Sinonasal mucosal melanoma (SNMM) is a rare and aggressive malignancy with a reported 5-year survival rate ranging from 20%–39%.1,2 Treatment recommendations are predominantly based on small retrospective series and extrapolated data from cutaneous melanoma studies. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend surgical resection with adjuvant radiation for resectable tumors.3 The approach to surgical resection has evolved over time, driven by the advent of endoscopic techniques. Radiation and systemic therapy options, including immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI), have similarly evolved. Despite multimodality advances, overall survival (OS) rates for patients with SNMM remain poor.

We describe the management paradigm and survival outcomes for 100 consecutive patients with SNMM treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between January 1997 and December 2018. We compared treatments and outcomes for patients treated at different time points. Three distinct periods were identified; the first historical reference period (January 1997 – December 2006), the second following the introduction of endoscopic surgical techniques to our institution (January 2007 – July 2010), and the third following introduction of ICI (August 2010 – December 2018). This allowed us to compare survival outcomes between different management paradigms.

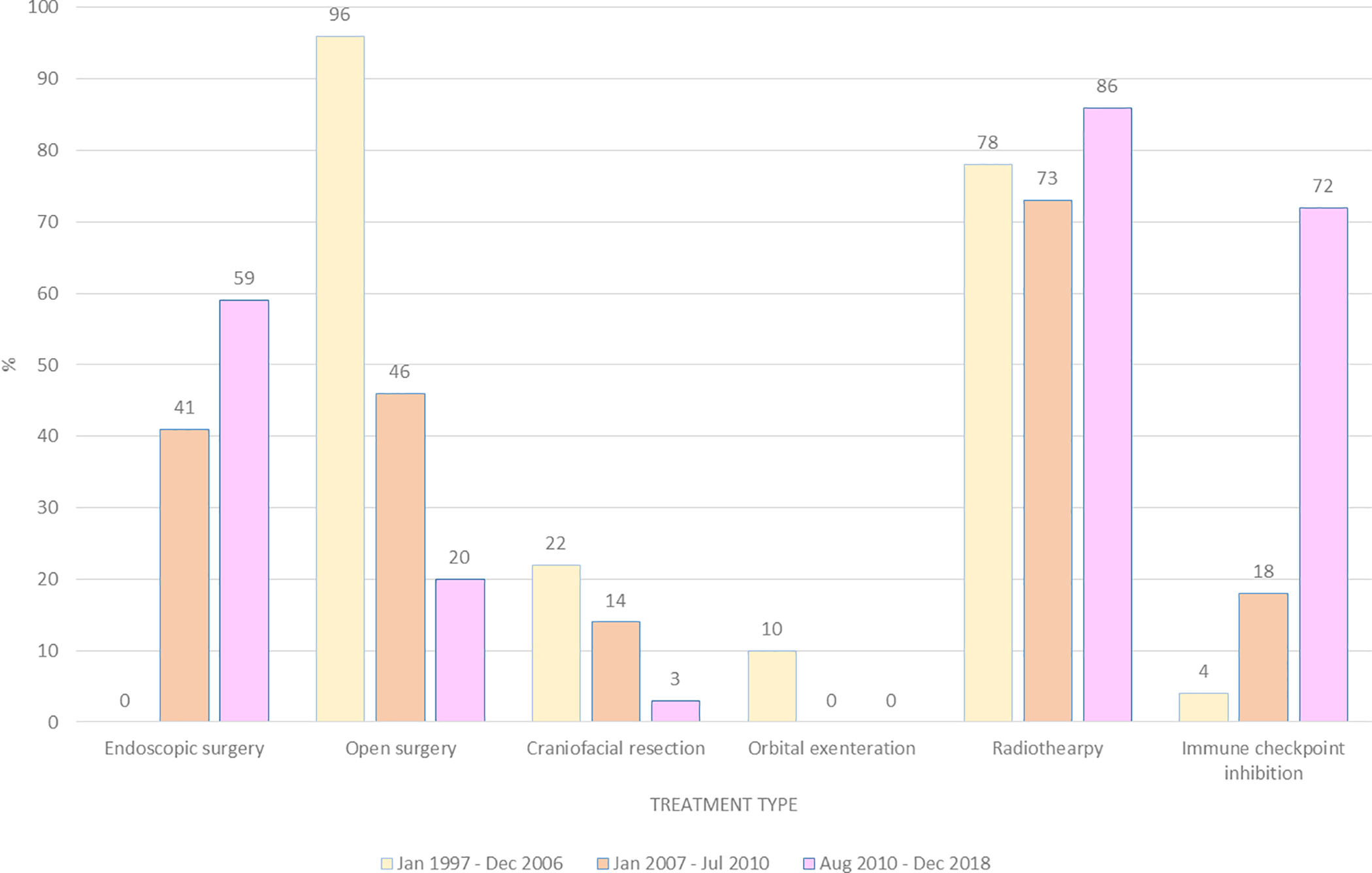

Surgical resection was performed in 87% of patients. Surgery was more common during the first time period compared to the second or third time periods (96% versus 86% versus 79%, respectively; p = 0.069), and evolved from exclusively open procedures to predominately endoscopic procedures. Orbital exenteration and craniofacial resection were almost entirely abandoned by the end of the first time period. Radiotherapy was administered to 79% of patients, and did not significantly differ between time periods. There was no difference in overall survival between patients treated with open versus endoscopic surgery (p=0.734), or between patients treated with or without radiotherapy (p=0.959).

ICI was used in 23 patients from the year 2011 onwards. Initially, ICI was administered for unresectable sinonasal disease and distant metastases. Later, ICI was incorporated in an adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting. Treatment toxicities were reported in 14 patients (61%) and necessitated pause or cessation of therapy in six (26%). of those patients. There were no deaths attributable to ICI. In those patients with clinically detectable disease at the commencement of ICI therapy (n=20), a partial or complete response was seen in 45% (n=9). Grouping patients based on the presence or absence of locally uncontrolled disease at the start of ICI revealed that those who had residual/recurrent local disease had an inferior median survival to those who achieved local control and were given ICI for distant metastases (6 months versus 24 months, respectively).

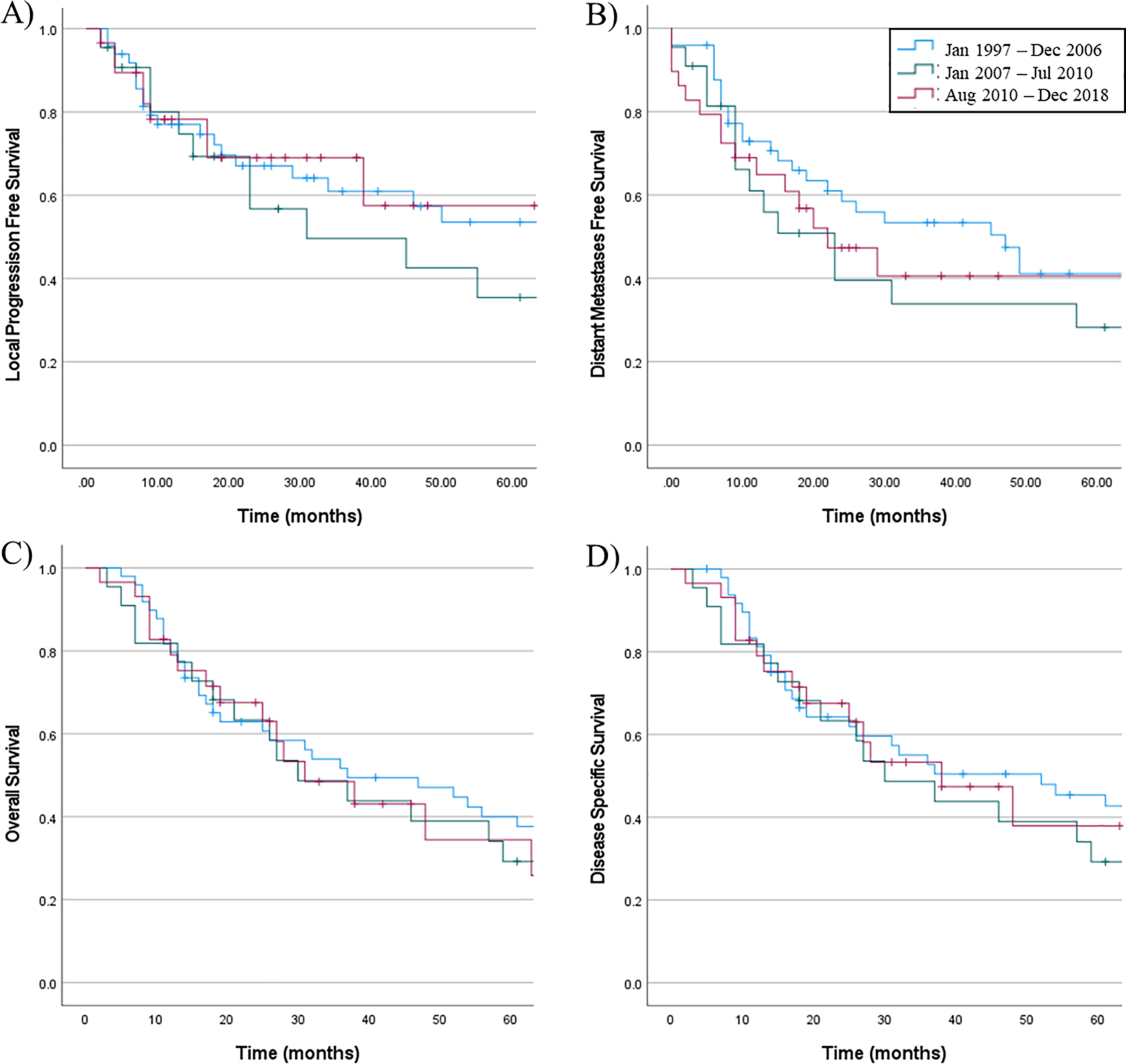

Overall survival (OS) of the entire cohort at 2 years was 67.5% and at 5 years was 38%, with a median survival estimate of 37 months (95% confidence interval, 21–53 months). Disease specific survival (DSS) at 2 years was 69.5% and at 5 years was 42.4%. Local progression free survival (LPFS) at 2 years was 58.2% and at 5 years was 39.4%. Distant metastases free survival (DMFS) at 2 years was 51.3% and at 5 years was 36.6%. There was no difference in OS or DSS between patients treated during the three time periods (p=0.800, p=0.727, respectively), despite major changes in the type and extent of surgical resection.

Our results confirm the poor prognosis associated with SNMM. Our institutional 5-year OS rate of 38% is comparable to the 20%–38% reported in the literature.2,4,5 The poor survival is partially driven by the propensity of SNMM toward distant metastases,6 although local recurrence rates remain uncomfortably high as well.7–9

Our institution has maintained interest in the management of SNMM over several decades10–12. As a result of this work, we have gradually moved away from radical surgery. The reasons for this are twofold: firstly, the high rate of distant metastases makes it difficult to justify highly morbid surgery. Secondly, the advent of endoscopic surgical techniques has enabled avoidance of the morbidity of transfacial approaches in most patients without compromising survival outcomes.13 The importance of achieving adequate resection remains paramount, regardless of surgical technique. 9,13–16 Consequently, we now avoid surgery in those patients with orbital or intracranial extension of disease.

The majority of the post-operative patients in our study received adjuvant radiotherapy, a decision based on evidence from several studies showing improved local control with the addition of radiation.2,8,17–19 None of these studies, however, demonstrated a survival benefit. In our cohort, the addition of radiation failed to significantly improve OS, DSS, or LPFS, although these results must be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size in the non-irradiated group. This is not entirely unexpected, due to the fact that much of the mortality occurs as a result of distant metastases. The goal of locoregional therapy, including both surgery and radiation, is to prevent the morbidity of progressive local disease.

We believe that ICI has a role in the adjuvant setting due to the propensity of SNMM to metastasize early and widely. We noted with interest that median survival was 24 months in patients who had locally controlled disease, compared with 6 months in patients who had unresectable primary or recurrent local disease. This finding reinforces the importance of achieving local control through surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy whenever possible. Another area of interest is the use of neoadjuvant ICI for patients with borderline resectable disease, in the hopes that it will permit less morbid surgical resection. Prospective trials examining the use of ICI in both the definitive and adjuvant settings in the management of SNMM are required.

Treatment of SNMM remains challenging given the overall rarity and poor prognosis of the disease. While surgery and adjuvant radiation are the mainstay of current treatment, our results show that avoidance of highly morbid surgery does not significantly impair survival outcomes. ICI offers an enticing addition to the current treatment paradigm, but there is the potential for significant toxicity, and clear evidence of benefit in treating SNMM is lacking. Future research efforts should focus on improving survival outcomes while preserving quality of life.

Figure 1.

Treatment type for patients actively treated for sinonasal mucosal melanoma, grouped by year of diagnosis.

Figure 2.

A) Local progression-free survival, B) distant metastasis–free survival, C) overall survival, and D) disease-specific survival for patients actively treated for sinonasal mucosal melanoma, grouped by year of diagnosis. None of the results are statistically significant.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gal TJ, Silver N, Huang B. Demographics and treatment trends in sinonasal mucosal melanoma. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(9):2026–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno MA, Roberts DB, Kupferman ME, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the nose and paranasal sinuses, a contemporary experience from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer. 2010;116(9):2215–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfister DG, Spencer S, Adelstein D, et al. Head and Neck Cancer Treatment Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2020;Version 1.2020.

- 4.Ascierto PA, Accorona R, Botti G, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;112:136–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amit M, Tam S, Abdelmeguid AS, et al. Patterns of Treatment Failure in Patients with Sinonasal Mucosal Melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(6):1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manolidis S, Donald PJ. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: review of the literature and report of 14 patients. Cancer. 1997;80(8):1373–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng YF, Lai CC, Ho CY, Shu CH, Lin CZ. Toward a better understanding of sinonasal mucosal melanoma: clinical review of 23 cases. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70(1):24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samstein RM, Carvajal RD, Postow MA, et al. Localized sinonasal mucosal melanoma: outcomes and associations with stage, radiotherapy, and positron emission tomography response. Head Neck. 2016;38(9):1310–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun CZ, Li QL, Hu ZD, Jiang YE, Song M, Yang AK. Treatment and prognosis in sinonasal mucosal melanoma: A retrospective analysis of 65 patients from a single cancer center. Head Neck. 2014;36(5):675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah JP, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1977;134(4):531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel SG, Prasad ML, Escrig M, et al. Primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2002;24(3):247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganly I, Patel SG, Singh B, et al. Craniofacial resection for malignant melanoma of the skull base: report of an international collaborative study. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2006;132(1):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sayed Z, Migliacci JC, Cracchiolo JR, et al. Association of Surgical Approach and Margin Status With Oncologic Outcomes Following Gross Total Resection for Sinonasal Melanoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(12):1220–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilain L, Houette A, Montalban A, Mom T, Saroul N. Mucosal melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014;131(6):365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lombardi D, Bottazzoli M, Turri-Zanoni M, et al. Sinonasal mucosal melanoma: A 12-year experience of 58 cases. Head Neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1:E1737–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penel N, Mallet Y, Mirabel X, Van JT, Lefebvre JL. Primary mucosal melanoma of head and neck: prognostic value of clear margins. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):993–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krengli M, Masini L, Kaanders JH, et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: analysis of 74 cases. A Rare Cancer Network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(3):751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temam S, Mamelle G, Marandas P, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2005;103(2):313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarev S, Gupta V, Hu K, Harrison LB, Bakst R. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(5):1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]