Abstract

There is increasing evidence that the life-course origins of health and development begin before conception. We examined associations between timing and frequency of preconception cannabis and tobacco use and next generation preterm birth (PTB), low birth weight (LBW) and small for gestational age. 665 participants in a general population cohort were repeatedly assessed on tobacco and cannabis use between ages 14–29 years, before pregnancy. Associations were estimated using logistic regression. Preconception parent (either maternal or paternal) daily cannabis use age 15–17 was associated with sixfold increases in the odds of offspring PTB (aOR 6.65, 95% CI 1.92, 23.09), and offspring LBW (aOR 5.84, 95% CI 1.70–20.08), after adjusting for baseline sociodemographic factors, parent sex, offspring sex, family socioeconomic status, parent mental health at baseline, and concurrent tobacco use. There was little evidence of associations with preconception parental cannabis use at other ages or preconception parental tobacco use. Findings support the hypothesis that the early life origins of growth begin before conception and provide a compelling rationale for prevention of frequent use during adolescence. This is pertinent given liberalisation of cannabis policy.

Subject terms: Psychology, Risk factors

Introduction

Birth status profoundly affects health across the life-course1. Prematurity is not only a leading cause of neonatal death but those who survive have greater risks for neurodevelopmental disabilities in later childhood, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in later life, and face greater socio-economic disadvantage2–5. Low birth weight is commonly associated with prematurity and similarly predicts later life cardiometabolic risks6,7 and neurodevelopmental disorders8. Despite improvements in antenatal care, rates of low birthweight and preterm birth remain high in all countries, affecting over one-in-ten births across the globe9,10.

The causes of poor birth outcomes remain unknown in the great majority of cases, though a number of socio-demographic, behavioural and medical risk factors have been identified11. Some of the most clearly documented risks are around maternal substance use.

Maternal antenatal tobacco use predicts both prematurity and low birthweight, and for that reason has become a prevention target in pregnancy12,13. Frequency of substance use is increasingly recognised as an important factor in determining harms14,15, and small-sample studies of maternal tobacco use have indicated a dose–response relationship between frequency or amount of tobacco used during pregnancy, and reduced birth weight16,17. Antenatal cannabis use has been less studied but is linked to poor birth outcomes18–20, although recent research on cannabis use during pregnancy has been critiqued for failing to consider frequency or timing of use21. Given that use in pregnancy is increasingly common22–24, with shifts in legalisation potentially increasing its availability, maternal cannabis use is also now attracting policy attention25–28.

Few studies of antenatal substance use have considered use prior to pregnancy, despite a growing number of reasons to do so. Both tobacco and cannabis use most commonly begin in adolescence, with rates seen to peak in young adulthood prior to median ages of first parenthood29,30. In almost all instances, antenatal tobacco and cannabis use are thus a continuation of use from before pregnancy. Women commonly reduce use of substances on recognition of the pregnancy; an event that typically occurs at 6–8 weeks of gestation, well after the major programming events in early pregnancy. Thus, preconception use may affect birth outcomes even when maternal use ceases with recognition of pregnancy. Equally significant is research outlining mechanisms of intergenerational inheritance through the effects of substance use on parental gametes prior to pregnancy5, which is not limited to effects from maternal use. Findings from animal studies suggest that tobacco and cannabis have the potential to alter patterns of methylation in paternal gametes conferring risks for offspring health and development31–35. Such findings raise a further possibility that exposure of parental gametes to substances such as tobacco and cannabis at times of sensitivity might affect epigenetic marks and subsequent offspring development, even if maternal use ceases before pregnancy36,37.

The present analysis uses data from the 2000 Stories Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study (VAHCS) and Victorian Intergenerational Health Cohort Study (VIHCS) to prospectively examine associations between preconception parent (mothers and fathers) tobacco and cannabis use, and offspring birth outcomes of gestational age, birth weight, and being born small for gestational age.

Aims

Examine the extent to which preconception smoking and cannabis exposure might predict offspring birth outcomes.

Explore whether effects differ by frequency of use or timing.

Explore whether associations observed are robust to adjustment for other adolescent risk factors.

Methods

Design and participants

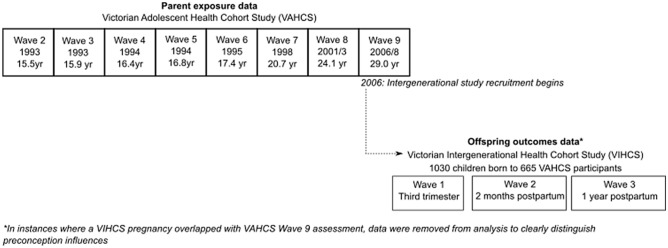

Pre-pregnancy exposure data derive from the VAHCS, a ten-wave cohort study of health in young people living in the state of Victoria, Australia, that commenced in August 1992 (methods outlined in detail in previous publications38). Participants’ parents or guardians provided informed written consent at VAHCS recruitment. At baseline, a representative sample of the Victorian population of adolescents in year 9 at school was recruited and subsequently reviewed at a further five 6-month intervals during adolescence (waves 2–6, mean ages 15.4–17.4 years). From a total intended sample of 2032 students, 1943 (95.6%) participated at least once during the first six (adolescent) waves. Participants were then assessed three times in early adulthood at waves 7, 8, and 9 (respective mean ages 20.7 years, 24.1 years, and 29.1 years).

VIHCS is a longitudinal, prospective cohort study of preconception predictors of early child health and development (methodology and sample characteristics of parents reported previously39). It is the intergenerational arm of the established VAHCS cohort. Study members still active in the VAHCS between 2006 (wave 9) (N = 1671) were screened at six-monthly intervals for pregnancies via SMS, email, and phone calls. Participants reporting a pregnancy or recently born infant were invited to complete telephone interviews in trimester three (VIHCS wave 1), 2 months’ postpartum (VIHCS wave 2) and 1 year postpartum (VIHCS wave 3) for every child born during screening. Participants reporting more than one child born during screening were invited to participate with all eligible children. A total of 665 male and female VAHCS study members participated in VIHCS with 1030 offspring; male VAHCS study members reported on the pregnancy of their partners. See Fig. 1, and Supplementary Figure 1 for sample flow chart.

Figure 1.

Study design for parent exposure and offspring outcomes.

Ethics and role of funders

Data collection protocols for both studies were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia (approval number 26032). The study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. None of the funders had any role in the study design, collection, management or interpretation of data.

Measures

Frequency of parent tobacco use

Use of tobacco at waves 2–9 of the VAHCS was measured by participant self-report of being a non-smoker/ex-smoker, an occasional smoker (not in past week), a light smoker (< 6 days a week), a medium smoker (6/7 days a week, but ≤ 10 cigarettes a day) or a heavy smoker (6/7 days a week, but > 10 cigarettes a day). Exposures were re-categorised to no use/ex-smoker (reference category), occasional/light tobacco use, and daily tobacco use (combining medium and heavy daily use). Separate summary measures of tobacco use frequency were derived for ages 15–17 years (waves 2–6), 20–24 years (waves 7–8), and age 29 years (wave 9; closest to conception), based on the highest reported level of tobacco use during the relevant time period.

Frequency of parent cannabis use

Use of cannabis at VAHCS waves 2–9 was measured through participant self-report of never using cannabis, no use within the previous 6 months, use a few times a year, monthly use, weekly use, or daily use, which was then collapsed to no use within previous 6 months (including never using cannabis), occasional/weekly use (encompassing a few times, monthly and weekly use), and daily use. It should also be noted that after age 17, the period of time covered by this variable was extended to 1 year. Separate summary variables for cannabis use frequency were derived for ages 15–17 years (waves 2–6), 20–24 years (waves 7–8), and 29 years (wave 9; closest to conception), based on the highest reported level of cannabis use during the relevant time period.

Outcome measures

Offspring gestational age at birth (completed weeks) and birth weight (kg) were self-reported by parent participants. To derive binary outcomes, offspring were classified as preterm births (PTB) if they were born at less than 37 completed weeks of gestation, and were classified as low birth weight (LBW) if weighing < 2500 g when born. Birthweight Z-scores were calculated relative to the British Growth Reference40; offspring were categorised as small for gestational age (SGA) if birthweight was less than the 10th percentile for gestational age (Z-score < − 1.28 SD).

Covariates

Offspring sex was determined through parental self report after birth. For all other covariates, parents of the offspring reported these data during their participation in VAHCS. Parent sex was determined through self-report. Family socio-economic status (SES) was calculated by home postcode at study entry using the Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD) from the Australian Bureau of Statistics Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA), then dichotomized so that scores up to the 20th percentile indicated that participants were relatively disadvantaged. Between ages 15–24, VAHCS participants were asked to report on their parents (offspring grandparents) education level, with response options categorised as high school not completed/high school completed/university degree, and their parents (offspring grandparents) smoking status, with response options dichotomised to never or occasionally/most days or every day. For both variables the highest reported level for either parent at any time point was used to determine the status of these summary variables.

Parent mental health at baseline was assessed during VAHCS participation using the revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R)41 at age 15–17. The CIS-R is a branched psychiatric interview designed to assess symptoms of depression and anxiety in non-clinical populations. The total scores on the CIS-R were dichotomized so that scores ≥ 12 indicated a mixed depression-anxiety state at a lower threshold than syndromes of major depression and anxiety disorder, but where clinical intervention would be appropriate41.

Analysis

Data were analysed in Stata 15. We report the crude prevalence of each birth outcome (PTB, LBW and SGA) by frequency of preconception substance use and antenatal tobacco/cannabis exposure (confidence intervals provided as data are imputed). Logistic regression analyses were conducted for each birth outcome measure, to examine the relationship with each exposure (parental cannabis or tobacco use) at 15–17 years, 20–24 years, and 29 years. Robust (Huber–White) standard errors were used in all analyses to account for clustering by family as more than one offspring within the sample could be born from the same parent.

Multivariable models are adjusted for offspring sex, parent sex, family SES, grandparent education level, grandparent smoking status, parent mental health at age 15–17, frequency of parent use of the substance at previous ages (where appropriate), and concurrent use of cannabis for models where tobacco is the exposure and vice versa. In supplementary sensitivity analyses, we repeated all regression analyses (a) with continuous outcome measures using linear regression and (b) further adjusted for periconceptional/antenatal cannabis/tobacco use.

Multiple imputation

Most offspring had available data on at least one wave of parent preconception substance use. Missing data in all analysis variables (exposures measured at each of waves 2–9, outcomes, covariates) were addressed through multiple imputation using fully conditional specification—moving time window (FCS-MTW) method42: a series of univariate regression models which impute each incomplete variable sequentially given all other variables. Each conditional model included all other outcomes and covariates, as well as exposures measured at the same and adjacent waves as predictors. Maternal weight before pregnancy, maternal high blood pressure/pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, primiparae and multiple births (both associated with incomplete offspring birth outcome variables), and highest level of parent education (associated with being missing data on the exposure and outcome variables) were included as auxiliary variables. Summary variables for parent frequency of tobacco and cannabis use were derived following multiple imputation. Estimates were obtained by pooling results across 65 imputed datasets using Rubin’s rules.

Population attributable fraction (PAF)

See Appendix 1 for methodology for calculation of the population attributable fraction.

Results

Sample description

Table 1 summarises the estimated frequency of offspring outcomes, preconception exposures, antenatal tobacco/cannabis use and potential confounders in the imputed data. See Supplementary Table 1 for proportion of missing data of study variables in the observed data. Overall, 21% of offspring had occasional parental tobacco exposure at ages 15–17, 11% at ages 20–24, and 6% at age 29; proportions of offspring who had daily parental tobacco exposure at ages 15–17, 20–24 and 29 were 20%, 32% and 17% respectively. For cannabis, 30% of offspring had occasional parental cannabis exposure at age 15–17, 54% at age 20–24, and 16% at age 29; proportions of offspring who had daily parental cannabis exposure at ages 15–17, 20–24 and 29 were 3%, 6% and 5% respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1030 children born to 665 parents in the Victorian Intergenerational Health Cohort Study (data imputed and N estimated from proportions).

| Study variable | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Outcomes | ||

| Preterm birth | 70 | 6.8 |

| Low birth weight | 55 | 5.4 |

| Small for gestational age | 63 | 6.1 |

| Preconception exposures | ||

| Parent tobacco use: 15–17 years | ||

| None | 601 | 58.3 |

| Occasional/weekly | 219 | 21.3 |

| Daily | 210 | 20.4 |

| Parent tobacco use: 20–24 years | ||

| None | 587 | 57.0 |

| Occasional/weekly | 118 | 11.5 |

| Daily | 324 | 31.5 |

| Parent tobacco use: 29 years | ||

| None | 791 | 76.8 |

| Occasional/weekly | 64 | 6.2 |

| Daily | 175 | 16.9 |

| Parent cannabis use: 15–17 years | ||

| None | 695 | 67.5 |

| Occasional/weekly | 309 | 30.0 |

| Daily | 26 | 2.6 |

| Parent cannabis use: 20–24 years | ||

| None | 404 | 39.3 |

| Occasional/weekly | 559 | 54.3 |

| Daily | 66 | 6.4 |

| Parent cannabis use: 29 years | ||

| None | 822 | 79.8 |

| Occasional/weekly | 159 | 15.5 |

| Daily | 49 | 4.7 |

| Covariates | ||

| Parent sex: females | 609 | 59.1 |

| Offspring sex: females | 519 | 50.4 |

| Grandparent highest level of education | ||

| Did not complete high school | 340 | 33.0 |

| Completed high school | 339 | 32.9 |

| Completed university | 351 | 34.1 |

| Grandparental divorce | 180 | 17.6 |

| Grandparental daily tobacco use | 369 | 35.8 |

| Parental adolescent mental health problemsa | 396 | 38.4 |

| Low family SESb | 211 | 20.5 |

aDepression/anxiety assessed prospectively through the revised Clinical Interview Schedule.

bHome postcode at study entry within the lowest 20% of the Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage.

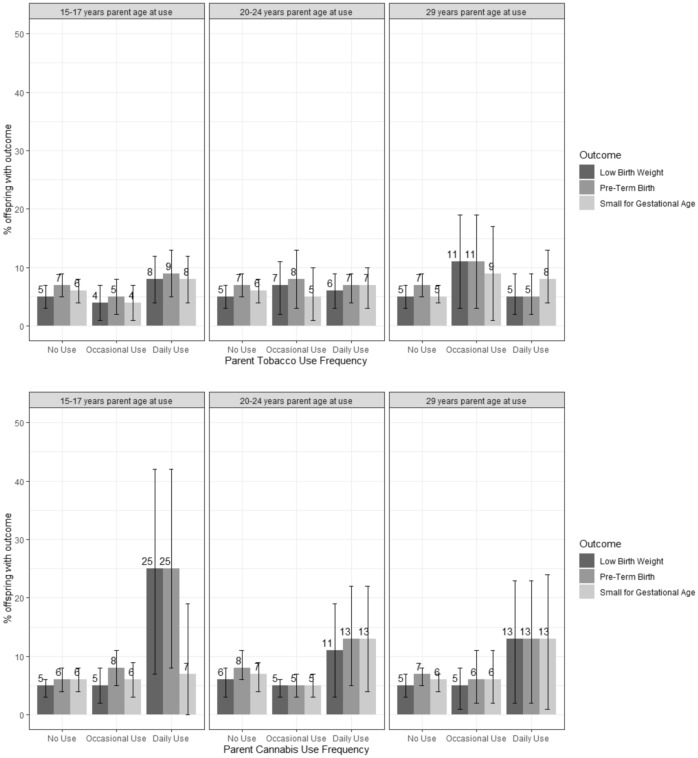

Figure 2 shows the estimated proportions of all birth outcomes in the imputed data, by timing and frequency of parental substance use. Of the offspring whose parents reported daily cannabis use at age 15–17, 25–26% were born either PTB or LBW. In contrast, PTB or LBW were observed in only 11–13% of offspring whose parents reported daily cannabis use at either age 20–24 or age 29.

Figure 2.

Estimate proportion of children with each birth outcome by frequency of parent substance use in 1030 children born to 665 parents In the VIHCS study (imputed data).

Preconception parent substance use and preterm birth (PTB)

There was strong evidence that daily cannabis use at age 15–17 was associated with over a six-fold increase in the odds of offspring PTB, after adjusting for offspring sex and baseline sociodemographic factors, parent sex, family SES, parent mental health at baseline and concurrent tobacco use (aOR 6.65, 95% CI 1.92, 23.09) (Table 2, Fig. 2). Similar associations were observed for the continuous outcome of gestational age in linear models with offspring whose parents reported daily cannabis use at age 15–17 being born on average more than 1 week earlier than those whose parents reported no cannabis use (mean difference − 1.49 weeks, 95% CI − 3.00, 0.03; Supplementary Table 2). There was no evidence that these associations attenuated after further adjustment for any periconceptional/antenatal use (Supplementary Appendix 2, Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of relationship between tobacco/cannabis use frequency at age 15–17, 20–24 and 29, and preterm birth in 1030 children born to 665 parents (OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval).

| Preconception substance use | Offspring preterm birth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||||

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Parent age 15–17 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.73 | (0.31–1.72) | 0.47 | 0.53 | (0.22–1.33) | 0.18 |

| Daily | 1.32 | (0.66–2.64) | 0.43 | 0.71 | (0.32–1.60) | 0.41 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.42 | (0.74–2.70) | 0.29 | 1.65 | (0.80–3.41) | 0.18 |

| Daily | 5.52 | (1.76–17.32) | 0.00 | 6.65 | (1.92–23.09) | 0.00 |

| Parent age 20–24 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.14 | (0.43–3.01) | 0.80 | 1.34 | (0.50–3.60) | 0.56 |

| Daily | 0.97 | (0.51–1.82) | 0.92 | 0.79 | (0.33–1.88) | 0.59 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.57 | (0.31–1.07) | 0.08 | 0.37 | (0.18–0.76) | 0.01 |

| Daily | 1.64 | (0.69–3.91) | 0.26 | 0.58 | (0.16–2.08) | 0.41 |

| Parent age 29 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.65 | (0.64–4.25) | 0.30 | 1.84 | (0.70–4.79) | 0.21 |

| Daily | 0.77 | (0.32–1.86) | 0.57 | 0.62 | (0.23–1.70) | 0.35 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.96 | (0.45–2.05) | 0.92 | 0.71 | (0.26–1.93) | 0.51 |

| Daily | 2.02 | (0.67–6.06) | 0.21 | 1.47 | (0.39–5.53) | 0.57 |

aAll adjusted models adjusted for baseline/adolescent covariates: parent sex, offspring sex, family SES, grandparent education level, grandparent smoking status, adolescent mental health, and concurrent use of cannabis for models where tobacco is the exposure and vice versa. Adjusted models at age 20–24 years also include adjustment for frequency of use of the substance at age 15–17 years. Adjusted models at age 29 years models also include adjustment for frequency of use of the substance at age 15–17 and age 20–24 years.

Preconception parent substance use and low birth weight (LBW)

As with preterm birth, there was strong evidence that daily cannabis use at age 15–17 was associated with an almost sixfold increase in odds of offspring being born LBW (aOR 5.84, 95% CI 1.70–20.08) (Table 3). Similarly, in the linear analysis of continuous outcomes, parent’s daily cannabis use in adolescence was associated with an average reduction in birth weight by 400 g after adjustment for all confounders stated above (mean difference − 0.40 kg, 95% CI − 0.85, 0.06; Supplementary Table 3). There was no evidence that these associations attenuated after further adjustment for any periconceptional/antenatal use (Supplementary Appendix 2, Table 2).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of relationship between tobacco/cannabis use frequency at age 15–17, 20–24 and 29, and low birthweight in 1030 children born to 665 parents (OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval).

| Preconception substance use | Offspring low birthweight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||||

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Parent age 15–17 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.86 | (0.34–2.20) | 0.75 | 0.78 | (0.29–2.12) | 0.63 |

| Daily | 1.65 | (0.77–3.51) | 0.19 | 1.31 | (0.55–3.12) | 0.55 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.06 | (0.50–2.26) | 0.87 | 1.01 | (0.45–2.28) | 0.98 |

| Daily | 6.60 | (2.09–20.89) | 0.00 | 5.84 | (1.70–20.08) | 0.01 |

| Parent age 20–24 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.43 | (0.48–4.25) | 0.52 | 1.63 | (0.53–4.98) | 0.39 |

| Daily | 1.34 | (0.67–2.68) | 0.41 | 1.12 | (0.41–3.07) | 0.83 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.79 | (0.39–1.61) | 0.52 | 0.56 | (0.23–1.35) | 0.20 |

| Daily | 2.01 | (0.71–5.67) | 0.19 | 0.83 | (0.20–3.50) | 0.80 |

| Parent age 29 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 2.30 | (0.81–6.52) | 0.12 | 2.25 | (0.60–8.39) | 0.23 |

| Daily | 1.12 | (0.46–2.75) | 0.81 | 0.73 | (0.24–2.21) | 0.58 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.92 | (0.38–2.25) | 0.86 | 0.63 | (0.18–2.19) | 0.47 |

| Daily | 2.68 | (0.88–8.19) | 0.08 | 1.66 | (0.40–6.97) | 0.49 |

aAll adjusted models adjusted for baseline/adolescent covariates: parent sex, offspring sex, family SES, grandparent education level, grandparent smoking status, adolescent mental health, and concurrent use of cannabis for models where tobacco is the exposure and vice versa. Adjusted models at age 20–24 years also include adjustment for frequency of use of the substance at age 15–17 years. Adjusted models at age 29 years models also include adjustment for frequency of use of the substance at age 15–17 and age 20–24 years.

There was no evidence of an association with preconception tobacco use or with parent occasional/weekly cannabis use at any preconception phase on binary LBW (see Table 3). In analysis of the continuous birth weight outcome there was weak evidence that parental daily tobacco use at age 20–24 was associated with an increase in offspring birth weight, after adjustment for all confounders (mean difference 0.14 kg, 95% CI 0.01, 0.27; Supplementary Table 3).

Preconception parent substance use and small for gestational age (SGA)

There was little evidence for an association between parental tobacco or cannabis use at any age and offspring being small for gestational age (Table 4), and similar results were observed in the linear regression analysis (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of relationship between tobacco/cannabis use frequency at age 15–17, 20–24 and 29, and small for gestational age in 1030 children born to 665 parents (OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval).

| Preconception substance use | Offspring small for gestational age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||||

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Parent age 15–17 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.66 | (0.28–1.58) | 0.35 | 0.62 | (0.24–1.59) | 0.32 |

| Daily | 1.31 | (0.67–2.54) | 0.43 | 1.39 | (0.59–3.27) | 0.46 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.07 | (0.57–2.02) | 0.84 | 0.99 | (0.45–2.19) | 0.98 |

| Daily | 1.16 | (0.20–6.87) | 0.87 | 0.82 | (0.10–6.52) | 0.85 |

| Parent age 20–24 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.83 | (0.31–2.22) | 0.71 | 0.94 | (0.33–2.68) | 0.90 |

| Daily | 1.09 | (0.58–2.06) | 0.78 | 0.97 | (0.36–2.60) | 0.96 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 0.68 | (0.36–1.28) | 0.23 | 0.64 | (0.30–1.37) | 0.25 |

| Daily | 2.06 | (0.84–5.06) | 0.12 | 1.90 | (0.57–6.25) | 0.29 |

| Parent age 29 years | ||||||

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.80 | (0.66–4.94) | 0.25 | 2.50 | (0.82–7.62) | 0.11 |

| Daily | 1.64 | (0.84–3.21) | 0.15 | 1.94 | (0.81–4.68) | 0.14 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Occasional/weekly | 1.12 | (0.51–2.49) | 0.77 | 0.97 | (0.33–2.81) | 0.95 |

| Daily | 2.33 | (0.79–6.89) | 0.13 | 1.91 | (0.52–7.03) | 0.33 |

aAll adjusted models adjusted for baseline/adolescent covariates: parent sex, offspring sex, family SES, grandparent education level, grandparent smoking status, adolescent mental health, and concurrent use of cannabis for models where tobacco is the exposure and vice versa. Adjusted models at age 20–24 years also include adjustment for frequency of use of the substance at age 15–17 years. Adjusted models at age 29 years models also include adjustment for frequency of use of the substance at age 15–17 and age 20–24 years.

Post-hoc calculation of PAF

The adjusted attributable fraction for the association between daily cannabis use age 15–17 and preterm birth was 20%, and 10% for low birthweight (see Appendix 1 for full details).

Discussion

We found striking associations between higher frequency parental cannabis use in adolescence and later birth outcomes of offspring; daily use was associated with a more than six-fold increase in the odds of premature birth. These associations remained after adjustment for a broad range of confounders. There was a similar association with offspring low birth weight but no effect on being born small for gestational age, suggesting that the association with low birthweight reflects gestational age at birth, rather than adverse effects on fetal growth. In contrast, there was no consistent association between preconception tobacco use and offspring birth outcomes, and no dose–response was observed at lower levels of cannabis frequency. The adjusted attributable fractions for the association with preterm birth was 20%; if replicated in larger samples, this suggests that eliminating daily cannabis use in adolescents could reduce rates of preterm birth.

Rates of prematurity and low birth weight were consistent with estimated rates for these outcomes in Australia in the 2000s9,43. Rates of adolescent cannabis use were similar to those of adolescents in the Australian population in the 1990s44 (the period in which the parents in VAHCs were adolescent).

There is a range of possible explanations for the observed associations. Unmeasured confounding from parental exposure to stress and social disadvantage cannot be excluded, despite controlling for grandparental education and baseline mental health as indicators of stress and disadvantage. Adolescent cannabis use may also increase risk of offspring preterm birth through a number of mediating psychosocial pathways that warrant further investigation in larger samples. For example, there is evidence that heavy or regular cannabis use may influence later health risks such as other substance use45, poor nutrition46, and intimate partner violence47, each in turn associated with heightened risk of offspring preterm birth48–51.

An alternative potential explanation is continuity of use from adolescence to the periconception and antenatal period, with potential effects on spermatogenesis and the gestational environment52. We found that adjustment for any periconceptional or antenatal use did not attenuate findings, but it is plausible that heavier dose or longer duration of periconceptional or antenatal use may mediate preconception associations53. However, our findings were not necessarily consistent with this explanation. Effect sizes for offspring birth outcomes were larger for distal daily cannabis use at ages 15–17 than for the more proximal (to the time of conception, which was at age 29 years or older) daily cannabis use at age 20–24.

An intriguing further possibility is the persistence of the effect of preconception adolescent daily cannabis use on reproductive biology. Animal studies have previously shown links between cannabis use and gonadal function and both male and female fertility54, and dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system has been linked to pregnancy outcomes55. There is some evidence that exposures during prepuberty may be particularly influential on reproductive development in males37. In animal studies parental cannabis use predicts altered gamete epigenetic marks involving both DNA methylation and histone modification, with phenotypic change in the next generation56,57, and recent evidence has indicated cannabinoid exposure affects human sperm methylation34. Such mechanisms could go partway to explaining our results.

This the first prospective study of associations between parent preconception tobacco and cannabis use and birth outcomes. Strengths of the study include the repeated assessment of cannabis and tobacco use across 15 years from adolescence to young adulthood before pregnancy. Alongside these there are certain limitations. Some analyses may be limited by low power; power precluded consideration of differential effects by sex of parent or offspring, which remains an important question for future research. Effect sizes were large, with confidence intervals well above one for binary outcomes and supplementary linear analyses complementing the main findings, but replication of these results in larger intergenerational samples or pooled samples with similarly strong longitudinal designs is now needed. Substance use was assessed by self-report, with potential for reporting bias, though there is evidence that maternal report of tobacco use during pregnancy is valid58, and rates of cannabis use in this sample were consistent with rates amongst adolescents in the general population44. Prospective substance use data were only available for the parent who was recruited to the original VAHCS cohort.

We accounted for a range of potential confounding variables, but potential for unmeasured confounding remains. VAHCS maintained a high retention rate, and 85% of those with live births during screening participated in VIHCS. Moreover, the retained and participating samples were broadly representative of the baseline VAHCS and eligible VIHCS samples on measured baseline characteristics. Nonetheless, as with all cohort studies, potential for selection bias due to differences on unmeasured characteristics remains. Similarly, we accounted for potential biases due to missing data using multiple imputation with a rich covariate and auxiliary variable set. Finally, it is common in Australia for cannabis to be smoked with tobacco59 we cannot rule out an effect of an interaction with the combined use of these drugs.

Frequent adolescent cannabis use was most common in males60, a group largely overlooked in relation to public health messaging regarding substance use and birth outcomes where the focus has been predominantly on antenatal tobacco and alcohol use in women16,17. Our findings require replication in larger and diverse samples, along with investigation of the potential mechanisms of transmission. Whether mediated by direct and enduring effects on parental reproductive biology, continued use into the periconceptional period, or other psychosocial pathways, our findings support expansion of the developmental origins of disease hypothesis to include the time before conception and provide a compelling new rationale for reducing frequent use during adolescence, particularly in an era where cannabis legalisation in many jurisdictions is increasing cannabis availability.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families who have participated in the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study and the Victorian Intergenerational Health Cohort Study for their invaluable contributions, as well as all collaborators and the study teams involved in the data collection and management.

Author contributions

The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. G.P. is responsible for establishing the cohort. L.A.H., E.A.S. and G.P. conceived the present analyses. L.A.H., E.A.S., M.M.-B. and G.P. contributed to the analysis plan. L.A.H. conducted the analyses with assistance from H.M.H., E.A.S., D.B., M.M.-B. and M.M. L.A.H., G.P., E.A.S., M.M.-B., C.A.O., L.W.D. and J.M.C. contributed to the interpretation of the data. LH drafted the first iteration of the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the study to be published and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP180102447). Data collection for VIHCS was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council; Australian Rotary Health; Colonial Foundation; Perpetual Trustees; Financial Markets Foundation for Children (Australia); Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation; and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. GP is supported by an NHMRC Senior Principle Research Fellowship (APP1117873). Research at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Program. This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Wellcome Trust 209158/Z/17/Z (LH). For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interests

LD reports Grants from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, during the conduct of the study. There are no other reported conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-95460-2.

References

- 1.Stein AD, et al. Birth status, child growth, and adult outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. J. Pediatr. 2013;163:1740–1746.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer MS, et al. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. Fetal and Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. JAMA. 2000;284:843–849. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2008;371:261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindström K, Winbladh B, Haglund B, Hjern A. Preterm infants as young adults: A Swedish National Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:70–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen LG, et al. Birth weight, childhood body mass index and risk of coronary heart disease in adults: Combined historical cohort studies. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuart A, Amer-Wahlin I, Persson J, Kallen K. Long-term cardiovascular risk in relation to birth weight and exposure to maternal diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;168:2653–2657. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Losh M, Esserman D, Anckarsater H, Sullivan PF, Lichtenstein P. Lower birth weight indicates higher risk of autistic traits in discordant twin pairs. Psychol. Med. 2012;42:1091–1102. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blencowe H, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2019;7:e849–e860. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30565-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chawanpaiboon S, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2019;7:e37–e46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrero DM, et al. Cross-country individual participant analysis of 4.1 million singleton births in 5 countries with very high human development index confirms known associations but provides no biologic explanation for 2/3 of all preterm births. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Been JV, et al. Effect of smoke-free legislation on perinatal and child health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2014;383:1549–1560. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newnham JP, et al. Strategies to prevent preterm birth. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:584. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran HV, et al. Keep off the grass? Cannabis, cognition and addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016;17:293–306. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction. 2015;110:19–35. doi: 10.1111/add.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vila Candel R, Soriano-Vidal FJ, Hevilla Cucarella E, Castro-Sanchez E, Martin-Moreno JM. Tobacco use in the third trimester of pregnancy and its relationship to birth weight. A prospective study in Spain. Women Birth. 2015;28:E134–E139. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owili PO, Muga MA, Kuo H-W. Gender difference in the association between environmental tobacco smoke and birth weight in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1409. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn JKL, et al. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009986. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leemaqz SY, et al. Maternal marijuana use has independent effects on risk for spontaneous preterm birth but not other common late pregnancy complications. Reprod. Toxicol. Elmsford N. 2016;62:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corsi DJ, et al. Association between self-reported prenatal cannabis use and maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322:145–152. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverstein M, Howell EA, Zuckerman B. Cannabis use in pregnancy: A tale of 2 concerns. JAMA. 2019;322:121–122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal A, et al. Alcohol, cigarette, and cannabis use between 2002 and 2016 in pregnant women from a nationally representative sample. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:95–96. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkow ND, Han B, Compton WM, McCance-Katz EF. Self-reported medical and nonmedical cannabis use among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322:167–169. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young-Wolff KC, et al. Self-reported daily, weekly, and monthly cannabis use among women before and during pregnancy. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2:e196471–e196471. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corsi DJ, Hsu H, Weiss D, Fell DB, Walker M. Trends and correlates of cannabis use in pregnancy: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2017. Can. J. Public Health. 2019;110:76–84. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown QL, et al. Trends in marijuana use among pregnant and non-pregnant reproductive-aged women, 2002–2014. JAMA. 2017;317:207–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozano J, et al. Prevalence of gestational exposure to cannabis in a Mediterranean city by meconium analysis. Acta Paediatr. Oslo Nor. 2007;1992(96):1734–1737. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Marroun H, et al. An epidemiological, developmental and clinical overview of cannabis use during pregnancy. Prev. Med. 2018;116:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brook JS, Zhang C, Leukefeld CG, Brook DW. Marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Developmental trajectories and their outcomes. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016;51:1405–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones HJ, et al. Association of combined patterns of tobacco and cannabis use in adolescence with psychotic experiences. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75:240–246. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibn Lahmar Andaloussi Z, Taghzouti K, Abboussi O. Behavioural and epigenetic effects of paternal exposure to cannabinoids during adolescence on offspring vulnerability to stress. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. Off. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Neurosci. 2019;72:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenkins TG, et al. Cigarette smoking significantly alters sperm DNA methylation patterns. Andrology. 2017;5:1089–1099. doi: 10.1111/andr.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin ED, et al. Paternal THC exposure in rats causes long-lasting neurobehavioral effects in the offspring. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2019;74:106806. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy SK, et al. Cannabinoid exposure and altered DNA methylation in rat and human sperm. Epigenetics. 2018;13:1208–1221. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2018.1554521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrott R, et al. Sperm DNA methylation altered by THC and nicotine: Vulnerability of neurodevelopmental genes with bivalent chromatin. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16022. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72783-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassoler FM, Byrnes EM, Pierce RC. The impact of exposure to addictive drugs on future generations: Physiological and behavioral effects. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu H, Hauser R, Krawetz SA, Pilsner JR. Environmental susceptibility of the sperm epigenome during windows of male germ cell development. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015;2:356–366. doi: 10.1007/s40572-015-0067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton GC, et al. The prognosis of common mental disorders in adolescents: A 14-year prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2014;383:1404–1411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spry E, et al. The Victorian Intergenerational Health Cohort Study (VIHCS): Study design of a preconception cohort from parent adolescence to offspring childhood. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2020;34:88–100. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cole TJ, Williams AF, Wright CM, RCPCH Growth Chart Expert Group Revised birth centiles for weight, length and head circumference in the UK-WHO growth charts. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2011;38:7–11. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2011.544139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: A standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol. Med. 1992;22:465–486. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huque MH, Carlin JB, Simpson JA, Lee KJ. A comparison of multiple imputation methods for missing data in longitudinal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018;18:168. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0615-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blencowe H, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lynksey, M. T. & Hall, W. Cannabis Use Among Australian Youth. Technical Report No. 66 (National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney, 1998).

- 45.Silins E, et al. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: An integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korn L, Haynie DL, Luk JW, Simons-Morton BG. Prospective associations between cannabis use and negative and positive health and social measures among emerging adults. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2018;58:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012;26:236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0024855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frey HA, Klebanoff MA. The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth. Semin. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2016;21:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill A, Pallitto C, McCleary-Sills J, Garcia-Moreno C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and selected birth outcomes. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ. Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2016;133:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vogel JP, et al. The global epidemiology of preterm birth. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018;52:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuppia L, Franzago M, Ballerini P, Gatta V, Antonucci I. Epigenetics and male reproduction: The consequences of paternal lifestyle on fertility, embryo development, and children lifetime health. Clin. Epigenet. 2015;7:120. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stephenson J, et al. Before the beginning: Nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health. Lancet. 2018;391:1830–1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paul, S. & Bogdan, R. Prenatal Cannabis Exposure and Childhood Outcomes: Results from the ABCD Study®. https://doi.org/10.15154/1519186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Szutorisz H, Hurd YL. Epigenetic effects of cannabis exposure. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016;79:586–594. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park B, McPartland JM, Glass M. Cannabis, cannabinoids and reproduction. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2004;70:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perez MF, Lehner B. Intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:143–151. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sen A, et al. Multigenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans: DNA methylation changes associated with maternal exposure to lead can be transmitted to the grandchildren. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14466. doi: 10.1038/srep14466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knopik VS, Marceau K, Palmer RHC, Smith TF, Heath AC. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring birth weight: A genetically-informed approach comparing multiple raters. Behav. Genet. 2016;46:353–364. doi: 10.1007/s10519-015-9750-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hindocha C, Freeman TP, Ferris JA, Lynskey MT, Winstock AR. No smoke without tobacco: A global overview of cannabis and tobacco routes of administration and their association with intention to quit. Addict. Disord. 2016 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patton GC, et al. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: Cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.