Abstract

Background:

We previously showed, in people starting treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), that stress is neither necessary nor sufficient for lapses to drug use to occur, despite an association between the two. Both theoretical clarity and case-by-case prediction accuracy may require initial differentiation among patients.

Aim:

To examine: (a) evidence for distinct overall trajectories of momentary stress during OUD treatment, (b) relationships between stress trajectory and treatment response, and (c) relationships between stress trajectory and momentary changes in stress and craving prior to lapses.

Methods:

We used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to collect ratings of stress and craving 3x/day for up to 16 weeks in 211 outpatients during agonist treatment for OUD. With growth mixture models, we identified trajectories of stress. We used mixed effect models to examine trajectory-group differences in the dynamics of stress and craving just before lapses to any drug use.

Results:

We identified four trajectories of stress: Increasing (13.7%); Moderate and Stable (23.7%); Declining and Increasing (18%); and Low (44.6%). Overall drug use and opioid craving were lowest in the Low Stress group. Overall drug use was highest in the Moderate and Stable group. Alcohol use and opioid craving were highest in the Increasing Stress group. Opioid craving increased before lapse for most groups, but stress increased before lapses for only the Moderate and Stable group.

Conclusion:

There are natural groupings of participants with distinct patterns of stress severity during OUD treatment. Momentary stress/craving/lapse associations may be better characterized when these groupings are considered first.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, stress, ecological momentary assessment, growth mixture models, individual differences, cluster analysis

1.0. Introduction

It is often taken as a truism that stress plays a primary role in lapse to drug use during treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs) such as opioid use disorder (OUD). Indeed, converging evidence from preclinical and human-laboratory manipulations have shown that stressful experiences can increase opioid self-administration (Shaham et al., 1992), increase the quantity of drugs (including opioids) consumed (Shaham, 1993; Thomas et al., 2011), and reinstate opioid-seeking behavior after cessation (Shaham et al., 1997; Ahmed et al., 2000).

Even so, stress has not emerged as a reliable predictor of lapse1 among humans within the timespan of a few minutes or hours; that is, momentary stress is not the only factor that precipitates lapse, nor does it precede every lapse (Furnari et al., 2015). Over the past two decades, our research group has examined proximal changes in self-reported stress and other background states (e.g., craving) in the moments preceding episodes of drug use during outpatient methadone or buprenorphine treatment for OUD, using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) (Burgess-Hull and Epstein, 2021). This work has revealed two primary findings on stress and lapse. First, the association between self-reported stress and lapse appears to depend on the time frame of assessment. We have documented higher momentary levels of self-reported stress in the days preceding a lapse to opioid use (Furnari et al., 2015), but we have never observed an orderly increase (or decrease) in momentary stress levels in the hours or minutes preceding use (Epstein et al., 2009; Preston et al., 2018). Second, even at the daily time frame, the stress/lapse association holds more clearly for some people than others (Furnari et al., 2015). This heterogeneity also applies to how often stressful events are experienced: our participants display stable but distinct trait-like differences in overall prevalence of stress during their time in treatment, and these between-person differences affect our ability to detect discrete moments of self-reported stress on a time course of hours with personalized machine-learning models (Epstein et al., 2020).

In the analyses presented here, we sought to identify meaningful groupings of participants with respect to the patterns of stress they experience during treatment for OUD. Specifically, we followed up on our finding of between-person differences in longitudinal patterns of self-reported stress (Epstein et al., 2020) in four ways. First, to better capture the dynamics of stress, we adopted a more granular time scale. Our prior focus had been on weekly prevalence (presence or absence) of discrete stress events (tallies of participant-initiated real-time reports); here we also incorporated daily mean levels of stress intensity, assessed at randomly prompted times. Second, we tested how our stress-trajectory groups differed on intra-treatment variables such as craving, exposure to drug cues, and continued drug use. Third, we examined how these groups differed on baseline screening variables such as demographics and drug-use history. Fourth, we examined whether the groups differed in momentary changes in stress or craving prior to lapse. Our broad goal was to determine whether evidence for associations between stress and lapse could be strengthened by looking within groups of people who were comparatively homogeneous in their longitudinal patterns of stress.

2.0. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N = 237) were opioid-dependent polydrug users seeking treatment for OUD at our treatment-research clinic in Baltimore, MD (National Clinical Trial Identifier NTC00787423). Inclusion criteria for enrollment were: age 18 – 75, physical dependence on opioids, and (because we were studying behavioral geography in a project not reported here) living or spending time in Baltimore city or a surrounding county. Exclusion criteria were: history of bipolar or any DSM-IV psychotic disorder; current DSM-IV alcohol or sedative-hypnotic dependence; cognitive impairment precluding informed consent or self-report; and medical conditions that could compromise study participation. During pre-enrollment screening, participants received physical and psychosocial assessments and completed the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1985).

The IRB of the National Institute on Drug Abuse approved the study. Participants gave written informed consent and all data were covered by a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

2.2. Study Procedures

Methadone or buprenorphine maintenance began at enrollment and continued for up to 18 weeks under one of two study arms: (a) a methadone or buprenorphine arm (n = 192) where participants attended clinic 5 – 7 days a week and provided urine samples three times weekly, or (b) an “office-based” buprenorphine arm (n = 45) where participants attended clinic two days a week and provided urine samples twice weekly. Urine was collected under observation and screened for illicit drugs (heroin and other opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, PCP, benzodiazepines, and cannabinoids). Medication type was determined by the study physician’s judgment and by participant preference. Dosage was individually tailored.

2.2.1. EMA Data Collection

A smartphone was provided to each participant after two weeks of treatment. Smartphones prompted participants to complete EMA items at three random times during the participant’s normal waking hours. For each randomly prompted entry, participants reported their current stress, opioid craving, and cocaine craving (Likert scale: 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “extremely”), who they were with, and whether they had been offered, seen, or seen others using opioids, cocaine, cannabis, methamphetamine, tobacco, or alcohol since they arrived at their present location (or, if they were walking, during the last 5 minutes). Participants were also asked to initiate event-contingent (EC) EMA entries whenever they used drugs (EC drug events) and whenever they felt “more stressed, overwhelmed, or anxious than usual” (EC stress events; 1 = “not bad at all” to 10 = “the worst you’ve ever felt”). The exact instructions on the day the smartphone was issued were:

…we want you to report when you are feeling stressed. What you should do is make an entry anytime you feel more stressed, anxious, overwhelmed than you usually do. It might be about something small, like being about to leave home and realizing you have to find your keys first. Or it might be something bigger, like having an argument with someone you care about. Or it might be something a lot bigger than that. It might also be that you just suddenly started to feel stressed, anxious, or overwhelmed even though nothing specific happened. You can fill in the details when you make the entry.

During EC entries, participants reported whether they were alone or with others, whether they had seen others using drugs, and their current level of opioid craving. In an end-of-day entry every evening, participants could report instances of stress or drug use that they had missed reporting that day.

Smartphones were carried by participants for up to 16 weeks. Participants were paid $10–30 each week for completing at least 23 of their 28 possible random prompts. If participants did not meet completion criteria for two consecutive weeks after an initial warning, they were discharged and assisted with transfer to a community-based addiction treatment. To help ensure accurate drug-use reporting (without incentivizing drug use), participants received $5 for each negative urine screen with no EMA-reported drug use, and $3 each time they had a positive urine screen with a matching EMA entry.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

To create a variable reflecting stress during the study, we re-coded the EC stress reports to the same scale as the random-prompt stress reports (a score of 1–2 was recoded to 1; 3–4 to 2; 5–6 to 3; etc.). We then averaged the random-prompt and EC stress responses within each day to get one stress score per day. We then selected participants (n = 211) who completed at least 40% of the study (48 days) and removed participant days that were missing all stress values (189 out of 20289 days [0.9%]). Using the lcmm package (Proust-Lima et al., 2017) in R (R Core Team, 2020), we fit growth-mixture models (GMM) to the daily stress scores to identify longitudinal trajectories of stress.

We compared the relative fit of increasingly complex models of linear and nonlinear growth (e.g., polynomials, I-splines) for models with 1 to 7 trajectory groups. We also examined variability in growth within and across trajectory groups by fitting models with random intercepts and/or slopes. The dependent variable for all models was average daily stress. The independent variables were day-in-treatment and indicator variables for dropout category (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics: Pre-treatment and EMA Variables (n = 211)

| Pre-treatment Variables | Intra Treatment Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | n (%) | Variable | Mean (SD) |

| Demographics | Medication | |||

| Age | 43.35 (9.57) | Methadone – n (%) | 99 (47) | |

| Male | 164 (78) | Time in Study | ||

| Non-white | 144 (69) | Days in Study | 96.98 (23.14) | |

| Employed | 153 (73) | Drug use During Study | ||

| Drug use history | Any Drug Use | 0.27 (0.22) | ||

| Alcohol use (past 30 days) | 4.84 (7.47) | Heroin Use | 0.14 (0.17) | |

| Heroin use (past 30 days) | 19.75 (11.75) | Other Opioid Use | 0.02 (0.04) | |

| Other opioid use (past 30 days) | 7.83 (10.40) | Any Opioid Use | 0.15 (0.17) | |

| Cocaine use (past 30 days) | 4.18 (8.10) | Cocaine Use | 0.11 (0.16) | |

| Cannabis use (past 30 days) | 3.27 (7.80) | Cannabis Use | 0.07 (0.17) | |

| Polysubstance use (past 30 days) | 10.07 (10.51) | Alcohol Use | 0.05 (0.10) | |

| Longest period of abstinence (months) | 12.74 (25.49) | Cue-Exposure & Stress | ||

| Time since most recent abstinence (months) | 27.73 (43.41) | Drug Cue Exposure | 0.89 (0.87) | |

| Money on drugs (past 30 days) | 994.46 (1198.97) | Stress Events | 0.13 (0.23) | |

| Legal problems | Drug use with others | 0.10 (0.12) | ||

| Arrested and charged (lifetime) | 7.56 (11.40) | |||

| Months incarcerated (lifetime) | 38.04 (56.32) | Completion and Dropout Numbers | ||

| Illegal Activities for $ (past 30 d) | 4.69 (9.60) | Dropout Category | n (%) | |

| Physical, Psych., & Social Health | Completed | 147 (70) | ||

| Medical Problems (past 30 days) | 1.07 (4.80) | Dropout: Incarcerated | 5 (2) | |

| Bothered by psychological problems (past 30 days) | 0.21 (0.76) | Dropout: Medical discharge | 2 (1) | |

| Mental health problems (lifetime) | 0.59 (0.98) | Dropout: Transferred to another clinic | 15 (7) | |

| Number of close friends | 2.67 (2.78) | Dropout: Non-compliant EMA | 8 (4) | |

| Serious conflict with family (past 30 days) | 0.93 (4.05) | Dropout: Other | 34 (16) | |

Note. “Dropout: Non-compliant EMA” includes participants who were non-compliant with the pre-specified EMA procedures. “Dropout: Other” includes participants who got a job, were expelled due to diversion, moved to another state or region outside of study boundaries, or experienced some other life event that disrupted their ability to participate in the study.

To select a final model, we compared the relative fits of the estimated models with the AIC and BIC (lower values indicate better relative fit), posterior probabilities of trajectory membership (PPM), size of the estimated trajectory groups, differences between observed and model-predicted stress values, and substantive interpretability/importance of the trajectory groups. More information on GMM, and specific details on model fitting and model selection for these analyses is in the Supplemental Material. Also see Ram and Grimm (2009) and Burgess-Hull (2020).

2.3.1. Post-hoc comparisons of trajectory groups

Participants were assigned to the trajectory group corresponding to their highest PPM.2 We then used pairwise chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests to compare groups on pretreatment measures. Pairwise comparisons were adjusted for the false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995), and rank-biserial correlations were calculated for effect sizes.

2.3.2. Group differences in EMA measures collected during treatment

We examined intra-treatment drug use, drug-cue exposure, and stress events, with all measures based on the number of times that any EMA entry (randomly prompted, event-contingent, or end-of-day) contained an event report. Drug use reflected nonmedical use of any psychoactive drug, not just opioids, a decision we made to increase the prevalence of use reports and because such use might be considered a lapse during the first few weeks of treatment. We coded drug use three ways: (a) nonprescribed use of a drug (alcohol, heroin, other opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine, cannabis, benzodiazepines, diverted methadone/buprenorphine, other nonprescribed drugs), (b) drug use by category (heroin, non-heroin opioids, any opioid, cannabis, and alcohol), and (c) drug use in the presence of another person. An average number of drug-use reports per day was calculated by dividing the sum of each measure by the total days a participant was in the study. Drug-cue exposure was calculated as the average daily frequency a participant reported seeing any drugs, being offered any drugs, or seeing someone selling/using drugs nearby. Stress events was calculated as the average number of event-contingent stress reports per day.

2.4. Multilevel models

To examine whether changes in stress and craving before a lapse event differed across stress-trajectory groups, we fit separate multilevel models to EMA data from participants in each of the stress trajectories with the nlme package (Pinheiro et al., 2019) in R. Stress, opioid craving, and cocaine craving were the main dependent variables, and hours before an EC drug-use report was the main predictor. Because previous studies examining proximal changes in momentary states in the hours before drug use have used a variety of different intra-day timeframes (e.g., Epstein et al., 2009; Preston et al., 2018; Shiffman and Waters, 2004), instead of selecting the number of hours of stress and craving reports to include in our models a priori, we tested models with 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, or 10 hours of stress/craving reports before lapse. This allowed us to examine how our estimates differed/changed across different time frames.

All multilevel models controlled for sex, age (centered), and ethnicity. We used a random intercept and a first-order autoregressive error structure. We tested for nonlinear changes before drug use with linear and quadratic terms for hours before use.

3.0. Results

3.1. Sample

Table 1 shows pretreatment demographics, drug use, legal/criminal problems, and health characteristics, along with dropout/completion rates and EMA-variable summaries. Most participants were male (78%), non-white (69%), and employed at least part-time (73%). Mean age was 43.4 (SD=9.6). The distribution of treatment medication was well-balanced, with only slightly more patients receiving buprenorphine (53%) than methadone (47%). Most participants completed the study (70%; mean days in study was 96.9 days—note that we had already excluded participants who had provided < 48 days of EMA data).

3.2. Identification of Stress Trajectories

GMMs with quadratic I-splines (3-equidistant knots) and fixed effects fit substantially better than linear/polynomial GMMs, and GMMs with random effects.

Although the 5-Trajectory GMM had the lowest AIC and BIC values, its model-predicted stress values matched poorly with observed values. The 3-Trajectory GMM had high PPM, but worse (higher) AIC and BIC values than the 4-Trajectory model. Furthermore, the 3-Trajectory model combined two seemingly important groups into a single group. The 4-Trajectory model had the second-lowest AIC and BIC values, high PPM, and high-concordance between model-predicted values and observed values. Therefore, we selected the 4-Trajectory Quadratic I-spline GMM as the final model. More details about model selection, including model-fit statistics for the 1 – 6 trajectory I-spline GMMs, are in the online Supplement.

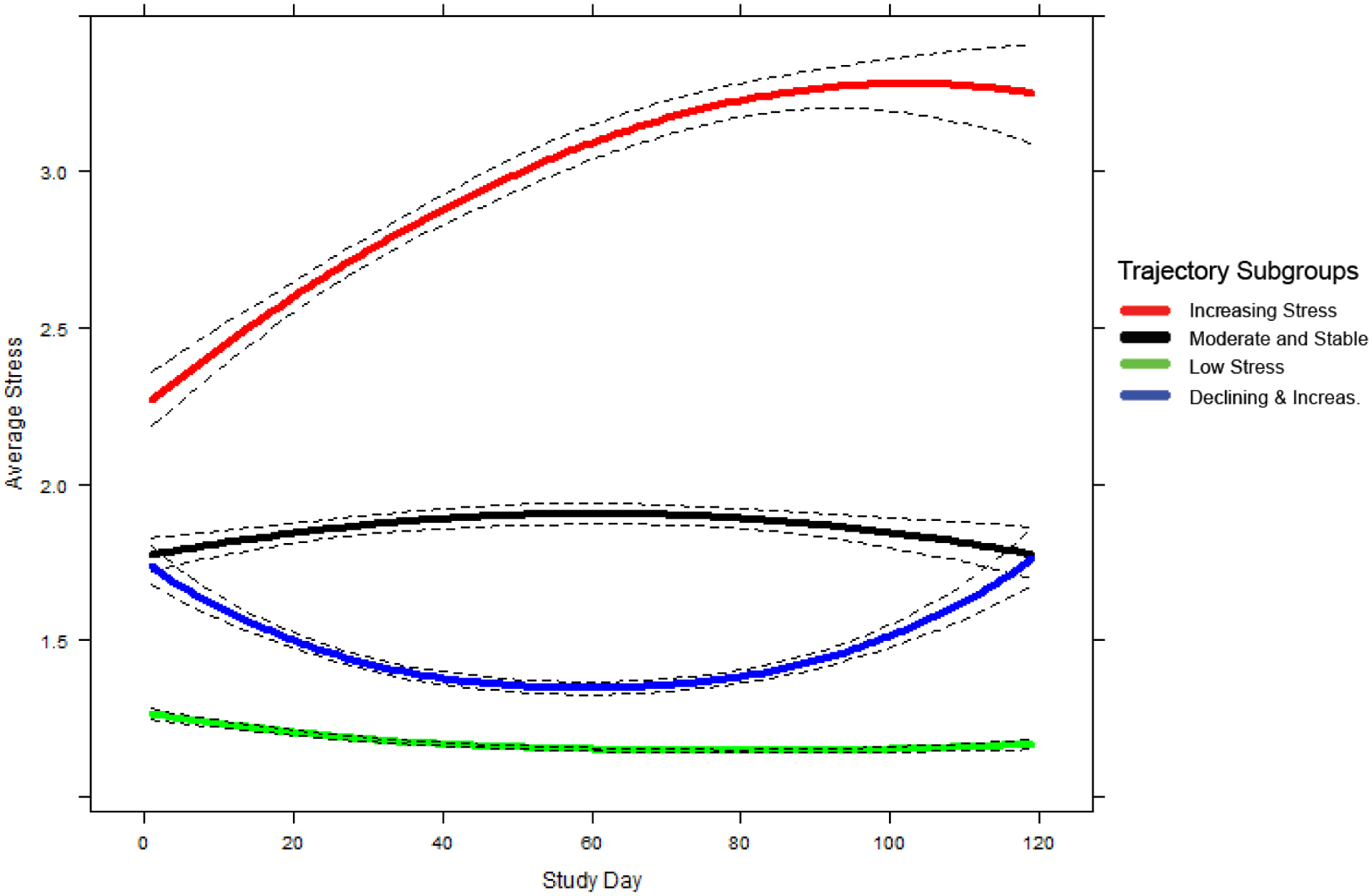

3.3. Description of 4-Trajectory Stress Growth-Mixture Model

Figure 1 shows the average daily stress ratings for the four-trajectory model. Table 2 shows the size of each group and the average PPM. The first trajectory group (n = 29; 13.7% of sample) was characterized by high initial levels of stress that continued to increase over the course of treatment; we named it the Increasing Stress trajectory. The second group (n = 50; 23.7%) was characterized by initially moderate levels of stress that remained stable during treatment; we named it the Moderate and Stable trajectory. The third group (n = 94; 44.6%) was characterized by consistently low levels of stress during treatment; we named it the Low Stress trajectory. The fourth group (n = 38; 18%) was characterized by moderate levels of stress at the beginning of treatment, which slightly decreased until the middle of treatment, then increased near the end; we named it the Declining and Increasing trajectory.

Figure 1.

Mean trajectories (solid lines) and 95% pointwise CI’s (dashed lines) for self-reported stress by day in study. Average stress for each trajectory subgroup was predicted by a 4-Trajectory I-spline (3-equidistant-knots) growth mixture model with a quadratic slope.

Table 2.

Size, Posterior Probability of Membership, Demographic, Treatment Characteristics, Health, Mental Health, Legal/Employment Issues, and Social Support of Stress Trajectory Subgroups

| Increasing Stress (cluster 1) | Moderate and Stable (cluster 2) | Low Stress (cluster 3) | Declining and Increasing (cluster 4) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size and Classification Accuracy | |||||

| N (% of sample) | 29 (13.7%) | 50 (23.7%) | 94 (44.6%) | 38 (18.0%) | - |

| Average Posterior Probability of Membership | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | - |

| Demographics, Treatment, and Days in Study | |||||

| Age (mean) | 41.09 | 44.25 | 43.73 | 42.93 | 0.487 |

| Male (%) | 72 | 80 | 78 | 79 | 0.884 |

| White (%) | 45 | 38 | 25 | 26 | 0.129 |

| Married (%) | 21 | 16 | 13 | 16 | 0.779 |

| Unemployed (%) | 24 | 22 | 31 | 26 | 0.719 |

| Methadone (%) | 41 | 50 | 47 | 47 | 0.907 |

| Days in Study (mean) | 94.24 | 93.10 | 101.20 | 93.74 | 0.205 |

| Health | |||||

| Medical Problems (Past 30 days) | 1.66 | 0.29 | 1.54 | 0.18 | 0.964 |

| Mental Health | |||||

| Perceived Stress Scale (total)* | 24.40 | 24.76 | 23.30 | 22.50 | 0.445 |

| Mental Health Problems (past 30 days) | 1.90 | 1.24b | 0.20ab | 1.24 | 0.091 |

| Mental Health Problems (lifetime) | 0.72A | 0.90B | 0.36AB | 0.53 | 0.021 |

| # times treated for psychological problems – Hospital | 0.14A | 0.12B | 0.01AB | 0.08 | 0.043 |

| # times treated for psychological problems – Outpatient | 0.34 | 0.52A | 0.14A | 0.26 | 0.038 |

| Bothered by psychological problems past 30 days | 0.41a | 0.26b | 0.05ab | 0.13 | 0.071 |

| Family history of psychiatric problems | 0.59a | 0.24 | 0.10a | 0.26 | 0.086 |

| Legal Problems | |||||

| Times arrested and charged (lifetime) | 4.24ab | 6.20a | 10.28bc | 5.18c | 0.035 |

| # of Disorderly Conduct and Driving Violations (lifetime) | 0.93 | 1.06A | 0.45A | 0.55 | 0.029 |

| Legal convictions (lifetime number) | 2.24 | 2.52 | 4.58 | 2.87 | 0.126 |

| Months incarcerated (lifetime months) | 34.79 | 33.34 | 45.15 | 30.45 | 0.141 |

| Length of last incarceration (months) | 14.38ab | 13.30a | 17.34b | 13.03 | 0.123 |

| Social Support & Relationships | |||||

| Number of close friends | 2.62 | 2.74 | 2.98 | 2.05 | 0.497 |

| Serious conflict with family | 0.52 | 1.94a | 0.31a | 0.58 | 0.085 |

Note. Data were collected from the Addiction Severity Index structured interview. Bolded uppercase superscripts with the same letter denote trajectory subgroups that differ from one another at p < 0.05. Lowercase non-bolded superscripts with the same letter denote trajectory subgroups that differ from one another at p < 0.10.

n = 154.

3.4. Pretreatment differences between stress-trajectory groups

Table 2 and Supplemental Table 2 show summary data for pretreatment measures for each group. In addition to the pairwise comparisons in these tables, we also tested how each stress group differed from the rest of the sample; the latter findings are summarized below.

The groups did not differ on demographic measures such as sex, race/ethnicity, or employment, nor by the type of opioid-agonist medication administered (methadone vs. buprenorphine). Groups also did not differ for days retained in treatment.

For drug-use history at treatment entry, the Increasing Stress group reported the highest lifetime (Wilcoxon W = 2009, p = .023, rg = −0.23) and past-30-day (W = 2037, p = .045, rg = −0.23) use of non-heroin opioids compared to all other trajectory groups. Conversely, the Low Stress trajectory reported the lowest lifetime use of non-heroin opioids (W = 6460, p = .009, rg = 0.18). The trajectory groups did not differ on other aspects of drug-use history.

On the psychiatric-functioning section of the ASI, the Low Stress group reported the lowest levels of problems, both over their lifetime (W = 6462, p = .009, rg = 0.18) and in the past 30 days (W = 5947, p = .019, rg = 0.08), and were less likely to report having been bothered by psychiatric problems during the past 30 days (W = 5901, p = .029, rg = 0.07). The Low Stress group also reported the fewest number of lifetime treatments for psychiatric problems, both inpatient (W = 5865, p = .024, rg = 0.07) and outpatient (W = 6368, p = .005, rg = 0.16). In contrast, the Moderate and Stable trajectory reported the highest levels of lifetime psychiatric problems (W = 3359, p = .034, rg = 0.17), and the highest number of inpatient (W = 3751, p = .048, rg = −0.07) and outpatient psychiatric treatment episodes (W = 3494, p = .045, rg = −0.13). The Increasing Stress group was the most likely to report a family history of psychiatric problems (W = 2202, p = .017, rg = −0.17).

Group differences on the legal-status section of the ASI are described in the Supplement.

3.4.1. Differences between stress-trajectory groups during treatment

Table 3 shows trajectory-group differences in EMA-derived measures of drug use, cue exposure, stress, and craving during treatment. Overall drug use (W = 6962, p = < .001, rg = 0.27), cannabis use (W = 6467, p = .018, rg = 0.18), and alcohol use (W = 6402, p = .032, rg = 0.16) was lowest in the Low Stress group. Overall drug use (W = 3221, p = .033, rg = −0.20) and opioid use (W = 3252, p = .040, rg = −0.19) was highest in the Moderate and Stable group. Alcohol use was highest in the Increasing Stress group (W = 2013, p = .031, rg = −0.24).

Table 3.

Drug use, Cue Exposure, Stress, and Social Contact During Treatment by Stress Trajectory Subgroups

| Increasing Stress (cluster 1) | Moderate and Stable (cluster 2) | Low Stress (cluster 3) | Declining and Increasing (cluster 4) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Drug Use During Study (average daily rate) | 0.30a | 0.32B | 0.21aBc | 0.30c | 0.010 |

| Heroin Use (average daily rate) | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.158 |

| Other Opiate Use (average daily rate) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.989 |

| Any Opiate Use (average daily rate) | 0.13 | 0.19a | 0.12a | 0.15 | 0.122 |

| Cocaine Use (average daily rate) | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.603 |

| Cannabis Use (average daily rate) | 0.10a | 0.08 | 0.04a | 0.08 | 0.096 |

| Alcohol Use (average daily rate) | 0.07A | 0.06 | 0.03A | 0.06 | 0.035 |

| Drug Cues (average daily rate) | 1.04 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.173 |

| Drug use with others (average daily rate) | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.236 |

| Stress Events□ (average daily rate) | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.08a | 0.11a | 0.069 |

| Opioid Craving (average response) | 4.60AB | 4.22CD | 3.02AC | 3.30BD | < .001 |

| Cocaine Craving (average response) | 3.41 | 3.40 | 2.95 | 3.11 | 0.329 |

Note. Data were collected during EMA assessments. Bolded uppercase superscripts with the same letter denote trajectory subgroups that differ from one another at p < 0.05. Lowercase non-bolded superscripts with the same letter denote trajectory subgroups that differ from one another at p < 0.10.

= event-contingent stress report.

Opioid craving was lowest in the Low Stress group (W = 7258, p = < .001, rg = 0.32) and highest in the Increasing Stress group (W = 1652, p = .001, rg = −0.37).

3.5. Results from multilevel models examining changes in stress and craving before drug use

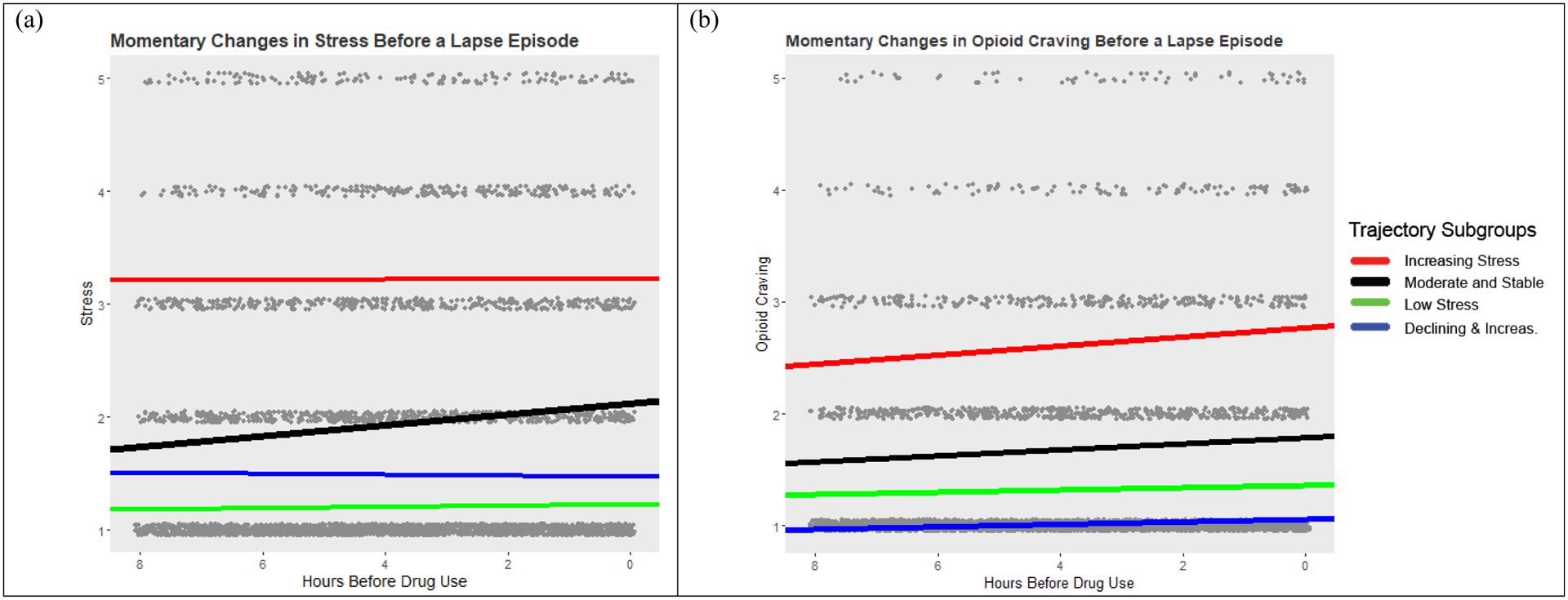

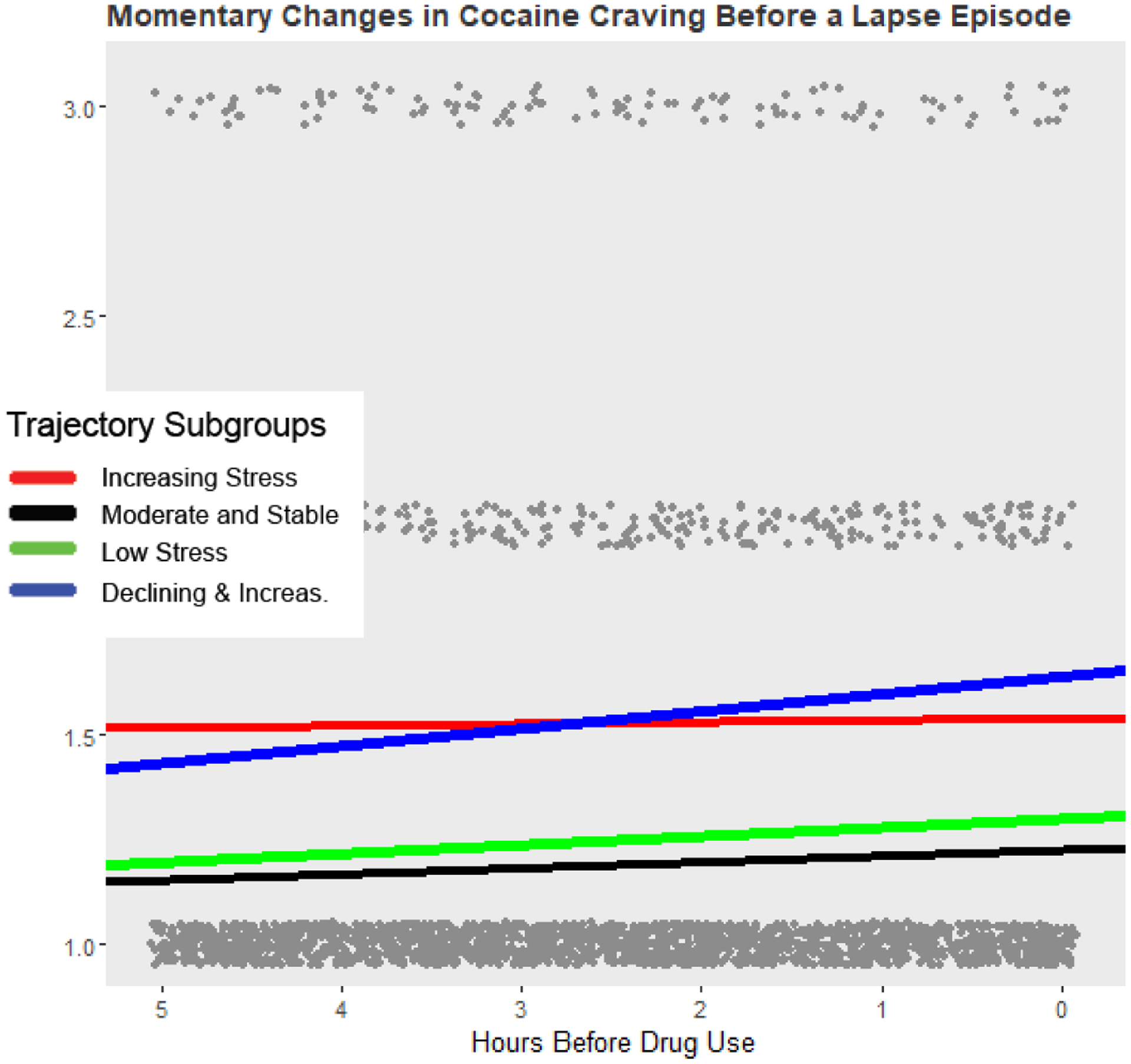

Figures 2 and 3 show model-predicted and observed EMA ratings of stress and craving before drug use for each of the stress-trajectory groups, for the 8- or 5-hour models. Supplemental Tables 3 – 5 show parameter estimates and effect sizes for the models fit for each group.

Figure 2.

EMA ratings of stress and opioid craving (grey dots) in the 8-hours prior to a drug use report. Solid lines are the model predicted estimates of stress (panel a) and opioid craving (panel b) from multilevel models fit to each individual subgroup.

Figure 3.

EMA ratings of cocaine craving (grey dots) in the 5-hours prior to a drug use report. Solid lines are the model predicted estimates of cocaine craving from multilevel models fit to each individual subgroup. The y-axis has been reduced to emphasize changes in craving before drug use.

For all models fit with < 7hrs of ratings of stress, there were no significant changes in stress before drug use for any of the stress-trajectory groups. With >7 hrs of stress data, there was a significant linear increase in stress in the hours before drug use for the Moderate and Stable group. The effect size for the linear slope estimate was largest in the Moderate and Stable group regardless of the timeframe examined. For the other groups, changes in stress before drug use never reached statistical significance.

Momentary changes in opioid craving before drug use were most obvious for models fit to > 6 hours of opioid craving data. All stress-trajectory groups, except the Declining and Increasing group, showed reliable increases in opioid craving in the hours before drug use (increases were only reliable for the Declining and Increasing group when models used 9 or 10 hours of data). The strongest effects were observed for participants in the Increasing Stress group, followed by the Moderate and Stable, Declining and Increasing, and Low Stress groups.

The most obvious changes in cocaine craving were observed for models fit to < 7 hours of craving data. For both the 5- and 6-hour timeframes, the Low Stress and Declining and Increasing trajectories were the only groups that showed increases in cocaine craving before drug use. The effect was largest for the Declining and Increasing group.

4.0. Discussion

We identified day-to-day changes in average momentary stress levels among adults in their first 16 weeks of methadone or buprenorphine maintenance for OUD. Our stress data were more complete than in our first large EMA study with this population (Epstein et al., 2009; Preston and Epstein, 2011) because here we asked participants to initiate a report for each acute incident of stress rather than giving stress ratings only when randomly prompted. In our prior analyses from this data set (Furnari et al., 2015), we had not yet integrated event-contingent reports of stress with the random-prompt ratings, as we did here. Using this more integrated measure of acute and background stress, we identified four groupings of participants with distinctive trajectories. We also showed that these groupings were at least modestly associated with differences at treatment entry and during treatment.

4.1. Pre-treatment characteristics and treatment retention across stress-trajectory groups

We found no reliable differences among the stress-trajectory groups in terms of sex, race/ethnicity, or employment status. Surprisingly, we also found few differences in drug-use history, with the exception of use of non-heroin opioids. Here, the Increasing Stress group had used non-heroin opioids for more years, and for more of the 30 days prior to enrollment, compared to other groups. The opposite was found for lifetime use of non-heroin opioids in the Low Stress group.

The stress-trajectory groups also differed in baseline measures of psychiatric problems and psychiatric-treatment history. The Low Stress group reported the lowest levels of lifetime psychiatric problems and were least likely to report being bothered by these problems during the same 30 days, which may be unsurprising given that stress accompanies many psychiatric problems. The Low Stress group also reported the fewest number of inpatient/outpatient treatment episodes for psychiatric problems, perhaps indicating greater lifetime psychiatric stability relative to the other groups. Unexpectedly, it was the Moderate and Stable group that had the highest levels of lifetime psychiatric problems, and the highest numbers of inpatient/outpatient psychiatric treatments. We speculate that this group’s greater prior exposure to psychiatric treatment may have increased its ability to prevent or cope with stress (e.g., Smith and Glass, 1977; Hall et al., 1994; Roberts et al., 2016).

Length of retention in clinic did not differ significantly by stress-trajectory groups. This conflicts with our prior finding (in an overlapping sample) that frequent momentary stress predicts dropout (Panlilio et al., 2019). However, our prior analysis included patients who dropped out at any time, while our current classifications of stress—requiring more complete data—included only patients with at least 48 days of EMA.

4.2. Craving and drug use during treatment across stress-trajectory groups

The clinical significance of the stress-trajectory classifications is underscored by the group differences we found in day-to-day momentary states and behaviors during treatment. The Low Stress group reported the lowest levels of opioid craving and any drug use during treatment, whereas the Moderate and Stable group reported the highest levels of any use. The Increasing Stress group reported the highest levels of opioid craving during treatment, and the highest rates of alcohol use (despite not having entered treatment with higher rates of alcohol use). This may have been a response to, and/or a contributor to their stress.

4.3. Stress and craving before moments of drug use across stress trajectory groups

Using 7 to 10 hours of EMA data, we found a significant linear increase in stress before drug use in only one group: the Moderate and Stable group (which also had the highest overall drug use during treatment). We do not know why this specific pattern of results occurred, but it does support our general expectation that momentary stress/drug relationships would differ by stress trajectory.

The linear increases in opioid and cocaine craving are consistent with prior findings from our group (Epstein et al., 2009; Preston et al., 2018; Panlilio et al., 2021) and others (Serre et al., 2018). However, the differential effects observed across the trajectory groups for changes in cocaine craving before drug use is surprising and warrants further attention. The patterns of statistical significance across the different timeframes examined likely reflects increased precision with more datapoints. These patterns may also reflect complex curvilinear (beyond quadratic) changes over time; researchers should keep this in mind when modeling changes in momentary states over time.

4.4. Interpretability of the stress trajectories

Decreases in stress during treatment stabilization seem unsurprising; other studies have shown that indices of psychological status (such as depression scores) reliably improve during agonist treatment for OUD (Mohammadi et al., 2020). Increases and curvilinear patterns require more explanation. One possibility is that stress sometimes accompanied successful avoidance of lapses to drug use—either because temptation toward lapse were inherently stressful or because the absence of intoxication permitted fuller expression of stress from other sources. This might partly explain findings that the Increasing Stress group reported the highest levels of opioid craving (but not opioid use) during treatment.

These findings are not without limitations. The EMA data were collected from a non-random sample of participants seeking treatment for OUD in Baltimore, MD In addition to a history of heroin and other opioid use, these participants also had a history of polysubstance and alcohol use. GMM results can also be sensitive to sample characteristics and distributional assumptions. Replication is necessary to determine if these models generalize to non-urban OUD samples or samples with different drug-use histories. The length of EMA data collection may have also led to participant fatigue. However, examination of the data over time did not reveal evidence for reduced variability or an increase in careless responding.

4.5. Conclusions

We found natural groupings of participants who displayed longitudinal trait-like patterns of stress severity and differed in their momentary stress/drug associations. Although we cannot say definitively why the trajectories were shaped as they were, the information obtained here can still be useful. Clinicians might use these groupings as a tool to tailor treatment—if a patient’s trajectory can be identified early enough. In a parallel set of analyses (under review), we have found that baseline measures can be used to identify membership in high-risk trajectories of craving across treatment. We plan to examine whether baseline measures can be similarly used to identify membership in the identified stress trajectory-groups.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

People in treatment for opioid-use disorder differ in patterns of momentary stress.

Unique patterns of momentary stress are differentially associated with drug use and craving during treatment.

These differences may help explain why stress and lapse aren’t always associated.

Role of Funding Source:

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. The funding source had no role in the writing of this report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:Nothing Declared

Declarations of Interest: none

By lapse, we mean any instance of drug use in a person who had previously stopped and had intended to abstain; a lapse may or may not progress to a relapse, by which we mean continued use with negative consequences.

The final GMM had average posterior probabilities of membership in each group of ≥ 0.98. Therefore, we determined it was appropriate to use a classify-analyze approach to trajectory-group assignment.

References

- Ahmed SH, Walker JR, Koob GF, 2000. Persistent increase in the motivation to take heroin in rats with a history of drug escalation. Neuropsychopharmacology 22, 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Hull A, Epstein DH, 2021. Ambulatory assessment methods to examine momentary state-based predictors of opioid use behaviors. Current Addiction Reports, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Willner-Reid J, Vahabzadeh M, Mezghanni M, Lin JL, Preston KL, 2009. Real-time electronic diary reports of cue exposure and mood in the hours before cocaine and heroin craving and use. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66, 88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Tyburski M, Kowalczyk WJ, Burgess-Hull AJ, Phillips KA, Curtis BL, Preston KL, 2020. Prediction of stress and drug craving ninety minutes in the future with passively collected GPS data. Nature Digital Medicine 3, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari M, Epstein DH, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Kowalczyk WJ, Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Preston KL, 2015. Some of the people, some of the time: field evidence for associations and dissociations between stress and drug use. Psychopharmacology 232, 3529–3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Munoz RF, Reus VI, 1994. Cognitive-behavioral intervention increases abstinence rates for depressive-history smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol 62, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP, 1985. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis 173, 412–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M, Kazeminia M, Abdoli N, Khaledipaveh B, Shohaimi S, Salari N, Hosseinian-Far M, 2020. The effect of methadone on depression among addicts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 18, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Stull SW, Kowalczyk WJ, Phillips KA, Schroeder JR, Bertz JW, Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Mezghanni M, Nunes EV, Epstein DH, Preston KL, 2019. Stress, craving and mood as predictors of early dropout from opioid agonist therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend 202, 200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Stull SW, Bertz JW, Burgess-Hull AJ, Lanza ST, Curtis BL, Phillips KA, Epstein DH, Preston KL, 2021. Beyond abstinence and relapse II: momentary relationships between stress, craving, and lapse within clusters of patients with similar patterns of drug use. Psychopharmacology, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, 2019. Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1-143,

- Preston KL, Epstein DH, 2011. Stress in the daily lives of cocaine and heroin users: relationship to mood, craving, relapse triggers, and cocaine use. Psychopharmacology 218, 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Kowalczyk WJ, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Mezghanni M, Epstein DH, 2018. Before and after: craving, mood, and background stress in the hours surrounding drug use and stressful events in patients with opioid-use disorder. Psychopharmacology 235, 2713–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proust-Lima C, Philipps V, Liquet B, 2017. Estimation of extended mixed models using latent classes and latent processes: the R package lcmm. Journal of Statistical Software 78, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts NP, Roberts PA, Jones N, Bisson JI, 2016. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4, CD010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serre F, Fatseas M, Denis C, Swendsen J, Auriacombe M, 2018. Predictors of craving and substance use among patients with alcohol, tobacco, cannabis or opiate addictions: commonalities and specificities across substances. Addictive Behaviors 83, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Alvares K, Nespor SM, Grunberg NE, 1992. Effect of stress on oral morphine and fentanyl self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 41, 615–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, 1993. Immobilization stress-induced oral opioid self-administration and withdrawal in rats: role of conditioning factors and the effect of stress on “relapse” to opioid drugs. Psychopharmacology 111, 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Funk D, Erb S, Brown TJ, Walker CD, Stewart J, 1997. Corticotropin-releasing factor, but not corticosterone, is involved in stress-induced relapse to heroin-seeking in rats. J Neurosci 17, 2605–2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, 2004. Negative affect and smoking lapses: a prospective analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 72, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Glass GV, 1977. Meta-analysis of psychotherapy outcome studies. Am Psychol 32, 752–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SE, Bacon AK, Randall PK, Brady KT, See RE, 2011. An acute psychosocial stressor increases drinking in non-treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology 218, 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.