Abstract

Introduction:

Intubations are frequently performed procedures in Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) and delivery rooms (DR). Unsuccessful first attempts are common as are tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) and severe desaturations. Stylets are often used during intubation, but their association with intubation outcomes is unclear.

Objective:

To compare intubation success, rate of relevant TIAEs, and severe desaturations in neonates intubated with and without stylets.

Methods:

Tracheal intubations of neonates in the NICU or DR from 16 centers between October 2014 and December 2018, performed by neonatology or pediatric providers, were collected from the NEAR4NEOs international registry. Primary oral intubations with a laryngoscope were included in the analysis. First attempt success, the occurrence of relevant TIAEs, and severe oxygen desaturation (≥20% saturation drop from baseline) were compared between intubations performed with versus without a stylet. Logistic regression with generalized estimate equations was used to control for covariates and clustering by sites.

Results:

Out of 5,292 primary oral intubations, 3,877 (73%) utilized stylets. Stylet use varied considerably across the centers with a range between 0.5-100%. Stylet use was not associated with first attempt intubation success, esophageal intubation, mainstem intubation, or severe desaturations after controlling for confounders. Patient size was associated with these outcomes and much more predictive of success.

Conclusions:

Stylet use during neonatal intubation was not associated with higher first attempt intubation success, fewer relevant TIAEs, or less severe desaturations. These data suggest that stylets can be used based on individual preference, but stylet use may not be associated with better intubation outcomes.

Keywords: Neonatal Intubation, Stylet, TIAE, airway injury, difficult airway

INTRODUCTION:

Intubations are frequently performed procedures in Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) and delivery rooms (DR). Unsuccessful first intubation attempts are common as are adverse tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) and severe desaturations.[1,2] Successful first attempt neonatal intubations are associated with fewer TIAEs and improved neonatal and pediatric outcomes.[1-4] Stylets are commonly used in an attempt to improve intubation success. A stylet is a malleable metal wire coated in plastic which can be inserted into the lumen of an endotracheal tube (ETT) with the intent of providing rigidity to the ETT to assist in passing it through the vocal cords during endotracheal intubation.[5] Current Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) guidelines do not recommend routine use of a stylet for endotracheal intubation.[6] However, in a national survey of neonatal airway providers, the majority reported using a stylet with most or all of their intubations based on the belief that stylet use improved intubation success rates.[7]

Despite their common use, there is limited evidence investigating the effects of stylet use on neonatal intubation outcomes.[8] In the only small randomized trial investigating stylets in neonatal intubations, trainees were randomized to either use a stylet or intubate without a stylet on their first attempt. This study found stylets did not affect first attempt intubation success rates or upper airway trauma [8]

The use of a stylet in an ETT presents potential risks. There are numerous case reports of stylet related adverse outcomes including torn or perforated airways and retained broken stylet pieces.[9-13] In a national survey of neonatal airway providers, 78% had experienced or witnessed an adverse event resulting from stylet use with the most common issue being accidental dislodgement of the ETT during stylet removal necessitating yet another intubation to secure an airway. However, 71% of respondents felt stylets were “generally safe.”[7]

Severe oxygen desaturation, defined as a decrease of at least 20% from baseline, is common during neonatal intubation. [1, 2] Severe desaturations have been shown in a multi-center study to occur in 48% of intubations performed in the NICU and 31% of intubations performed in the DR.[1] One proposed potential benefit for using stylets during intubation is a decrease in the time to achieving successful ETT placement. If stylets facilitate ease of ETT placement, they could theoretically reduce intubation time and thus decrease the frequency of desaturation events.

The goal of this study was to examine associations between stylet use during neonatal intubation with intubation success, adverse events, and severe desaturations using a prospectively collected large quality improvement research database. We hypothesized that stylet use during intubation would be associated with improved first attempt success rates, fewer severe desaturations, but an increased incidence of relevant TIAEs such as airway injury.

METHODS:

Setting:

This study uses data collected from 16 academic neonatal intensive care units.[1]

Design:

Data were extracted from the NEAR4NEOs database, a multi-site international collaborative that prospectively collects information on all intubations occurring within the NICU and DR for participating sites.[1] All tracheal intubation (TI) events performed by direct or video laryngoscopy in the NICU or DR in the NEAR4NEOS database between Oct 2014-Dec 2018 were included. Data were collected at each institution on a standardized form following collaborative operational definitions, deidentified and verified for completeness and accuracy by a designated and trained study personnel, and entered into a centralized online secure database, REDCap. The institutional review board at each participating site either approved the study with a waiver of informed consent for the use of patient data.

Definitions:

First attempt intubation success was defined as placement of an ETT in the trachea by the first airway provider on their initial attempt. An intubation course was defined as all the intubation attempts performed on the same patient on a given date with one course of medications and one intubation method. Patient demographics included weight at the time of intubation, birth and corrected gestational age, and comorbidities. Intubation demographics included the indication, airway device utilized, medications administered, and the first attempt provider’s discipline. Intubations occurring outside of the NICU or DR, intubations via the nasal route, and those in which the ETT was exchanged were excluded. Intubations performed by non-neonatology and non-general pediatric providers, such as anesthesia providers, were excluded. Stylet use was counted only if utilized on the first attempt. Stylet use was at the discretion of the provider and/or unit practice.

Adverse TIAEs relevant to stylet use included airway injury, esophageal intubation with immediate or delayed recognition, mainstem intubation confirmed on x-ray, and pneumothorax related to the intubation attempt as determined by the clinical team. Airway injury was defined as any damage to the upper or lower airway and included lacerations, abrasions, perforations. Severe oxygen desaturations were defined as a decrease of 20% or more from the pre-intubation baseline oxygen saturation.

Outcome measures:

The primary outcome was first attempt success. Secondary outcomes included the adverse TIAEs relevant to stylets: airway injury, esophageal intubation, mainstem bronchial intubation, and pneumothorax as well as oxygen desaturation ≥20%.[1]

Statistics:

A priori power calculation was performed with simulation. To detect a clinically meaningful difference of 10% (first attempt success 60% with stylet use and 50% without stylet use) with the variance of center level random effect =0.287, the power was estimated as >99%. The variance of center level random effect was assumed based on the use of stylet in the current dataset.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to present the demographic data as number and percentages for categorical variables and as medians and interquartile ranges for nonparametric, continuous data. The relationships between patient, provider, and practice characteristics with the occurrence of stylet use were analyzed using univariable analysis with Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test for dichotomous variables or Wilcoxon rank-sum for numeric variables. The clinical impact of stylet use was assessed by univariate analysis with the occurrence of pre-specified tracheal intubation associated events: TIAEs (airway injury, esophageal intubation, mainstem intubation, pneumothorax) and severe oxygen desaturation. The independent effect of stylet use on first attempt success rate (primary outcome) and secondary outcomes of specific TIAEs and severe oxygen desaturation was determined by generalized estimate equation (GEE) multivariable logistic regression model while controlling for patient, provider, and practice factors. Intra-site association of outcomes was accounted for by fitting exchangeable correlation structures in the GEE models, with robust standard errors based on the “sandwich” covariance matrix. Covariates were included in the multivariable model when there was an association with stylet use at p < 0.05 in the univariable analysis.

RESULTS:

Demographics and factors associated with stylet use

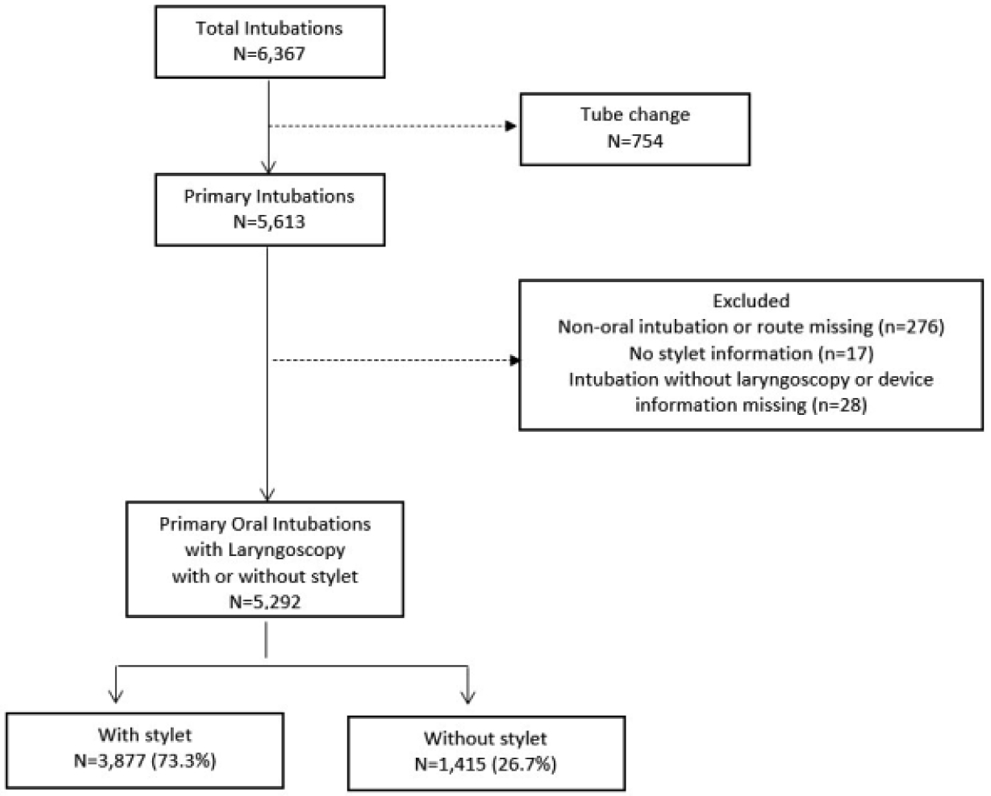

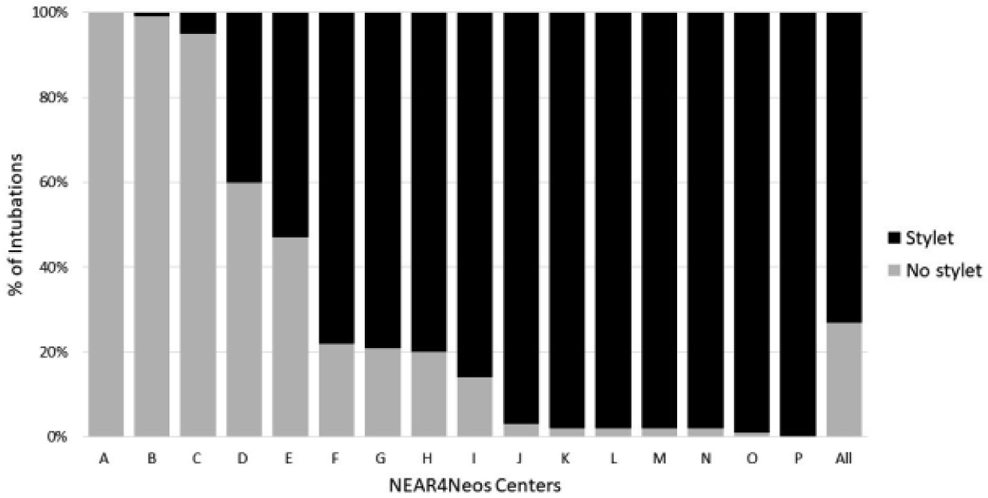

Out of 5,292 primary oral intubations from 16 institutions, 3,877 (73%) utilized a stylet (Figure 1). Stylet use varied considerably across the centers with a range of 0.5-100% (Figure 2). Stylet use varied by many patient factors (Table 1). There was no difference in stylet use between NICU and DR. A stylet was used more often in lower weight infants and at a younger age. Stylets were used more often in infants with acute respiratory failure. Stylets were used less often in infants with congenital anomalies and neurologic diagnoses. Stylets were more often used during intubations for oxygen failure, surfactant administration, and DR resuscitations. Intubations for ventilation failure, procuedures, and replacement of endotracheal tubes after unplanned extubations more often performed without stylets. Among intubations with stylet, neonatology fellows were more likely the first attempt providers, while intubations without stylets more often had nurse practitioners (NP), physician assistants (PA), and hospitalists as the first attempt providers. Sedation and paralysis were less often used in the stylet group. Video laryngoscopy was less often used in the stylet group.

Figure 1.

Study Enrollment Diagram

Figure 2.

Use of Stylets for Intubation by NEAR4NEOS Center

Table 1.

Patient, Provider, and Practice Characteristics among tracheal intubations with vs. without stylet use

| Patient characteristics N=5,292 |

Stylet n=3,877 |

Without Stylet n=1,415 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current weight, g, median (IQR) | 1,500 (890-2780) | 2,060 (1000-3100) | <0.0001 |

| Birth gestational age, weeks, median (IQR) | 28 (25-35) | 30 (26-36) | <0.0001 |

| Age at time of intubation, days, median (IQR) | 1 (0-22) | 4 (0-42) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Acute Respiratory Failure | 2,557 (66.0%) | 805 (56.9%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Respiratory Failure | 648 (16.7%) | 222 (15.7%) | 0.373 |

| Congenital anomaly requiring surgery | 355 (9.2%) | 212 (15.0%) | <0.001 |

| Congenital heart disease | 235 (6.1%) | 132 (9.3%) | <0.001 |

| Neurologic impairment | 211 (5.4%) | 98 (6.9%) | 0.042 |

| Sepsis | 177 (4.6%) | 71 (5.0%) | 0.491 |

| Airway/Craniofacial anomaly | 171 (4.4%) | 78 (5.5%) | 0.094 |

| Acquired surgical condition | 120 (3.1%) | 27 (1.9%) | 0.020 |

| Intubation Indications | |||

| Oxygenation failure | 1,115 (28.8%) | 354 (25.0%) | 0.007 |

| Ventilation failure | 1,051 (27.1%) | 446 (31.5%) | 0.002 |

| Apnea & Bradycardia | 637 (16.5%) | 213 (15.1%) | 0.227 |

| Surfactant administration | 1,030 (26.6%) | 229 (16.2%) | <0.001 |

| Delivery room clinical indication | 814 (21.0%) | 234 (16.5%) | <0.001 |

| Procedure | 271 (7.0%) | 157 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Unplanned extubation | 323 (8.3%) | 154 (10.9%) | 0.004 |

| Upper Airway Obstruction | 157 (4.1%) | 45 (3.2%) | 0.144 |

| Shock | 107 (2.8%) | 33 (2.3%) | 0.391 |

| First attempt provider | <0.001 | ||

| Pediatric resident | 553 (14.3%) | 185 (13.1%) | |

| Neonatology fellow | 1,423 (36.7%) | 467 (33.0%) | |

| Neonatology attending | 166 (4.3%) | 114 (8.1%) | |

| Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant/Hospitalist | 1,327 (34.2%) | 547 (38.7%) | |

| Respiratory therapist (RT) | 249 (6.4%) | 16 (1.1%) | |

| Other (subspecialists) | 157 (4.1%) | 86 (6.1%) | |

| Location, Delivery Room (DR) | 1,039 (26.8%) | 368 (26.0%) | 0.564 |

| Vagolytic use | 1,550 (40.0%) | 758 (53.6%) | <0.001 |

| Premedication use | <0.001 | ||

| No sedation or paralysis | 1,945 (50.2%) | 513 (36.3%) | |

| Sedation only | 602 (15.5%) | 120 (8.5%) | |

| Sedation and paralysis | 1,315 (33.9%) | 776 (54.8%) | |

| Paralysis only | 15 (0.4%) | 6 (0.4%) | |

| Video Laryngoscopy | 760 (19.6%) | 468 (33.1%) | <0.001 |

Stylet use and outcomes

The first attempt success rate was lower in the stylet group in the univariate analysis: 47.7% vs. 51.0%, p=0.03. Stylet use was not associated with first attempt success (adjusted odds ratio 1.12, 95% Confidence Interval 0.68-1.85, p=0.664) after controlling for differences in patient, practice, and provider factors and clustering for study site, Table 2. First attempt success was more likely to occur in infants who weighed >1,5kg, in intubations utilizing both sedative and paralytic medications, and in intubations performed by non-residents.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of association of stylet use with first attempt success

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stylet use | 1.12 | 0.68-1.85 | 0.664 |

| Current weight >1.5kg | 1.37 | 1.13-1.67 | 0.002 |

| Birth Gestational Age ≥28weeks | 1.14 | 0.93-1.41 | 0.206 |

| Intubation after 1st day of life | 0.97 | 0.74-1.28 | 0.837 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Congenital heart disease | 0.93 | 0.76-1.14 | 0.461 |

| Congenital anomaly requiring surgery | 1.00 | 0.81-1.22 | 0.977 |

| Neurologic impairment | 0.95 | 0.76-1.20 | 0.675 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 1.05 | 0.96-1.15 | 0.302 |

| Surgery for acquired disorder | 0.78 | 0.39-1.54 | 0.472 |

| Indication for intubation | |||

| Oxygen failure | 1.08 | 0.89-1.30 | 0.422 |

| Procedure | 1.18 | 0.93-1.50 | 0.177 |

| Ventilation failure | 0.92 | 0.78-1.08 | 0.304 |

| Surfactant administration | 0.88 | 0.77-1.01 | 0.063 |

| Unplanned extubation | 1.43 | 1.00-2.06 | 0.051 |

| Diagnosis requiring intubation in DR | 1.02 | 0.81-1.29 | 0.847 |

| First attempt provider* | |||

| Resident | Reference | ||

| Fellow | 3.10 | 2.33-4.11 | <0.001 |

| Neonatology attending | 5.16 | 3.14-8.50 | <0.001 |

| Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant/Hospitalist | 2.64 | 1.89-3.67 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Therapist (RT) | 2.73 | 1.79-4.15 | <0.001 |

| Other (subspecialist) | 2.55 | 1.81-3.59 | <0.001 |

| Vagolytic use♯ | 1.10 | 0.92-1.31 | 0.296 |

| Premedication | |||

| No sedative or paralytic | Reference | ||

| Sedative only | 0.60 | 0.45-0.79 | <0.001 |

| Sedative and paralytic | 1.49 | 1.12-2.03 | 0.009 |

| Paralysis only | 0.87 | 0.26-2.93 | 0.823 |

| Video laryngoscopyΛ | 1.20 | 0.86-1.68 | 0.276 |

Vagolytic includes atropine.

Reference is Direct laryngoscopy

Unadjusted analysis of relevant TIAEs showed significantly more esophageal intubations, mainstem bronchial intubations, and oxygen desaturation (≥20%) in the stylet group (Table 3). Multivariate analysis of other TIAEs and oxygen desaturation did not reveal significant independent association with stylets (all p>0.05).

Table 3.

The association of stylet use and adverse outcomes

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis (compared to without stylet) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stylet n (%) |

Without stylet n (%) |

p-value | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) |

p-value | |

| Airway injury | 21 (0.5%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0.058 | Not performed | N/A |

| Esophageal intubation | 469 (12.1%) | 108 (7.6%) | <0.001 | 1.29 (0.83-2.02) | 0.251 |

| Mainstem bronchial intubation | 76 (2.0%) | 15 (1.1%) | 0.026 | 1.44 (0.62-3.34) | 0.397 |

| Pneumothorax | 15 (0.4%) | 3 (0.2%) | 0.431 | Not performed | N/A |

| Oxygen Desaturation ≥20% | 1,714 (49.5%) | 595 (45.3%) | 0.010 | 1.11 (0.85-1.46) | 0.438 |

Multivariable analyses utilized logistic regression to control for the patient, provider, and practice characteristics associated with the use of stylet and clustering by sites. Refer to Method section for details. N/A: not applicable.

Airway injury cases

The cases with airway injury (n=23) were of lower weight [median current weight 1,110g (IQR:815-1,880) vs. median 1,640g (IQR:920-2,900) for infants without airway injuries] with a higher proportion of airway/craniofacial anomaly (21.7% vs. 4.6%,p=0.004), Table 4. There was a 5-fold difference in airway injury rates when stylets were used (n-21, 0.5% with stylets vs. n=2, 0.1% without stylets) that did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06), Table 3.

Table 4.

Airway injury cases (N=23)

| Patient characteristics | Stylet n=21 |

Without Stylet n=2 |

Total N=23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current weight, g, median (IQR) | 1,140 (900-1,880) | 580 (560-600) | 1,110 (815-1,880) |

| Birth gestational age, weeks, median (IQR) | 27 (25-32) | 23.5 (23-24) | 27 (24-32) |

| Age at time of intubation, days, median (IQR) | 7 (0-18) | 1 (0-2) | 2 (0-18) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Airway/Craniofacial anomaly | 5 (23.8%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Acquired surgical condition | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.4%) |

| Intubation Indications, n (%) | |||

| Oxygenation failure | 9 (42.9%) | 2 (100%) | 11 (47.8%) |

| Ventilation failure | 6 (28.6%) | 1 (50.0%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Surfactant administration | 5 (23.8%) | 1 (50.0%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| Delivery room clinical indication | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (50.0%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Unplanned extubation | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.4%) |

| Upper Airway Obstruction | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Shock | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| First attempt provider, n (%) | |||

| Pediatric resident | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13.4%) |

| Neonatology fellow | 10 (47.6%) | 2 (100%) | 12 (52.7%) |

| Neonatology attending | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.4%) |

| Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant/Hospitalist | 5 (23.8%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Respiratory therapist (RT) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Other (subspecialists) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Location, Delivery Room (DR), n (%) | 2 (9.5%) | 1 (50.0%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Premedication use, n (%) | |||

| No sedation or paralysis | 7 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | 8 (34.8%) |

| Sedation only | 7 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Sedation and paralysis | 7 (33.3%) | 1 (50.0%) | 8 (34.8%) |

| Paralysis only | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Video Laryngoscopy, n (%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (13.0%) |

Discussion:

We examined associations between stylet use during neonatal intubation with intubation success, adverse events, and severe desaturations. In this large sample of infant intubations, we found that even though stylets were used in nearly 75% of intubation attempts, there was significant variation with some centers using them nearly universally, and others almost never. While stylet use varied considerably between patients and providers, stylet use was not associated with first attempt intubation success, adverse events, or severe desaturations after controlling for patient, provider, and practice factors and clustering by site. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the largest study to date examining the associations of stylet use and neonatal intubation outcomes.

We did not find an association between stylet use and first attempt intubation success, which is consistent with prior studies. In the only published randomized control trial of stylets for neonatal intubation, there was no association with success but the overall trial was small (n=232) and occurred at a single center.[8] Despite the current practice of frequent stylet utilization, the NRP does not recommend routine use of stylets and there is little data to support the use of stylets during neonatal intubation.[6] The reasons for their popularity could lie in the perceived value of the stiffness of the ETT, or in intubation training itself, with comfort and belief of presumed efficacy passed from one generation of providers to the next. Comfort with a particular stiffness or bend in the ETT may make intubating without a stylet feel different and unfamiliar, leaving the laryngoscopist feeling less confident or safe in their procedural ability. As this study allowed each laryngoscopist and site to choose whether they used a stylet, the impact of individual laryngoscopist’s performance with and without a stylet could not be evaluated.

We found an increased number of airway injury when stylets were used, however, the reported number of airway injury cases were small and the detailed description of the events were not reported. This makes the analysis less informative than desired. The cases with airway injury were of lower weight and had higher proportion of airway/craniofacial anomaly. Multivariate analysis did not show an independent significant association between stylet use and the relevant TIAEs often described in the literature. As the case reports in the literature described, there remain some potential risks involved with stylet use. [9-13] Tracheal perforations are extremely rare events and might require case-control studies to evaluate their relationship with stylets, but the overall low number of airway injuries in this large data set provide some reassurance that these are uncommon outcomes, occurring in less than 1% of intubations.[7] However, there remains some potential risks involved in their use. There is significant variation in how providers place stylets within ETTs with some placing the stylet more distal or at the level of the Murphy eye to facilitate increased tube stiffness.[14] This practice may potentially increase the risk of the stylet tip positioned beyond the tip of the ETT and injure delicate airway tissue or break off. There are numerous case reports describing airway or ETT obstruction caused by the retained plastic sheath from a stylet and endoscopic removal of retained stylet components can be especially difficult in premature neonates with small airways.[9-13] Many laryngoscopists bend the ETT and stylet complex which may increase the risk of shearing of the plastic coating resulting in retained stylet components. There is a need to train clinical staff on a standardized placement of the tip of the stylet within the ETT to minimize the risk of perforations and breakage.

In this study, stylet use was not associated with severe desaturations. Infants with significant respiratory system compromise are most at risk for severe desaturation during intubation attempts due to their poor respiratory reserve. A longer duration of intubation is likely to result in more severe desaturation. Stylet use is often believed to shorten intubation attempts, which would result in fewer severe desaturation events. Unfortunately, the NEAR4NEOS database does not include intubation duration as a metric, so we are unable to report on the impact that stylet use has on the duration of intubation. Since stylet use was not associated with a difference in odds of severe desaturation in multivariate analysis, we speculate the overall impact of stylet use on intubation duration may be small.

Currently, neonatologists routinely use conventional stylets consisting of a metal wire covered in a plastic sheath. However, there are reports in the otolaryngology and anesthesia literature of alternative stylets. Stylets with built-in cameras are utilized by otolaryngologists to facilitate intubation of patients with difficult airways. Anesthesia literature has also investigated the use of light wands, a type of lighted stylet, in children undergoing elective surgery.[15] There is room for innovation regarding alternative stylets designed specifically for the neonatal population.

This study has some limitations. While the data is prospectively collected, the stylet use was not randomized.A larger proportion of intubation with stylets are attempted by trainees (51% done by residents or fellows) compared to intubations without stylets (46% attempted by residents or fellows), potentially influencing success rates and adverse TIAEs. Sedation and paralysis were used together more often in intubations without stylets and their use was associated with a higher first attempt success rate in the multivariable analysis, as reported before.[16] Similarly the stylet use was more common in an anticipated difficult airway in some situation. It is also possible that providers reported more airway injuries when a stylet was used during intubation, which may have been due to an ascertainment or reporting bias. An additional limitation is that the severity of airway injuries were not captured on the data collection form, making the interpretation of the potential airway harm difficult. Despite these limitations, this is one of the largest studies investigating the use of stylets for infant intubations and provides valuable data on a diverse neonatal population in the NICU and DR.

Conclusions:

For intubations in the NICU and DR, stylet use was not associated with a higher first attempt success rate. Stylet use was highly variable across the institutions. Stylet use was not associated with relevant adverse events (airway injury, esophageal intubation, mainstem bronchial intubation, and pneumothorax). Consideration should be used when deciding whether to use a stylet during neonatal intubation given the potential risk of injuries associated with stylet use. Further studies may address the effectiveness of stylet use in both intubation success and adverse events using a pragmatic randomized control design.

Acknowledgement:

This project would like to acknowledge the National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates: NEAR4NEOS Investigators.

Sources of funding:

This project was supported by NICHD R21HD089151. Drs. Sawyer, Ades and Nishisaki was supported by NICHD R21HD089151. Dr. Nadkarni was supported by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Endowed Chair in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine.

Abbreviations:

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- DR

Delivery Room

- TIAE

Tracheal Intubaiton Associated Events

- NEAR4NEOS

National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates

- ETT

Endotracheal Tube

- IQR

Intraquartile Range

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics: This study was granted ethics exemptions from written consent due to the deidentified nature of this QI data by each of the 16 contributing sites’ Ethical Review Boards. This is included in the methods section as such: “The institutional review board at each participating site approved the study with a waiver of informed consent for the use of patient data.”

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Megan M. Gray, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Jennifer A. Rumpel, Department of Pediatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and Arkansas Children’s Research Institute, Little Rock, AR.

Brianna K. Brei, Department of Pediatrics, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Jeanne Alexandra Krick, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA.

Taylor Sawyer, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Kristen Glass, Penn State College of Medicine, Penn State Health, Hershey, PA.

Stephen DeMeo, Division of Neonatology, WakeMed Health and Hospitals, Raleigh, North Carolina.

James Barry, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Neonatology, Aurora, Colorado.

Anne Ades, Department of Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Natalie Napolitano, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Lindsay Johnston, Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, New Haven, CT.

Ahmed Moussa, Department of Pediatrics, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Phillip Jung, Department of Pediatrics, Universitaetsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Luebeck, Luebeck, GERMANY.

Bin Huey Quek, Neonatology, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore, SINGAPORE.

Ayman Abou Mehrem, Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, CANADA.

Jeanne Zenge, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Neonatology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO.

Justine Shults, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Ambler, Pennsylvania.

Vinay Nadkarni, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care, and Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Jae Kim, Perinatal Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Neetu Singh, Pediatrics, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical center, Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Alicia Tisnic, Alberta Children's Hospital, Alberta, Alberta, CANADA.

Elizabeth Foglia, Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Akira Nishisaki, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care, and Pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

References:

- [1].Foglia EE, Ades A, Sawyer T, Glass KM, Singh N, Jung P, et al. Neonatal Intubation Practice and Outcomes: An International Registry Study. Pediatrics 2019January;143(1): 10.1542/peds.2018-0902. Epub 2018 Dec 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Foglia EE, Ades A, Napolitano N, Leffelman J, Nadkarni V, Nishisaki A. Factors Associated with Adverse Events during Tracheal Intubation in the NICU. Neonatology 2015;108(1):23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sauer CW, Kong JY, Vaucher YE, Finer N, Proudfoot JA, Boutin MA, et al. Intubation Attempts Increase the Risk for Severe Intraventricular Hemorrhage in Preterm Infants-A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pediatr 2016October;177:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lee JH, Turner DA, Kamat P, Nett S, Shults J, Nadkarni VM, et al. The number of tracheal intubation attempts matters! A prospective multi-institutional pediatric observational study. BMC Pediatr 2016April29;16:58-016-0593-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].O'Shea JE, O'Gorman J, Gupta A, Sinhal S, Foster JP, O'Connell LA, et al. Orotracheal intubation in infants performed with a stylet versus without a stylet. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017June22;6:CD011791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation (NRP). 7th Edition ed. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gray MM, Umoren RA, Harris S, Strandjord TP, Sawyer T. Use and perceived safety of stylets for neonatal endotracheal intubation: a national survey. J Perinatol 2018October;38(10):1331–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kamlin CO, O'Connell LA, Morley CJ, Dawson JA, Donath SM, O'Donnell CP, et al. A randomized trial of stylets for intubating newborn infants. Pediatrics 2013January;131(1):e198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chiou HL, Diaz R, Orlino E Jr, Poulain FR. Acute airway obstruction by a sheared endotracheal intubation stylet sheath in a premature infant. J Perinatol 2007November;27(11):727–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Das A, Chagalamarri S, Saridakis K. Partial Obstruction of the Endotracheal Tube by the Plastic Coating Sheared from a Stylet. Case Rep Pediatr 2016;2016:4373207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Koodiyedath B, Tyler W, Deshpande SA, Parikh D. Endobronchial obstruction from an intubation stylet sheath. Neonatology 2008;94(4):304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shetty S, Power S, Afshar K. A sheared stylet. BMJ Case Rep 2010July15;2010: 10.1136/bcr.02.2010.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Viswanathan S, Rodriguez Prado Y, Chua C, Calhoun DA. Extremely Preterm Neonate with a Tracheobronchial Foreign Body: A Case Report. Cureus 2020April13;12(4):e7659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Forestner JE. Frank J. Murphy, M.D., C.M., 1900-1972: his life, career, and the Murphy eye. Anesthesiology 2010November;113(5):1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fisher QA, Tunkel DE. Lightwand intubation of infants and children. J Clin Anesth 1997June;9(4):275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ozawa Y, Ades A, Foglia EE, DeMeo S, Barry J, Sawyer T, et al. ; National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates (NEAR4NEOS) Investigators. Premedication with neuromuscular blockade and sedation during neonatal intubation is associated with fewer adverse events. J Perinatol. 2019June;39(6):848–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]