Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic has had disproportionate effects on economically and socially marginalized people. We explore the effects on low-wage migrant workers (migrant workers) in three countries: Singapore, South Korea and Brazil, through the lens of the social determinants of health. Our analysis shows that governments missed key opportunities to mitigate pandemic risks for migrant workers. Government measures demonstrate potential for effective and sustainable policy reform, including universal and equitable access to healthcare, social safety nets and labour rights for migrant workers—key concerns of the Global Compact for Migration. A whole-of-society and a whole-of-government approach with Health in All Policies, and migrant worker frameworks developed by the World Health Organization could be instrumental. The current situation indicates a need to frame public health crisis responses and policies in ways that recognize social determinants as fundamental to health.

Keywords: Low-wage migrant workers, Social determinants of health, Health policy, South Korea, Singapore, Brazil

Introduction

Migrant workers comprise a group that is highly vulnerable to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease it causes, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and its socio-economic effects. We examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on low-wage migrant workers (hereafter ‘migrant workers’) through the lens of social determinants of health (SDoH) based on three case studies from Singapore, South Korea and Brazil. We define migrant workers as those who move away from their places of usual residence, within a country (internal) or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, for the purpose of employment [1]. Low-wage workers are commonly defined as workers earning less than two-thirds of the median wage of equivalent full-time local workers [2].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on the SDoH, health inequities arise as a result of the “circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age and the systems put in place to deal with illness” [3]. The SDoH lie at the root of the inequities in health and are relevant to both communicable and noncommunicable diseases. These factors are shaped by political determinants—the global, national and local distribution of money, power and resources—requiring engagement of sectors other than health to improve health and reduce vulnerabilities [4].

A succession of international and regional agreements and mechanisms by the United Nations (UN) and other international organizations have been instrumental in framing migrant workers’ issues [5, 6]. The 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), a non-binding agreement endorsed by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, calls for a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach to all dimensions of migration including the migration cycle and migrant workers. The migration cycle can be defined as the process of migration from a country of origin to a destination and vice versa. The cycle includes pre-departure, departure, short-/long-term transit, temporary or permanent resettlement, return to the country of origin and remigration (departure) [7].

The GCM is also consistent with the Health in All Policies approach developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and employed in their migrant worker framework [8]. These documents provide a pathway for healthcare workers and others to engage with migration issues.

Research by Castaneda and colleagues in the last decade established the importance of migration as a SDoH [9]. They argue that migration is both a consequence of the social determinants and itself a SDoH that creates profound challenges for individuals and communities, with ongoing social, economic and health ramifications. These authors maintain that relationships between migration and SDoH are multi-causal and complex, and that more attention needs to be paid to the structural determinants. The 2018 UCL-Lancet Special Commission on Migration and Health study emphasized the lack of safety nets, safety at work, rights and social support for migrant workers, and the effects of these on their health, as well as the links between migrant workers and globalization, supply and demand [7]. These findings highlight the implications of ‘upstream’ social and political determinants on migrant workers’ health. ‘Upstream determinants’ can be described as overarching factors that are largely beyond the control of the individual and have significant influence over more proximal or ‘downstream’ determinants of health [10]. Upstream determinants have been referred to as social disadvantage, risk exposure and social inequities that play a fundamental causal role in poor health outcomes [11, 12]. Thus, they represent important opportunities for improving health and reducing health disparities [12]. The experiences of low-wage migrant workers have been neglected in previous studies [13], a major oversight considering the increased health and other risks.

We conducted a literature review to examine the question: In what ways can the social determinants of health be used to assess effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and wellbeing of low-wage migrant workers? We chose Singapore and South Korea as they are destination countries for migrant workers; we chose Brazil as both a destination and dispatch country. The choice of these cases was both purposeful and a convenience sample—for each country, there are differences in the roles of migrant workers, legal and health structures and responses to the pandemic. These countries also took different approaches to the implementation (or not) of the GCM.

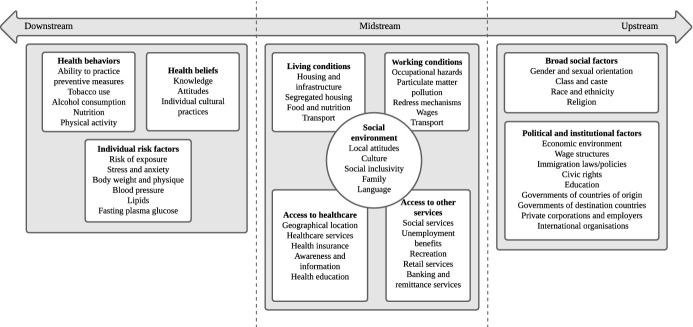

We undertook a document analysis to gather information on demographics, healthcare, government policies, civil society context and working and living conditions from the three countries for use in the analysis. Sources included peer-reviewed academic journals, government documents and news articles up to the first week of September 2020. We examined data to identify relationships between broad structural determinants and migrant worker health. We used a root cause analysis with logic trees to explore some of the key relationships between the SDoH and effects of COVID-19 [14]. Based on this analysis, we offer recommendations on current global frameworks and organizations to provide long-term solutions for addressing the broader health, economic and human rights issues exposed by the pandemic. We base Fig. 1 on findings from the background literature and discussions with experts in the field. It provides a visual model for exploring the situation of migrant workers that we applied in our analysis. We did not include all aspects in Fig. 1 in our analysis here, yet we suggest it for possible use in future research.

Fig. 1.

The model of social determinants of health related to the health and wellbeing of migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic

Singapore: from the dormitories of migrant workers

Towards the end of March 2020, Singapore appeared to have maintained a successful record in keeping the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections low (cases per one million population) compared to the other countries [15]. The media presented the spike in cases in Singapore as a ‘second wave’, implying that relaxation of preventive measures may have precipitated the new crisis, but is more accurately understood as a continuation of the initial outbreak. Reports of the first few COVID-19 cases among migrant workers in Singapore appeared in early February, followed by a sharp increase in incidence from early April [15]. Well over 90% of all laboratory-confirmed infections from April to early September 2020 occurred among migrant workers living in dormitories.

In 2019, the total foreign workforce in Singapore consisted of 1,427,500 migrants (25% of the total population), and of these, 293,300 (20.55%) worked in construction. Migrant workers are generally hired to do the so-called ‘3D-work’—dirty, dangerous and demeaning—that is traditionally shunned by Singaporeans. These industries include construction, process (including production processes in plants in the manufacturing of petroleum, petrochemicals, specialty chemicals and pharmaceutical products) and marine shipyards. Most migrant workers are male and come from Bangladesh, India and Myanmar. Their demographic data are not available from government agencies, and few studies exist on migrant-related health or policies.

Increased incidence of COVID-19 in migrant worker communities may have resulted from economic and social disparities in Singapore’s socio-political landscape [15]. This increase was likely to have been precipitated by policy gaps related to the outbreak at its onset, at least in part. For example, a Ministry of Manpower advisory on 19 February 2020 warned employers that their work pass privileges—required for employers to employ foreign workers—would be suspended if they continued to send migrant workers to public hospitals for testing (for SARS-CoV-2). This practice had overburdened medical facilities at tertiary hospitals. Despite this advisory, reasonably accessible testing facilities and services for migrant workers, along with translated inpatient and outpatient screening questionnaires, did not become available until the first and the second weeks of April 2020, respectively.

Researchers have identified language and cultural barriers, financial insecurities (particularly from debts incurred through the recruitment process) and fear of deportations as factors hindering access to healthcare and use of services among migrant workers in Singapore [16–20]. Healthcare worker bias and suboptimal knowledge of migrant workers’ healthcare coverage and rights also created constraints [16]. Despite certain interventions, issues related to labour abuse and healthcare have continued to distress migrant workers [18, 19], suggesting inadequate policies and weak enforcement of existing legislation [18]. Housing provided for over 300,000 migrant workers consisted of factory-converted, temporary and purpose-built dormitories well away from the rest of the population. Overcrowding in dormitories is common, with up to 20 people sharing a room, yielding an effective living area of about 4.5m2 per worker [19]. Previous outbreaks among migrant workers involved air- or droplet-borne viruses—such as varicella-zoster and rubella and the 2019 measles outbreak—attributed to densely populated living environments of migrant workers [17, 21]. These outbreaks should have served as warning signs for the authorities.

In addition to isolation, stay-at-home notices and testing, the Singapore Ministry of Manpower issued advisories on timely payment of salaries, access to remittance services, delivery of food and essentials to dormitories and assurances that healthcare costs would be covered by the government and the employers. Earlier implementation of these strategies for migrant workers might have prevented the outbreaks in dormitories.

The current increase in the number of infections, therefore, appears to be driven by a combination of SDoH, including increased risks posed by overcrowded accommodation, limited access to healthcare and insurance, low and insecure wages, social marginalisation [22], poorly targeted government policies and weakly enforced existing legislation [16–18].

While broad measures enacted by the Government of Singapore at least partly address the SDoH identified above, amendments on 1 June 2020 to the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act of Singapore imposed strict movement controls on migrant workers living in dormitories through the authority of the ‘Controller of Work Passes’. These controls raise serious concerns about the workers’ rights and health [23]. Civil society organizations (CSOs) criticized policies and regulations related to payment of salaries during the pandemic, indicating apparent loopholes in enforcement and continued injustice faced by the migrant workers [24]. In Singapore, CSOs and trade unions worked closely with the government to assist with mitigation efforts [25].

Migrant workers are an under-documented pillar of Singapore’s economy, contributing to its key industries, maintaining industry competitiveness and creating jobs for Singaporeans [26, 27]. Global trade structures embodied in local Singaporean policy frameworks drive migrant workers into a negotiation disadvantage and undermine rights, leading to low-wage status [27]. If, however, provisions in the GCM were to be implemented and enforced, such measures would be well positioned to address issues related to the ‘migration cycle’, including debts incurred through the recruitment process and concerns about access to healthcare and equal rights compared to equivalent local workers.

South Korea: beyond the COVID-19 pandemic

The Government of South Korea (hereafter Korea) initially appeared to manage the pandemic well. However, the rapidly changing situation of migrant workers in Singapore forced Korea to develop urgent response mechanisms to address the impending risks. As of early September 2020, Korea reported a total of nearly 21,000 positive tests for COVID-19. Government statistical reports did not disaggregate the resident population from migrant workers. According to data from Statistics Korea and the Ministry of Justice, more than 863,000 migrants work in Korea, approximately 3.2% of its 27,154,000 total employed population (Korea’s total population is 51,630,000). Of migrant workers, 46.2% work in the manufacturing industry and 11% in construction, according to census data from 2019. Most of the migrant workers come from China, Vietnam and Thailand.

On 31 January 2020, just eleven days into the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea and long before the rise in infections in Singapore, the Ministry of Justice announced that it would not collect any information on undocumented migrants’ healthcare visits [28]. Between late April and early May, the government reasserted that undocumented migrants would receive free testing and treatment without the risk of being deported [29]. The government expanded existing language support for foreigners in the languages of major migrant groups, including guidance materials and hotlines, and introduced interest-free loans to pay for temporary accommodation for migrant workers requiring self-isolation [30]. Many local governments started distributing free facemasks and opened mobile testing centres at worksites and dormitories for migrant workers, including undocumented ones.

The government accorded priority for prevention and treatment of Korean nationals during the early phase of the outbreak while excluding those without National Health Insurance (NHI)—including migrant workers. Without NHI, migrant workers were unable to purchase face masks. Then, after sustained criticism from CSOs and trade unions, and in part, Singapore’s experiences with the outbreak, the Korean government eased restrictions on 20 April 2020 [31]. Free SARS-CoV-2 testing for migrant workers fell short of expectations due to their lack of awareness and lack of confidence in the government [32, 33]. Besides COVID-19 testing and treatment, basic healthcare for migrant workers remains limited, and it is especially difficult to obtain care for those without documentation [34, 35]. Even now, at the national level, Korea reserves its Emergency Disaster Relief Fund for Korean nationals’ households.

Due to its employer-centred design, the Employment Permit System (EPS) has further exacerbated migrant workers’ vulnerabilities during the pandemic. Employers confined many migrant workers to factories and dormitories as preventive measures to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 [36]. They forced others to take unpaid leave or laid them off without Employment Insurance benefits or other compensation for economic losses resulting from the pandemic [37, 38]. EPS operated as an authority that enabled discriminatory orders that restricted rights and limited migrants’ freedom of movement.

A pre-pandemic study identified potential barriers to healthcare such as language, lack of knowledge of local health services, health beliefs or attitudes and behaviours, communication barriers, and most importantly, financial barriers and time constraints [39]. These factors are likely structured by ‘upstream’ determinants, such as working conditions, employment security and social security, including access to healthcare. These conditions have been poor for many migrant workers in Korea since before the COVID-19 outbreak and present the government with a challenge [40].

Global economic inequalities play out in Korea due to wage differences based on the countries of origin and destination [41]. For example, despite social, economic and political inequalities experienced by the migrants compared to local residents, the average wage in Korea exceeds that of most other Asian countries, ensuring that Korea remains a major destination country for migrant workers [42]. Even so, the employers’ lack of knowledge and conformity with laws and the EPS that embodies the interests of Koreans further contribute towards inequalities [43]. Despite Korea having ratified the GCM (unlike Singapore and Brazil), wage parity with local residents has remained elusive.

Thus, in Korea, the COVID-19 pandemic reveals several legal, social and economic blind spots. These present opportunities for Korea to tackle the broader fundamental rights of migrant workers.

Brazil: a tale of origins and destinations

Brazil’s confirmed cases of COVID-19 per one million population are high compared to other countries [44]. As of early September 2020, the recorded daily average reached more than 1000 deaths, more than 4 million confirmed infections, low testing rates, growing numbers of cases in smaller cities and doubts about the reliability of the data released by the federal government. Political rumours and manoeuvrings predominated [45].

Brazil is both an origin and a destination country for migrant workers, including many low-wage migrant workers. By May 2020, 22,500 of the 3.5 million Brazilians residing overseas had returned home on flights financed by the Brazilian government [46]. Driven by socio-political, economic and environmental vulnerabilities in their home countries, almost 800,000 migrant workers from Haiti, Venezuela and Colombia live in Brazil [47]. Yet limited demographic and epidemiologic data on these subpopulations have hampered evidence-informed policymaking [48].

Following conflicts with the President, two health ministers resigned in as many months, throwing Brazil’s COVID-19 response into chaos. Despite the return of large numbers of citizens to Brazil, the government introduced basic screening programs at airports in Brazil only in April 2020, when the number of COVID-19 cases was already on the rise. Even then the government did not implement comprehensive screening or mandatory quarantine [49].

Documented migrant workers have guaranteed access to the Brazilian universal health system (SUS), as well as short-term financial help for unemployed and informal workers. Undocumented migrants have been systemically excluded from this financial assistance scheme. Lack of information, often aggravated by language barriers and discrimination, makes use of health services challenging [50, 51]. Brazil does not permit undocumented migrant workers to use public primary health care services, and testing and treatment at private clinics is prohibitively expensive.

Recent outbreaks of measles and tuberculosis in some municipalities that disproportionately affected migrant workers were associated with their precarious living and working conditions; these outbreaks should have served as warning signs for health authorities [47, 52]. Lack of monitoring and regulation of the migratory flow of workers in Brazil, both in relation to the greater risk of spreading SARS-CoV-2 and the economic and social vulnerability of this population, shows how Brazil has neglected public policy debates and action on migration policies.

Migrant workers in Brazil are frequently employed in industries that do not require specific qualifications and are often considered to be ‘unskilled’, with many working as informal workers in micro- small- and medium-sized enterprises [53, 54]. Despite being a significant population, ‘unskilled’ migrant workers are proportionally small within the Brazilian population, and their marginalized status diminishes the attention paid to their issues by stakeholders and undermines their bargaining power [55]. Moreover, recent changes to labour laws and lack of social dialogue between the state, industries and migrants reinforce a sustained attack by the political leadership on policy changes related to workers’ rights and undermine the financial and organizational capacity of trade unions [56]. This situation affects all workers in Brazil, but the impact on migrant workers, particularly undocumented ones, is likely to be harsher.

Following the COVID-19 outbreak, many migrant workers from Venezuela chose to return home rather than remain in Brazil [57, 58]. Information on the circumstances of Brazilian workers who returned home from abroad remains scarce. The current situation in Brazil indicates the need for constructive discussions between civil society groups and authorities with the aim of ensuring basic human rights, access to healthcare and social inclusiveness for migrant workers [50, 54].

Focussing the lens

Applying our social determinants of health lens, we argue that overcrowded dormitories in Singapore, insecure living and working environments in Brazil, and precarious working conditions in Korea are likely to have increased exposure of migrant workers to SARS-CoV-2. Poor social protection, including restrictions related to healthcare, made it obligatory that Singapore and Korea implement special provisions during the COVID-19 outbreak; Brazil, plagued by poor leadership, mounted an inadequate response. Neglect of ‘red flags’—alerts that should have been apparent based on experience from previous outbreaks in Singapore and Brazil—may have limited opportunities for prevention and effective mitigation of the health crisis. Our analysis demonstrates that economic and social marginalization, language barriers, lack of information, lack of legal protection and fear of deportation comprise widespread direct and indirect barriers to healthcare in all three settings. We identified, in relation to Singapore and Brazil, a scarcity of data on migrant workers from government agencies and academic research. This has undermined opportunities for evidence-informed policymaking based on quality translational research focussed on the SDoH and health policy [59].

Unwarranted and negative attitudes expressed towards migrant workers in communities create a perception that migrant workers may have a higher chance of carrying infections compared to local residents and become a burden on health services [7], as in Korea. Such negative attitudes may intensify a lack of trust among migrant workers, governments and local citizens.

Thus, many SDoH identified in studies before the COVID-19 outbreak have been realized, if not exacerbated by the pandemic. Efforts of the Korean and Singapore governments demonstrate potential for effective action and emphasize a need for long-term sustainable changes to address inequities that undermine the health and wellbeing of migrant workers. Necessary changes, we argue, include universal and equitable healthcare, social safety nets and labour rights for migrant workers. Addressing labour rights will require a collective response to reform labour markets by international organizations and the states. Organizations such as the International Labour Organization, tasked with the protection of all workers including migrant workers, face challenges in balancing the demands from sovereign states over immigration restrictions with the economic need for flexible, mobile labour forces [60].

Thus, it is imperative for those in the health to sector support political measures to adopt a broader, whole-of-government approach to revising regulations and policies on health and employment, closing existing loopholes and developing mechanisms for better implementation, as called for in the GCM. By implication, this means reducing structural determinants as part of addressing the health needs of migrant workers.

Singapore abstained from voting on the GCM, while Brazil withdrew from it less than two weeks after the incumbent president assumed power in early 2019. These actions demonstrate the reluctance of both countries to implement GCM recommendations. Highly restrictive and discriminatory laws, such as those recently introduced in Singapore, show how vulnerable such agreements are to domestic political agendas and local constraints [23]. While the GCM calls on governments to enact and enforce laws related to labour rights violations and to cooperate with the private sector to prevent labour abuse and exploitation, there are few incentives or benefits for governments and companies to do so, particularly within inequitable global trade structures, including global labour supply chains. Global trade structures are manifested through predominant economic ideologies that prioritize market forces, creating the circumstances in which low-wage labour and poor working conditions can thrive. Therefore, real change in policies towards migrant workers and norm-building among states to improve conditions for migrant workers will require committed political engagement and advocacy from civil societies, trade unions, human rights groups and migrant workers themselves.

Conclusion

The circumstances of the migrant workers during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic expose social weaknesses and demonstrate how the public health crisis is exacerbated by those weaknesses. It highlights the need to frame public health policy in ways that show structural determinants—inequality, poverty and lack of rights—as fundamental to health as governments manage prevention and mitigation efforts during a crisis. We draw four key conclusions from this analysis:

the SDoH framework, and recognizing migration within this framework, is necessary for a full understanding of and comprehensive approach to managing the effects of health crises on migrant workers;

the ‘upstream’ application of the SDoH approach requires a broader range of political and economic reforms to address the health, economic and social inequalities that migrant workers face;

evidence-informed public health policymaking, through wide application of translational research, is necessary for successful application of a SDoH approach in health crises;

the underlying determinants of health vulnerabilities are rooted in fundamental economic inequalities that drive global capital and labour.

This prompts the question of why there are low-wage workers at all.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Mr Alex Au (Vice-President, Transient Workers Count Too), Ms Desiree Leong (Casework Executive, Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics) and Ms Kimberly Price (linguistics specialist).

Biographies

Amarasinghe Arachchige Don Nalin Samandika Saparamadu

MBBS, DipIBLM, is a General Practitioner at Doctor Anywhere Pte. Ltd., Singapore.

Albie Sharpe

MHID, Ph.D., is a Lecturer at the School of Public Health, The University of Technology Sydney, Australia.

Sun Kim

M.S., Ph.D., is Director, Health Policy Research Center, People’s Health Institute, Seoul, South Korea.

Bruna Ligia Ferreira Almeida Barbosa

MNS, Ph.D., Postgraduate Program of Collective Health, Federal University of Espirito Santo, Vitoria, Brazil.

Adrian Pereira

B. Eng, is Executive Director of the North South Initiative, Selangor, Malaysia.

Author contributions

AADNSS, AS and AP wrote the initial manuscript with the case study of Singapore. SK and BLFAB wrote the case studies of South Korea and Brazil, respectively. All authors worked together on the revisions, shared in the design, literature review and the final manuscript.

Funding

SK acknowledges support by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2017R1D1A1B03031898).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: Due to an unfortunate oversight during the copy editing a sentence in paragraph ‘South Korea: beyond the COVID‑19 pandemic’ has been given erroneously.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/1/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1057/s41271-021-00305-x

References

- 1.International Organization for Migration. International migration law - glossary on migration. Geneva: International Organization for Migration; 2019. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- 2.Ross M, Bateman N. Meet the low-wage workforce. Washington, D.C.: Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings; November 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/201911_Brookings-Metro_low-wage-workforce_Ross-Bateman.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2020.

- 3.World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. In: Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization, Geneva. 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43943/9789241563703_eng.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2020.

- 4.Kickbusch I. The political determinants of health—10 years on. BMJ. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Human Rights. The International Convention on Migrant Workers and its Committee. New York and Geneva: United Nations; 2005. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet24rev.1en.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2020.

- 6.Global forum on migration development. 2020. https://www.gfmd.org. Accessed 1 June 2020.

- 7.Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. The Lancet. 2018 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organisation. Promoting the health of refugees and migrants. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/publications/promoting-health-of-refugees-migrants-framework-and-guiding-principles.pdf?sfvrsn=289d4ae6_1. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- 9.Castaneda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, et al. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakerveld J, Mackenbach J. The upstream determinants of adult obesity. Obes Facts. 2017;10(3):216–222. doi: 10.1159/000471489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharmal N, Derose KP, Felician M, et al. Understanding the upstream social determinants of health. In: Prepared for the RAND Social Determinants of Health Interest Group. RAND. 2015. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1000/WR1096/RAND_WR1096.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2021.

- 13.Zimmerman C, Kiss L. Human trafficking and exploitation: a global health concern. PLoS Med. 2017 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumagbas LB, Coleman HLS, Bunders J, Pariente A, Belonje A, de CockBuning T. Non-communicable diseases in Indian slums: re-framing the Social Determinants of Health. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1438840. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1438840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths J. Singapore had a model coronavirus response, then cases spiked. What happened? CNN. 19 April. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/18/asia/singapore-coronavirus-response-intl-hnk/index.html. Accessed 21 April 2020.

- 16.Ang JW, Koh CJ, Chua BWB, et al. Are migrant workers in Singapore receiving adequate healthcare? A survey of doctors working in public tertiary healthcare institutions. Singapore Med J. 2019 doi: 10.11622/smedj.201910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadarangani SP, Lim PL, Vasoo S. Infectious diseases and migrant worker health in Singapore: a receiving country’s perspective. J Travel Med. 2017 doi: 10.1093/jtm/tax014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornatowksi G. Caught up in policy gaps: distressed communities of South-Asian migrant workers in Little India. Singapore Community Dev J. 2017 doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsw051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Transient Workers Count Too. Home page. Singapore: TWC2; 2020. https://twc2.org.sg. Updated 18 April 2020; Accessed 19 April 2020.

- 20.Harrigan NM, Koh CY, Amirrudin A. Threat of deportation as proximal social determinant of mental health amongst migrant workers. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pung R, Lee TH, Peh X, et al. Measles ring vaccination in dormitories: an outbreak containment measure and simulation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3502369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubdy R, McKay SL. ‘Foreign workers’ in Singapore: conflicting discourse, language politics and the negotiation of immigrant identities. Int J Sociol Lang. 2013 doi: 10.1515/ijsl-2013-0036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work passes) (Amendment) Regulations 2020 (Singapore). 1 June 2020. S427.

- 24.The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Protecting human rights during and after the COVID-19 Joint questionnaire by Special Procedure mandate holders. Response to joint questionnaire of special procedures. Geneva: UN Human Rights; 10 June 2020; https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/SP/COVID/NGOs/twc2_ohchr_sr_20200610d.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- 25.Wong C. Coronavirus: NGOs step in to help migrant workers at smaller housing facilities. Straitstimes. 24 April; https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/coronavirus-ngos-step-in-to-help-migrant-workers-at-smaller-housing-facilities. Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- 26.Co C. Reducing migrant worker population will affect Singapore's competitive edge, lead to higher costs: Industry groups. 24 April 2020; https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/reducing-migrant-worker-affect-singapore-economy-higher-costs-12774646. Updated 28 May 2020; Accessed 27 Jan 2021.

- 27.Lim J, Yuan YJ. The Big Read: undervalued and underpaid, Singapore’s essential services workers deserve better. 13 June 2020; https://www.todayonline.com/big-read/big-read-singapores-under-valued-essential-services-workers-how-pay-them-what-they-deserve. Updated 22 June 2020; Accessed 20 April 2020.

- 28.Ministry of Justice (KR). Undocumented foreign nationals can also get an infection disease check-up without any fear. Gwacheon: Ministry of Justice (KR). 2020; http://www.moj.go.kr/bbs/immigration/214/519175/artclView.do. Updated 31 January 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020]. (in Korean)

- 29.Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (KR). Crackdown suspension and COVID-19 testing support on undocumented foreign nationals … “Inclusive quarantine measures towards blind spots”. Seoul: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (KR). 2020; http://www.korea.kr/news/policyNewsView.do?newsId=148872050. Updated 1 May 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020. (in Korean)

- 30.Ministry of Employment and Labor (KR). Strengthen immigration control for foreign workers (E-9) returning from vacation. Sejong: Ministry of Employment and Labor (KR). 2020; http://www.moel.go.kr/news/enews/report/enewsView.do?news_seq=10948. Updated 4 May 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020. (in Korean)

- 31.Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (KR). (4.19) Regular briefing of Safety Countermeasure Headquarters on COVID-19. Seoul: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (KR). 2020; http://www.korea.kr/news/pressReleaseView.do?newsId=156386021. Updated 19 April 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020. (in Korean)

- 32.JoongAng Ilbo. “Be reluctant to get testing in fear of identity exposure”; 390,000 undocumented foreign nationals are in blind spots of quarantine. Seoul: JoongAng Ilbo.2020; https://news.joins.com/article/23774213. Updated 12 May 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020. (in Korean)

- 33.The Hankyoreh. No mask, no funding… migrant workers in the COVID-19 crisis. Seoul: The Hankyoreh. 2020; .http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/rights/949182.html. Updated 13 June 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020 (in Korean)

- 34.Byung Woon L, Zoon KK. Study on conditions and problems of the medical services ( Health and Medical Care) for the foreign workers. Han Yang Law Rev. 2010;31:323–352. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Na S, Saori H, Kyu JC. Undocumented migrants health management and experience of health care services: using in-depth interviews and grounded theory. Multicult Peace. 2009;13(1):1–33. doi: 10.22446/mnpisk.2019.13.1.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.OhmyNews. Two months in de facto confinement... Migrant workers say “the employers handle us like COVID-19 propagators”. Seoul: OhmyNews; 2020; http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0002624384. Updated 23 March 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020. (in Korean)

- 37.KBS NEWS. Migrant workers say, “use us when you need us, and throw us away if you don't need us… pay the Emergency Disaster Relief Fund”. Seoul: KBS. 2020. http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=4455787 . Updated 27 May 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020. (in Korean)

- 38.The Hankyoreh. Migrant workers forced to go on unpaid leave as manufacturers shut down due to COVID-19. Seoul: The Hankyoreh. 2020; http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/943692.html. Updated 5 May 2020; Accessed 18 June 2020.

- 39.Kim S. The conception and factors that affect the utilization of health care services among foreign migrant workers in Korea. J Multi-Cult Contents Stud. 2015 doi: 10.15400/mccs.2015.04.18.255.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Republic of Korea NGO Alternative Report to the UN committee on the elimination of racial discrimination. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 14 Dec 2018. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KOR/INT_CERD_NGO_KOR_32854_E.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2020.

- 41.Seol D. The citizenship of foreign workers in South Korea. Citizsh Stud. 2012 doi: 10.1080/13621025.2012.651408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.United Nations, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) Assessing Implementation of the Global Compact for Migration. Asia-Pacific Migration Report 2020. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/APMR2020_FullReport.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2021

- 43.Hyun-ju O. Migrant workers denounce 'modern-day slavery' in Korea. Seoul; The Korea Herald. 21 Oct 2020. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20201021000830. Updated 21 October 2020; Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

- 44.Castro MC, Kim S, Barberia L, et al. Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID-19 spread in Brazil. Science. 2021;372(6544):821–826. doi: 10.1126/science.abh1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolsonaro and the political crisis in the Planalto Palace. Estado de Minas News. 9 May 2020. https://www.em.com.br/app/noticia/politica/2020/05/09/interna_politica,1145770/bolsonaro-e-a-crise-politica-construida-no-palacio-do-planalto.shtml.

- 46.How many Brazilians live abroad? Uol News. 22 June 2018. https://noticias.uol.com.br/ultimas-noticias/deutschewelle/2018/06/22/quantos-brasileiros-vivem-fora-do-pais.htm. Accessed 1 June 2020.

- 47.Martin D, Goldberg A, Silveira C. Immigration, refuge and health: sociocultural analysis in perspective. Saude Soc. 2018 doi: 10.1590/S0104-12902018170870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandes JM, Ruediger MA, Spohr AP, Oliveira W. Immigration data in Brazil: fragmentation and lack of coordination of databases and its challenges to migration policy. FGV DAPP 2018. http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/25942?show=full.

- 49.Alvim M. Coronavirus: airport temperature measurement is new chapter in dispute between states and federal government. BBC. 2020 Mar 27. https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-52059042. Accessed 1 June 2020.

- 50.Granada D, Carreno I, Ramos N, et al. Debating health and migrations in a context of intense human mobility. Interface. 2017 doi: 10.1590/1807-57622016.0626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brazilian Government. Request of the Emergency Aid—COVID 19. Brazil; 2020. https://www.gov.br/pt-br/servicos/solicitar-auxilio-emergencial-de-r-600-covid-19. Accessed 6 June 2020.

- 52.Brazilian Federal Senate. CBH will discuss the immigrants’ conditions in Brazil. Brazil: Federal Senate. 3 Feb 2020. https://www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/materias/2020/02/03/cdh-vai-debater-condicao-de-imigrantes-no-brasil. Accessed 1 June 2020.

- 53.International Organization for Migration. Guidance on Protection for Migrant Workers during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Brazil; IOM. August 2020. https://brazil.iom.int/sites/default/files/Publications/2020_icc_guidance_for_migrant_workers_02_1.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- 54.Fernandes D, Baeninger R, et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the international migration in Brazil. Campinas, SP: Núcleo de Estudos de População “Elza Berquó”, Nepo/Unicamp; September 2020. https://www.nepo.unicamp.br/publicacoes/livros/impactos_pandemia/COVID%20NAS%20MIGRAÇÕES%20INTERNACIONAIS.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 202.1 (in Portugese)

- 55.Teixeira LB. Brazil has few immigrants—Foreign presence in the country today is one of the smallest in history and in the world. Uol News. 2020 Aug 18. https://www.uol/noticias/especiais/imigrantes-brasil-venezuelanos-refugiados-media-mundial.htm#frases-1. Accessed 28 June 2021.

- 56.Tomazelli I. Government hinders payment of union contribution. Uol. 03 Mar 2019. https://economia.uol.com.br/noticias/estadao-conteudo/2019/03/03/governo-dificulta-pagamento-de-contribuicao-sindical.htm. Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

- 57.Migration Data Portal. Migration data relevant for the COVID-19 pandemic. Berlin;Migration Data Portal. 11 January 2021. https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/migration-data-relevant-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

- 58.Jubilut LL, Silva JCJ. COVID-19 at the Brazil-Venezuela borders: the good, the bad and the ugly. London: Open Democracy. 18 June 2020. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/pandemic-border/covid-19-brazil-venezuela-borders-good-bad-and-ugly/. Accessed 5 Jan 2021.

- 59.van Schalkwyk MC, Harris M. Translational health policy: towards an integration of academia and policy. J R Soc Med. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0141076817735692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maul D. The International Labour Organization: 100 years of global social policy. Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH; 2019. [Google Scholar]