride length in the affected leg.

Poor reporting of data as results were provided by the authors in the text only. Graphs were presented; however, there were no average estimates.

This comparison was statistically significant (in favour of no orthosis).

The quality of the evidence for outcomes associated with walking ability was very low (see Appendix 2, Table A2) and was downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision.

Activities of Daily Living

One study evaluated activities of daily living, comparing SCKAFO with LKAFO.12 There were 45 items on the Activities of Daily Living questionnaire and the scale ranged from 1 to 6, where 1 = very difficult and 6 = very easy. Table 6 shows the items where there was a significant difference between the two groups (in favour of SCKAFO). No items favoured the LKAFO group. Based on the very small sample size (n = 5), there were items that approached significance. These included walking on uneven terrain (P = .07), pushing or pulling a shopping trolley (P = .07), loading or unloading the trunk of a car (P = .07), carrying a heavy object (P = .07), walking with different shoes (P = .07), walking up stairs (P = .07), getting into public transportation (P = .07), and standing for a longer period of time (P = .07).

Table 6:

Activities of Daily Living

| Mean Ratings | ||

|---|---|---|

| Items | SCKAFO (± SD) | LKAFO (± SD)a |

| Family and Social Life | ||

| Going for a walk | 5.0 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.4) |

| Mobility and Transportation | ||

| Stepping on a sidewalk curb | 5.0 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.1) |

| Stepping over minor obstacles | 4.8 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.6) |

| Stepping on minor obstacles like rocks | 4.8 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.7) |

| Walking down stairs | 5.4 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.1) |

| Walking up ramps | 5.2 (0.8) | 2.4 (1.1) |

| Walking on unknown terrain | 4.6 (1.1) | 2.2 (0 (0.8) |

| Walking outside in bad weather | 4.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) |

| Standing in a crowded bus | 4.4 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.4) |

| Other Activities | ||

| Sitting for a longer period of time | 5.0 (1.4) | 2.6 (0.5) |

| Sitting on a low chair or sofa | 4.8 (1.1) | 2.4 (0.5) |

| Doing something else while walking | 4.4 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.7) |

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis device; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis device; SD, standard deviation.

This comparison was statistically significant (in favour of SCKAFO).

The quality of the evidence for activities of daily living was very low (see Appendix 2, Table A2) and was downgraded for imprecision.

Energy Consumption

One study measured outcomes associated with energy consumption.26 These outcomes measured the following: oxygen cost (calculated by dividing net oxygen consumption by the distance walked in metres per minute) and physiological cost index (calculated as the ratio of heart rate difference [exercise – rest] to walking velocity in metres per minute). This study found no difference in the oxygen cost of walking or the physiological cost index, concluding that SCKAFO did not decrease energy consumption during walking compared to LKAFO.

The quality of the evidence for outcomes associated with energy consumption was very low (see Appendix 2, Table A2) and was downgraded for imprecision.

Table 7:

Outcomes Associated With Energy Consumption

| Author, Year | Sample Size | Oxygen Cost (ml/kg/min) (± SD) | Physiological Cost Index (beats/meter/min) (± SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCKAFO | LKAFO | SCKAFO | LKAFO | ||

| Davis et al, 201026,a | n = 10 | 0.224 (0.069) | 0.213 (0.081) | 0.70 (0.34) | 0.65 (0.32) |

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis device; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis device.

No comparisons were statistically significant.

Patient Satisfaction and Risk of Falls

One study provided only a narrative summary of data collected on patient satisfaction and risk of falls through a non-validated questionnaire. In terms of patient satisfaction, the authors stated that “all participants had complaints about the size, bulk, cosmesis, and noise of the SCKAFO, as well as difficulty donning and doffing the brace.”25 However, it is worth noting that this group did not have an orthosis prior to the study. Considering falls, the authors stated that “some participants felt the SCKAFO was helpful in safeguarding against falls and providing stability.” The quality of the evidence was not assessed for this outcome because outcomes were only described in text.

Other Outcomes

We did not find any data from the included studies on the following pre-specified outcomes:

Pain (self-reported or measured by standardized scales)

Adverse effects (e.g., falls, tissue damage)

Resource use (e.g., number of follow-up appointments, device malfunction, access to physiotherapy)

Discussion

Walking ability was measured in three of the four studies. While it is important to describe the technical measures (e.g., velocity, cadence, oxygen cost, etc.) of the effectiveness of wearing a SCKAFO or LKAFO, these measures do not speak directly to the utility of the devices. Technical measures only assess if a person's walking ability resembles a more typical gait pattern. However, while wearers are unlikely to achieve a completely typical gait pattern, they may see an increase in ease of movement. Therefore, patient-reported outcomes are important to understand the utility of the device. Only one study examined activities of daily living and the authors found that many tasks were significantly easier using a SCKAFO compared with an LKAFO. One study found that “novice” users had better walking ability with SCKAFO compared with LKAFO.27

The included studies are of low quality for various reasons. Studies included in this review had small sample sizes due to the rarity of the conditions (e.g., motor neuron disease), which makes it difficult to recruit a large number of people into a study. However, the studies also suffered from a high risk of bias due to poor study design (e.g., unclear if the samples were representative, no independent outcome assessments, unclear follow-up) and poor reporting. Also, people who are prescribed orthotic devices need training with the device. While some studies allowed people to bring the device home for 1 to 6 months before collecting data, there were no details of proper training with an orthotist or physiotherapist. Previous reviews that are broader in scope and include both comparative and non-comparative studies also reported that the evidence overall is of low quality.1,2,9 It is unlikely that higher quality evidence will be published examining the effects of LKAFO and SCKAFO on outcomes of interest.

Conclusions

We are uncertain if SCKAFOs improve walking ability, energy consumption, or activities of daily living (GRADE: Very low) compared with LKAFOs.

Economic Evidence

Research Question

What is the cost-effectiveness of stance-control knee-ankle-foot orthoses (SCKAFOs) compared with locked knee-ankle-foot orthoses (LKAFO) or with no LKAFO in people with knee instability due to different causes and conditions?

Methods

Economic Literature Search

We performed an economic literature search on July 22, 2020, to retrieve studies published from database inception until the search date. To retrieve relevant studies, we developed a search using the clinical search strategy with an economic and costing filter applied.

We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL, and monitored them for the duration of the assessment period. We also performed a targeted grey literature search of health technology assessment agency websites, clinical trial and systematic review registries, and the Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry. See the Clinical Literature Search section, above, for further details on methods used. See Appendix 1 for our literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Eligibility Criteria

STUDIES

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published from inception to July 22, 2020, and studies identified through database auto-alerts

Studies comparing SCKAFO with LKAFO in people with knee instability due to different causes and conditions

Cost-utility, cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit, cost-consequence, or cost analyses

Exclusion Criteria

None

POPULATION

Inclusion Criteria

Adults (≥ 18 years years) with knee instability due to different causes and conditions

Exclusion Criteria

Healthy volunteers, children (< 18 years)

INTERVENTIONS

Inclusion Criteria

Any type of SCKAFO (e.g., mechanical, electronic, or microprocessor)

Exclusion Criteria

Other KAFO device (e.g., hip KAFO, ankle foot orthosis)

COMPARATOR

Inclusion Criteria

LKAFO or no LKAFO (i.e., no assistive device)

Exclusion Criteria

Other orthosis (e.g., hip KAFO, ankle–foot orthosis)

Outcome Measures

Costs

Health outcomes (e.g., quality-adjusted life-years, adverse events avoided)

Incremental cost

Incremental effectiveness

Cost per incremental quality-adjusted life-year gained

Literature Screening

A single reviewer conducted an initial screening of titles and abstracts using Covidence20 and then obtained the full texts of studies that appeared eligible for review according to the inclusion criteria. A single reviewer then examined the full-text articles and selected studies eligible for inclusion.

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on study characteristics and outcomes to collect information about the following:

Source (e.g., citation information, study type)

Methods (e.g., study design, analytic technique, perspective, time horizon, population, intervention[s], comparator[s])

Outcomes (e.g., health outcomes, costs, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios)

Study Applicability and Limitations

We determined the usefulness of each identified study for decision-making by applying a modified quality appraisal checklist for economic evaluations originally developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom to inform the development of NICE's clinical guidelines.16 We modified the wording of the questions to remove references to guidelines and to make it specific to Ontario. Next, we assessed the applicability of each study to the research question (directly, partially, or not applicable).

Results

Economic Literature Search

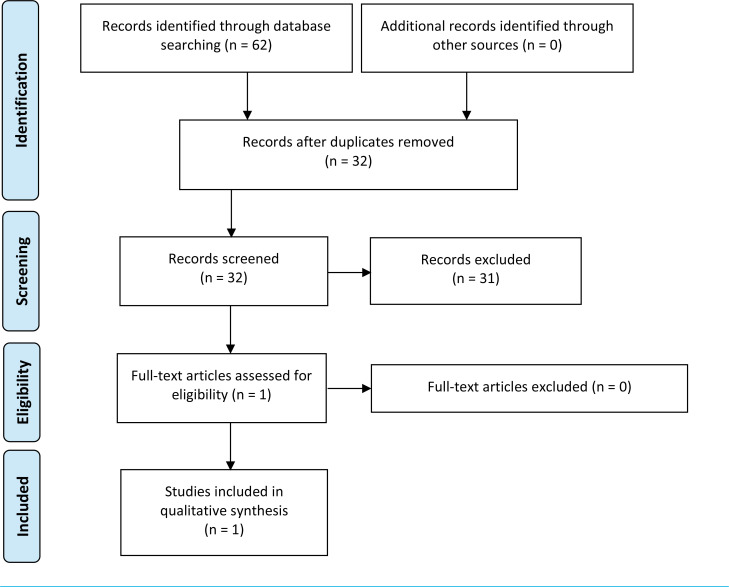

The database search of the economic literature yielded 62 citations published from database inception until July 22, 2020. We did not identify any additional studies from other sources. In total, we identified 32 studies after removing duplicates that met our inclusion criteria. Figure 3 presents the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the economic literature search.

Figure 3: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Economic Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al, 2009.24

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

Overview of Included Economic Studies

We identified one costing analysis2 that met the inclusion criteria. The characteristics and results of the included study is summarized in Table 8.

Table 8:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Summary

| Author, Year, Country of Publication | Analytic Technique, Study Design, Perspective, Time Horizon | Population | Intervention and Comparator | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| O'Connor et al, 2016,2 United Kingdom | Costing analysis (cross-sectional survey) National Health Service (payer's perspective) NA |

Adult patients with NMD or CNS disorders | Intervention: LKAFO and SCKAFO Comparator: No comparator reported |

NA | Undiscounted, United Kingdom (2015 GBP)a LKAFO: Range: £73 to £3,553 Mean: £484 – £3,144 (depending on the type of KAFO device) SCKAFO: Range: £2,251 to £3,240 Mean: £2,831 |

NA |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system disorders; LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis; NA, not applicable; NMD, neuromuscular disorders; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis.

The year of the costing survey.

The analysis was included in a health technology assessment conducted by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom.2 The study population included patients with neuromuscular and central nervous system disorders. Clinical outcomes reported in the health technology assessment were limited and were not included in the costing analysis. The authors conducted a costing survey for health care professionals, such as orthotists, to help estimate the cost of various off-the-shelf or custom-made orthotic devices such as a standard conventional, cosmetic, or carbon fibre LKAFO and a SCKAFO. There was no indication of the type of SCKAFO included in the costing analysis. Cost components considered in this analysis included materials and staffing costs. Unit costs from the National Health Service (NHS) were also considered for prefabricated (off-the-shelf) LKAFO devices. Three scenarios—low, average, and high cost—were analysed to account for the variability in time, staffing, and material costs. Costs (expressed in 2015 GBP) were not reported to be discounted or inflated, and the analysis was conducted from the payer perspective (the NHS).

O'Connor et al2 noted that the cost of an individual LKAFO could be highly variable, ranging from £73 to £3,553 (average: £484 to £3,144, depending on the type of LKAFO), and the cost of a SCKAFO ranged from £2,251 to £3,240 (average: £2,831). An off-the-shelf LKAFO was estimated to cost between £73 and £1,898, and the price for a custom-made LKAFO could range from £2,198 to £3,553. The difference between these cost estimates was attributed to device type and the labour involved in customizing an LKAFO. The largest cost component of a standard (conventional) LKAFO product was for labour (i.e., £2,009 to £2,998 of the £2,220 to £3,189 total cost of an LKAFO), whereas the main cost component for a standard carbon fibre LKAFO and an off the shelf LKAFO was the price of the device (i.e., £2,500 of the £2,564 to £3,553 total cost for a custom cosmetic LKAFO and £900 of the total cost of an off-the-shelf LKAFO). Similarly, the largest cost component of the SCKAFO was the price of the device (£2,187 of the £2,251 to £3,240 total cost of a SCKAFO).

Applicability of the Included Studies

Appendix 5 provides the results of the quality appraisal checklist for economic evaluations applied to the included studies. One study was deemed partially applicable to the research question. None of the studies were conducted from a Canadian perspective.

Discussion

Our literature review showed that the economic evidence of SCKAFO for people with knee instabilities is very limited. Only one study, O'Connor et al,2 met our inclusion criteria; however, the authors did not conduct an economic evaluation or budget impact analysis as a comparison between the two types of the device (e.g., SCKAFO vs. LKAFO). In addition, this analysis was not directly applicable to the Ontario context.

Some other notable strengths of the analysis include multiple costing sources, such as the NHS Supply Chain unit costs compared with expert opinion for off-the-shelf devices.2 The study also conducted lower, average, and upper bound scenarios for all analyses. These methods revealed a large variation in the cost of LKAFOs and SCKAFOs. While material and staffing costs were reported, the analysis did not consider all cost components. For instance, orthotists who participated in the costing survey could not give a clear indication of the cost for lifetime use of the device, or the cost of replacement, if needed. Lastly, it was unclear whether the costs reported for these devices would be partially or fully covered from a payer's perspective. These limitations demonstrate the complexity of costing orthoses used for knee instability, as many of the devices are custom-made.

Conclusions

We identified no studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of SCKAFOs compared with LKAFOs in people with knee instability. Thus, the cost-effectiveness of using SCKAFOs compared with LKAFOs in Ontario and elsewhere is unknown.

Primary Economic Evaluation

Our analysis sought to understand the economic and clinical outcomes of SCKAFOs compared with LKAFOs in people with knee instabilities. However, there is limited comparative clinical evidence to inform an economic model. While there was some evidence available, we are uncertain if SCKAFOs improve walking ability, energy consumption, or activities of daily living (GRADE: Very low) compared with LKAFOs (see our clinical review, above). The limited and very low quality of evidence on health outcomes that could be used in a cost-effectiveness or cost–utility analysis meant that the clinical evidence did not support economic modelling. To our knowledge, there are no previous economic models evaluating LKAFOs or SCKAFOs. As such, we did not conduct a primary economic evaluation, and we focused on a standalone budget impact analysis for publicly funding SCKAFOs (mechanical, electronic, or microprocessor) in people with knee instability due to different causes and conditions.

Budget Impact Analysis

Research Question

What is the potential 5-year budget impact for the Ontario Ministry of Health of publicly funding stance-control-knee-orthoses (SCKAFOs) for people with knee instability due to different causes and conditions?

Methods

Analytic Framework

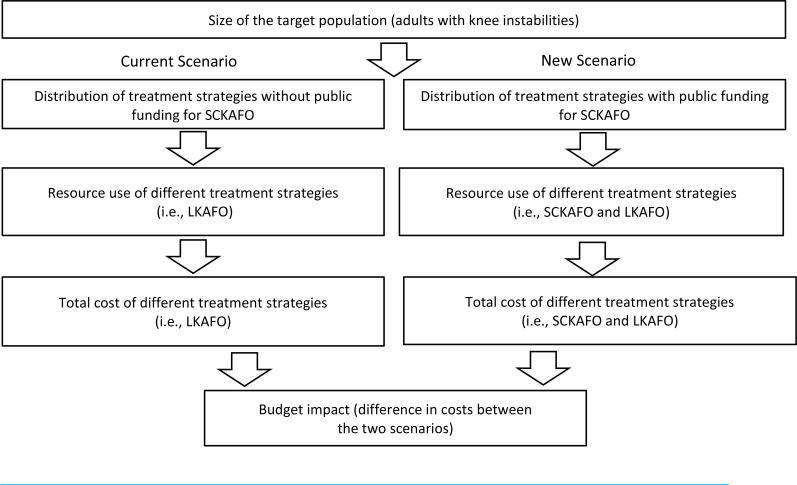

We estimated the budget impact of publicly funding SCKAFO devices using the cost difference between two scenarios: (1) current clinical practice without public funding for SCKAFO devices (the current scenario) and (2) anticipated clinical practice with public funding for SCKAFO devices (the new scenario, where there is a mix of SCKAFO and LKAFO). Figure 4 presents the budget impact model schematic.

Figure 4: Schematic Model of Budget Impact.

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis.

We conducted a reference case analysis and sensitivity analyses. Our reference case analysis represents the analysis with the most likely set of input parameters and model assumptions. Our sensitivity analyses will explore how the results are affected by varying input parameters and model assumptions.

Key Assumptions

The target population remains constant over the next 5 years and represents people with an LKAFO (i.e., no gradual uptake of LKAFO), as the number of people requesting these devices in Ontario was constant over the last 5 years

People currently receiving a standard LKAFO are eligible to receive a SCKAFO, and 30% to 50% of people eligible for an LKAFO switch to a SCKAFO over a 5-year period

The mix of populations with different types of SCKAFO devices is unavailable (no data on the proportion of people with a mechanical, electronic, or microprocessor SCKAFO)

The total price estimated for SCKAFOs represents a conservative (maximum) cost estimate for a mechanical SCKAFO

Cost estimates for SCKAFO devices were based on current hourly wages for personnel, materials, and follow-up costs

The cost of follow-up appointments for both devices were included in the Assistive Devices Program (ADP) codes and price estimates used in the reference case and scenario analyses

People who might require a device replacement were included in our target population

The same proportional coverage for funding LKAFO devices is applicable to SCKAFO devices

Target Population

The target population for this analysis included adults (≥ 18 years) with knee instabilities due to different causes and conditions (e.g., neuromuscular disorders, spinal cord injury, etc.), who received an LKAFO in Ontario. To estimate the size of the target population, we first obtained the number of people in Ontario requesting LKAFO devices from the ADP. Based on 2018/2019 fiscal year data, we assumed 429 people have requested devices for LKAFOs, and all of them received funding (ADP, personal communication, May 2020). We did not break down the total population by disease-type or pathology, as subgroups are likely to be small in size and the underlying condition is of limited utility in informing treatment decisions. We assumed that the number of people receiving an LKAFO is constant each year, and that the target population would represent people requiring a new LKAFO, and some receiving a replacement device. More specifically, a person might need a replacement once every 2 to 5 years. Assuming no change in the number of LKAFO requests (i.e., 429) per year, the number of people requiring a replacement is captured in our target population estimate (which reflected incident and some prevalent use of LKAFOs; ADP, personal communication, December 2020). This assumption regarding the estimated target population is consistent with the annual number of referrals received by clinical experts (approximately 400 per year; Ontario Association of Prosthetics and Orthotics [OAPO] Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, January 2021). We also assumed that a gradual uptake of 30% to 50% of people with an LKAFO would be eligible for a SCKAFO (incremental uptake assumed to be 5% per year, starting with 30% in year 1 and reaching 50% in year 5). The remainder would continue to use an LKAFO (OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, September 2020). For our new scenario, the total number of people using an LKAFO or a SCKAFO was 1,287 and 858, respectively, over the next 5 years. Our approach related to estimating the target population is summarized in Table 9.

Table 9:

Target Population: Number of People With Knee Instabilities Expected to Receive a SCKAFO or an LKAFO in Ontario

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population/volume of LKAFOsa | 429 | 429 | 429 | 429 | 429 | 2,145 |

| LKAFO volume replaced by SCKAFOs | 30% | 35% | 40% | 45% | 50% | — |

| LKAFO | 300 | 279 | 257 | 236 | 215 | 1,287 |

| SCKAFO | 129 | 150 | 172 | 193 | 214 | 858 |

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot-orthosis; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot-orthosis.

Data provided by Assistive Devices Program, Personal Communication, May 2020.

Current Intervention Mix

Eligibility for LKAFO devices includes long-term physical disability or a physical condition that requires the use of an orthotic device for 6 months or longer to improve function in daily activities. The ADP typically reimburses 75% of the cost of a prescribed LKAFO device for the majority of eligible people and 100% for those receiving social assistance benefits, to a maximum amount based on the benefits available for the components and procedures of the device that is recommended and approved. Thirty-six percent of people with an LKAFO received 100% funding in the 2018/2019 fiscal year (ADP, personal communication, December 2020). Therefore, in our reference case analysis, we assumed 36% of people received 100% funding from the ADP and the remainder (64%) received 75% funding, as indicated in the administration manual.28 The ADP also cites maximum list prices for device components and services; approved orthotists cannot bill more than the approved list price.

The ADP does not provide funding for SCKAFO devices (ADP, personal communication, 2020). Therefore, we assumed that SCKAFO devices are not funded for knee instability in our current scenario, and that all people receive an LKAFO device.

Uptake of the New Intervention and New Intervention Mix

In our new scenario, in which SCKAFO devices are publicly funded for people with knee instabilities, we assumed that some people would receive a SCKAFO instead of an LKAFO device. Similar to the current scenario, we also assumed that 36% of all people with a SCKAFO device would receive full coverage, and the remainder would receive 75% coverage to a maximum amount provided by the ADP program (ADP, personal communication, December 2020). Based on expert consultations, we assumed that not all people who would have received an LKAFO under the current scenario would receive a SCKAFO under the new scenario (OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, September 2020). We assumed that 30% to 50% people would opt for a SCKAFO over an LKAFO (see Table 10; OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, September 2020).

Table 10:

Uptake of People Expected to Receive Full (100%) or Partial (75%) Funding for a SCKAFO or an LKAFO in Ontario

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Totala | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population/volume of people using LKAFOsb | 429 | 429 | 429 | 429 | 429 | 2,145 |

| LKAFO volume replaced by SCKAFOs | 30% | 35% | 40% | 45% | 50% | — |

| LKAFO | 300 | 279 | 257 | 236 | 215 | 1,287 |

| Full coverage (36% of people) b |

108 | 100 | 93 | 85 | 77 | 463 |

| 75% coverage (64% of people) |

192 | 178 | 165 | 151 | 137 | 823 |

| SCKAFO | 129 | 150 | 172 | 193 | 214 | 858 |

| Full coverage (36% of people)c |

46 | 54 | 62 | 69 | 77 | 308 |

| 75% coverage (64% of people)c |

82 | 96 | 110 | 124 | 137 | 549 |

Abbreviations: LKAFO, locked knee-ankle-foot-orthosis; SCKAFO, stance-control knee-ankle-foot-orthosis.

Numbers may be inexact due to rounding.

Data provided by the Assistive Devices Program, personal communications, May and December 2020.

Assumed the same proportions would be applicable to SCKAFO users.

Resources and Costs

Conventional LKAFOs are currently the standard of care in Ontario. They are eligible for public funding and listed in the ADP product manual.7 Our main source of pricing information was provided by orthotists, as suggested by manufacturers and experts, who have experience setting a price to a standard LKAFO using the ADP product manual. This pricing information includes codes for:

Materials

Device components

Professional orthotist time

The ADP does not cover warranty costs for LKAFO devices,28 but extended warranties may be provided by the vendor or purchased out-of-pocket by the individual patient.28 Our overall budget impact estimate includes repair and maintenance costs that are not covered by any warranties that might exist. We also did not include costs of adverse events due to a lack of comparative data on adverse events (see clinical review). A rework factor was already included in ADP codes, which covered all possible errors that can occur such as measurement, cast modification, manufacturing, alignment of joints, materials modifications, knee and ankle joint modifications and more (OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, October 2020).

LKAFOS

The price of LKAFO and SCKAFO devices can vary greatly. This is mainly due to the cost of customizing the LKAFO device for the individual patient (OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, September 2020). In consultation with orthotists, we developed a costing strategy to account for the variation in price estimates. We first engaged with experts to obtain commonly used ADP codes to estimate an average price for a standard LKAFO (e.g., $6,151.00 for 100% coverage or $4,613.25 for 75% coverage). We then applied the proportion of people who received 100% and 75% coverage (36% and 64% of people, respectively) to our cost estimates (we based our estimate on the proportion provided by the ADP). We used this estimate in our reference case analysis and assumed it represented the common cost of an LKAFO device. Table 11 outlines the unit cost per component, total cost of KAFOs, and the cost funded by the ADP.

Table 11:

Reference Case Analysis: Price Estimates for a Standard LKAFO

| KAFOa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Assessment/Materials/Device Component | Quantity | Unit Price | Total Price | ADP Funding (75%) |

| Tracing/cast/fit—thermoplastic AFO (CNLCF1002) | 1 | 498.00 | 498.00 | 373.50 |

| KAFO—thermoplastic (CNLCF2002) | 1 | 619.00 | 619.00 | 464.25 |

| Thermoplastic hinged AFO (CNLCF1250)b | 1 | 395.00 | 395.00 | 296.25 |

| Thermoplastic thigh cuff (CNLCF2070) | 1 | 236.00 | 236.00 | 177.00 |

| Pad (each) (CNLCF0010) | 8 | 16.00 | 128.00 | 96.00 |

| Pad cover (CNLCF0040) | 8 | 34.00 | 272.00 | 204.00 |

| Installation of uniplanar ankle joints (CNLCF1070) | 2 | 93.00 | 186.00 | 139.50 |

| Reinforced strap (CNLCF0100) | 5 | 42.00 | 210.00 | 157.50 |

| Joint head bending upright (CNLCF1100) | 6 | 82.00 | 492.00 | 369.00 |

| Molded patella cap (CNLCF2190) | 1 | 177.00 | 177.00 | 132.75 |

| Align and install knee joints (CNLCF2010) | 2 | 147.00 | 294.00 | 220.50 |

| External posting to AFO (CNLCF1820) | 1 | 42.00 | 42.00 | 31.50 |

| Multi-layer custom foot bed (CNLCF1730) | 1 | 142.00 | 142.00 | 106.50 |

| Installation of bale lock (CNLCF2040) | 2 | 69.00 | 138.00 | 103.50 |

| Installation of NYU stirrups (CNLCF1071)c | 2 | 152.00 | 304.00 | 228.00 |

| Component Costs | ||||

| Ankle joints (CNLCF3300) | 2 | 137.00 | 274.00 | 205.50 |

| Knee-joint locking (CNLCF3323) | 2 | 393.00 | 786.00 | 589.50 |

| Uprights (lower extremity) (CNLCF3310) | 6 | 142.00 | 852.00 | 639.00 |

| Stirrups (stirrups thermoplastic) (CNLCF3405)c | 2 | 53.00 | 106.00 | 79.50 |

| Total cost of device and time required | 6,151.00d | 4,613.25 | ||

Abbreviations: ADP, assisted devices program; AFO, ankle–foot–orthoses; KAFO, knee AFO.

Source: Ontario Association of Prosthetics and Orthotics, September 2020, Assistive Devices Product Manual.

All costs in 2020 CAD.

Hinged AFO controls and limits subtalar joint motion and allows for free ankle motion.

Stirrups are metal connecting thermoplastic foot shell to ankle joints.

Cost of device for people who have 100% funding by ADP.

We obtained a list of prices that were submitted to the ADP over the 2018/2019 fiscal year that included the following codes for a KAFO with locked knees and hinged ankles (excluding ischial/gluteal weight bearing codes; ADP, personal communication, October 2020):

Thermoplastic or Carbon fibre lamination style LKAFO: including CNLCF1002, CNLCF2002, CNLCF3300, CNLCF3323

A total cost estimate of the LKAFO codes reimbursed by ADP in fiscal 2018/2019 was $667,436.65 (manual calculation; ADP, personal communication, October 2020). Assuming that 429 people received the device per year, we estimated an average cost per person of $1,555.80. We added to this the costs associated with the material and component codes ($3,974, see Table 11) to calculate an average cost of $5,529.80 for each LKAFO for people with 100% coverage and $4,147.35 for people with 75% coverage; see Appendix 6 for full calculations). This estimate was used to validate the average price estimates for a standard LKAFO that we obtained from experts ($6,151.00 and $4,613.25 for people with 100% and 75% coverage, respectively) and was also considered instead of our reference case estimate in one of our sensitivity analyses.

SCKAFOS

We made cost estimates for SCKAFOs based on expert opinion and categorized the estimates by the type of SCKAFO (i.e., mechanical, electronic, or microprocessor; OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, September 2020). A full list of SCKAFO device prices is shown in Table 12. In our reference case analysis, we used a conservative (maximum) price estimate for a mechanical SCKAFO of $10,784.49 and applied this amount to the 36% of people who received 100% coverage. We adjusted the cost to $8,088.37 for the 64% of people who received 75% coverage (Table 12). We used the maximum price of a mechanical SCKAFO, the most purchased SCKAFO in Ontario, in our reference case analysis (OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, September 2020). Mechanical SCKAFOs are funded by Alberta Aids to Daily Living (AADL) program, which provides funding for basic medical equipment and supplies for people with chronic health problems. We considered other prices for SCKAFOs in our sensitivity analysis.

Table 12:

Cost Estimates for SCKAFOs Used in Reference and Scenario Analyses

| Type of SCKAFO | Minimuma | ADP Funding,b $ | Maximum,a $ | ADP Funding (75%),b $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | ||||

| Labour cost | 3,469.58 | — | 6,434.49 | — |

| Device cost | 3,915 | — | 4,350 | — |

| Total | 7,384.58 | 5,538.44 | 10,784.49c | 8,088.37c |

| Electronic | ||||

| Labour cost | 7,002.24 | — | 11,228.82 | — |

| Device cost | 13,920 | — | 14,500 | — |

| Total | 20,922.24 | 15,691.68 | 25,728.82 | 19,296.62 |

| Microprocessord | ||||

| Total | 83,853.16 | 62,889.87 | 99,296.98 | 74,472.68 |

Abbreviations: ADP, Assistive Devices Program; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis.

Cost for people who are assumed to receive 100% funding by ADP in 2020 CAD. OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, October, 2020.

Manual calculation of 75% of full device costs in 2020 CAD.

Costs used in reference case analysis represent costs of a mechanical SCKAFO.

Microprocessor SCKAFOs could not be separated into cost components, as structuring the device is dependent on labour.

Internal Validation

The secondary health economist conducted formal internal validation. This process included checking for errors and ensuring the accuracy of parameter inputs and equations in the budget impact analysis.

Analysis

In the reference case analysis, we calculated the budget impact of publicly funding SCKAFO in adults with knee instabilities in Ontario. The budget impact is the cost difference between estimated total costs of the new scenario (public funding for SCKAFO and LKAFO) and the current scenario (public funding for LKAFO only). We did not present the budget impact broken down by cost type (i.e., labour and device costs) as many ADP codes combined professional time and materials. Our reference case analysis reflected the budget impact associated with publicly funding a basic (mechanical) SCKAFO. All our analyses were done from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and were expressed in 2020 CAD.

Sensitivity Analyses

Table 13 summarizes all scenarios that we ran as part of our sensitivity analysis to address variability in the costs of LKAFO and SCKAFO and to account for either slower or higher adoption of SCKAFO over the next 5 years. As a part of this analysis, we explored various price estimates.

Table 13:

Cost and Uptake Parameters Used in Scenario Analyses

| Scenario | Reference Case | Sensitivity Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | ||

| Scenario 1: low cost of a mechanical SCKAFO | ||

| 100% coverage 75% coverage |

$10,784.49a $8,088.37b |

$7,384.58a $5,538.44b |

| Scenario 2: low cost of an electronic SCKAFO | ||

| 100% coverage 75% coverage |

$10,784.49a $8,088.37b |

$20,922.24a $15,691.68b |

| Scenario 3: high cost of an electronic SCKAFO | ||

| 100% coverage 75% coverage |

$10,784.49a $8,088.37b |

$25,728.82a $19,296.62b |

| Scenario 4: low cost of a microprocessor SCKAFO | ||

| 100% coverage 75% coverage |

$10,784.49a $8,088.37b |

$83,853.16a $62,889.87b |

| Scenario 5: high cost of a microprocessor SCKAFO | ||

| 100% coverage 75% coverage |

$10,784.49a $8,088.37b |

$99,296.90a $74,472.68b |

| Uptake | ||

| Scenario 6: slow uptake of SCKAFO | 30% to 50% over 5 y | 30% in y 1, with a 3% annual increase over 5 y (reaching 42% in year 5) |

| Scenario 7: high uptake of SCKAFO | 30% to 50% over 5 y | 50% in y 1, with a 3% annual increase over 5 y (reaching 62% in year 5) |

| Additional Scenarios | ||

| Scenario 8: cost of an LKAFO using ADP submitted prices 100% Coverage 75% Coverage Scenario 9: 100% coverage for LKAFO and SCKAFO |

$6,151.00a $4,613.25a SCKAFO:$8,088.37 Coverage: 36% LKAFO: $4,613.25 Coverage: 64% |

$5,529.80c $4,147.35d SCKAFO: $10,784.49 Coverage: 100% LKAFO: $6,151.00 Coverage: 100% |

Abbreviations: ADP, assistive devices program; LKAFO, locked knee–ankle–foot orthosis; SCKAFO, stance-control knee–ankle–foot orthosis.

Note: scenarios 1–8 assume 36% of people received 100% ADP coverage and 64% of people received 75% ADP coverage.

OAPO Committee, Certified Orthotists, personal communication, 2020; Assistive Devices Product Manual.

Manual calculation of 75% of full price.

Manual calculation based on total ADP payments (Assistive Devices Program, personal communication, October 2020). See Appendix 6 for calculations.

75% of $5,529.80 full cost.

The three key types of SCKAFO device that we costed out were the mechanical, electronic, and microprocessor. The large range of prices for SCKAFO devices may be attributed to the materials and clinical hours needed to customize each class of device. To account for the range in prices in scenarios 1 to 5, we varied the price of the devices using minimum and maximum estimates for each class of SCKAFO (Table 13).

In addition, we explored variation in the uptake rates of SCKAFO (scenarios 6 and 7). In consultation with experts, some people who are eligible for a SCKAFO may choose to not use one, and only a proportion of people using an LKAFO may switch to a SCKAFO. In scenario 6, we modelled a slower uptake (30% in year 1, with a 3% increase each subsequent year, for a total of 772 people who chose a SCKAFO over 5 years) and, in scenario 7, we modelled a larger uptake (50% in year 1, with a 3% increase each year, for a total of 1,201 people who chose a SCKAFO over 5 years), compared to the gradual uptake assumed in our reference case (30% to 50% over 5 years, for a total of 858 people who chose a SCKAFO).

Because the price of an LKAFO can vary, we conducted a scenario validating price estimates provided by experts. In scenario 8, we estimated this price based on data from ADP and prices from the ADP product manual.7 See Appendix 6 for full calculations. Lastly, we conducted a scenario (scenario 9) assuming that all patients received 100% funding for LKAFO and SCKAFO devices. For this scenario, we used the full price estimated by Orthotists. Scenario 9 assumes that all patients receive full coverage and includes patients who may have a device that costs more to the ADP than standard SCKAFO and LKAFO devices (patients with only 75% coverage under the current scenario).

Results

Reference Case