Abstract

Background:

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is an atypical variant of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) that presents with visuospatial/perceptual deficits. PCA is characterized by atrophy in posterior brain regions which overlaps with atrophy occurring in logopenic primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA), another atypical AD variant characterized by language difficulties, including phonological errors. Language abnormalities have been observed in PCA, although the prevalence of phonological errors is unknown. We aimed to compare the frequency and severity of phonological errors in PCA and lvPPA, and determine the neuroanatomical correlates of phonologic errors and language abnormalities in PCA.

Methods:

The presence and number of phonological errors was recorded during the Boston Naming Test and Western Aphasia Battery repetition subtest in 27 PCA patients and 27 age and disease duration-matched lvPPA patients. Number of phonological errors, and scores from language tests, were correlated with regional grey matter volumes using Spearman correlations.

Results:

Phonological errors were evident in 55% of PCA patients and 70% of lvPPA patients, with lvPPA having higher average number of errors. Phonological errors in PCA correlated with decreased left inferior parietal and lateral temporal volume. Naming and fluency were also associated with decreased left lateral temporal lobe volume.

Conclusions:

Phonological errors are common in PCA, although they are not as prevalent or severe as in lvPPA, and they are related to involvement of left temporoparietal cortex. This highlights the broad spectrum of clinical symptoms associated with AD and overlap between PCA and lvPPA.

Keywords: Language, phonological errors, logopenic, MRI, atypical Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by decline in visuospatial and visuoperceptual skills[1-4] that impact activities of daily living[5]. These deficits are often accompanied by some or all features of Balint’s or Gerstmann’s syndromes, including optic ataxia, oculomotor apraxia, alexia, dysgraphia or agraphia, finger agnosia, and left-right disorientation[1, 6, 2-4]. Most patients with PCA have Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at autopsy and, hence, PCA is often considered an atypical variant of AD. Neuroimaging studies have shown that PCA is associated with brain atrophy, hypometabolism and tau uptake on positron emission tomography (PET) in the parieto-occipital and posterior temporal regions, as well as language associated areas such as the angular and supramarginal gyri[7-9]. Atrophy tends to involve both hemispheres but often affects the right more than the left[7]. The primary regions of neurodegeneration in PCA are distinct but overlap significantly with those of another atypical AD variant, the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA)[10] which shows involvement of left lateral temporoparietal cortices[11-14].

The clinical presentation of lvPPA differs from PCA, as it is characterized by progressively worsening language difficulties, including difficulties with single-word retrieval and phrase and sentence repetition[15, 16, 10, 17]. In addition, although phonological errors are not required for a diagnosis of lvPPA, the majority of descriptions include phonological errors as a primary characteristic of this disorder[15, 18-20]. Phonological errors consist of the omission, addition, substitution, and metathesis (switching, transposition) of phonemes (discrete sound units) that are not distorted in production[11, 21, 20]. Phonological errors in lvPPA have been associated with degeneration of the left inferior parietal and supramarginal gyri[22], regions affected in PCA and lvPPA.

A few studies have mentioned impaired language abilities in PCA[23-25]. Two of the earliest descriptions of PCA describe these language impairments as ‘transcortical sensory aphasia’ that develop with disease progression, with patients having difficulty with word-finding (anomia) and some additional deficits in speech comprehension[1, 23]. More recently, studies have shown that anomia is quite prominent in PCA patients, along with other language deficits that are typical of the lvPPA-like difficulties with phrase or sentence repetitions[24, 25]. Phonological errors in reading have been observed in one patient[26]. In fact, PCA patients can have all of the clinical features of lvPPA[27]. Little, however, is known about phonological errors in PCA, including how commonly they occur and whether they relate to degeneration of specific brain regions.

We aimed to determine the frequency and neuroanatomical correlates of phonological errors in PCA, as well as the neuroanatomical correlates of other language deficits in PCA. A better understanding of language abnormalities in PCA is important for improved characterization of this syndrome and the clinical heterogeneity present in AD. Our hypothesis was that phonologic errors would be observed in PCA patients and would be associated with atrophy of the posterior temporal and inferior parietal regions.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Twenty-seven PCA participants were recruited by the Neurodegenerative Research Group (NRG) from the Mayo Clinic Department of Neurology into an Alzheimer’s Association funded study between March 2013 and March 2015. All participants met clinical criteria for PCA[28] and underwent detailed neurological (KAJ) and neuropsychological evaluations, as well as volumetric MRI and beta-amyloid PET using Pittsburgh Compound B. The Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) fluency and repetition subtests[29], and the 15-item Boston Naming Test (BNT)[30] were audio recorded and used to assess language function. All PCA patients were classified as amyloid-positive on PET based on criteria previously described[31].

The 27 PCA participants were matched by age and disease duration to 27 lvPPA participants who were also recruited by NRG. All underwent speech-language evaluation by a speech-language pathologist (JRD or EAS) and met clinical criteria for lvPPA[10]. The speech-language evaluation included the WAB and the BNT, and video recordings were obtained of the entire speech-language evaluation. A thorough neurological (KAJ) and neuropsychological battery was also performed. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic IRB and all patients provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Phonological error analysis

Speech responses during the BNT and the WAB repetition task were evaluated for phonological errors by a trained phonetician (KAT) for the 54 PCA and lvPPA patients. These tasks were chosen for evaluation of phonological errors because it has been previously shown that phonological errors typically occur most frequently during repetition and naming tasks[15, 32, 21, 33, 20]. This evaluation was done offline based on the audio/video recordings that were made at the time of testing. Phonological errors were defined as above, by any phoneme omission, addition, substitution, or transposition, following the methods set forth by Petroi et al. [20]. They were transcribed using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)[34]. Phonological errors that were later repaired were still included as errors. The total number of phonological errors for each participant was summed across the two tasks.

MRI analysis

All participants underwent a 3T head MRI protocol that included a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR/TE/TI, 2300/3/900ms; flip angle 8°, 26-cm field of view (FOV); 256×256 in-plane matrix with a phase FOV=0.94, slice thickness=1.2 mm). Regional grey matter volumes were calculated for left and right lateral temporal lobe (inferior+middle+superior temporal gyri), inferior parietal lobe, superior parietal lobe, supramarginal gyrus, angular gyrus, and occipital lobe (inferior occipital, middle occipital, superior occipital, lingual, and cuneus regions) using the Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT) (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/) atlases. These regions were selected because they are typically atrophic in PCA and have been implicated in phonological errors in lvPPA[22]. The MCALT atlases were propagated to the native MPRAGE space using ANTs. Tissue probabilities were determined for each MPRAGE using Unified Segmentation in SPM12, with MCALT tissue priors and settings. Total intracranial volume (TIV) was also calculated and all regional volumes were divided by TIV to correct for variations in head size.

Statistics

All statistics were performed in R[35] using the integrated development environment RStudio[36]. Two sample t-tests were used to compare PCA and lvPPA across variables; p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Spearman rank correlations were performed to assess correlations between regional volumes and phonological errors, WAB fluency, BNT, and WAB repetition scores in the PCA group. P-values were, again, corrected for multiple comparisons using FDR correction.

Results

Demographics

PCA and lvPPA did not differ in age, sex, disease duration, or frequency of phonological errors (Table 1). The lvPPA participants performed significantly worse on BNT, WAB repetition, WAB fluency, and had a greater number of total phonological errors. The PCA patients performed worse on visuospatial/perceptual tests.

Table 1:

Demographic and language measures in PCA and lvPPA

| PCA | lvPPA | p-value | FDR corrected p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at assessment, years | 64 (58, 70) | 68 (62, 72) | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Gender (% female) | 48% | 38% | 0.49 | 0.49 |

| Disease duration, years | 4 (3, 7) | 4 (3, 5) | 0.1 | 0.14 |

| Phonological errors (yes/no) | 55% | 70% | 0.2 | 0.24 |

| BNT (/15) | 13 (11, 14) | 7 (4.25, 11.75) | 0.00005 | 0.0002 |

| WAB repetition (/100) | 92 (90, 98) | 77 (66.5, 88.5) | 0.00004 | 0.0002 |

| Fluency score (/10) | 10 (9, 10) | 8 (6.5, 8.75) | 0.00001 | 0.0001 |

| Number of phonological errors | 2 (1, 3) | 5 (2, 6.5) | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| MoCA, /30 | 20 (12, 21) | 17 (10.5, 20) | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| CDR sum of boxes, /18 | 3 (2, 6.75) | 3 (1.5, 4) | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| VOSP cubes, /10 | 2 (1, 5) | 8.5 (5.25, 10) | 0.0004 | 0.001 |

| VOSP letters, /20 | 12 (5.5, 16) | 19 (18, 20) | 0.001 | 0.002 |

Data shown as median (inter-quartile range). BNT – Boston Naming Test; WAB – Western Aphasia Battery; MoCA – Montreal Cognitive Assessment; CDR – Clinical Dementia Rating; VOSP – Visual Object and Space Perception

Neuroimaging

PCA showed greater atrophy than lvPPA throughout the right hemisphere, particularly in superior and inferior parietal, angular, supramarginal, temporal, and occipital regions (Table 2). PCA also showed decreased cortical volumes in left superior parietal and occipital regions compared to lvPPA.

Table 2:

Regional grey matter volumes in PCA and lvPPA

| Region of Interest | PCA | lvPPA | p-value | FDR corrected |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior Parietal | L | 0.14 (0.12, 0.15) | 0.13 (0.11, 0.16) | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| R | 0.17 (0.14, 0.19) | 0.21 (0.19, 0.23) | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Superior Parietal | L | 0.30 (0.27, 0.33) | 0.38 (0.32, 0.40) | 0.008 | 0.01 |

| R | 0.27 (0.25, 0.30) | 0.36 (0.31, 0.39) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Angular Gyrus | L | 0.21 (0.16, 0.26) | 0.21 (0.18, 0.25) | 0.47 | 0.54 |

| R | 0.24 (0.22, 0.30) | 0.33 (0.28, 0.38) | 0.0009 | 0.002 | |

| Supramarginal Gyrus | L | 0.29 (0.26, 0.32) | 0.29 (0.26, 0.34) | 0.66 | 0.70 |

| R | 0.25 (0.22, 0.26) | 0.31 (0.27, 0.33) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Lateral Temporal | L | 2.96 (2.78, 3.14) | 2.72 (2.58, 3.04) | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| R | 2.92 (2.74, 3.10) | 3.15 (2.85, 3.46) | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Occipital | L | 1.72 (1.59, 1.90) | 2.02 (1.93, 2.22) | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| R | 1.56 (1.42, 1.69) | 2.03 (1.85, 2.20) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

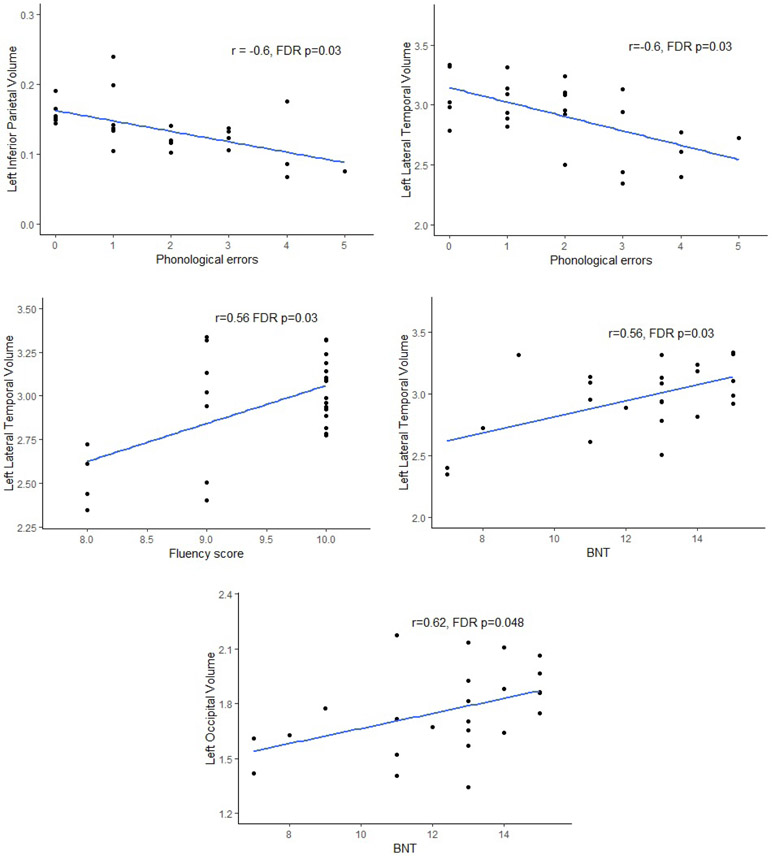

Results of the correlation analyses in PCA participants can be seen in Table 3 and Figure 1. Phonological errors correlated with left inferior parietal (rs=−0.60, p=0.001) and left lateral temporal (rs=−60, p=0.001) volume, such that smaller volume was associated with more phonological errors in PCA. After correction for multiple comparisons, both correlations remained significant (p=0.03, p=0.03, respectively). Additionally, left supramarginal (rs=−0.49, p=0.01) and left occipital (rs=−0.48, p=0.01) volume also correlated with number of phonological errors, but this result did not withstand FDR correction.

Table 3:

Spearman correlations between regional volumes and language measures

| Phonologic errors | Fluency | WAB-repetition | BNT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region of interest | r | p- value |

FDR corrected p-value |

r | p- value |

FDR corrected p-value |

r | p- value |

FDR corrected p-value |

r | p- value |

FDR corrected p-value |

|

| Inferior Parietal | L | −0.60 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.09 | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| R | −0.19 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.97 | |

| Superior Parietal | L | −0.13 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.73 | 0.80 |

| R | −0.07 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.66 | |

| Angular Gyrus | L | −0.24 | 0.22 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.64 | −0.06 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.62 |

| R | −0.11 | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.62 | |

| Supramarginal Gyrus | L | −0.49 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.42 |

| R | −0.28 | 0.16 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.56 | −0.01 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| Lateral Temporal | L | −0.60 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.002 | 0.03 |

| R | −0.39 | 0.046 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.62 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.63 | |

| Occipital | L | −0.48 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.003 | 0.048 |

| R | −0.21 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.62 | |

Figure 1:

Scatter-plots showing the relationship between regional volumes and phonological errors, fluency and Boston Naming Test (BNT).

WAB fluency showed a strong correlation with left lateral temporal lobe volume (rs=0.56, p=0.001), which remained significant after FDR correction (p=0.03). The WAB repetition sub-test correlated with left occipital lobe volume (rs=0.39, p=0.048), but this finding did not remain after FDR correction. The BNT correlated with left occipital (rs=0.56, p=0.003) and left lateral temporal volume (rs=0.62, p=0.002), with both remaining significant after FDR correction (p=0.03, p=0.048, respectively).

Discussion

Although the most prominent clinical symptoms of PCA include visuospatial/perceptual impairments, this study shows that phonological deficits in spoken language production, typically associated with lvPPA, can also be a characteristic of this disorder, occurring in approximately 50% of patients. The severity of phonological errors was associated with volume loss in the left inferior parietal and lateral temporal lobe in PCA; the lateral temporal lobe was also associated with poorer performance on other language tasks.

Language production of the PCA patients revealed phonological errors in the BNT and WAB repetition tasks, which are both tasks that highlight phonological deficits in individuals with lvPPA[15, 20]. One error observed in the speech of PCA participants was sound deletion in the form of cluster simplification. When there are two adjacent consonants within a syllable, they form an onset cluster (e.g., “brick”), but when only one of these consonants is produced, the cluster is simplified. Several PCA patients produced the words “freshly” as “feshly” and “globe” as “gobe”, omitting the second consonant in the cluster, thus simplifying the onset clusters to singleton onsets. Another type of linguistic simplification that was observed was sound substitution. Specifically, sounds that were replaced tended to be replaced by coronal sounds, which are sounds in which the tongue is in contact with the alveolar ridge (e.g., /t, d, s, z/); this is called “coronalization” and is a form of linguistic simplification because coronal sounds are believed to be the least complex sounds[37, 38]. Examples from the present data include utterances like saying “hart” instead of “harp”, “estalator” in place of “escalator”, and “the pastry took” rather than “the pastry cook”, where /t/ replaces /p/ in the word “harp” and /k/ in the words “cook” and “escalator”, respectively.

The PCA participants’ language samples from the BNT and WAB-repetition tasks also included phonological errors of metathesis and consonant harmony. Metathesis is a process in which two sounds are transposed or replace each other within a word, such as saying “tressil” instead of “trellis” or “tedergent” instead of “detergent”. Consonant harmony, on the other hand, is a process of phonological assimilation whereby one consonant adopts the place features (i.e., the place of articulation of the consonant) of another consonant within the syllable or word. One such example was the production of the word “telephone” as “Telephone”: the initial /t/ adopted the labial place feature of the following /f/ (orthographically “ph”).

The types of phonological errors produced by PCA participants were the same as those produced by lvPPA participants. Although not all of these are examples of phonological simplification, they all exhibit phonological patterns that are also observed in child language acquisition data[39-44]. It is generally assumed that as children develop their phonological grammars, they acquire phonological complexity gradually[45], and as this knowledge of phonological complexity increases, the occurrence of these phonological errors decreases. Phonological errors in the speech of individuals affected by neurodegeneration may reflect a decrease in phonological performance that fades in the inverse order that children learning language acquire the same knowledge.

The data presented in this study support claims made by other authors that phonological errors in language production are associated with decreased cortical volume in left temporal and inferior parietal regions[11, 33, 20]. This was evidenced by the significant correlations between severity of phonological errors and these regions in PCA. The left temporoparietal regions are not typically the most affected regions in PCA, but they become affected during the disease and in our cohort were affected to a similar degree as in lvPPA. While we did not find that the frequency of phonological errors differed statistically between PCA and lvPPA, they were somewhat more common in lvPPA, occurring in 70% of patients, and the lvPPA patients produced more errors compared to the PCA patients. The lvPPA patients also performed worse on sentence repetition, naming and fluency tasks. This could suggest that more than just the degree of volume loss of the left temporoparietal cortex contributes to phonological errors and language dysfunction in lvPPA. Reduced connectivity within and between specific brain networks, such as the language and working memory networks, may be an important factor[46 , 17].

We also observed significant correlations between language measures including WAB fluency and BNT and the left lateral temporal lobe in PCA. Previous studies have similarly associated naming with degeneration of the left temporal lobe[47-49]. Interestingly, however, BNT scores also correlated with left occipital volume in PCA. Although the BNT is a test used to measure language and object naming abilities, it relies heavily on visual processing to be able to identify the objects shown in the pictures. Thus, decreased performance on this task in PCA participants may be a result of visual processing abnormalities more so than linguistic abnormalities. Nonetheless, the PCA participants still show evidence of phonological errors like lvPPA in other language production tasks whose results are not complicated by the need for visual processing. Performance on the fluency subtest of the WAB also correlated with volume of the left lateral temporal lobe in PCA, possibly reflecting subtle dysfluency in speech due to word finding pauses, as there were no signs of agrammatism.

Strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size and the fact that the PCA and lvPPA groups were age and disease duration-matched. A limitation is that the speech samples for the PCA cohort were limited to speech produced during the BNT and WAB-repetition sub-test. Uniform samples of spontaneous language production, such as that produced in the WAB picture description task, were not available across cohorts. Nonetheless, the BNT and WAB-repetition tests have been shown to be tests in which phonological errors are present[15, 20], allowing us to directly compare performance and the frequency of phonological errors on these tasks between groups.

In summary, we show that phonological errors are common in PCA. Although the language deficits of PCA are notably less than those of lvPPA, the presence of phonological errors in repetition and naming tasks is not exclusively a characteristic of lvPPA but can also be present in PCA when the cortical structures associated with phonological processing are affected, namely the left temporoparietal regions. These findings add to the clinical characterization of PCA and demonstrate clinical overlap between these two atypical AD syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-AG50603, R01-DC010367 and the Alzheimer’s Association grant NIRG-12-242215.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB # 12-007139, 15-008682 and 09-008772) and all patients provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Benson DF, Davis RJ, Snyder BD. Posterior cortical atrophy. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45(7):789–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang-Wai DF, Graff-Radford N, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Crook R, et al. Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2004;63(7):1168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMonagle P, Deering F, Berliner Y, Kertesz A. The cognitive profile of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2006;66(3):331–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crutch SJ, Lehmann M, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Posterior cortical atrophy. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11(2):170–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed S, Culley S, Blanco-Duque C, Hodges JR, Butler C, Mioshi E. Pronounced Impairment of Activities of Daily Living in Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2020;49(1):48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendez MF, Ghajarania M, Perryman KM. Posterior cortical atrophy: clinical characteristics and differences compared to Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14(1):33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr, Kantarci K, Weigand SD, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, et al. Imaging correlates of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurobiology of aging. 2007;28(7):1051–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh TD, Josephs KA, Machulda MM, Drubach DA, Apostolova LG, Lowe VJ, et al. Clinical, FDG and amyloid PET imaging in posterior cortical atrophy. Journal of neurology. 2015;262(6):1483–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tetzloff KA, Graff-Radford J, Martin PR, Tosakulwong N, Machulda MM, Duffy JR, et al. Regional distribution, asymmetry, and clinical correlates of tau uptake on [18F] AV-1451 PET in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2018;62(4):1713–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Annals of Neurology. 2004;55(3):335–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madhavan A, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, et al. FDG PET and MRI in logopenic primary progressive aphasia versus dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e62471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matias-Guiu JA, Cabrera-Martin MN, Garcia-Ramos R, Moreno-Ramos T, Valles-Salgado M, Carreras JL, et al. Evaluation of the new consensus criteria for the diagnosis of primary progressive aphasia using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38(3-4):147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botha H, Duffy JR, Whitwell JL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Schwarz CG, et al. Classification and clinicoradiologic features of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and apraxia of speech. Cortex. 2015;69:220–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorno-Tempini ML, Brambati SM, Ginex V, Ogar J, Dronkers NF, Marcone A, et al. The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2008;71(16):1227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry ML, Gorno-Tempini ML. The logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2010;23(6):633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitwell JL, Jones DT, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Przybelski SA, et al. Working memory and language network dysfunctions in logopenic aphasia: a task-free fMRI comparison with Alzheimer's dementia. Neurobiology of aging. 2015;36(3):1245–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croot K, Ballard K, Leyton CE, Hodges JR. Apraxia of speech and phonological errors in the diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic and logopenic variants of primary progressive aphasia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leyton CE, Hodges JR. Towards a clearer definition of logopenic progressive aphasia. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2013;13(11):396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petroi D, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Josephs KA. Phonologic errors in the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2014;28(10):1223–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson SM, Henry ML, Besbris M, Ogar JM, Dronkers NF, Jarrold W, et al. Connected speech production in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2010;133(7):2069–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petroi D, Duffy JR, Borgert A, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of phonologic errors in logopenic progressive aphasia. Brain and Language. 2020;204:104773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman L, Selchen D, Black S, Kaplan R, Garnett E, Nahmias C. Posterior cortical dementia with alexia: neurobehavioural, MRI, and PET findings. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1991;54(5):443–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crutch SJ, Lehmann M, Warren JD, Rohrer JD. The language profile of posterior cortical atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(4):460–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnin E, Sylvestre G, Lenoir F, Dariel E, Bonnet L, Chopard G, et al. Logopenic syndrome in posterior cortical atrophy. Journal of neurology. 2013;260(2):528–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavisic IM, Yong KXX, Primativo S, Crutch SJ, Suarez Gonzalez A. Unusual Pattern of Reading Errors in a Patient with Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Case Rep Neurol. 2019May-Aug;11(2):157–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wicklund MR, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, Machulda MM, Josephs KA. Aphasia with left occipitotemporal hypometabolism: A novel presentation of posterior cortical atrophy? Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2013;20(9):1237–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Murray M, Snowden JS, van der Flier WM, et al. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Dement. 2017Aug;13(8):870–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kertesz A Western aphasia battery: Revised. Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lansing AE, Ivnik RJ, Cullum CM, Randolph C. An empirically derived short form of the Boston naming test. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1999;14(6):481–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017March;13(3):205–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mesulam M, Wieneke C, Rogalski E, Cobia D, Thompson C, Weintraub S. Quantitative template for subtyping primary progressive aphasia. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66(12):1545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison T, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, Mesulam M-M. Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2011;76(21):1804–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladefoged P The revised international phonetic alphabet. Language. 1990;66(3):550–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allaire J RStudio: integrated development environment for R. Boston, MA. 2012;770. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stemberger JP, Stoel-Gammon C. The underspecification of coronals: Evidence from language acquisition and performance errors. The special status of coronals: Internal and external evidence. Elsevier; 1991. p. 181–99. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice K Markedness in phonology. The Cambridge handbook of phonology. 2007:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vihman MM. Consonant harmony: Its scope and function in child language. Universals of human language. 1978;2:281–334. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohala DK. Cluster reduction and constraints in acquisition. PhD Dissertation, University of Arizona. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goad H Consonant harmony in child language: an optimality theoretic account. Language Acquisition and Language Disorders. 1997;16:113–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pater J, Werle A. Direction of assimilation in child consonant harmony. The Canadian Journal of Linguistics/La revue canadienne de linguistique. 2003;48(2):385–408. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose S, Walker R. A typology of consonant agreement as correspondence. Language. 2004:475–531. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerlach SR. The acquisition of consonant feature sequences: Harmony, metathesis and deletion patterns in phonological development. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakobson R Child Language, Aphasia and Phonological Universals. Trans R Keiler The Hague: Mouton. 1941/1968. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehmann M, Madison C, Ghosh PM, Miller ZA, Greicius MD, Kramer JH, et al. Loss of functional connectivity is greater outside the default mode network in nonfamilial early-onset Alzheimer's disease variants. Neurobiology of aging. 2015;36(10):2678–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMillan C, Gee J, Moore P, Dennis K, DeVita C, Grossman M. Confrontation naming and morphometric analyses of structural MRI in frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):320–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Domoto-Reilly K, Sapolsky D, Brickhouse M, Dickerson BC, Initiative AsDN. Naming impairment in Alzheimer's disease is associated with left anterior temporal lobe atrophy. Neuroimage. 2012;63(1):348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snowden JS, Harris JM, Thompson JC, Kobylecki C, Jones M, Richardson AM, et al. Semantic dementia and the left and right temporal lobes. Cortex. 2018;107:188–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]