Abstract

Purpose

Plasma membranes constitute a gathering point for lipids and signaling proteins. Lipids are known to regulate the location and activity of signaling proteins under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Membrane lipid therapies (MLTs) that gradually modify lipid content of plasma membranes have been developed to treat chronic disease; however, no MLTs have been developed to treat acute conditions such as reperfusion injury following myocardial infarction (MI) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). A fusogenic nanoliposome (FNL) that rapidly incorporates exogenous unsaturated lipids into endothelial cell (EC) membranes was developed to attenuate reperfusion-induced protein signaling. We hypothesized that administration of intracoronary (IC) FNL-MLT interferes with EC membrane protein signaling, leading to reduced microvascular dysfunction and infarct size (IS).

Methods

Using a myocardial ischemia/reperfusion swine model, the efficacy of FNL-MLT in reducing IS following a 60-min coronary artery occlusion was tested. Animals were randomized to receive IC Ringer’s lactate solution with or without 10 mg/mL/min of FNLs for 10 min prior to reperfusion (n = 6 per group).

Results

The IC FNL-MLT reduced IS (25.45 ± 16.4% vs. 49.7 ± 14.1%, P < 0.02) and enhanced regional myocardial blood flow (RMBF) in the ischemic zone at 15 min of reperfusion (2.13 ± 1.48 mL/min/g vs. 0.70 ± 0.43 mL/min/g, P < 0.001). The total cumulative plasma levels of the cardiac injury biomarker cardiac troponin I (cTnI) were trending downward but were not significant (999.3 ± 38.7 ng/mL vs. 1456.5 ± 64.8 ng/mL, P = 0.1867). However, plasma levels of heart-specific fatty acid binding protein (hFABP), another injury biomarker, were reduced at 2 h of reperfusion (70.3 ± 38.0 ng/mL vs. 137.3 ± 58.2 ng/mL, P = 0.0115).

Conclusion

The IC FNL-MLT reduced IS compared to vehicle in this swine model. The FNL-MLT maybe a promising adjuvant to PCI in the treatment of acute MI.

Keywords: Ischemia/reperfusion, Myocardial infarction, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Endothelium, Lipid rafts, Liposomes, Membrane lipid therapy

Introduction

Over the last decades, our understanding of cellular level processes has grown exponentially based on technological advances that allow the manipulation of structure and composition of nucleic acids and proteins. However, our understanding of the structure/function of lipids in plasma membranes has not progressed as rapidly. One of the major hurdles has been the inability to manipulate the membrane lipid composition as easily as other cellular molecules. The intricacy and asymmetry of lipid distribution across the lipid bilayer in plasma membranes adds an additional layer of complexity [1]. The concept that lipids can regulate the location and activity of many membrane signaling proteins is becoming firmly established in the literature [2–4]. This includes rigid plasma membrane lipid raft (LR) microdomains, rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids, that serve as platforms for interacting signaling proteins [4]. Additionally, there is evidence that membrane function is perturbed in a wide range of pathologies [5–7]. Alterations to plasma membranes would affect the localization of signaling proteins or protein-protein interactions in specific microdomains and thereby affect signaling cascades. The recognition that plasma membranes can serve as targets for therapeutic intervention has led to the development of membrane lipid therapies (MLTs) to treat or manage chronic diseases [8]. MLT-based clinical trials have been conducted using rationally designed lipids or natural lipids to chronically treat cancer or Alzheimer’s [8]. However, MLT-based therapies to treat acute conditions, such as ischemia/reperfusion injury (I/RI), are lacking. One of the reasons for this limitation is that lipid uptake by cells is in general relatively slow. Therapeutic lipids in cell culture studies require hours to days of incubation to elicit an effect [9–12]. In an effort to develop a fast-acting MLT to treat reperfusion injury (RI) in the acute myocardial infarction setting, our group developed a highly fusogenic nanoliposome (FNL) by combining unsaturated phospholipids (normally used to make our nanoliposomes) with small amounts of unsaturated docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P). This combination of lipids enhanced the FNL fusion rate with endothelial cells (ECs) and allowed the rapid incorporation of exogenous unsaturated lipids into plasma membranes. FNL treatment appears to interfere with plasma membrane protein signaling, and therefore, after a few minutes of application, the EC lipid bilayer can be modified to attenuate RI. The idea of developing a fast-acting FNL-MLT was based on our group’s prior work with an early version of a fusogenic nanoliposome designed to enhance the preservation of isografts in a rat heterotopic heart transplantation model [13]. In those studies, hearts were preserved at 27 °C for 15 min and at 4 °C for 45 min with nanoliposomes in St. Thomas organ preservation solution, and following transplantation, the hearts had reduced dysfunction and lower plasma levels of the myocardial injury biomarker cardiac troponin I (cTnI) [13].

The purpose of the present study was to demonstrate that a novel FNL-MLT has the potential for clinical application in the acute treatment of myocardial I/RI. In cell culture studies, we provide new insights regarding the importance of FNL lipid formulation on the fusion rate with cells, which dictates the rate at which the lipid composition of membranes is modified. Also, the distribution of FNL lipids into endothelial cell (EC) membrane caveola/lipid raft (C/LR) microdomains is characterized following fusion. Additionally, the effects of FNL-MLT on inhibiting EC and macrophage activation following pro-inflammatory stimulation are presented. Lastly, studies using a closed chest swine model of myocardial I/RI were performed to establish whether the microvascular bed endothelium associated with the infarct-related artery can be targeted by intracoronary (IC) administration of FNLs to treat postischemic endothelial dysfunction and reduce myocardial infarct size (IS). We hypothesized that FNL incorporation of exogenous unsaturated lipid into EC membranes, just prior to reperfusion, would interfere with reperfusion-induced pro-inflammatory protein signaling and thereby reduce microvascular dysfunction and IS expansion. Our results provide insight into the potential development of a fast-acting MLT to treat myocardial I/RI.

Methods

Animals

Three-month-old female Yorkshire swine weighing 19–28 kg were used for this study. All swine were housed in a temperature-controlled animal facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle, with water provided ad libitum, and pig chow provided twice daily. All animals were cared in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health and Human Services, Publication No. [NIH] 86–23).

FNL Preparation

The preparation of liposomes was performed as previously described by Goga et al. with a few minor modifications [14]. In brief, the FNL developed for the present study consisted of the following lipids mixed in chloroform: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (PC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (PA), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE) (Cat. #s 850375C, 840875C, and 850725C, respectively, Avanti Lipids International, Alabaster, AL), in a 1.8:2.4:1 M ratio, with 5% DHA (Cat. # D2534, Sigma-Aldridge, St. Louis, MO) and 0.5% S1P (PC/PA/PE-DHA/S1P) (Cat. # 860492, Avanti Lipids International, Alabaster, AL). The chloroform was removed using a vacuum pump and by blowing nitrogen gas. The lipid material was hydrated in lactated Ringer’s solution to a concentration of 10 mg/mL of lipid. The resulting solution was sonicated with a Branson Sonifier 450A (Branson Ultrasonics Corp, Danbury, CT) at 50% duty cycle for 1 min/mL to form smaller unilamellar FNLs. The solution was repeatedly extruded through the membranes with progressively smaller pore sizes (400 nm, 200 nm, and 100 nm) using a Thermobarrel Extruder (Northern Lipids, Burnaby, BC, Canada). The same manufacturing process was used to generate nanoliposomes hydrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and formulated with PC alone or PC/PA/PE at a 1.8:2.4:1 M ratio for fusion studies, and for lipid tracking studies, nanoliposomes were formulated with PC/PA and rhodamine-labeled 1,2-di-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-[(N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl) iminodiacetic acid) succinyl] zinc salt (Rho-DOGS) in a 1.8:2.4:1 M ratio (PC/PA/Rho-DOGS) (Cat. # 790528C, Avanti Lipids International, Alabaster, AL). Nanoliposome characteristics including particle size, concentration of particles, and zeta potential were quantified using a ZetaView Multiple Parameter Particle Tracking Analyzer (Particle Metrix Inc., Mebane, NC).

FNL Fusion Study

Primary mouse coronary artery endothelial cells (MCAECs) (Cat. # C57–6093, Cell Biologics, Chicago, IL) were seeded in a 96-well plate (3.5 × 104 cells/well) in complete endothelial cell culture medium (Cat. # 15–017-CV, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) and incubated at 37 °C (5% CO2, 99% humidity) until they reached 90% confluency. Three different liposome formulations were tested: PC only; PC/PA/PE (the main lipid components of the FNL formulation); and PC/PA/PE-DHA/S1P (the novel FNL formulation). To quantify FNL fusion rate, FNLs (10 mg/mL) were labeled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3’-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DiR), an infrared dye that is transferred into cell membranes as FNLs fuse with cells. A stock solution of 12.5 mg/mL of DiR in ethanol was diluted to generate a standard curve. The DiR signal was measured using the bottom read feature of a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader running Softmax Pro software (MolecularDevices, Sunnyvale, CA) with filters set at 760 nm excitation and 800 nm emission. The rate of fusion was quantified over a 15-min period and expressed as DiR relative fluorescence units (RFU)/concentration of FNL particles/min.

Microscopy Studies of Nanoliposome Lipid Incorporation into EC C/LR Microdomains

Primary mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) (Cat. # C57–6052, Cell Biologics, Chicago, IL) were grown in collagen-coated glass-bottom single-well plates in DMEM/F-12 (Cat. # 10–092-CV, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA). To identify the location of C/LR microdomains on EC membranes, MAECs were transfected with green fluorescence protein (GFP)-flotillin-1 cDNA plasmids following the protocol described by Ketchem et al. [15]. Briefly, MAECs were washed with serum-free Opti-MEM (Life Technologies Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and transfected with 750 μL of Opti-MEM containing 0.1 μg/mL of GFP-flotillin-1 cDNA using 5.0 μL/mL of Lipofectamine LTX. Plates were vortexed and incubated at 37 °C for 6 h in a humidified incubator. Then, 750 μL/mL of media with 20% fetal bovine serum was added to wells and allowed to incubate overnight. The next day, 2 h before starting the experiment, cells were washed with serum-free OPTI-MEM. MAECs at 30% confluency were then treated with 1 ng/mL of nanoliposomes formulated with PC/PA/Rho-DOGS in serum-free OPTI-MEM. During microscopy, oxygen was provided by ambient air, which was supplemented by 5% CO2 and warmed to 37 °C in an environmental chamber surrounding the specimen. To visualize in live MAECs, the membrane distribution of lipid incorporated by nanoliposome-MLT in relation to caveolae/lipid rafts, a combination of advanced microscopy imaging techniques was utilized including epifluorescence (Epi), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF). MAECs were imaged with a custom Olympus FRET/TIRF microscope (Center Valley, PA) with a high-resolution Hamamatsu camera. FRET and TIRF image acquisition and analysis was performed using SlideBook software version 4.2. FRET analysis was performed using the three-filter “micro-FRET” image subtraction method described by Jiang and Sorkin [16]. Briefly, two images (100-ms or 250-ms exposure sets, 2 × 2 binning) were obtained: an mCherry excitation/mCherry emission image and a GFP excitation/GFP emission image (raw, uncorrected FRET). After imaging, background images were taken. Background-subtracted mCherry and GFP images were fractionally subtracted from raw FRET images based on measurements for GFP bleed-through (0.50–0.56) and mCherry cross-excitation (0.015–0.02). This fractional subtraction generates corrected FRET (FRETc) images. This fractional subtraction was represented in pseudocolor (gated to mCherry acceptor levels), showing sensitized FRET within cells. The subtraction Pearson’s coefficients were rounded up from average cross-bleed values determined in MAECs expressing GFP- or rhodamine-tagged constructs alone. Thus, these coefficients result in the underestimation of FRETc signals for true FRET partners but prevent false positive detection of FRET. TIRF microscopy was performed as described by Ketchem et al. with slight modifications [15]. Briefly, samples were observed using the same microscope and image capture system as described above. Laser excitation for TIRF experiments was derived from a multiline argon ion laser run at the same setting for all experiments. The power at the sample was controlled by a neutral density filter wheel. Excitation and emission wavelengths were selected using filters set for mCherry (rhodamine) and GFP. The laser was aligned per the manufacturer’s instructions to achieve TIRF illumination.

Endothelial Cell Activation Study

MCAECs were seeded in a 96-well plate (3.5 × 104 cells/well) in complete cell culture medium and incubated at 37 °C (5% CO2, 99% humidity) until they reached 90% confluency. Plastic-contact-activated plasma (PCAP) was generated by collecting heparinized pig whole blood in polypropylene tubes, placing them on a rocker at a moderate speed for 90 min. Tubes were centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 min; PCAP was collected, divided into 1.5 mL aliquots, and frozen at − 80 °C until use. MCAECs were pretreated for 20 min with 2.5, 5.0, or 10.0 mg/mL of FNL lipid and incubated for 2 h with a 4 × dilution of PCAP in media. Cells were washed and incubated with media for an additional 1 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 100 μL of 1% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 30 min. A modified ELISA assay was used to quantify ICAM-1 expression. Cells were washed thrice and 100 μL (1 μg/mL) of Armenian hamster primary anti-mouse ICAM-1 antibody (Cat. # MA5405, RRID:AB_223595, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in 5% serum albumin BSA/PBS was added to wells. Cells were washed thrice, and a 200-fold dilution in 5% BSA/PBS of rabbit anti-hamster secondary antibody (Cat. # A18889, RRID:AB_2535666, ThermoFisher Scientific) labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added to wells. Both antibodies were incubated on ice pads for 45 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS, and 100 μL of tetramethylbenzidine solution were added to wells until color developed (approximately 15 min). Then, 100 μL of stop solution were added, and absorbance at 450 nm was read using a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader.

Macrophage Activation Study

Mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Cat# TIB-71, RRID:CVCL_0493) were seeded in a 96-well plate (3.5 × 104 cells/well) in complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Cat. # 10–013-CV, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) and incubated at 37 °C (5% CO2, 99% humidity) until they reached 90% confluency. Cells were pretreated for 10, 20, and 30 min with 2.5 mg/mL of FNLs formulated with PC/PA/PE-DHA/S1P. RAW cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 18 h at 37 °C. Supernatant levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha were quantified using a mouse TNF ELISA kit (Cat. # KMC3012, ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY), and a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader absorbance was read at 450 nm. Two controls were used: cells without treatment and cells treated with LPS.

Myocardial Infarction Study

The technique for eliciting myocardial infarction was performed as described by Jones et al. [17]. Briefly, swine were subjected to a catheterization procedure to induce myocardial infarction under general anesthesia. Swine were anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine (20 mg/kg, i.m.) and xylazine (2 mg/kg, i.m.) followed by a continuous infusion of Brevital (5.5–12.0 mg/kg/h, i.v.). Arterial blood gases were taken routinely to ensure physiological stability. Swine were instrumented with a venous catheter for blood sampling, a pigtail catheter in the left ventricle (LV) for administration of microspheres, and an over-the-wire balloon catheter was placed in the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. Myocardial infarction (MI) was induced by a 60-min balloon occlusion followed by reperfusion. Animals were randomized to receive at the 50th min of occlusion, an IC infusion of 10 mL of Ringer’s lactate with or without 10 mg/mL of FNLs (n = 6 per group), delivered at a rate of 1 mL/min via the central lumen of the balloon catheter. At 1 h of occlusion, the balloon was deflated to allow reperfusion, and animals were allowed to recover. At 72 h of reperfusion, the hearts were harvested and the non-ischemic zone (NIZ) of the hearts was stained with phthalo blue dye and the ischemic zone (IZ) with triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) red dye. The hearts were sectioned into 7–8 transverse slices (~1 cm in thickness) and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde for 24 h. The slices were weighed and photographed, and images were analyzed using Image J software to quantify NIZ, IZ, infarcted area (IA), and area at risk (AAR) [17].

Plasma Levels of Cardiac Troponin I and Heart-Specific Fatty Acid Binding Protein

Plasma levels of the heart injury biomarker cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and heart-specific fatty acid binding protein (hFABP) were quantified. Heparinized blood samples were collected at baseline and 2, 4, 6, 24, and 48 h after reperfusion. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm at room temperature; plasma was collected, aliquoted, and stored at − 80 °C until use. Plasma was analyzed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions for swine cTnI (Cat. # CTNI-9; Life Diagnostics, Inc. West Chester, PA.) and hFABP (Cat. # HFABP-9; Life Diagnostics, Inc. West Chester, PA). Plasma samples were thawed and diluted using the standard diluent provided with the kits. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm for both cTnI and hFABP using a SpectroMax M2e microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Cumulative total levels of cTnI were determined over 48 h of reperfusion using the trapezoidal rule to quantify the area under the curve. Levels of hFABP were quantified at baseline, 2, and 4 h of reperfusion.

Regional Myocardial Blood Flow Measurements

RMBF was quantified using the method described by Reinhardt et al. [18] Briefly, 2 mL of a designated microsphere isotope (Samarium #1, Europium #2, Lutetium #3, or Lanthanum #4) was infused through the LV pigtail catheter for over 30 s, while a reference sample of blood was withdrawn simultaneously from the femoral artery. LV specimens from the IZ and NIZ were obtained and quantified for microsphere content to determine RMBF. Measurements were made at baseline, 45 min of ischemia, and 15 min and 72 h of reperfusion. Tissue and reference blood samples were processed by BioPAL using neutron activation technology of microsphere content.

Statistical Analysis

Cell cultured studies consisting of more than three groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Sidak post hoc pairwise comparisons. FNL fusion studies were analyzed using linear regression analysis and Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Cell culture studies consisting of two groups were analyzed using the Student t tests. Infarct size reduction and cumulative cTnI were analyzed using a Student t test. Serial temporal analysis of RMBF, cTnI, and hFABP was performed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni or Holm-Sidak post hoc pairwise comparisons. FRET images were analyzed utilizing the SlideBook4.2 software. A test was deemed significant if the P value was < 0.05. All values are reported as mean ± SD.

Results

FNL-to-EC Fusion Studies

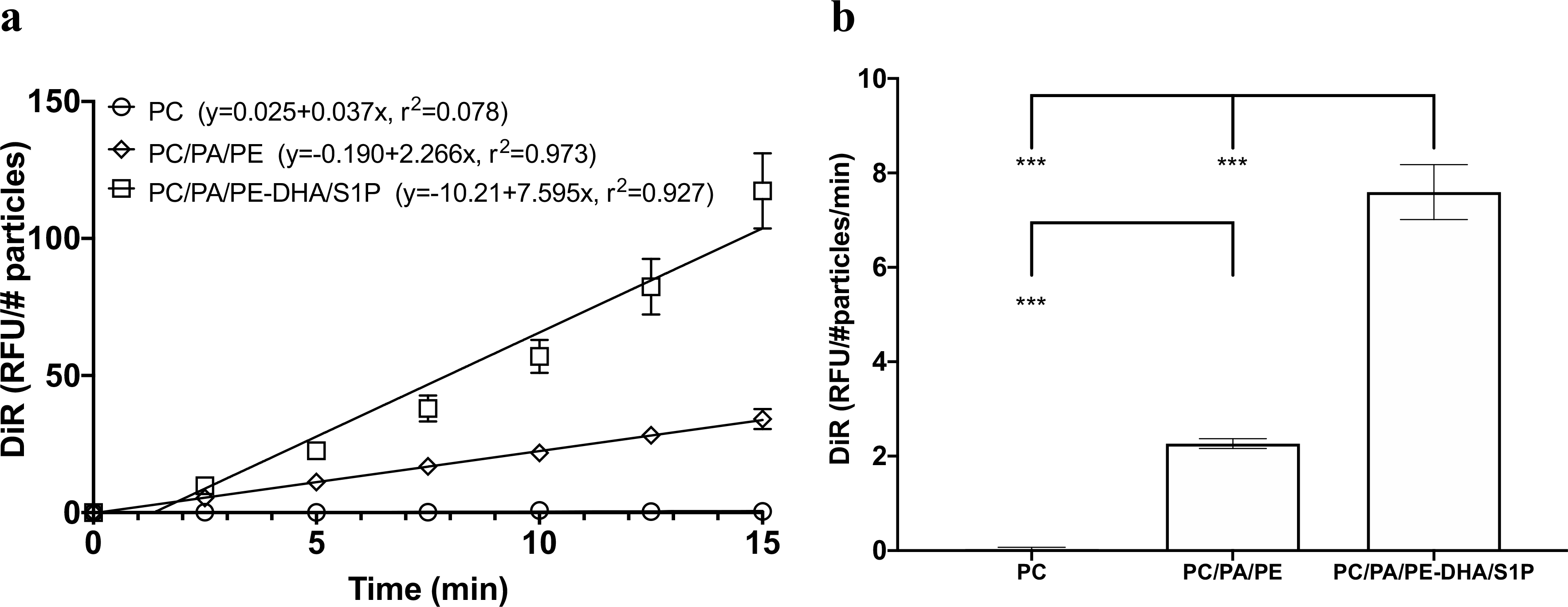

To demonstrate that the FNL lipid formulation is responsible for enhancing the fusion rate, two less fusogenic nanoliposomes were created: one formulated with PC, the other with PC/PA/PE, and all were compared. Vesicles were labeled with DiR, and the amount of dye transferred to MCAEC plasma membranes over time was quantified. The results showed that the slope of the FNL curve was steeper than that of the two nanoliposomes (Fig. 1A) and that the rate of fusion derived from the slopes was higher for FNLs than the two other nanoliposomes tested (Fig. 1B). It was apparent that adding small percentages of DHA and S1P to FNL formulation significantly enhanced the fusion rate.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of fusogenic characteristics of FNLs (PC/PA/PE-DHA/S1P) and nanoliposomes partially formulated with FNL lipid components (PC only or PC/PA/PE). MCAECs were incubated with FNLs or nanoliposomes labeled with DiR (a lipophilic infrared dye). The incorporation of DiR into cell membranes was quantified every 2.5 min using a microplate reader. (a) Fusion kinetic curves generated by FNLs and nanoliposomes; DiR incorporation was measured in terms of relative fluorescence units (RFU)/concentration of number of FNL particles (#particles). (b) Comparison of fusion rates calculated from the slope of best fit line through the data points for FNLs and nanoliposomes. Data are shown as mean ± SD; ***P < 0.001

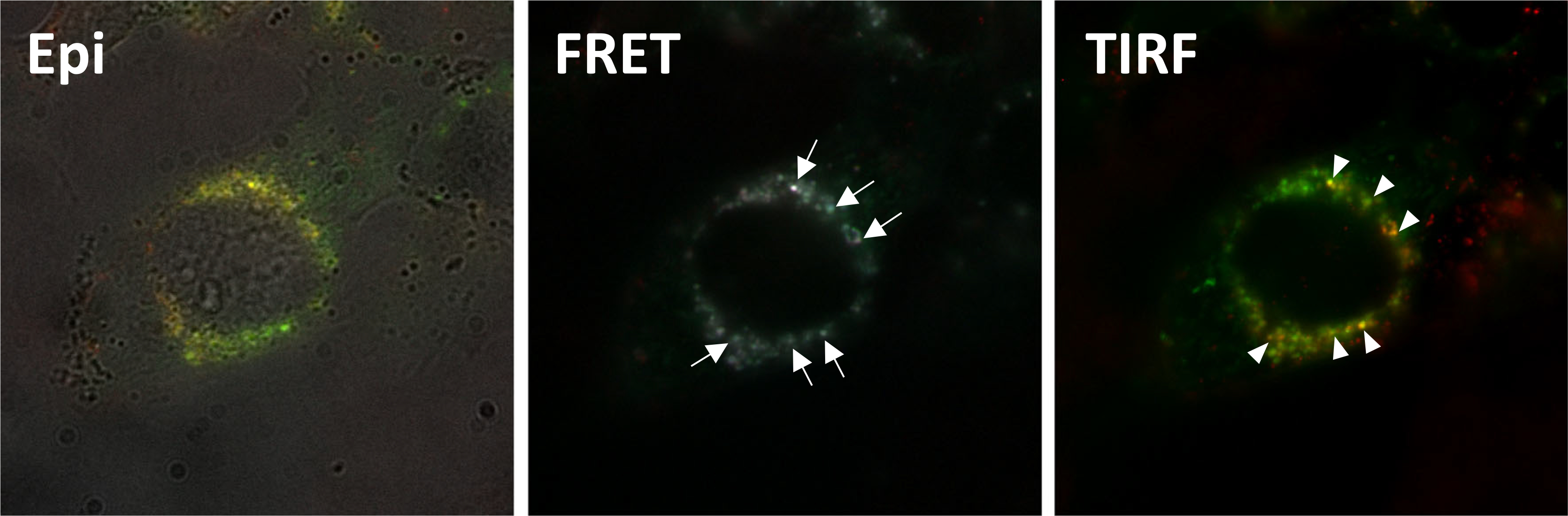

FNL-MLT Incorporates Exogenous Lipid into C/LR Microdomains

To track the distribution of monounsaturated lipid incorporated into MAEC membranes, FNLs were formulated with Rho-DOGS lipid to allow visualization in live cells. MAECs transiently transfected with GFP-flotillin-1, a caveolae/LR protein, were treated with rhodamine-labeled nanoliposomes. Live imaging was performed using a FRET/TIRF microscope. As shown in Fig. 2, three-channel FRET analysis showed a calculated Pearson’s coefficient of 0.78 ± 0.19 (n = 33 cells), suggesting a strong interaction between FNL-incorporated Rho-DOGS and GFP-flotillin-1. TIRF microscopy results demonstrated that GFP-flotillin-1 and Rho-DOGS were localized in the MAEC plasma membrane, suggesting that lipid incorporation by FNLs is probably partially mediated by C/LR microdomains.

Fig. 2.

Representative images from Epi, FRET, and TIRF microscopy studies using live MAECs transfected to express GFP-flotillin-1 and incubated with rhodamine-labeled fusogenic nanoliposomes (PC/PA/Rho-DOGS). Epi shows a merged image of light microscopy, rhodamine, and GFP signals. FRET shows merged images of Rho-DOGS lipid and GFP-flotillin-1 interacting with each other (arrows). TIRF shows merged images demonstrating that Rho-DOGS and GFP-flotillin-1 are in close proximity to each other (yellowish dots) at the level of the cell membrane (pointers)

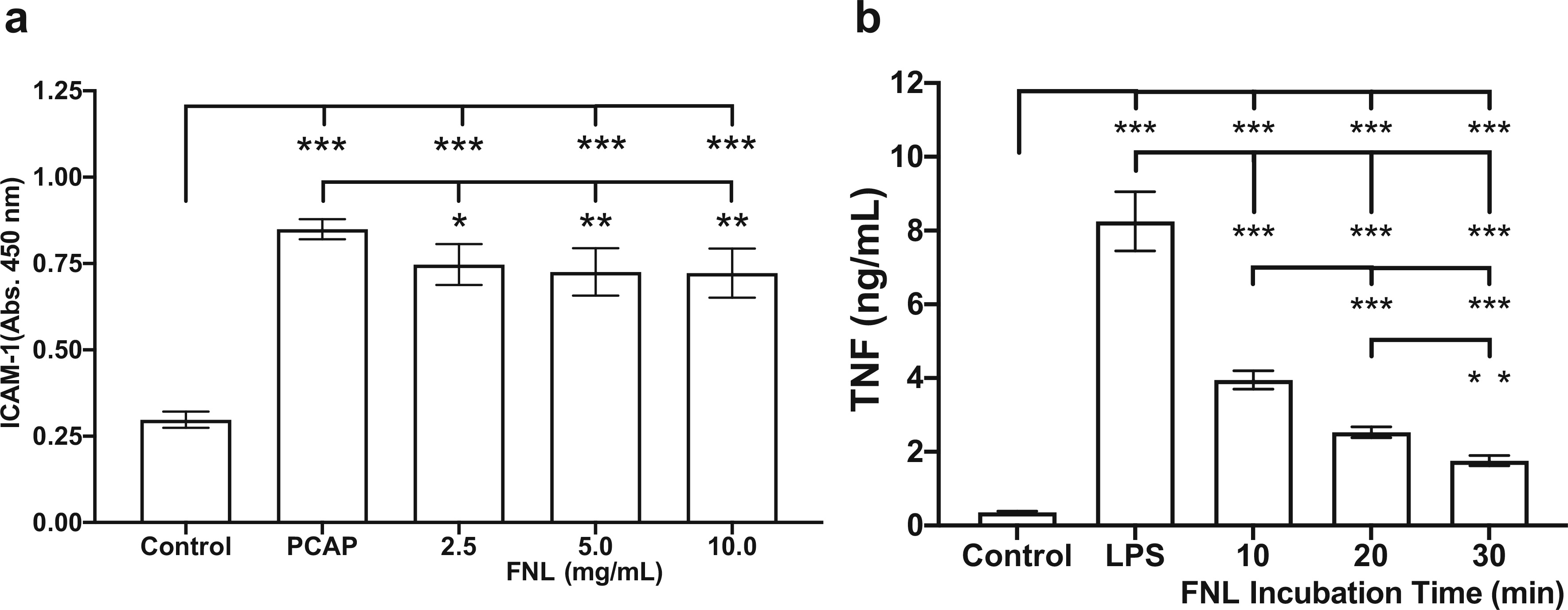

Effect of FNL-MLT on Cell Activation

To demonstrate that FNL-MLT interferes with the pro-inflammatory response, MCAECs were pretreated for 20 min with three different concentrations of FNLs and incubated with PCAP. To assess the efficacy of the MLT in attenuating the MCAEC pro-inflammatory response, ICAM-1 expression was quantified. The results showed that the three concentrations of FNLs significantly reduced ICAM-1 expression compared to controls (Fig. 3A). These findings provide evidence that rapid incorporation of unsaturated lipid into plasma membranes attenuates the MCAEC activation response.

Fig. 3.

Effect of FNL-MLT on the activation of MCAECs and RAW cells. (a) MCAEC ICAM-1 expression was quantified after pretreatment with FNLs (2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/mL) and incubation with activated plasma (PCAP) for 2 h, followed by a 1-h incubation with growth medium. (b) RAW cell TNF production was quantified after pretreatment with FNLs (2.5 mg/mL) for 10, 20, and 30 min and incubation with LPS for 18 h. Values are shown as mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

To demonstrate that FNL-MLT alters the pro-inflammatory response of macrophages, RAW cells were pretreated with FNLs for 10, 20, and 30 min and pulsed with the Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) agonist LPS overnight. The efficacy of the FNL-MLT was assessed by quantifying TNF released into the supernatant. The results demonstrated that a 10-min FNL pretreatment reduced TNF production in half compared to controls pulsed with LPS (Fig. 3B). A 30-min FNL pretreatment further reduced TNF production to ~25%. These findings provide evidence that FNL-MLT attenuates the RAW cell TLR4 response and has the potential to attenuate in vivo the contribution of pro-inflammatory macrophages in I/RI.

Effect of FNL-MLT on Myocardial Infarct Size

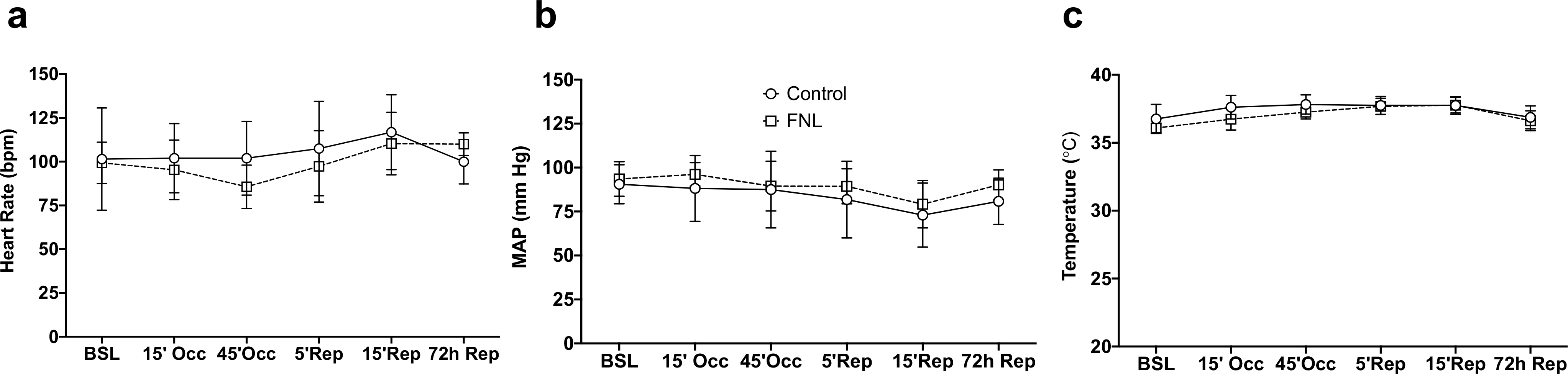

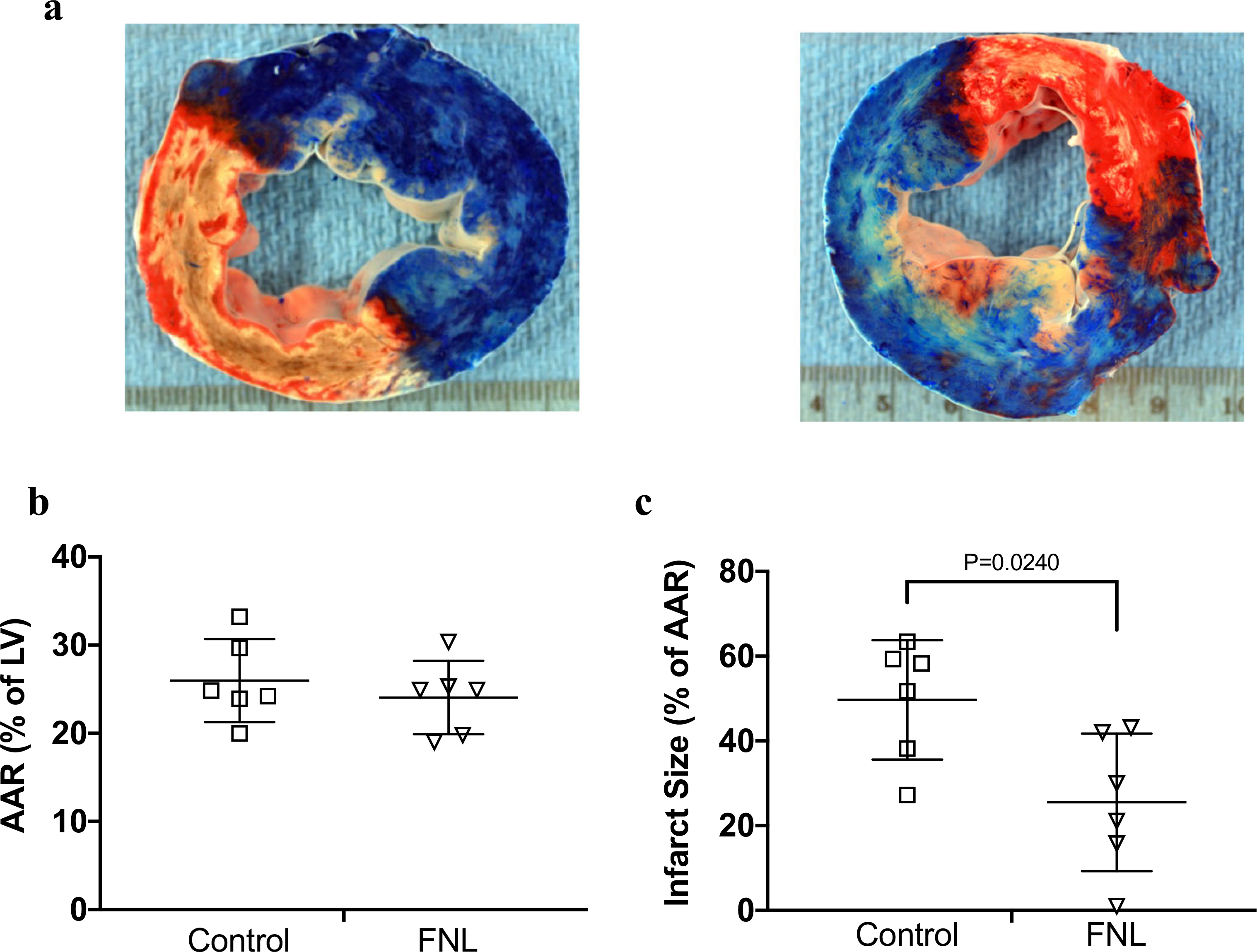

A total of 18 swine were included in the study. Five swine died during the occlusion procedure due to ventricular fibrillation. Seven pigs received vehicle (Ringer’s Lactate) and six received FNL-MLT. One pig in the vehicle group was hypothermic (34 °C) during the occlusion procedure and thus was excluded. In summary, a total of 12 pigs (n = 6 per group) were included in the final analysis. Table 1 and Fig. 4 summarize basic variables measured during the study. Representative LV slice images of vehicle and FNL-treated hearts are shown in Fig. 5A. The areas stained with blue dye indicate the NIZ. The IS created by balloon occlusion was quantified as the ratio of the IA relative to the AAR and expressed as a percentage. The AAR between the two groups was comparable (Fig. 5B). IS expressed as a percentage of AAR was reduced in the FNL-MLT group compared to vehicle (Fig. 5C).

Table 1.

Summary of basic variables and postmortem measurements

| Variable | Control (n = 6) | FNL-MLT (n = 6) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (days) | 82.3 ± 15.2 | 87.2 ± 4.9 | 0.478 |

| Body weight (kg) | 23.2 ± 2.9 | 25.8 ± 1.2 | 0.082 |

| Number of defibrillations | 2.3 ± 2.9 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.211 |

| Heart weight (g) | 213.9 ± 18.4 | 212.5 ± 22.4 | 0.900 |

| LV weight (g) | 99.3 ± 10.8 | 105.7 ± 11.3 | 0.345 |

| Risk region weight (g) | 25.8 ± 2.3 | 25.2 ± 3.8 | 0.833 |

| Infarct weight (g) | 12.9 ± 5.24 | 6.7 ± 4.6 | 0.054 |

Fig. 4.

Hemodynamic and temperature data of vehicle (control) and FNL-treated swine throughout the study. There was no difference between groups for any of the variables. Data are shown as mean ± SD

Fig. 5.

Infarct size analyses from swine hearts treated with IC vehicle (control) or IC FNLs following a 60-min LAD occlusion and 72 h of reperfusion. (a) Representative images of LV slices stained to distinguish the NIZ (phthalo blue dye) and the IZ (TTC red dye). The left panel shows a slice with transmural infarction with hemorrhage (white/beige color) from a vehicle-treated heart, and the right panel shows a slice with patchy infarction from an FNL-treated heart. (b) Illustrates that the AAR expressed as a percent of the LV was similar for both groups. (c) Demonstrates that the IS expressed as a percent of the AAR was statistically significant between groups. Data are shown as mean ± SD

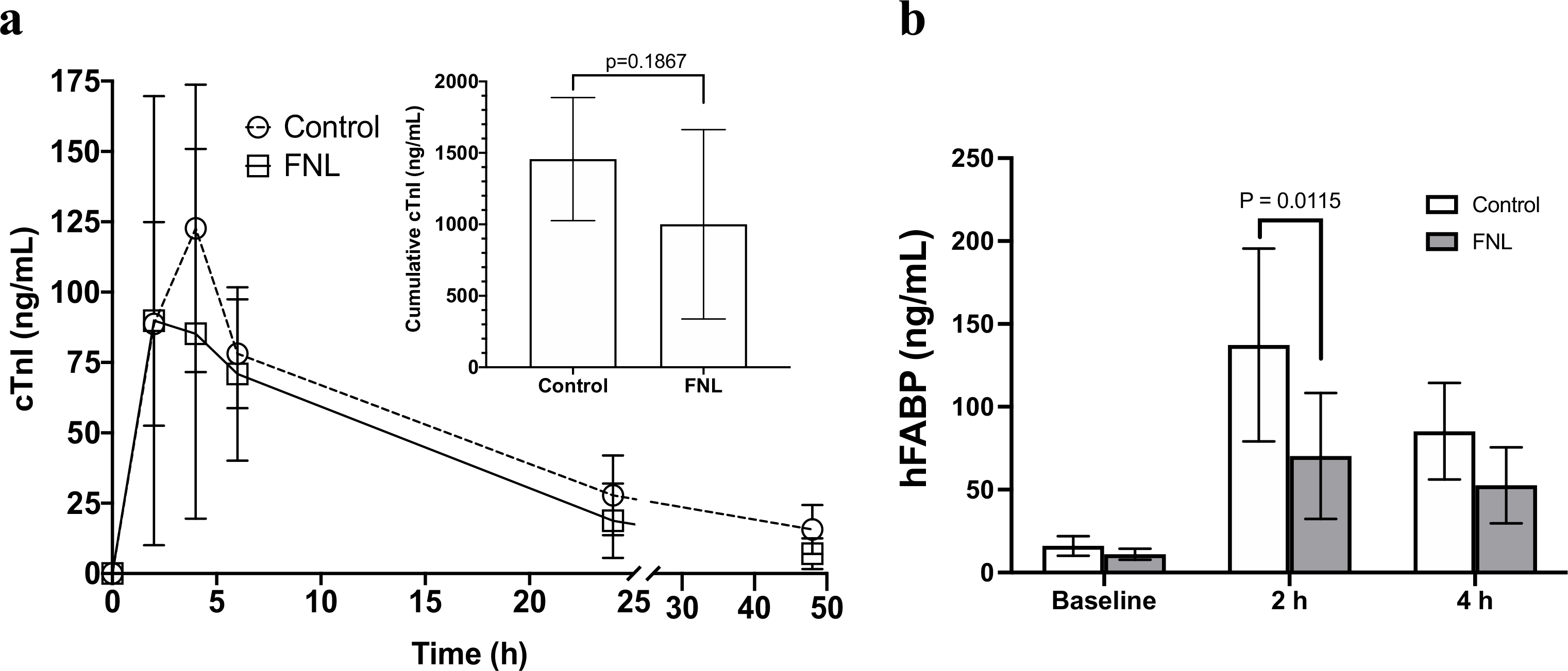

Effect of FNL-MLT on Plasma Levels of cTnI and hFABP

The total cumulative plasma levels of the myocardial injury biomarker cTnI were quantified. The results demonstrated a wide range of variability in peak plasma levels of cTnI between animals in both groups. The comparison of total cumulative levels of cTnI released were trending down but were not statistically significant between groups (Fig. 6A). However, plasma levels of hFABP at 2 h of reperfusion were significantly reduced in FNL-treated hearts (Fig. 6B) and appear to agree with IS findings.

Fig. 6.

Change in plasma levels of the cardiac injury biomarkers cTnI and hFABP following a 60-min LAD occlusion. Swine hearts were treated with IC vehicle (control) or IC FNLs 10 min prior to myocardial reperfusion. (a) Serial cTnI plasma levels (line graph) and calculated cumulative levels of cTnI released (inset bar graph) are presented. (b) Levels of hFABP at baseline, 2, and 4 h of reperfusion are shown. Data are shown as mean ± SD

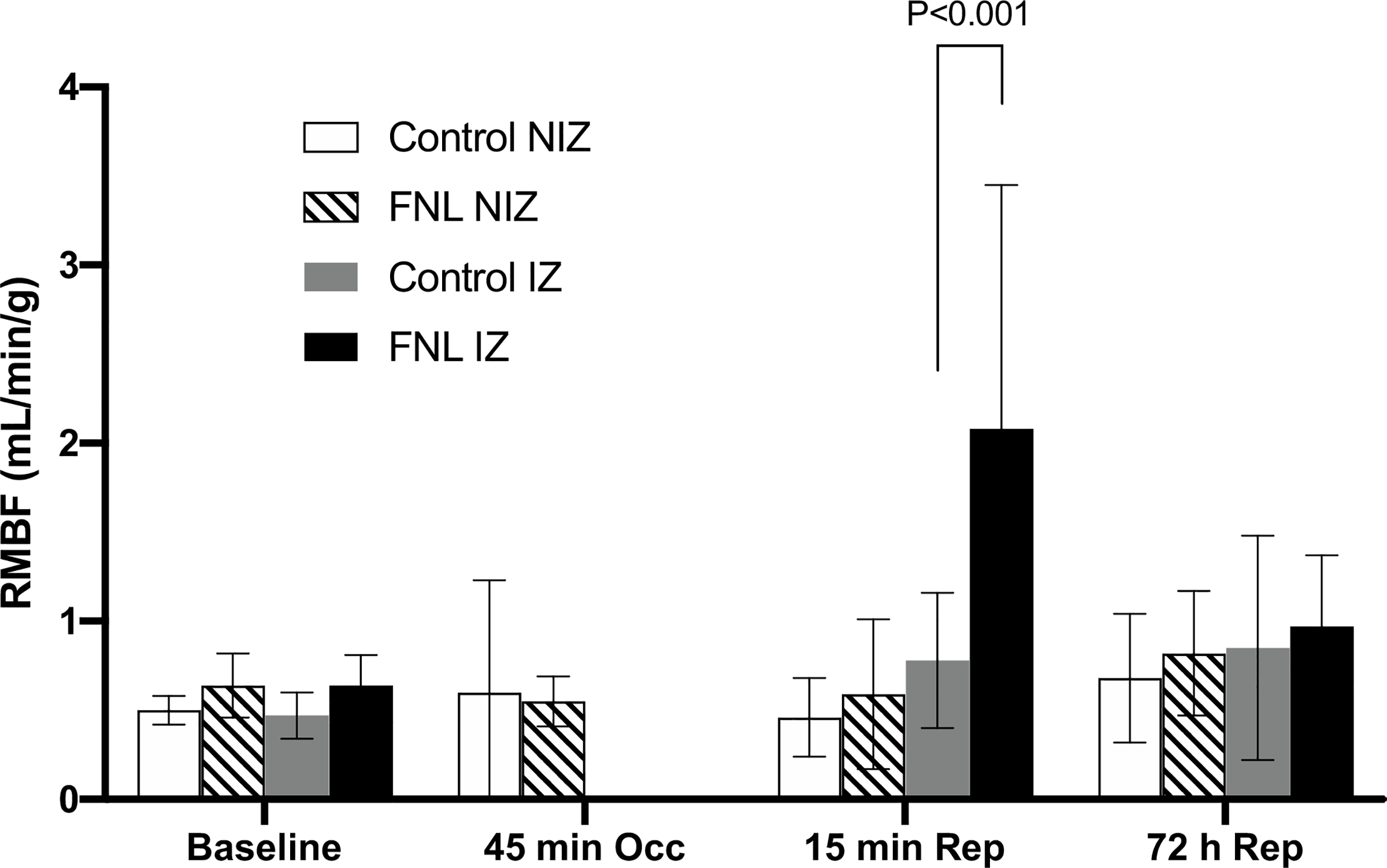

Effect of FNL-MLT on RMBF

To assess RMBF in the IZ and NIZ, neutron-activated microspheres were utilized. The results demonstrated that at baseline, there was no difference in RMBF in the IZ and NIZ between FNL-treated hearts and controls (Fig. 7). Also, RMBF analysis confirmed the absence of blood flow in the IZ of both groups during balloon occlusions of the LAD, indicating comparable ischemic insults. Interestingly, the mean RMBF in the IZ of FNL-treated hearts was ~ threefold higher than in controls at 15 min of reperfusion, suggesting that FNL-MLT appeared to attenuate microvascular dysfunction at this time.

Fig. 7.

RMBF data from swine hearts treated with IC vehicle (control) or IC FNLs before and after myocardial infarction. The mean RMBF was measured in the LV’s IZ and NIZ using four different neutron-activated microspheres administered at baseline, 45 min of occlusion (Occ), 15 min of reperfusion (Rep), and 72 h of reperfusion. At 15 min of reperfusion, RMBF increased by ~ threefold in the IZ of FNL-treated hearts suggesting a decrease in microvascular dysfunction. Data are shown as mean ± SD

Discussion

The major finding of the current investigation was that IC delivery of FNLs just prior to reperfusion reduced myocardial IS. The conceived therapeutic strategy envisioned that FNL administration would reduce reperfusion-induced pro-inflammatory protein signaling by increasing levels of unsaturated lipid in EC plasma membranes. The goal was to attenuate key pathophysiological events including the permeabilization of the microvascular endothelial barrier and the interactions between activated ECs, leukocytes, platelets, and myocardium. Developing a fast-acting FNL-MLT to treat I/RI has gradually evolved over the past 15 years. Our group has developed various fusogenic nanoliposome formulations for the preservation of organs utilized in transplantation [13, 19]. The results of the FNL fusion kinetic studies emphasized the importance of vesicle formulation and that small changes in composition greatly influenced nanoliposome fusion characteristics. Nanoliposomes formulated with one or three of the FNL lipid components had much slower fusion rates than FNLs. Pretreatment of FNL-MLT in cultured ECs and macrophages with FNL-MLT reduced the cell activation response (Fig. 3), suggesting that the incorporation of exogenous unsaturated lipid into plasma membranes attenuated pro-inflammatory protein signaling of two key cell types involved in RI. However, the mechanism by which FNL-MLT exerts its cardioprotective effect remains unclear. A mechanistic clue was provided by our high-resolution FRET and TIRF imaging studies in which FNL rhodamine-labeled lipids were found to closely interact with GFP-flotillin-1, a protein associated with C/LR microdomains. It appears that FNL unsaturated lipids disperse into these microdomains increasing their fluidity and perhaps interfering with C/LR assembly/function and protein signaling. There is evidence in the literature that treating ECs and immune cells with unsaturated lipids blunts the cell activation response and induces the displacement of signaling proteins in C/LR microdomains [9–12].

The potential application of FNL-MLT in the clinical setting to treat postischemic myocardial RI requires an understanding of the pathophysiology and the current management of patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Recanalization of the infarct-related artery with PCI often leads to IS expansion, due to postischemic endothelial dysfunction leading to abnormal tissue perfusion known as the “no-reflow” phenomenon [20, 21]. Patients experiencing “no-reflow” have poor infarct healing and adverse left ventricular remodeling, two factors known to increase risk for major adverse cardiac events including congestive heart failure (CHF) and death [22]. A number of PCI adjuvant therapies to treat STEMI and reduce reperfusion-induced microvascular dysfunction have undergone clinical trials with disappointing results [22, 23]. To address this unmet medical need, IC FNL-MLT was tested in a swine model of I/RI, which, apart from primate models, best resembles human heart anatomy and infarct pathology. IC FNL-MLT was delivered prior to reperfusion out of the concern that coronary blood flow during reperfusion would interfere with the ability of FNLs to fuse with ECs, which would reduce the therapeutic effect. The duration of IC FNL administration was based on FNL fusion kinetic studies and RAW cell activation studies, demonstrating that a 10-min FNL incubation period incorporated sufficient amounts of exogenous lipid into plasma membranes and was effective in reducing TNF production, respectively. Furthermore, we postulated that IC FNL-MLT administered prior to reperfusion would have the best chance to mitigate reperfusion-induced signaling cascades associated with EC expression of adhesion molecules and the recruitment of damaging PMNs. IC delivery ensured that a maximal number of FNLs come in contact and fuse with endothelial cells in the LAD’s downstream microvessels. Although the hearts receiving FNL-MLT had smaller IS, the serial plasma levels and calculated total plasma levels of cTnI over 48 h were trending down in the FNL-MLT group, but were not significant. This discrepancy may be explained by the small group size and high variability in plasma cTnI levels, which made this variable not sufficiently powered to detect a difference. To clarify this discrepancy, the injury biomarker hFABP was quantified. Unfortunately, the timing of our blood samples was unsuitable to capture the hFABP peak levels (between 30 and 60 min of reperfusion [24]) to calculate total cumulative levels released. However, at 2 h of reperfusion, hFABP levels were significantly reduced by FNL-MLT, and these results agree with IS findings.

IS reduction in the FNL-treated hearts suggests a curtailment of reperfusion-induced microvascular dysfunction and the no-reflow phenomenon. The microsphere data during early reperfusion demonstrated a threefold increase in RMBF in the IZ of the treated hearts (Fig. 7) implying a reduction of postischemic microvascular dysfunction. However, by 72 h, the enhanced blood flow had dissipated. It is important to point out that microsphere flow measurements may not be the most accurate marker of the no-reflow phenomenon because two important determinants of flow, perfusion pressure and vascular resistance, were not measured. For a more definitive answer regarding no-reflow, future studies using thioflavin-S staining should be performed. FNL-MLT may protect against loss of coronary flow reserve during reperfusion in a similar fashion as adenosine administration [25]. Interestingly, IS reduction attained with FNLs was comparable to published data from ischemic preconditioning (IP) studies using the same swine model [17]; however, unlike our present findings, early reperfusion RMBF in IP-treated hearts was not significantly different from the controls. The mechanism for the exaggerated hyperemic response observed in our model may be due to the delivery of phospholipids and DHA to ECs. We postulate that these lipids are potentially being converted by phospholipase A2 enzymes into arachidonic acid (AA) [26], which other endothelial enzymes (i.e., lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, and epoxygenases) utilize as substrate to generate vasodilatory eicosanoids [27]. Endothelial-derived eicosanoids activate smooth muscle potassium channels, leading to cell hyperpolarization and relaxation [26].

When considering the multifactorial mechanistic complexity of RI in STEMI, an early key event that can be disrupted to attenuate the pro-inflammatory response is EC activation. The severity of endothelial injury critically depends on the early oxidative burst occurring upon reperfusion and on the acute inflammatory response characterized by adhesion of neutrophils to the endothelium [28]. RI-induced endothelial dysfunction and barrier failure are elicited by acidosis, overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide inhibition [29, 30]. The IC FNL-MLT administered at reperfusion during PCI can potentially attenuate the EC response to these pro-inflammatory stimuli and diminish microvascular dysfunction and the no-reflow phenomenon. Additionally, a growing body of evidence suggests that TLR4 and Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR2) mediate myocardial RI via nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) activation [31–35]. Activation of the NF-κB pathway via TLR4/TLR2 signaling through “danger signals” released during cell death or through ROS-associated mechanisms further propagates the pro-inflammatory and procoagulant responses [29, 36–39]. NF-κB activation induces EC adhesion molecule expression, which promotes migration of inflammatory leukocytes potentiating the RI response [29]. FNL-MLT attenuated TNF production in macrophages pulsed with the TLR4 agonist LPS, and it is possible that FNLs also attenuate the TLR4 response in ECs. Interestingly, the role of cells expressing TLR2 in mediating RI is controversial. It has been shown that TLR2 receptors in cells circulating in blood (e.g., leukocytes) appear to mediate myocardial I/RI [35]. However, studies in isolated coronary artery segments from the hearts of TLR2-deficient mice that were subjected to in vivo ischemia, but perfused in vitro (without leukocytes), had reduced endothelial dysfunction suggesting that endothelial TLR2 is involved [34]. In similar studies using postischemic isolated perfused hearts from TLR4-deficient mice (no blood components involved), NF-κB activation, myocardial pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, and myocardial dysfunction were all reduced, suggesting that TLR4 expressing cells in the heart are involved in myocardial I/RI [40, 41]. Thus, it is likely that TLR2 and TLR4 signaling in leukocytes, as well as cardiac cells including ECs, play a role in endothelial dysfunction and RI.

In the context of our FNL-MLT, high-resolution microscopy studies determined that as nanoliposomes fused with MAECs, lipids distributed into C/LR microdomains, and it is well recognized that NF-κB activation mediated by TLR2 and/or TLR4 signaling requires the assembly of functional C/LR microdomains [42–44]. Therefore, the possibility that altering the EC plasma membrane with unsaturated FNL lipids just prior to reperfusion attenuates TLR2 and TLR4 signaling and NF-κB activation by interfering with the assembly of functional C/LRs. Future studies examining the effects of FNL-MLT on TLR2 and TLR4 signaling remain to be performed. The effect of FNL-MLT on protein-lipid interactions in C/LR complexes needs to be studied, as well as its effect on the lateral movement and assembly key C/LR components into functional C/LR microdomains.

Study Limitations

The cardioprotective effect of FNL-MLT was investigated in juvenile swine, lacking co-morbidities and co-medications, which is different from the clinical situation. For proof-of-concept studies, female swine were selected because they are easier to handle than males and are the gender of choice for this model. Also, the I/RI model uses a balloon catheter for coronary occlusion and not ruptured plaque with thrombus. This limitation has consequences in the context of endothelial dysfunction and the no-reflow phenomenon since microthrombi and plaque fragments are absent. Additionally, consistency of results using this model is highly dependent on the skills and experience of the operator, and the variability in coronary anatomy between animals makes reproducible placement of balloons difficult. Lastly, in this study, FNL administration was started at 10 min prior to reperfusion, and if this MLT is to be applied clinically, the cardioprotective effect will need to be demonstrated when FNLs are administered at the start of reperfusion.

Conclusions

We conclude that FNL-MLT rapidly incorporates exogenous unsaturated lipid into cell membranes and attenuates the activation of ECs and macrophages. FNL fusion incorporates exogenous unsaturated lipid into C/LR microdomains changing their lipid composition. IC administration of FNLs just prior to reperfusion is effective in reducing myocardial IS and maybe a promising adjuvant to PCI in the treatment of STEMI.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R43HL132649) and the Kentucky Science and Technology Corporation (KSTC184–512–16–235).

Conflict of Interest Claudio Maldonado and Phillip Bauer have equity and patents and received salary from EndoProtech, Inc. Gustavo Perez-Abadia has equity and Mai-Dung Nguyen received salary from EndoProtech. Xian-Liang Tang has received grants from the company. The other authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval All applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

References

- 1.Manno S, Takakuwa Y, Mohandas N. Identification of a functional role for lipid asymmetry in biological membranes: phosphatidylserine-skeletal protein interactions modulate membrane stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(4):1943–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327(5961):46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogler O, Casas J, Capo D, Nagy T, Borchert G, Martorell G, et al. The Gbetagamma dimer drives the interaction of heterotrimeric Gi proteins with nonlamellar membrane structures. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(35):36540–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epand RM. Proteins and cholesterol-rich domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778(7–8):1576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Post JA, Ruigrok TJ, Verkleij AJ. Phospholipid reorganization and bilayer destabilization during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: a hypothesis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1988;20(Suppl 2):107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tappia PS. Phospholipid-mediated signaling systems as novel targets for treatment of heart disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85(1):25–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Paal J, Hong SH, Yusupov M, Gaur N, Oh JS, Short RD, et al. How membrane lipids influence plasma delivery of reactive oxygen species into cells and subsequent DNA damage: an experimental and computational study. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2019;21(35):19327–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escriba PV, Busquets X, Inokuchi J, Balogh G, Torok Z, Horvath I, et al. Membrane lipid therapy: modulation of the cell membrane composition and structure as a molecular base for drug discovery and new disease treatment. Prog Lipid Res. 2015;59:38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Lim EJ, Toborek M, Hennig B. The role of fatty acids and caveolin-1 in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced endothelial cell activation. Metabolism. 2008;57(10):1328–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stulnig TM, Huber J, Leitinger N, Imre EM, Angelisova P, Nowotny P, et al. Polyunsaturated eicosapentaenoic acid displaces proteins from membrane rafts by altering raft lipid composition. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(40):37335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stulnig TM, Berger M, Sigmund T, Raederstorff D, Stockinger H, Waldhausl W. Polyunsaturated fatty acids inhibit T cell signal transduction by modification of detergent-insoluble membrane domains. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(3):637–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roessler C, Kuhlmann K, Hellwing C, Leimert A, Schumann J. Impact of polyunsaturated fatty acids on miRNA profiles of monocytes/macrophages and endothelial cells-a pilot study. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fensterer TF, Keeling WB, Patibandla PK, Pushpakumar S, Perez-Abadia G, Bauer P, et al. Stabilizing endothelium of donor hearts with fusogenic liposomes reduces myocardial injury and dysfunction. J Surg Res. 2013;182(2):331–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goga L, Pushpakumar SB, Perez-Abadia G, Olson P, Anderson G, Soni CV, et al. A novel liposome-based therapy to reduce complement-mediated injury in revascularized tissues. J Surg Res. 2011;165(1):e51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ketchem CJ, Conner CD, Murray RD, DuPlessis M, Lederer ED, Wilkey D, et al. Low dose ouabain stimulates NaK ATPase alpha1 subunit association with angiotensin II type 1 receptor in renal proximal tubule cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(11): 2624–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang X, Sorkin A. Coordinated traffic of Grb2 and Ras during epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis visualized in living cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(5):1522–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones SP, Tang XL, Guo Y, Steenbergen C, Lefer DJ, Kukreja RC, et al. The NHLBI-sponsored Consortium for preclinicAl assESsment of cARdioprotective therapies (CAESAR): a new paradigm for rigorous, accurate, and reproducible evaluation of putative infarct-sparing interventions in mice, rabbits, and pigs. Circ Res. 2015;116(4):572–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinhardt CP, Dalhberg S, Tries MA, Marcel R, Leppo JA. Stable labeled microspheres to measure perfusion: validation of a neutron activation assay technique. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280(1):H108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pushpakumar SB, Perez-Abadia G, Soni C, Wan R, Todnem N, Patibandla PK, et al. Enhancing complement control on endothelial barrier reduces renal post-ischemia dysfunction. J Surg Res. 2011;170(2):e263–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reffelmann T, Kloner RA. The “no-reflow” phenomenon: basic science and clinical correlates. Heart. 2002;87(2):162–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloner RA, Dai W, Hale SL. No-reflow phenomenon. A new target for therapy of acute myocardial infarction independent of myocardial infarct size. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(3):273–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezkalla SH, Stankowski RV, Hanna J, Kloner RA. Management of no-reflow phenomenon in the catheterization laboratory. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(3):215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feher A, Chen SY, Bagi Z, Arora V. Prevention and treatment of no-reflow phenomenon by targeting the coronary microcirculation. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2014;15(1):38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uitterdijk A, Sneep S, van Duin RW, Krabbendam-Peters I, Gorsse-Bakker C, Duncker DJ, et al. Serial measurement of hFABP and high-sensitivity troponin I post-PCI in STEMI: how fast and accurate can myocardial infarct size and no-reflow be predicted? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(7):H1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols WW, Nicolini FA, Yang BC, Henson K, Stechmiller JK, Mehta JL. Adenosine protects against attenuation of flow reserve and myocardial function after coronary occlusion and reperfusion. Am Heart J. 1994;127(5):1201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astudillo AM, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. Selectivity of phospholipid hydrolysis by phospholipase A2 enzymes in activated cells leading to polyunsaturated fatty acid mobilization. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864(6):772–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giles TD, Sander GE, Nossaman BD, Kadowitz PJ. Impaired vasodilation in the pathogenesis of hypertension: focus on nitric oxide, endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factors, and prostaglandins. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(4):198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laude K, Beauchamp P, Thuillez C, Richard V. Endothelial protective effects of preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55(3): 466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Q, He GW, Underwood MJ, Yu CM. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial ischemia/reperfusion injury: perspectives and implications for postischemic myocardial protection. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(2):765–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richard V, Kaeffer N, Tron C, Thuillez C. Ischemic preconditioning protects against coronary endothelial dysfunction induced by ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1994;89(3):1254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Abarbanell AM, Herrmann JL, Weil BR, Poynter J, Manukyan MC, et al. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways and the evidence linking toll-like receptor signaling to cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Shock. 2010;34(6):548–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C, Ha T, Kelley J, Gao X, Qiu Y, Kao RL, et al. Modulating toll-like receptor mediated signaling by (1–>3)-beta-D-glucan rapidly induces cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61(3):538–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oyama J, Blais C Jr, Liu X, Pu M, Kobzik L, Kelly RA, et al. Reduced myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;109(6):784–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Favre J, Musette P, Douin-Echinard V, Laude K, Henry JP, Arnal JF, et al. Toll-like receptors 2-deficient mice are protected against postischemic coronary endothelial dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(5):1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arslan F, Smeets MB, O’Neill LA, Keogh B, McGuirk P, Timmers L, et al. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by leukocytic toll-like receptor-2 and reduced by systemic administration of a novel anti-toll-like receptor-2 antibody. Circulation. 2010;121(1):80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majkova Z, Toborek M, Hennig B. The role of caveolae in endothelial cell dysfunction with a focus on nutrition and environmental toxicants. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(10):2359–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng AM, Handa P, Tateya S, Schwartz J, Tang C, Mitra P, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I attenuates palmitate-mediated NF-kappaB activation by reducing toll-like receptor-4 recruitment into lipid rafts. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leifer CA, Medvedev AE. Molecular mechanisms of regulation of toll-like receptor signaling. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(5):927–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asehnoune K, Strassheim D, Mitra S, Kim JY, Abraham E. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2004;172(4): 2522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cha J, Wang Z, Ao L, Zou N, Dinarello CA, Banerjee A, et al. Cytokines link toll-like receptor 4 signaling to cardiac dysfunction after global myocardial ischemia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(5): 1678–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chong AJ, Shimamoto A, Hampton CR, Takayama H, Spring DJ, Rothnie CL, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury of the heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(2):170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sezgin E, Levental I, Mayor S, Eggeling C. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(6):361–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong SW, Kwon MJ, Choi AM, Kim HP, Nakahira K, Hwang DH. Fatty acids modulate toll-like receptor 4 activation through regulation of receptor dimerization and recruitment into lipid rafts in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(40):27384–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang DH, Kim JA, Lee JY. Mechanisms for the activation of Toll-like receptor 2/4 by saturated fatty acids and inhibition by docosahexaenoic acid. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;785:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]