Key Points

Question

What are the trends and patterns of regional and socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular risk factors in Canada from 2005 to 2016?

Findings

This survey study of 670 000 adults found a significant increase in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity but a significant decrease in the prevalence of current smoking, with prevalence rates varying widely across health regions. In addition to obesity among men, persistent absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities were observed for all risk factors.

Meaning

These findings suggest that geographic and socioeconomic gaps should be considered and addressed in future cardiovascular health strategies in Canada.

This survey study investigates the temporal trends, regional variations, and socioeconomic disparities in major cardiovascular risk factors in Canada from 2005 to 2016.

Abstract

Importance

Cardiovascular disease remains the second leading cause of death in Canada. Monitoring and tracking the trends and disparities in major cardiovascular risk factors could provide benchmarks for future cardiovascular health strategies.

Objective

To investigate the temporal trends, regional variations, and socioeconomic disparities in major cardiovascular risk factors in Canada from 2005 to 2016.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This repeated cross-sectional survey study included adults aged 20 years and older from 6 Canadian Community Health Survey cycles between 2005 and 2016. Cardiovascular risk factors included hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking. Socioeconomic status was measured using equivalized household income. Data analysis was performed from September 2019 to April 2020.

Exposures

A total of 112 health regions and socioeconomic status.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking by year; health regions; and socioeconomic status. Absolute numbers were rounded to base 100 for confidentiality purposes, and percentages were based on weighted numbers. Slope index of inequality (SII) and relative index of inequality (RII) were calculated to assess absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities, respectively.

Results

A total of 670 000 respondents (329 000 [49.1%] men; 341 000 [50.9%] women) aged 20 years and older from 6 survey cycles were enrolled for this study. The largest age group was those aged 40 to 59 years (eg, 2005 cycle: 40.2% [95% CI, 39.9%-40.6%]). In the 2015/2016 cycle, the overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence rates of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking were 20.7% (95% CI, 20.4%-21.1%), 7.2% (95% CI, 7.0%-7.5%), 20.1% (95% CI, 19.7%-20.6%), and 17.8% (95% CI, 17.4%-18.2%), respectively. From 2005 to 2016, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (eg, prevalence of diabetes in both sexes, 2005: 5.8% [95% CI, 5.6%-6.0%]; 2015/2016: 7.2% [95% CI, 7.0%-7.5%]; P < .001) but a significant decrease in the prevalence of current smoking (both sexes, 2005: 22.1% [95% CI, 21.7%-22.5%]; 2015/2016: 17.8% [95% CI, 17.4%-18.2%]; P < .001). The prevalence of all the risk factors varied widely across health regions (eg, obesity, Vancouver Health Service Delivery Area: 6.7% [95% CI, 4.5%-9.0%]; Miramichi Area: 36.8% [95% CI, 27.3%-46.3%]). In addition to obesity among men, all risk factors tended to be more common among those with lower income (eg, prevalence of hypertension in both sexes, 2015/2016, lowest income group: 23.2% [95% CI, 22.4%-24.0%]; highest income group: 18.4% [95% CI, 17.7%-19.1%]). The SII and RII indicated consistent absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities in hypertension, diabetes, and current smoking over time (eg, RII for hypertension in both sexes, 2005: 1.25; 95% CI, 1.18-1.33; 2015/2016: 1.34; 95% CI, 1.26-1.43). However, the phenomenon of absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities in obesity was only observed among women (eg, RII for 2015/2016 for obesity in women; 1.74 (95% CI, 1.56-1.93); men: 1.09; 95% CI, 0.99-1.21).

Conclusions and Relevance

During the study period, the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity significantly increased, while the prevalence of current smoking significantly decreased. Geographic and socioeconomic gaps should be considered and addressed in future interventions and policies targeted at reducing these cardiovascular risk factors in Canada.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the second leading cause of death in Canada and has imposed a huge economic burden on Canadian health care systems.1,2 Convincing evidence demonstrates that management of major risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking, could effectively reduce cardiovascular events and mortality.3,4,5 Unfortunately, besides smoking, a continuing increase in the prevalence of these cardiovascular risk factors has been reported in the Canadian population between 1994 and 2005.6 Moreover, regional variations in the prevalence and treatment of these risk factors make this situation even more complicated.7 To reverse these unfavorable trends, several prevention strategies, such as the Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program and Canadian Hypertension Education program, have been launched and widely implemented.8,9 However, the lack of nationally representative data investigating the latest trends in hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking makes it difficult to assess the impact of prevention programs on the Canadian population. Additionally, recent studies suggest that in Canada, socioeconomic inequalities in health may be widening over time.10,11 Monitoring and tracking socioeconomic disparities in hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking could provide benchmarks for future health strategies; however, less is known about the secular trends in socioeconomic inequalities with regard to these major cardiovascular risk factors in Canada. Thus, the aims of this study were to provide an update of the secular trends in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking at the national and regional levels and to estimate relative and absolute socioeconomic inequalities in these major cardiovascular risk factors in Canada between 2005 and 2016.

Methods

Data Sources

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), conducted by Statistics Canada, has been a nationally representative cross-sectional survey study since 2000. Details about the design and conduct of the CCHS are available online.12 In brief, using consistent, multistage, stratified cluster sampling strategies, a nationally representative sample was selected for each survey in 1-year or 2-year cycles. The survey excluded people living on Indian reserves or Crown lands, people living in institutions, full-time members of the Canadian military, and residents of certain remote regions (all representing <3% of the population). For the current analysis, we included adults aged 20 years and older from the latest 6 cycles (done in 2005, 2007/2008, 2009/2010, 2011/2012, 2013/2014, and 2015/2016) of the CCHS. Ethical approval of the CCHS was obtained from the relevance policy committees at Statistics Canada, and all respondents provided written informed consent. Per Statistics Canada, additional institutional review board approval for this study was not needed. This study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline.

Measures

Our study focused on 4 major cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking. For all surveys, the ascertainment of hypertension was based on questions about whether a respondent recalled receiving a physician diagnosis of hypertension or taking medications for hypertension.13 Similarly, diabetes was determined by questions about whether a respondent recalled receiving a physician diagnosis of diabetes or taking medications for diabetes. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 30 or greater according to clinical guidelines14; BMI was calculated using self-reported height and weight. Women who were pregnant during the survey were excluded from the analysis of obesity. Current smoking was defined as now smoking cigarettes occasionally or daily and having smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime.15

Health regions refer to administrative areas divided by Canadian provincial government to administer and deliver health care services to all residents. Because the boundaries change over time,16 health regions were combined to ensure stable units of analysis over the period 2005 to 2016, reducing the number of areas analyzed from 112 to 105 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Additionally, as suggested by Statistics Canada,16 3 neighboring health regions in Saskatchewan, which have small populations, were combined to avoid potential poor data quality (eTable 2 in the Supplement). For simplicity, combined areas are referred to as health regions throughout.

Socioeconomic status was measured using equivalized household income, which is defined as total annual household income divided by the square root of household size.17,18 To ensure a consistent comparison over the period 2005 to 2016, equivalized household income was then categorized into quartiles in each survey cycle.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp) and R version 3.6.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Statistical significance was met with 2-tailed P < .05. For all surveys, sampling weights provided by Statistics Canada were applied to obtain population estimates. Bootstrap methods provided by Statistics Canada were used to account for complex survey design. Absolute numbers were rounded to base 100 for confidentiality purposes according to Statistics Canada data release policies. Percentages were based on weighted numbers. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was calculated by direct standardization to the 2006 Canada Census population using the joint age (10-year interval) and sex groups. Temporal trends in prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors were evaluated by multivariable Poisson regression analysis, adjusting for age and sex.19,20 P values for trend were then measured using the contrast postestimation command in Stata.

We examined absolute socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular risk factors with the slope index of inequality (SII) and relative socioeconomic inequalities with the relative index of inequality (RII).21,22,23 To calculate the SII and RII, we first transformed socioeconomic status into cumulative rank probabilities (ridit scores) ranging from 0 (highest) to 1 (lowest).22 Then, we used multivariable Poisson regression models, adjusting for age and sex, to estimate the association between the ridit scores and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. The RII was derived from the regression models, and the SII was obtained using marginal effects and the nlcom postestimation commands in Stata. Temporal trends in the SII and RII were assessed by adding the interaction term between the ridit scores and survey circles into the regression models.24 P values for trend were then calculated using the contrast postestimation command in Stata.

Results

A total of 670 000 respondents (329 000 [49.1%] men; 341 000 [50.9%] women) aged 20 years and older from 6 survey cycles were enrolled for this study. The largest age group were those aged 40 to 59 years (eg, 2005 cycle: 40.2% [95% CI, 39.9%-40.6%]). The sample size and the distribution of study sample by sex and age group in each survey are shown in Table 1. The percentage of missing values for each cardiovascular risk factor (ie, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking) is also shown in Table 1. Respondents who had missing values were excluded from the respective analysis of each cardiovascular risk factor.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample.

| Characteristic | Respondents, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2007/2008 | 2009/2010 | 2011/2012 | 2013/2014 | 2015/2016 | |

| Sample sizea | 116 600 | 117 400 | 110 300 | 111 800 | 115 000 | 98 900 |

| Weighted populationa | 23 778 300 | 24 651 000 | 25 380 400 | 26 098 300 | 26 833 900 | 27 462 100 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 49.0 (49.0-49.0) | 49.0 (49.0-49.1) | 49.1 (49.1-49.1) | 49.1 (49.1-49.1) | 49.1 (49.1-49.1) | 49.1 (49.0-49.2) |

| Women | 51.0 (51.0-51.0) | 51.0 (51.0-51.0) | 50.9 (50.9-50.9) | 50.9 (50.9-50.9) | 50.9 (50.9-50.9) | 50.9 (50.8-51.0) |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 20-39 | 36.6 (36.4-36.9) | 36.2 (36.0-36.5) | 35.3 (35.0-35.6) | 35.3 (35.0-35.6) | 35.1 (34.8-35.4) | 34.6 (34.3-34.9) |

| 40-59 | 40.2 (39.9-40.6) | 39.9 (39.5-40.3) | 39.7 (39.2-40.2) | 38.1 (37.6-38.6) | 37.4 (36.9-37.9) | 36.6 (36.2-37.0) |

| 60-79 | 19.5 (19.3-19.7) | 20.1 (19.8-20.4) | 21.0 (20.7-21.4) | 22.4 (22.0-22.8) | 23.3 (22.9-23.7) | 24.6 (24.3-24.9) |

| ≥80 | 3.7 (3.6-3.8) | 3.8 (3.7-3.9) | 4.0 (3.9-4.1) | 4.2 (4.0-4.3) | 4.2 (4.1-4.4) | 4.2 (4.0-4.4) |

| Missing valuesb | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.20 (0.16-0.25) | 0.30 (0.26-0.35) | 0.23 (0.19-0.28) | 0.28 (0.23-0.34) | 0.27 (0.22-0.33) | 0.44 (0.38-0.52) |

| Diabetes | 0.09 (0.06-0.12) | 0.11 (0.08-0.14) | 0.05 (0.04-0.07) | 0.10 (0.08-0.14) | 0.12 (0.09-0.17) | 0.14 (0.10-0.19) |

| Obesity | 3.20 (3.05-3.36) | 5.44 (5.22-5.67) | 5.17 (4.96-5.39) | 5.15 (4.93-5.38) | 5.31 (5.08-5.56) | 6.54 (6.28-6.81) |

| Current smoking | 0.54 (0.44-0.66) | 0.27 (0.22-0.31) | 0.29 (0.25-0.35) | 0.38 (0.32-0.45) | 0.38 (0.33-0.45) | 0.29 (0.25-0.35) |

Numbers are rounded to base 100 for confidentiality purposes according to Statistics Canada data release policies. Percentages are based on weighted numbers.

Participants who responded “Don’t know,” “Refusal,” or “Not stated” to the questions were regarded as having missing values and thus not included in respective analysis. For obesity, participants with missing values included women who are pregnant.

Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in 2015/2016 Cycle

The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of each cardiovascular risk factor in 2015/2016 overall and by sex and age group was shown in Table 2 and eTable 3 in the Supplement. The overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking was 20.7% (95% CI, 20.4%-21.1%), 7.2% (95% CI, 7.0%-7.5%), 20.1% (95% CI, 19.7%-20.6%), and 17.8% (95% CI, 17.4%-18.2%), respectively; all risk factors tended to be higher among men. Additionally, as expected, the adjusted prevalence of hypertension and diabetes increased substantially with age. By contrast, the adjusted prevalence of obesity and current smoking was lowest in those aged 80 years or older. Notably, 14.8% (95% CI, 14.4%-15.1%) of the respondents reported an accumulation of at least 2 cardiovascular risk factors.

Table 2. Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Overall and by Sex.

| Risk factor | Respondents, % (95% CI) | P value | Direction of trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2007/2008 | 2009/2010 | 2011/2012 | 2013/2014 | 2015/2016 | |||

| Both sexes | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 19.1 (18.8-19.4) | 20.0 (19.7-20.3) | 20.3 (19.9-20.7) | 20.3 (19.9-20.6) | 20.1 (19.7-20.4) | 20.7 (20.4-21.1) | <.001 | Increase |

| Diabetes | 5.8 (5.6-6.0) | 6.7 (6.5-7.0) | 6.9 (6.7-7.2) | 6.9 (6.6-7.1) | 7.0 (6.8-7.3) | 7.2 (7.0-7.5) | <.001 | Increase |

| Obesity | 16.1 (15.8-16.5) | 17.3 (16.9-17.6) | 18.2 (17.8-18.6) | 18.6 (18.1-19.0) | 19.7 (19.2-20.1) | 20.1 (19.7-20.6) | <.001 | Increase |

| Current smoking | 22.1 (21.7-22.5) | 22.1 (21.7-22.5) | 20.8 (20.4-21.3) | 20.7 (20.2-21.2) | 19.2 (18.8-19.7) | 17.8 (17.4-18.2) | <.001 | Decrease |

| ≥2 Risk factors | 12.5 (12.2-12.8) | 13.7 (13.4-14.0) | 14.2 (13.9-14.6) | 14.3 (13.9-14.6) | 14.4 (14.0-14.7) | 14.8 (14.4-15.1) | <.001 | Increase |

| Men a | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 18.8 (18.3-19.2) | 19.9 (19.5-20.4) | 20.6 (20.0-21.1) | 20.9 (20.4-21.4) | 21.6 (21.0-22.1) | 22.1 (21.5-22.6) | <.001 | Increase |

| Diabetes | 6.6 (6.3-6.9) | 7.6 (7.3-8.0) | 8.2 (7.8-8.6) | 7.7 (7.3-8.0) | 8.1 (7.7-8.5) | 8.3 (7.9-8.6) | <.001 | Increase |

| Obesity | 17.2 (16.6-17.7) | 18.3 (17.8-18.8) | 19.6 (19.0-20.2) | 19.6 (19.0-20.2) | 21.2 (20.5-21.9) | 21.6 (21.0-22.3) | <.001 | Increase |

| Current smoking | 24.1 (23.6-24.7) | 24.8 (24.2-25.4) | 23.7 (23.0-24.3) | 23.4 (22.7-24.1) | 22.4 (21.7-23.1) | 20.4 (19.8-21.0) | <.001 | Decrease |

| ≥2 Risk factors | 13.2 (12.8-13.6) | 14.7 (14.3-15.2) | 15.7 (15.1-16.2) | 15.5 (14.9-16.1) | 16.4 (15.8-17.0) | 16.7 (16.2-17.3) | <.001 | Increase |

| Women a | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 19.3 (18.9-19.7) | 19.9 (19.5-20.4) | 19.8 (19.4-20.3) | 19.6 (19.1-20.1) | 18.6 (18.1-19.0) | 19.3 (18.8-19.8) | .015 | Decrease |

| Diabetes | 5.1 (4.9-5.3) | 5.9 (5.7-6.2) | 5.8 (5.6-6.1) | 6.2 (5.9-6.6) | 6.1 (5.8-6.4) | 6.3 (6.0-6.7) | <.001 | Increase |

| Obesity | 15.1 (14.6-15.5) | 16.2 (15.8-16.7) | 16.8 (16.3-17.3) | 17.5 (17.0-18.1) | 18.2 (17.6-18.7) | 18.7 (18.1-19.3) | <.001 | Increase |

| Current smoking | 20.1 (19.6-20.6) | 19.5 (19.0-20.0) | 18.1 (17.6-18.6) | 18.2 (17.6-18.8) | 16.1 (15.6-16.7) | 15.3 (14.7-15.8) | <.001 | Decrease |

| ≥2 risk factors | 11.8 (11.5-12.2) | 12.6 (12.2-13.0) | 12.8 (12.4-13.3) | 13.1 (12.6-13.5) | 12.5 (12.1-12.9) | 12.9 (12.4-13.4) | .005 | Increase |

Sex comparisons are only adjusted for age.

Trend Analyses

From 2005 to 2016, there was a statistically significant increase in the overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (eg, prevalence of diabetes in both sexes, 2005: 5.8% [95% CI, 5.6%-6.0%]; 2015/2016: 7.2% [95% CI, 7.0%-7.5%]; P < .001), but a statistically significant decrease in the overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of current smoking (both sexes, 2005: 22.1% [95% CI, 21.7%-22.5%]; 2015/2016: 17.8% [95% CI, 17.4%-18.2%]; P < .001). Temporal trends in the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors by sex and age group are shown in Table 2 and eTable 3 in the Supplement. Between 2005 and 2016, the adjusted prevalence of hypertension significantly increased among men aged 40 to 59 years, 60 to 79 years, and 80 years and older as well as among women aged 80 years and older, but it slightly decreased among women aged 40 to 59 years and 60 to 79 years; the adjusted prevalence of diabetes significantly increased among men aged 40 to 59 years, 60 to 79 years, and 80 years and older as well as among women in the same age groups; the adjusted prevalence of obesity significantly increased among men in all age groups and among women aged 20 to 39 years, 40 to 59 years, and 60 to 79 years; and the adjusted prevalence of current smoking significantly declined among men aged 20 to 39 years, 40 to 59 years, and 80 years and older as well as among women in all age groups (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Regional Variations

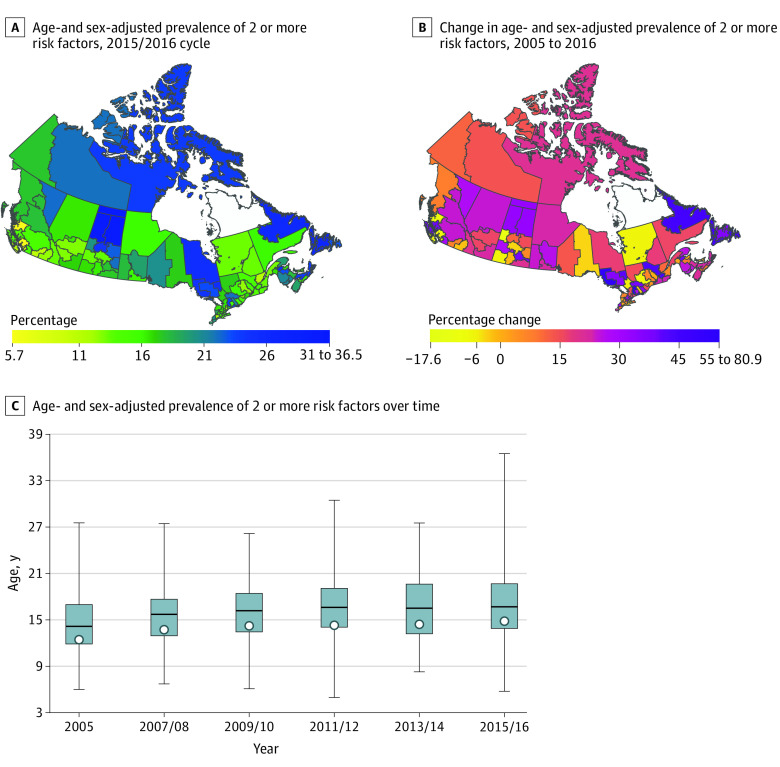

In 2015/2016, the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, current smoking (eFigures 1-4 in the Supplement), and 2 or more cardiovascular risk factors (Figure 1) varied widely across health regions. For hypertension, the health region–level age- and sex-adjusted prevalence ranged from 12.7% (95% CI, 10.6%-14.9%) in the North Shore/Coast Garibaldi Health Service Delivery Area to 31.0% (95% CI, 23.2%-38.7%) in the Mamawetan/Keewatin/Athabasca Regional Health Authorities; for diabetes, it ranged from 3.9% (95% CI, 2.9%-4.8%) in the Okanagan Health Service Delivery Area to 15.3% (95% CI, 8.7%-21.9%) in the Mamawetan/Keewatin/Athabasca Regional Health Authorities; for obesity, it ranged from 6.7% (95% CI, 4.5%-9.0%) in the Vancouver Health Service Delivery Area to 36.8% (95% CI, 27.3%-46.3%) in the Miramichi Area; for current smoking, it ranged from 11.0% (95% CI, 7.8%-14.2%) in the Richmond Health Service Delivery Area to 62.4% (95% CI, 57.4%-67.4%) in Nunavut; and for 2 or more cardiovascular risk factors, it ranged from 5.7% (95% CI, 3.8%-7.6%) in the Eastern Regional Health Authority to 36.5% (95% CI, 28.0%-45.0%) in the Mamawetan/Keewatin/Athabasca Regional Health Authorities.

Figure 1. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of 2 or More Cardiovascular Risk Factors.

A and B, 2 health regions (ie, Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres Cries de la Baie James) are blank because of missing data. C, The bottom border, middle line, and top border of the boxes indicate the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, respectively, across all health regions; the whiskers indicate the full range across all health regions; and the circles indicate the national-level prevalence rate.

Although national age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and 2 or more cardiovascular risk factors increased between 2005 and 2016 (Table 2), there were 26, 24, 10, and 19 health regions, respectively, that experienced a decline in the prevalence rates over the same period. Conversely, although national age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of current smoking declined between 2005 and 2016 (Table 2), 9 health regions experienced an increase over this period (eg, Campbellton area: 2005, 20.9% [95% CI, 14.9%-26.9%]; 2015/2016, 39.0% [95% CI, 28.7%-49.3%]; 86.9% increase; Nunavut: 2005, 46.0% [95% CI, 39.5%-52.9%]; 2015/2016, 62.4% [95% CI, 57.4%-67.4%]; 35.5% increase). Detailed information about health regions with the most rapid increase or decrease in age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of each cardiovascular risk factor is shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Socioeconomic Inequalities

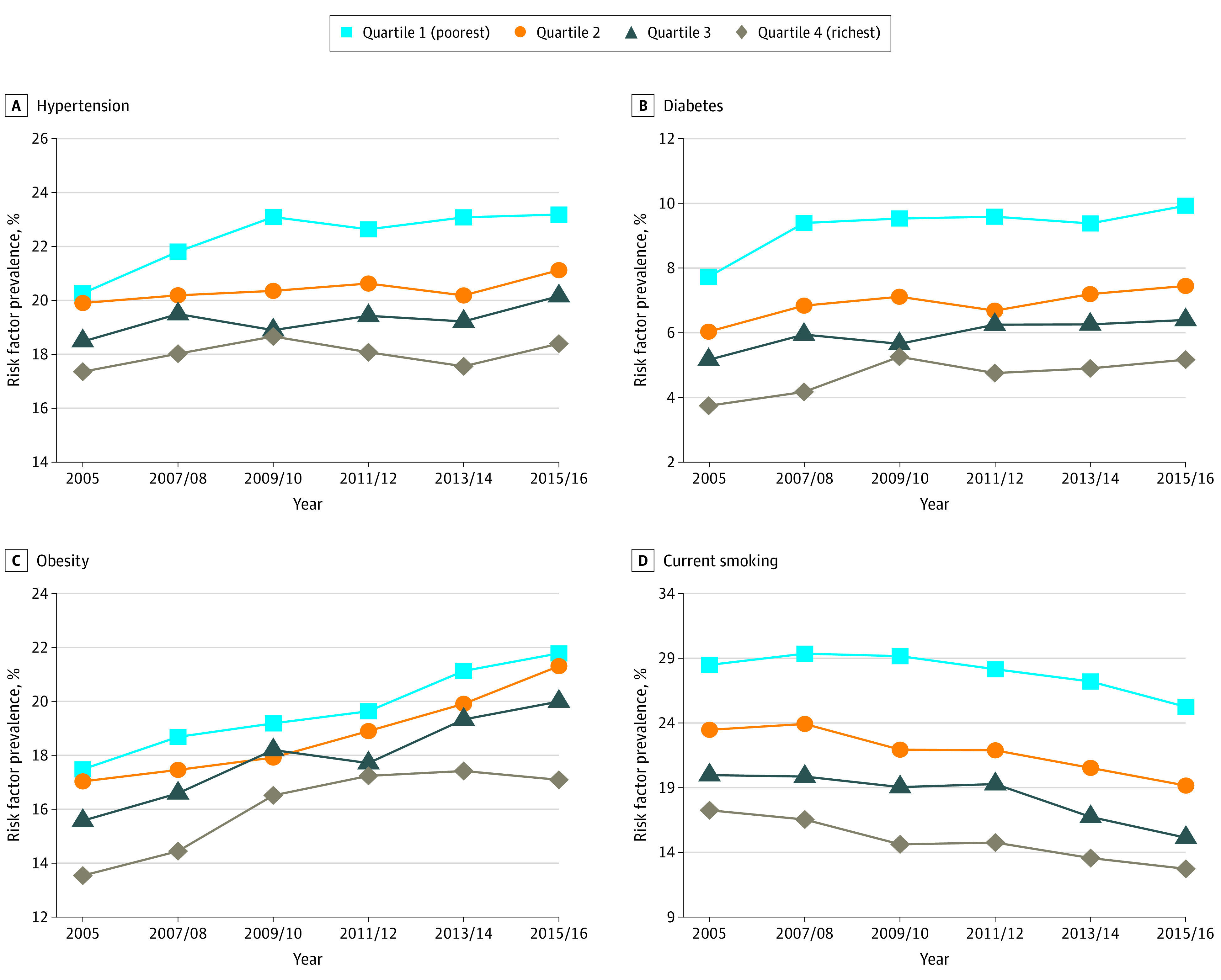

The distribution of age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of each cardiovascular risk factor across income quartiles overall and by sex is presented in Figure 2 and eFigure 5 in the Supplement. In addition to obesity among men, all cardiovascular risk factors tended to be more common among those with lower income (eg, prevalence of hypertension in both sexes, 2015/2016, quartile 1: 23.2% [95% CI, 22.4%-24.0%]; quartile 4: 18.4% [95% CI, 17.7%-19.1%]; prevalence of hypertension in men, 2015/2016, quartile 1: 24.0% [95% CI, 22.7%-25.4%]; quartile 4: 20.6% [95% CI, 19.6%-21.6%]; prevalence of hypertension in women, 2015/2016, quartile 1: 22.2% [95% CI, 21.2%-23.2%]; quartile 4: 16.2% [95% CI, 15.2%-17.1%]). The SII and RII presented in Table 3 suggested consistent absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities in hypertension, diabetes, and current smoking over time (eg, RII for hypertension in both sexes, 2005: 1.25 [95% CI, 1.18-1.33]; 2015/2016: 1.34 [95% CI, 1.26-1.43]). However, the phenomenon of absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities in obesity was only found among women (eg, RII for 2015/2016 for obesity in women; 1.74 [95% CI, 1.56-1.93]; men: 1.09 [95% CI, 0.99-1.21]). Trend analyses showed that there was a statistically significant increase in the SII and RII for hypertension and a statistically significant increase in the RII for current smoking (Table 3), suggesting the corresponding absolute and relative socioeconomic inequalities were widening between 2005 and 2016.

Figure 2. Overall Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Income Quartile.

Table 3. Changes in Absolute and Relative Socioeconomic Inequalities for Each Cardiovascular Risk Factor.

| Year | Predicted mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sexesa | Menb | Womenb | |||||||||

| SII | RII | SII | RII | SII | RII | ||||||

| Hypertension | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) | 1.25 (1.18 to 1.33) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.03)c | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.19)c | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.08) | 1.44 (1.31 to 1.57) | |||||

| 2007/2008 | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 1.28 (1.20 to 1.37) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04)c | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.22)c | 0.08 (0.06 to 0.09) | 1.50 (1.38 to 1.63) | |||||

| 2009/2010 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 1.37 (1.27 to 1.47) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.05) | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.11) | 1.59 (1.44 to 1.75) | |||||

| 2011/2012 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 1.36 (1.26 to 1.46) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.06) | 1.19 (1.07 to 1.33) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.11) | 1.55 (1.41 to 1.71) | |||||

| 2013/2014 | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.09) | 1.42 (1.32 to 1.53) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.07) | 1.22 (1.09 to 1.37) | 0.10 (0.08 to 0.12) | 1.69 (1.54 to 1.86) | |||||

| 2015/2016 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 1.34 (1.26 to 1.43) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.06) | 1.21 (1.10 to 1.32) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.10) | 1.52 (1.39 to 1.66) | |||||

| P for trend | .004 | .01 | .004 | .01 | .005 | .002 | |||||

| Direction of trend | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase | |||||

| Diabetes | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 2.60 (2.28 to 2.98) | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.06) | 2.11 (1.76 to 2.53) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 3.45 (2.84 to 4.20) | |||||

| 2007/2008 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 2.51 (2.19 to 2.88) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.07) | 2.24 (1.82 to 2.76) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 2.92 (2.41 to 3.53) | |||||

| 2009/2010 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 2.44 (2.11 to 2.81) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.07) | 2.06 (1.72 to 2.46) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 3.15 (2.53 to 3.91) | |||||

| 2011/2012 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 2.43 (2.08 to 2.84) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 2.26 (1.87 to 2.72) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 2.67 (2.10 to 3.40) | |||||

| 2013/2014 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 2.41 (2.11 to 2.76) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.07) | 1.95 (1.63 to 2.33) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.08) | 3.24 (2.71 to 3.88) | |||||

| 2015/2016 | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.08) | 2.46 (2.16 to 2.81) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.08) | 2.15 (1.83 to 2.54) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.09) | 2.95 (2.38 to 3.64) | |||||

| P for trend | .07 | .75 | .29 | .86 | .12 | .75 | |||||

| Direction of trend | None | None | None | None | None | None | |||||

| Obesity | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) | 1.37 (1.27 to 1.47) | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.02) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | 0.10 (0.08 to 0.12) | 1.95 (1.74 to 2.18) | |||||

| 2007/2008 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 1.43 (1.32 to 1.55) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 1.11 (0.99 to 1.25) | 0.10 (0.09 to 0.12) | 1.91 (1.72 to 2.13) | |||||

| 2009/2010 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.05) | 1.18 (1.08 to 1.29) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.01) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.04) | 0.07 (0.05 to 0.10) | 1.56 (1.38 to 1.77) | |||||

| 2011/2012 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) | 1.19 (1.10 to 1.30) | −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.00) | 0.89 (0.80 to 1.00) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.11) | 1.63 (1.44 to 1.84) | |||||

| 2013/2014 | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.06) | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.38) | 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.12) | 0.10 (0.08 to 0.12) | 1.69 (1.52 to 1.89) | |||||

| 2015/2016 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 1.35 (1.26 to 1.45) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.21) | 0.10 (0.08 to 0.12) | 1.74 (1.56 to 1.93) | |||||

| P for trend | .90 | .23 | .88 | >.99 | .94 | .06 | |||||

| Direction of trend | None | None | None | None | None | None | |||||

| Smoking | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 0.15 (0.14 to 0.17) | 1.95 (1.83 to 2.09) | 0.16 (0.13 to 0.18) | 1.85 (1.70 to 2.02) | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.17) | 2.09 (1.90 to 2.30) | |||||

| 2007/2008 | 0.18 (0.16 to 0.19) | 2.16 (2.01 to 2.32) | 0.20 (0.17 to 0.23) | 2.14 (1.95 to 2.35) | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.17) | 2.20 (1.99 to 2.42) | |||||

| 2009/2010 | 0.19 (0.17 to 0.21) | 2.44 (2.26 to 2.63) | 0.22 (0.19 to 0.25) | 2.42 (2.18 to 2.68) | 0.16 (0.14 to 0.18) | 2.47 (2.22 to 2.76) | |||||

| 2011/2012 | 0.18 (0.16 to 0.19) | 2.31 (2.13 to 2.49) | 0.19 (0.16 to 0.22) | 2.18 (1.95 to 2.43) | 0.16 (0.14 to 0.18) | 2.47 (2.21 to 2.77) | |||||

| 2013/2014 | 0.18 (0.16 to 0.20) | 2.52 (2.33 to 2.74) | 0.21 (0.18 to 0.23) | 2.43 (2.18 to 2.71) | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.18) | 2.66 (2.35 to 3.01) | |||||

| 2015/2016 | 0.17 (0.16 to 0.19) | 2.57 (2.37 to 2.79) | 0.18 (0.15 to 0.20) | 2.29 (2.06 to 2.56) | 0.17 (0.15 to 0.19) | 3.02 (2.67 to 3.41) | |||||

| P for trend | .43 | <.001 | .59 | .01 | .24 | <.001 | |||||

| Direction of trend | None | Increase | None | Increase | None | Increase | |||||

Abbreviations: SII, slope index of inequality; RII, relative index of inequality.

SII and RII are adjusted for age and sex.

SII and RII are only adjusted for age.

Discussion

The present study provides valuable evidence regarding the secular trends and geographic and socioeconomic patterns of major cardiovascular risk factors among Canadian adults between 2005 and 2016. Despite a favorable trend for current smoking, continuously increasing trends of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity were observed for both sexes. Geographically, great variability in the prevalence of these risk factors was found between health regions, although the patterns of change over time in most regions followed the national trends. In addition, persistent socioeconomic inequalities in hypertension, diabetes, and current smoking as well as obesity among women should warrant more attention.

Between 2005 and 2016, the overall tendency of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and current smoking in Canada continued the trends of the previous decade.6 Despite the remarkable achievements in the control of hypertension and diabetes,25 the prevalence of these 2 key risk factors is still increasing. These trends may be partly due to enhanced detection rates, but modern lifestyle changes, such as physical inactivity and processed food, also play a role. Encouragingly, we noted stable changes in hypertension and diabetes among young adults as compared with a previous study.6

Perhaps more worrisome is the high prevalence of obesity, which has increased at a much faster rate than that during 1994 to 2005.6 Given that obesity accounts for a significant amount of health care expenditure in Canada26 and can increase the risks of hypertension and diabetes,27 it is urgent to galvanize more effective actions on the prevention and management of obesity. Additionally, in line with global smoking trends,28 the smoking rate in Canada decreased from 22.1% to 17.8% during our study period. Nevertheless, several regions still experienced an increasing trend of smoking, such as Campbellton and Nunavut. Moreover, there is a considerable variation in the prevalence of smoking across health regions from 62.4% in Nunavut to 11.0% in the Richmond Health Service Delivery Area. In fact, our data also confirmed uneven distributions and complex trends of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity across health regions. These findings are particularly useful for policy makers to inform future resource allocation and design targeted interventions.

Similar to other developed countries,29,30,31,32,33 we found persistent socioeconomic inequalities in hypertension, diabetes, and smoking in Canada over the past decade. This may imply that current prevention policies have not improved the disparities between socioeconomic groups, and some researchers believe that they may even exacerbate the inequalities.34,35 Thus, future policies should not only target the entire population but also reduce social inequalities by paying more attention to socially disadvantaged groups. Interestingly, the absolute and relative socioeconomic inequality in obesity was only evident in women, which is consistent with results in other countries, such as Portugal and Scotland.36,37 This gender-specific pattern may be partly due to the fact that women with higher socioeconomic status are more aware of the negative health effects of obesity, while low-income men are more inclined to engage in manual labor.38,39 Therefore, it would be wise to pay more attention to women with low income when making obesity prevention strategies in Canada. Notably, identifying variations across health regions and socioeconomic groups is one step in examining the barriers to reducing major cardiovascular risk factors in Canadian population. Further study is required to elucidate which interventions can improve this situation.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, data for hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smoking were based on self-reports, which may lead to measurement errors and recall bias. Although measured indicators, such as measured blood pressure, were available in the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS), CHMS cannot provide health information at the health region level. Additionally, given the universal health care system in Canada, the prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension and diabetes was considered very low. Previous studies have suggested that the prevalence of hypertension in CCHS was quite close to that in other data sources, including CHMS.40 Second, we did not examine trends of other important risk factors, such as unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and dyslipidemia, due to lack of data or inconsistent definitions across survey cycles, although they are included in the definition of ideal cardiovascular health.41 Third, it is important to recognize that factors such as ethnicity, disability, immigration, and residency may also intersect with socioeconomic status to affect health equity, and thus, applying intersectional theory to understand health inequalities is an avenue for future research.42,43

Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the trends and distribution patterns of major cardiovascular risk factors among Canadian adults from 2005 to 2016. Encouraging trends were found: the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes no longer increased significantly among young people, and the prevalence of current smoking decreased among all Canadian adults. However, the continued increasing prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity is a cause for concern. Moreover, the distribution and trends of these risk factors varied widely across different health regions. Furthermore, socioeconomic inequalities in hypertension, diabetes, and current smoking, as well as obesity among women, persisted between 2005 and 2016 and even widened for hypertension and current smoking. Future interventions and policies targeted at reducing these cardiovascular risk factors in Canada should take into account the geographic and socioeconomic disparities.

eTable 1. Health Regions Combined to Ensure Historically Stable Units of Analysis

eTable 2. Neighboring Health Regions Combined Due to Small Populations

eTable 3. Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Age Group

eTable 4. Health Regions With Most Rapid Increase or Decline in Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors

eFigure 1. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Hypertension

eFigure 2. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Diabetes

eFigure 3. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Obesity

eFigure 4. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Current Smoking

eFigure 5. Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Income Quartile and Sex

References

- 1.Lang JJ, Alam S, Cahill LE, et al. Global Burden of Disease Study trends for Canada from 1990 to 2016. CMAJ. 2018;190(44):E1296-E1304. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarride JE, Lim M, DesMeules M, et al. A review of the cost of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(6):e195-e202. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70098-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):435-443. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roussel R, Steg PG, Mohammedi K, Marre M, Potier L. Prevention of cardiovascular disease through reduction of glycaemic exposure in type 2 diabetes: a perspective on glucose-lowering interventions. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(2):238-244. doi: 10.1111/dom.13033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K, Daviglus ML, Loria CM, et al. Healthy lifestyle through young adulthood and the presence of low cardiovascular disease risk profile in middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation. 2012;125(8):996-1004. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee DS, Chiu M, Manuel DG, et al. ; Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team . Trends in risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Canada: temporal, socio-demographic and geographic factors. CMAJ. 2009;181(3-4):E55-E66. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobe SW. Management of hypertension: regional variations in a greatly improved landscape. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26(8):415-416. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(10)70435-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP). BMJ. 2011;342:d442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touyz RM; Canadian Hypertension Education Program . Highlights and summary of the 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(7):565-571. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70278-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buajitti E, Frank J, Watson T, Kornas K, Rosella LC. Changing relative and absolute socioeconomic health inequalities in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study of adult premature mortality, 1992 to 2017. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shahidi FV, Parnia A, Siddiqi A. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in premature and avoidable mortality in Canada, 1991-2016. CMAJ. 2020;192(39):E1114-E1128. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Béland Y. Canadian community health survey—methodological overview. Health Rep. 2002;13(3):9-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padwal RS, Bienek A, McAlister FA, Campbell NR; Outcomes Research Task Force of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program . Epidemiology of hypertension in Canada: an update. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):687-694. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.07.734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society . 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25)(suppl 2):S102-S138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leventhal AM, Bello MS, Galstyan E, Higgins ST, Barrington-Trimis JL. Association of cumulative socioeconomic and health-related disadvantage with disparities in smoking prevalence in the United States, 2008 to 2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):777-785. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics Canada . Health regions and peer groups. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-402-x/2017001/hrpg-rsgh-eng.htm

- 17.Hajizadeh M, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Socioeconomic gradient in health in Canada: is the gap widening or narrowing? Health Policy. 2016;120(9):1040-1050. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajizadeh M, Bombay A, Asada Y. Socioeconomic inequalities in psychological distress and suicidal behaviours among Indigenous peoples living off-reserve in Canada. CMAJ. 2019;191(12):E325-E336. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.181374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, et al. 50-Year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386(9989):154-162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61774-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyoda N, Chikwe J, Itagaki S, Gelijns AC, Adams DH, Egorova NN. Trends in infective endocarditis in California and New York State, 1998-2013. JAMA. 2017;317(16):1652-1660. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinnon B, Harper S, Kaufman JS, Bergevin Y. Socioeconomic inequality in neonatal mortality in countries of low and middle income: a multicountry analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(3):e165-e173. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70008-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elgar FJ, Pförtner TK, Moor I, De Clercq B, Stevens GW, Currie C. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002-2010: a time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. Lancet. 2015;385(9982):2088-2095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61460-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arsenault C, Jordan K, Lee D, et al. Equity in antenatal care quality: an analysis of 91 national household surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):e1186-e1195. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30389-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonçalves H, Barros FC, Buffarini R, et al. ; Pelotas Cohorts Study Group . Infant nutrition and growth: trends and inequalities in four population-based birth cohorts in Pelotas, Brazil, 1982-2015. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(suppl 1):i80-i88. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alabousi M, Abdullah P, Alter DA, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor management performance in Canada and the United States: a systematic review. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(3):393-404. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran BX, Nair AV, Kuhle S, Ohinmaa A, Veugelers PJ. Cost analyses of obesity in Canada: scope, quality, and implications. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-11-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leenen FH, McInnis NH, Fodor G. Obesity and the prevalence and management of hypertension in Ontario, Canada. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(9):1000-1006. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1345-1422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YJ, Lee JS, Park J, et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in five major risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the Korean population: a cross-sectional study using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2014. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e014070. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Großschädl F, Stolz E, Mayerl H, Rásky É, Freidl W, Stronegger WJ. Prevalent long-term trends of hypertension in Austria: the impact of obesity and socio-demography. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tönnies T, Pohlabeln H, Eichler M, Zeeb H, Brand T. Relative and absolute socioeconomic inequality in smoking: time trends in Germany from 1995 to 2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;53:89-94.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Degerlund Maldi K, San Sebastian M, Gustafsson PE, Jonsson F. Widespread and widely widening? examining absolute socioeconomic health inequalities in northern Sweden across twelve health indicators. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1100-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandoval JL, Leão T, Cullati S, et al. Public smoking ban and socioeconomic inequalities in smoking prevalence and cessation: a cross-sectional population-based study in Geneva, Switzerland (1995-2014). Tob Control. 2018;27(6):663-669. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McPherson C, Ndumbe-Eyoh S, Betker C, Oickle D, Peroff-Johnston N. Swimming against the tide: a Canadian qualitative study examining the implementation of a province-wide public health initiative to address health equity. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0419-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson B, Huston P. Advancing health equity to improve health: the time is now. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2016;42(suppl 1):S11-S16. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v42is1a01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alves L, Stringhini S, Barros H, Azevedo A, Marques-Vidal P. Inequalities in obesity in Portugal: regional and gender differences. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(4):775-780. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu J, Coombs N, Stamatakis E. Temporal trends in socioeconomic inequalities in obesity prevalence among economically-active working-age adults in Scotland between 1995 and 2011: a population-based repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e006739. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ball K, Crawford D. Socioeconomic status and weight change in adults: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(9):1987-2010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:29-48. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atwood KM, Robitaille CJ, Reimer K, Dai S, Johansen HL, Smith MJ. Comparison of diagnosed, self-reported, and physically-measured hypertension in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(5):606-612. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. ; American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committee . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown TH, Richardson LJ, Hargrove TW, Thomas CS. Using multiple-hierarchy stratification and life course approaches to understand health inequalities: the intersecting consequences of race, gender, SES, and age. J Health Soc Behav. 2016;57(2):200-222. doi: 10.1177/0022146516645165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrams JA, Tabaac A, Jung S, Else-Quest NM. Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Soc Sci Med. 2020;258:113138. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Health Regions Combined to Ensure Historically Stable Units of Analysis

eTable 2. Neighboring Health Regions Combined Due to Small Populations

eTable 3. Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Age Group

eTable 4. Health Regions With Most Rapid Increase or Decline in Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors

eFigure 1. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Hypertension

eFigure 2. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Diabetes

eFigure 3. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Obesity

eFigure 4. Health Region–Level Age- and Sex-Adjusted Prevalence of Current Smoking

eFigure 5. Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Income Quartile and Sex