Abstract

Background:

Good breastfeeding technique is important in ensuring adequate milk delivery and preventing breastfeeding problems. Exclusive breastfeeding rate is quite low, and requisite skills regarding proper positioning and attachment of an infant while breastfeeding appears lacking among mothers in Nigeria. This study was undertaken to assess breastfeeding techniques of mothers attending the well-child clinics of two tertiary hospitals in southeast Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional descriptive study of 396 mother and child pairs who attend the well child clinics of two tertiary hospitals in Enugu (Enugu state University Teaching Hospital and University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital) between September 2018 and February 2019. An interviewer administered, well-structured pro forma was used to collect data while mothers were observed closely as they breastfed and scored using the World Health Organization criteria. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.

Results:

Most of the mothers studied (357; 90.2%) attended ante-natal care, and 365 (92.2%) of the deliveries were assisted by a health worker. Only 194 (49%) of mothers practiced good breastfeeding techniques. Maternal age (20–30 years) (P < 0.001, odds ratio [OR] 0.464), attendance to antenatal clinic (P < 0.001; OR 8.336), health education and demonstration on breastfeeding techniques before and after delivery (P = 0.001) and maternal level of education (χ2 = 13.173, P = 0.001) but not parity (P = 0.386; OR 1.192) were significantly associated with good breastfeeding techniques.

Conclusion:

There are suboptimal breastfeeding techniques among mothers. Increased awareness creation and regular demonstration of breastfeeding techniques are needed.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, child, Enugu, mother, technique, Allaitement, enfant, Enugu, mère, technique libre

Résumé

Contexte:

Une bonne technique d’allaitement est importante pour assurer une livraison adéquate du lait et prévenir les problèmes d’allaitement. Exclusive le taux d’allaitement est assez faible, et les compétences requises en ce qui concerne le positionnement et l’attachement appropriés d’un nourrisson pendant l’allaitement semblent manqué chez les mères au Nigéria. Cette étude a été entreprise pour évaluer les techniques d’allaitement des mères qui fréquentent les cliniques hôpitaux tertiaires dans le sud-est du Nigeria.

Matériaux et méthodes:

Cette étude descriptive transversale de 396 couples de mères et d’enfants assister aux cliniques pour enfants de deux hôpitaux tertiaires à Enugu (Hôpital universitaire d’Enseignement de l’Université d’Enugu et Université du Nigeria Enseignement hôpital) entre septembre 2018 et février 2019. Un intervieweur administré, bien structuré pro forma a été utilisé pour recueillir des données les mères ont été observées de près au fur et à mesure qu’elles allaitaient et scorelaient selon les critères de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé. Les données ont été analysées à l’aide du SPSS version 22.

Résultats:

La plupart des mères étudiées (357; 90,2 %) soins prénatals, et 365 (92,2 %) des livraisons ont été assistées par un travailleur de la santé. Seulement 194 (49%) des mères pratiquaient de bonnes techniques d’allaitement. Âge maternel (20–30 ans) (P 0,001, rapport de cotes [OR] 0.464), présence à la clinique prénatale (P 0,001; OU 8.336), éducation à la santé et démonstration sur les techniques d’allaitement avant et après (P = 0,001) et le niveau d’éducation maternel (2 = 13,173, P = 0,001) mais pas la parité (P = 0,386; OR 1.192) ont été significativement associés avec de bonnes techniques d’allaitement.

Conclusion:

Il existe des techniques d’allaitement sous-optimales chez les mères. Création accrue de sensibilisation et une démonstration régulière des techniques d’allaitement sont nécessaires.

INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding is an unrivaled way of providing ideal food for the healthy growth and the development of infants and is equally of immense benefit to the mother and the community at large.[1,2] According to the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children's Emergency Fund, exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) in the first 6 months of life and breastfeeding along with safe and nutritionally adequate complementary food thereafter up to 2 years of age and beyond play a pivotal role in child health.[3,4] It provides various health benefits to both mother and child, including protecting children against a number of acute and chronic disorders. In terms of mortality, infants who are not breastfed are 6–10 times more likely to die than infants who are breastfed.[5,6,7] In Nigeria, according to the National Demographic Health Survey 2018, the practice of EBF is poor, with a rate of only 29%. Hence, the need to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding in our communities has been widely recognized. Promoting proper breastfeeding practices can avert majority of infant deaths. Accordingly, it is suggested that early and EBF should be a major part of the essential newborn care while breastfeeding continues for up to 2 years of age or beyond.[8] A number of factors (maternal and infant) have been reported to be associated with breastfeeding techniques and these relationships provide knowledge that assists health care providers and policymakers in decision-making.[9,10,11,12,13,14] The Government of Nigeria is implementing the Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI) through the existing health-care delivery system. The IMCI strategy recommended a systematic assessment of breastfeeding and emphasized counseling of the mother on proper positioning and attachment of the infant to the breast.[15] The right information and requisite skills regarding proper breastfeeding positioning and attachment appear lacking among our mothers. Effective breastfeeding is a function of the proper positioning of mother and baby and attachment of the child to the mother's breast.[16] Essentially, the positioning of the baby's body is important for good attachment and successful breastfeeding. Furthermore, most breastfeeding difficulties can be avoided if good attachment and positioning are achieved at the first and early feeds.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] Findings from the assessment of breastfeeding techniques would be beneficial for designing intervention programs that bring about positive behavioral changes among mothers for infant health.

The well-child clinic is an area where lactating mothers and their infants meet with their health-care workers for routine immunization, growth monitoring, health education, etc., It offers a great opportunity to assess maternal knowledge and skill regarding breastfeeding. Despite the importance of the above, there is no documented study conducted in Enugu State, southeast Nigeria, on the assessment of breastfeeding techniques, correct positioning of mother and baby, baby's attachment to breast, and effective sucking. This study was, therefore, undertaken to assess for correct breastfeeding techniques as practiced by mothers attending the well-child clinics of two tertiary hospitals in Enugu State, southeast Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional hospital-based study.

Study area/site

The study was carried out in the well-child clinics of the Enugu State University Teaching Hospital (ESUTH)/Parklane and the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) both in Enugu State, southeast Nigeria. These two facilities offer primary, secondary and tertiary health-care services to persons of all social classes and are the referral centers for the population of Enugu State and its environs.

Study population

The study population comprised mother and child pairs who gave consent for the study and met the inclusion criteria. They were recruited consecutively from the well-child clinics of ESUTH and UNTH over 6 months (September 2018 to February 2019). These two well-child clinics hold twice a week from 8 am to 4 pm and attend to an average of 50 mother/child pairs per clinic day.

Inclusion criteria

Any mother whose child is still breastfeeding

Informed consent given by the mother for the study.

Exclusion criteria

Any mother whose child was breastfed within the previous hour as the child may still be full and not willing to suckle the breast

Any mother whose child is not breastfeeding for any reason, for example, maternal illness

Caregiver/mother did not give consent.

Selection and evaluation of the participants

A total of 396 mother/child pairs who attended the well-child clinics of ESUTH and UNTH and met the inclusion criteria were recruited consecutively over 6 months (September 2018 to February 2019). Two trained research assistants were used for data collection. A structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire was developed and used for the study. The questionnaire had two sections: the first section had questions on the socio-demographic data of mother/child pairs and details of delivery while the second section was a grading system adapted from the WHO B-R-E-A-S-T feed observation form[26] which was used to assess mother's breastfeeding positioning, attachment, and effective suckling techniques. To assess these, the mother was asked to breastfeed and was observed closely and scored by a trained research assistant for correct body position (baby), correct attachment, and effective suckling using the scoring and grading system. Each parameter gotten correctly was given a score of 1 while anyone that was incorrectly done was scored zero. The total maximum score obtained is 13, position-7, Attachment-4, effective sucking -2. In the three areas of assessment, scores of between 5 and 7 in position, 3–4 in attachment, and 2 in effective sucking represent good scores.

After scoring, the research assistant then demonstrated good breastfeeding techniques to the mothers and corrected those who had bad techniques.

Study tools

A semi-structured validated questionnaire adapted from the WHO B-R-E-A-S-T Feed Observation form was used for collecting the relevant information regarding the socio-demographic factors, assessment of mothers’ knowledge of breastfeeding/exclusive breastfeeding, and assessment of breastfeeding positioning and attachment. The questionnaires were filled as the mothers were observed breastfeeding their babies.

The following scoring and grading system was developed and adopted to grade positioning (mother and infant) infant's mouth attachment and effective suckling during breastfeeding based on the WHO criteria.[26] Each criterion was assigned 1 point.

The WHO recommended criteria for good positioning, attachment, and effective suckling during breastfeeding are as follows:-

Correctness of breastfeeding positioning

Mother relaxed and comfortable

Mother sit straight and well-supported back

Trunk facing forward and lap flat

Baby's neck straight or bent slightly back and body straight

Baby's body turned toward mother

Baby's body close to mother's body and facing breast

Baby's whole body supported.

Criteria for grading correct position

One criterion from mother's position, one from infant's position or both from mother's position. Grade-Poor score 0–2

At least one criterion from mother's position and two or three criteria from infant's position. Grade-average score 3–4

At least two criteria from mother's position and three or four criteria from infant's position. Grade-good score 5–7.

Correctness of attachment

Chin touching breast

Mouth wide and open

Lower lip turned outward

More areola seen toward the baby’’ mouth.

Criteria for grading correctness of attachment

Any one of the four criteria. Grade-poor score 1 (poor attachment)

Any two of the four criteria. Grade-average score 2 (average attachment)

Any three or all the four criteria. Grade-good score 3–4 (good attachment).

Correctness of effective suckling

Slow sucks

Deep sucks

Sometimes pausing.

Criteria for grading effective suckling

Any one of the three criteria. Grade-poor score 1 (ineffective suckling)

Any two or all the three criteria. Grade-good score 2 (effective suckling).

Overall good breastfeeding technique is said to be practiced by a mother who has good scores in all the three techniques (positioning attachment and suckling) assessed.

Statistical analysis

Information obtained using the questionnaire was subsequently transferred into the data editor of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software for Windows® version 19.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA, 2011) for analysis. Descriptive statistics such as mean ± (standard deviation) and median were obtained for continuous variables, whereas categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test of significance was applied to test for associations, and the level of significance was taken as P < 0.05. Results were presented in tables and graphs.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the ESUTH/Park lane, Enugu Nigeria, on the 13th of September 2018 with the protocol number ESUTHP/C-MAC/RA/034/Vol. 11/76. Written informed consent was obtained from caregivers of all participants. This work was done in keeping with the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

RESULTS

Babies’ characteristics

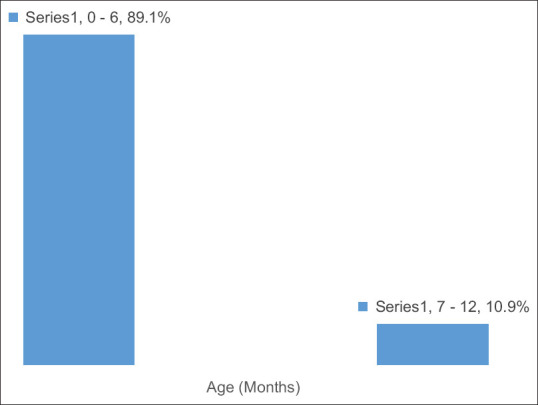

The mean age of the studied children was 7.01 ± 0.31 months. The majority were within the age range of 0–6 months (353; 89.1%), whereas the remaining were aged between 7 and 12 months (43; 10.9%) [Figure 1]. None of the children studied were more than 12 months of age. A greater percentage of the children studied (53.3%) were males with an M: F ratio of 1:1. Most (368; 92.9%) of the participants studied were of the Igbo tribe with Christianity as the dominant religion (386; 97.5%). The parents of the remaining 10 (2.5%) children were all Muslims.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of the children

A total of 357 (90.2%) of the mothers in the study attended ante-natal care, mainly at private health facilities (186; 52.1%). Three hundred and forty-five (345; 87.1%) of the mothers delivered in health facilities while the remaining 51 (12.9%) delivered at home. Three hundred and sixty-five (365; 92.2%) of the deliveries were assisted by a health worker while (370; 93.4%) babies were delivered at term. Seventy-six (76; 19%) of the deliveries were by cesarean Section and 30 (7.6%) of the babies had a birth weight <2.5kg.

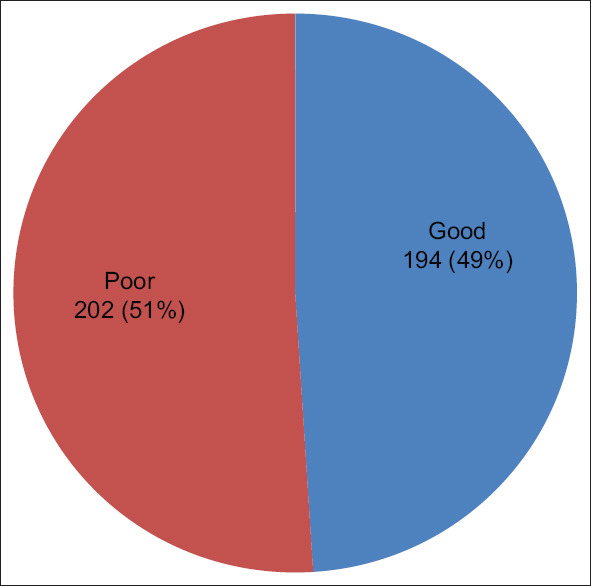

Maternal characteristics

Most of the mothers were aged 20 years and above, with only 20 (2.8%) being below 20 years. The mean age was 27.41 ± 2.55 years. Majority (372; 93.9%) were still married, with 324 (87.1%) living with their spouses as at the period the study was conducted. One hundred and seventy-seven (44.7%) of the mothers had only one child. A total of 313 (79%) mothers were employed while the remaining 83 (21%) were not employed [Table 1]. The mothers’ breastfeeding techniques scores are shown in Table 2. Only 194 (49%) of mothers practiced good breastfeeding techniques, having had good overall score in the three areas of assessment [Figure 2]. Maternal age (20–30 years) (P < 0.001, odds ratio [OR] = 0.464), attendance to Ante-Natal Clinics (P < 0.001; OR = 8.336), health education and demonstration on breastfeeding techniques before and after delivery (P = 0.001) and maternal level of education (χ2 = 13.17, P = 0.001) but not parity (P = 0.386; OR = 1.192) were significantly associated with good breastfeeding techniques [Table 3].

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <20 | 11 (2.8) |

| 20-30 | 210 (53.0) |

| >30 | 175 (44.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 372 (93.9) |

| Unmarried | 21 (5.3) |

| Parity/family size | |

| 1 | 177 (44.7) |

| 2-5 | 219 (55.3) |

| Level of education | |

| None | 4 (1.0) |

| Read and write | 25 (6.3) |

| Primary and above | 367 (92.7) |

| Presence of any breast disease/condition | |

| Present | 6 (1.5) |

| Absent | 390 (98.5) |

| Attended ANC | |

| Yes | 333 (84.1) |

| No | 31 (7.8) |

| TBA | 32 (8.1) |

| Mother given orientation about breast feeding techniques by a health worker | |

| Before | 239 (60.4) |

| After | 87 (22.0) |

| Both | 70 (17.7) |

ANC=Antenatal care

Table 2.

Assessment of breastfeeding technique of study participants

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Correct body position | |

| Mother relaxed and comfortable | 185 (46.7) |

| Mother sit straight and well-supported back | 340 (85.9) |

| Trunk facing forward and lap flat | 358 (90.4) |

| Baby neck straight or bent slightly back and body straight | 229 (57.8) |

| Baby’s body turned toward mother | 219 (55.3) |

| Baby’s body close to mother’s body and facing breast | 369 (93.2) |

| Baby’s whole body supported | 169 (42.7) |

| Criteria for grading for correct body position | |

| One criterion from mother’s position, one from infant’s position or both from mother’s position (poor) | 40 (10.1) |

| At least one criterion from mother’s position and two or three criteria from infant’s position (average) | 155 (39.1) |

| At least two criteria from mother’s position and three or four criteria from infant’s position (good) | 201 (50.8) |

| Correctness of attachment | |

| Chin touching breast | 326 (82.3) |

| Mouth wide and open | 371 (93.7) |

| Lower lip turned outward | 372 (93.9) |

| More areola seen toward the baby’s mouth | 355 (89.6) |

| Criteria for grading correctness of attachment | |

| Anyone of the four criteria (poor) | 8 (2.0) |

| Any two of the four criteria (average) | 53 (13.4) |

| Any three or all the four criteria (good) | 335 (84.6) |

| The correctness of effective suckling | |

| Slow sucks | 114 (28.8) |

| Deep sucks | 301 (76.0) |

| Sometimes pausing | 375 (94.7) |

| Criteria for grading effective suckling | |

| Anyone of the three criteria (poor) | 7 (1.8) |

| Any two or all the three criteria (good) | 389 (98.2) |

Figure 2.

Breast feeding techniques

Table 3.

Relationship between age, parity, level of education, antenatal care attendance, and orientation on breastfeeding techniques and breastfeeding technique

| Breast feeding technique | P | OR | 95% CI for OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Good | Poor | ||||

| Age group | |||||

| <20 | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 0.367 | 0.569 | 0.167-1.936 |

| 20-30 | 85 (40.5) | 125 (59.5) | <0.001 | 0.464 | 0.309-0.699 |

| >30 (ref) | 104 (59.4) | 71 (40.6) | |||

| Parity | |||||

| 1 | 91 (51.4) | 86 (48.6) | 0.386 | 1.192 | 0.802-1.772 |

| 2-5 | 103 (47.0) | 116 (53.0) | |||

| Education | |||||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | χ2=13.173*, P=0.001 | ||

| Read and write | 5 (20.0) | 20 (80.0) | |||

| Primary and above | 189 (51.5) | 178 (48.5) | |||

| ANC | |||||

| Yes | 184 (55.3) | 149 (44.7) | <0.001 | 8.336 | 2.853-24.351 |

| TBA | 6 (18.8) | 26 (81.3) | 0.528 | 1.558 | 0.394-6.161 |

| No (ref) | 4 (12.9) | 27 (87.1) | |||

| Orientation | |||||

| Before (ref) | 94 (39.3) | 145 (60.7) | |||

| After | 52 (59.8) | 35 (40.2) | 0.001 | 2.292 | 1.389-3.782 |

| Both | 48 (68.6) | 22 (31.4) | <0.001 | 3.366 | 1.389-5.936 |

*χ2. ANC=Antenatal care, OR=Odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval

DISCUSSION

This study assessed breastfeeding techniques as practiced by mothers in the well-child clinics of the two tertiary hospitals. Half of the mothers practiced good breastfeeding techniques, having had a good overall score in the three areas of assessment. This is similar to the findings of Kronborg and Vaeth in India where one-half of the mothers showed ineffective breastfeeding techniques.[27] However, in their study, more women had suboptimal positioning and more babies had poor attachment. These problems were significantly associated with mothers’ report of early breastfeeding difficulties. Cesarean section can negatively influence breastfeeding initiation and techniques due to mothers’ mobility limitations, positioning difficulties, post-surgical pain and discomfort, and separation of mother and infant in the first days after birth.[28,29] In addition, the analgesia administered to mothers for pain relief after cesarean section can affect infants’ ability to latch on their mothers’ breast.[30] It has been reported that mothers with cesarean section deliveries had more stressful breastfeeding than mothers who had vaginal deliveries.[31] Majority of the mothers in our study had vaginal delivery, and most babies delivered at term with a birth weight >2.5 kg. This may explain the better breastfeeding technique found in our study as poor sucking and attachment are associated more with preterm and low -birth weight babies.[9]

In this study, maternal age between 20 and 30 years was found to be significantly associated with good breastfeeding techniques. Younger mothers did not show this association. Similarly, younger mothers (<20-year-old) demonstrated poor positioning of their infants compared with other age groups.[9] Santo et al. from Brazil also reported that adolescent mothers had poorer breastfeeding technique.[32] This is probably because most of these young mothers are primipara without previous experience or practice of breastfeeding. This calls for intensification of activities to promote EBF for adolescent mothers with appropriate instruction for these mothers on correct breastfeeding techniques. However, in contrast, Lau et al. observed that maternal age had no significant impacts on breastfeeding techniques.[33]

Counseling nursing mothers for proper lactation before delivery with continued training thereafter are the main clinical pathways toward successful and sustained breastfeeding. This is one of the major aims achieved during antenatal visits. It is therefore not surprising in our study that attendance to ante-natal clinics had a significant association with good breastfeeding techniques. Similarly, Kishore et al. found that satisfactory breastfeeding knowledge was significantly higher in the mothers who received breastfeeding counseling.[34]

Mothers with more children were more likely to possess better breastfeeding techniques.[9] Multiparous women were also more likely to repeat their previous breastfeeding experiences and practices with their preceding children.[35] In contrast, first-time mothers who had little prior experience with infant feeding reported difficulties in handling their infants and in coordinating their movements during breastfeeding.[36] Furthermore, first-time mothers were less likely to have received trainings and demonstrations on breastfeeding techniques[37] and were more likely to use pacifiers, which have been shown to be negatively associated with breastfeeding techniques.[38] It is thus surprising in our study to find that parity was not significantly associated with good breastfeeding technique. Other factors, such as maternal level of education (that has a significant association with good breastfeeding technique) may be a possible reason. This is because an educated mother, even as a primipara, is more likely to understand information and instruction on good breastfeeding techniques. This was highlighted in a study by Tiruye et al. who noted that effective breastfeeding technique was 2.3 times more common among educated mothers compared to mothers with no formal education.[39] Majority (92.7%) of the mothers in our study had primary education and above.

More women had orientation about breastfeeding techniques by a health worker before delivery, while very few had it after delivery. This should be corrected as the practice of effective breastfeeding technique was significantly associated with mothers who had immediate breastfeeding technique counseling after birth and at least two postnatal visits.[39]

One limitation of this study is that it was carried out in tertiary health facilities of an urban setting where more women have access to good antenatal care, and their deliveries attended to by several cadres of health professionals, which exposed them to necessary health information including good breastfeeding practices. Hence, it may not be a good reflection of what is obtainable in the rural parts of a developing country like Nigeria, where such luxuries are lacking. Conduction of a similar study in rural settings will help to compare with the urban setting and also highlight what the situation in the country is, as the majority are rural dwellers.

CONCLUSION

Despite the importance of good breastfeeding techniques to the practice of successful breastfeeding of children, significant gaps still exist among mothers regarding information and requisite skills about breastfeeding. The creation of awareness by health-care workers need to be intensified with regard to impacting knowledge and skills on mothers toward improving their breastfeeding techniques.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salone LR, Vann WF, Jr, Dee DL. Breastfeeding: An overview of oral and general health benefits. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:143–51. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colen CG, Ramey DM. Is breast truly best? Estimating the effects of breastfeeding on long-term child health and wellbeing in the United States using sibling comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 2014;109:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization & UNICEF. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. 2002. [Last assessed on 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/FinalReportonDistribution.pdf .

- 4.UNICEF. Tracking progress on child and maternal malnutrition: A survival and development priority 2009. [Last assessed on 2020 Mar 15]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/tracking-progress-child-maternal-nutrition-survival .

- 5.UNICEF, Scientific Rationale: Benefits of Breastfeeding. 2012. [Last assessed on 2020 Mar 15]. http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Scientific_rationale_for_benefits_of_breasfteeding.pdf .

- 6.Horta BL, Victoria CG. Long-Term Effects of Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organisation. Protecting breastfeeding in Peru. 2013. [Last assessed on 2020 Mar 15]. Who.int/features/2013/peru.breastfeeding/en/

- 8.World Health Organization. Essential New Born Care. Report of Technical Working Group (Trieste, April 25-29, 1994) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyal RC, Banginwar AS, Ziyo F, Toweir AA. Breastfeeding practices: Positioning, attachment (latch-on) and effective suckling-A hospital-based study in Libya. J Family Community Med. 2011;18:74–9. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.83372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrand DA, McCarthy P, Tipton D, Merriman C, Schrank M, Newport M. Innovative use of influential prenatal counseling may improve breastfeeding initiation rates among WIC participants.J. Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46:458–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celik IH, Demirel G, Canpolat FE, Dilmen U. A common problem for neonatal intensive care units: Late preterm infants, a prospective study with term controls in a large perinatal center. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:459–62. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.735994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scrafford CG, Mullany LC, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Darmstadt GL, et al. Incidence of and risk factoes for neonatal jaundice among newborns in Southern Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:1317–28. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown A, Jordan S. Impact of birth complications on breastfeeding duration: An internet survey. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:828–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser DM, Cullen L. Postnatal management and breastfeeding. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2008;19:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO, UNICEF. Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (Training modules for Medical Officers) New Delhi, India: Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Rawool AP, Garg BS. Where and how breastfeeding promotion initiatives should focus its attention? A study from rural wardha. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:226–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinther T, Helsing E. Breastfeeding: How to Support Success: A Practical Guide for Health Workers. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 1997. pp. 10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inch S. Breastfeeding problems: Prevention and management. Community Pract. 2006;79:165–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blair A, Cadwell K, Turner-Maffei C, Brimdyr K. The relationship between positioning, the breastfeeding dynamic, the latching process and pain in breastfeeding mothers with sore nipples. Breastfeed Rev. 2003;11:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigert EM, Giugliani ER, França MC, Oliveira LD, Bonilha A, Espírito Santo LC, et al. The influence of breastfeeding technique on the frequencies of exclusive breastfeeding and nipple trauma in the first month of lactation. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2005;81:310–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coca KP, Gamba MA, de Sousa e Silva R, Abrão AC. Does breastfeeding position influence the onset of nipple trauma? Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2009;43:446–52. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342009000200026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huml S. Sore nipples. A new look at an old problem through the eyes of a dermatologist. Pract Midwife. 1999;2:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minchin MK. Positioning for breastfeeding. Birth. 1989;16:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1989.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadwell K. Latching-on and suckling of the healthy term neonate: Breastfeeding assessment. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:638–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narramore N. Supporting breastfeeding mothers on children's wards: An overview. Paediatr Nurs. 2007;19:18–21. doi: 10.7748/paed2007.02.19.1.18.c4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO/UNICEF. Breastfeeding Counseling Training Course Trainer's Guide, Part One, Sessions 5 Observing a Breastfeed. WHO/CDR/93.3, UNICEF/NUT/93.1: World Health Organization Geneva, CDD programme, UNICEF. 1993:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronborg H, Vaeth M. How are effective breastfeeding technique and pacifier use related to breastfeeding problems and breastfeeding duration? Birth. 2009;36:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tully KP, Ball HL. Maternal accounts of their breast-feeding intent and early challenges after caesarean childbirth. Midwifery. 2014;30:712–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CY, Ip WY. The efficacy of breastfeeding in Chinese women with different intrapartum experiences: A Hong Kong study. Hong Kong J Gynecol Obstet Midwifery. 2008;8:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cakmak H, Kuguoglu S. Comparison of the breastfeeding patterns of mothers who delivered their babies per vagina and via cesarean section: An observational study using the LATCH breastfeeding charting system. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:1128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlander AK, Edman G, Christensson K, Andolf E, Wiklund I. Contact between mother, child and partner and attitudes towards breastfeeding in relation to mode of delivery. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2010;1:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santo LC, de Oliveira LD, Giugliani ER. Factors associated with low incidence of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. Birth. 2007;34:212–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau Y, Htun TP, Lim PI, Ho-Lim S, Klainin-Yobas P. Maternal, infant characteristics, breastfeeding techniques, and initiation: Structural equation modeling approaches. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kishore MS, Kumar P, Aggarwal AK. Breastfeeding knowledge and practices amongst mothers in a rural population of North India: A community-based study. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55:183–8. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips G, Brett K, Mendola P. Previous breastfeeding practices and duration of exclusive breastfeeding in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1210–6. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0694-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauri PA, Zobbi VF, Zannini L. Exploring the mother's perception of latching difficulty in the first days after birth: An interview study in an Italian hospital. Midwifery. 2012;28:816–23. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang H, Li M, Yang D, Wen LM, Hunter C, He G, et al. Awareness, intention, and needs regarding breastfeeding: Finding from first-time mothers in Shanghai, China. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:526–34. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mauch CE, Scott JA, Magarey AM, Daniels LA. Predictors of and reasons for pacifier use in first-time mothers: An observational study. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiruye G, Mesfin F, Geda B, Shiferaw K. Breastfeeding technique and associated factors among breastfeeding mothers in Harar city, Eastern Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:5. doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0147-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]